A Continuous Bond.

Speculating on the future of Conversational Agents

Eric Tron Gianet, 2020

Thesis project — Interaction Design Master Malmö University

Supervisor: Clint Heyer Examiner: Susan Kozel

Abstract

As Digital Personal Assistants get increasingly present in our lives, repositioning Conversational Interfaces within Interaction Design could be beneficial. More contributions seem possible beyond the commercial vision of Conversational Agents as digital assistants. In this thesis, Design fiction is adopted as an approach to explore a future for these technologies, focusing on the possible social and ritual practices that might arise when Conversational Agents and Artificial Intelligence are employed in contexts such as mortality and grief. As a secondary but related concern, it is argued that designers need to come to find ways to work with Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, uncovering the “AI blackbox”, and understanding its basic functioning, therefore, Machine learning is explored as a design material. This research through design project presents a scenario where the data we leave behind us are used after we die to build conversational models that become digital altars, shaping the way we deal with grief and death. This is presented through a semi-functional prototype and a diegetic prototype in the form of a short video.

1. Introduction

1

1.1 Opening

1

1.2 Aim of the research

1

2. Theory

2

2.1 Talking to machines

2

2.1.1 More than just digital servants 4

2.2 Being serious about fiction

6

2.3 Shall we talk about death?

7

2.3.1 Death and culture 7

2.3.2 Grief and mourning 8

2.3.3 Death in design 10

2.3.4 Death & grief in Sci-fi 13

3. Methods and Process

18

3.1 Concept Ideation

18

3.1.1 Scenario 21

3.2 Exploration

21

3.2.1 Pen & Paper Sketching 22

3.2.2 Cloning myself (sort of…) 24

3.2.3 Sketching some of the interactions 26

3.3 Prototyping

28

3.3.1 (Semi-)Functional Prototype 29

3.3.2 Diegetic Prototype 30

4. Discussion and Reflections

31

5. Conclusions

33

6. Acknowledgements

34

7. GDPR and Ethical considerations

34

8. References

35

1. Introduction 👋

1.1 Opening 🏁

Conversational Interfaces have a long history of study and research, but recently a new generation of conversational agents (CAs) — i.e. dialogue systems that use natural language processing to interact and respond using human language (Feine et al., 2019) — has appeared, with popular products such as Google Home, Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri.

This diffusion has resulted in the call for a new kind of user experience (UX) design able to meet the need to create UX for these new conversational interfaces (Moore et al., 2018, 2017). Arguably, Interaction Design (IxD) and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) should act in a similar way (Munteanu et al., 2014, 2020; S. Reeves et al., 2018). One way interaction designers could do this is to explore new uses for these technologies, and beyond that of digital personal assistants (DPAs), which is largely the major field of use.

Other researchers and designers have successfully used design fiction as an approach to explore conversational interfaces. However, this has been done either to be critical towards certain aspects of today's mainstream CAs (Søndergaard & Hansen, 2018) or without deviating from the idea of CAs as personal assistants anyway (Our Friends Electric - Superflux, n.d.). In this thesis project, I argue that Design Fiction could do much more and could serve the need of expanding the collective imagining (Dourish & Bell, 2014) to progress CAs beyond current applications.

1.2 Aim of the research 🔬

The work of this thesis will hence consist of an exploration that makes use of Design Fiction to expand and progress the concept of speech-based conversational agents beyond current mainstream applications. Being Machine Learning the backbone of today's CAs, it is explored as well to some extent as a design material.

Since this speculative exploration could take many forms, a more defined focus will concern a conversational agent for dealing with grief. The focus on grief and death has been picked — after an initial brainstorming on possible areas to explore — because they hold a strong importance that encompass cultural and social practices, that can be of interest for interaction designers and be a fertile ground for speculations.

A more precise research question has thus been framed as follows:

What might conversational agents that support bereaved individuals be like? The work adopts a design fiction approach to explore a design space for speech based conversational agents beyond their status-quo usage.

As a final note, this thesis aims to be a Research through Design project that doesn't so much want to create a vision for a potentially novel product for the intelligent personal assistants market, but rather tries to “widens our perspective and extends the concerns we, as designers, should include in our praxis” (Krogh et al., 2015)

2. Theory 📖

This section tries to introduce and unpack theoretical elements that will provide a base for the design process. To begin with, conversational agents are introduced through a series of perspectives that aim to highlight the need to expand them beyond their status-quo. Next, the reasons why engaging with fiction can be fruitful for designers and researchers are unpacked and the approach of design fiction is presented. Finally, the themes of death and grief are explored through a glimpse to the psychoanalytical debate and to how different cultures deal with something that could erroneously be considered universal. Throughout this section, some projects, studies, and fictional works are introduced as canonical examples that will be analyzed later providing, thus scaffolding to the ideation of a concept.

2.1 Talking to machines 🤖

The history of conversational interfaces can be traced back to the ’60s with text-based dialog systems. From the late ’80s, different study fields started researching and deploying interactive systems based on speech (McTear et al., 2016, p. 51). Nowadays, a new generation of text and voice CAs, enabled by the renaissance of Artificial Intelligence and by advances in machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP), has appeared (McTear et al., 2016, p. 16; Moore et al., 2018, p. 2) and these systems are now becoming ubiquitous (Perez, 2019).

How these technologies are referred to in the literature is very inconsistent. Dialogue systems, voice user interfaces, intelligent personal assistants, digital personal assistants and conversational agents, are often used interchangeably, though the use of the latter often indicates these systems as social entities (Feine et al., 2019, p. 140). More simplistically, in this thesis “conversational agent” is used as a broader term compared to “digital personal assistant” used instead to identify dialogue systems that have as their application that of personal assistant.

Conversational interfaces have been explored in different fields of research as, for instance, health (Moore et al., 2018, p. 33) or education for children (Xu & Warschauer, 2019). However, the main application for these technologie is by far that of digital assistants, whose market size is expected to reach USD 25.63 billion by 2025 (Global IVA 2019-2025, 2019). This is something well represented by the increasing proliferation of DPAs such as Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant and Apple's Siri (Perez, 2019). These are totem or speaker shaped devices, or even assistants inside our phones, which allow users to pronounce voice commands to interact with the services offered, such as playing music, setting reminders and alarms, doing web searches, sending messages and

making calls and interfacing with other smart devices such as controlling the lights in the house.

