Values over value?

Pension Beneficiaries’ willingness to pay for socially responsible investments

and their perception of exponential growth.

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration, Finance NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAM OF STUDY: Civilekonomprogrammet AUTHORS: Emilia Jemtå & Matilda Kvist Björklund JÖNKÖPING: MAY 2021

Master thesis within Business Administration, Finance

Title: Values over value?

Authors: Jemtå, Emilia & Kvist Björklund, Matilda

Tutor: Duras, Toni & Hansen, Fredrik

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Willingness to pay for Socially responsible investments, Exponential growth bias,

socio-demographics, Psychological determinants, Psychographics.

Abstract

Background: As more individuals continuously become more conscious of the external influences of their decisions, integrating social and ethical criteria and perceived non-monetary value in their investment decisions, the interest in socially responsible investments (SRI) has escalated in the past decade. Reflecting this shift, the Swedish Pension Agency continuously increases the requirements and sustainability demands for the funds available in the premium pension selection. To investigate the underlying variables affecting the decision to invest socially responsibly, the authors of this thesis studied Swedish pension beneficiaries’ demographics, attitudes and beliefs.

Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to examine the socio-demographic and psychological determinants of pension beneficiaries' and the influence of these variables on the willingness to pay for socially responsible investments. The study will additionally explore the tendency to underestimate exponential growth in one’s pension savings.

Method: The study is conducted by collecting primary data in the form of quantitative research through an online questionnaire. Based on previous research, six hypotheses are developed. This in order to investigate the relationship between willingness to pay for socially responsible investments and several socio-demographic and psychographic variables. Additionally, to examine Swedish pension beneficiaries’ tendency to underestimate exponential growth. The data collected is analysed through a multiple linear regression model and other descriptive statistics to examine if the hypotheses are rejected or not.

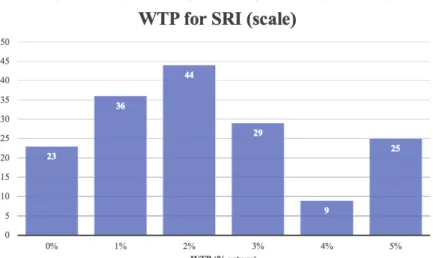

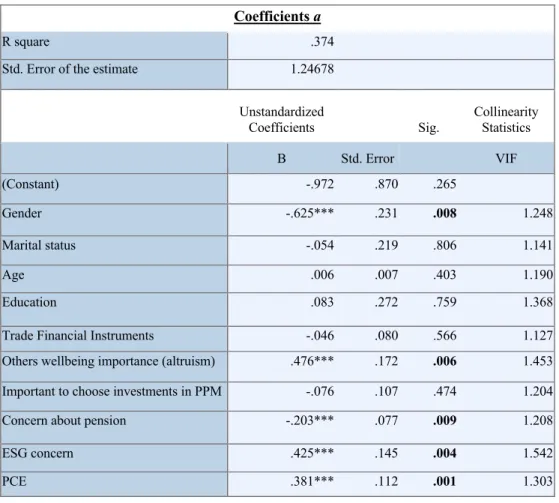

Conclusion: The majority of the subjects in the study are willing to pay for SRI. Gender significantly impacts the willingness to pay for SRI, as men demonstrate a lower willingness to pay than women. Furthermore, altruistic values, concern for one’s pension savings, concern for ESG-related issues (environmental, social and governance) and perceived consumer effectiveness proves to have a significant impact on the willingness to pay for SRI. Further, the sample demonstrated a definite tendency to underestimate exponential growth.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, we would like to express our sincerest gratitude towards our tutor Fredrik Hansen for all the support and knowledge provided throughout the process of writing this thesis. We would also like to declare our appreciation to Toni Duras for the aid in the statistical field and for always providing insightful answers to sometimes simple questions.

Secondly, we would like to thank everyone participating in this study by answering the survey, without you there would not exist any data to analyse.

Thirdly, we would like to acknowledge our fellow thesis writers and friends on the fourth floor, for all the encouragement, discussions, and long Friday afternoon fika-breaks. You unquestionably contributed to making this time more enjoyable.

Lastly, we would like to thank each other for the continual support, endless discussions and perseverance.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 11.2 Problem ... 4

1.3 Purpose ... 5

1.4 Delimitations ... 5

2. Literature Review ... 6

2.1 Socio-demographic variables ... 62.2 Psychological Determinants ... 7

2.3 Willingness to pay for SRI ... 12

2.4 Exponential growth bias ... 16

2.5 Hypotheses ... 18

3. Methodology ... 20

3.1 Approach ... 20

3.2 Data collection ... 21

3.2.1 Survey ... 21

3.2.2 Population and selection ... 23

3.3 Empirical method ... 23

3.3.1 Cronbach’s Alpha ... 23

3.3.2 Linear Regression Model ... 24

3.3.3 Variables ... 25

3.3.4 Dependent variables ... 25

3.3.5 Independent variables ... 26

3.4 Data analysis ... 29

3.5 Strengths and Limitations ... 30

4. Results ... 33

4.1 Descriptive statistics ... 33

4.2 Results ... 34

4.2.1 Multiple Linear Regression ... 35

4.2.2 Demographic factors and WTP ... 36

4.2.3 Psychological Determinants and WTP ... 37

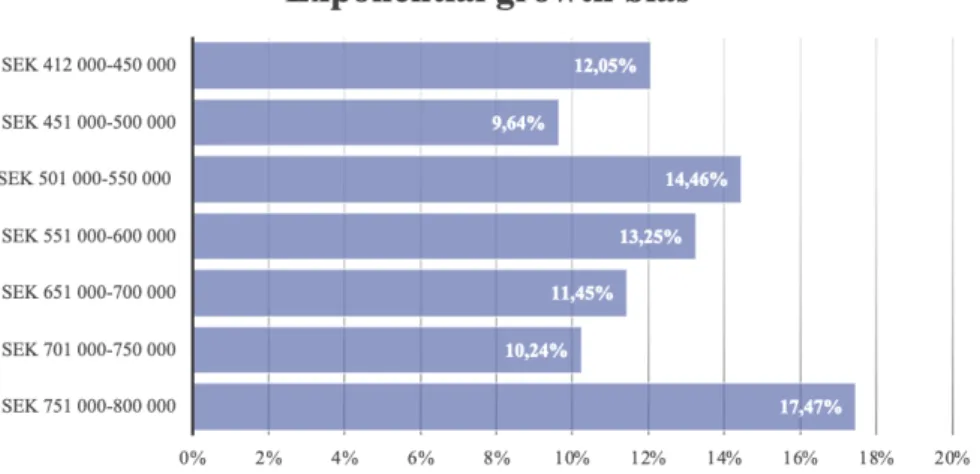

4.2.4 Misperception of Exponential growth ... 38

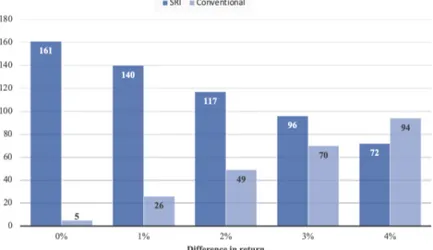

4.2.5 Selection of funds ... 39

5. Analysis ... 40

5.1 Willingness to pay ... 40

6. Conclusion ... 44

7. Discussion ... 45

7.1 Ethical and social aspects ... 45

7.2 Evaluation of the study ... 46

7.3 Future research and suggestions ... 48

References ... 50

Appendices ... 56

Appendix 1 - Survey ... 56

1

1. Introduction

This section intends to introduce the idea of socially responsible investments and the premium pension system. Further, it presents the problem, purpose and delimitations of the study.

