B

OTANICAL DIVERSITY IN FRAGMENTS

OF SEMIDECIDOUS FOREST IN WESTERN

ECUADOR

Ulrika Ridbäck

Denna uppsats är författarens egendom och får inte användas för publicering utan författarens eller dennes rättsinnehavares tillstånd. Ulrika Ridbäck

CONTENTS 3

ABSTRACT 4

INTRODUCTION 5 STUDY AREA 6 MATERIAL AND METHODS 8

RESULTS 9

DISCUSSION 13 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 16 REFERENCES 17 SAMMANFATTNING 18

ABSTRACT

Coastal Ecuador is a region with high endemism and the need to protect its biological diversity has increased because of serious changes of the natural vegetation. The purpose of this study was to explore the botanical diversity in small forest fragments and to compare the data with the diversity in a nearby forest reserve. Samples of all vascular plants except lianas, climbers and epiphytes were collected and registered in plots of 50 m2 in temporary flooded

and unflooded habitats. The abundance of trees and herbs is higher in the forest reserve, whereas the number of shrubs is higher in the forest fragments. The temporary flooded

habitats have a higher abundance of life forms compared to the non-inundated habitats in both study areas. The forest reserve has more species of vascular plants in both habitats and also higher species diversity. A large amount of flowering species inhabited the forest fragments.

INTRODUCTION

Western Ecuador, an area corresponding to a quarter of Sweden, is estimated to possess more than 5000 species of vascular plants, 20 % of which are endemic to that area. However, the area has experienced extensive deforestation. The primary forest was virtually undisturbed until the early 1960s, when roads started to penetrate the area (Myers 1986). Most of the original vegetation has now been converted into pastures and plantations, primarily of African oil palm, banana and teak. The combination of a high species richness, extensive endemism and major changes of the natural vegetation, has increased the need to protect the biological diversity in western Ecuador (Gentry 1995). Being a relatively limited area a large part of the earth’s collected species are disappearing forever, the area was one of the first to become recognized as a hotspot for international conservation. Some 15 years ago, the situation were summarized as follows (Parker et al. 1992): “Without the concerted effort by the national and local governments, military authorities, conservation organizations, and concerned citizens, these biologically rich forests – as well as the huge number of plant and animal species they support – will disappear from the earth within 20 years”. A biodiversity hotspot can be defined as an area where a concentration of endemic species are undergoing exceptional loss of habitat (Townsend et al. 2003).

Biodiversity is valuable, among other things because it provides us with food (Gaston 1998). It broaden the supply of genetic resources. In addition, many important components for medical purposes comes from the tropics, and also a huge share of material to industries. Everytime people take decisions in using resourses from the environment, it may result in loss of biodiversity, depending on how it is done. Wild organisms are serving functions in the ecosystems for free.

A large number of species in western Ecuador may have been exterminated during the last decades, but it is likely that many rare species exist as relicts in different forest fragments in the region (Gentry 1986). It is common that landowners save small remnants of natural forest on their properties. The human fragmentation of the landscape has created isolated

subpopulations of plant and animal species (Townsend et al. 2003). This fragmentation is likely to have strong effects on populations with naturally low rates of dispersal. A hope is that all remaining forest fragments together possess much of the original flora and fauna. If this is the case, will these species survive in the long term, or are they “living dead”, which slowly disappear because of inbreeding or difficulties to reproduce? A way to approach this question is to examine the species diversity and composition in an area with strongly reduced natural vegetation and to compare the results with conditions in another, larger and less disturbed area within the same climatic zone.

The tropics are in a class of its own with regard to its high species richness. These ecosystems are also the least studied, poorest known and most threatened (Gentry 1993). Comparative floristic analyses in tropical forests are therefore of scientifical value and may provide base line data for other kinds of ecological studies. They are also indespensable for making conservation priorities (Townsend et al. 2003).

For this study, the flora of vascular plants in two habitats, temporary flooded and unflooded forest, was analysed, partly through general inventory and partly through analyses of plot data. The purpose of the study was to examine the diversity of plants in small forest fragments and to compare the data with the diversity of a bigger patch of natural forest in the same climatic zone.

STUDYAREA

Together with the Andes, the cold northwarding Humboldt and the warm southwarding Panama current affect the diverse climates of western Ecuador (Dodson et al. 1985). The rain season extends from December to May. In the dry season most of the small watercourses dry out and small rivers are reduced to a small stream less then 1 m wide. The area around the coast near Guayaquil is very moist and have high air humidity during the rain season, affected by the Gulf of Guayaquil (Henson 2002). Most rain fall from January through March and the heaviest rains fall a bit further up from the south coast.

