Mining the Drawers

to Close the Loop.

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Marketing AUTHOR: Bilal Ahmad & Yi Pu

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

What drives Swedish Consumers to Recycle their Old

Cell phone?

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title:

Mining the Drawers to Close the Loop – What drives Swedish Consumers to

Recycle their Old Cell phones?

Authors:

Bilal Ahmad and Yi Pu

Tutor:

Darko Pantelic

Date:

2020-05-18

Key terms: Cell phone recycling in Sweden, determinants of recycling behaviour, theory of

planned behaviour, attitude towards recycling scheme, intention to participate in recycling

schemes,

Abstract

Background:

The cell phone industry causes numerous environmental problems due to its

extractive and unsustainable business practices. However, in recent years

there has been a shift within the industry towards more circular economy (CE)

centric business models. As a result, the industry has introduced a number of

recycling schemes which would not only mitigate unsustainable disposal

practices but also retrieve the precious material contained in old cell phones.

Thereby, reducing the dependence on virgin resource extraction and the

associated environmental degradation. Successful implementation however

hinges on the willingness of consumers to participate in these schemes.

Whereby a better understanding of consumers’ behavioural cues will help not

only the producers to increase the effectiveness of these schemes but would

from a policy making standpoint help facilitate this transition towards CE

centric business models.

Purpose:

The purpose of this study is to develop an explanation of the determinants

of recycling intention. Since, previous research indicates that intention to

perform a behaviour dictates the materialization of the desired behaviour.

Within this previous research, factors such as attitude, subjective norm,

perceived behavioural control, moral incentive, convenience, awareness of

consequences, concern for information security and environmental

assessment have been shown to predict a person’s recycling intention. In this

study, we empirically test the applicability of these factors in determining the

intention to participate in recycling schemes in the context of cell phone

recycling in a Swedish setting.

Method:

We adopted a positivist research philosophy, a deductive approach and an

explanatory research design to conduct this quantitative research. The

process started with a comprehensive literature to uncover the determinants

of recycling intention to develop 13 hypotheses. Following which we

surveyed 268 residents in Sweden to form generalizable insight about the

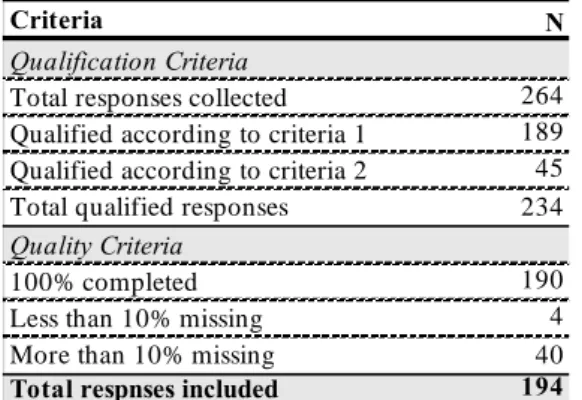

various factors identified in the literature. As a result, 194 surveys were

included based on the quality and qualification criteria. Finally, the data was

analysed utilising structural equation modelling to test the hypotheses.

Conclusion:

We were able to confirm 8 of the 13 hypothesis developed. The results

showed that moral incentive and convenience had the greatest influence on

intention to participate in schemes.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we express our deepest gratitude to Darko Pantelic, for not only providing

valuable feedback and lending us his academic expertise but also for making the process

intellectually stimulating. Without his continued guidance and patience we would not have been

able to complete this thesis.

Secondly, we would like to express our gratitude to our friends in the seminar group for going

beyond what was required in providing feedback, for challenging us intellectually and helping

us shape this research.

We would also like to thank all 264 of the wonderful people, that took out the time to complete

our survey. Without their contribution this study would not have been possible.

Finally, we thank our friends and family, whose support and encouragement made this journey

bearable.

Bilal Ahmad & Yi Pu

Jönköping, 18

thMay 2020

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1

Background ... 1

1.2

Problem Discussion ... 2

1.3

Previous Research ... 4

1.4

Purpose ... 5

1.5

Research Methodology ... 6

1.6

Delimitations ... 6

1.7

Thesaurus ... 7

2.

Literature review ... 8

2.1

Consumers as enablers of circular economy ... 8

2.1.1

Cell phone industry’s transition towards circular economy ... 8

2.1.2

Consumer Participation ... 9

2.1.2.1 Trade-in Schemes ... 11

2.1.2.2 Recycling Schemes ... 11

2.2

Determinants of consumers’ recycling behaviour... 13

2.2.1

Attitude, Subjective Norm and Perceived Behavioral Control ... 14

2.2.2

Moral Incentive ... 16

2.2.3

Convenience ... 17

2.2.4

Awareness of the problem ... 18

2.2.5

Concern for Information Security ... 19

2.2.6

Environmental Assessment... 20

3.

Methodology ... 23

3.1

Research Philosophy ... 23

3.2

Research Approach ... 24

3.3

Research Design ... 24

3.4

Research Method ... 25

3.5

Data Collection Method ... 26

3.5.1

Survey Design ... 26

3.5.1.1 Operationalization ... 27

3.5.1.2 Questionnaire Design ... 27

3.5.2

Sampling ... 29

3.6

Data Analysis Method ... 29

4.

Results and Analysis ... 33

4.1

Data, Demographics and Descriptive Statistics ... 33

4.2

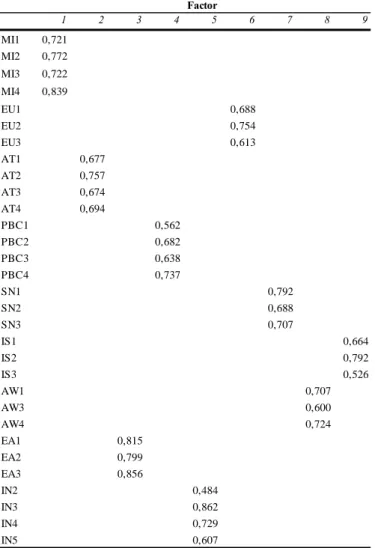

Exploratory Factor Analysis ... 36

4.3

Analysis of the Measurement Model ... 37

4.4

Analysis of the Structural Model ... 39

5.

Discussion ... 42

5.1

Moral Incentives ... 42

5.2

Subjective Norms and Awareness of the problem ... 43

5.3

Convenience ... 45

5.4

Attitude and Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) ... 46

5.5

Concern for information security ... 47

5.6

Environmental Assessment... 48

6.

Conclusion, Implications and Limitations ... 50

6.2

Implications for Policymakers... 52

6.3

Implications for producers ... 53

6.4

Limitations ... 54

7.