1.1 Background

The interest in Socially Responsible Investments (SRI) has escalated in the past decade as more investors recognise the relevance of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors on the market (HSBC, 2020). It would be an understatement to claim that people are becoming more conscious of their influence on their external environment and increasingly consider which industries and companies are indirectly financed through one’s investments. Recognising how individual behaviours and decisions can impact the holistic perspective may pave new paths and enable the society at large to comprehend what individual steps one can take to reduce negative indirect consequences of one’s decisions. As consumers have become more aware, showing that they value companies who grow responsibly and not at society’s expense, an increase in the importance of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) can also be seen (Auer & Schuhmacher, 2016). Henceforth, to satisfy the consumer’s continually growing needs regarding sustainability and social responsibility, existing markets have been forced to adapt, and new markets have emerged (Auer & Schuhmacher, 2016). One example of these emerging markets is that of SRI.

To align one’s investment decisions with one’s values, integrating social and ethical criteria as well as perceived non-monetary value, is an approach that has been described with various terms over the years. Broadly speaking, SRI can be defined as an investment activity that identifies companies with high CSR using ESG criteria (Renneboog et al., 2008). SRI speaks to the fact that an investor’s utility function may have multiple attributes, including non-financial terms, indirectly indicating a willingness to pay for these types of investment products. This deviates from what is considered views of traditional finance (Bauer & Smeets, 2015). SRI assets are continuing to rise globally, with some world regions displaying more substantial growth than others (GSIA, 2019). From 2014 to 2018, SRI have increased from 18% to 26% in the US. Correspondingly, in 2018, out of the country's assets under professional management, responsible investing accounted for 51% in Canada. In Europe, the share of responsible investments fell from 59% to 49% during the period. Arguably, this could be due to the market of these investments having matured and there now exists higher requirements for what can be defined as sustainable rather than a reduced interest (GSIA, 2019).

2

Moreover, global initiatives are increasingly being taken to transform society in a more sustainable direction. The business community and the financial sector are singled out as system-critical actors to achieve the high goals set for sustainable development in, for example, Agenda 2030 and the Paris Agreement. As a result, to achieve the goals, the commitments of the European Union have increased. At the EU level, sustainable finance aims to support the achievement of the targets of the European Green Deal. Complementary to public funds, this is done by channelling private investments to ultimately transition into a resource-efficient, resilient, and inclusive economy. The European Green Deal is a growth strategy that aims at making Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050 by mobilising sustainable investments of at least €1 trillion over the next ten years. International efforts are also being coordinated by the European Commission through the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF). The ultimate goal with this platform is to aid in scaling up the mobilisation of private capital towards sustainable investments by strengthening international cooperation and coordination on issues considered essential for private investors to recognise and grab sustainable investment opportunities.

Consequently, sustainability in the financial market is now also a priority in the Swedish Parliament. The primary goal is that the Swedish financial system will contribute to sustainable development by taking ESG factors into account. An example of the increased requirements regarding sustainability issues in Sweden is the new legal requirement since the 1st of November 2018 (Konsumentverket, 2017), stating what sort of sustainability information that managers of mutual funds and investment funds, aimed at consumers, must provide to the public.

The importance of SRI investments in Sweden emerged in the 1960s when the ethical investment fund AktieAnsvar Aktiefond was established in 1965, where the administration is based on the conviction that knowledge and focus on the long-term leads to good results (AktieAnsvar, 2007). The Church of Sweden contributed significantly to the initialisation of SRI in Scandinavia, and in 1980 Svenska Kyrkans Värdepappersfond was set up through a joint venture. Shortly after, four ethical funds were established by the joint venture during the 1980s. From the mid-’80s and onwards, private actors seized the leading role of SRI progression. Changes in societal values and norms shaped the development of socially responsible investments, and Scandinavian investors gradually incorporated more and more concern for environmental factors into their investment decisions (Bengtsson, 2008). Regulatory requirements were formed to support these developments. For example, in January 2002, a regulation requiring Swedish national pension funds to incorporate ethical and environmental aspects in their investment policies was established (Renneboog et al., 2008), demonstrating the importance of SRI.

3

Another authority forming stricter rules concerning sustainability is the Swedish Pension Agency. The funds available for selection for the Swedish premium pension (PPM) are carefully selected, and the sustainability demands for these funds are now higher than the demands for the fund market outside PPM. A minimum requirement for funds distributed at the PPM fund market is that the fund manager must have signed the Principles for Responsible Investments (PRI) supported by the United Nations (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2020a). For their PPM fund selection, pension beneficiaries are able to use filters to find more sustainable funds or to opt out of certain industries. The funds displaying sustainability markings are funds meeting the criteria according to guidelines from the ethics committee for fund marketing (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2020a). For example, stating that sustainability aspects are crucial for the trustee’s choice of company and checking the mark for Morningstar’s grading for low CO2 risk. The PPM is a part of the national public pension, and yearly, 2.5% of one’s pensionable income and other taxable benefits are allocated to the premium pension. The pension beneficiary can choose to allocate their capital in their own selection of five funds or to stay with the pre-selected alternative AP7 Såfa (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2020b). Thus, the Swedish pension beneficiaries have the opportunity of selecting five funds of their choice into their portfolio, actively impacting their later life.

Regarding pension beneficiaries’ outlook of the future, some data suggests that the way beneficiaries think about their retirement and later life are detached from their pension saving decision. People tend to focus more on the present and the near future before long-term saving. Their inability to predict what their retirement might be like influences their present pension actions (James et al., 2020). Moreover, individuals show tendencies to disregard the compounding of exponential growth to a partial degree; this systematic underestimation is referred to as Exponential-growth bias (Stango & Zinman, 2009). This bias influences an individual's decision to save over long time-horizons, for instance, saving for one’s retirement (Goda et al, 2019). This indicates that pension beneficiaries’ might find it challenging to grasp the importance of their investment and the actual impact that it could have on their future. Thus, an optimal saving decision cannot be made if one is incapable of accurately estimating how that capital will grow over time.

