Leading in Stressful

Environments

Bachelor Project

Thesis Within: Business Administration Number of Credits: 15 credits

Programme of Study: International Management

Author: Joakim Bredberg, Ezabella Kwok and Gustav Nordberg

Acknowledgements

Before commencing this research, we wish to formally acknowledge certain persons who

fundamentally where involved in our process and development of this bachelor thesis.

First, we would like to explicitly express our gratitude to our tutor Michal Zawadzki for the support and guidance during the entire research process. The constructive feedback that he provided enabled us to develop this research into more advanced levels. Second, we also wish to thank the co-operating seminar groups at Jönköping University for their recommendations. All groups gave us plentiful and extraordinary useful feedback in the various seminars, from the initial pitch to the first official draft of this thesis. Last but not least, the contribution of the respondents who granted us the qualitative interviews which became the basis of our entire research must not be neglected. We are grateful to you all for having provided us with precious insights in the fields of leadership and working in the football environment.

We thank you all!

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Leading in Stressful Environments

Authors: Joakim Bredberg, Ezabella Kwok and Gustav Nordberg

Tutor: Michal Zawadzki

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Leadership, Stress, Stressful Environments, Coping with Stress, Football,

Relationships

Abstract

Background: Football accounts for 43% of the sports market share, more than any other

single sport. The pressure and stress associated with being a sports leader indicate that the football coaches encounter and work with occupational stress more regularly than corporate leaders. Hence, football coaches appear to be highly appropriate to acquire insights from. Although there is extensive literature on stress, the research on football coaches is lacking.

Purpose: The purpose of this research is to deepen the understanding of leading in a

stressful environment. The aim is to acquire useful insights into various existing stress coping methods that reduce the negative impact that stress may have on contemporary leaders.

Method: The interpretivism paradigm is appliedto this research as well as an abductive approach to grounded theory. The research is based on a single case study where primary data is acquired through semi-structured interviews with three football coaches and three players. Furthermore, the thematic analysis approach is applied when analyzing the data in order to draw applicable conclusions.

Results: The empirical findings suggest that there is a relationship between football

coaches and their players. Furthermore, leading in the football environment is vastly shaped by this, however: industry specific stressors also play a significant role, such as management turnover. Several stress coping methods are identified in this study. The most prominent propel mentality, focus on progress and love for the sport, referred to as mental disengagement. This study is useful since it contributes with valuable insights of how leaders can efficiently cope with stress and lead in stressful environments.

Table of Content

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Purpose ... 2 1.3 Research Questions ... 32

Frame of Reference ... 3

2.1 Traditional Views on Leadership ... 4

2.2 Contemporary Views on Leadership ... 4

2.3 Leadership in Football ... 6

2.4 Leading in Stressful Environments ... 6

2.5 Work Stress ... 7

2.5.1 Consequences from Work Stress ... 8

2.6 Teamwork ... 9

2.6.1 Team Dynamics ... 11

2.6.2 Team Leadership ... 11

2.6.3 Moral Disengagement in Sports ... 12

2.6.4 The Dark Side of Teamwork ... 13

2.7 Different Types of Pressure ... 14

2.8 Coping with Stress ... 15

2.8.1 The Impact of Mental Disengagement ... 16

2.8.2 Physical Activity and Stress ... 17

2.9 Summary ... 17

3

Methodology ... 18

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 18 3.2 Research Design ... 19 3.3 Data Collection ... 20 3.4 Interview Design ... 21 3.5 Sample Selection ... 22 3.6 Data Analysis ... 244

Empirical Findings ... 26

4.1 Views on Leadership ... 264.2 Views on Stress and Pressure ... 29

5

Analysis... 34

5.1 The Relationship Between Coaches and Players ... 35

5.2 Challenges of Leading in Stressful Environments ... 38

5.3 Coping with Stress ... 40

6

Conclusion ... 43

7

Discussion ... 43

7.1 Discussion ... 44 7.2 Practical Implications ... 46 7.3 Theoretical Contributions ... 46 7.4 Research Quality ... 47 7.5 Ethical Considerations ... 47References ... 51

Appendix 1: Interview Questions for Coaches ... 67

Appendix 2: Interview Questions for Players ... 68

1 Introduction

This section introduces the reader to essential background on the football environment and presents what the coming literature review will elaborate on. On the basis of this introduction, the reader will become aware of the reasoning for the choice of this research field and the purpose of our thesis.

1.1 Background

Sports, including football, are the number one leisure activity for many people around the globe, gathering large numbers of spectators. Football is considered the most popular single sport in the world where the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), the international governing body of football, has 211 national member associations (Giulianotti, 2012). The industry has continued to grow, both counting supporters and turnovers, putting more pressure on the efficient use of resources and strategic management (Hamil & Chadwick, 2010). In 2018, revenues bypassed 90 billion

USD in 2017, including entry tickets, media and marketing activities (Statista, 2018).

Football accounts for 43% of the sports market share, which is more than any other sport (Deloitte, 2017). Due to the vast reach of the sport and the enormous pressure put on football coaches, there are evident indications that sport leaders in this field work with organizational stress management on a far more regular basis than business leaders since fatigue and lack of fitness are the largest contributors to football players’ stress (Brink, Visscher, Coutts & Lemmink, 2012).

This thesis scrutinizes football coaches’ methods of coping with stress in highly competitive leagues in northern Europe. Regardless if it is Premier League, Serie A,

Bundesliga or the Finnish highest league Veikkausliiga is investigated, the sport is

fundamentally built on its supporters, the players and its leaders (Bond & Addesa, 2019; Poolton, Siu & Masters, 2011). Generally speaking, all teams consist of coaches and players, however, a good coach deliberately takes care of the players and attempts to positively impact a player’s overall well-being (Mason, 2006). For instance, the coach should attempt to decrease any negative emotions associated with being a newcomer and always provide assistance when needed to ensure that members of the team thrive. Leaders' behavior is proven to be significant in the followers’ acceptance of the leader

and the performance of the followers (Malik, Aziz & Hassan, 2014; Wu, 2012). Therefore, this thesis will use the terms followers and followership repeatedly in the football environment without a dehumanizing interpretation. Instead, followers are defined as those who are influenced by the leader in the process to achieve common goals (Chatwani, 2018).

