BACHELOR DEGREE PROJECT THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15hp

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Management

AUTHORS: Julia Krajka, Matilda Gustafsson, Victor José Vallim da Silva

Seven Different Countries,

Seven Different Festivals,

One Brand

Bachelor Thesis Degree Project in Business Administration

Title: Seven Different Countries, Seven Different Festivals, One Brand - A Global MusicFestival’s Adaptiveness and Globalness

Authors: Matilda Gustafsson, Julia Krajka, Victor José Vallim da Silva Tutor: MaxMikael Wilde Björling

Examiner: Anders Melander Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Globalization, Localization, Music Festival, Adaptations, Customer Perceptions.

Abstract

Background: Globalization and localization are constantly clashing, collapsing, and transforming

one another, and many studies have investigated how various global companies deal with the balance in between these two opposite strategies. However, little does research reveal about how music festivals adapt and operate using globalization or localization in the global market. Further, studies have shown that the globalness of a brand adds value for customers, but this effect has not been investigated in the global music festival industry.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to deep understand a global music festival’s adaptiveness and how its adaptations are perceived by its attendees from different countries. Further, this study also aims to analyze how the globalness of a music festival affects and influences its attendees.

Method: A case study focusing on the music festival Lollapalooza and its editions in Brazil and Sweden. The study follows a deductive approach using a mixed-method by collecting both quantitative and qualitative data. An online survey, interviews, and an email questionnaire are the main primary sources of data collection.

Conclusion: The results show that adaptations are important for attendees as well as for the

festival itself. Many adaptations were noticed by attendees, but it is still unsure what other ‘’invisible adaptations’’ were done in order to meet the market demands. The globalness of the festival makes customers assign additional positive attributes to the festival brand, while also local adaptations such as food, beverages, and artists were appreciated by the attendees. Thus, it appears that some aspects of a music festival should be globalized, while others should be localized, or that even glocalization should be utilized in global music festivals. To conclude, festival’s managers can use the findings to better understand that global cues can be used to raise the brand value of a festival, but more importantly, that globalization and localization should be applied in different aspects of a festival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to show our appreciation to the participants of this study for the time given and all the valuable information provided that were crucial to answer the proposed research questions. We are truly thankful and acknowledge them for their extended efforts, specially the participants who made themselves available for the interviews.

Secondly, we would like to thank our tutor MaxMikael Wilde Björling for the time given to support us, as well as invaluable feedback provided during the seminars even outside of class.

Thirdly, we would like to thank ‘Maria Silva’ (fictitiously represented due to anonymity) for the support and time spent during the past months in order to help us conducting this study.

Lastly, we would like to show our gratitude towards the seminar groups who also contributed to this thesis by giving us continuous feedback during the entire writing process. Finally, thanks to Anders Melander, the course examiner, who instructed and guided us with writing this thesis.

_____________________ _____________________ _____________________ Julia Krajka Matilda Gustafsson Victor José Vallim da Silva

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. BACKGROUND 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2. Problem Discussion 7 1.3. Purpose Statement 8 1.3.1 Research Questions 8 1.3.2 Delimitations 8 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 9 2.1 Music Festivals 92.1.1 Attendees Motivations and Participations 9

2.1.2 Customer participation 10

2.2 Globalization & Localization 10

2.3 Brands & Global Brands 11

2.4 Positioning Strategies 13

2.5 Market Orientation and Adaptations 13

2.6 Cultural Values 14

2.6.1 The Hofstede Dimensions 15

2.6.1.1 Brazil and Sweden 16

3. METHODOLOGY & METHODS 17

3.1 Methodology 17

3.1.1 Research Philosophy and Paradigm 17

3.1.2 Research Approach 18 3.1.3 Research Strategy 18 3.2 Method 18 3.2.1 Data Collection 18 3.2.1.1 Secondary Sources 19 3.2.1.1.1 Literature Search 19 3.2.1.2 Primary Data 19 3.2.1.2.1 Electronic Survey 19 3.2.1.2.2 Interviews 20 3.2.1.2.3 Email Questionnaire 21