Reference list ... 56

Figures

Figure 1 - The proposed theoretical model ... 14

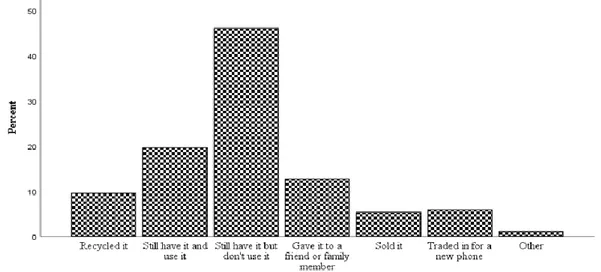

Figure 2 - What did you do with your old phone? ... 34

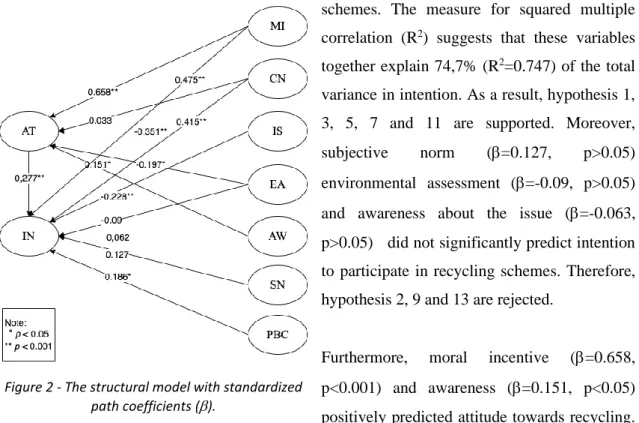

Figure 3 - The structural model with standardized path coefficients (). ... 39

Tables

Table 1 - Summary of the hypothetical assumptions ... 22

Table 2 – Operationalization process. ... 28

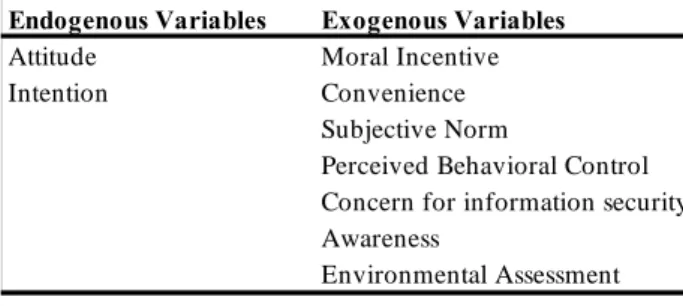

Table 3 - Classification of latent constructs ... 30

Table 4 - Criteria for assessing the Goodness-of-Fit ... 32

Table 5 - Data screeningprocess ... 33

Table 6 - Sample demographics ... 34

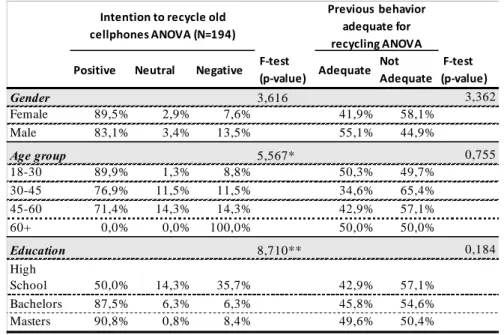

Table 7 - Frequency distribution and ANOVA results for recycling intention and past

behaviour ... 35

Table 8 - The rotated factor matrix ... 36

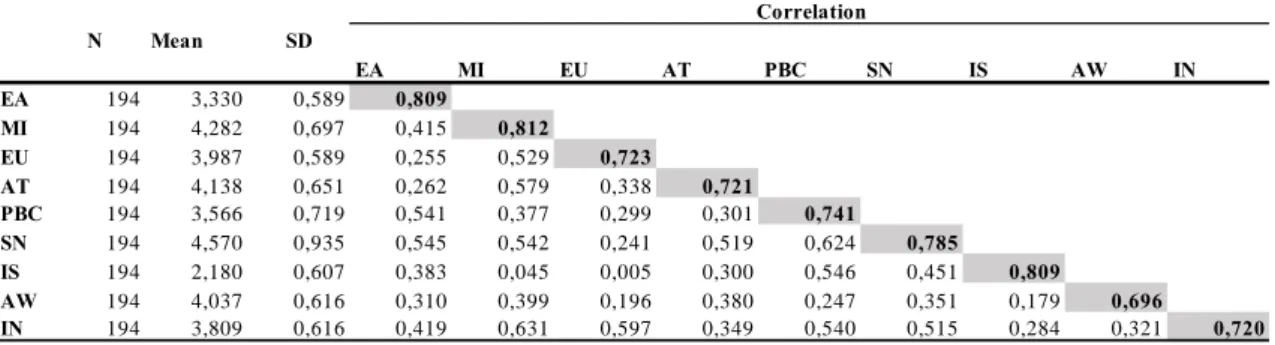

Table 9 - Evidence for Convergent Validity ... 37

Table 10 - Evidence for discriminant validity ... 38

Table 11 - Summary for the Measurement Model ... 38

Table 12 - Summary for the Structural Model. ... 39

Table 13 - Summary of the empirical findings ... 40

Appendix

Appendix Table 1 - Questionnarie ... 67

Appendix Table 2 - Cronbach’s alpha ... 74

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter starts with general introduction about how exponential growth and hyper consumption in the cell

phone industry is causing negative consequences for the environment. This is followed by a discussion on

Circular Economy and the need for increased consumer participation in producers recycling schemes. We then

proceed to provide an overview of the current state of research about recycling. A research gap is identified not

only with regards to the lack of a rich analysis about consumers’ cell phone recycling intention but also in

consideration to previous research on Swedish consumers. The subsequent section presents the research question

and articulates what it entails. The chapter end with a brief comment on the planned methodology,

identification of delimitations in order to frame the scope of this study.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) devices, such as cell phones, are for most people an important part of everyday life and influence the way we work, communicate, travel and much more (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018). Human population has doubled in the last 50 years and the consumption of electronic devices has grown six-fold during that time (Wann, 2011). In 2020, Including both smart and feature phones the number of phone users in the world reached 4.78 billion, which means 61.62% of all people owns a cell phone; the number for smartphone is 3.5 billion making 45.12% of the world’s population a smartphone owner (Turner, 2020).

Today’s technology enables reduction of human impact on nature, for instance by reducing traveling in favour of video conferencing or through smart buildings by optimizing energy usage (Chwieduk, 2003; Gharavi & Ghafurian, 2011; Yi & Thomas, 2007). However, the negative side of the ICT industry is the rapidly growing energy consumption due to manufacturing and powering our devices (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018). In Europe, ICT devices account for approximately 8-10% of the electricity consumption and 4% of the carbon emission (EU, 2018). Important to note is that those numbers do not include energy used for manufacturing the devices which is particularly alarming since they have a comparatively short life span (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018). Building a new smartphone, taking mining the rare materials into account, represents 85% to 95% of the device’s total CO2 emissions within two years, which means buying one new smartphone requires the same amount of energy as operating a phone for a decade (Wilson, 2018). Similarly, producing a mobile phone weighing 169 grams gives rise to 86 kg of waste material, in the form of for instance mining waste and slag products (IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute, 2015). Furthermore, in order to fulfil the ever growing demands for newer better

technology, the mining of rare earth metals have increased significantly and it is estimated that by 2080, the biggest metal reserves will no longer be underground (Ore Streams, 2020).

The fast development of mobile phones follows close to equally rapid replacement of outdated devices (Suckling & Lee, 2015). Over 60 per cent of mobile phone sales are replacements for already-existing phones, 90 per cent of which are still functioning when they are discarded (Mitchell, 2017). With an average life cycle of two years these new cell phone purchases can also be regarded more or less disposable (Wilson, 2018). This leads to the question what happens to the old phones? Consider the fact that the Green House Gas Emissions (GHGE) of smart phones increased 730% between 2010 to 2020 (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018) while the recycling rate of e-waste in Sweden decreased overall from 62.4% to 55.4% in a comparable period between 2008 and 2016 (Statista, 2020). These figures illustrate the notion that the discarded devices do not make it back to manufacturers or recycling facilities where at least some of the valuable materials could be extracted for reuse, refurbishing or recycling. Especially when considering that in some instances these discarded devices can yield significantly more rare metals in comparable weight than actual mineral ore (Nogrady, 2016).