The leadership field has been researched for centuries and has different meanings for various people. It can be viewed as the ability to influence and increase a sense of power among the followers (Follett, 1942), as well as the process of working towards common goals (Chatwani, 2018; Silva, 2016) and taking care of people (Gabriel, 2015). The leadership style can have a significant impact on the performance and the experienced workload. An increasing number of people are experiencing work stress which negatively impacts an individual’s well-being as well as work performance (Kopp, Stauder, Purebl, Janszky & Skrabski, 2008). Working in the football industry can be extremely stressful due to the industry’s size. The existing literature on stress is substantial; however, the literature on football coaches’ management of stress appears to be lacking. The leader, or in this case the coach, experiences a significant amount of pressure and stress even on days off (Williams, 2020). Furthermore, football coaches manage organizational stress more frequently than business leaders (Brink et al., 2012). Therefore, football appears to be a highly relevant sport to acquire insights from on this topic.

1.2 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to deepen the understanding of leading in a stressful environment, such as the football industry. The aim is to derive useful insights that could improve strategies of dealing with stress levels and thus potentially enhance performance by understanding how football coaches lead and cope with stress in a stressful environment. It is evident that leadership has different interpretations and implications depending on scale, environment and executioners, but is prevalent enough to render significant advantages if understood correctly. Accordingly, a vast comprehension of leading in stressful environments enables individuals to become better practitioners. However, since the vast majority of leadership research has been conducted in the educational sector, the extent to which these theories can be transferred across industries remains unclear (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2017).

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is not to define concrete methods that make leadership more efficient but rather to contribute to the existing understanding of leading in stressful environments. Numerous methods and literature exist on how athletes can handle stress in order to improve performance and overall well-being (Bartlett & Bussey, 2013; Ivancevic, Greenberg & Greenberg, 2015; Kellmann, 2010). Nevertheless, the literature on how coaches in various sports can manage stress is lacking, which implies a gap in research. Additionally, there is a need to develop leaders’ guides on operational stress to support team members as well as their families (Adler, Cawkill, van Den Berg, Arvers, Puente, Cuvelier & Adler, 2008). This paper attempts to fill that gap.

1.3 Research Question

The existing literature includes research on the development of the view on leadership and stress management, however, the way football coaches cope with stress is yet to be investigated. This research can identify the challenges associated with leading in a stressful environment and thus facilitate the way people cope with stress. Since the aim of this paper is to contribute and deepen the understanding of leadership in stressful environments, the research question is as follows:

“What are the challenges of leading in the football environment and how do football coaches cope with stress?”

The first part of the question attempts to render a clearer image of the stress that football coaches deal with. For instance, what triggers stress and what type of stress that has the largest impact on the coach’s ability to perform as he aspires to. The second part of the question is the cardinal component of this paper. By understanding concrete ways that football coaches cope with stress, the insights may improve the existing methods used to cope with various levels of stress, which could diminish experienced stress levels for these leaders. Needless to say, this requires the intuition derived from the first section. Consequently, our frame of reference will bring up versatile literature within both areas.

2 Frame of Reference

Since this paper aims to scrutinize stress coping for leaders in stressful environments, the following pages will present existing theories used to analyze and answer our stated

purpose. The whole literature review concerns football context, although, parallels will continuously be drawn to other contexts for more useful insights on stress as a phenomenon and its implications. We begin with describing leadership roles and environments and later emphasize on work stress, including its triggers and outcomes. Furthermore, the focus will be on the connection stress has with teamwork, physical activity and workplace environments.

2.1 Traditional Views on Leadership

As long as leadership enhances understanding, empathy and mutual respect, it is worth studying, regardless whether the research concerns a football club or a small profit driven enterprise. Individuals receive constant pressure from others, business managers, peers, politicians and religious leaders, in attempts to turn them into followers. Studying leadership enables us to rigorously examine our own leadership as well as that of others, in a more reasoned way (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2017). Leadership has been widely contested for thousands of years. The ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius argued it is about serving people (Brooks & Brooks, 1998) and Plato focused more on wisdom (Takala, 1998). Even in the 19th century, leadership was still viewed as a personality trait (Carlyle, 1993).

It was not until after WWII that the viewpoints changed towards leadership being a process influencing action towards a predetermined goal (Stogdill, 1950). This sparked the revolution of goal setting and determination. Since then, philosophers have defined leadership as; interpersonal influence (Tannenbaum, Weschler & Massarik, 1961), use of force (Volckmann, 2012), interaction process (Bass, 1990), influence relationship (Rost, 1991), capacity (Bennis & Townsend, 1995), shared power (Sveiby, 2011) and the feature of having followers (Drucker, 1996). After this ongoing debate, modern philosophers appear to have mostly agreed that leadership is far more than a personality trait.

2.2 Contemporary Views on Leadership

A difference between Confucius’ ancient idea and present-day views is that the context and followers in modern times have a significantly greater role than before. This has a noteworthy impact on this bachelor thesis, since leadership tools in an environment

Poolton et al., 2011; Learmonth & Morrell, 2017). Needless to say, the concept of followers implies different meanings in different contexts (e.g. sport fans, learning disciplines and political supporters) and, in a broader sense, even include employees (Collinson, 2017). Realizing that followers’ attitude towards the manager changes leadership per definition, complexity arises in comparisons. However, it also means that the concept of “team” is significant, which will be further discussed. The concept of leadership is becoming more and more aligned with business and management studies, differing only in the sense that leadership regards “doing the right things” instead of simply “doing things right” (Bennis & Nanus, 1985).

Contemporary definitions concern the process between a leader and their followers during endeavors to acquire shared goals (Silva, 2016) and the dynamic process intersecting followership, leaders and moving the group towards collective goals (Chatwani, 2018). However, contemporary perspectives on leaders and leadership differ (Cotter-Lockard, 2018). In recent years, critical perspectives have emerged that challenge the hegemonic view, these include distributed leadership, team leadership and self-managed teams (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2017). Distributed leadership refers to a fluid concept, moving between numerous parts of an organization to combine efforts towards a desirable outcome (Gosling, Bolden & Petrov, 2009; Gronn, 2002). Similarly, shared leadership (Pearce & Conger, 2003), collaborative leadership (Kramer & Crespy, 2011), participative leadership (Vroom & Yago, 1998), leaderful practice (Raelin, 2011), collective leadership (Friedrich, Vessey, Schuelke, Ruark & Mumford, 2009), co-leadership (Heenan & Bennis, 2000), and democratic co-leadership (Gastil, 1997) may be included within the concept of distributed leadership, questioning the conventional perception of leadership as a possession of an individual (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2017). This paper does not scrutinize these concepts since the topic is stress for leaders, instead, we conclude that there are plenty of varieties of distributed leadership nowadays which suggests that leadership is commonly held by more than one single individual, making contemporary views on leadership significantly different from traditional views. In a case from a Swedish suburb with significantly high criminal activity, the inclusion in a new football club not only halved the crime rates, it changed the attitudes of the players for the better as well (Carlson, 2007). Thus, proper leadership has remarkable potential to impact individual’s well-being outside of the workplace (Nichols, 2007). A recent study

in Malaysia, for instance, indicates that democratic leadership approaches are more favored by players (Yusoff & Muhamad, 2018). However, even in football, a leader has to exist in order to distribute the leadership, regardless of how well distributed the leadership in the organization becomes (Hatcher, 2005).