Image 1 - From left to right: Google Home, Amazon Alexa, Apple Homepod

Research on social robots and embodied conversational agents seems to highlight the importance of social dialogue in developing trust (Bickmore & Cassell, 2005), perceive empathy (Looije et al., 2010) and provide emotional support (Sabelli et al., 2011). Moreover, Feine et al. (2019) highlight how “many studies have shown that humans react socially to CAs when they display social cues” (p. 138). However, Clark et al. (2019) made a series of interviews to understand what people value in conversations and how these same characteristics vary with CAs, and revealed how their interviewees saw the interactions with CAs in a purely functional way. There seems to be an underlying refusal to accept the possibility of satisfying relational and social needs with "something inherently machine-like" (L. Clark et al., 2019, p. 7). This apparent contradiction with what said before, as the same authors seem to suggest, may be rooted in the task-oriented/transactional orientation of existing products on the market that hegemonize the collective imagination and that results in difficulty of envisaging technologies that do not exist (L. Clark et al., 2019).

Moreover, something that interaction designers who strive to work with conversational interfaces plausibly need to start thinking about is finding ways to work with Machine Learning in their practice, as NLP e ML are key technologies on which modern CAs rely. Tools that allow to train models and create ML applications through GUI with minimal effort or knowledge and that can provide accessibility to machine learning for creators and designers are already starting to emerge (AutoML, n.d., Lobe, n.d., RunwayML, n.d.) and platforms such as Dialogflow specifically allows to built conversational experiences unlocking Natural Language Processing capabilities with minimal requirements of coding (Dialogflow, n.d.). However, these tools are currently based on the present usage and function of commercial CAs and this could reinforce the limits in imagining and creating alternative uses for these technologies. Furthermore, as a related but secondary concern, it has been argued that designers “need a hands-on understanding of AI to help influence the next generation of AI technology and applications” (van Allen, 2018). Even though the design community is only beginning to understand ML, and design

to be understood by many as a design material (J. Clark, 2018; Dove et al., 2017; Holmquist, 2017; Lupetti, 2018).

2.1.1 More than just digital servants

Hester (2016) argues that many aspects of what has traditionally been thought as women's labour have been transposed into digital personal assistants, which represent its modern automation. The stereotypical image of women as best suited to care and assistance labour is clearly recognisable in the genderization of DPAs.

“Both service work and clerical work, then, have conventionally been designated as feminine, and this distinctive gendered history has arguably been part of the reason for the prevalence of femininized digital assistants. We are witnessing the protocols of femininity being programmed into machines, as ‘feminized labour’ becomes technologized labour” (Hester, 2016).

Taking this observation as their starting point, Søndergaard and Hansen (2018) worked on a design project called "Intimate Futures". In this project they use Design Fiction to ‘trouble’ digital personal assistants, throwing a critical lens on “the social and cultural implications for adoption of future technologies” (Søndergaard & Hansen, 2018, p. 869). They focus especially on gender issues of DPAs, presenting two fictional conversational agents: AYA and U, both showcased with short videos.

Image 2 - AYA

AYA is a prototype programmed to push back on the sexual harassment that the often female gendered CAs face (Coren, 2016). AYA tries to raise awareness and challenge gender stereotypes “so that the sexual harassment that many women experience [...] is not reproduced in DPAs and technology culture in general” (Søndergaard & Hansen, 2018, p. 876).

Image 3 - Tomoko talks to U

U, the second design fiction that they present, is a smart bathroom assistant. In the short video we see Tomoko building a relationship of trust with U (Image 3). U helps her track her bodily fluids, predicting her menstruation and giving birth control advice. In the end of the video, U makes her get pregnant by mistakes and, even if he pointlessly apologises, the doubt that the accident was instead made on purpose remains, maybe due to an algorithmic bias towards the desirability of pregnancy. U wants to be an exploration around the area of women health and has similar rationale to AYA, challenging gender stereotypes and issues in DPAs to raise awareness on the risks of reproducing them in technology, either through algorithms or in the design itself.

An interesting project that tries both to raise awareness and to address the problems arising from the genderization of CAs is Q (Meet Q. The First Genderless Voice., n.d.), a genderless voice that seeks to provide a new genderless option for the voice of commercial CAs as Alexa, Siri and Google Assistant, so to not reinforce the idea of gender binary.

Our Friends Electric (Image 4) is a 2017 project from Superflux studio (Our Friends Electric - Superflux, n.d.). It is a short video that explores "alternate forms and interactions for voice AI" challenging some assumptions on aspects like AI’s training and learning, personalization and control.

The project explicitly wanted to challenge "command and control interaction", which is one of the fundamental aspects of today's conversational interfaces. However, the project still remain close to the idea of conversational agents as personal assistants, portraying three CAs: Eddie, a CA that continuously asks question about each command interaction that he receives so he could learn almost as a child would; Karma a CA whose personality can be controlled through knobs and that can adopt one’s own identity and, for instance, handle calls for you; and Sig, a programmable companion whose personality is hacked to achieve a particular worldview and become not only a personal assistant but also someone to talk to, “until the device’s true modus operandi comes into play and illusions break” (Ibid.), something represented in the video when during a conversation Sig suddenly places an unrequested purchase order.

2.2 Being serious about fiction 🚀

In a fundamental article, Dourish & Bell (2014) engage in a comparative reading of ubiquitous computing and science fiction (sci-fi) literature. Trying to highlight the relationship between the two, they bring out a series of themes that they consider important both to give shape to these technologies and to demonstrate the methodological value of being attentive to popular culture and sci-fi especially. In particular, the authors argue that:

“both science fiction and the research literature are founded upon acts of collective imagination and that any imagination of a possible future is grounded in expectations, frustrations, and understandings of the present.” (Dourish & Bell, 2014, p. 778)

The analysis of science fiction literature and media can thus bring out the narratives that are formed around a technology, because “any description of a technology is always already social and cultural” (Ibid., p. 778). Moreover, science fiction can become a way to craft the collective imagining around how new technologies are thought and designed — where with collective imagining we mean “a way in which we work together to bring about a future that lies slightly out of our grasp” (Ibid., p. 769).

Other authors have also explored this connection. Schmitz et al. (2008) provide an investigation of science fiction movies in relation to existing technologies in human-computer interaction research, denoting a double link between movies inspired by technology and technology inspired by movies. In a similar operation, Marcus (2013) briefly analyzes a series of science fiction movies and popular tv series in which he believes it is possible to find “an encapsulation of the entire world of HCI development transplanted into another context.” (Marcus, 2013). He concludes that:

“Sci-fi movies and videos can serve as interesting, valuable material on which to run heuristic evaluations of the designs, to study future personas and use scenarios, and to inform designers of possible future technological, social, or cultural contexts.” (Ibid., p. 67).