1.2 Problem Discussion

In recent years Circular Economy (CE) has emerged as one of the most promising paradigms. The CE represents the most recent attempt to conceptualize the integration of economic activity and environmental wellbeing in a sustainable way (Murray, Skene, & Haynes, 2017). In a circular economy we keep resources in use for as long as possible, extract the maximum value from them whilst in use, then recover and regenerate products and materials at the end of each service life (The Waste and Resources Action Programme, 2018). However, a circular economy is not just a paradigm shift by reference to repairing, reusing, refurbishing, recycling and remanufacturing; it is also about the redesign of the future economy and society through new business models and new consumption behaviours (Tse, Esposito, & Soufani, 2015). In essence, ‘a circular economy is an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design’ (The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2012, p. 7). Here the word ‘intention’ is of particular importance, in that this intention is not only indicative of the manufacturers’ commitment to create production systems that are restorative or regenerative by design but also implies a certain degree of consumer responsibility to participate in the curation of these systems (Charter & Bakker, 2018; Hazen, Mollenkopf, & Wang, 2017; Rizos et al., 2016).

While we acknowledge that within the cell-phone industry current business models are driven by accelerated obsolescence and where the manufacturers might still be resistant towards extending

the use life of their smart phones (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018). Recent years have seen an increase in CE initiatives from major cell-phone manufacturers such as increased recyclability, use of recycled materials in production, greater repairability coupled with better take-back schemes and return facilities (Samsung Electronics, 2016, 2019; Watson et al., 2017). We argue that these initiatives suggest a paradigm shift towards a closed loop circular economy within the industry and is certainly reflective of the ‘intent’ towards greater producer responsibility.

In contrast, a plethora of research including that undertaken by academics and independent institution paints a rather bleak picture with regards to consumer involvement in facilitating the closed loop transition in the industry (see for example: Bai, Wang, & Zeng, 2018; Parker, 2019; Welfens, Nordmann, & Seibt, 2016; Welfens, Nordmann, Seibt, & Schmitt, 2013). Almost all of the previous research points to the fact that a large majority of consumers own more phones than they actually use and that a significant proportion of the old phones are stored at home (Bai et al., 2018; Parker, 2019; M. Welfens et al., 2013). In fact, according to a 2015 study conducted by Deloitte, regarding what people do with their old devices, 43% of the respondents indicated they store them as spares, 20% gave them to friends and family and only 19% sold or traded in their old phones (Statista, 2015). More interestingly, in a study undertaken by Bai et al., (2018) it was reported that a significant number of consumers because of information security concerns would instead of using proper channels to recycle, rather smash their phones into pieces before throwing it away.

These examples illustrate the point that for a CE transition to be successful within the cell phone industry, consumers have to play an active role in facilitating this transition (Ghisellini, Cialani, & Ulgiati, 2016; Kirchherr, Reike, & Hekkert, 2017; Yuan, Bi, & Moriguichi, 2006). More specifically, from a producer’s perspective one way to achieve this goal is through greater consumer participation in the recycling initiatives (Sarath, Bonda, Mohanty, & Nayak, 2015). Thereby ensuring continuous flow of materials within the industrial system which will significantly reduce the environmental cost of new productions (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018; The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2012). Hence, in order for the CE initiatives to be successful organizations have to pay attention to the behavioural cues of their consumers to implement strategies that foster greater consumer participation in the recycling schemes (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). More specifically, through uncovering the various factors that determine consumers’ intention to recycle, interventions can be designed to not only get consumers to form intentions to participate in recycling schemes but also to help consumers act on any existing intentions (M Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011).

1.3 Previous Research

Just as there exists a rich tradition of research on consumer behaviour and sustainability ((Fraj & Martinez, 2007; Harris, Roby, & Dibb, 2016; ölander & ThØgersen, 1995; Young, Hwang, McDonald, & Oates, 2009), an ever increasing body of research has also approached recycling from a consumer behaviour perspective (Hornik, Cherian, Madansky, & Narayana, 1995; Sarath et al., 2015). A substantial body of this research has been dedicated to understanding recycling intentions as the immediate antecedent of consumers’ recycling behaviour (Hornik et al., 1995). Furthermore, there appears to be general consensus among a great majority of these academics that people’s recycling intentions and consequent behaviour can ultimately be traced to the consumers’ attitudinal dispositions, normative influences and control considerations about the recycling behaviour (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017; Lizin, Van Dael, & Van Passel, 2017; Wang, Guo, Wang, Zhang, & Wang, 2018). However, given the diverse nature of recycling as a subject – not only in consideration to the object of recycling but also in regards to the contextual background in which recycling takes place (Botetzagias, Dima, & Malesios, 2015) – these factors are not always successful in predicting recycling intentions (Ramayah, Lee, & Lim, 2012; Tonglet, Phillips, & Read, 2004). As a consequence, many researchers have favoured inclusion of additional factors within their research to improve the prediction of intentions and behaviours (Botetzagias et al., 2015; Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017; F. Khan, Ahmed, & Najmi, 2019). Hence awareness about the issue (Wang, Guo, & Wang, 2016), personal moral norms (Botetzagias et al., 2015; Tonglet et al., 2004), economic incentives (Mak, Yu, Tsang, Hsu, & Poon, 2018) and convenience (Ng, 2019) associated with recycling have surfaced as important factors influencing recycling intention.

Observing the low recycling rate of cell phones, many researchers have put their attention into studying the consumer’s cell phone recycling behaviour (Sarath et al., 2015). Nonetheless, cell phone recycling is an emerging area of research within the recycling literature (Welfens et al., 2016). Therefore a large majority of research has primarily focussed on reporting the patterns and trends in consumer’s attitudes and behaviours towards recycling (Bai et al., 2018; Nnorom, Ohakwe, & Osibanjo, 2009; Welfens et al., 2013; Yin, Gao, & Xu, 2014). Here, in addition to the awareness (Yin et al., 2014), convenience (F. Khan et al., 2019) and incentives (Ongondo & Williams, 2011b; Welfens et al., 2016), concern for information security (Bai et al., 2018; Zhang, Wu, & Rasheed, 2020) has been highlighted as an important consideration in the context of cell phone recycling. Furthermore, for the studies that did involve an examination of consumer’s recycling intention (Nnorom et al., 2009; Welfens et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2020), the discussion and was constrained by the overarching purpose which has generally been geared towards

understanding recycling processes (Ongondo & Williams, 2011b), implications for policy making (Yin et al., 2014) effectiveness of awareness campaigns (Welfens et al., 2016) or individual’s perception of risks (Zhang et al., 2020). No previous research to the best of our knowledge has utilized the full spectrum of factors that have been highlighted in previous recycling literature to present a rich analysis about the determinant of intention to participate in cell phone recycling schemes. Especially in the context of CE from a producer’s perspective.