Even though the research regarding socially responsible investors in different interpretations is quite explored, the research regarding pension beneficiaries decision-making process and willingness to pay for socially responsible investments is quite restricted. These differ since pension beneficiaries mirror the general public more as not all individuals regularly make investment decisions. Pension savings also have a more long-term outlook than certain short-term investments. Thus, this is an interesting and important area to explore further. The present study will investigate the socio-demographic and psychological determinants of Swedish pension beneficiaries in relation to the willingness to pay for socially responsible investments. It will also investigate if they indicate any misperception of

4

exponential growth, something that may have a huge impact on one’s retirement savings when selecting one’s pension portfolio. The study will be based on an online questionnaire, asking the respondents about the variables in question.

1.2 Problem

The field regarding pension beneficiaries' relation to SRI is still progressing. As markets are forced to adapt to continuous changes in different ways, understanding the influences on investment decisions are becoming increasingly important. As previously mentioned, investment decisions are strongly influenced by individual preferences and perceived non-monetary value. This suggests that, at least to a certain degree, investment decisions may not primarily be based on yielding financial utility but instead to hold portfolios that are consistent with one’s social values and the aim for nonfinancial utility. Further, this indirectly insinuates a higher willingness to pay, in terms of being willing to forgo a higher return or pay a premium, to invest in line with one’s values.

If there, in fact, exists financial performance differences between SRI and conventional investments has been the topic of several studies. Many of these studies show that there is no significant difference between the two (e.g., Bauer et al., 2005; Statman, 2000). However, as the significance of non-financial motives for SRI is demonstrated by, for example, the willingness to accept an expected financial underperformance (Riedl and Smeets, 2017), the aspect of willingness to pay is still relevant in this context and a highly interesting issue to investigate. Moreover, as mentioned above, dealing with quantitative information is a struggling matter for individuals, as they systematically underestimate exponential growth. As individuals tend to have difficulty visioning the distant future, and this can be seen in their pension savings, the misperception of exponential growth is an interesting and urgent matter to investigate concerning pension savings.

Based on previous statements, it is evident that the integration of criteria of social and ethical notions, as well as the perceived non-monetary value in the decision-making process, is highly relevant in this case. Hence, to gain more knowledge regarding how different variables influence the pension beneficiaries' decision to invest socially responsibly, it is necessary to look at the impact of socio-demographic characteristics as well as psychological determinants. The present work tries to fill an existing gap in the literature by examining these areas in relation to the willingness to pay for SRI. Further, it will investigate if any misperception of exponential growth is present. This is a fascinating matter to examine, especially if an individual demonstrates a tendency to underestimate compound growth but state a willingness to pay to invest socially responsibly. This may indicate that the individual

5

does not comprehend the consequences a slightly lower annual return could have on one’s pension capital.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to examine the socio-demographic and psychological determinants of pension beneficiaries' and the influence of these variables on the willingness to pay for socially responsible investments. The study will additionally explore the tendency to underestimate exponential growth in one’s pension savings.

The following research questions will be examined:

● Do socio-demographic variables have a significant impact on the willingness to pay for socially responsible investments?

● Do the pension beneficiaries’ attitudes and beliefs affect their willingness to pay for socially responsible investments?

● Do pension beneficiaries demonstrate a tendency to underestimate exponential growth?

1.4 Delimitations

The issue of whether socially responsible investment alternatives actually result in higher costs or not will not be examined. The study will focus on Swedish citizens belonging to the Swedish general pension system. The factors that will be analysed are relevant for the investigation of willingness to pay for socially responsible investments according to previous research. The analysis of the participants’ perception of exponential growth will be restricted to if they actually underestimate exponential growth or not.

6

2. Literature Review

This section reviews previous studies and theories examining investment behaviour in relation to SRI, willingness to pay and Exponential growth bias.

2.1 Socio-demographic variables

Previous research studying demographic characteristics and how these affect the decision to invest socially responsibly is mainly focused on individual investors allocating their capital in socially responsible (SR) mutual funds. Along with other social trends, the movement of SRI first became apparent in the 1960s as investors became more aware of the social consequences of their investments (Renneboog et al., 2011). While a limited number of studies prior to 1991 examined the institutions’ use of CSR criteria, Rosen et al. (1991) claim to be the first to study the criteria used by individual investors who allocate their funds to companies supporting social objectives. Based on a survey on 1493 individual investors with capital allocated in socially screened mutual funds, Rosen et al. investigated three main issues from the data collected, one of these being the demographics of socially responsible investors. The authors concluded that SR investors generally have a greater level of education and a lower level of income.

Similar to Rosen et al. (1991), several authors conclude that investors engaged in SRI have a greater level of education than conventional investors. For example, Mclachlan and Gardner (2004) studied differences in conventional and SR investors by distributing questionnaires to clients of Australian investment service companies. Ultimately 55 respondents were labelled as conventional investors and 54 as SR investors, yielding a response rate of 31%. They found no relationship between investor type and age, gender or education level. Further, the results found no significant relationship between investor type and income.

Over time, multiple studies on SR investor demographics have generated different, and sometimes, contrasting results. While in some studies, gender is not found to be a distinct factor in differentiating one investor from another (Mclachlan & Gardner, 2004; Williams, 2005), other studies state that SR investors are typically female (e.g., Dorfleitner & Nguyen, 2016).

In line with this, Delsen and Lehr’s (2019) results suggest that women tend to have stronger preferences for sustainability relative to men. This proved significant at a 99% confidence level, with women demonstrating a higher sustainability preference at 0.163 units compared to men. Further, they found that an increase in preference can be seen as women age as well as with educational achievement. Their data on pension beneficiaries’ preferences for sustainable investments were collected through a

7

questionnaire survey fielded in the Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social sciences panel in the Netherlands on pension beneficiaries’ preferences for sustainable investments. The sample consisted of 5 034 individuals.

One study examining socio-demographic characteristics of socially responsible investors in Sweden is the study by Nilsson (2008). Nilsson constructed a survey and randomly selected 2000 people owning a portfolio with at least one SRI product and 200 people owning no SRI products. The final sample size consisted of 439 Swedish SR investors and 89 conventional investors, yielding a response rate of 24%, which could be considered quite low. Consistent with some previous research, Nilsson found that both gender and education proved to have a considerable impact on the proportion of their investment portfolio invested in SRI funds. Women showed a greater tendency to invest a large part of their portfolio in SR mutual funds compared to their male counterparts. The subjects absent of a university degree invested less of their portfolio in SRI funds. Additionally, income, age, and place of residence did not prove to have a significant influence on SRI behaviour. Worth noting, however, is that the results regarding age can be misleading due to the high average age of the sample, with 60% of the subjects being 61 and older and should be interpreted with caution.

Presented research displays contrasting results regarding the socio-demographics for socially responsible investors. Several of the studies reviewed have, however, found gender and education to have a significant impact.

2.2 Psychological Determinants

Several studies, for example, Williams (2005) and Nilsson (2008), suggest that the main difference between a socially responsible investor and a conventional investor are their attitudinal profile and their values rather than their demographic characteristics.

By combining and analysing survey data, administrative data, and the behaviour of subjects in incentivised experiments, Riedl and Smeets (2017) shed light on why investors hold socially responsible mutual funds. The experiments and the survey had a total response of 2 800 conventional investors and 405 socially responsible investors. The administrative data was collected from a mutual fund provider in the Netherlands, offering a variety of both conventional and socially responsible mutual funds. Through the administrative data, information about 3 382 socially responsible investors and 35 000 conventional investors was gathered. This data was merged with the outcome of their survey and the experiments.