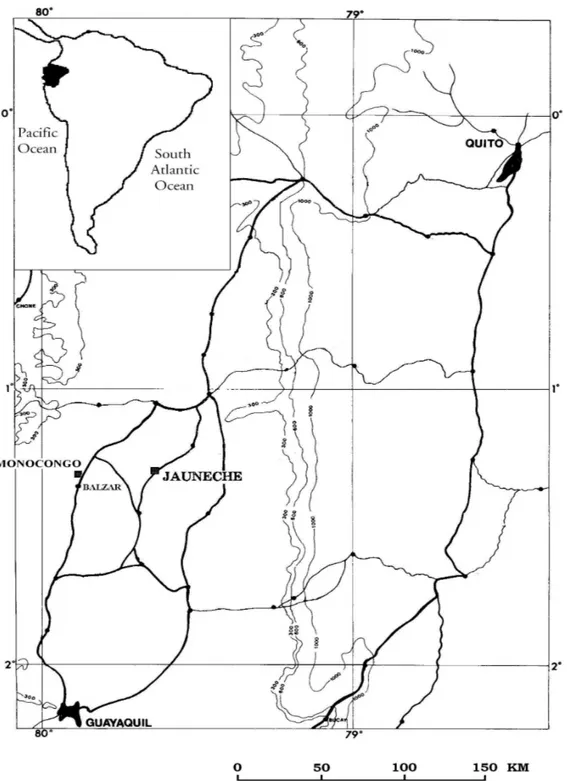

The study areas, Hacienda Monocongo and the Jauneche forest reserve, are situated about 150 km north of Guayaquil (Fig. 1a). The closest village Balzar, is situated 20 km south of

Hacienda Monocongo. The Andes start about 50 km east of Jauneche and the Pacific coast is located at 120 km to the west of the study sites. Both study sites are situated at about 45 m altitude, in hilly terrain with well drained ridges and valleys with small streams and temporary inundated ground. Some hills and ridges have very steep slopes.

At Hda Monocongo, the main stream is Río Mono, a tributary to the larger Río Congo, which crosses in the middle of the Hacienda. The forest fragments of semidecidious moist forest occur around and near these streams and some other smaller watercourses. The vegetation is disturbed but natural, including but few introduced species, and are mostly very dense. Most of the Hacienda is covered by pastures grazed by cattle and teak plantations. The pastures also include many solitary saman trees, a legume (Samanea saman) introduced from Central America (Fig. 1b). The Saman trees provide ample shade and refuges for many wild species of plants and animals. In addition, the pods provide food for the cattle during the dry season. Small flocks of mantled howler monkeys, Alouatta palliata, can be found in the small forest remnants. Smaller herds of red brocket deer, Mazama americana, also inhabit the area and passes through it from the surroundings. Monocongo also house habitats for a variety of squirrels, birds, reptiles and toads.

The nature reserve of Jauneche is a big remnant of semidecidious moist forest but covers a mere 130 ha (Gentry 1986). It is the last undisturbed area with this kind of habitat in the regime, and was unprotected until 1979. During the 1960s and 1970s the inner parts of the forest were untouched, while the owners and local people cut down the outer parts to use the trees for timber. The surrounding properties of the Jauneche reserve consist of plantations of cacao, coffee, corn, cotton and pastures for cattle. There are a variety of wild animals

inhabiting the forest. There is a great share of mammals which consist of bats, squirrels, monkeys, deers, small cats, kinkajous, central american agoutis, pacas, northern tamanduas and tayassuids, which are pig-like animals. There are two species of monkeys, the mantled howler monkey Alouatta palliata and the white-fronted capuchin, Cebus albifrons (Albuja 1992). The monkeys have not been of any interest for hunters during the last years and therefore the populations have remained stable. However, hunting may still affect mammals bound to the ground. There are two species of dear in this area, red brocket deer, Mazama

Fig. 1b. Saman tree, Samanea saman, at Hacienda Monocongo (Photo U.Ridbäck).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Fieldwork was carried out from the beginning of February to the middle of March 2006. Because of the rain season, some parts of the forest fragments where flooded during the period of investigation. All vascular plants except lianas, climbers and epiphytes were registered and collected in plots of 50 m2 (5 x 10 m). The plots were marked with sticks and

placed randomly in two different habitats, temporary flooded and unflooded forest. Within each plot, all individuals were counted and vouchers of each species were collected. Height and stem diameter at breast hight (dbh) were recorded for trees. In multi-stemmed trees all stems were measured separately. In total, I made 12 plots at Hacienda Monocongo, but beacause of floodings only three of these were made in temporary flooded forest. At Jauneche, I made four plots, two in each type of habitat.

In addition to plots, topographic and economic maps of Hacienda Monocongo were used to get an overview of the area and to plot current vegetation types. Excursions along and through the forest fragments gave a view of their size in relation to pastures and plantations. They simplified the inventories, indicating conditions within the fragments and where it was most suitable to make plots. I also made longer excursions to examine the possibility for animals to spread and move through corridors between forest fragments.

The plants were divided into three categories: trees, shrubs and herbs, the last-mentioned group also including ferns. Different reproductive states, flowering, fruitbearing and sterile were recorded. Simpson’s index and Shannon’s index (Magurran 1988) were used to calculate the diversity of the studied life forms at the study sites.

Every plant recieved a temporary name and a number during the fieldwork. One complete duplicate set of the collected material was left at the herbarium of the University of Guayaquil (GUAY). Some unicates were sent to Gotland university on loan and will be returned to Guayaquil when the project is finished. The remaining collections will be deposited at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm (S).