2.3 Leadership in Football

In football, there are three different managers: chairman, sports director and coach. A chairman intentionally serves as the central power source within the club and usually sits longer than both a club’s sports director and a business CEO. In Scandinavia, the chairman typically holds his position for around four years, whilst the average sport director or CEO sits half that time. A coach, which is the main focus in this thesis, only sits for one year on average (Gammelsaeter, 2012), which could be an indication of the enormous pressure coaches have to cope with. In some cases, the coach also acts as the sports director in a club. However, in Sweden, the two positions are represented by two different individuals. As mentioned previously, this paper focuses on the second case, where the coach and the sports director are two individuals. Creativity and motivation skills from a leader are difficult to examine (Söderman, 2013). In response to this, Söderman (2013) developed a model consisting of four areas in which a coach can be properly assessed from: Atmosphere, Match, Coaching and Management.

Management and coaching occur to a much larger extent between the matches than during the matches. Coaching is led by the head coach but not solely executed by that person. Players, assistants and other members who seek to develop tactics, playing styles and team spirit are also coaching. Additionally, management is based on strategy, acquisitions, leadership development and marketing activities, only to mention a few examples (Söderman, 2013). Apart from a manager's reputation, team composition is evaluated to have a significant relationship with sporting success, and thus ought to be a core area for the football coach to focus on between matches (Teichmann, 2007). Hence, football leadership is complex and different tasks can lead to different levels of stress on the leader.

2.4 Leading in Stressful Environments

Although workplace stressors are prevalent in several different environments, certain industries are larger victims to this phenomenon. For instance, manufacturing, military

and health services exhibit significant amounts of operational stress (Deming, 2000; Adler, et al., 2008; Rimmer, 2018), aside from sport environments. In the production industry insecurity regarding instructions, lack of knowledge about one’s tasks and absence of necessary tools are three factors largely contributing to elevated stress levels (Deming, 2000). Furthermore, through the NATO research panel, 16 participating countries responded in a survey that stress-related mental health problems are common for military leaders. The findings also suggested that stress not only impacts the military unit members but also their families. This implies that stress may have a tendency to multiply and spread across relations (Adler, et al., 2008).

Similarly, working as a nurse is often associated with a high level of occupational stress, high work demands as well as significant numbers of burnouts and mental health problems. Stress represents the main suspected cause for this. Stressors prevalent in the work environment varies depending on cultures and health care systems. Nevertheless, there are various factors that contribute to burnouts (Chen, Guo, Lin, Lee, Hu, Ho & Shiao, 2020), such as, ergonomic hazards from carrying heavy objects or lifting patients which subsequently may lead to lower back pain (Yip, 2001) and the inability of taking leaves due to no substitutes (Mizuno‐Lewis & Mcallister, 2008).

Leadership in healthcare has traditionally had a more hierarchical and top down approach, however, the need for more efficient leadership approaches has been recognized and various initiatives have been implemented (Martin, Beech, Macintosh & Bushfield, 2015; Oliver, 2006; Adler, et al., 2008; Wicks, 2006). Some of these initiatives are consistent updates in codes of conducts and policy moves, which are proven to sometimes cause the opposite effect, uncertainty (Holden & Roberts, 2004). Hence, the shift of focus from operations to leadership may be unsuccessful from a stress perspective and this process may provoke a darker side of teamwork, not frequently discussed (Sinclair, 1992).

2.5 Work Stress

Due to the fact that the working conditions can considerably influence people's well-being, it is useful to highlight this factor. Fortunately, there is extensive literature on work stress where the impact it has on mental health is clearly established. The emergence of stress can be correlated with numerous factors, such as procrastination (Stead, Shanahan & Neufeld, 2010), lack of physical activity (Gerber, Jonsdottir, Lindwall & Ahlborg,

2014), income level (Reichenberg & MacCabe, 2007) and employment status (Chen, Li, Cao, Wang, Luo & Xu, 2020; Kopp et al., 2008; Xu, 2014). The high workload and stress levels negatively impacts an individual’s well-being and work performance. Work-related stress is increasingly evident in the changing society where emphasis is put on career and job performance (Kopp et al., 2008).

A research conducted on middle managers in Sweden, the Netherlands and the UK indicate an increase in stress where higher levels of workload has led to tension and contradictions in their work. The research shows that surges of management initiatives and policy moves constantly generate elevated levels of uncertainty. Because of this, middle managers in these organizations are becoming “depowered” (Holden & Roberts, 2004). This has been an undergoing development, which has resulted in feelings of pressure and stress in hectic work lives (Holm & Johansson, 2005). A stressful workplace makes mistakes more prevalent (Simon, 1987). Consequently, the development of methods to manage work stress is becoming more significant.

A few main sources of work-related stress include diminished productivity, employee turnover and accidents (Chen, 2017). In a result focused industry such as football, these three sources are significantly prevalent and may therefore explain a vast share of stress creation for football coaches (Gammelsaeter, 2012; Liu & Liu, 2018; Söderman, 2013). In football, there is an immense amount of pressure on coaches to perform. When the performance drops in a team, it is standard to make a change. Often the leaders from the board opt to replace the coach, also referred to as manager turnover. The short-term performance for a team improves by doing this, but there is minimal improvement in the long term. Therefore, replacing the coach could save a team from regulation, but it will not be a long-term solution (Mcteer, White & Persad, 1995). There is a study that claims that the quality of the manager does not impact the predicted turnover rate (Weel, 2011). Nonetheless, the more clubs that choose to displace coaches, the more pressure is accumulated on the present ones (Söderman, 2013).

2.5.1 Consequences from Work Stress

The well-being of people is generally associated with the absence of diseases and various disorders. Individuals’ mental health is an essential aspect of well-being that can be impacted by different diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and cancer. However,

mental health issues are affected by a variety of socioeconomic factors as well, such as national policies, working conditions and living standards. It is progressively more significant to examine the impact of stress and how to manage it since the number of people suffering from mental health issues is rising, where stress is a common factor. Stress can also lead to additional illnesses, such as cardiovascular diseases. Vulnerable groups include minority groups, people exposed to conflicts and young unemployed, which is an emerging group (World Health Organization [WHO], 2013).

However, it is not solely people in vulnerable groups who suffer from mental health issues, indicating that it is a global and substantial concern. The suicide rate is increasing among various groups such as in the military and young people, where it is the second most common cause of death (Bryan & Morrow, 2011; WHO, 2013). The requirement of more social services and funding is evident due to the increased number of people suffering from mental health issues. Furthermore, the mortality rate of premature death of people with mental health disorders is considerably higher than the general population (Kopp et al., 2008; WHO, 2013). It is thus vital to conduct further research in work stress and how to effectively cope with stress and pressure.