8

Looking at the investors’ social motives for investments, they distinguish between intrinsic social preferences and social signalling. As explained by Riedl and Smeets, intrinsic social preferences are prosocial motives that do not furnish any future benefit to the individual itself, whilst social signalling considers the motive to show others that one invests in a socially responsible manner to improve their social reputation. Strong social preferences are stated to positively influence the probability of investing in SRI funds, as well as signifying the impact that social preferences have on the decision whether to buy an SRI fund or not. Furthermore, findings state that investors with weak social preferences and strong signalling, who hold SRI funds, invest a smaller portion of their portfolio in SRI funds. This implies that investors with weak social preferences invest in SRI funds only if this investment decision is found to impact their reputation positively. By investing a smaller fraction of their portfolios in socially responsible funds, investors can signify that they invest in SRI and thereby emit a positive image. Findings from Riedl and Smeets study further suggests that individuals who have positive beliefs and views regarding SRI funds' social impact are more likely to hold such funds, in line with what is called perceived consumer effectiveness (PCE). A limitation to the research could be their classification of a socially responsible investor, which is an investor who holds at least one socially responsible mutual fund.

Perceived consumer effectiveness was initially considered to be a measure of the individual’s attitude itself and was modelled as a direct forecaster of cognisant environmental behaviour (Antil, 1984; Kinnear et al., 1974). Other studies suggest that PCE and attitudes can be modelled as two distinct constructs (Allen, 1982; Ellen et al., 1991). These studies explain PCE as an estimate of the degree to which personal consumption activities contribute to a solution to the concerned problem. Further, Berger and Corbin (1992) investigate if PCE moderates the relationship between individual consumer behaviours and overall environmental attitudes by using data from telephone interviews with 1521 individuals, supplied by a major Canadian polling company. This data presented the degree of environmental concern amongst Canadian adults. The results show substantial support for the hypothesis that PCE abates the degree of the relationship between individual consumer behaviour and environmental attitude. It demonstrates that PCE is a notably influential moderator of the relationship between environmental attitude and consumer behaviour. The authors conclude that the decision of whether an individual will act on the environmental concerns in the consumer marketplace or not, is clearly influenced by the individual’s self-perceived efficacy in combating environmental problems.

Investigating a similar matter, Nilsson (2008) studied mutual fund investments and the impact of pro-social and financial perception on SRI behaviour. The main elements investigated were PCE, pro-pro-social behaviour, trust, and perception of financial risk and return. Similar to results of previous studies, Nilsson concludes that investors who believe that their private investment decisions could help solve

9

environmental, social and ethical issues allocate their capital more in socially responsible investments, in contrast to investors who do not share these beliefs. These results were highly significant, with a p-value of 0.000. Pro-social attitudes were also found to have a significant impact, with a p-p-value of 0.015. Individuals were found to be more likely to invest a greater proportion of their portfolio in SRI mutual funds if they had higher levels of pro-social attitudes towards issues addressed by SRI. Contrastingly, Riedl and Smeets (2017) findings suggest that social preferences and beliefs are less important for the decision of how large amounts of the individual’s equity investments will be distributed in SRI equity funds. This was concluded after their regression analysis showed that there was no significant relationship between social preferences and the fraction of the portfolio consisting of SRI funds. Furthermore, Diouf and Hebb (2016) analysed secondary quantitative and qualitative data from 2012 collected by Desjardins1, this data is complemented by data from 10 semi-structured interviews to gain further insight into SR investment behaviour. The authors conclude that the decision to invest socially responsibly is dependent on the individual’s beliefs, motivations, desires and goals, as well as the socio-cultural context whereupon they reach investment decisions. However, they also find that the positive attitude of an investor towards socially responsible investments does not necessarily lead to a formal investment decision, demonstrating the complexity of decision making and investors “walking the talk”.

Straughan and Roberts (1999) administrated a questionnaire to a convenience sample of 235 traditional and non-traditional college students in the US. The sample consisted of 66% male respondents and the mean age was 22 years. The authors suggest that the two most important factors for predicting environmentally conscious consumer behaviour are perceived consumer effectiveness and altruism (i.e., concern for the welfare of others). In other words, if an investor feels that their choice of investment product and their actions somehow increases the wellbeing of others, they should be more likely to invest in SRI. The authors find the effects of altruism, PCE and environmental concern to be significant to the investment decision. Moreover, they find that psychographics outperforms demographics as an instrument to determine the green consumer profile. Three sets of values have been identified associated with environmental attitudes; egotistic, altruistic, and biospheric, where egotistic values focus on self and self-oriented goals, whereas altruistic values focus on other people, and biospheric values focus on the well-being of living things (Stern & Dietz, 1994; Stern et al., 1995). According to the concept, each set of values can result in attitudes of concern for environmental issues, and when activated, this leads to behaviour.

Palacios-González and Chamorro-Mera (2020) investigated Spanish investors’ attitudinal profile and beliefs towards socially responsible investments. Spanish citizens aged 18 and over who held a financial savings or investment product were surveyed for the study. Face-to-face and online questionnaires were

10

conducted, and ultimately 415 valid questionnaires were analysed. Results show that investors with a greater inclination to invest their wealth socially responsible show a different attitudinal profile than more conventional investors. They perceive, to a greater extent, that this type of investment is effective and gives personal gain. A limitation of this study is that there usually exists a socially correct response bias. This can cause some responses in their questionnaire to be misleading and overvalued due to subjects trying to appear “better” in a socially correct sense. To bear in mind is also that a higher percentage rate (47%) in their sample consists of young people. This group's percentage in this sample is higher than in the population being studied.

Apostolakis et al. (2018) investigate the effect of pension beneficiaries’ attitudes on the decision towards responsible investments on 673 participants derived from a panel of active and retired members from a Dutch pension administrative organisation. The participants were given information regarding investments contained in a hypothetical portfolio and that choosing an SRI portfolio would result in a slightly lower pension due to additional administrative costs. Giving the respondents a hypothetical scenario and providing the ability to choose, they asked the members about their intention to invest in a new SRI portfolio. The authors use the perceived consumer effectiveness and the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) to examine the extent to which these attitudes predict the intention of pension beneficiaries to invest in a socially responsible investment portfolio. The theory of planned behaviour (TPB), as explained by Ajzen (1991), distinguishes between three types of beliefs: normative, behavioural and control. In addition, Ajzen also distinguishes between the associated constructs of attitude, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms. Attitudes, perceived control, and subjective norms are found to predict behavioural intentions. As the attitude and the subjective norms become more favourable and the envisioned control increases, the intention to perform the specific behaviour also enhances.