3.2.2 Population and Sampling 21

3.2.3 Data Analysis 22

3.2.4 Data Quality 23

4. EMPIRICAL FINDINGS 26

4.1 Survey 26

4.1.1 Age Group and Gender 26

4.1.2 Preferences about the type of festival to attend 27

4.1.3 Perception about Lollapalooza 28

4.1.5 Attendance behavior in Brazil 32

4.1.6 Getting to know Lollapalooza 33

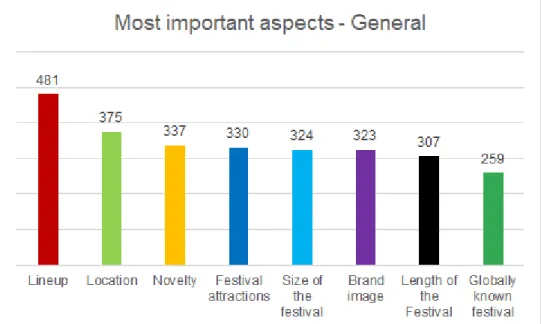

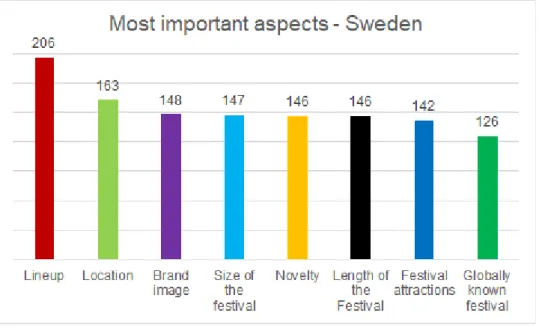

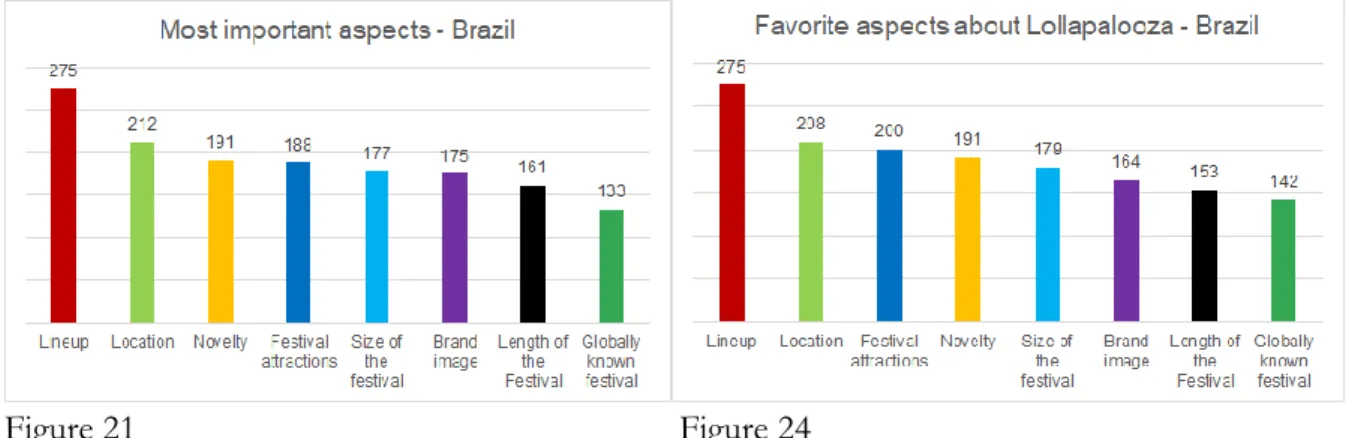

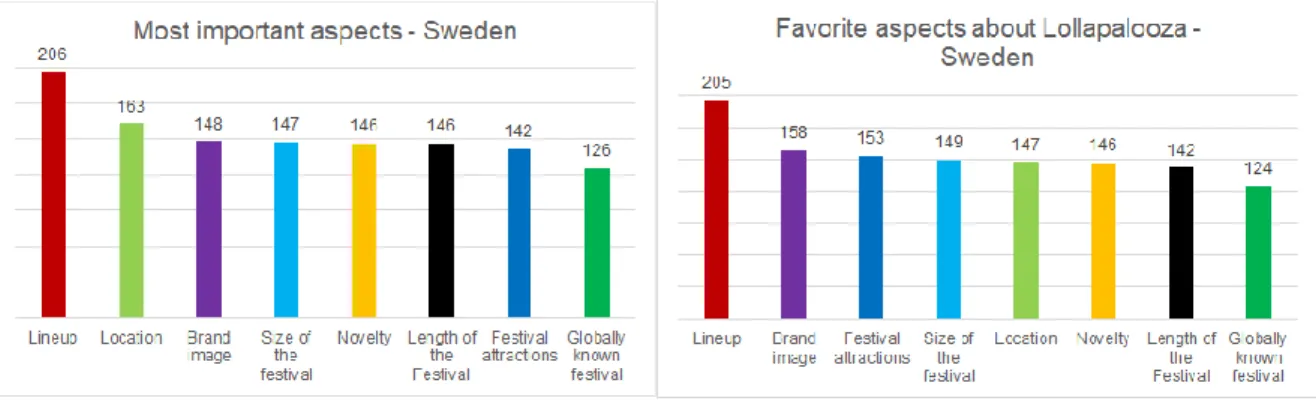

4.1.7 Most important aspects when choosing a music festival 36

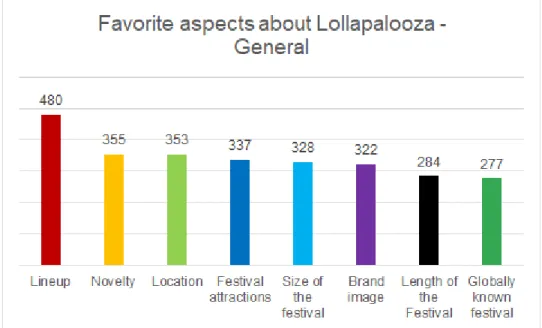

4.1.8 Favorite aspects about Lollapalooza 38

4.1.9 Aspects that Lollapalooza is better than other festivals 41 4.1.10 Aspects that Lollapalooza is worse than other festivals 43

4.1.11 Open-ended Question 1 44 4.1.12 Open-ended Question 2 45 4.1.13 Open-ended Question 3 46 4.2 Interviews 47 4.2.1 Question 1 47 4.2.2 Question 2 48 4.2.3 Question 3 48 4.2.4 Question 4 49 4.2.5 Question 5 50 4.2.6 Question 6 50 4.2.7 Question 7 51 4.2.8 Question 8 51 4.2.9 Question 9 51 4.2.10 Question 10 52 4.2.11 Question 11 52

4.2.12 Question 12 - Extra Question 52

4.3 Email Questionnaire 53

5. ANALYSIS 54

5.1 Global Brands 54

5.2 The Positioning Strategy Framework & Global and Local Cues 54

5.3 Perceived Globalness 56

5.4 Culture 56

5.5 Motivations and Important Aspects 57

5.6 Adaptations 58

5.7 Customer Participation 59

6. CONCLUSION 61

7. DISCUSSION 62

7.1 Practical Implications and Contributions 62

7.2 Limitations 62

7.3 Future Research 62

8. REFERENCES 64

9. APPENDICES 71

Appendix C - E-mail Questionnaire 83 Appendix D - T-test ‘Most important aspects when choosing a music festival’ 84 Appendix E - T-test ‘Favorite aspects about Lollapalooza’ 85

1. BACKGROUND

