Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Spring 2018

Bumblebees, Fireflies & Ants at

Coworking Spaces

Inter-organizational Collaboration Patterns within

Coworking Spaces

Adekunle Babatunde Pedram KhalighiAbstract

Coworking spaces, an example of the sharing economy concept, refers to shared workplaces that mostly freelancers, entrepreneurs and other actors of the knowledge industry utilize for the purpose of flexible sharing of space, ideas and knowledge. Previous research reveals that the proximity of occupants sitting together in a shared office space does not necessarily lead to inter-organizational collaboration. Knowledge sharing and inter-organizational collaboration tend to be perceived by occupants and managers of coworking spaces as incidental or a secondary aim. In the same view, coworking spaces tend to be perceived as service providers rather than a community where collaboration can be fostered. A potential solution, in this case is, the initial understanding and categorization of occupant types and their evident collaboration approaches which may result in the managers and policy makers of coworking spaces knowing what conditions to put in place in order to foster collaboration.

The novelty of this research and contribution to theoretical knowledge lies in the development of insect metaphors to simplify the understanding of coworking space occupant types and their corresponding inter-organizational collaboration approaches as it affects their willingness or lack thereof to engage in collaboration.

The research data was gathered through semi-structured interviews with a selection of occupants across three selective coworking spaces in Malmö. The findings of this research indicate that there are correlations between occupant types, their collaboration approach and their willingness to collaborate. Therefore, the effort to promote collaboration at coworking spaces needs to be a responsibility shared between the occupants and the community managers.

Table of content

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background – Sharing economy and coworking spaces ... 1

1.2 Collaborative issues in coworking spaces ... 2

1.3 Purpose ... 3

1.4 Research questions ... 4

1.5 Structure of the thesis ... 4

2. Key concepts and analytical framework ... 6

2.1. Coworking spaces and inter-organizational collaboration ... 6

2.1.1 Coworking spaces ... 62.1.2 Inter-organizational collaboration and coworking ... 7

2.2 Analytical framework ... 9

2.2.1 Good neighbours and good partners coworking configurations ... 92.2.2 Three inter-organizational collaboration approaches ... 11

Cost-related collaboration ... 11

Resource-based collaboration ... 12

Relational collaboration ... 12

2.2.3 Three occupant types as metaphors ... 14

3. Methodology and methods ... 17

3.1 Philosophical view ... 17

3.2 Qualitative research ... 17

3.2.1 Case selection ... 183.2.2 Semi-structured interview design ... 19

3.2.3 Limitations ... 20

3.2.4 Delimitations ... 20

3.2.5 Data collection ... 20

3.3 Sampling ... 22

3.4 Coding, metaphors and categorization of data ... 22

3.5 Validity and reliability ... 24

3.6 Quality and ethics in research ... 24

4. Data analysis and main findings ... 25

4.1 Occupants’ inter-organizational collaboration patterns ... 25

4.2 Correlation between occupant types and collaboration approaches ... 29

4.3 Positioning of interviewees as occupants types ... 32

5. Discussion ... 35

5.1 Commonalties and differences of coworking spaces ... 35

5.2 Shared leadership and responsibility ... 36

6. Conclusion and managerial implication ... 39

6.1 Practical managerial implication ... 39

6.1.1 Recommendations by occupants ... 396.1.2 Observations ... 40

6.2 Conclusion ... 40

6.3 Future research ... 41

Bibliography ... 42

Appendixes ... 46

1. Appendix; Interview guide ... 46

2. Appendix; Interview transcripts ... 47

3. Appendix; Fieldwork and observations ... 63

List of Figures

Figure 1 – Thesis structure ... 4Figure 2 – Coworking centres relative to workspaces ... 6

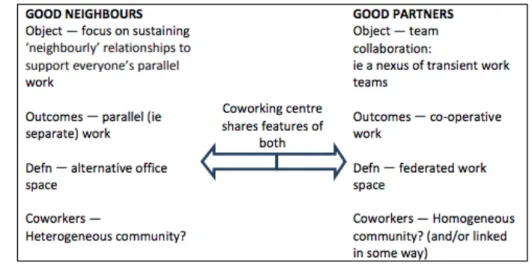

Figure 3 – Good neighbours versus good partners configurations ... 10

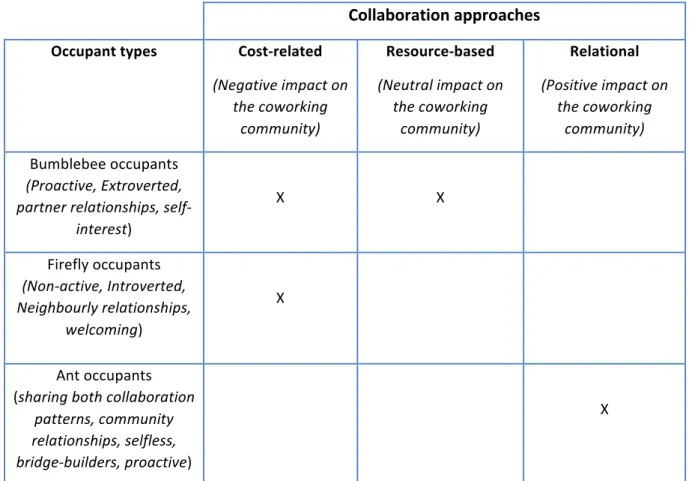

Figure 4 – Three collaboration approaches interrelation to coworking space types ... 13

List of Tables

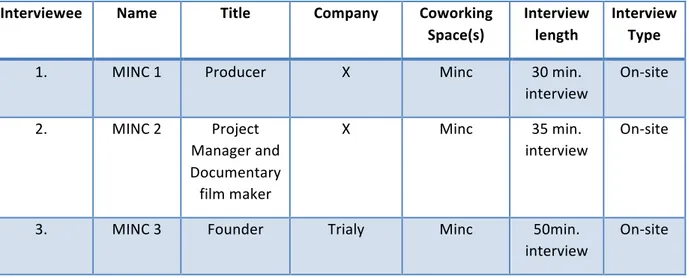

Table 1 – Matrix of correlation between occupant types and collaboration approaches ... 16Table 2 – List of interviewees ... 21

Table 3 – Positioning of interviewees as occupant types and insect metaphors ... 32

Glossary – Keywords and abbreviations

CBRE – Commercial Real Estate Service FirmCommunity of practice – Practice of knowledge sharing Coworking space – A shared workplace

Coworking – Working together in parallel with other members

Formal collaboration – Collaboration that leads to partnership (e.g. partners, clients)

Informal collaboration – Collaboration in form of knowledge sharing, socialization and interaction Inter-organizational collaboration – Working together with other organizations as cross-collaboration Occupants – Members who occupy space in a shared workplace/coworking space (for free or rent) Proximity – Closeness

Remote workers – Employees hired by a company that mainly work from home Shared leadership – Distributed and decentralized leadership

Sharing economy – Concept based on share of resources through peer-to-peer networks Sustainability – Refers to the balance between social, economic and environmental interests.