The findings of Apostolakis et al. (2018) are in line with the TPB, as the behavioural intention to adopt socially responsible investment behaviour is found to be predicted by attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioural control. Furthermore, they also conclude that PCE is an important predictor of socially responsible investing behaviour. One limitation to their study is the fact that it was made in the Dutch healthcare sector, and women represent 70% of the workforce in this sector. Furthermore, a response rate of 11% may be considered insufficient.

Borgers and Pownall (2014) test whether the utility acquired from investing in socially responsible pension investments is considered positive for the general public. By using data from a large sample of Dutch households gathered in the first quarter of 2011, they investigate environmental and social attitudes. The authors asked the respondents how much they value applied socially responsible

11

investment screens and if they are willing to give up a small part of their pension to apply the screens. Delimiting their study, they chose to focus on household members of at least 20 years of age, resulting in 1766 relevant survey responses for the study.

A significant share of pension beneficiaries is found to obtain a positive utility from social screens in their pension investments. The majority of the respondents unquestionably value social responsibility in their pension decisions, and 55% preferred the screened portfolio. Furthermore, it was established that over one-third of the beneficiaries in question did not incorporate their preferences into their financial decisions and that absence of financial refinement could partially explain the matter. A natural problem with the design of the survey is the fact that it did not observe the original pension investments of the pension funds, and the questions reflect simplified versions of reality. Similar to Borgers and Pownall’s results, Delsen and Lehr (2019) find that sustainable pension fund investments are considerably favoured, and 75% of their sample of pension fund participants in the Netherlands aged 40 and over, at least to some extent, favour sustainable investments.

The results from a field experiment made by Bauer et al. (2019), comparing Dutch pension fund participants’ SR investment decisions showed that 67.9% out of the 1669 participants support an increase of sustainable investing of their pension savings. The choice to invest more sustainably is found to be linked to social preferences, and it is not determined by financial beliefs. In addition, the majority of the subjects believe that financial returns do not have to be negatively affected by a greater focus on sustainability or are at least unsure if it does. Even amongst the participants who expect negative effects on return, a majority would still want their pension savings to promote sustainability, where strong social preferences are found to be a key motivation. It should be emphasised that this study by Bauer, Ruof and Smeets is not published and is still considered a working paper.

Looking at Swedish pension beneficiaries, Jansson et al. (2014) measure pension beneficiaries’ preferences for socially responsible investments. A random sample that included 3500 Swedish residents between the age of 18-64 years was selected. A questionnaire was sent out to the participants by mail, and the participants had to mail back their responses. The study received a total response rate of 33.2%, which corresponds to 1119 usable questionnaires. 41% of the respondents had a university degree, 50.5% were women, and the average age was 52.1 years. Jansson et al. (2014) find that the beneficiaries, on average, prefer that their pension funds engage in SRI. Additionally, self-transcendent value priorities and financial grounds are found to drive more heterogeneity amongst pension fund members in contrast to socially responsible investors. Furthermore, the variation of beneficiaries’ general commitment to social, ethical and environmental issues are not the only explanation found for the differences in beneficiaries' SRI preferences. The variation is also connected to differences in the

12

fundamental priorities of their values. People yielded positive correlations with variance in how firmly they prioritise self-transcendent values over self-enhancement. This is found to affect their social, ethical and environmental concerns and preferences for SRI.

A limitation to the study by Jansson et al. (2014) is the fact that they sent out the questionnaire by regular mail, and the participants had to mail back their answers. This might have affected the response rate since approximately two-thirds of the sample did not respond. Worth noting is that around 2014, collecting an e-mail or online-based survey would have been more efficient. Moreover, the estimated time to finish the questionnaire was 20-25 minutes, which may affect the results due to the respondents’ motivation. Furthermore, the study does not mention when the questionnaire was made.

To summarise, the research regarding individual SR investors attitudes and beliefs are somewhat conflicting. However, most research agrees that perceived consumer effectiveness and the level of pro-social attitudes and beliefs seems to have a significant impact on the decision to invest in SRI. Furthermore, pension beneficiaries' interest in SRI appears to increase, and the intention to invest in SRI may be explained by attitudes, social norms and behavioural control. One study also suggests that there exists more heterogeneity amongst pension fund members in contrast to socially responsible investors due to self-transcendent values and financial grounds.

2.3 Willingness to pay for SRI

For a long period of time, it was common to assume that the willingness to pay (WTP) for socially responsible investment products was theoretically equal to zero. According to Bauer and Smeets (2015), this is because SRI should only be considered if they are deemed at least as attractive as conventional investments in regard to risk and return. Demonstrated below is empirical research questioning these beliefs. These reveal the magnitude of non-financial motives for socially responsible investments and, thus, indirectly, a willingness to pay for these types of investment products. In this study, willingness to pay will be synonymous with the willingness to forego financial return to invest socially responsibly.

Based on research regarding socially responsible investing, there is an indication suggesting that investors might be willing to pay to invest according to their values. Glac (2009) examined why some choose to invest socially responsibly, and some do not, using a questionnaire targeting undergraduate students studying business ethics or professional responsibility. In the end, 121 complete responses were received. Glac (2009) suggests, by studying individuals’ decision to invest socially responsibly, that individuals who have more expressive decision frames are willing to make larger sacrifices regarding return than investors who have a financial decision frame. The conclusion is drawn that the investors with expressive decision frames are therefore more willing to forego some financial return to

13

satisfy their psychological benefits. This study is likely to have produced biased results due to the nature of the participants’ field of study.

Worth mentioning is that there exist several studies providing evidence that SRI and conventional investments, on average, show no significant difference with respect to financial performance. Statman (2000) analysed the performance of socially responsible mutual funds and an index of socially responsible companies from 1990 through 1998. Information about the funds studied was taken from Morningstar, and the S&P 500 was used as a benchmark for performance. Results showed that there was no significant difference in performance between the conventional funds and the socially responsible funds. Furthermore, Bauer et al. (2005) review ethical mutual fund performance through data regarding 103 German, UK and US ethical mutual funds collected from an international database. To analyse the data, they used a multi-factor model based on four factors and a standard CAPM 1-factor model. The authors found no significant difference when comparing the return of socially responsible funds and conventional funds.

On the other hand, Riedl and Smeets (2017) investigated the distribution of return expectations for investors holding an SRI equity fund and investors not holding an SRI equity fund. This was investigated through a question measured on a Likert scale. Results suggest that socially responsible investors expect SRI to underperform compared to conventional investments both in turns of producing lower returns and Sharpe ratios as well as requiring higher administrative fees. It is thus suggested by the authors that investors are willing to accept an expected financial underperformance, as long as they have strong social motivations to do so. Thus, demonstrating that SR investors are willing to pay to be able to invest according to their social preferences, demonstrating the relevance of non-financial motives.

The argument made by Riedl and Smeets is further supported by the findings of Lewis and Mackenzie (2000), who examined if people were prepared to put their money where their morals are. They did this by surveying 1146 ethical investors in the UK, presenting them with conventional and responsible investments with diverse returns in order to examine if people are prepared to put their money where their morals are. The results indicate that the investors would not change their composition of SRI in their portfolio despite facing a lower return of 5% on their holdings, compared to 10% for non-ethical investments, indicating that they are more loyal when fund performance decays. Similar results were presented by Renneboog et al. (2011) regarding the money flows of socially responsible investments. Their findings show that SRI investors are less troubled by negative financial returns. The flows of SRI funds are substantially less sensitive to past negative returns, and the investors investing in SRI funds seem to derive non-financial utility.