Finally, While there are a number of studies about recycling in Sweden (Hage, Söderholm, & Berglund, 2009), there exists no previous research that has approached cell phone recycling from a consumer behaviour perspective in Sweden. Previous research has shown that factors that are influential in affecting intention to recycle in one setting (for example developing countries) or for a specific recycling object (such as electronic-waste) may not necessarily be important in another situational context or a different recycling object (Botetzagias et al., 2015; Ramayah et al., 2012; Tonglet et al., 2004). Therefore, insights developed from previous research in Sweden about recycling behaviour in other contexts, for example household recycling (Hage et al., 2009), may not hold true for cell phone recycling in Sweden. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first that attempts to fill this research gap.

1.4 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to answer the following primary research question:

RQ: What factors determine Swedish consumers’ intention to participate in recycling schemes?

Previous research on recycling has shown a number of factors such as attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control, awareness of the problem, moral norms etc., to predict a person’s recycling intention (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017; Onel & Mukherjee, 2017; Wang et al., 2016; Welfens et al., 2013). In this study, we identify and empirically test the applicability of these factors in determining the intention to participate in recycling schemes in the context of cell phone recycling in a Swedish setting. According, Geller (2002) promoting behaviour change involves examining which factors cause those behaviours, and applying well-tuned interventions to change relevant behaviours. We believe that a satisfactory answer to our research question would provide proper explanations of influences moulding pro-recycling behaviours. Which in turn offers valuable insights to identify the key touchpoints that not only corporations but other concerned

parties such as governments, academics and grassroots initiatives can explore to design interventions that would increase participation in recycling schemes.

1.5 Research Methodology

Given the nature of the research question, the research warrants a positivist research philosophy, a deductive approach and a descriptive research design to conduct this quantitative research. Both secondary and primary data will be collected. Here the secondary data collection in form of a comprehensive literature review will help us identify the various factors previous research in recycling literature has identified as predictors of recycling intention; that might be applicable to our context. While the primary data collection in form of survey will help us gather data from a large sample. This will enable us to (1) deduce generalizable insight about the Swedish populations’ intentions to participate in recycling schemes, and (2) test the applicability of the various factors identified in previous literature through various statistical analysis.

1.6 Delimitations

First and foremost, the study is being conducted from a producer’s perspective i.e. where the ultimate benefactor of the recycling activities is the producer. Therefore, other CE facilitating consumer behaviour such as reuse, resell and repurpose fall outside our scope. Moreover, previous research has also included demographic cues and has shown it relevance in the e-waste recycling context in a developing country. We argue that since this research is being conducted Sweden, a country ranking highly on the human development index (Statista, 2019), factors like income, locality etc., would not display similar variances in regards to the determinants of behaviour. Other factors such as age, gender and education could thus be addressed using the various statistic reporting techniques. Finally, non-random convenience sampling is also a limitation which will directly influence the validity and generalizability of the insights developed as result of this research (Babin & Zikmund, 2016).

1.7 Thesaurus

Circular Economy: an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and

design (The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2012).

Consumer Participation: A consumer can participate in the producers CE initiatives by ensuring

that that materials keep flowing within the producer’s supply loops (Watson et al., 2017; Welfens et al., 2016).

Producers: including manufacturers (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018; Welfens, Nordmann, & Seibt,

2016) and service providers such as network operators and retailers that play a considerable role in end of life product recovery (D’Antone, Canning, Franklin-Johnson, & Spencer, 2017; Watson et al., 2017).

Recycling Schemes: End of life cell-phone return/recovery through voluntary donation routes

(D’Antone, Canning, Franklin-Johnson, & Spencer, 2017).

Trade-in Schemes: End of life cell-phone return/recovery through commercial route. That is, a

recycling scheme with an added economic incentive to recycle (D’Antone et al., 2017).

Moral incentive: Incentives that induce people to translate any felt obligation or ‘moral norm’

into recycling action (Hage, Söderholm, & Berglund, 2009).

Convenience: consumer’s expectations in consideration to the time space and ease of use of

recycling scheme (Bai et al., 2018; F. Khan et al., 2019; Wan, Shen, & Choi, 2017).

Attitude: an individual favourable or unfavourable perception of performing a certain behaviour

(Ajzen, 1991)

Perceived behavioural control: The extent to which a consumer feels that it’s possible, and

practically feasible, to recycle their cell phones (Zhang et al., 2020).

Subjective norm: an individual’s evaluation whether a certain behaviour is encouraged or not by

important people and groups (Ajzen, 1991).

Concern for information security: An individual’s subjective evaluation of the objective risk

of recycling with regards to information security (Pennings & Smidts, 2003; Zhang et al., 2020).

Environmental Assessment: consumer’s perception of the environmental performance of their

2. Literature review

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter introduces the current state of research on topics being discussed in this study. The first part

makes up the case as to why this study is framed in the context of circular economy. We discuss how financial

viability is incentivizing companies to introduce various incentives; the success of which depends on greater

customer participation. We then introduce the idea of recycling schemes, discuss the current state of research

and justify to the reader why it is important to approach the topic from a consumer behaviour perspective. Due

to the nature of our research question, the second part is concerned with research model and hypothesis

development. We begin by providing justification for why the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) was chosen

as a suitable starting point. 5 additional constructs are added to the TPB, including moral incentive,

convenience, concern for information security, awareness of the problem and environmental assessment. The

remainder of the section is focussed on introducing each of the latent construct to the reader and justifying why

it was included in the theoretical model. Finally, hypotheses are developed at the end of each discussion in light

of the previous research associated with each latent construct.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1

Consumers as enablers of circular economy

This section builds on the discussion on consumer’s role in enabling the cell phone industry’s transition towards circular economy, something that was touched briefly in the previous chapter. We start this discussion by presenting an overview of the concept of circular economy (CE), why it is important, and perhaps more interestingly the reasons that make this transition towards CE viable for the cell phone industry. The subsequent section then presents the existing literature advocating for greater consumer participation for the development of circular economies. Here, the focus in not only on why consumers should participate in circular economy initiatives but also on how they can participate. We then present participation in trade-in schemes and recycling schemes as two viable alternatives. Here we place more focus on recycling schemes and explain why it is necessary to approach this topic from a consumer behaviour perspective.

2.1.1 Cell phone industry’s transition towards circular economy

Circular Economy (CE) is a concept that has been gaining attention in recent years (Ghisellini et al., 2016). Its potential contribution to sustainable development is the main reason. The concept aims at preventing rapid resource depleting and reducing waste generation (Feng & Yan, 2007; Ghisellini et al., 2016; Hazen et al., 2017). Within the concept of sustainable development, CE is viewed as a more tangible part of the broader concept (Ghisellini et al., 2016; Kirchherr et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2017). One of the key features of CE is resource efficiency and

dematerialization of electronic economy (Lieder & Rashid, 2016). In early stage, CE research was conducted largely in the areas of industrial process and applications (Korhonen, Honkasalo, & Seppälä, 2018). The adherence to linear economy concept of “take-make-dispose” was found as one of the major barriers to CE (Hazen et al., 2017). Therefore, scholars have recently shifted their interest to closed-loop supply chain (CLSC) practices, which involve remanufacturing process. The efficient implementation of CLSC systems hinges on the efficient recovery of the end of life products (The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2012; Welfens et al., 2016).