___________________________________________________________________________

In this section, an introduction of the research problem is presented, followed by a short discussion of the problem, its relevance and purpose, along with the research questions.

___________________________________________________________________________

1.1 Introduction

There are many studied cases of global brands within International Management research. These companies are able to adapt their offerings to meet diverse customer needs and expectations while also sustaining a strong and consistent global brand image. Since markets and cultures differ from each other, it seems that there is no right or standard choice between localization and globalization that creates the perfect mix. Instead, every case is different from each other, and many factors are involved in this type of decision, such as market size, economic environment, cultural differences, among others. Classic global companies and brands that offer tangible products, such as Starbucks and IKEA, have distinct ways of operating and are both considered to be successful. There is relevant and extended research done within these and many other global brands, as well as their strategies.

It has been found that additional positive attributes are addressed to global brands just because of their globalness (Gammoh, Koh & Okoroafo, 2011; Steenkamp, Batra & Alden, 2002). However, little has been discussed about global music festivals, their adaptations in the global market, and their effect of globalness. This is surprising since the market for festivals is not new. In fact, literature states that the first music festival, the Three Choirs Festival, dates back as far as to 1724 (Çakici & Yilmaz, 2017), and it is a market that, along with the experience economy and events market, is growing (Getz, Andersson & Carlsen, 2010).