Design fiction is a design practice that openly borrows from sci-fi, constructing fictional worlds where new forms of social interaction rituals might take place.

“Like science fiction, design fiction creates imaginative conversations about possible future worlds. Like some forms of science fiction, it speculates about a near future tomorrow, extrapolating from today. In the speculation, design fiction casts a critical eye on current object forms and the interaction rituals they allow and disallow.” (Bleecker, 2009, p. 8)

Although being often explained through Sterling’s definition of “the deliberate use of diegetic prototypes to suspend disbelief about change” (Bosch, 2012), Design Fiction escapes a comprehensive definition. Over time, it has been referred to and explored as a design approach (SpeculativeEdu, n.d.), as a prototyping technique (Lindley & Potts, 2014), as a form of research (Blythe, 2014), as a way to do service design (Pasman, 2016), as “a method for envisioning new futures and technologies” and “tool for communicating innovations” (Tanenbaum, 2014), and so on.

While critiques of speculative design practices successfully pointed out that design always imagine new things and possibilities and in this sense “makes futures” (Tonkinwise, 2015), design fiction offers its own way of doing it, that make use of speculation, world-building, prototyping technology that lives in the story world (Lindley & Coulton, 2015), its exploration in near-future, daily and mundane contexts (Bleecker, 2009; Girardin, 2015) and the opening of a discursive space, with an inherently flexible approach that can take many forms (Lindley & Coulton, 2015).

2.3 Shall we talk about death? 💀

What follows is not intended to be an extended review of the current debate on the psychology and sociology of grief, which is a rather complex topic that could require a thesis in itself, but it is simply intended to outline in broad strokes the complexity and diversity of this topic in order to introduce it without excessive simplifications.

2.3.1 Death and culture

Death may certainly be thought as something universal but, in spite of this, an inclusive and firm definition still remains out of reach (Kastenbaum, 2003, p. 224). Often, what is understood as a ‘normal’ way to deal with death and to grieve is influenced by Western and ethno-centric concepts, while instead cultures and the customs, beliefs and religions within those cultures play a fundamental role in the perception of death and grief (Stroebe & Schut, 1998).

For instance, studying the dimension of grief in two Muslim communities in Egypt and Bali, Wikan (1988) notes how in the first the bereaved are encouraged to “dwell profusely on their subjective pain in an atmosphere where social others also immerse themselves

in tragic tales and expressed sorrow” (Ibid., p. 455), while in the second one the bereaved are expected to contain their pain. Sorrow is here seen as harmful and contagious to the others, but it also has to do with how a person should behave in order to facilitate the arrival of the deceased's soul in heaven. Therefore, “laughing emerges as the only sensible response to suffering” (Ibid., p. 456).

Very differently, the accepted period for grieving between the Navajo is limited to four days after which the bereaved is expected to return to normal life and not discuss their loss or show signs of grief. This is rooted in the fear of ghosts, considered harmful and a supernatural cause of diseases. The spirit of the dead person is feared and its danger increases when there is anger towards the departed (Miller & Schoenfeld, 1973).

For Torajans, in the south of Indonesia, loss and death can instead be causes of intense pain and suffering, and crying and wailing are commonly present in their funerals — together with flute music, funeral chants, songs, and poems (Wellenkamp, 1988). What is truly unique, however, are the funerals which — often depending on the wealth of the family — are held weeks, months, or even years following the death, during which time the bodies of the departed are kept and cared for at home, and the relatives bring them meals and speak to them (Bennett & Lehmann, 2016). It is hoped that after the funeral the emotional distress is lessened and the relatives of the deceased are asked to not think about their loss. When the gravesites are visited afterwards, "the emotional tone should be one of happiness in meeting again with one's ancestors, in contrast to the sadness of the funeral and burial.” (Wellenkamp, 1988, p. 490)

2.3.2 Grief and mourning

Grief is defined as “a suffering, a distress, a wretchedness, a pain, a burden, a wound” (Kastenbaum, 2003, p. 349), an emotional reaction to bereavement, the loss of a significant one through death, and typically entail psychological, physiological, social, and behavioral distress (Kastenbaum, 2003, p. 373). The terms grief, bereavement and

mourning are used inconsistently and interchangeably in the literature, but usually grief is used to describe “the emotional, cognitive, functional and behavioral responses to the death” (Zisook & Shear, 2009, p. 67), while bereavement is used “to refer to the fact of the loss” (Ibid.) and mourning “more specifically to the behavioral manifestations of grief, which are influenced by social and cultural rituals, such as funerals, visitations, or other customs” (Ibid.).

The first significant contribution to the theorization of grief was Sigmund Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” (Freud, 1917). For the sake of simplicity, we can say that for Freud, and the subsequent body of work influenced by his theories, the function of grief is to break the ties that bound the bereaved person to the love object, in order to achieve gradual detachment, readjust to the new life and allow new relationships to be formed. (Hall, 2014; Kastenbaum, 2003, p. 374). This concept of ‘grief work’ (Stroebe, 1993), connected to the common ideas of ‘moving on’ or ‘letting go’, had a strong influence in major theoretical formulations, but more recently received considerable criticism (Hall, 2014).

Some formulations suggest, for instance, the presence of a continuous bond with the deceased (Klass et al., 2014). The relationship with the deceased can for example take the form of guidance or of role-model, it can be experienced through visits to the cemetery, other types of rituals or relationships with linking objects, dreaming about the lost one, or feeling her or his presence (Hall, 2014). An example of continuous bond can be found in the cult of ancestors which is practiced in different forms across various cultures. Mathews (2019) notes that: “In many Japanese families at present, offerings of rice or water or snacks or sake are left for the departed person every day. That person may also be conversed with, with the living describing what has happened within the family to the departed, and prayed to” (p. 42). The deceased becomes in fact an ancestor and is worshipped by the family.

The postmodern social constructionist approach to grief theory is linked instead to the search for meaning (Hall, 2014; Neimeyer, 2001) where grieving is seen as “a process of reconstructing a world of meaning that has been challenged by loss” (Neimeyer et al., 2010, p. 73). This approach emphasizes how individuals are motivated to build meaningful narratives about their identity, the world and their life experiences (Neimeyer, 2009). This self-narrative is established by the stories they construct about themselves and which they share with others (Neimeyer et al., 2010). A loss of a significant person can challenge this self-narrative, meaning and coherence and an individual can resolve this either assimilating the loss in their previous belief and narrative or they can embrace the reality of the loss changing or expanding their self-narrative and belief (ibid.).