RESULTS

Most of the vegetation consists of pastures and only smaller areas, corresponding to about 15 % of the total area, are used for cultivation of teak at Hacienda Monocongo. Solitary trees and shrubs are occasionally left to grow in the pastures, some building up small islands of partly native species. The fragments of the natural forests are restricted to flat areas close to Río Congo, Río Mono and other smaller watercourses (Fig. 2), as well as to adjacent slopes towards these areas. A rough estimate based on the vegetation map suggest that

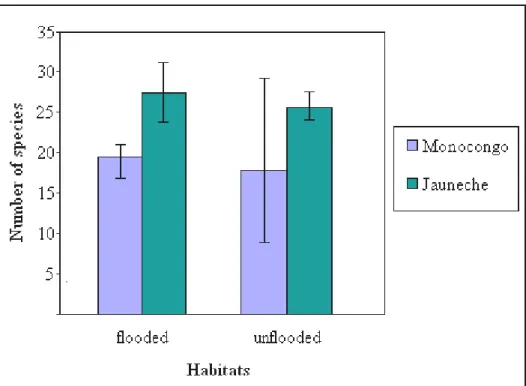

approximately 12 % of Hda Monocongo is covered by variously disturbed, natural forest. The majority of the natural forest fragments on well drained ground grow on slopes, not on ridges, which are either grazed or planted with teak. A satelite image, taken in November 2005 (Google Earth), shows clearly how the forests mainly follow the watercourses (Fig.3). In the neighbouring property, Hda Pan Crudo, some natural forest still exist, but in the other properties surrounding Hda Monocongo, there are nothing left but small islands of forests dominated by domestic species. Also seen on the satelite image are black dots, which probably represent solitary saman trees, the crowns on which easily reaches 50 m in width. On the average the forest of Jauneche has more species of vascular plants than those of Hacienda Monocongo, estimated from the extant samples (Fig. 4). However, one plot at Hda Monocongo had more species than some of the Jauneche plots and one was more or less equal in speciess richness to two of the Jauneche plots. If different life forms are taken into account the abundance of trees and herbs is higher at Jauneche (Tab. 1), whereas the number of shrubs is slighter larger at Hda Monocongo. Both study areas have a higher abundance in the

temporary flooded habitats compared to non-inundated areas, but these differences are not statistically significant. The majority of the trees in all habitats were young individuals, but several larger trees were noted outside of the study plots. All trees shorter than 10 m had a wider stem diameter at Jauneche than in Hda Monocongo, in both habitats, whereas the stem diameter for higher trees were almost the same in both sites, except for one tree reaching 20 m high in the unflooded habitat at Hda Monocongo, which had a wider stem diameter.

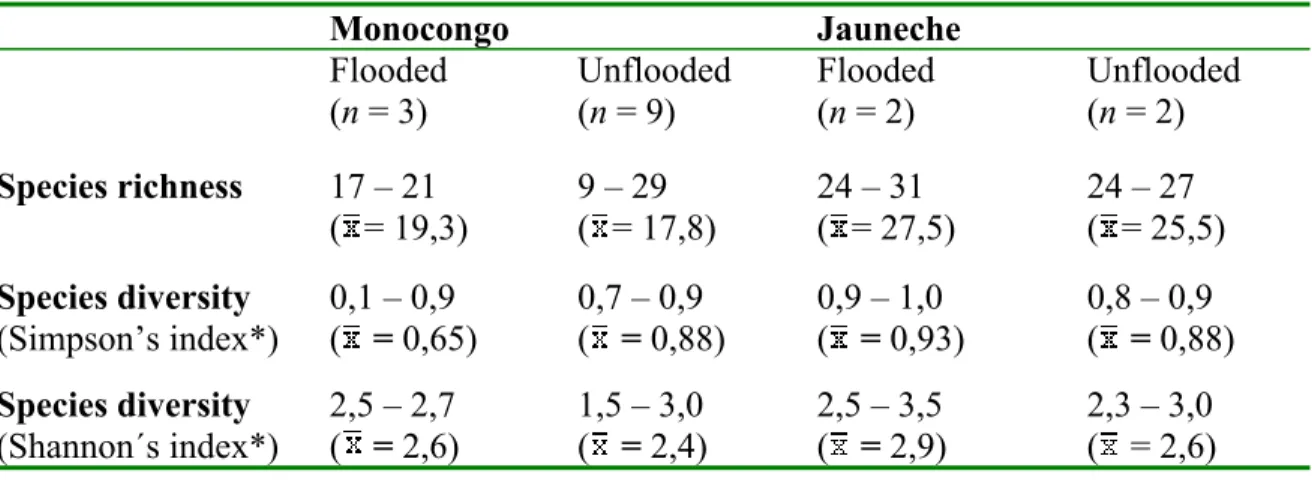

The species diversity at the studied sites follows the same pattern as for species richness in as much as the Jauneche forest had higher values than Hda Monocongo (Tab. 2). This is also true for the relationship between flooded and unflooded forests, the former having generally higher diversity values. However, using Simpson’s Index the unflooded forest at Monocongo was more diverse than the temporary flooded forest at the same locality. There is a prominent higher species turnover in the flooded habitats at Hda Monocongo, whereas the species turnover is almost equal in both habitats in the Jauneche reserve.