Introduction

1.1 Background – Sharing economy and coworking spaces

In recent years the sharing economy has emerged in several industries, where the core concepts of it are built on the sharing of resources through peer-to-peer networks and collaborative consumption. This sustainable form of consumption and access to services/products without the burden of ownership has developed various well-known sharing economy initiatives (Aster & Boynton, 2013). One of many disruptive sharing economy initiatives is coworking spaces, which ensures efficient co-working space usage, the share of ideas and resources (Aster & Boynton, 2013). Coworking spaces are shared workplaces utilized by different sorts of knowledge professionals, mostly freelancers and entrepreneurs, working in various degrees of specialization in the vast domain of the knowledge industry (Gandini, 2015).

Several authors have defined sharing economy from different perspectives but the common thread in most of these definitions showcase the concept as an alternative way to utilize resources in a more just and sustainable way. Among the very many definitions found, these select few have more correlation to the phenomenon of coworking spaces that this academic study intends to explore: The sharing economy refers to forms of exchange facilitated through online platforms, encompassing a diversity of for-profit and non-profit activities that all broadly aim to open access to under-utilized resources through what is termed ‘sharing’. Mathews (2014) defines sharing economy as follows: “The sharing,

gig or on-demand economy are catch-all terms for technology-based ‘peer-to-peer’ firms that connect people for the purposes of distributing, sharing and reusing goods and services” (as cited in

Ravenelle, 2017, p. 2). Botsman and Rogers (2011) defines sharing economy as the allowance of various under-utilized resources such as homes, tools, clothes, and vehicles to be used more effectively for bringing people together, for encouraging the development of more user-centred services and for constituting new forms of entrepreneurship (as cited in Bradley & Pargman, 2017). Attitude towards consumption has shifted in recent years and brought increasing concern over ecological, societal, and developmental impact (Hamari et al., 2016). As a result of this, communal sharing via several online platforms can be said to be evident in several areas of commerce. In the course of reviewing some literature, it was found that the same concept ‘sharing economy’ was alternatively referred to as peer to peer based activity-based sharing, collaborative consumption and so forth.

The increasing demand for coworking spaces is rapidly gaining traction in various countries, including Sweden. In parallel, the sharing economy has also played a pivotal role in this workplace paradigm shift, which has disrupted traditional serviced offices and is perceived as being the future of work (CBRE Research Part 1, 2016). “They feel part of a community. Connections with others are a big

reason why people pay to work in a communal space, as opposed to working from home for free or renting a nondescript office. Each coworking space has its own vibe, and the managers of each space go to great lengths to cultivate a unique experience that meets the needs of their respective members”

(Spreitzer et al., 2015, p.28-30). More workers are shifting away from traditional office environments in search of communal spaces that consist of flexibility, collaboration, knowledge sharing and an invoked sense of community. Coworking spaces are also defined as the “sustainable office phenomena”, where share of resources, space and supplies may ensure environmental and economic sustainability (Weeks, 2013). Moreover, co-shared workplaces are built on a core belief that collaboration and community enables innovation and a meaningful work environment. Based on a research conducted by the real estate firm CBRE, more than fifty percent of its respondents quoted that the community as one of the most valuable factors in their co-shared workplaces, while 30 percent believed that collaborative opportunities were the key value (CBRE Research part 1, 2016). Co-shared

workplaces are often perceived as being applicable or appealing to merely entrepreneurs, startups and freelancers. However recent research indicates that corporate or traditional offices are slowly adopting the characteristics of co-working spaces (Spreitzer et al., 2015). Additionally, workers are requiring more flexibility, autonomy and the sense of community from their traditional workplaces. In traditional workplaces knowledge sharing, interaction and sense of community are often occurring during work meetings (Spreitzer et al., 2015). According to the CBRE report, traditional workplaces are experiencing this paradigm shift, where the one size fits all strategy is shifting to a one size fits no one. This is why coworking places are the future of work and will possibly be integrated into traditional serviced offices or workplaces (CBRE Report Part 2, 2016). ”People come in for the

flexible situation and they walk out with an appreciation for the community and culture”. (CBRE

Report Part 1, 2016, p1.0). Furthermore, the communities of coworking spaces also provides knowledge sharing across industries and professions, which is not the case with traditional or corporate workplaces (Bennett, 2015). The importance of community and collaboration is evident, however the proper settings or work environment is required to support the sense of community (CBRE Research Part 2, 2016). Another crucial factor is the leaders of coworking spaces that can invoke sense of community by leading through inspiration with examples of creativity, collaboration, integrity and transparency. Leaders of coworking spaces are often referred to as community managers who have a pivotal role in building the community (Bermudez, 2015).

1.2 Collaborative issues in coworking spaces

Leforestier (2009) states that: “In order to directly address the latter issue, we should take into

account that since the earliest coworking phenomenon reports, the primary rationale of coworking is not, in principle, business-oriented. On the contrary, a significant element that seems to characterise coworking practices is an ‘open source community approach’ to work, intended as a collaborative practice that seeks to establish communitarian social relations among the member-workers” (as cited

in Gandini, 2015, p.196). Based on various publications and research reports within the field of coworking spaces, there is the popular notion that coworking spaces are supposed to be an avenue to promote resource sharing, collaboration, and knowledge creation, but is this indeed the case. Are businesses housed in the same coworking space collaborating. Moreover, what is the responsibility of occupants and leaders of coworking spaces as community managers in fostering community building and collaboration. Recent critics have also raised concerns about whether coworking spaces has the full potential to be platforms for collaboration and knowledge creation or if it is just a coworking bubble (Gandini, 2015). Taking a cue from Castilho and Quandt (2017) whose work looked deeply into the development and measurement of collaborative capability at coworking spaces, the research will intend to take a step backwards to analyse if indeed coworking spaces can, in fact, serve as a platform that fosters collaboration and community building within individual spaces hence the term inter-organizational collaboration (Castilho & Quandt, 2017). Moreover, Castilho & Quandt (2017) discusses two types of coworking spaces, one is convenience sharing coworking spaces, which fosters collaborative capability through knowledge sharing and execution. Second is community building coworking spaces that foster collaborative capability by enhancing a creative and individual field for the collective.