As this market becomes more crowded, the competition increases, and thus festival managers should be increasingly interested in strengthening their brand and finding new sources of competitive advantage in order to survive. Especially since current research points out that imitation of festivals in different locations is common, but very few festivals understand the importance of ‘’[...]the core values of their festival that could provide the unique selling point and the basis for differentiation and competitive advantage.‘’ (Carlsen, Andersson, Ali-Knight, Jaeger & Taylor, 2010, p. 129). Additionally, global brands are growing across the world, but cultures are not expected to converge (Samiee, 2019). Rather, consumer behavior is tended to become more heterogeneous because of cultural differences (De Mooij & Hofstede, 2002).

One global music festival that operates in distinctive different markets, with different cultures across the globe, is Lollapalooza. The music festival started in 1991 and today it features rock, alternative rock, hip-hop, and techno music playing annually in the United States, Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Germany, France, and Sweden.

1.2. Problem Discussion

Getz et al., (2010) argue that the social-cultural constructs, festivals, have a somewhat vague definition in the existing literature, as well as a broad meaning. This is because festivals come in various forms and may have different meanings across nations, and their definitions are often misapplied which in some cases can lead to confusion.

Although not clearly defined, festivals must be viewed differently than other events mostly because of their focus on celebration, while other planned events might focus on entertainment, politics, education, competition, and other cores. Based on the core of the celebration, festivals also bring many cultural and social dimensions such as rituals and symbolisms (Getz et al., 2010).

As recognized by Carlsen et al., (2010), many festivals duplicate their concept in different locations without any further innovative adaptation. On the other hand, more entrepreneurial festivals often create value, bring innovation, and seize more market opportunities (Getz et al, 2010). Further, the increase in the amount of individuals attending different festivals each year has led to even more of these events in the market, and thus problems with competition among them (Hoksbergen & Insch, 2016; Leenders, van Telgen, Gemser, van der Wurff, 2005; Çakici & Yilmaz, 2017). Thus, festivals need to recognize the importance of understanding their unique competing factors in order to set and sustain their position in the market (Carlsen et al., 2010).

One of the growing types of festivals is the music festivals, which Leenders (2010) describes as generally outdoor music-oriented events with live performances, food stations, extra attractions, and social activities. Live music entertainment and food and beverages have also been pointed out by Getz et al. (2010) as the main two factors that keep festivals consistent across markets.

Çakici and Yilmaz (2017) recognized four main motivational factors of attendees of a music festival: Novelty, Socialization, Escape, and Family. They also recognized that understanding these motivations is essential for a festival management in terms of planning and organizing these events. Manthiou, Kang & Schrier (2014) argued that, by getting to know an organization and having a positive opinion about their brand image, people tend to become loyal and attend an event based on their previous experience. However, Nicholson & Pearce (2001) concluded that people usually go to these events based on the offers instead of just because of brand recognition.

While partnerships and networks could be key innovative strategies for music festivals, there is not much evidence that indicates partnerships between music festivals and destination management organizations. This can be considered as a threat for future festivals since the compatibility between the global brand and the local cultural elements improves customers’ opinions about the brand’s local icons and can increase ticket sales (He & Wang, 2017).

To conclude, it is relevant and needed to acquire more research and knowledge on global music festivals adaptiveness to different markets and cultures, as well as how these adaptations are perceived and evaluated by their attendees. Getz et al. (2010) have suggested that a cross-cultural comparison can bring great learnings in how festivals work in different countries and that theories such as Hofstede’s dimensions may help to explain the possible cultural differences between music festivals. This subject has been studied in other contexts and industries, but not in the global music

festival industry. Further, it is also relevant to analyze the effects of the globalness of a global music festival on attendees’ perceptions and evaluations, since this matter has also been understudied.

1.3. Purpose Statement

The concept of global music festivals is growing, but there are many unanswered questions and a gap in research of global music festivals and their adaptations to different markets around the world.

The purpose of this study is to analyze how a global music festival adapts its offerings in different markets and how these adaptations are perceived and valued by its attendees. Furthermore, the research team wants to investigate the globalness of a global music festival brand and its effects on attendees’ evaluations and perceptions, such as, if its globalness has positive effects on the music festival’s brand image, as theory suggests.