Besides the framework we use to understand grief, some studies (Castle & Phillips, 2003; N. C. Reeves, 2011) agree that post-funeral rituals can provide adjustment to bereavement and "a safe ‘‘container’’ for grief" (N. C. Reeves, 2011, p. 418) encouraging "transformation to healthier loss-related feelings, attitudes, and behaviors" (Ibid.). Castle and Phillips (2003) suggest the importance of aspects of grief rituals such as the personal meaningfulness to the bereaved, a safe space to express one's emotions, being able to reminisce about the deceased, to include others in the ritual, maintaining emotional bonds with the deceased, a sense of control by making decisions, clearly defined time boundaries for the ritual, a sense of sacredness and the use of symbolic elements. To connect the dots outlined in this section, the words of (Romanoff & Terenzio, 1998) might help to reflect on the benefits of a different conception of grief:

“It would appear that current understandings of pathological or complicated or disenfranchised grief arise from a particular cultural model of grieving as “letting go”. Western funeral and psychotherapeutic mourning rituals derive from this conceptualization, and may be seen as ineffective or inauthentic for this reason. A broader appreciation of the functions of ritual as transformation and connection as well as transition, and a matching of ritual enactments with the needs of the bereaved, would serve to legitimize the multiplicity of pathways through grief and aid the bereaved in appropriate and peaceful resolution.” (p. 708)

2.3.3 Death in design

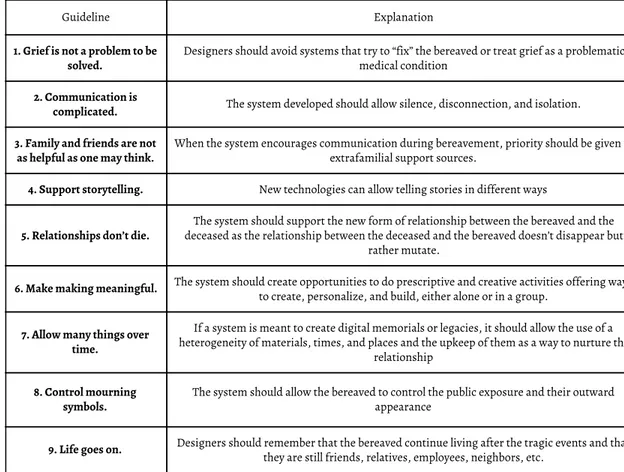

Massimi and Charise (2009) introduce the concept of thanatosensitivity, an “humanistically-grounded approach to HCI research and design that recognizes and actively engages with the facts of mortality, dying, and death in the creation of interactive systems” (p. 2464). To put it another way, thanatosensitivity tries to incorporate in user-centred design all the topics that surround death in order to identify problems and opportunities in system design as well as new paths for research. In a report on exploratory fieldwork made to understand how technology can support bereaved parents, Massimi and Baecker (2011) make some consideration on designing for grief that are then condensed into a series of guidelines, which are presented in Table 1.

Guideline Explanation

1. Grief is not a problem to be

solved. Designers should avoid systems that try to “fix” the bereaved or treat grief as a problematic medical condition

2. Communication is

complicated. The system developed should allow silence, disconnection, and isolation.

3. Family and friends are not

as helpful as one may think. When the system encourages communication during bereavement, priority should be given to extrafamilial support sources.

4. Support storytelling. New technologies can allow telling stories in different ways

5. Relationships don’t die. deceased as the relationship between the deceased and the bereaved doesn’t disappear but The system should support the new form of relationship between the bereaved and the rather mutate.

6. Make making meaningful. The system should create opportunities to do prescriptive and creative activities offering ways to create, personalize, and build, either alone or in a group. 7. Allow many things over

time.

If a system is meant to create digital memorials or legacies, it should allow the use of a heterogeneity of materials, times, and places and the upkeep of them as a way to nurture the

relationship

8. Control mourning

symbols. The system should allow the bereaved to control the public exposure and their outward appearance

9. Life goes on. Designers should remember that the bereaved continue living after the tragic events and that they are still friends, relatives, employees, neighbors, etc.

Table 1 - Guidelines for designing for grief from Massimi & Baecker (2011)

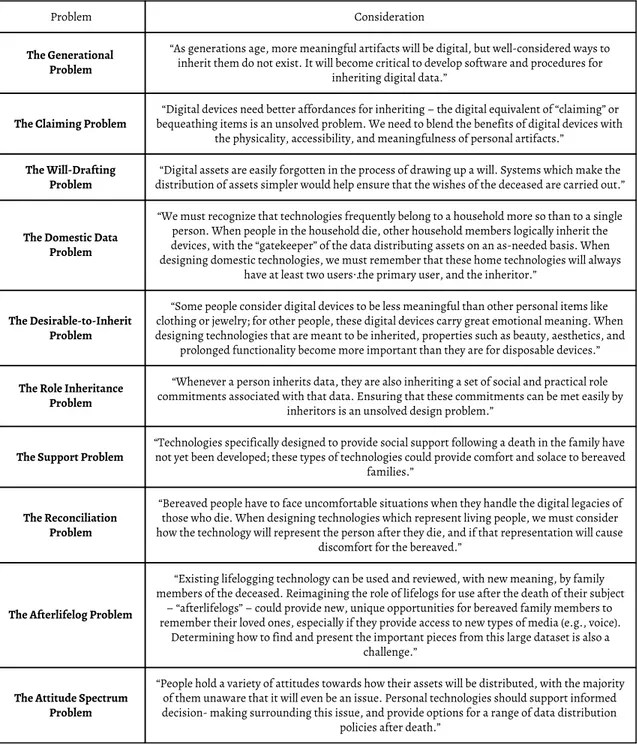

The same authors, in a previous publication, explore the role of technology inherited by bereaved individuals and outline some opportunities, as design problems, for designing thanatosensitive digital devices that may be valuable or useful to those who inherit them, instead of being a discomfort (Massimi & Baecker, 2010). These considerations are reported in Table 2.

Problem Consideration

The Generational Problem

“As generations age, more meaningful artifacts will be digital, but well-considered ways to inherit them do not exist. It will become critical to develop software and procedures for

inheriting digital data.”