While reviewing more literature about coworking spaces, some additional specific interpretations were discovered, for instance, Castilho & Qandt (2017) defines coworking spaces as a space that offers the promise of a collaboration capability that generates benefits in terms of firm competitiveness. However, there is also a non-competitive dimension of coworking as well (Gandini, 2015). Although some occupants (coworkers) within coworking spaces work within a similar industry, they tend to not feel competitive and act more as complementary actors rather than competitors. This may have an

impact on the organization or firm’s competitiveness. Nonetheless, this may also relate to the cultural and social practices of collaboration within coworking spaces, such as shared values and beliefs (Castilho & Quandt, 2017). The philosophy behind coworking spaces is often defined by a few common characteristics, which is also described as core values. These core values are collaboration, openness, community, accessibility, and sustainability (Castilho & Quandt, 2017). However, these core values may not be visible in some coworking spaces, specifically the collaboration aspect. A relevant aspect of collaboration in coworking spaces is gaining an understanding of individual motivation, expectation, and desire to share resources and interact with one another (Kenline, 2012). “Good neighbours work alone, focusing on their own tasks, politely alongside others; good partners

actively foster the trust required that can lead to formal work collaborations. The good neighbours and good partners proposition suggests there are different levels of collaboration in coworking spaces” (Castilho & Quandt, 2017, p. 33). Similarly, Gandini (2015) discusses that some coworking

spaces’ collaborative practices and interaction amongst members of the community are often incidental. In other words, collaboration and knowledge sharing is a secondary aim or goal within some coworking communities (Gandini, 2015). The assumption of coworking spaces fostering collaboration is not often the case, which Ross and Ressian (2015) also underpin and discuss: “Simply

putting people together in an open office space, therefore, did not guarantee collaboration between its coworker members. However, coworking centres could set up the foundation for collaborative activities if the process were allied to organisational policies that actively supported interactivity amongst the coworking centre members” (Ross & Ressian, 2015, p.52). There is a notion that

coworking spaces often are perceived as just service providers rather than a coworking community, with the potential for collaboration (Seo et al., 2017). This may indicate the inadequate facilitation of collaboration within some coworking spaces as well as the lack of willingness amongst some occupants to collaborate within the coworking community.

1.3 Purpose

This research aims to explore and understand the patterns of inter-organizational collaboration approaches between knowledge professionals such as freelancers, entrepreneurs and start-ups at coworking spaces.

The practical implications of this research will be based on the assumption that by first understanding the inter-organizational collaboration approaches at coworking spaces as well as identifying the occupant types, managers and policy makers at coworking spaces will be able to provide the conditions that foster inter-organizational collaboration amongst occupants. Such conditions could be a platform for skills and knowledge sharing, sitting arrangement and design of the communal space to encourage possible interaction.

Additionally, this research intends to contribute to the understanding of three different occupant types and their collaboration approaches within coworking spaces. In order to achieve this, metaphors were developed by the authors of this thesis to simplify the understanding of the three collaboration approaches associated with the occupant types. This is the novelty of this research, which is a theoretical contribution to the existent literature about the sustainable office phenomena - coworking spaces.

1.4 Research questions

In order to achieve the aim of this research, the following two research questions are proposed. Research question one will address the different collaboration approaches between occupants at coworking spaces. Research question two will address how the coworking spaces as a community can facilitate inter-organizational collaboration.

1. What are the patterns of inter-organizational collaboration approaches between occupants of

coworking spaces?

2. How can coworking spaces foster inter-organizational collaboration?

1.5 Structure of the thesis

This thesis consists of 6 chapters summarized below:

Figure 1., Illustration of the thesis structure

6. Conclusion and managerial implicaUons

5. Discussion

4. Data analysis and main findings

3. Methodology and methods

Case selecUon Data collecUon Philosophical view

2. Key concepts and analyUcal framework

Coworking spaces Inter-organizaUonal collaboraUon Coworking configuraUons Three collaboraUon approaches1. IntroducUon

Background

Introduction, this chapter of the thesis provides background information of the research, research

problem and the aim as well as objectives of this research.

Key concepts and analytical framework, in this chapter the authors of this thesis describes the key

concepts and analytical background of this research to showcase the positioning of this thesis in context to the existent research within this field. Moreover, the key concepts of inter-organizational collaboration and coworking spaces are discussed in-depth, in order to provide an understanding of the analytical framework and tools used as direction in the data analysis.

Methodology and Methods, these two chapters describes philosophical stance of this thesis in the

process of gathering data and the methods used for collecting data. Furthermore, these chapters also provide a justification of the selected methodical choices as well as how the collected data is used in this research study.

Data analysis and main findings, in this particular chapter the findings of the empirical study are

presented and analysed in context to the key concepts and analytical framework.

Discussion, this chapter will provide an extended discussion of the empirical data and analytical

framework in relation to the research topic.

Conclusion and managerial implications, the final chapter will provide the managerial and practical

implications generated by this research study in context to the data findings, key concepts and theoretical concept of shared leadership. Additionally, the conclusion of this research study will specifically answer the research questions and present future research areas.

2. Key concepts and analytical framework

In this chapter, the key concepts and analytical framework will be discussed, these revolve under the umbrella of the sharing economy, however, connected to coworking spaces and inter-organizational collaboration as key concepts. Furthermore, the analytical framework is devised based on theoretical concepts and approaches such as three collaboration approaches and ‘good partners and good neighbours’ configurations, which are chosen to answer the research questions. Moreover, the analytical framework is based on existing thematic literature, such as reviews, journals, articles, research and books on the subject of inter-organizational collaboration, coworking, and coworking spaces, which helped contextualize, justify and refine the aims of this thesis.

2.1. Coworking spaces and inter-organizational collaboration

2.1.1 Coworking spaces

The phenomenon of coworking spaces or the act of occupying a coworking space as a business actor has been referred to by a few authors as the third style of working i.e. coworking spaces do not conform to the idea of a structured traditional workspace where employees are expected to be at their station at certain hours of the day. It (coworking) brought the possibility of envisaging a ‘third way’ of working, halfway between a ‘standard’ work-life within a traditional, well-delimited workplace in a community-like environment, and an independent work life as a freelancer, characteristic of freedom and independence, where the worker is based at home in isolation (Gandini, 2015).

In the same way, sitting in a coworking space is not the same as working from home as a freelancer. Some authors also explored the concept deeper by not only referring to coworking as the third style of working but also categorised as been right in the middle of traditional work style and working from home as illustrated in Figure 2 below. Coworking is a rapidly emerging workplace phenomenon characterised by open-space work environments that lie between working from home and working in a traditional office environment (Ross & Ressia, 2015).