The cell-phone industry has in the past been a target of criticism with regards to its negative environmental consequences, such as the depletion of rare natural resources and poor recovery of end-of-life products (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018; Ongondo, Williams, & Cherrett, 2011). In this market both manufacturers (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018; Welfens et al., 2016) and service providers such as network operators and retailers (hereafter, referred collectively as producers) play an important role in not only new cell-phone sales but also considerably, in end of life product recovery (D’Antone et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2017). Furthermore, as opposed to other waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE), return systems for cell-phones yield positive financial outcomes for the producers (D’Antone et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2017). Since not only the recovery and treatment costs are considerably smaller compared to other WEEE items, the revenue generated for example through the reselling of the refurbished cell-phones, offers financial viability to the CE model (D’Antone et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2017). Hence, incentivized by this financial viability and in response to negative consumer sentiments, the cell phone producers over the years have introduced a number of schemes with the aims of increasing end of life product return/recovery (Samsung Electronics, 2016, 2019; Watson et al., 2017). However, for these schemes to be successful, greater consumer participation is required (Gallaud & Laperche, 2016). Consequently, in order to achieve greater participation producers need to develop a better understanding the various factors that influence their consumers’ willingness to participate in these schemes (Borrello, Caracciolo, Lombardi, Pascucci, & Cembalo, 2017). We discuss the concept of consumer participation in the following section.

2.1.2 Consumer Participation

Previous research on the topic has advocated for greater consumers responsibility and participation for the promotion of sustainable products and services (Feng & Yan, 2007; Ghisellini et al., 2016). The earlier research generally approached consumer participation from a policy making perspective. For example, Feng & Yan (2007), not only deemed consumer participation as ‘indispensable to the development of a circular economy’ and advocated the use policy as an instrument to encourage the public to acquire attitudes and habits about consumption

that are conducive to CE (Feng & Yan, 2007, p. 108; Geng & Doberstein, 2008). Or consider Matete & Trois (2008), who while analysing a zero waste program in Durban, South Africa, provided evidence that the successful implementation depended on the participation rate of households.

In the recent years the focus has shifted towards the impact of consumer participation on CE at the firm, industry or supply chain level. These researchers argue that while promotion of responsibility is crucial for CE (Ghisellini et al., 2016), little is known about consumers’ willingness to participate in a CE (Borrello et al., 2017). Hence, excluding the consumer and adapting a supply side view involves the risks of developing business models that may be unviable due to a lack of consumer demand (Kirchherr et al., 2017). Therefore successful CE models involves rethinking consumption (Moreau, Sahakian, van Griethuysen, & Vuille, 2017) whereby, supply chains must not only consider the various production and distribution, but also consumption processes. Hence, making the consumer the most central enabler of CE (Gallaud & Laperche, 2016).

In the context of the cell-phone industry a consumer can participate in the producers CE initiatives by ensuring that that materials keep flowing within the producer’s supply loops (Watson et al., 2017; Welfens et al., 2016). Whereby some components can be reused while other material can be recycled (The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2012). Hence, reducing the producer’s dependency on exploitative and extractive practices and as a result minimize or eliminate some of the negative consequences associated with new cell-phone production (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018). Previous studies have pointed out that the consumers can participate in the creation of circular economies through reusing, repairing, refurbishing or repurposing material good within their consumption cycles (Kirchherr et al., 2017). However, in the context of the cell-phone industry from a producer’s perspective, greater consumer participation is required in the manufacturer’s return schemes for the survival of their closed-loop supply chain (CLSC) systems (Bai et al., 2018; Sarath et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2017).

These schemes can be broadly categorized into commercial routes and donation routes to end of life product return/recovery. The donation routes to return/recovery include cell-phone returns or recovery when a consumer voluntarily disposes a cell-phone using a producer owned return facility such as in-store collection boxes (D’Antone et al., 2017). In this case a moral incentive i.e. personal satisfaction of doing good, seems to be the driving factor (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). In contrast, commercial routes generally involve a monetary incentive, such as a cash vouchers or discounts on (future) purchases (D’Antone et al., 2017) but may also include

charitable donations on behalf of customers (Watson et al., 2017; Welfens et al., 2016). For the purpose of this study, end of life cell phone return/recovery through voluntary donation routes are termed as recycling schemes whereas those incentivized through commercial routes are termed as trade-in schemes.

Since this study is primarily focussed on recycling schemes a detailed discussion on trade-in schemes falls outside the scope. However, in order to inform the reader with the major differences between the two concepts, a brief discussion on trade-in scheme is presented in the next section.

2.1.2.1 Trade-in Schemes

As mentioned previously, trade-in schemes represent an overarching term which is indicative of the commercial route to cell phone return/recovery (D’Antone et al., 2017). And in the context of this study, trade-in schemes serve as an extension to the concept of recycling schemes by introducing an economic incentive to the construct. Here, an economic incentive is indicative of a system that relies on the immediate material compensation of users that motivates more people to recycle or return their old phones (Welfens et al., 2016, 2013). These incentives generally include discounts and vouchers but could also include charitable donations, such as Telenor’s take-back via sport clubs who receive money for each used cell phone collected (Ongondo & Williams, 2011a; Watson et al., 2017; Welfens et al., 2016). Similarly, trade-in schemes offering cash for returned mobile phones also have a noticeable impact on the collection levels. However, this incentive is generally reserved for newer models that can be resold by the producer (Watson et al., 2017; Welfens et al., 2016).

In contrast, a number of studies have provided evidence that the willingness to recycle is negatively influenced when the direction of these economic incentives is reversed (Ongondo & Williams, 2011b, 2011a; Yin et al., 2014). That is, when the consumer is required to pay for the recycling services or when the consumers perceive the producers to be deriving greater economic benefit (Bai et al., 2018; Ongondo & Williams, 2011a; Yin et al., 2014). However, as pointed out previously incentives of any kind – cash, discounts or charity – are generally influential on consumers’ willingness to return their old cell phones (Bai et al., 2018; Sarath et al., 2015; Welfens et al., 2016).

2.1.2.2 Recycling Schemes

By definition, recycling refers to the disposal of waste (unwanted materials) into a material cycle, in order to minimize environmental pollution (Geiger, Steg, van der Werff, & Ünal, 2019). In essence, sufficient recycling can recover valuable materials, and these materials can be put into

new products for reuse, which can reduce the consumption of raw materials, save energy, and help prevent air pollution and water pollution (Tanskanen, 2013). It is also worth mentioning that in the context of circular economies in the cell phone industry, although recycling mobile phones and other ICT products is perhaps not the most sustainable option, it is the best available solution – in addition to prolonging the use phase – for tackling the resource problem at present (Welfens et al., 2016). However, the small size of cell-phone devices makes it susceptible to being stored at home, forgotten in drawers, particularly when there is a lack of intention to recycle (Bai et al., 2018; Sarath et al., 2015). This storability of cell phone devices requires extra motivation on part of the consumer since not only proper consumer awareness is required for a recycling system to perform efficiently (Sarath et al., 2015), but also sufficient consumer participation is imperative for a successful mobile phone recycling system (Bai et al., 2018).

According to Sarath et al., (2015), previous research on cell phone recycling has generally focused on five distinct areas: Generation and Management of mobile phone waste, Consumer Behavioural studies, Economics of mobile phone recycling, Toxicity assessment and finally, Material Identification and Recovery. While material recovery is perhaps the largest area of interest for researchers, consumer behaviour is arguably the most crucial parameter to improve the recycling rate of waste mobile phones (Sarath et al., 2015). Since the future of cell phone recycling rests mainly at the hands of cell phone users (Kirchherr et al., 2017; Sarath et al., 2015).