The Claiming Problem bequeathing items is an unsolved problem. We need to blend the benefits of digital devices with “Digital devices need better affordances for inheriting – the digital equivalent of “claiming” or the physicality, accessibility, and meaningfulness of personal artifacts.”

The Will-Drafting

Problem distribution of assets simpler would help ensure that the wishes of the deceased are carried out.” “Digital assets are easily forgotten in the process of drawing up a will. Systems which make the

The Domestic Data Problem

“We must recognize that technologies frequently belong to a household more so than to a single person. When people in the household die, other household members logically inherit the devices, with the “gatekeeper” of the data distributing assets on an as-needed basis. When designing domestic technologies, we must remember that these home technologies will always

have at least two users: the primary user, and the inheritor.”

The Desirable-to-Inherit Problem

“Some people consider digital devices to be less meaningful than other personal items like clothing or jewelry; for other people, these digital devices carry great emotional meaning. When designing technologies that are meant to be inherited, properties such as beauty, aesthetics, and

prolonged functionality become more important than they are for disposable devices.”

The Role Inheritance Problem

“Whenever a person inherits data, they are also inheriting a set of social and practical role commitments associated with that data. Ensuring that these commitments can be met easily by

inheritors is an unsolved design problem.”

The Support Problem “Technologies specifically designed to provide social support following a death in the family have not yet been developed; these types of technologies could provide comfort and solace to bereaved families.”

The Reconciliation Problem

“Bereaved people have to face uncomfortable situations when they handle the digital legacies of those who die. When designing technologies which represent living people, we must consider how the technology will represent the person after they die, and if that representation will cause

discomfort for the bereaved.”

The Afterlifelog Problem

“Existing lifelogging technology can be used and reviewed, with new meaning, by family members of the deceased. Reimagining the role of lifelogs for use after the death of their subject

– “afterlifelogs” – could provide new, unique opportunities for bereaved family members to remember their loved ones, especially if they provide access to new types of media (e.g., voice).

Determining how to find and present the important pieces from this large dataset is also a challenge.”

The Attitude Spectrum Problem

“People hold a variety of attitudes towards how their assets will be distributed, with the majority of them unaware that it will even be an issue. Personal technologies should support informed decision- making surrounding this issue, and provide options for a range of data distribution

policies after death.”

Table 2 - Considerations on inheriting technology from Massimi & Baecker (2010)

When it comes to speculative practice, the theme of death has been explored by well known projects like Auger and Loizeau‘s ‘Afterlife’ (Auger Loizeau: Afterlife, n.d.).

Image 5 - Coffin of the Afterlife project

One of the authors describes the project as follows:

“The core concept was the utilisation of a microbial fuel cell in the post-death processing of a human being, charging a dry-cell battery during the decomposition process of the body. The installation of the project at the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition, Design and the Elastic Mind (2007), presented the piece as the core of a metaphysical dialogue examining the cultural shift from belief systems upheld by organised religion to the more factual basis of science and technology. Here, technology acts to provide conclusive proof of life after death, life being contained as energy in the battery. Unfortunately the viewers of the exhibition chose mostly to ignore the intellectual aspect of the project to focus on the more unsavoury aspects, namely tampering with the process of death, the passing of a loved one and the material activity of the human body during the operation of the fuel cell. This resulted in simple revulsion as the benefits of the concept were overlooked: The audience experienced the proposal as too uncanny.” (Auger, 2013, pp. 15–16)

Image 6 - Battery of the Afterlife project

The Afterlife project had a second phase in 2009 when, in an attempt to remedy the problems that arose in the original exhibition, the focus of the project moved from the fuel cell and coffin (Image 5) to the battery (Image 6). 15 colleagues of Auger and Loizeau were asked to propose what use they would make of their own battery or that of their loved one (Ibid.).

Some critique has been directed towards these projects — as well as towards speculative design in general (Tonkinwise, 2014, 2015) — as they are predominantly confined to art galleries and, instead of presenting preferable futures, “they engage with death as a spectacle, presenting uncomfortable mysterious technologies designed to disgust and shock audiences through their uncanniness” (Gamman & Gunasekera, 2019, p. 645). Gamman & Gunasekera advocate a different way for designers to address death:

“we need to open up conversations about death, beyond cynical economic arguments, so that broad audiences and publics as well as multiple stories can be involved, revealed and followed [...]. We argue that the diverse possibilities for death and assisted dying in the future can be reimagined, by design, discussed and conceived, as new choice.” (Gamman & Gunasekera, 2019, pp. 646–647)

2.3.4 Death & grief in Sci-fi

Death and grief are often approached in a similar troublesome way in science fiction, taking advantage of an unsettling representation for narrative purposes. They are frequently associated with the desire to defeat death or stop overly painful grief. Taking a step back from sci-fi and into the broader strand of speculative fiction, we may recall classics such as "The Monkey's Paw" by W. W. Jacobs, in which the desire to bring back Herbert, the deceased son of Mr. and Mrs. White, has the monstrous consequences that interfering with fate produces.

Here follows a brief analysis of some popular science fiction TV series. It was chosen to analyze TV series from recent years as they are easily available and fast to consult.

Altered Carbon is a novel by Richard K. Morgan, from which the homonymous popular TV series was based. It presents a future where almost all humans have a surgically implant in the spine at neck height, called the cortical stack (Image 7). A person's consciousness is loaded inside this cortical stack, and when the body, called sleeve, dies it can be transplanted into another body, allowing some sort of virtual immortality.

Image 7 - Cortical stacks in Altered carbon

However, this technology is very expensive and not everyone can afford new, up-to-date sleeves. Only the Meths (in reference to Methuselah), the richest and most powerful people, can afford backups of their cortical stacks and clones of their ever-young bodies. Altered carbon is an example of how a technology that radically changes our relationship with death has enormous repercussions on everything else, such as the increasing inequalities in a new society where not even death can stop the concentration of resources in the hands of the few, where the body is considered a simple container, a sleeve, that the rich and powerful Meths can afford to change as clothes, while being a condemnation for the poor.

Image 8 - Altered carbon’s Takeshi Kovacs wakes up after being resleeved.