2.6 Teamwork

Stress is also a commonly occurring issue in teamwork (Jiang & Probst, 2016; Liu & Liu, 2018). A team is traditionally presumed to be a certain type of task-related group which clearly defines its set of regulations and rewards to the team members (Adair, 1986). The term “group” is often used synonymously with team, however, the focus on goals and accountability varies. Teams consist of individuals with “complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.” (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993, p. 45). There are differences between teamwork and group work that should be acknowledged to reduce disturbing elements for performance, such as stress (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993). As teamwork is becoming increasingly ubiquitous, the usage areas cover leadership, creativity maximization as well as additional structural flexibility (Payne 1988; Peters & Waterman, 1982). Different situations and environments require different structures where an efficient team is one that has a high degree of fit between the two factors. Some structures may be an impediment in certain situations, yet highly advantageous in other environments (Beersma, Hollenbeck & Moon, 2003; Galunic & Eisenhardt, 1994).

Thereby, understanding teamwork enables leaders to construct feasible team structures in certain environments, such as football.

For a team to work effectively, the fit between the members of the team is essential as well. Therefore, it is crucial that individual differences are valued when forming a team. The significance of diversity within a team is highly pertinent in a football team. The various positions require a certain set of skills and approaches, for instance, the goalkeeper needs to have a short reaction time and be attentive to what is happening on the pitch. The midfielders need to be fit and fast since they are positioned between the defenders and forwards, where they have to prevent the other team from scoring as well as create goal opportunities for their own team (Eriksson-Zetterquist, Müllern & Styhre, 2011; Li, Meyer, Shemla & Wegge, 2018). All of the above could therefore be benign knowledge for contemporary football coaches.

There are two prominent differences between football and business teams that need to be mentioned, since they significantly influence team success. First, the number of red cards received for a football team is evaluated to have a remarkable way to worsen the results. When receiving a red card, the player is often suspended for several games, in contrast to receiving two yellow cards in the same game. This may also be explained by the normality of receiving yellow cards in contrast to red. It is common for people, regardless of work, to sometimes receive a warning, while being immediately suspended is far scarcer. This implies that red cards connote added risk for football teams. Second, team sizes may differ a lot although the number of football players on the field remain constant to eleven. This distinguishes football teams, as well as other sports teams, from those in different enterprises without member quantity restrictions (Earley & Mosakowski, 2000; Maderer, Holtbrügge & Schuster, 2014). Another key difference is moral disengagement in sports (Boardley & Kavussanu, 2007), which will be covered in 2.6.3 Moral Disengagement in

Sports.

Research shows that demands on high work performance leads to increased stress levels (Jiang & Probst, 2016). Since demands on individuals can abate by creating a well-organized structure, the coach’s ability to form a diverse team where the individual differences complement each other is crucial. Stressful team environments include high levels of uncertainty. Therefore, the following paragraphs will scrutinize team dynamics

as an assistance in reducing workplace stress in teams (Deming, 2000; Jiang & Probst, 2016; Liu & Liu, 2018), for instance, in football clubs.

2.6.1 Team Dynamics

A diverse team is one that has differences in psychological and demographic attributes. Research has shown that diversity influences several processes, states and outcomes. For example, a homogeneous football team would likely not perform in the same way as a heterogeneous football team would (Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007). In higher european leagues, diversity is becoming more prevalent. With time, even smaller leagues are also becoming more diverse. However, teams, especially football teams, change from time to time as new members join and other members eventually drop out (Maderer et al., 2014). Hence, these variations suggest that teams should be viewed as something dynamic, rather than static.

However, since consideration of time effects need to be taken into account, it is necessary to know that the duration of football players in one club ranges between 1 and 6 years (Teichmann, 2007), which infers that members have time to develop strong social connections together. Team dynamics are still important to be aware of, since the right mixture of experienced and inexperienced players tend to result in success in sports. For instance, diversity brings not only new perspectives, but also different arrays of technical skills and creativity (Gaede, Kleist & Schaecke, 2002; Li, Meyer, Shemla & Wegge, 2018). Thereby, since teams are dynamic rather than static it is significant that football coaches continuously update their team through disparity enlargement with new knowledge and diversity as well as enable efficient social interaction (Li et al., 2018; Maderer et al., 2014).

2.6.2 Team Leadership

Having realized that teams have more collective talent than individuals, yet frequently prove ineffective, it is important to comprehend the nuanced complexities. A leader in the field of understanding teams and team performance suggests that the role of a team leader is simply to insert key conditions which then enables the team itself to succeed (Hackman, 2002; 2009). Another important aspect is timing. Team leaders need to correctly predict when to make team interventions and simultaneously know when to address unpredictable issues within the team (Wageman, Fisher & Hackman, 2009).

Sometimes the best move is to act, other times it is more preferable to simply monitor (Hill, 2010). Other researchers argue that it is in human nature to form and join tribes,

differing only by the prevailing culture in each.Leaders encourage people to join higher

“tribes” with specific attitudes on reality. Hence, leaders are held responsible for members’ mentality as well as the culture developed in a team. (Logan, King & Fischer-Wright, 2008).

There are other perspectives on leaders’ functions (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2017). One view is that the leader should take care of tasks that are not adequately being done, or completely being neglected (McGrath, 1962). Effectiveness is thereby measured in terms of essential tasks performed (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2017), which differs from the previous paragraph, where more emphasis is on people’s view of the world (Logan et al., 2008). Built on McGrath’s approach, team leadership can also involve social problem solving (Fleishman, Mumford, Zaccaro, Levin, Korotkin & Hein, 1991) and reciprocal social relationships (Zaccaro, Rittman & Marks 2001). Naturally, the more aspects that are included for a leader, the more stress and pressure is put on the leader and this infers challenges to the integration of team and leadership (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2017).

2.6.3 Moral Disengagement in Sports

The literature on groups and teams demonstrates that the behaviors and actions of members are profoundly impacted by the existing culture and the dynamic within the team (Eriksson-Zetterquist et al., 2011; Schein, 2004). Historically, the focus in sports has been victory and a sense of achievement where people justify violence and misconduct in order to win. This behavior is referred to as moral disengagement, where an individual believes that ethical standards are not applicable to oneself in a certain situation and is far more prevalent in contact sports than other activities. Thus, this illustrates another difference between sports and businesses. The disengagement can be made by diffusing or displacing responsibility and moral justification. Factors contributing to high levels of moral disengagement among male athletes include the significance of victory, gender norms and the physical contact, which can easily cause negative emotions (Bandura, 1991; Boardley & Kavussanu, 2007; Hodge & Lonsdale, 2011; Tsai, Wang & Lo, 2014). Therefore, if the football coach can alter the significance of these factors for the players, the negative emotions may abate.