Figure 2: Illustration of coworking centres (spaces) relative to traditional workspaces and working from home, (Ross & Ressia, 2015)

In their effort to shed some light on the work style that involves staying at home, Ross and Ressia, (2015) cited Bailey and Kurland (2002, p. 384) that working from home has often been linked to

teleworking, defined as ‘working outside the conventional workplace and communicating with it by way of telecommunications or computer-based technology. The article further argues that working from home otherwise referred to as virtual communicating or teleworking (telecommunication while working) is a good avenue to contribute to sustainability by way of reducing air pollution originating from employers commutes to and from work. Telework has further been touted as a potential strategy to reduce air pollution and traffic congestion (Bailey & Kurland 2002, p. 384).

One may deduce from the definition of coworking by Uda: “A way of working in which individuals

gather in a place to create value, while sharing information and wisdom by means of communication and cooperating under the conditions of their choices”(Uda, 2013, p.2). There is a great deal of

flexibility and even though the definition suggests that coworking spaces, by default, is an avenue to collaborate, such is not always the case.

A further review by Bouncken and Reuschl (2018) in their article highlighted a few authors’ definitions of coworking spaces as follows: Spinuzzi (2012) explains coworking-spaces by the co-presence of professionals in the same space. Capdevila (2013) highlights the resource sharing and community building among individuals in coworking spaces. Bilandzic and Foth (2013) stress the close interaction between coworking-users (meet, explore, experience, learn, teach, share, discuss). Oldenburg (1989) stresses that coworking-spaces emphasizes on building a ‘Third place’, a working place apart from the classical office and home-office (as cited in Moriset, 2014). As seen in the above brief definitions of coworking spaces, the keywords used namely; community, collaborate, space, sharing, explore and so on further suggests that coworking spaces and its occupants should essentially benefit from the platform provided for collaboration and cooperative work but this cannot be categorically ascertained as being common practice at all coworking spaces (Moriset, 2014).

2.1.2 Inter-organizational collaboration and coworking

A wide yet simple definition of inter-organizational collaboration is that it implies to the process of collaboration between different organizations (Veenswijk & Chisalita, 2011, p. 82). According to Hardy et al. inter-organizational collaboration is defined as “A cooperative, inter-organizational

relationship that is negotiated in an ongoing communicative process, and which relies on neither market nor hierarchical mechanisms of control” (Hardy et al., 2003, p.323). This definition by Hardy

et al. (2003) is a broader perspective on inter-organizational collaboration, whereas Huxhham and Vangen defines inter-organizational collaboration as a process, where involved actors validate problems, create structure and processes for groups, whilst providing solutions by using resources, expertise, and experience provided by the actors from different organizations (Huxham & Vangen, 2005). Similarly, Hardy et al. (2003) argue that a crucial effect of inter-organizational collaboration is within the opportunity to build organizational capacity by transfer or pooling of resources. Furthermore, Hardy et al. (2003) discuss three interrelated effects of inter-organizational collaboration, which are categorized as strategic effects, knowledge creation effects and political effects. Strategic effects is described by Gulati et al. (2000) as an approach to which collaboration supports organizations to further improve their strategic performance through the development of competitive advantage, which is the result of knowledge sharing, the share of resources exchange of know-how etc. (as cited in Hardy et al., 2003). The knowledge creation effect of inter-organizational collaboration is also defined as organizational learning, where Lei and Slocum (1992) describes it as the collaboration between organizations to utilize strategic alliances for learning new knowledge and skills from other alliance partners (as cited in Hardy et al., 2003). In other words, the collaboration is based on learning from other organizations, where the primary aim is to transfer wanted organizational knowledge successfully. Hardy et al. (2003) refer the strategic alliances to ‘networks of collaborating organizations’, which are an essential source of knowledge creation. Lastly, the political effects refer

to the network of which organizations interact and the patterns of relationship between them. In other words, it is described as the inter-organizational network, where more than one collaborative relationship is generated between multiple organizations (Hardy et al., 2003).

Inter-organizational collaboration has various names and can be referred to as strategic alliances, partnerships, networks or joint ventures (Pitsis et al., 2004). The concept of inter-organizational synthesis according to Pitsis et al. (2004) argues that inter-organizational collaboration has various names and can be referred to as strategic alliances, partnerships, networks or joint ventures. Pitsis et al. (2004) discuss the concept of inter-organizational synthesis, which is defined as collaboration and alliances. Moreover, it is argue that synthesis between two organizations arises when the inter-organizational collaboration produces result. In other words, inter-inter-organizational collaboration syntheses (alliances) can facilitate collaboration. According to Pitsis et al., inter-organizational synthesis is argued to be collaboration due to two essential factors; one it refers to interrelations between two organizations and secondly it focuses on the critical aspect of to what extent synthesis is achieved between two organizations. Lastly, stresses that most research within inter-organizational collaboration has a tendency to overlook this important aspect of synthesis in context to inter-organizational collaboration (Pitsis et al., 2004)

Nevertheless, the term inter-organizational collaboration might be perceived as a modern concept (been redefined recent years), however that is not exactly the case as it was defined by Gray as “A

process through which parties who see different aspects of a problem can constructively explore their differences and search for solutions that go beyond their own limited vision of what is possible” (Pitsis

et al., 2004, p.47). Furthermore, Gray (1985) discuss inter-organizational collaboration being an alternative to existing decision processes in organizations, where pooling of external resources such as share of information and multiple stakeholder involvement might provide solutions to problems that organizations cannot solve individually (Gray, 1985). Lastly, Gray (1985) touches upon the topic of inter-organizational domains (network), which is defined as a set of actors such as individuals, groups and organizations that come together due to a shared interest or problem. The inter-organizational domains are argued to be essential for the cross-collaboration between organizations and cutting across the traditional organizational boundaries (Gray, 1985). Nonetheless, Longoria (2005) defines inter-organizational collaboration by drawing parallels between different definitions made by several authors, which are boiled down to four common themes: “ One fundamental nature of collaboration

being a joint activity in a relational system between two organizations, two an intentional planning and design process results in mutually defined and shared organizational goals and objectives, three; structural properties emerge from the relationship between organizations; and four emergent synergistic qualities characterize the process of collaboration” (Longoria, 2005 p. 128). However,

Longoria (2005) discuss inter-organizational collaboration from the critical point of view that the outcome is not necessarily positive. Longoria (2005) further argues that the underlying meaning of inter-organizational collaboration can be vague and unclear, where the outcome of applying this concept is not understood adequately amongst actors in different organizations.