The intention is to gather information from participants of the music festival 'Lollapalooza' both in Brazil and in Sweden to deeper understand their experiences at the festival.

1.3.1 Research Questions

(1) What is the adaptiveness of a global music festival and how are these adaptations perceived and valued

by its attendees?

(2) How is the globalness of a global music festival being valued and influencing attendees?

1.3.2 Delimitations

The study focuses on the music festival ‘Lollapalooza’ and only on its editions in Brazil and Sweden, due to their distinctive differences in culture. Additionally, participants of this study were only native attendees from these two countries.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

___________________________________________________________________________

The purpose of this section is to provide the theoretical background of the topic and give an introductory understanding of the general and central concepts of this study.

___________________________________________________________________________

2.1 Music Festivals

A festival can be defined as a public celebration (Getz, 2005) where people share their interests with others through different activities (Saleh & Ryan, 1993), while Pavluković, Armenski, & Alcántara-Pilar (2017) also consider it as an opportunity of new social and cultural experiences. Furthermore, music is considered as ‘’the universal language of celebration and entertainment’’ (Getz, Andersson & Carlsen, 2010, p. 38). Individuals have been using music as a way of expressing their identities and values (Ballantyne, Ballantyne & Packer, 2014) but specifically, young people have been treating music as a ‘’badge of identity’’ (North & Hargreaves, 1999). By connecting these two definitions, a music festival is an outdoor event with live music performances, and extra entertainment for attendees (Leenders, 2010).

Nordvall & Heldt (2017) have found correlations between competition, adaptiveness, and failure. Based on these findings, they stated that awareness and ability to adapt to the changes in the environment are significant to be successful since young festivals that are more efficient can replace older festivals that do not fully adapt to the market or cannot compromise when it is needed. Carlsen at al., (2010) also specified that to prevent failure, awareness of competition and innovation should be considered in the organization’s strategy. Since the competition among music festivals increases, causing many festivals to fail, understanding its participants’ motivations is essential when planning the events (Çakici & Yilmaz, 2017).

2.1.1 Attendees Motivations and Participations

Nicholson and Pearce (2001) studied participants’ main motives for attending festivals by examining five different types of events, one of them being a music festival. In the music festival, ‘Excitement’, ‘The ability to see entertainment’ and ‘To be with people that share similar interest’ were found to be the most listed motivations for attendees. Additionally, ‘Socialization’ was an important motivator for all attendees of the five festivals.

Çakici and Yilmaz (2017) found that the main motivations for attending a music festival were: ‘Novelty’, ‘Socialization’, ‘Escape’, and ‘Family’. These motivations have also been recognized by previous authors in similar studies. Uysal, Gahan, and Martin (1993) and Mohr, Backman, Gahan, and Backman (1993) also found a fifth motivation in their studies, being ‘Excitement’.

Further, Hoksbergen and Insch (2016) found that the main reasons for individuals to attend a festival are firstly ‘Spend time with friends’, and secondly ‘Music performances.’ However, for the repeat festival attendees, ‘Music performances’ - the lineups - become the most relevant reason.

This shows that motivations for attending a festival differ depending on previous festival experiences.

2.1.2 Customer participation

Customer participation is related to customers being involved in producing and later delivering the service through which they gain new experiences, which leads to an increase in the value of experience (Ippolito, 2009). Lanier and Hampton (2008) stated that customer participation in a value creation process changes depending on which stage of the fantasy cycle of the festival that customers are. The fantasy cycle consists of five stages: creating stage, raising stage, sustaining stage, decline stage, and terminus stage. Looking at the creation stage, consumer involvement is low since in the beginning, they learn about the festival and create their fantasies about it. Here, they usually engage by collecting resources given by producers which do not require big commitment from their side. In the raising stage, since customers initiate working on improving the fantasy engagement of their participation, the experience starts to grow. This leads to the consumers’ engagement using resources that require greater investments. In the third, sustaining stage, consumers engage through resources that involve time, energy, or money that now are mainly under their control. In the decline stage, customers try to operate with producers or other customers to change some aspects of the festival for the purpose of creating new resources to sustain their involvement. In the last, terminus stage, customers are looking to get their fantasies pleased again.

Lanier and Hampton (2008) concluded that consumer participation often changes over time as a result of the development and involvement of the consumer’s fantasy. Festivals’ participants develop their fantasies and engage in their experience in new ways by different types of engagements in each stage.