In other terms, since members are formed by environment, and leaders have a responsibility to generate a fair and developing environment, leaders are pressured to influence their followers in a positive manner. Research shows that male athletes participating in team sports with physical contact, such as football, rugby, and hockey, engage in antisocial behavior more than athletes in other sports (Tsai et al., 2014). Moreover, there is a link between traumatic stress and moral disengagement, which further incentivizes the decrease of negative pressure in the everyday environment (Coker, Ikpe, Brooks, Page & Sobell, 2014). Hence, reducing traumatic experiences and rendering will likely result in fairer sport performance and less stressful environment. Furthermore, team members may display higher levels of moral disengagement if the coach is considered authoritative and controlling. The number of players participating in antisocial behavior and the degree of engagement in such behavior can diminish if the coach is supportive and creates a moral climate where trust, collective responsibility and care are fundamental (Marasescu, 2014). This further illustrates the importance of a coach’s behavior and leadership style.

2.6.4 The Dark Side of Teamwork

There has been growing oppression in organizations to glorify team works in stereotypical ways that tyrannize individual members by reducing flexibility, conflicts and coercion - features that often may benefit a group in terms of honesty, transparency and qualitative findings. Sinclair (1992) studies prevailing ideologies on the existing pattern in organizational teams and proceed from four sets of assumptions: groups tend to have a positive effect on dealing with tasks and corruption; individuals are motivated to work in teams to fulfill their own as well as the organization’s objectives; participative leaders are perceived to bring superiority; power, conflict and emotions disrupt group work. The traditional view on group work is very positive, however, Sinclair (1992) suggests the opposite and that it brings larger amounts of stress. The introduction of uncertain elements, such as ambiguous peer judgments, tend to result in a tension surge (Jiang & Probst, 2016; Sinclair, 1992).

Per contra, complete awareness of one’s work responsibilities and requirements leads the worker to perform adequately (Korman, 1971). The decrease in performance is also explained by Katzenbach and Smith (1993), in a study evaluating team effectiveness and performance impact. The study explains that when moving from a working group towards

a high-performing team, some become referred to as “pseudo teams”, meaning teams that recognize potential but fail to beset the benefits (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993). More research shows teamwork failure exists on account of poor management understanding of team dynamics (McCann & Margerison, 1989) or lack of sharing personal values (Kets de Vries, 1999). Also, as mentioned in 2.2 Contemporary Views on Leadership in this literature review, the increasing number of ethnically diverse teams has prompted research where cultures, ethnicities and gender are taken into account, all of which mention separate problems with teamwork (Canney Davison, 1994).

The Marxist binary terms “manager” and worker”, as advocated by Learmonth & Morrell (2017), would fail to lift up certain reinforcement features that contemporary leadership terms “leader” and “follower” bring (Collinson, 2017). This debate demonstrates the remaining uncertainties regarding leadership and management in numerous industries, suggesting that leadership often can be significantly unclear, both for experts and executioners. Realizing the existence of countless shades of leadership, and especially that there does not seem to be one contemporary definition that is the most efficient, football coaches and business leaders do have to cope with a dark side of teamwork (Deming, 2000; Sinclair, 1992).

2.7 Different Types of Pressure

In many industries, pressure is increasing. For suppliers delivering goods, there is a constantly growing pressure to deliver goods on time and thus reducing logistic cycle times and lead times (Tomas & Hult, 1997). This pressure can impact relationships between trading businesses depending on the magnitude. Apart from the magnitude, frequency and contribution have also been defined as evaluative criteria for coping with time pressure, using qualitative interviews and a grounded theory approach. It is important to acknowledge that there are different types of pressure, and thus likely different types of pressure/stress for football coaches as well. A model suggests that higher levels of pressure should be dealt with more disengaging strategies, such as withdrawal or termination. Meanwhile, lower levels of pressure should be dealt with more utilizing approaches, such as problem solving or responding. If the pressure levels are relatively mediocre, defending methods, such as re-appraising and protecting could be

interplaying actors, trading businesses in this case, should increase or decrease the ties (Thomas, Esper & Stank, 2011).

While managers in both industrial business and football clubs experience pressure, the primary problem is the stress that it brings as it affects efficiency, performance and individuals’ health (Beilock & Decaro, 2007; Covert, 2012; Rimmer, 2018; Söderman, 2013). In the English health sector, the proportion of employees mentally unwell because of work stress increased from 36.7% in 2016 to 38.4% in 2017 while the share of workers able to deliver the care they aspired dropped from 68.2% to 66.8% during the same 12-month period (Rimmer, 2018). This directly suggests that stress management is highly pertinent for contemporary leaders. When it comes to coping with stress in sports, former Swedish handball coach Bengt Johansson claims that growing familiarity outside the pitch is key to diminish tension and pressure that often might occur otherwise (Söderman, 2013). Another study found that individuals with better working memory tend to simplify their strategies when pressure increases which is beneficial in situations that require less complex solutions (Beilock & Decaro, 2007).

2.8 Coping with Stress

One of the major issues for football coaches is how to handle the stress that they experience. The way to handle stress is usually referred to as coping and has been a researched topic for several years. People find themselves in stressful situations for a variety of reasons and the emergence of stress can be due to numerous factors, such as workload, employment status and the level of physical activity (Chen et al., 2020; Gerber et al., 2014; Sianoja, Kinnunen, Mäkikangas & Tolvanen, 2018). Stress can also arise from interpersonal conflicts, which is an inherent characteristic of human behavior (O’ Driscoll, 2013). Football coaches are not resistant to stress and can get involved in conflicts with players and other people within the team, they experience stress even when there is a day off. In football, the inevitable truth is that one team has to lose every game, there is always a winner and a loser. A tie may not necessarily be considered a loss; however, it has a significant impact on the scoreboard and often results in one team remaining in the league while the other one is out (Williams, 2020).

The way people cope with stress is individual, however, conflict avoidance has traditionally been regarded as the optimal way of handling conflicts that emerge in the

workplace. A widely known strategy for dealing with stress is to “fight” or “flight”. Fight, also referred to as problem-focused coping, is when an individual engages in direct actions in an attempt to reduce or remove the stressor. Flight is an emotion-focused way of coping, known as the previously mentioned conflict avoidance, where the focus is on altering the emotional reactions to the stressors (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Selye, 1956). Research shows that one way of coping with stress is not always preferable over the other, the most suitable method to handle stressors depends on the circumstances (O’ Driscoll, 2013).