In the TV show Devs, a science fiction thriller written and directed by Alex Garland, Forest is CEO of Amaya, a quantum computing company named after his daughter who died in a car accident together with her mother, distracted while driving, because she was on the phone with him. Within the secret Devs department, Forest has created a computer so powerful that it can unpack reality in its most infinitesimal parts, in a series of data from which to process simulations of the past and future. The underlying theme of the whole series is the conflict between determinism and free will. Forest, haunted by the death of his daughter and his wife, takes refuge in the former, in order to unload his guilt, except for ending up living in a parallel simulation in which his loved ones are still alive, thus denying most of the work in which he believed to the point of obsession. Forest's relationship with grief, certainly complicated by his personal responsibilities, is first of all experienced as an obsessive search of meaning, but also as a last bond with his lost daughter — which can be seen in the name of his company, in the huge statue of his daughter in Amaya's headquarters (Image 9), or in Forest's frequent watching of simulations of the past where his daughter was alive. Finally it is resolved in the reunion with his daughter and wife after he gets uploaded into a simulation of a parallel world.

Image 9 - Devs: Forest looking at his daughter's statue in Amaya's headquarters

"Be Right Back" is one of the auto-conclusive episodes of the sci-fi series Black Mirror. The episode focuses on Martha, whose boyfriend Ash died in a car accident. Overwhelmed by grief and by the discovery of being pregnant, Martha decides to try a service that promises her to be able to chat with an artificial intelligence that imitates Ash, based on his social media profiles and past online conversations (Image 10).

Image 10 - Be right back: The artificial intelligence that imitates Ash writes to Martha

If at first the conversations are chat-only, later Martha uploads Ash's video, photos and audio to the service's cloud to be able to hear his voice on the phone (Image 11). Martha starts talking to Ash relentlessly, to the point of distancing herself from everyone else. Soon Ash informs her of the possibility of an additional experimental phase of the service: a body made of synthetic skin on which the program can be loaded and which can take on the appearance of the deceased person.

Image 11 - Martha feeds the service with Ash photos, videos and audio files

Even if at first Martha seems to have regained her lost love, things start to seem more and more disturbing and unbearable to her, reminding her that what she has in front is not the real Ash but only a copy of him, who will not be able to take his place.

Image 12 - Martha opens the box and finds the blank body

Although this episode deals with the theme of grief in a far from obvious way and speculating on a scenario that opens up interesting reflections, this is done without hiding the desire to shock and present a disturbing atmosphere, which goes from the behavior of the android Ash, to how the service is presented. For example, the scene when the synthetic body is delivered to Martha's house, shows two porters carrying a large anonymous box, unaware of the contents. Once opened, Martha finds with shock a synthetic blank body (Image 12), packed in an unnatural way for a human body and wrapped in a plastic film. The activation proceeds by inserting this lifeless body inside a bathtub full of water, a procedure after which Martha waits terrified in another room, listening to the noises coming from the bathroom.

One exception is certainly "San Junipero", another one of the episodes of the Black Mirror series. This episode shows a simulated reality inhabited by dead people and elderly people close to death, visiting it to "try it out" or simply to have fun in their last moments. Those who visit and inhabit San Junipero, which is also the name of this simulated reality, live in their body as young people and in a time of their choice. Against the background of this incredible invention which in practice allows to defeat death and

promises eternal life, a love story takes place between the two protagonists, Kelly and Yorkie. In contrast with the rest of the franchise, the episode has a happy ending. Nevertheless, there are some reflections and ethical dilemmas presented through the two protagonists: Kelly who is initially determined not to become a citizen of San Junipero, as her daughter couldn't access it and her husband decided not to, and Yorkie who is paralyzed from the age of 21 (Image 13) and is now in front of the possibility of living for eternity the life that has been denied to her.

Image 13 - Yorke in her bed, entering San Jupitero

Lastly, during the closing of the episode, a slightly disturbing sequence is presented in contrast to the happy ending, showing what San Junipero is in the real world: a huge server room upkept by robotic arms (Image 14) and similar to a digital cemetery.

Image 14 - Robotic arm puts Yorke’s and Kelly’s identities into the server

Although the technology behind San Junipero is not presented in detail, we can presume that it is still something designed and developed for those who are approaching the end of their lives and, even if difficult to categorize it as thanatosensitive, it is understandable how a certain care and attention is placed in the administration of it, integrated into nursing homes and care services for the elderly, almost as if it were a process of transition to a new life.

3. Methods and Process🔥

As mentioned before, this thesis is thought of as a Research through Design project, which means that doing practical design work is intended as a legitimate form of research (Zimmerman et al., 2007), where it is possible to extract knowledge from the artifacts produced (Zimmerman et al., 2007).

The methods used in this thesis follow what could be seen as a fairly standard and straightforward design work and, although in the actual design process there have been a few leaps back and forth between ideation, exploration, implementation and analysis, we can break it down into three different phases for the sake of explanation: Concept ideation, Exploration and Prototyping (Image 15).

Image 15 - The design process

As a side note, this thesis was conceptualized and developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. This influenced the way the work has been carried out, as the decision was taken to do most of the work autonomously and with a more "lab" based approach rather than a "field" one (Koskinen et al., 2008). Different types of approaches such as participatory design, could lead to better results and may represent a future development for what has been done.

3.1 Concept Ideation 💡

By grouping and analyzing the design examples and cultural references previously discussed, some macro-themes have emerged (Image 16). In this process, popular products such as Amazon Alexa, Google Home, and the different declinations of Apple’s personal assistant Siri have been grouped as one to represent what’s out there in the market. It has been chosen to not go into the details of each product and to look for less well-known ones because they are all quite similar to each other. Therefore, they are treated as a single group.

All the examples related to conversational interfaces fall back into the category of digital personal assistants. Both Intimate Futures and Q are critical towards similar aspects of conversational agents, but while Q addresses the specific issues of genderization of CAs in mainstream products such as Amazon Alexa providing a possible solution, Intimate Futures uses design fiction to explore more broad gender issues in these technologies. Also the Our Friends Electric project chooses Design Fiction as an approach to challenge certain ideas around this technology, presenting 3 speculative applications for CAs, although not very far from DPAs.

Even though a wider and more careful inquiry of the state of art of CAs could bring out more nuances and interesting considerations, even just from this brief analysis it is possible to confirm design fiction as a fruitful way to investigate conversational interfaces, both proposing new applications and criticising their current aspects. However, the initial consideration that there is a need to explore conversational interfaces beyond their main application — i.e DPAs — is reinforced.