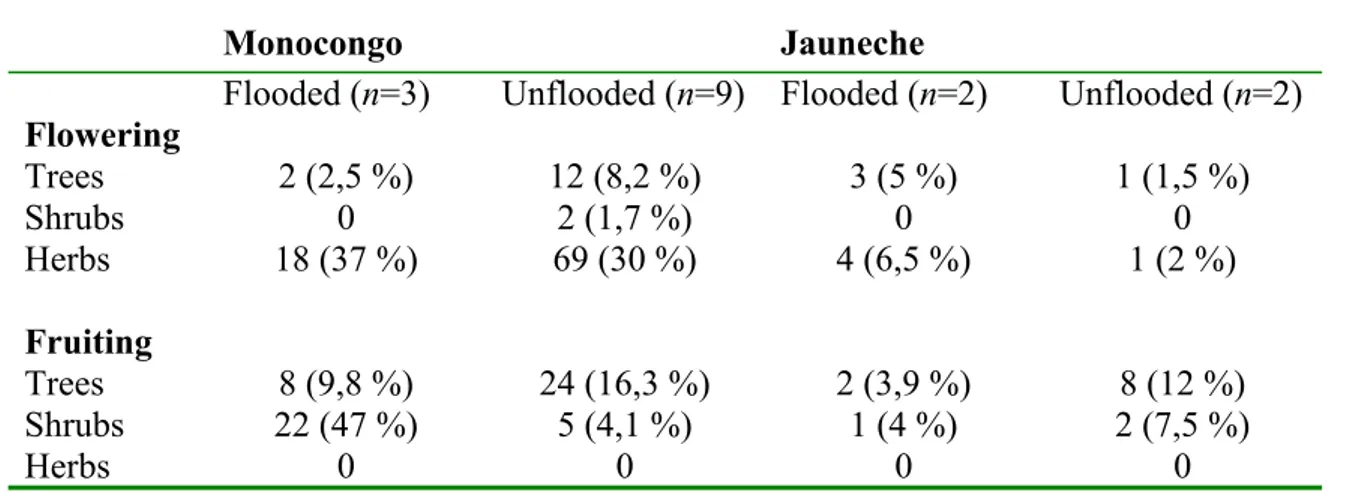

Fruit bearing species consisted of trees and shrubs at both study areas. There were more fruit bearing trees than fruit bearing shrubs. Hda Monocongo had more fruit bearing trees than Jauneche in the flooded habitats. However, in the unflooded habitats the number of fruit bearingtrees was higher at Jauneche.

Fig. 3. Comparing the vegetation map with a satellite image (Google earth).

In both study areas (Tab. 3), most species were sterile at the time of sampling and only a few were flowering or fruit bearing. Hacienda Monocongo had a relatively larger number of flowering species than Jauneche. In the flooded habitats, the flowering species constituted mainly of herbs, such as Heliconia, Calathea, and some species of Piperaceae. There were also a few flowering trees, i.e. Gustavia angustifolia and one species of Meliaceae. In the unflooded habitats, herbs still constituted the majority of the flowering species, mostly

Heliconia and species of Piperaceae. However, unflooded habitats had a larger number of

flowering trees, such as Papaya, and some species of Meliaceae, but had few species of flowering shrubs. The Jauneche reserve only had a few flowering species of herbs and trees, which were almost equal in number in both kinds of habitat. The flowering plants in the flooded habitats consisted of Guadua and Gustavia angustifolia. The flowering herbs

consisted of Calathea. In the unflooded habitats Heliconia and Gustavia angustifolia were the only flowering species.

Table 1. Abundance of vascular plants at Hda Monocongo and Jauneche, in plots of 5x10 m (mean values).

Monocongo Jauneche

Flooded (n=3) Unflooded (n=9) Flooded (n=2) Unflooded (n=2)

Trees 27,3 (20 – 33) 16,4 (7 – 24) 30 (18 – 42) 34 (29 – 39)

Shrubs 15,6 (2 – 39) 13,7 (2 – 50) 12,5 (10 – 15) 13,5 (13 – 14)

Herbs 16,3 (11 – 24) 25,4 (3 – 48) 32 (28 – 36) 25 (0)

Total 59,2 55,5 74,5 72,5

Table 2. Diversity of vascular plants in two habitats at Hda Monocongo and Jauneche.

Monocongo Jauneche Flooded (n = 3) Unflooded (n = 9) Flooded (n = 2) Unflooded (n = 2) Species richness 17 – 21 ( = 19,3) 9 – 29 ( = 17,8) 24 – 31 ( = 27,5) 24 – 27 ( = 25,5) Species diversity (Simpson’s index*) 0,1 – 0,9 ( = 0,65) 0,7 – 0,9 ( = 0,88) 0,9 – 1,0 ( = 0,93) 0,8 – 0,9 ( = 0,88) Species diversity (Shannon´s index*) 2,5 – 2,7 ( = 2,6) 1,5 – 3,0 ( = 2,4) 2,5 – 3,5 ( = 2,9) 2,3 – 3,0 ( = 2,6) * D = å (n/N)2 ** H = – å pi log pi

Table 3. Number of flowering and fruit bearing individuals in plots of 50 m2.

Monocongo Jauneche

Flooded (n=3) Unflooded (n=9) Flooded (n=2) Unflooded (n=2)

Flowering Trees 2 (2,5 %) 12 (8,2 %) 3 (5 %) 1 (1,5 %) Shrubs 0 2 (1,7 %) 0 0 Herbs 18 (37 %) 69 (30 %) 4 (6,5 %) 1 (2 %) Fruiting Trees 8 (9,8 %) 24 (16,3 %) 2 (3,9 %) 8 (12 %) Shrubs 22 (47 %) 5 (4,1 %) 1 (4 %) 2 (7,5 %) Herbs 0 0 0 0 DISCUSSION

At Hacienda Monocongo, pastures have more space than areas used for the cultivation of teak. The remnants of natural forest remains fairly intact, partly because cattle have nothing to graze there. They seem to be in a good state, as judged from overall species richness and diversity. Even if large areas have been affected by human activity, many native plants and animals have spread into the fragments or remained there as relicts.