In the recycling literature with regards to consumer behaviour, three constructs are widely used by researchers: consumer attitudes towards recycling, behavioural intentions, and actual recycling behaviour (Hornik, Cherian, Madansky, & Narayana, 1995). Where, successful large-scale adoption of recycling practices results as a function of these constructs (Bai et al., 2018; Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017; Welfens et al., 2016). Therefore, proper understanding of influences moulding pro-recycling behaviours offers valuable insights for policymaking and helps to identify the key touchpoints that government, corporations and grassroots initiatives can explore to address environmental pressures more effectively (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017).

In conclusion, CE presents a viable alternative to eliminate or at least mitigate some of the negative environmental consequences of the cell phone industry (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018). This idea is further reinforced by the fact that producers are now realizing that implementing recycling schemes presents opportunities that offer both financial gains and intangible benefits (such as pacifying dissatisfied consumers) (D’Antone et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2017). However, in order to capitalize on this opportunity, a better understanding of consumer’s willingness to participate in recycling scheme is required. In the next section, we discuss the determinants of consumer’s

recycling behaviour by first presenting a theoretical model and then developing an understanding of each of the influencing factors identified in the theoretical model.

2.2

Determinants of consumers’ recycling behaviour

To understand human behaviour it is important to understand their psychological process (F. Khan et al., 2019). In fact the premise of understanding the determinants of recycling behaviour implies a research building socio-psychological model which helps to understand socio-psychological influences, captured by latent variables, on people's recycling behaviour (Lizin et al., 2017). For this purpose, we propose using the theory of planned behaviour as a suitable baseline model. Especially since this theory is largely considered to be the dominant theory in most the studies recorded on determinants of recycling behaviour (Ramayah et al., 2012; Wan et al., 2017) and has been used extensively in the past to study recycling behaviour in various contexts (Wan et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018).

Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) is an extension of Theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Martin Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). According to TRA, behavioural intention determines a person’s performance of a specified behaviour, while the person’s attitude and subjective norm jointly determine the behavioural intention concerning the behaviour in question (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). TPB extends the TRA by introducing an additional construct, specifically perceived behavioural control (PBC) to account for situations where the control over a specific behaviour is not necessarily fully volitional (Ajzen, 1985). Much like TRA, a person’s behavioural intention provides explanation for their behaviour, while the behavioural intention itself is influenced by perceived behavioural control, attitude and subjective norms (M Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011).

Furthermore, according to Ajzen (1985), TPB is open to the inclusion of additional predictors if it can be shown that they capture a significant proportion of the variance in intention or behaviour after the theory’s current variables have been taken into account. This flexibility offered by the TPB has allowed previous research to develop additional novel constructs that are particularly useful in explaining determinants of recycling behaviour. For example, Tonglet, Phillips, & Read’s (2004) study on recycling intentions and behaviour found that TPB’s three components could not adequately explain recycling behaviour unless a construct for moral norms was also incorporated in the model. Similar studies for example by Echegaray and Hannstien (2017) incorporated the concepts of Awareness of the problem and environmental assessment to extend the conventional TPB model. Whereas Khan et al., (2019) argued in favour of including convenience as a separate factor, independent of perceived behavioural control.

For our purpose we extend the TPB model further by introducing awareness (Welfens et al., 2016), environmental assessment (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017), concern for information security (Bai et al., 2018, Zhang et al., 2020), convenience (F. Khan et al., 2019) and moral incentive (Botetzagias et al., 2015) as additional latent constructs. Figure 1 illustrates our proposed model for the determinants of recycling behaviour. In following section, we aim to explain each construct and use the previous research to guide the hypothesis development.

Figure 1 - The proposed theoretical model

2.2.1 Attitude, Subjective Norm and Perceived Behavioral Control

Attitude is defined as an individual favourable or unfavourable perception of performing a certain behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). In the context of predicting consumers’ intention to recycle their cell phones, attitude refers to the positive or negative evaluation of recycling their cell phones (Zhang et al., 2020). Researchers have found that attitude is positively related to individuals’ recycling behaviour. The findings of a number of studies showed that the attitude has a positive influence on recycling intention (Bai et al., 2018; Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). When individuals have a more positive attitude, they are more likely to perform a certain behaviour (Ajzen and Fishbein, 2005). More specifically in the study conducted by Zhang et al., (2020) attitude was shown to have the greatest influence on intention. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Favourable attitude towards recycling will positively influence the intention to participate in recycling schemes.

While attitudes are an effective predictor of intention (Zhang et al., 2020), some previous research has indicated the existence of an attitude-behaviour gap (Conner & Armitage, 1998), especially when the desired behaviour has some ethical consideration (Geiger et al., 2019; Kim & Rha, 2014). Which is in fact the basic premise of the TRA, i.e. behaviour is not only determined by attitude but also subjective norm (M Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011). Ajzen (1991) defines subjective norm as to whether a certain behaviour is encouraged or not by important people and groups. In this context the subjective norm refers to the social pressure consumers experience in relation to recycling their smartphones. According to Echegaray & Hansstein (2017) social norm is the most significant factor predicting electronic waste recycling intention. More interestingly, in a research conducted by Hage, Söderholm & Berglund (2009), studying 2800 Swedish Households, it was reported that the higher one perceived the degree of recycling by one’s neighbours to be, the greater the rise in recycling rate. In fact, when consumers perceive social pressure to perform a certain behaviour, they are more likely to do so (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2000). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Subjective norm will positively influence intention to participate in recycling schemes.

Conner & Armitage (1998) argue that the TRA restricts itself to volitional behaviours by suggesting that behaviour is solely in control of intention. Since behaviours requiring skills, resources, or opportunities not freely available are likely to be poorly predicted by the TRA (Conner & Armitage, 1998). Furthermore, the intention-behaviour relationships are moderated in such a way that when actual control is high rather low, the effect of intention on behaviour is stronger rather than weaker (Fishbein & Azjen, 2012). Since it is not possible to assess what constitutes actual control over behaviour, the TPB attempts to also predict nonvolitional behaviours by incorporating perceptions of control over performance of the behaviour as an additional predictor. Perceived Behaviour Control (PBC), according to Ajzen (1991) be explained as the extent of ease or difficulty consumers perceive to perform a certain behaviour. In the context of e-waste recycling it captures to which extent the consumers feel that it’s possible, and practically feasible, to recycle their cell phones (Zhang et al., 2020). In short, consumers are more likely to recycle when they have the resources or ability to do so (Axsen and Kurani, 2013). A number of studies have shown PBC to have a significantly positive influence over recycling

intention (Botetzagias et al., 2015; Lizin et al., 2017; Wan, Shen, & Yu, 2014). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: PBC will positively influence intention to participate in recycling schemes.

As mentioned previously, attitude, subject norm and perceived behavioural control as the three constructs of TPB have been shown as effective predictors of recycling intention within the previous literature (Dixit & Badgaiyan, 2016; Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). However previous research has also criticized TPB for only being able to explain a limited amount of variance in both behavioural intention and behaviour (Botetzagias et al., 2015; Ramayah et al., 2012; Tonglet et al., 2004). For example, while PBC was shown to be an influential factor in predicting intention for battery pack recycling in Belgium (Lizin et al., 2017), it was shown to be completely insignificant in predicting intention to recycle plastic waste in Pakistan (F. Khan et al., 2019). Therefore, given the diverse nature of recycling as a subject not only in consideration to the object of recycling but also in regard to the contextual background in which recycling takes place. A number of researchers have advocated for inclusion of additional factors to more adequately explain intentions and behaviour. (Botetzagias et al., 2015; Conner & Armitage, 1998; Ramayah et al., 2012). The following section is aimed at explaining the five additional constructs included in our extension to the TPB, starting with moral incentive.