14

Gutsche and Ziegler (2019) studied whether and which investors are willing to pay for socially responsible investments. They investigated this by basing their study on survey data composed of two stated choice experiments, an experiment designed to understand the subjects revealed preferences for different alternatives among German private financial decision-makers. In the two stated choice experiment, 1001 and 801 individuals participated respectively. Whilst analysing which investor groups that are willing to pay for sustainable investment products, they considered the relevance of individual characteristics such as values, psychological motives and norms. Gutsche and Ziegler made econometric analyses and latent class logit regression models. The results revealed solid declared preferences and a significant willingness to pay for sustainable investment products. Moreover, the mean willingness to pay for certified sustainable investment products were significantly higher (0.25 percentage points) than the mean willingness to pay for uncertified equivalents (0.112 percentage points). In addition to these results, their findings further suggest that investors with strong environmental awareness, who get high feelings of “warm glow” from sustainable investments, have a greater mean willingness to sacrifice returns for sustainable investment products. This indicates that respondents’ specific values, norms and psychological motives impact the mean willingness to sacrifice returns for socially responsible investment products.

Berry and Yeung’s (2013) study, based on a questionnaire measuring British ethical investors preferences, measures each investor’s gain in utility from a shift from large financial loss to financial improvement and a shift from poor to good ethical performance. A total of 82 respondents, out of the 192 individuals asked to do the questionnaire, completed the questions dealing with the level of investment in securities with various financial and ethical performance, whilst 65 participants completed the questions regarding investor characteristics. The authors reported that the sample consisted of 43.9% male and 56.1% female participants. In the questionnaire, the subjects had to allocate 100 000 British pounds across ten investment opportunities with diverse sustainability levels and financial performance. Investigating whether ethical investors were willing to sacrifice ethical considerations for financial reward, the results showed that the sample average utility gain from poor to good ethical improvement exceeded the subjects mean utility from an improvement of financial performance. However, the sample average obscured significant differences in willingness to sacrifice ethical performance for financial gain. Moreover, Berry and Yeung show that ethical investors behave differently regarding the sacrifice of ethical performance for financial reward, showing dissimilarities in the importance of financial return. A limitation to consider regarding the study is the fact that they used a postal questionnaire, which, as mentioned previously, might have impacted the response rate. Furthermore, it would have been interesting to know at what period the survey data was gathered in order to get a better interpretation of the results. Also, since the authors encouraged participation by

15

offering to donate £2 to the chosen charity of each individual who completed the questionnaire, the motivation of the participants may be questioned.

Furthermore, Webley et al. (2001), in their study regarding framing and mental accounts (how people mentally frame, evaluate and categorise economic outcomes and transactions) for ethical investors, concludes that ethical investing is based on identity and ideology and is not just a matter of financial return for ethical investors. Exploring the issue of what differentiates ethical investors from conventional investors, they used an experimental approach. There was a total of 56 investors that took part, equal parts ethical and standard investors. The age ranged from 30 to 88 years, and the majority of the participants were over 50 years old, which may result in a skewed outcome. The subjects were presented with different investment choices through a role-play consultation with a “virtual” financial advisor. Results showed that ethical investors were generally committed to ethical investing and were prone to keep those investments even if they performed badly or were ethically ineffective. This is in line with Arkes and Aytons (1999) conclusion that if ethical investments are important to individuals, they may be notably susceptible to sunk costs and escalation of commitment bias, sticking with their ethical investment.

Looking further into pension beneficiaries' willingness to pay, as previously mentioned, Borgers and Pownall (2014) investigate Dutch households’ attitudes towards socially responsible pension management. To investigate whether the beneficiaries get positive utility from investing their pension endowments more socially responsible, they asked the respondents if they were willing to sacrifice part of their pension income for social screens. Their study shows that about 50% of the respondents are willing to give up a “small part of their pension income” to invest in SRI pension funds. Furthermore, over 70% of the respondents are willing to give up a part of their pension income (between 1% to 5% per month compared to their current expected pension entitlement) for socially responsible pension funds.

Apostolakis et al. (2016) study pension beneficiaries’ willingness to accept a lower pension for investing in a portfolio that has socially responsible investment criteria and impact investment characteristics. Dutch pension beneficiaries, who were members of PGGM (the pension administrative organisation) and had a working relationship with the healthcare sector, were surveyed. In total, 985 complete questionnaires were collected. The respondents were asked about their preferences between an SR impact investment portfolio and a conventional portfolio and their preference for greater involvement and freedom of choice. Next, the subjects were given a hypothetical scenario where they had the opportunity to choose a socially responsible portfolio and asked if they were willing to pay to choose this portfolio. Results from the study suggest that respondents with higher product involvement have

16

on average, a more positive view of impact and socially responsible investments compared to the respondents with lower product involvement. Product involvement is also shown to have a positive influence on willingness to pay. Further, some evidence indicates that age, education and income are associated with willingness to pay.

Moreover, Apostolakis et al. (2016) show that a greater positive attitude towards SRI criteria and positive screenings are associated with a greater willingness to pay. Further, the authors found no evidence for the attitudes towards impact investments to influence the willingness to pay. Since the authors expected the attitude towards impact investment to affect willingness to pay, they explain that the results may have been perceived by the respondents as investment opportunities related to financial gains rather than social issues. Pension and social concerns were not found to have an impact on the willingness to pay, whilst respondents who are highly involved indicated a higher likelihood to pay the extra costs for SRI. A limitation to this study is that the sample concerns a limited group of people in the Dutch healthcare sector where the majority of employees are women, and the respondents might be more prone to invest in, for example, medical innovation.

A limitation for numerous studies regarding the willingness to pay for socially responsible investments is the fact that they do not measure actual behaviour, since the respondents are asked about their willingness to pay in hypothetical scenarios. On the one hand, these scenarios are hypothetical, and subjects are not exposed to any real monetary loss. On the other hand, it would be exceptionally difficult to perform an experiment or survey where the participant is faced with an actual financial loss, both in regard to getting individuals to participate but also due to research ethics.

2.4 Exponential growth bias

For long‐run choices such as retirement savings in PPM, exponential growth bias is predicted to be particularly important (Goda et al., 2019). People have problems dealing with quantitative data in an intuitive way and systematically underestimate exponential growth over time (e.g., McKenzie & Liersch, 2011; Tversky & Kahneman, 1971, 1973; Wagenaar and Sagaria, 1975). Excessive intertemporal discounting (i.e., future outcomes are discounted (or undervalued) relative to immediate outcomes) and absence of will are two out of various explanations that have been proposed as a reason why people are not saving enough (e.g., Laibson 1997; Thaler and Benartzi 2004). Explanations like these implicitly assume that there exists a basic understanding in people's minds of how savings grow over time. However, other studies by Wagenaar and Sagaria (1975), and McKenzie & Liersch (2011), show people’s fundamental misunderstanding of the growth of savings.