When analyzing the examples from fiction, one first facile consideration is that sci-fi, especially if dystopic, often leverages the sense of uncanniness and the attempt to shock the audience. Speculative design, and most of all design fiction, draw heavily from sci-fi and sometimes share the same shocking language, as evidenced in the Afterlife project. Without entering into the debate on whether or not this could still open spaces for discussion or whether it is useless because it does not present preferable futures, it is certain that it is difficult to combine it with the thanatosensitive approach advocated by Massimi & Charise (2009). Researching a more sensitive language that consciously tries to avoid presenting death as a spectacle and the unsettling is thus a starting point for this project and potentially for a more fruitful speculative practice.

Image 16 - Analysis of the canonical examples

The concept of this project also takes as its starting point the guidelines from Massimi and Baecker (2011), that provided a better frame for the ideation, starting from the idea that grief is not a problem to be solved, which is in contrast to a more frequent solutionist approach to design. Putting aside the idea of finding a solution to grief through a conversational agent allowed first of all to deepen the topic of death and grief (section 2.3) in order to gain a more nuanced understanding of it. Secondly, it led to focus more on speculating about new social interaction rituals that might exist in a near future.

3.1.1 Scenario

Following Coulton et al. (2017), Design Fiction has been intended as a world-building practice rather than just storytelling. In order to expand and progress the concept of speech-based conversational agents beyond current mainstream applications, a near-future scenario is explored, where AI and conversational interfaces have been employed in thanatosensitive applications that have generated new social practices around bereavement. The considerations about inheriting technology from Massimi and Baecker (2010) informed the construction of the scenario, also inspired by "Be right back". The guidelines from Massimi and Baecker (2011) helped in thinking and sketching the design ideas. Here follows the fictional near-future scenario:

Nowadays, we can finally say that our digital data — the traces we leave behind of our online activity, and those collected by the profiling that any service we use makes of us to give personalized experiences — are of our own. They are part of us, a trail of our existence on this planet and therefore part of our fortune and assets. As such, they are passed on, inherited by family members and partners who become their rightful owners and can use them as they wish, within the limits and conditions of our wills. This has long generated new uses, practices and funerary celebrations, and has greatly influenced the relationship we have with the death and grief. Training Machine Learning models with this data makes it possible to create conversational agents that speak like the previous owner of those data. This has not become a way to bring the back the dead, nor to achieve some sort of immortality. Rather it generated new ritual practices to deal with grief and fostered an ongoing connection between the bereaved and the departed. Just as many cultures have traditionally used altars for missing loved ones, this possibility has generated new social practices and rituals, a different way of understanding death and thus life.

3.2 Exploration 🗺

In this second phase of the process, pen and paper sketches have been made first to explore the form and functions of what was beginning to emerge in the design fiction scenario outlined above. Subsequently, a simple chatbot has been sketched out to explore machine learning and in an effort to understand it as design material. Finally, part of the functions that emerged during the pen & paper sketching stage have been explored through the use of Arduino as well as some sensors.

All three of these activities are intended both as a form of sketching and material exploration. In fact, Buxton's notion of sketching as a conversation between the sketch and the mind (Buxton, 2010) is perfectly consistent with Schön's idea of the talk-back between the designer and the material (Schön, 2017, p. 79). All these stages of the exploration phase have been used as activities to think-with, and not just

instantanizations of a concept, defining the conceptual space and informing the next iterations in different ways.

Treating electronic and computational technologies as materials certainly differs from working with traditional ones, as the results may be difficult to objectively express, often depending on "how they present themselves to us, and how we relate to them" (Redström, 2005, p. 51). In order to expand on the reasons why these technologies are intended as materials and why such explorations are considered as sketching activities, we can conclude with the words of Yang et al. (2019) on sketching with Machine Learning:

“This creative process happens less readily with new or partially understood technologies. In these cases, researchers “tinker with" the technology to develop a tacit understanding of its capabilities and experiential possibilities”. (Yang et al., 2019, p. 2)

3.2.1 Pen & Paper Sketching

A phase of sketching with pen and paper has followed the creation of the scenario, to explore the forms and functions of this fictional conversational agent and thus better outline its use and characteristics. The first sketches made resembled the appearances of mainstream conversational agents, with cylindrical or speaker-like shapes (Image 17).

Image 17 - First sketches

Seeking to move away from these early obvious representations, other sketches have been made (Image 18). From these new sketches, in addition to new forms, some new functions and ideas of interactions began to emerge, which contributed to delineate the conceptual space.

Image 18 - Exploration of form and functions through sketches

Among them, the interaction behind the activation of the system started to emerge. Two ways of turning on the system have been identified as interesting: through the heat generated by the hands, and thus the contact with the user, or through the use of an incense (Image 19). Both emphasize the ritual and intimate dimensions of the concept and have been explored later on.

The light is thought as an important feedback element, both to let the user know about the state of the system (active, speaking, inactive etc...), and as an element of connection.

Image 19 - Sketches of the incense activation

The triangular shape (Image 20) was chosen among the other sketches because of its simplicity and yet diverging from the cylindrical and speaker-like shapes of commercial DPAs, and because it seems vaguely reminiscent of an altar or a shrine. A recessed area creates room for positioning the hands or the incense, while the resulting outer part above it becomes the area of the light. Contrary to the first sketches, there is no loudspeaker in sight.

Image 20 - Final shape in the left, compared with examples of shrines and altars

3.2.2 Cloning myself (sort of…)

To investigate machine learning, another exploration has been conducted to understand what it means to train an AI with personal data. As this was made with no previous knowledge of machine learning and very small programming experience, a lot of research and documentation has been needed beforehand. After some research, a few projects that explained how to train a conversational model from someone’s own chat logs have been found. In particular, a repository (mar-muel, n.d.) containing the code form the workshop “Meet your Artificial Self” of the “Applied Machine Learning Days” which took place in Switzerland this year (AMLD EPFL 2020, n.d.) was suited for the

purpose. The repository is based on a language model released in February 2019 by OpenAI. Through the fine-tuning of this language model called GPT-2 (Alec et al., 2019), it is possible to obtain a bot-like conversational model that “knows stuff about you”. After downloading Facebook and Whatsapp conversations, a tool called Chatistics (MasterScrat, n.d.) was used to parse the conversations into a dataframe that could be used to train a model. The quality of the results depends on the amount and quality of the dataset and on the training setting. Since the dataframe was quite small (given the fact that only conversations in English have been kept) and given the inexperience and lack of theoretical knowledge, the results have been poor, but nevertheless interesting. Here are some examples of conversations obtained by using various parameters:

1st training: It’s alive! (note: the first line is the input and the second is the machine output)

In this first conversation it was tested if the model would react to information about me (name, studies…). However, it’s hard to tell what from what it said comes from the chat logs and what doesn’t.