2.2 Globalization & Localization

Globalization is considered a highly old phenomenon. It may be defined as cultural, economic, social, and political connections and exchanges between people in different geographical areas (MacEwan, 2001). However, from a business perspective, Danos and Measelle (1990) define globalization as businesses operating across national boundaries in several markets by either selling their goods or services and/or competing for production inputs in these markets. Additionally, the authors argued that a firm can be global to a more or lesser extent and that a firm is completely global if ‘’[...] its markets traverse all national boundaries’’ (p. 77) and thus competition or customers can come from anywhere around the globe. Already back then, the authors predicted that globalization would accelerate in most markets and thus most businesses must carefully consider this concept moving forward.

Localization is often put in contrast to globalization (Wang, 2015) and focuses on the localities, being referred to as ‘the particular’ rather than ‘the universal’ (Robertson, 2012). When it comes to marketing, localization refers to the tailoring, adaptations, and advertising towards differentiated local markets (Robertson, 2012). Taking the example of China, where the cultural mechanism is strong, products that come from foreign markets often must be ‘’localized’’ in order to be

successful (Wang, 2015). In recent years a new term, ‘’glocalization’’ - a mix between globalization and localization - has emerged, and refers to ‘’the tailoring and advertising of goods and services on a global or near-global basis to increasingly differentiated local and particular markets.’’ (Robertson, 2012, p. 194).

Moving forward to today, due to many factors such as Internet, open trade and increased travel, our environment is considered highly global. It has become a place where consumers and companies from all over the world can exchange products, services, ideas, brands, and experiences, and thus allowing the option for both local and global cultural consumption (Strizhakova & Coulter, 2019). Many scholars in the marketing field have, during the last 30 years, used globalization and localization as two parallels and studied them in relation to consumer consumption and culture (Strizhakova & Coulter, 2019). When it comes to brands, a richer brand landscape has emerged due to the rise of new brands coming from emerging markets, but nevertheless, due to the dynamics of globalization and localization processes (Steenkamp, 2019). The period when many local brands died to give room for global brands seems to have come to an end, particularly for product markets regarding beverages and food. However, some markets, such as the tech market, are still led by global brands (Steenkamp, 2019). As recognized by Özsomer (2012), keeping perceived globalness is often desirable for brands, but local adaptations are often necessary if not essential. Strizhakova, Coulter & Price (2012) even argue that globalization and localization are codependent.

Strizhakova & Coulter (2019) later mention that globalization and localization ‘’[...] are constantly clashing, collapsing, integrating, disintegrating, and further transforming one another’’ (p. 611). Since 2000, many global companies such as Unilever, Heinz and Procter & Gamble decreased their brand portfolios in order to put more emphasis and resources on the strong global brands that “[...] consumers can find under the same name in multiple countries with generally standardized and centrally coordinated marketing strategies.’’ (Özsomer, 2012, p.72). However, scholars in the field also argued that, as the world becomes more globalized, some customers also seek more localized brands. Therefore, globalization is also driving localization (Hung, Li & Belk, 2007). Steenkamp (2019) argues that the dynamics of globalization and localization have created new opportunities for branding strategies: glocalization, creolization, and hybridization. An example out of many is Starbucks, which pursues a global strategy while working strongly on appealing to local cultures. Further, Steenkamp (2019) argues that instead of a smaller brandscape due to globalization and global brands, the variety of brands is instead increasing in each individual market.

2.3 Brands & Global Brands

Brands are essential for companies’ survival and may serve as a source of competitive advantage. They have the potential power to strengthen customer loyalty, win and sustain market share, increase profits margins, and offer channel power (Aaker and Joachimsthaler, 2000). Furthermore, brands are often considered as local or global. The former, local brands, have been discussed as brands that are tailored and developed to meet the unique needs of local markets (Özsomer, 2012) and that are only available in a limited geographical market (Dimofte, Johansson & Ronkainen,

2008). Opposite to that, a global brand may be defined as a brand that uses the same brand name across markets and targets similar market segments with similar needs and wants (Douglas, Craig & Nijssen, 2001). Further, a global brand is widely available and has a universal recognition among people in the markets (Dimofte et al., 2008). However, the definition of a global brand varies in the literature.