Coworking

Based on the existent literature and research on the concepts of inter-organizational collaboration and coworking, it is evident that there are commonalities between these two concepts. Various authors and researchers have defined the coworking concept, however, what is common is that coworking can be conceptualized to be more than just sharing a physical space. Parrino (2015) quoted the claim made by Jones et al. (2009) that the first person who used the term coworking to describe a place and a way of working was Brad Neuberg, a computer engineer who in 2005 founded the coworking space Hat Factory in San Francisco. In essence, coworking spaces are an avenue to eliminate loneliness and at

the same time enjoy the freedom and flexibility that comes with working in such a relaxed atmosphere.

According to Brad Neuberg who is one of the first individuals to initiate the concept of coworking, defines it as “Coworking is redefining the way we do work. The idea is simple: that independent

professionals and those with workplace flexibility work better together than they do alone“

(coworking.com, n.d.). In other words, coworking is defined as an alternative to overcome the feeling of isolation amongst workers in home offices, traditional offices and coffee shops (Gregg & Lodato, 2018). Similarly, Capdevila (2014) defines coworking as a solution to working alone from home or any other office in a company, where individuals are working in a co-location or physical space. Moreover, Capdevila (2014) draws parallels between coworking and inter-organizational collaboration and stresses: “Coworking is an organizational form that by its own nature facilitates inter-firm

collaboration”(Capdevila, 2014, p.1). Spinuzzi (2012) defines coworking as an informal gathering of

individuals who need to accomplish an objective, task or project, however, desires to work alongside others (Spinuzzi, 2012). Likewise, Deguzman and Tang (2011) discuss coworking concept as dynamics and arrangement of a varied group of individuals that not necessarily work for the same organization or project, however working alongside others sharing resources and space. Kwiatkowski and Buczynski (2011) discuss that coworking provides an approach to be independent and connected with others, however, it is much more than simply sharing a space and facilities (Kwiatkowski & Buczynski, 2011). Gregg and Lodato (2018) argue that coworking has the effect of lightening the burden of risk related to temporary or non-continuing employment due to the sharing of skills and space. Furthermore, they argue that coworking is a solution in states or countries, where such mentioned securities are not provided (Gregg & Lodato, 2018). According to Gregg and Lodato, coworking can be perceived as an ecosystem for ’professional nourishing’, in particular for workers that strive for independence. Evident from existing research and literature, the coworking concept is defined to be the future of work (Gregg & Lodato, 2018). Conclusively this style of working should in no way be confused with co-working (with a hyphen), as it refers to a different term entirely. Gandini (2015) clarifies this bit by citing Fost (2008), this third way was coined ‘coworking’ without the hyphen, to indicate the practice of working individually in a shared environment – and to differentiate it from coworking (with hyphen), which indicates working closely together on a piece of work (Fost, 2008) – although often these terms are used interchangeably.

2.2 Analytical framework

2.2.1 Good neighbours and good partners coworking configurations

Work approach at coworking spaces was further broken down based on contradictions and outcomes by Spinuzzi (2012), whereas some prefer to work parallel, while others expect to work in cooperation. Divided in twofold outcomes, where one is the ‘parallel work as an outcome’ and the second one is ‘cooperative work as an outcome’ (Spinuzzi, 2012). Coworkers that expect to work in parallel want to interact socially with others and gather feedback from those in different industries or fields, building a sort of neighbourly trust, where they figuratively could leave their belongings unattended or discuss business deals without having those details repeated (Spinuzzi, 2012). However, coworkers that expect to work in cooperation often want to gather feedback and learning techniques from fellow-coworkers in their own field, building a working trust that could lead to partnerships (Spinuzzi, 2012).

Moreover, Spinuzzi (2012) refer the two types of outcomes to ‘good neighbours’ and ‘good partners’ configurations. Also known as the good neighbour and good partner patterns, which is illustrated below in Figure 3:

Figure 3: ‘Good Neighbours’ versus ‘Good Partners’ configurations1

As illustrated above, Spinuzzi (2012) defines the ‘good neighbours’ as a coworking configuration, where coworkers (also referred to as occupants) that on regular basis meets with their clients face-to-face also bring their work into the coworking space and work on it in parallel. Moreover, he stresses that this form of collaboration is not emphasised on the individual tasks, however sustaining a neighbourly relationship, where the coworking space can best support all coworker’s parallel work (Spinuzzi, 2012). Evidently, Spinuzzi (2012) draws parallels between neighbours and coworkers, where he discusses the tendency to be unconnected in their work lives, yet show commitment to sharing and improving the communal space. On the other hand, the ‘good partners’ configuration is often emphasizing on team collaboration within the joined workspace (Ross & Ressian, 2015). Spinuzzi (2012) discusses that coworkers within ‘good partner’ configurations often are independent and unaffiliated, however, they are able to link up with other fellow-coworkers to address shared work problems. “These shared problems are the objects of their momentary collaborations, the problems

that individuals from the space are recruited to swarm; the more enduring object, however, is the networking that facilitates these fast-forming instances of cooperative work” (Spinuzzi, 2012, p.17).

Similarly, Ross and Ressian (2015) refer to the ‘good neighbours’ and ‘good partners’ configurations as differentiation between non-collaborative and collaborative environments. Coworking spaces with a ‘good neighbours’ configuration can be perceived as a non-collaborative environment, whereas coworking spaces with ‘good partners’ settings are often a more collaborative environment (Ross & Ressian, 2015). Coworking spaces that have the characteristics of a ‘good partners’ configuration are often reflected in various areas such as the owner’s federated workspace model, coworker’s focus on collaboration and sociality, coworker’s business-service orientation and desire for cooperative work as an outcome (Spinuzzi, 2012). Moreover, coworking spaces that have the characteristics of a ‘good partner’ configuration are also argued to have a sense of community.

A further categorization of these two different approaches was done by Ross and Ressian (2015) and argues that coworking spaces with ‘good neighbours” characteristics can be related to a heterogeneous group of coworkers, whereas ‘good partners’ encompasses a more homogenous community. However, they stress that heterogeneous group of coworkers also are capable of cooperating, where various

coworkers with different professional backgrounds can advise, assist or collaborate with each other (Ross & Ressian, 2015). Nevertheless, Ross and Ressian (2015) also stress that although the ‘good neighbours’ and ‘good partners’ is argued by Spinuzzi (2012) to be divided in this twofold outcome, the coworking spaces can also share both characteristics. In other words, coworking spaces are not necessarily the one or the other, however, can share both features and characteristics of the ‘good neighbours’ and ‘good partner’ configurations. Lastly, a coworking space that exhibits elements of a ‘good neighbours’ setting or configuration is likely to change or shift towards a ‘good partner’ setting due to the change of coworking members and community managers and vice versa (Ross & Ressian, 2015).