Moreover, there is proactive coping, where people tend to anticipate potential stress factors and therefore develop a reaction before the situation emerges. In contrast, some react to the issue after it has risen, known as reactive coping (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997). Since the approach to managing stress is highly individual, it is immensely difficult to acquire accurate and reliable information. Therefore, the knowledge in stress coping is considered limited (Dewe, O'Driscoll & Cooper, 2010). A more effective method of managing stress in the workplace could be to apply an integrated approach by first focusing on reducing work stressors within an organization and subsequently provide support for individuals if needed (Dewe, 2004).

2.8.1 The Impact of Mental Disengagement

There exist several factors and methods that can facilitate coping with stress and resilience to work stress, such as mental disengage-ment and physical activity. Mental disengagement demonstrates that an individual’s ability to detach from work impacts the experienced level of stress and exhaustion. A person that has a high workload and a high detachment ability during free time experiences lower levels of exhaustion in comparison with individuals who have a high workload and low detachment (Sianoja et al., 2018). A football coach that has participated in the highest league in Finland and experienced the stress associated with being a coach expressed: “The ‘pressures’ of the job do not take a vacation for a day. They are with you when you sit on the couch, lay on a sun lounger …”

(Williams, 2020). It appears to bechallenging to detach from work during free time as a

2.8.2 Physical Activity and Stress

Nonetheless, physical activity appears to contribute to a certain degree of resilience to work stress. Regular exercisers report better mental health than the ones who do not, even though the experienced stress level is similar (Fan, Das & Chen, 2011; Fondell, Lagerros, Sundberg, Lekander, Bälter, Rothman & Bälter, 2011; Gerber et al., 2014). There are three factors that could explain why people who exercise regularly cope better with stress. Firstly, engaging in physical activity enables mental disengagement, which is proven to result in a lower level of exhaustion. Secondly, higher fitness levels can contribute to a distinct way of reacting to cognitive and psychosocial stress factors. Thirdly, physical activity can prevent stress-related sleep problems (Gerber et al., 2014). However, the statement presented earlier indicates that coaches do in fact experience an immense amount of stress regardless of the level of physical activity.

2.9 Summary

This framing of reference is intended to mediate a picture of existing knowledge prior to our empirical research and analysis. As visible in the literature review, leading in stressful environments has been emphasized by presenting theories that will aid analysis in later chapters in this paper. Occupational stress has clearly been identified to be influenced by leadership. This suggests football coaches not only cope with their own stress but also players’ stress, which further puts pressure on the team leader. In our empirical study, we will further investigate this phenomenon.

There are several contributors to stress and challenges with leading in stressful environments. In the previous paragraphs, it has become evident that time, uncertainty, lack of knowledge and absence of relevant tools bring stress to workers across multiple industries. Furthermore, the red cards and moral disengagement that appear in the football setting eventuate added stressors for leaders in these environments. Lastly, static and erroneous team leadership is the final factor that potentially may harm a football team’s performance and therefore leadership has been emphasized in earlier sections of the literature review.

To cope with stress, leaders may conduct different approaches. An efficient strategy is applying an integrated approach by first focusing on reducing work stressors within an organization and later providing support for individuals if needed. Additionally, mental

disengage-ment and physical activities constitute more stress coping methods that football coaches can utilize to decrease stress levels. Due to dynamic team structures, leadership and stress coping methods may in theory differ significantly from team to team since distributed leadership can take many different forms and still be effective. Hence, our empirical study will contribute significantly to leadership literature in stressful environments.

3

Methodology

In this section, research approach, strategy and method are presented and justified. Furthermore, techniques that will increase the trustworthiness and the reliability of the research are portrayed. Lastly, the data analysis procedure is described.

3.1 Research Philosophy

The aim of this research is to develop a theory or ideas that may improve or contribute to the understanding and knowledge of leading in a stressful environment, how to manage stress in a more efficient manner and the pressure associated with being a coach. The research was classified as exploratory and basic since there is a lack of existing literature regarding this subject. In order to conduct scientific research, there are philosophical frameworks that act as guidelines. The frameworks are known as research paradigms or scientific ideologies, and there exist numerous ones (Collis & Hussey, 2014). There are various paradigms, such as positivism/empiricism and interpretivism/anti-naturalism (Zachariadis, Scott & Barrett, 2013).

The ontological assumption of the researchers is that reality is subjective and thus socially constructed. It is assumed that social reality is affected when investigated and the purpose is to generate theories or insights by interpreting data in order to gain an understanding of the social phenomenon in a certain context (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Interaction with the people being interviewed was made and the knowledge was accordingly derived from the participants and considered valid knowledge, which conforms with the epistemological assumption of the interpretivist view. The previously mentioned statements on the researchers’ view on reality and the derivation of insights, are in accordance with the interpretivism paradigm (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Creswell, 2014), which hence acted as the framework for this research. An abductive approach was

applied, which will be further elaborated in sections 3.2 Research Design and 3.3 Data

Collection.

While interpretivism assumes that reality is subjective, positivism assumes that reality is objective, independent of people and that there is only one reality. Thus, according to positivism, investigating social reality does not have an impact on practical reality and is a measurable phenomenon (Creswell, 2014). The research in a positivist study is based on empirical evidence and assumes that knowledge is “positive information” since any rationally justifiable assertion can be validated by logical or mathematical evidence (Walliman, 2011; Charmaz 2006). Therefore, statistical analysis and quantitative research data are commonly used when conducting positivist research. In that scenario, the purpose would correspondingly be to develop theories by hypothesis testing and applying deductive approach (Collis & Hussey, 2014). However, for this particular research, the paradigm is not applicable since the nature of reality does not correspond with the researchers view on reality, which is that reality is subjective and socially constructed. There are additional research philosophies, however, those will not be discussed due to the low relevance to this thesis.

3.2 Research Design

As stated previously, there is currently limited literature regarding the researched subject and the knowledge in the topic is therefore lacking. This research is based on a grounded theory approach. Grounded theory is considered favourable for us since it not only allows researchers to perpetually update what they devise, but also explicitly present how these proceedings may be executed (Akhter, 2018; Charmaz, 2006). Grounded theory encourages theoretical insights to emerge from empirical data and does not commence with a preconceived theory already in mind (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Furthermore, an abductive approach was applied where data was collected and analyzed in a thematic approach in order to generate theoretical insights that contributes to further knowledge in the field of leadership and methods for managing stress (Malhotra, 2017; Shepherd & Sutcliffe, 2011). The abductive reasoning begins with empirical data and possible explanations for the data, which later transforms into potential hypotheses that could be tested (Rosenthal, 2004). “In brief, abductive inference entails considering all possible

checking them empirically by examining data, and pursuing the most plausible explanation.” (Charmaz 2006, p. 103).