The larger number of shrubs in Hda Monocongo compared to Jauneche can be a consequense of the more varied landscape at the former site. Some species of shrubs might easily spread into new gaps. When old trees falls, as a natural phenomenon, they leave gaps and may also pull down several nearby trees (Jordan 1986). However, in the edges around the fragments, trees have been removed to increase areas of pastures. This might increase the growth of new sprouts and favour species which require ample light, e.g. many species of flowering herbs and shrubs. This could explain to the larger number of flowering species in Hda Monocongo. Simpson’s index favour the most abundant species and is less sensitive to species richness, while Shannon’s index favour a high number of species (Magurran 1988). The high number of plots that I made at Hda Monocongo, and the high number of individuals that occured in some plots in the unflooded habitat, probably influenced the diversity values I got with Simpson’s index. It should also be taken into account that the sampling was unbalanced, with a much larger sample at Hda Monocongo than at Jauneche, and more samples from unflooded than temporary flooded forests.

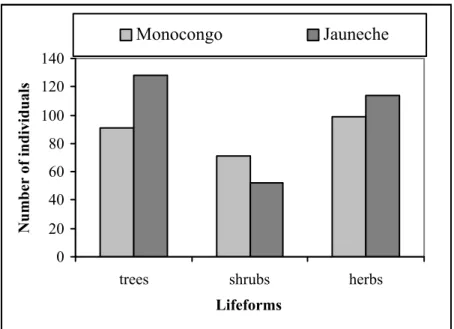

I compared four plots, randomly taken from the data of Hda Monocongo, to compare them with all four plots from Jauneche (Fig. 5). It gives a fair view of the distribution of life forms. Jauneche is a reserve with little disturbance from human activities and is therefore expected to have a high botanical diversity. Because of the larger number of plots in Hda Monocongo I recorded more species there than in Jauneche. But a follow-up study would probably result in the fact of more species in Jauneche. Unfortunately, lack of identifications makes it

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

trees shrubs herbs

Lifeforms

Number of individuals

Monocongo Jauneche

Fig. 5. Comparing the abundance of vascular plants in four randomly chosen plots from Monocongo with all four plots of Jauneche.

In the deepest parts of the fragments at Hda Monocongo, the surrounding pastures can hardly be seen. There are possibilities for wild animals like monkeys, squirrels and birds to move via corridors of vegetation. Howler monkeys are the only wild mammals I noticed. They move within the fragment near Río Mono, where I spotted several individuals, reportadly in two families. They also move cross the border to Hda Pan Crudo, according to the landowners. People living there have reported deer in their properties. Red brocket deer, Mazama

americana, are still common in this area, where they unfortunatly are targets for illegal

hunters. There are long corridors of forests along Río Mono on the side which limit to Hda Pan Crudo, and on each side of Río Congo (Fig. 2, 3). A small string of disturbed forest connects these two areas. The monkeys move primarily in the highest trees and occasionally leave the fragments to move to trees in open areas. While the deers only leave the forest at night. Snakes move almost boundless through the grounds.

Carcasses can easily be found by following vultures, especially black vulture, Coragyps

atratus (Animal diversity web). It is called “la policia” by the local people, because it is

always is gliding over the treetops searching for food, and are often the first ones to feed on carcasses. Turkey-vulture, Cathartes aura, are also very common and can be found in trees close to roads. They usually eat carcasses from traffic accidents. The watercourses and ditches constitute habitats for toads. They sing loudly during the rainy season and sometimes enter gardens following the light from the villages. I have seen lots of them, but no appearance of frogs.

A grazed landcape is more exposed to erosion than natural vegetation. But Hda Moncongo is a well organized farm and the cattle are moved between different parts of the area

Hda Monocongo might be too disturbed for becoming a small nature reserve. The area inhabit many common species, some of them widely distributed in this part of south America.

However, I do not see any bad consequences in letting the natural vegetation expand. It would take a long time though, and some species might not return by themselves. If there are some dominant species, that force weaker species out of the way, than they can be kept in low number with grazing animals, and give room for rare species to recover. Most appropriate are native grazers, like deers and other herbivores, for giving the fragments a natural way to recover. However, cattle and horses may constitue possible substitutes for native grazers under certain conditions.

This study focused on the fact that many plant species suffer a lost of suitable habitats. No complete list of the species that I collected has been compiled. The majority of the species requires a lot of time and knowledge to find their right scientifical names. Some vouchers have not even been placed into families. It is one thing to differ species from one another by their morphological characters, to decide that they are different, and another thing to place them under their scientifical name. In Sweden, like a contrast, all plant species are well known. There is a low number endemic species, but their habitats are not threatened. Some species are uncommon and rare, but they are still well known and in enough number to reproduce themselves.

A study like this one might had been easier to bring through in Sweden than in Ecuador. But the diversity of tropical forests are of more interest and of more value, considering their special ecosystems and the high number of endemism. Even common native species have difficulties in surviving when their habitats change or disappear. Many remaining forests in Ecuador inhabit plant species that can contribute with matter for medical purposes (Gaston 1998). In Sweden hardly any primeval forests exist today and there seems to be more interest in saving culture landscapes. But in Ecuador there is less interest in conserving cultivated landscapes, because it is not a threatened category of habitats.