2.2.2 Three inter-organizational collaboration approaches

The three inter-organizational collaboration approaches to be discussed in this part was explored by Capdevila (2014), namely; Cost related collaboration, resource-based collaboration and relational collaboration. Firstly, the cost-based collaboration approach’s main goal is based on the reduction of operational or transaction costs, where knowledge sharing and community building is a secondary goal (Castilho & Quandt, 2017). Secondly, the resource-based collaboration approach or level is mainly based on agents being collaborative driven by the need for learning or accessing new knowledge and resources (Capdevila, 2014). In other words, it is also about a combination of personal convenience and socialization advantages (Castilho & Quandt, 2017). Moreover, Capdevila (2014) argues that in order to engage in a resource-based collaboration type of approach, occupants (coworkers) are required to be acquainted with the skills and resources they do not possess and wish to complement with their own. Therefore, as a collaborative activity, it is required that the occupants (coworkers) are able to ‘scan’ the resources available within the collaborative community in order to find partners that possess complementary resources (Capdevila, 2014). Lastly, third collaboration level is the relational collaboration approach, which mainly is based on occupants (coworkers) engaging in collaboration to find synergistic results and investing actively in the community building dynamics (Capdevila, 2014).

In essence, one may argue that the cost-related collaboration approach is of a selfish nature on the part of the coworking space occupant while the relational collaboration approach is evident of a selfless approach i.e. occupants put the coworking community first in their collaboration approach. The resource-based collaboration can be seen as neutral to the coworking space community due to the fact that occupants in this category engage in knowledge and resource sharing to fill a gap while at the same time integrating resources into the community by way of contribution - a give and take scenario.

Cost-related collaboration

There are several factors that may be responsible for an occupant’s decision to collaborate. Capdevila (2014) argues that apart from the socialization aspect, some occupants (coworkers) are motivated to collaborate based on cost reduction. When new start-ups or occupants (coworkers) chooses to work in a coworking space it can be perceived as a reason to reduce operational costs (WIFI, coffee, electricity, office space etc.), however it might also lead to a cost reduction for the existing start-ups and occupants (coworkers) (Capdevila, 2014). Moreover, Capdevila (2014) stresses that the cost reductions are not solely economic savings in relation to sharing a space or facilities, yet reducing transaction costs related to proximity to fellow community members within the coworking space. Spinuzzi (2012) and Capdevila (2014) both similarly argue that socialization, personal convenience

and cost reductions might often be the driven factors of collaboration amongst occupants (coworkers) within coworking spaces.

Furthermore, occupants are not solely working at coworking spaces to just substitute the traditional offices and reduce general costs, there is also the possibility of interacting and socializing with fellow occupants, which might reduce the costs in relation to gaining information, knowledge sharing, advisory feedback or reaching contractual agreements. The proximity to fellow occupants of the coworking community can reduce transaction costs in relation to collaboration (Capdevila, 2014). In other words, working closely within coworking spaces also enables the reduction of transaction costs in the process of seeking new collaborators or partnerships.

Resource-based collaboration

In resource-based collaboration, occupants are often motivated to collaborate, in order to engage in knowledge sharing. Some of the underlying elements can be to learn and improve their own skills, capabilities and resources (Capdevila, 2014). As well as the motivational factor to engage in collaboration to achieve access to complementary sources that they do not possess (Capdevila, 2014). From an occupant (coworker) perspective, this can be done by several collaborative practices such as participating in activities such as networking or social events in the search for resources in order to learn and integrate with their own resources and professional capabilities. Capdevila (2014) describes this kind of activity as learning or coaching activities.

Furthermore, these activities are pivotal for building the community within the coworking space. Additionally, it will allow the occupants (coworkers) to gain new knowledge and resources as well as the opportunity to form potential collaborations (Capdevila, 2014). According to Boschma (2015), the environments have a crucial role in facilitating various types of proximity among the coworking members, were ensuring a common set of values, interest or professional domain might enable collaboration (Capdevila, 2014). Similarly, Capdevila (2014) argues that events (social or networking) might attract coworking members with similar interests, which might further strengthen and build the community within coworking spaces. Additionally, he underlines the important role of coworking spaces managers (community manager) in facilitating collaboration amongst coworkers. Coworking spaces managers are also required to support (providing coaching) coworking members in developing collaborative skills and connecting them to new opportunities of collaboration, this type of collaborative practice can be facilitated through coaching activities or group meetings (Capdevila, 2014). According to Capdevila, the distinguish between cost-related and resource-based collaboration is that the first collaboration (cost-related) approach often is motivated by the self-interest of filling a resource gap in relation to a project. In contrary, resource-based collaboration often tends to occur when the aim is to develop a new project, product or service by combining different resources from a group of coworking members. In other words, this is a collaborative practice that facilitates the process of integrating and coordinating resources between occupants (coworkers) (Capdevila, 2014).

Relational collaboration

In relational collaboration exploring rather than exploiting is often the motivational factor for occupants (coworkers). Capdevila (2014) argues that they are not motivated by the extrinsic yet intrinsic motivation. In order words, external factors such as financial elements or cost reductions are not primary motivational factors. Occupants (coworkers) tend to engage in collaborative practices based on creating new knowledge and gaining new resources (Capdevila, 2014). However it differs from resource-based collaboration, where relational focuses on community building and the idea of exploring collaboration rather than exploiting to gain knowledge or resources they lack. Occupants

can often identify with the community and they focus on collaborative success of fellow occupants (coworkers) and the coworking space (Capdevila, 2014). According to Capdevila, many coworking spaces foster collaboration, however he stresses that: “Most coworking spaces foster collaboration by

seeking to put in contact different and complementary resources and knowledge bases. Co-location is however not a sufficient condition. In order to facilitate knowledge sharing and fruitful communication, agents have to have the sufficient absorptive capacity to be able to recognize, assimilate and apply new knowledge from an external source”(Capdevila, 2014, p.17). Some

coworking spaces focuses on specializing in a particular field, which might attract like-minded individuals or coworkers that has similar views. For example a coworking space that focuses on developing a highly collaborative community will possibly not be keen to attract all kinds of occupants (coworkers), specifically ones that are motivated by cost-related collaboration (Capdevila, 2014). Another important element to relational collaboration is transmitting a vision, which reflects on the community of the coworking space. As pointed out in the above-mentioned example, coworking spaces that focus on creating a highly collaborative community, the environment or community managers often transfer this vision to the coworking space. From a coworker perspective, this might strengthen the feeling of community and collective identity (Capdevila, 2014). Capdevila (2014) argues that this might encourage coworkers of the community to initiate ownership of the space and help empowering the community. Furthermore, Capdevila stresses that relational collaboration do not emphasis on the resources shared by individuals of coworking spaces, however it is based on the synergistic effect of collaboration. In other words, the collaborative practices in a relational collaboration are derived by the principle that the outcome of collaboration and community is prioritized higher than the individuals collaborating (Capdevila, 2014).