The grounded theory is developed on the basis of a single case study. The single case study is based on the phenomenon of stress and coaches’ strategies of coping with stress. Acquiring insights from a single case study is chosen since rich empirical evidence is produced and in-depth knowledge is obtained of the phenomenon, where the insights derived in this research could be tested in a future quantitative study (Yin, 1994). Moreover, qualitative research is considered appropriate for this research because the purpose is to understand how football coaches lead in a stressful environment and a qualitative approach is useful when studying human behaviour under certain conditions (Daft, 1983; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Quantitative research is not suitable for this specific research question, as this research attempts to describe and understand the phenomenon and instead measure it in terms of scale (Rowlands, 2003). For instance, quantitative research and data would be appropriate to utilize if the purpose had been to examine how often football coaches are using a certain tactic to cope with pressure. In this paper, scrutinizing leadership in stressful environments, theoretical insights were developed from interpretations, not explicitly stated in numbers.

This study commences with the data retrieved from interviews held with members of various football clubs. Following the grounded theory approach, these data generate rich descriptions of the studied phenomenon, based on empirical observations, interactions and materials (Charmaz, 2006), related to coaches in football environments. Since the abductive approach is the process of a rational inference developing from minute description to hypothesis (Czarniawska, 2014), the combination of grounded theory and an abductive approach is sensible in this study. Furthermore, in this research design, the researchers are not passive observers, rather the researchers are reflexive and make assumptions about reality (Charmaz, 2006).

3.3 Data Collection

Primary and secondary qualitative data was collected and analyzed in order to acquire information from various sources. Primary data was collected to acquire data on the specific research problem (Hox & Boeije, 2005), in this case how to lead in a stressful environment. This was achieved by conducting interviews. The construction of the

interviews will be further elaborated under section 3.4 Interview Design. The secondary data acquired and reviewed was literature in the form of journals, reports, books and interviews to achieve a broader perspective on the topic. Furthermore, secondary data facilitated the development of theoretical insights since the acquired data could be compared to the findings from the primary data.

The literature was primarily collected from Primo, the library database of Jönköping University. An additional database used is Google Scholar. Comparable to Primo, the search engine is useful in this paper since it has an array of academic sources in various subjects and forms. The databases are used since it has a wide variety of different academic sources, such as journals, books and articles. This research utilizes all three of those. These sources on are peer-reviewed as well, meaning that the sources are reviewed by other scholars or people with similar competences as the author, which consequently enhances the validity and quality of the reviewed sources (Nicholas et al., 2015). Furthermore, the literature used mostly consists of relatively new sources, published in the past ten years at the time of writing, to make the secondary data more precise and reliable. Naturally, a few sources are older but considered relevant to this paper since the insights in those sources appear to remain pertinent.

A systematic approach was applied which provided the researchers with a robust overview of the existing literature of the topic. In turn, this overview ensured that key publications and relevant literature were identified and not overlooked. Keywords were used in Primo as well as in Google Scholar in order to find relevant and useful sources. The keywords included in the data search were leadership, mental health, stress,

teamwork, turnover and sport manager. Furthermore, a literature review matrix was

developed in Excel, consisting of several sources used in this research, which help us reduce irrelevant search results and save time. The key points in those sources were briefly summarized to enable the researchers to maintain a record and revise the literature if needed. Therefore, it is easier to reproduce the search strategy for the literature review (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Curtin University, 2020; Garrard, 2014).

3.4 Interview Design

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to acquire primary data and retrospective as well as real-time accounts for this research (Gioia, Corley & Hamilton, 2013). The

structure enables the researchers to ask follow-up questions that are tailored depending on the answers of the participant. Open-ended questions were used to allow participants to freely lead the interview to any direction where theory can emerge (McCracken, 1988). Responses were gathered from several individuals in various football clubs, to obtain a broader understanding of the phenomenon stress in a more complex way. The interviews were conducted with one participant at a time to ensure that the interviewee was able to express their own thoughts without the influence of others.

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak at the time of writing, the interviews were conducted through Skype or on phone. The use of Skype led to technical issues, such as slow connection, nonetheless; it was extremely efficient since it was not possible to meet in person to and have a face-to-face interview. Background questions were asked first, such as how long the individual has been a part of the team etc., to gain some background information before asking questions that were formulated to answer the research question (see Appendix 1 and 2). The interviews were conducted in English to facilitate the communication between the researchers and the participants.

With the permission of the participants, the interviews were recorded and notes were taken simultaneously during the interviews. The participants signed a GDPR consent form before the interview (see Appendix 3). The recordings were then transcribed to avoid any confusion or lack of information in the notes and to allow revision of the material. An agreement was signed by the researchers and the interviewees before the start of the interview to ensure that the participants were aware of the use of the material and how the material would be handed if an individual would wish to withdraw from the research. The ethical implications of this study are discussed further in a section with the corresponding headline.

3.5 Sample Selection

As mentioned in Research Design, the participants were selected through theoretical and convenient sampling. Theoretical sampling was applied to ensure that the selected interview participants were suitable and effective in demonstrating the researched relationship (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). The convenient sampling was made by reaching out to those who we had some direct or indirect connection to. This was on the basis of the current pandemic, limiting the possibility of face-to-face interviews. The

selected participants are from various teams in England, Finland, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia and Sweden. The teams are competing in different leagues on varying levels. Since cultural differences may contribute to increased variation in responses, the categories and themes detected in our analysis are probable to reflect stress coping methods prevalent in the environment of football in particular, rather than stress coping methods prevalent in a designated country. On that regard, ethnical diversity is favourable for our research. However, having five out of six respondents originating in north western Europe, some limitations in generalizability are implied.

A total of six people was interviewed, consisting of three football coaches and three football players. Although we are researching coaches’ methods to cope with stress, players’ perspectives plausibly generate increased trustworthiness to the responses retrieved from coaches. For instance, players’ views on strategies can be useful since they only witness the execution phase, not the planning that it is built upon. On the contrary, coaches devote far more time into determining what to do and their views may hence be afflicted by the planning phase. Therefore, the coaches may believe that the implementation of the strategies is made efficiently but the players may view it differently. This thesis analysis implemented strategies prevailing in contemporary football teams, not planned strategies for the future. The first coach is the coach for one of the most successful youth teams in the world, the second and third coach each has numerous years of experience as football coaches for teams competing in the highest leagues in Europe. The coaches have 10, 20 and 30 years of experience as football coaches, respectively. The experience of the players varies from 15 and 20 years and all are field players.