2.2.2 Moral Incentive

With regards to an incentive affecting attitude, the concept of perceived usefulness may serve as an appropriate point of departure. Perceived usefulness is defined as ‘the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her performance’ (Davis, 1989, p. 320) and is indicative of the consumer perceptions of consumption outcomes or the use-performance relationship (Davis, 1989; Eriksson, Kerem, Bank, & 2008, n.d.). It is considered an important factor shaping consumers’ attitudes (Davis, 1989).

Here, perhaps at the lowest level are the moral incentives – for example: satisfaction of fulfilling a societal obligation – consumers receive as a result of voluntary donations to recycling scheme (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). While higher levels include charitable donations and more importantly the economic benefits consumer avail through their participation in the trade-in schemes (Welfens et al., 2013). More interestingly, previous research has shown that in the absence of incentives consumers might adopt rigid attitudes when participating in a recycling scheme is below desired levels of convenience (Bai et al., 2018). However, when offered desired

incentives, consumers’ attitudes displays greater flexibility in over-looking inconvenience (Bai et al., 2018).

Since the recycling of household waste is a behaviour likely to contain elements of personal morality and social responsibility (Tonglet et al., 2004), it was considered appropriate to include this dimension within the model. Especially when considering that in previous studies of recycling behaviours, inclusion of a moral factor has been found to be particularly effective in predicting intention (Bai et al., 2018; Hage et al., 2009). In this study we include this dimension as moral incentive. We argue that moral incentives are incentives that induce people to translate any felt obligation or ‘moral norm’ into recycling action (Hage, Söderholm, & Berglund, 2009). Here, these moral norms relates to the individual’s personal beliefs about the moral correctness or incorrectness of performing a specific behaviour (Tonglet et al., 2004). Furthermore Botetzagias, Dima & Malesios (2015), proved empirically that moral norms are an important and largely independent predictor of recycling and have influence on both attitude and intention (Botetzagias et al., 2015) Therefore, since previous research has shown this moral dimension to be influential on both attitude (Bai et al., 2018; Vicente & Reis, 2008) and intention (Wan et al., 2017). We argue that incentivizing the fulfilment of these moral norms will have similar effects. Hence, we propose:

H4: Moral incentive will positively influence consumer’s attitude towards participation in recycling schemes.

H5: Moral incentive will positively influence consumer’s intention to participate in recycling schemes.

2.2.3 Convenience

Convenience is considered as the time, space and the perceived ease of an individual in managing waste (Wan, Cheung, & Shen, 2012). In context of the cell-phone industry convenience of use of a return scheme was shown to be one of the most important factors influencing both consumers attitudes (Bai et al., 2018; Welfens et al., 2016) and intention (F. Khan et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2017) towards recycling. It also worth mentioning that some of the previous research has also attributed convenience as internal characteristic of perceived behavioural control and have represented it as such in their research (Wang et al., 2018). Khan et al., (2019) argue that convenience in the context of recycling presents a completely different conceptualization, whereby PBC is representative of an intrinsic construct while convenience is extrinsic by nature.

An important concept is the idea of ease of use i.e. ‘the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort’ where by ‘an application perceived to be easier than other is more likely to be accepted by users’ (Davis, 1989, p. 320). Ease of use plays an important role in shaping consumer attitudes (Ajzen, 1991) since at times, seemingly useful systems are rejected by consumers due to the perceived difficulty of use (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). In fact, as a consequence of the rapid development of e-commerce, consumers are demanding door-to-door service solutions (Bai et al., 2018) and are generally aversive towards solutions that are time consuming (Van Beukering & Van Den Bergh, 2006) or perhaps inconvenient in term of accessibility (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). In the context our study we assume the factor convenience to be an extrinsic measure of consumer’s expectations in consideration to the time, space and ease of use of a recycling scheme (Bai et al., 2018; F. Khan et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2017) whereas PBC is an intrinsic measure of personal control and ability over the performance of behaviour itself (F. Khan et al., 2019). In addition to the influence of convenience on attitude, many previous studies on recycling behaviour have also shown convenience to be significantly related to recycling intention (F. Khan et al., 2019). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6: Consumer’s perception of convenience associated with recycling will positively influence consumer’s attitude towards participate in recycling schemes.

H7: Consumer’s perception of convenience associated with recycling will positively influence consumer’s intention to participate in recycling schemes.

2.2.4 Awareness of the problem

The topic of awareness in the context of cell-phone recycling and consumer behaviour has been one of the most frequently discussed factors (Hornik et al., 1995; Sarath et al., 2015). However, the idea of what incorporates awareness seems to have evolved slightly. While the earlier research classified awareness as consumers’ understanding of the risk associated with improper waste disposal and knowledge about recycling channels (Hornik et al., 1995). More recent research on the topic has also included awareness about resource (over)consumption into the construct (Bai et al., 2018; Welfens et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2014).

Previous research has suggested that, mobile phone recycling is very low in both developing countries and developed countries owing to the awareness level of the public (Sarath et al., 2015). In fact, in one of the earliest meta-studies on recycling behaviour conducted by Hornik et al., (1995, p. 109), it was suggested that “awareness of the importance of recycling and knowledge about recycling programs” was the determining factor between those who recycled and those who

didn’t. Subsequent studies on the topic have validated this proposition. For example, Nnorom, Ohakwe, & Osibanjo (2009) studied the response of Nigerian population toward mobile phone recycling and concluded that since the population is aware of the environmental deterioration taking place as result of waste generated by increased mobile production, they are very willing to take part in recycling programs. In contrast, Bai et al., (2018) argued that while customer awareness with regards to the existence of recycling channels has improved significantly in China, awareness level of pollution risk from improper disposal of waste mobile phones and its value in resource conservation need to be improved considerably.

In summary, awareness of environmental issues and concern for the state of the environment predicts a favourable disposition towards specific pro-eco-friendly standings and behaviours (Kim and Choi, 2005, Vicente-Molina et al., 2013). Previous research has shown awareness of the consequences to have influence on both attitudes towards recycling (Ramayah et al., 2012) and intention to recycle (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). Which leads to our hypothesis:

H8: Awareness of the problem will positively influence attitude towards recycling schemes. H9: Awareness of the problem will positively influence intention to participate in recycling schemes.

2.2.5 Concern for Information Security

Smartphones is for most consumers an important tool of everyday life, enabling several activities and services (Zhang et al., 2020). The versatility and personalization that comes with a smartphone is beneficial to the user in many ways but creates problems in terms of recycling, mainly since the phone contains plenty of personal and private information (Bai et al., 2018). According to Bai et al., (2018) 63.7% of consumers did not want to recycle due to low trust for recycling parties and fear of leakage of personal information. Unlike traditional mobile phones most parts of the smartphones are integrated and cannot be removed by the consumer without difficulties, which means the entire device needs to be sent to be recycled (Zhang et al., 2020). Even if the personal information has been deleted there has been cases of information being recovered illegally adding to security becoming a priority of consumers looking to recycle (Zhang et al., 2020). Thereby increasing consumers' perception of risk associated with cell phone recycling.