An incentive to conserve the wilderness could be the creation of hiking tracks, with information about the plant and animal species. This may work particularly well if the

landowners have an interest for nature and have no plans on further exploitation of remaining forest fragments. It can be worth a visit for bypassing travellers. A second step would be to start up ecotourism activities, including all forms of tourism where the interest for nature and culture are primary reasons for the visit (Middleton and Hawkins 1998). It may also produce economic opportunities that make the conservation of natural resources beneficial to local people. The activity can also function as a good example for the surrounding haciendas and change the attitudes for nature. For example, there are no way of taking care of vaste in the countryside, so knowledge about the invironment could contribute to a new system. The remaining wildlife in coastal Ecuador is possible to enjoy within several nature reserves. Guides that are familiar with the areas can often give a better experience for the visitors. There are people that feel insecurity and danger in the wilderness (Emmelin 1997). Some people therefore enjoy nature influenced by humans. But most of the countryside is not available for tourists. A cooperation between Hda Monocongo and Hda Pancrudo could be a good opportunity for saving the little wilderness that is left in this area. Río Congo passes through many haciendas and Pancrudo still has forest fragments left close to the river. However, pastures might be economically more important to the farms then the remaining patches of forest.

Today the level of deforestation has decreased in western Ecuador, but this is primarily a consequence of the fact that hardly any forests remain to cut. In addition, as long as the ground is used for cultivation and grazing, forests will not recover. Disturbed tropical dry forests can return to their original vegetation when left without further disturbance (Josse and Balslev 1994). But if some parts of the pastures in Hda Monocongo could be left without grazing for a longer time, it would be a possibility for the the corridors to increase. Some uncommon tree species are fast growing colonists in disturbed areas. Young plants of this kind of species can be found in the parts where the forest turn into pasture. The wish is to favour the rare and endemic species, to save those that still exists in enough number to survive. The forest fragments had fewer species than an area of the same size in the

undisturbed forest reserve. Though, without further disturbance, the number of species might increase in the fragments to reach an eaqual number of species as in the forest reserve.

A recommendation for a follow-up study would be to identify the plants collected during the field work. This would add qualitative aspects to the work, not least to identify rare and endemic species. It is time-consuming to identify species and to give them their correct scientificial names. I had a lot of help from the local names for some of the plants, which were well known to a lot of people working at Hda Monocongo. However, local names are not always possible to use for finding scientific names and thus the key to the information about them. Some tropical plant families are still quite unknown and therefore hard to recognize. It makes the identification of some species difficult.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Warm thanks to my supervisor Bertil Ståhl, for coming up with the idea of this project and for making it possible to bring it through. I thank Sparbanksstiftelsen Alfas internationella

stipendiefond, for the assignment of a scholarship. Special thanks to Peter and Eva Bohman, for hospitality, good advice and for letting me stay at Hacienda Monocongo. Many thanks to Eusebio Plaza, Franklin Peña, William Loor and Carlos Zalamea at Hda Monocongo. I thank Carmen Bonifaz for extraordinary supervision and help in Ecuador. I also thank Sanna Siitonen for excellent company, comprehension and cooperation during the fieldwork.

REFERENCES

Albuja, L.1992. Mammals of Jauneche. Pages 48-49 in T.A. Parker, III & J.L. Carr (eds.), Status of forest remnants in the cordillera de la costa and adjacent areas of southwestern Ecuador. Conservation international, Washington, DC, U.S.A.

Bibby, C.J. 1998. Selecting areas for conservation. Pages 179-201 in W.J. Sutherland (ed.), Conservation science and action. Blackwell Science Ltd, MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Great Britain.

Dodson, C., Gentry, A.H & Valverde, F.M. 1985. Flora of Jauneche. Tasky editora, Quito, Ecuador.

Emmelin, L. 1997. Turism - Friluftsliv - Naturvård - Ett triangeldrama. Tur R 1997:1. Tryckeribolaget, Östersund, Sweden.

Gaston, K.J. 1998. Biodiversity. Pages 1-19 in W.J. Sutherland (ed.), Conservation science and action. Blackwell Science Ltd, MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Great Britain.

Gentry, A.H. 1995. Diversity and floristic composition of neotropical dry forest. Pages 146-194 in S.H Bullock, H.A. Mooney & E. Medina (eds.), Seasonally dry tropical forests. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Great Britain.

Gentry, A.H. 1993. A field guide to the families and genera of woody plants of Northwest

South America (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru). Conservation International, Washington D.C.,

USA.

Gentry, A.H. 1986. Endemism in tropical versus temperate plant communities. Pages 153-181 in M.E Soulé (ed.), Conservation biology: The science of scarcity and diversity. Sinauer associates, Inc. Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA.

Google Inc. 2005. Google Earth. http://earth.google.com/images_dates.html. Accessed 20th May, 2006.

Henson, R. 2002. The rough guide to weather. Rough Guides Ltd, Shorts Gardens, London, Great Britain.

Jordan, C.F. 1986. Local effects of tropical deforestation. Pages 410-426 in M.E Soulé (ed.), Conservation biology: The science of scarcity and diversity. Sinauer associates Inc., Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA.

Josse, C., Balslev, H. 1994. The composition and structure of a dry semideciduous forest in

western Ecuador. Nordic J. Bot. 14: 425-434.

Magurran, A.E. 1988. Ecological diversity and its measurement. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Middleton, V.T.C. & Hawkins, R. 1998. Sustainable tourism. Martins The Printers Ltd., Berwick-upon-Tweed, Great Britain.