17

The study by Wagenaar and Sagaria (1975), is a bit older but is still interesting to this day. The authors examined how the subjects of the study perceived exponential growth represented by numbers and by graphs. Subjects of the three first experiments were undergraduate students, whilst the subjects in the last experiment were working professionals. Results show that all groups of students, in all circumstances, showed considerable underestimations of growth and that the misperception of exponential growth is not reduced by presenting the data graphically instead of numerically. The overall results suggest that more sophisticated subjects actively try to counteract the effect of underestimation, however, they were still not able to affect their response. Wagenaar and Sagaria conclude that the effect of underestimation appears to be general, and it is not decreased by having daily experience with processes of growth.

McKenzie and Liersch (2011) illustrates the phenomenon of the misunderstanding of savings growth in the context of retirement savings behaviour. Although compound interest is a basic economic concept, causing savings to grow exponentially, the findings of McKenzie and Liersch implies that a majority of students with an undergraduate degree have the inaccurate perception that savings grow linearly. Thus, this study’s subjects grossly underestimate the amount of capital they can accumulate until the time of their retirement. One of the experiments conducted in this study used surveys answered by 99 undergraduate students in groups of five in a laboratory setting. The subjects were tested on their intuition about the growth of their hypothetical retirement savings growth over a span of 40 years. The students were randomly assigned to either make an educated guess without aid or calculate the answer with the aid of a calculator and were given two scenarios. In the first scenario, the subjects were asked how much money they would have acquired in their savings account over varying amounts of time, ranging from 10 to 40 years, considering that a given fixed deposit was invested every month and the given annual interest rate was certain. In the second scenario, the students were asked how large of a monthly deposit they would have to make to reach their goal in 40 years given an annual fixed interest rate as well as the interest rate they would need to reach their goal given a fixed deposit.

Of the questions covering these various time horizons, amounts of monthly investments and rate of return, on average, 90% of the subjects underestimated their future savings. In addition, as mentioned previously, the authors found that the subjects, rather than thinking their savings would grow exponentially, expected their savings to grow linearly. The underestimation of the growth in their hypothetical retirement savings was palpable in all of the given scenarios. The subjects in the experiment by McKenzie and Liersch seemed to apply the interest just once, on the total amount deposited, ignoring the time value of capital (money invested earlier accrue more interest) which led to even more significant miscalculation errors. According to Wilson (2012), the kinds of focus groups that

18

McKenzie and Liersch (2011) used are not without their faults, some drawbacks include biased results, problems with dominant personalities and outcomes highly dependent on the moderator.

Moreover, the misperception of exponential growth has been demonstrated in other domains as well. Evidence was provided by Stango and Zinman (2009) that underestimation of exponential change affects financial outcomes for households, such as less saving and more borrowing. To reach this conclusion, they used data from surveys about consumer finances made in the 1970s and 1980s by The Federal Reserve, which asked the respondents to estimate the cost to repay a 1000-dollar purchase in 12 monthly instalments. The authors state that this specific data was used since it provides empirical evidence on payment/interest bias which is nationally representative. Furthermore, subjects were asked to provide the interest rate implied by their estimation. The study may be questioned considering the older, secondary data used.

Results showed that 98% of the respondents reported very low interest rates, and the authors consider this difference between implied and actual interest rate a measure of payment/interest bias. Payment/interest bias is described by the authors as the systematic tendency to underestimate a loan interest rate given the information about the maturity, a principal or monthly payment. Payment/interest bias is generated from exponential growth bias, which is the pervasive tendency to linearise exponential functions when evaluating them by instinct. The results also indicate that payment/interest bias is correlated with saving, borrowing and portfolio choices. Furthermore, future value biases are shown to be generated through exponential growth bias. Future value bias is explained as the tendency to consistently underestimate a future value given the rate of return, the time horizon and a present value. They ultimately conclude that future value bias causes the systematic underestimation of long-term savings by consumers.

In general, studies find that individuals tend to underestimate exponential growth. Further, individuals demonstrate a tendency to simplify estimations by linearising exponential functions or even apply the interest once to the total amount deposited. These underestimations lead to people grossly underestimating the amount of capital accrued until retirement, indicating that people may not understand how small differences in return can affect their pension savings.

2.5 Hypotheses

Based on the results from previous studies made, the following hypotheses were developed: H1: Men will demonstrate a lower WTP for SRI compared to their female counterparts. H2: Subjects with a higher level of education will be more willing to pay for SRI. H3: PCE positively influences the WTP for SRI.

19

H4: Higher concern for ESG-related issues will result in a higher WTP for SRI.

H5: Strong altruistic values (environmental attitude) positively influence the WTP for SRI. H6: Individuals tend to underestimate exponential growth.

20

3. Methodology

This section focuses on the approach and methodology of the study and its strengths and limitations.

3.1 Approach

In order to perform social research, one must decide whether to use an inductive or deductive theory. The most common way to connect social research and theory is represented by deductive theory, which is mostly connected with quantitative research (Bryman, 2016). Researchers use information that is already known about a specific research topic to develop a hypothesis or several hypotheses which then must be tested through an empirical investigation. If one instead uses the opposite of a deductive theory, namely an inductive theory, the collection of data is made in order to develop a theory or to create the base for a law (Bryman, 2016). The inductive theory is therefore mostly connected with qualitative research.

One could ask whether a natural science model is proper to use in studies made on the social world. Three different philosophical positions can be taken, namely positivism, realism and interpretivism (Bryman, 2016). For decades, the dominating philosophical position has been positivism. Positivism encourages the use of natural science methods while studying social reality, and elements of both deductive and inductive approach are entailed. Realism believes that social science and natural science should and can use the same methods whilst gathering data and explaining. There are two different kinds of realism, namely Critical realism and Empirical realism (Bryman, 2016). Empirical realism states that one can understand reality through the use of proper methods. It is often assumed by realists that there is an almost perfect conformity between reality and the term used to describe it. Critical realism states that reality can only be understood by the identification of structures that create different events and occasions.

In Interpretivism there is an essential difference between the subject matter of social science and natural science. Therefore, an alternative research process is necessary which reflects the peculiarity of humans compared to the natural order, and it demands that the individual explanation of social action should be kept by the social scientists (Bryman, 2016). Therefore, interpretivism contrasts with positivism.

Whether to do quantitative or qualitative research whilst investigating a specific matter is a choice one must make. The quantification in the data gathering and analysis is underlined by the quantitative research strategy, and the principal orientation to the relation between the role of theory and research is deductive. The data gathering is numerical, objective and the position is mostly characterized by

21

positivism. There exist several types of analysis methods that can be used on the data collected. The univariate analysis examines one variable at a time and in order to show clear numbers for the variables tested, diagrams and frequency tables are often used. The bivariate analysis looks at two variables and analyses whether there exists a correlation between the two. This analysis can be accomplished through correlation statistics and regression analysis (Bryman, 2016).