Risk perception can in this context be perceived as the subjective evaluation of the objective risk of recycling, especially information security (Pennings & Smidts, 2003; Zhang et al., 2020). Zhang et al. (2020) found that risk perception moderated the relationships between

conscientiousness and the TPB variables in such a way that these relationships will be weak for individuals high in risk perception. Furthermore, previous research outside the recycling domain has shown the perceived security risk associated with a systems to be a dominant factor in determining intention to adapt a new system(Lee, 2009; Rezaie, Abadi, Ranjbarian, & Zade, 2012). For example, Lee (2009) showed empirically this risk factor to exert a stronger effect on customers’ decision-making than the benefit factors, when they consider using online banking. Therefore, as risk perception with regards to information security plays an important role in predicting both attitude (Bai et al., 2018) and intention (Lee, 2009), we propose the following:

H10: Concern for information security will negatively influence attitude towards recycling old cell phones.

H11: Concern for information security will negatively influence intention to recycle cell phones.

2.2.6 Environmental Assessment

Environmental assessment is representative of consumer’s perception of the environmental performance of their country (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). This is a novel construct introduced in the recycling literature by Echegaray & Hannsstein (2017) arguing that people’s assessment of the environmental situation of one’s country is a factor predicting recycling behaviour.

Echegaray & Hannsstein (2017, p. 185) in the context of e-waste in Brazil, proved empirically that as evaluations about the state of the ecology go grimmer, the more motivated individuals are to embrace responsible waste disposal practices, which is reflected by their increased intentions to recycle.

We argue that as compared to Brazil, Sweden has a long tradition of environmental democracy (OECD, 2014). In fact as compared to the European average, residents of Sweden place a higher value on the environment by assigning greater importance to environmental protection (OECD, 2014). They also appear to be more satisfied with their country’s environmental quality than people in other European countries (OECD, 2014). Based on these insights, we argue that not only will people report higher level of satisfaction with the current state of environmental performance but that this positive assessment would in fact serve as a reinforcing factor on both attitude and intentions to participate in recycling. This concept is not so different than the idea of perceived policy effectiveness, which implies that people’s perception of an effective policy measure will increase the attractiveness of a pro-environmental behaviour (Wan & Shen, 2013). As a result people would form a positive attitude towards that behaviour and subsequently, when

a policy is perceived to be effective it will induces a higher level of intention to perform that behaviour (Wan & Shen, 2013). Hence, we propose the following

H12: Positive environmental assessment positively influences attitude towards participation in recycling schemes.

H13: Positive environmental assessment positively influences intention to participate in recycling schemes

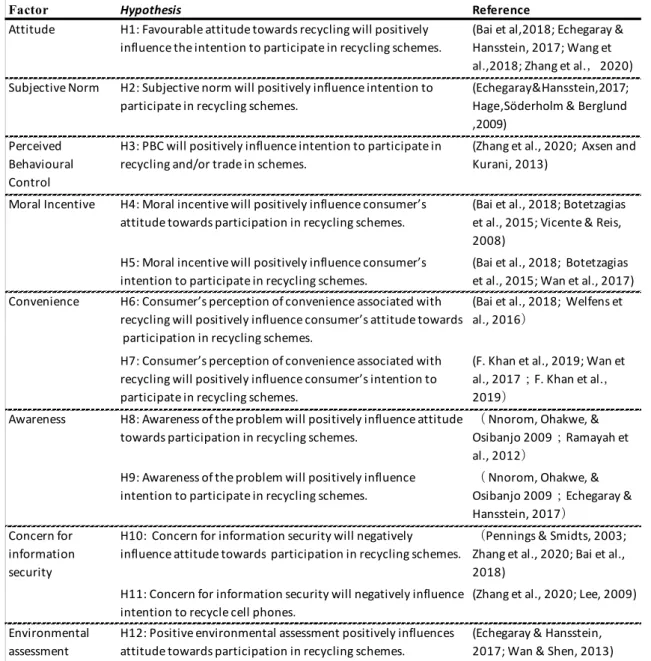

To sum up, in the beginning of the chapter we provided the arguments for why customer participation is imperative for the success of producers CE initiatives. We argued in favour of approaching the topic of recycling from a consumer behaviour perspective in order to develop understanding of the various factors moulding consumer pro-environmental behaviours. The second part of the chapter was aimed at utilizing the previous research to develop an understanding of the determinants of recycling intention. Which is the premise of our initial research question. Here, we followed the recommendations in the recycling literature to not only use TPB as a theoretical framework but also to extend the TBP by utilising the various factors that previous research has shown to be influential determinants of recycling intention. Furthermore, since there is evidence from the previous research that the applicability of these factors varies with the recycling object and the context, 13 hypotheses were developed to test if these factors would in fact predict intention to participate in recycling schemes in a Swedish setting. The table 1 presents a summary of the hypothesis developed. In the next chapter we discuss the methodological framework adopted in service of finding a satisfactory answer to our research question.

Table 1 - Summary of the hypothetical assumptions

Factor Hypothesis Reference

Attitude H1: Favourable attitude towards recycling will positively influence the intention to participate in recycling schemes.

(Bai et al,2018; Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017; Wang et al.,2018; Zhang et al.,2020) Subjective Norm H2: Subjective norm will positively influence intention to

participate in recycling schemes.

(Echegaray&Hansstein,2017; Hage,Söderholm & Berglund ,2009)

Perceived Behavioural Control

H3: PBC will positively influence intention to participate in recycling and/or trade in schemes.

(Zhang et al., 2020; Axsen and Kurani, 2013)

H4: Moral incentive will positively influence consumer’s attitude towards participation in recycling schemes.

(Bai et al., 2018; Botetzagias et al., 2015; Vicente & Reis, 2008)

H5: Moral incentive will positively influence consumer’s intention to participate in recycling schemes.

(Bai et al., 2018; Botetzagias et al., 2015; Wan et al., 2017) H6: Consumer’s perception of convenience associated with

recycling will positively influence consumer’s attitude towards participation in recycling schemes.

(Bai et al., 2018; Welfens et al., 2016)

H7: Consumer’s perception of convenience associated with recycling will positively influence consumer’s intention to participate in recycling schemes.

(F. Khan et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2017;F. Khan et al., 2019)

H8: Awareness of the problem will positively influence attitude towards participation in recycling schemes.

( Nnorom, Ohakwe, & Osibanjo 2009;Ramayah et al., 2012)

H9: Awareness of the problem will positively influence intention to participate in recycling schemes.

( Nnorom, Ohakwe, & Osibanjo 2009;Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017)

H10: Concern for information security will negatively

influence attitude towards participation in recycling schemes.

(Pennings & Smidts, 2003; Zhang et al., 2020; Bai et al., 2018)

H11: Concern for information security will negatively influence intention to recycle cell phones.

(Zhang et al., 2020; Lee, 2009)

H12: Positive environmental assessment positively influences attitude towards participation in recycling schemes.

(Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017; Wan & Shen, 2013) H13: Positive environmental assessment positively influences

intention to participate in recycling schemes

(Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017; Wan & Shen, 2013) Moral Incentive Convenience Awareness Concern for information security Environmental assessment