Lastly, Capdevila stresses that coworking members will search for coworking spaces that fulfil their needs in relation to their collaboration approach. Illustrated below in Figure 4 are Capdevila’s three collaboration approaches in context to Castilho and Quandt’s (2017) types of coworking spaces:

Figure 4: Three collaboration approaches’ interrelation to community building and convenience sharing types of coworking spaces 2

2 Source: Inspired and developed from Spinuzzi (2012) and Castilho & Quandt (2017)

Empowering the community Transmi4ng an inspiring vision Focusing on a specializa9on Integra9ng resources Providing coaching Par9cpa9ng in knowledge sharing Dynamizing the community Reducing transac9on costs Reducing opera9onal costs Cost-related Collaboration Resource-based Collaboration Relational Collaboration Community Building Convenience Sharing Convenience Sharing

Similarly, Castilho and Quandt (2017) discuss a two-fold coworking space typology, where one type is the convenience sharing coworking space and second is a community building coworking space. “Convenience Sharing coworking spaces are mostly related to knowledge sharing and supporting a

collective action towards an effective execution, whereas Community Building coworking spaces are more related to enhancing a creative field and enhancing an individual action for the collective”

(Castilho & Quandt, 2017, p. 41). Castilho and Quandt (2017) draw parallels to Capdevila’s theory of three collaboration approaches. Specifically, relational collaboration is argued to be more evident in types of coworking spaces that emphasises on community building and team vision. However, resource-based and cost-related collaboration approaches are argued to be associated with convenience sharing coworking spaces, where the focus is mainly on collective actions such as knowledge sharing or effective use of resources and space (Castilho & Quandt, 2017).

Castilho and Quandt (2017) discuss the commonalities between convenience sharing type of coworking spaces and the resource-based collaboration approach by Capdevila (2014). According to Castilho and Quandt (2017) in convenience sharing type of coworking spaces there tends to a focus on self-interest, however with a collective view that is not adopted adequately. Similar to the resource approach, convenience sharing coworking spaces facilitate socialization advantages and personal convenience, which some coworking members are attracted to. In other words, conveniences sharing coworking spaces are often associated with knowledge sharing and support of collective action towards effective implementation (Castilho & Quandt, 2017). Nevertheless, in community building type of coworking spaces, collaboration relationships amongst coworkers is mainly built on trust and formal commitment. Similar to Capdevila’s relational collaboration, the focus is on encouraging and improving individual actions for the collective (community). Moreover, Castilho and Quandt (2017) argue that community building coworking spaces create interdependence and formal commitments, which is developed from selflessness and self-sufficiency.

2.2.3 Three occupant types as metaphors

The authors of this thesis have developed three insect metaphors, which were inspired by the work of Spinuzzi (2012) that focuses on the ‘good neighbours’ and ‘good partners’ configurations (patterns). The metaphors were developed based on the communication that took place between the authors of this thesis and the selected interviewees. The perception based of the interview transcripts also contributed to the metaphor categorization. In light of this, it is important to stress that these metaphors should not be used to generalize occupants at coworking spaces without prior communication between community managers and prospective occupants. The metaphors can also support in the understanding of the patterns of inter-organizational collaboration.

The section will elaborate on the insect metaphors used in the matrix of the correlation between occupant types and collaboration approaches. In the course of the analysis, three different analytical bases will be considered i.e. interview response versus occupant types (metaphors), Interview response versus collaboration approaches and lastly a matrix that combines both the occupant types and the correlation to collaboration approaches based on the findings from this research.

Insects as metaphors to understand collaboration patterns among occupants

The use of insects as metaphors in presenting the data gathered from this study was informed by the need to simplify the findings. Carpenter (2008) quoted Patton, (1990) as such - metaphors function as one creative strategy that enables researchers to analyse and interpret data adequately. The traits of the

animals chosen to categorize the interviewees and their work approach will further illuminate the concept and style of collaboration exhibited by the occupants in question. Researchers can employ metaphors as a mechanism to structure data or to help the researcher understand a familiar process in a new light (Carpenter, 2008). To further emphasize the reason why the authors of this thesis have chosen to use metaphors as one of the tools of the analytical framework, Carpenter (2008) argues that metaphors have the potential to deepen the understanding of phenomena, generating new insights and challenging old perceptions. The matrix above represents how the interviewees are categorized based on the different insect characteristics that correlate to their work style and collaboration approach. The insects used in the course of this analysis are Bumblebees, Fireflies and Amazonian Ants.

Bumblebees - Bombus species

From most of the literature reviewed, the common characteristic of bumblebees that fits the purpose of this research is the insects’ electric navigation ability. Zakon (2016) quoted the study carried out by Clarke et al. (2013) that showed that flowers have distinct patterns of electric charge over their surface and that bees learn to discriminate between charged and uncharged flowers. As such, bumblebees are able to identify specific flowers from the other. Zakon (2016) further claims that Clarke et al. (2013) hypothesized that a bee might use the net charge of a flower to judge if the flower has been recently visited by another bee and, therefore, has diminished offerings of nectar and pollen. Bumblebees can actually sense the minute electrical field created by flowers, and use it to decide which flowers would have the best nectar (Handley, 2013).

A characteristic with this level of accuracy and being instinctive can then be said to be similar to that of the occupant work approach at coworking spaces that tend to proactively explore opportunities for collaboration at all times. These occupants are usually the proactive and keen extroverts who tend to sense minute opportunities where no one else will. The Bumblebee occupants of coworking spaces tend to have a high level of sensitivity to viable leads and collaboration opportunities.

Fireflies – Photuris species

Fireflies light up to attract mates of the opposite sex. Males and females of different species flash unique patterns to let potential partners know they are available and interested in mating (Velcoff, 2013). If you were to watch the light show from the beginning, you would see it start with just a handful of fireflies, which found the right rhythm (Handley, 2013).

In likening this insect trait to occupants of coworking spaces, the deduction is that certain individuals, although highly receptive to the idea and actual process of collaborating, they won’t necessarily go out of their way to seek the opportunity. The Firefly occupants of coworking spaces are usually introverts who tend to keep to themselves yet at the same time give off subtle signals to indicate their interest to collaborate. This is sometimes done by posting something online in the community’s group page or putting a poster on the notice board but nothing more. They usually will not carry out any elaborate action or gesture to proactively seek collaboration as in the case of the Bumblebee occupants.