Qualitative research is instead interpreted as a research strategy that focuses on words rather than quantification of the analysis and the data collection. The relationship between theory and research is interpreted by the generation of theories, which is then characterized by an inductive approach. Qualitative research rejects the implementation of natural science since they emphasize the importance of how individuals construe their social world. They embrace the view that individuals' creation of social reality is a constantly shifting developing property. Qualitative research is therefore characterised by interpretivism and constructionism (Bryman, 2016), in contrast to quantitative research.

This study uses a deductive theory and the philosophical positions taken is positivism with some elements of realism. Several hypotheses are developed on the basis of previous research and what is already known. Additionally, certain motives and attitudes that are assumed to exist are investigated. Further, the study will rely on empirical social statistical data collected through an online questionnaire and a bivariate analysis will be applied to the data collected. This analysis was chosen since the purpose of this thesis is to investigate several socio-demographic and psychological determinants of pension beneficiaries and if these variables impact their decision to invest in SRI, their willingness to pay for SRI and their demonstrated exponential growth bias.

3.2 Data collection

3.2.1 Survey

The quantitative study was conducted in the form of an online questionnaire. There are two different approaches to the collection of empirical data, these approaches are typically primary and secondary data. Primary data is collected by the researcher during the investigation, whilst secondary data has been collected at an earlier stage and is available to the public through different documents or in databases (Bryman, 2016). Since this is a study that investigates Swedish pension beneficiaries’ socio-demographic factors and psychological determinants in relation to questions regarding SRI, new empirical data needs to be gathered to study the matter. Consequently, primary data is obtained. With the use of primary data, the data collected is adapted to the research questions and the aim of the investigation, which is advantageous.

22

For the collection of data needed for this study, an online questionnaire was developed and distributed. This procedure is both a time-effective and a cost-efficient way to gather data. With an online questionnaire, one can reach people all over the country which may also result in a larger number of respondents. On the other hand, the respondents do not have the opportunity to ask us questions in order to interpret the questions in the questionnaire correctly. The honesty among the respondents’ can therefore be questioned (Bryman, 2016).

To confirm that the survey questions were clearly formulated and if the design was pleasant and easy to follow, the survey was tested on a focus group. As a result, this enabled increased credibility of the survey (Bryman, 2016). Chosen for this focus group were 15 people, both students and more senior members. The participants in the focus group mostly had questions and feedback regarding the formulation of the questions asked and the overall design of the questionnaire. In order to create and perform the survey, a program called Qualtrics was used. A total of 18 questions were asked, it was voluntary for the respondents to participate in the survey, and no one was paid to participate. Information regarding the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was provided to the participants. The response time to complete the survey was estimated to be 9-12 minutes, and all questions were given a number in order for the participant to know how many questions were left to complete. Information concerning the estimated response time and the number of questions was presented to the participants in an introductory text (see Appendix 1) before the survey was commenced.

The questions in the survey were designed to fit the three research questions of the thesis. Since the study seeks to investigate whether socio-demographic factors and attitudes impact the willingness to pay for socially responsible investments, the survey started with simple questions regarding these factors. The survey continues with questions regarding attitudes, willingness to pay and perception of exponential growth. One of the most common formats for measuring attitudes is the Likert scale. The Likert scale is a multi-indicator of a set of attitudes relating to a particular area. The respondents are asked to select their level of agreement with a statement on a typical rating scale. Likert scale is one of the scales that use verbal statements, and it typically allows responses from a five-point scale going from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Although other formats like seven-point scales are sometimes used (Bryman, 2016), this study uses only five.

The question of whether results may be better (have higher mean scores) if a different scale format had been used is an interesting matter to investigate. Looking at previous research regarding this matter, it appears to be that a rating scale with more options produces slightly lower scores. Furthermore, none of the different formats of scaling is less desirable whilst obtaining data that will be used in regression analysis. Thus, either a five-, seven- or even 10-point scale are all equivalent for analytical tools (Dawes,

23

2008). Ultimately, the Likert responses in the survey were formulated in the following way: strongly disagree, partially disagree, neither disagree nor agree, partially agree, strongly agree.

The survey also asks the respondents how much return they are willing to forego to invest sustainably. The options range between 0% to 5% in lost return per year. The respondents also had to make five different funds choices, with two funds to choose from in each of the five questions (Appendix 1). The choice was between a socially responsible fund and a conventional fund. The difference in return ranged from 0% to 4% between the funds, which differ from the range in the previously asked question. This is because the survey would take too much time to complete if six fund choices were implemented instead of five. Furthermore, in the PPM portfolio, one can only hold five funds.

3.2.2 Population and selection

As the aim of this study is to identify particular patterns influencing the preferences for SRI in the Swedish premium pension, the population of interest is Swedish citizens who are a part of the Swedish general pension system. Every person who has lived or worked in Sweden receives a general pension (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2020c). A non-probability sample represented the distribution of this survey, which may result in a skewed selection due to the fact that some quantity within the population had a higher probability of being selected. A probability sample is argued to give a better and more trustworthy sample since a probability sample is randomly selected (Bryman, 2016). However, it is not manageable to distribute this survey to every individual part of the Swedish general pension system, implying every Swedish citizen, whereby a non-probability sample was the only viable option. Due to this fact, sampling restrictions might appear in this study.

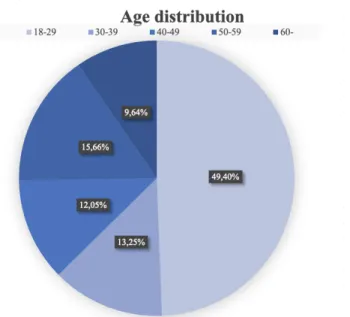

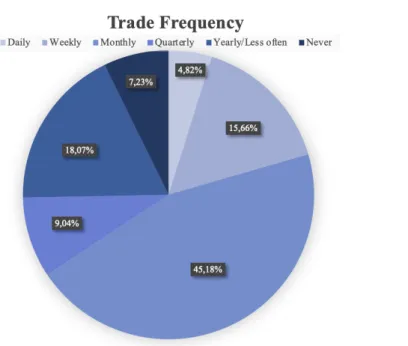

Further, the method of convenience sampling was utilised where each individual is left with the choice to participate in the study or not (Bryman, 2016). With the purpose of reaching a variety of individuals with diversified gender, age and investment experience, this was done by posting the survey on a number of social media platforms and forums such as LinkedIn, Facebook and Instagram. The data collection for this study is formed after the rules for GDPR and all participants consented to the collected data being used for a scientific purpose before answering the survey. Moreover, no sensitive information, as for example names or social security numbers, was collected. Ultimately, 166 individuals completed the questionnaire.

3.3 Empirical method

3.3.1 Cronbach’s Alpha

To test the internal reliability and consistency of the study and the survey questions, Cronbach’s alpha was used. Cronbach’s alpha is commonly used to test internal reliability, and it calculates the mean of