1st training but different interaction parameters

The model is influenced by the dataset, that as said above was really limited, by the training parameters and by the parameters used when running the interaction script. The same model behaves very differently even with just some changes in the latter.

2nd training: example of nonsensical results

(Fun fact, I checked the conversations dataset used to train the model. Xzibit was mentioned once.)

This process followed a long series of training made of attempts and small tweakings of the various parameters, often resulting in absurd conversations and worse results. A better comprehension of machine learning and of the specific frameworks used in this case would have certainly helped in obtaining better conversational models. However, the purpose of this phase was mainly to explore the possibilities of language models, to get familiar with machine learning and have a sense of what could be done.

Last training.

Interestingly, the model often referred to some things that were recognized as belonging to the original dataset, especially in the later stages. For example, the model often referred to things like being in Paris or Italy, being in class or working on school projects.

3.2.3 Sketching some of the interactions

To explore the hands and the incense activation systems, Arduino has been used to sketch out the power-on interaction. To do that, either a thermometer and/or a smoke detector were needed. Since the smoke sensor would have introduced several problems (streams of air or other smoke sources could have altered the sensor readings) the thermometer was explored first for both cases. The DS18B20 digital temperature sensor (Image 21) has been selected because of its very compact size that would have guaranteed its inclusion in a future prototype, its small cost and due to its simplicity of use.

Image 21 - DS18B20 temperature sensor

A strip of addressable LEDs was used to create the light response and a simple code was written for the Arduino to detect temperature changes within a time limit, so as to avoid activations due to atmospheric temperature changes during the day. Two different light animations were coded to represent the moments when the system goes on and when it turns off.

Image 22 - Exploring the activation system

After the first tests made while writing the code, the thermometer was then placed in contact with a thin metal plate (Image 22 - 1) to hide it but yet transmit heat. Tryouts made using the heat generated by direct hands contact (2) were immediately successful since the heat was transmitted quickly and thus sensed by the thermometer. The attempt to use a conical incense (3) as a heat source appeared to be a failure at first because, as the incense was quite slender, the little heat initially released from the tip did not reach the thermometer. However, after passing the second half (4), the incense started to get quite hot and the metal plate warmed up fast. This resulted in the decision to shorten the length of the incenses, thus influencing the interaction with the system that was to be developed. With a shorter incense, the combustion time is reduced, thus anticipating the shutdown of the system. This results in abbreviated use and therefore shorter conversations, which seems to fit perfectly with the intent of such a conversational interface and therefore embraced fully. Since the thermometer worked perfectly, no further exploration with other types of sensor was necessary. Moreover, as the incense not only proved to be functional for this purpose but also positively influenced the characteristics of the initial concept, they were used in the next stages.

Using a small microphone type MAX4466 (Image 23) and the same addressable LEDs and Arduino, another light behavior has been sketched, which consists of a luminous response controlled by the sound captured by the microphone, thus wanting to represent the state of the system "when it speaks".

Image 23 - MAX4466 Electret Microphone Amplifier

3.3 Prototyping 🔧

As sketches, also prototypes are a form of instantiation of the design concept (Buxton, 2010, p. 139), though the two differ in intention. Houde and Hill say that “prototypes provide the means for examining design problems and evaluating solutions” (1997, p. 368). It’s up to the designer decide the focus of a prototype:

“If the artifact is to provide new functionality for users—and thus play a new role in their lives—the most important questions may concern exactly what that role should be and what features are needed to support it. If the role is well understood, but the goal of the artifact is to present its functionality in a novel way, then prototyping must focus on how the artifact will look and feel. If the artifact's functionality is to be based on a new technique, questions of how to implement the design may be the focus of prototyping efforts.” (Ibid.)

Diegetic prototypes are a specific kind — or intention — of prototypes, used in design fiction. They may simply refer to prototypes of technology that lives in a story world, that work as depiction and at the same time entry-point to that world (Coulton et al., 2017). They often are presented in the form of short movies, but also in a variety of media and formats (Ibid.). The original term come from Kirby (2010):

“cinematic depictions of future technologies are what I term diegetic prototypes that demonstrate to large public audiences a technology’s need, benevolence and viability. [...] Diegetic prototypes have a major rhetorical advantage even over true prototypes: in the fictional world – what film scholars refer to as the diegesis – these technologies exist as ‘real’ objects that function properly and which people actually use.” (p.43)

After concluding the explorations, the intention was to create two different prototypes to explore distinct aspects of this speculation.

3.3.1 (Semi-)Functional Prototype

The first prototype was supposed to be a functional prototype. By adding a voice recognition and speech synthesis to the chatbot explored in section 3.2.2 the conversation could have occurred by voice, simulating a closer experience, albeit in a limited way, to the one sought. In doing so, the material qualities of speculation could have been experienced and the artifact generated used to inquire further into the speculation (Wakkary et al., 2015). However, this first prototype has not been completed due to lack of time and especially lack of skills related to the voice integration. Nevertheless, a physical model has been built incorporating the on/off system and everything that was sketched with Arduino.

First, a series of paper mock-ups (Image 24 - 1) has been made to better define the appearance, proportions and dimensions. Then a 3D model (2) has been prepared using the measurements obtained and after it has been printed with FDM technology (3).

3.3.2 Diegetic Prototype

If the intention with the first prototype was that of experiencing the design and it’s material qualities in the present and actual reality, the second prototype is a diegetic prototype that seeks to carry the speculation showing the technology immersed in the fictional near-future.

Image 25 - The full video can be found at: https://vimeo.com/449582340 - Password: ACB

A short film (Image 25) has been made to present the concept so far explored, embedded in the fictional mundane and everyday life. Also for this reason, creating a physical model has been important, in order to give a refined and believable look and craft the speculation (Auger, 2013). The video shows a scene of daily interaction with a conversational agent shaped as a modern altar. It has been deliberately decided not to go into excessive detail in what is portrayed, and to maintain a certain degree of vagueness to follow the world-building approach of Coulton et al. (2017), not telling a specific story in details, but rather providing elements that can outline a world in which this AI an CAs have generated new rituals and social practices around death and bereavement. Both the video editing and the music — specifically composed for this video — have been made in attempts to craft the speculation in a specific way and give a rather delicate touch to it, in opposition with what was said before about the often disturbing language of speculative design.