Ants - Formicidae species

Ants live and work together in communities and an ant community is called a colony (Datt & Gopalakrishna, 2013). In this case, one will refer to coworking spaces as a colony. The colony’s efficient behaviour emerges from their ability to self-manage individually and their ability to carry out complementary work activities simultaneously in groups, in unison and free from the delays associated with hierarchy (Datt & Gopalakrishna, 2013). The individuals that are able to put the colony first and operate in a very selfless manner will fit this category. The Ant occupants at

coworking spaces tend to focus on building the colony – the community, they are the bridge builders, facilitating collaboration at all levels. They help facilitate collaboration for the benefit of others even when they do not necessarily benefit from the said collaboration. The advancement of the coworking community and the success of the fellow occupants tend to be the priority of the Ant occupants. While the above categorization is meant to simplify the findings of this research, it is noteworthy that some of the interviewed occupants of the coworking spaces in question will exhibit traits of more than one insect. In essence, the above categorisation should not be seen as a final basis for categorising the individuals in question but rather it should serve as a guide to understand some of the personality types and work approaches of the occupants relative to their willingness to collaborate or lack thereof.

Illustrated below is the matrix table 1, which is developed by the authors of this thesis and inspired by Capdevila’s (2014) three collaboration approaches.

Collaboration approaches

Occupant types Cost-related (Negative impact on the coworking community) Resource-based (Neutral impact on the coworking community) Relational (Positive impact on the coworking community) Bumblebee occupants (Proactive, Extroverted, partner relationships, self-interest) X X Firefly occupants (Non-active, Introverted, Neighbourly relationships, welcoming) X Ant occupants (sharing both collaboration patterns, community relationships, selfless, bridge-builders, proactive) X3. Methodology and methods

In the following chapter the authors of this thesis will justify the methodological choices used in the research and the philosophical stance.

3.1 Philosophical view

This section aims to specify the stance in the science of philosophy used in this thesis.

The ontology and epistemology refer to the philosophy of science, which encompasses the beliefs or assumptions of the reality (ontology) and the acquisition of knowledge and relationship between research participant and researcher (epistemology)(6 & Bellamy, 2012).

Therefore, the approached used in this research paper is based on an ontological position referred to as constructivism, where knowledge is constructed through interaction with other people (personal experience (6 & Bellamy, 2012). This approach is found compatible with the subject of coworking spaces and inter-organizational collaboration patterns, as the occupants’ perspective and personal experience on the topic was the basis of the findings of this research.

The authors of this thesis are aware that there is a possibility for interpretations and deductions to vary as regards data, knowledge and the additional information provided in this academic paper due to individual differences and multiple perspectives. “Social work values hold that human knowledge is

never final or absolute, as does constructivism”(Rodwell, 1998,p.4).

3.2 Qualitative research

The methodological approach used in this thesis is qualitative research, furthermore, it is an inductive approach that seeks to understand meaning through research questions, theoretical concepts and interpretation of primary raw data (Thomas, 2003). Specifically, the research study observed the patterns of inter-organizational collaboration in the data and emerged existing theories(Capdevila and Spinuzzi) to develop a matrix with metaphors for three occupant types. Moreover, the social science used, as methodological strategy is exploratory research, which is about exploring a certain phenomenon, without having an adequate scientific knowledge about the topic, however exploring it, is worth the study. “The outcome of these procedures and the main goal of the exploratory research is

the production of inductively derived generalizations about the group, process, activity, or situation under study”(Given, 2008, p. 328). Both the exploratory and inductive approaches are considered

important when revealing new ideas, knowledge or observations that could not have been achieved solely through a deductive approach (Given, 2008).

Throughout the research, the authors have developed themes and categories from the raw data, which support the research aim and questions, moreover, some of the interpretations of the data have shaped the research design. The thesis’ key concepts and analytical framework within the topic of collaboration patterns in coworking spaces, were collected and interpreted before the collection of empirical data, due to the reason that the authors needed relevant literature that could shape the research questions. Furthermore, from the themes in the data gathered the authors of this thesis, identified and developed three occupant types in relation to collaboration approaches.

Nonetheless, the selection of the topic of collaboration patterns in coworking spaces was derived due to one of the author’s one year experience working within a coworking space, where the author as an occupant (coworker) gained first- hand knowledge about this ‘sustainable office phenomena’.

3.2.1 Case selection

In this chapter, the authors of this thesis will briefly introduce the selected cases of coworking spaces located in Malmö and their accessibility, which is based on the authors’ own observations and the coworking spaces’ informative websites. Furthermore, it is important to stress that the three respective cases, where strategically chosen due to its accessibility and close relations to the student network of Malmö University. The authors of this thesis did reach out to other coworking spaces located in Malmö (e.g. to name a few House of Ada Coworking, From Studio Coworking), however, the community manager’s were unfortunately not responsive. Also important to stress that the three respective cases are not necessarily generally representative for coworking spaces in Malmö, as each of them separately is different.

Minc

Minc is a coworking space developed in 2002, located in the City of Malmö close to public transportation. Minc as a coworking space provides different services such as an incubator programme, accelerator fast-track programme and a shared space start-up lab for entrepreneurs, freelancers and start-ups businesses. They pride themselves on many success-stories of start-ups developing through the Minc house to become renowned and innovative businesses in Scandinavia (Minc website, 2018). Minc as a coworking space community is figuratively a larger community and building, where on the first floor there is an open space (start-up lab) free of charge for occupants. Moreover, on the second floor there is the fast-track accelerator space, where occupants have applied and are part of a six months programme. The third floor, there is a combination of occupants renting space (closed office space) and occupants part of the incubator programme. The design of the coworking space community in Minc has a sense of three different design environments an open space, closed space and communal space. Evident from the number of interviews conducted with occupants from Minc, the accessibility to this particular coworking space has been less challenging and the community manager, as well as occupants, were quite responsive and approachable. The interviews scheduled and conducted at Minc were a combination of drop-ins and pre-scheduled meetings through email and Facebook correspondence. Conclusively Minc as a coworking space is a bigger community, hence a better accessibility.

Stpln

Stpln (pronounced Stapln) is a coworking space community, which provides shared workspace and incubator programme for creative entrepreneurs and projects. It is located in the city of Malmö near dry-dock, housed in a former old slipway (Stpln website, n.d.). Stpln is a smaller community, however with great and flexible space for different workshops and events. The design of Stpln is an open space environment, wherein the far-sided corner is occupants that rents space for a fixed price and the close side is a free space for entrepreneurs, freelancers and so forth. There are also a few communal spaces for the occupants of the building. Stpln as a coworking space is also known to be a great community for creative individuals. The accessibility to occupants of Stpln has been a bit challenging due to the