The length of the interviews were approximately 60 minutes each. The football coaches were interviewed to acquire knowledge of the experienced stressors, such as from investors, players and supporters. The way the coaches cope with the stress is significant to this study, for instance, if they use any specific methods such as mental disengagement or physical activity. The relationship between the coaches and their players is essential to understand if the coping methods does in fact have an impact on performance and since the applied leadership style can have a significant impact on the players (Marasescu, 2014). Furthermore, since players are directly affected by the decisions made by their coaches, their perceptions are highly relevant to obtain a broader perspective of leading

in a stressful environment. Figure 3.1 displays each of the participants together with the date of the conducted interview.

Participant Date Coach 1 April 14th, 2020 Coach 2 April 14th, 2020 Coach 3 April 15th, 2020 Player 1 April 17th, 2020 Player 2 April 22nd, 2020 Player 3 April 27th, 2020

Figure 3.1. Log of Data Gatherings.

3.6 Data Analysis

The analytical goal of this paper is to identify patterns and themes associated with stress in the football environment, leading to the creation of a framework. The methodology used in this thesis is thematic analysis and is based on the six steps described by Braun and Clarke (2006): familiarization, initial coding, searching for themes, reviewing, defining the themes and lastly, produce and finalize the analysis and the report. Note that there is no clear agreement on how the thematic analysis should be used. This provided us researchers with extensive freedom in our analysis and was beneficial to us as novice researchers because it is a diverse and flexible methodology that is uncomplicated compared to others.

In our analysis we combine the thematic analysis with grounded theory approach where the themes are the same as the categories defined in grounded theory. This approach is constantly comparative, generating new aspects as the frame of the study is subject to a continuous design (Akhter, 2018). It is explicitly stated that grounded theory methods may serve in combination with other qualitative data analysis approaches (Charmaz, 2006). The approach is appropriate for numerous different theoretical frameworks and suitable for this research. The thematic analysis is in accordance with the interpretivism paradigm as well since it allows the researchers to interpret and derive insights from the

participants (Avery, 2016). Furthermore, grounded theory offers versatile tools for interpreting and elucidating data (Charmaz, 2006).

There was a limited amount of existing research on our subject, however, there were some conclusions that could be drawn from the literature review, which led us to use an abductive approach. The approach is leaning more against the theoretical thematic approach due to the researchers theoretical and analytic interest in the subject, making the thesis more explicitly analyst driven. Determining by which level the themes would be analyzed was also needed. The semantic approach where the themes are identified on the surface or explicitly, appeared to be the most suitable for this research since an interpretation was made based on what the participant said and not beyond (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

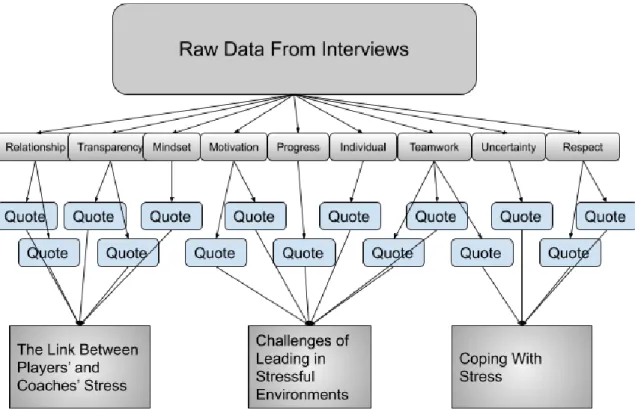

The primary data was collected by conducting interviews and, in accordance with the first step in the thematic analysis, the material was transcribed which allowed the researchers to familiarize with the data. Since the research has an abductive approach, the coding and searching for themes were worked on simultaneously. Accordingly, the second step in this analysis was to search for themes and then continuing with coding the data by color coding in an excel sheet where all the players and coaches were assigned their own unique color. By doing this we found enough empirical data for all the different themes. The use of any kind of analytic software was not required in the analysis. The data was once again reviewed to ensure that each theme used was pertinent and versatile. The subsequent step was to define each theme, which was done simultaneously as the last step, to produce the finalized report. All of the themes were individually analyzed and then merged together, resulting in three main findings (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The sequence of the steps can be seen in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2. Process of Data Analysis. These are the six steps of the thematic analysis

presented by Braun and Clarke, (2006).

As mentioned earlier, the objective of this research is to obtain more insights about the phenomenon stress and how to lead in the football environment, the thematic analysis method enables us to deepen our understanding and develop a framework. By using visual

aid, it was possible to have a graphical representation of how the process from raw data to findings occurred, displayed in Figure 3.3. In other words, it is a static picture of a dynamic phenomenon illustrating the process of identifying our main findings (Gioia, Corley & Hamilton, 2013).

Figure 3.3. Overview of Thematic Analysis. This figure displays how the quotes are

intertwined between the nine themes and the three aggregate dimensions defined by the researchers. The model is constructed by the researchers.

4

Empirical Findings

In this section, the empirical findings derived from the interviews are presented. The interviews began with two short questions regarding the participants experience in the football industry as well as the experience in the current team. The interviews were then divided into two parts. The first part consisted of questions regarding the participants view on leadership while the second part involved questions about stress and pressure.

4.1 Views on Leadership

Even though all the three coaches had various years of experience, ranging between 10 and 30 years, their view on leadership aligned in certain aspects. When asked about the

coaches’ definition of leadership, all three responded that leadership is about leading by example and helping others to develop:

For me leadership is the one that makes the rest of the group capable of getting into strengths. (Coach 1)

The leadership within a first team environment is more you have to win game so it’s showing the players how they can get the best out of their own. (Coach 2) A lot of people can lead by example by maybe be the first at training or trying to train

the hardest. (Coach 3)

The leader’s ability to bring the best out of the employees, or in this case the players, and helping them to grow and develop individually is highly significant and is one of the main tasks of a leader. The three players agreed that a leader should be motivating and helping each individual, whereas one also considered a leader to be someone decisive. One of the coaches acknowledged the fact that there are various forms of leadership, such as the more authoritative one that is present in the military and the more laissez-faire leader that does not necessarily interfere that often but has valid points once intervening:

When they have something to say it's always very pointed and very thoughtful and very provoking. (…) There are so many different forms of leadership that I think it’s hard to

just define it by saying it is “this”. (Coach 3)

Furthermore, two coaches emphasized that it is especially significant to lead by example when working with younger players since they may look up to the coaches. Although it is important to help them develop their strengths, it is also essential to help the players learn new things. Through the leadership, the coaches can teach the players what good morals and good sportsmanship are as well as the significance of having respect for the game itself. One of the coaches compared the process of leadership with nurturing children and one player agreed with that perspective:

It's certainly showing them the way to behave and the way to act, a bit like the way you would want your children to behave. (Coach 2)