Myers, N. 1986. Tropical deforestation and a mega-extincton spasm. Pages 394-409 in M.E Soulé (ed.), Conservation biology: The science of scarcity and diversity. Sinauer associates Inc., Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA.

Townsend, C.R., Begon, M. & Harper, J.L. 2003. Essentials of ecology, 2nd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford, Great Britain.

University of Michigan 2006. Animal diversity web.

SAMMANFATTNING

Västra Ecuador utgör en yta som motsvarar ungefär en tredjedel av Sverige. Området uppskattas ha mer än 5000 kärlväxter, varav 20 % är endemiska. Området blev tidigt, för nästan 20 år sedan, en känd hotspot för biodiversitet. En hotspot är ett område där stora mängder av endemiska växt– och djurarter genomgår en enorm förlust av habitat. I ett globalt perspektiv är tropiska ekosystem de minst kända, minst studerade och mest hotade. Faktorer som ökar behovet att skydda biodiversiteten i dessa områden är den höga artrikedomen, omfattande endemism och allvarliga förändringar i den naturliga miljön.

Den ursprungliga skogen i västra Ecuador var så gott som orörd fram till början av 1960-talet när det ecuadorianska vägnätet började expandera. Genom det utbredda vägnätet kunde folk ta sig fram till nya områden för att bosätta sig på outnyttjade marker. För att ge plats åt odlingarna skövlades skogarna intensivt under två deccenium. Markerna omvandlades till bananodlingar och plantager där även bomull, majs, kaffe och kakao är viktiga grödor. I dagsläget är det odlingar av banan, teak och oljepalm, samt betesmarker som tar upp stora arealer. Det händer att markägare bevarar bestånd av skog på sina ägor och en förhoppning är att flera skogsfragment tillsammans hyser en stor del av den ursprungliga floran och faunan. Det är troligt att sällsynta arter finns kvar i olika skogsfragment som relikter. Men en stor del arter har försvunnit helt och hållet

Syftet med den här studien var att undersöka den botaniska diversiteten i ett starkt fragmenterat habitat och jämföra med ett större orört skogsområde. Jag har undersökt kärlväxter i två olika typer av habitat, tillfälligt översvämmad skog och icke översvämmad skog. Studieområdena utgjordes av Hacienda Monocongo och skogsreservatet Jauneche, båda belägna ca 150 km norr om Guayaquil. Anderna ligger 50 km öster om Jauneche och

Stillahavskusten 120 km västerut.

På Hda Monocongo används marken i huvudsak till betesmark och teakplantage. De

skogsfragment jag har studerat befinner sig omkring vattendrag. Floden Río Congo går tvärs igenom haciendan och är tätt omsluten av vegetation. Sen finns det en biflod, Río Mono, som också omges av täta skogsfragment. Det kan vara riktigt snårigt och svårframkomligt,

speciellt då terrängen sluttar neråt mot vattendragen. Fältarbetet genomfördes under

regnperioden i februari och mars 2006. Regnperiod infaller normalt under tiden december till maj. Jauneche är den sista orörda säsongstorraskogen i sitt slag och var helt oskyddad under 1960 och 1970-talet. Virke togs från kanterna och en bit in i skogen fram tills 1979, när området blev ett reservat tillhörande universitetet i Guayaquil. Inget mer uttag av virke har skett sedan dess. Omgivningarna är uppodlade med majs och bomull, samt ytor avsedda för bete.

Jag har slumpmässigt lagt ut provrutor om 50 m2 i vardera habitat och samlat alla kärlväxter,

utom lianer, klätterväxter och epifyter. Rutorna märktes ut med pinnar och varje art samlades i en till tre exemplar beroende på tillgången. För träd uppskattade jag även höjden och mätte stamomkrets i brösthöjd. För träd med flera stammar tog jag mått på samtliga stammar. Totalt gjorde jag 12 rutor i Hda Monocongo och 4 stycken i Jauneche. Utöver inventeringen i

Växterna har pressats och torkats på sedvanligt sätt. De pressade exemplaren förvarades i plastpåsar med alkohol ute i fält, eftersom det saknades möjligheter till torkning i fält. Själva torkningen skedde därför i herbariet på Guayaquils universitet. Bestämningen av växter skedde till viss del i fält med hjälp av illustrationer och beskrivningar i Dodson et al. (1985) och Gentry (1993), men det mesta bestämningsarbetet skedde vid Högskolan på Gotland. Bestämningen gick ut på att skilja arter från varann och slå ihop exemplar av samma art. Varje växt fick ett tillfälligt arbetsnamn och ett nummer. En komplett samling av allt material lämnades i Guayaquils universitet. Vissa unikat (växter i ett exemplar) sändes till Gotland som lån och kommer returneras till Guayaquil när projektet avslutats.

Större delen av vegetationen på Hda Monocongo utgörs av betesmark och bara några små ytor används till odling av teak, motsvarande ungefär 15 % av den totala ytan. Enskilda träd och buskar växer ute på betesmarken, vissa bygger upp öar av delvis inhemska arter. De återstående fragmenten ligger på ytor nära Río Congo, Río Mono och andra mindre

vattendrag, såväl som i angränsande sluttningar mot dessa områden. En uppskattning baserad på vegetationskartan föreslår att ca 12 % av Hda Monocongo täcks av störd, naturlig skog. Majoriteten av de naturliga skogarna på väldränerad mark växer i sluttningar, vilka är varken betad eller planterad med teak. En satellit bild från november 2005 visar tydligt hur

skogsfragmenten följer floderna och vattendragen. I den angränsande haciendan Pan Crudo finns det fortfarande lite naturlig skog kvar, men i de andra omgivningarna finns inget kvar, förutom små öar av inhemska arter. På satellitbilden syns även mörka prickar som troligtvis kan vara Samanträd, vilkas kronor lätt får en räckvidd om 50 meter.

Jauneche har i genomsnitt mer arter av kärlväxter än Hda Monocongo i båda habitaten. När det gäller de olika livsformerna är abundansen för träd och örter högre i Jauneche, medan antalet buskar hade en högre andel på Hda Monocongo. Det var en generellt högre abundans i de översvämmade habitaten jämfört med de icke översvämmade på båda studieområdena. Alla träd som var 10 m eller kortare hade bredare stamdiameter i Jauneche än i Monocongo i båda habitattyperna. Artdiversiteten följer samma mönster som artrikedomen då Jauneche har högre värden än Hda Monocongo. Det stämmer även för relationen mellan översvämmad och icke översvämmad skog, där den översvämmade har högre diversitetsvärden. Däremot visade Simson’s index högre diversitet på de icke översvämmade habitaten i Hda Monocongo än de översvämmade på samma lokal. Artomsättningen är framträdande högre i de översvämmade habitaten i Hda Monocongo, medan artomsättningen i Jauneche är likvärdig i båda habitaten. De flesta arterna var sterila på båda studieområdena, men en liten andel blommade eller bar frukt. Hda Monocongo hade en relativt högre andel blommande arter. De översvämmade habitaten hade huvudsakligen blommande örter, men även några träd. I de ickeöversvämmade habitaten var det fortfarande blommande örter som dominerade, men även andelen

blommande träd var högre i antal. Jauneche hade färre blommande individer än Hda Monocongo i båda habitaten. Alla fruktbärande arter utgjordes av träd och buskar på båda studieområdena, där majoriteten bestod av träd. I de översvämmade habitaten hade Hda Monocongo fler fruktbärande träd än Jauneche, medan de icke övesvämmade habitaten i Jauneche hade högre andel fruktbärande träd.

Det höga antalet buskar i Monocongo kan bero på betande boskap. Vissa arter av buskar kan vara lättspridda till nya gap i vegetationen. När gamla träd ger vika och bryts ner blir det stora lediga hål i habitaten. När ett träd faller kan det dessutom dra med sig åtskilliga närstående individer. I kanterna runt fragmenten har träd tagits ned för att utöka betesmarkerna. Det bidrar till mer ljusinsläpp när träd med stora kronor försvinner. Mer solljus släpps in och kan

gynna tillväxten av ljuskrävande arter, bland annat vissa blommande arter av örter och buskar. Det kan vara ett skäl till den högra andelen blommande arter i Monocongo.

Den här studien fokuserade på att många växtarter har drabbats av en förlust på lämpliga habitat. Ingen komplett artlista över de samlade växterna har sammanställts. Majoriteten av växterna kräver tid och kunskap för identifiering på artnivå. Endel har inte ens placerats i sina familjer. Det är en sak att skilja en art från en annan efter morfologiska egenskaper, men en annan sak att placera växter under deras rätta vetenskapliga namn. I Sverige däremot är alla arter välkända. Vissa arter är dock sällsynta, och en liten andel endemiska, men finns ändå i reproduktivt antal.

En studie som denna hade varit enklare att genomföra i Sverige. Men diversiteten i tropiska skogar är av större intresse och värde, med tanke på dess unika ekosystem och endemism. I Sverige finns det knappt någon urskog kvar. Intresset för att bevara kulturlandskap tycks vara större. För botanister finns det inget stort värde i att bevara kulturlandskap i Ecuador. Växter av vetenskapligt värde finns i den vilda natur som återstår.

Fragmenten på Hda Monocongo kan vara utanför intresset att skapa ett reservat, därför att fragmenten är för små och den naturliga skogen störd. Men om vissa delar av betet skulle stängas av under en längre tid så skulle korridorerna kunna expandera. Tropiska torrskogar kan återgå till sitt ursprungliga tillstånd om de lämnas utan vidare störning. Frågan är om det verkligen gynnar de ursprungliga arterna, och om det är tillräckligt många individer kvar för att överleva. En önskan är att det ska gynna de sällsynta och endemiska arterna. Ett sätt att bevara de arter och den lilla vildmark som finns kvar, skulle vara att göra naturstigar för turister. Ett förslag skulle vara en verksamhet inom ekoturism, som gynnar intressen för natur och kultur. Kunskap om resurserna i naturen skulle även gynna lokalbefolkningen i längden. För uppföljande studier skulle jag rekommendera att bestämma växterna som samlades under fältarbetet. Det skulle bidra med kvalitativa aspekter till arbetet, inte minst för att identifiera sällsynta och endemiska arter. Det är tidskrävande att artbestämma växter och endel familjer i det här området vet man fortfarande inte så mycket om. Jag hade mycket hjälp av lokala namn på vissa växter, som var bekanta för många personer som jobbar på Hda Monocongo. Men lokala namn är inte alltid användbara för att hitta de vetenskapliga namnen.