Samiee (2019) argues that there are two main schools of defining a global brand. One school focuses on the marketing side, including the brand, the target markets, the packaging, and the availabilities in the markets. The second school focuses on consumer perception, defining a brand to be global if the consumers themselves perceive the brand as global. The latter definition is somewhat problematic since there is an actual difference between the perceived globalness of a brand from the perspective of consumers and the real globalness of a brand in terms of the reach and global availabilities (Samiee, 2019).

Özsomer and Altaras (2008) as well as Whitelock and Fastoso (2007) collected several definitions and found that these definitions defined a global brand as either about international sales, consumer perceptions or company's strategy. Steenkamp (2014) considered all these three definitions of global brand and choose to define a global brand as “[...] a brand that uses the same name and logo, has awareness, availability, and acceptance in multiple regions of the world, derives at least 5 percent of its sales from outside the home region, and is managed in an internationally coordinated manner.” (p. 7).

It has been shown that consumers assign positive attributes such as prestige, quality, and superiority to global brands (Gammoh et al., 2011; Steenkamp et al., 2002) even though these attributes are not objectively true (Özsomer & Altaras, 2008; Dimofte et al., 2008). Customers’ globalness perception of a brand has also shown to increase the preference for purchasing, even when the brand’s real globalness is low (Steenkamp et al., 2002). Due to these benefits, it has been argued that brand managers could use a global brand positioning strategy in order to strengthen brand equity (Gammoh et al., 2011).

Despite no formal or concrete definition of a global brand, these are expected to grow and increasingly dominate markets worldwide. On the other hand, Samiee (2019) concludes that cultures are not expected to converge in the future.

Looking at music festivals and their brands, Getz et al. (2010) found in a cross-cultural study between four countries that branding was considered as an important managerial strategy. In fact, as much as 69% of all festivals participating in the study stated that they had “[...] used program and marketing together to create a strong brand identity or image’’ (p. 44). Despite the declared importance of branding, only 43% of the festivals in the study declared that they had successfully developed core values associated with their brands. However, all the Swedish music festivals in the study stated that branding and brand control together with developing core values had been used as a strategy (Getz et al., 2010).

2.4 Positioning Strategies

According to Alden, Steenkamp, and Batra (1999), there are three main brand positioning strategies for companies operating globally: Global-, Local- and Foreign- Consumer Culture Positioning (GCCP, LCCP, and FCCP). When a company pursues a GCCP strategy, it uses global symbols and tightly associates them with the brand. An LCCP strategy focuses on associating the brand with the local culture, while the FCCP strategy focuses on associating the brand tightly to a chosen foreign culture (Alden et al., 1999).

Gammoh et al. (2011) investigated the GCCP of a fictive global brand and the LCCP of a fictive local positioned brand and discovered that consumer evaluations of brand prestige, brand attitude, purchase intention, and word-of-mouth were higher in the case of GCCP. In addition, the study showed that consumers who believed in global citizenship and were positive to globalness to a higher extent were more positive towards the GCCP strategy. However, a mix of global and local customer culture has also been presented in literature, named the glocal cultural identity. The consumer who belongs to this group has values and beliefs from both the global and local culture, meaning that the global and local culture coexists within the individual (Strizhakova et al., 2012). In order to position the brand, global brands can also use different cues to associate the brand with globalness or with a local culture (Alden et al., 1999). The positioning strategy framework developed by Alden et al. (1999), which was based on the semiotics theory, presents three main dimensions with associating cues: the verbal dimension, the visual dimension, and the thematic dimension. The verbal dimension relates to cues regarding the language that is communicated along with the brand. The visual dimension relates to the aesthetic cues such as spokespersons and logos that are associated with the brand, while the thematic dimension relates to story-related themes that are presented with the brand.

2.5 Market Orientation and Adaptations

From the marketing concept, an organization’s purpose is to discover and satisfy the needs and wants of its target market. If done more efficient and effective than competitors, then a company can reach a competitive advantage (Slater & Narver, 1998). To meet those needs, a company should define its market orientation, which can be defined as “[...] a strategy used to reach a sustainable competitive advantage” (Lado, Maydeu-Olivares & Rivera, 1998).

Researchers propose that the choice of strategies is largely contingent on specific product and country conditions (Wang, 1996). Satisfying market needs might lead a company to implement different adaptations in each market, and this means that some of the business activities, such as marketing activities, might be modified. By doing this, a company can be hindered to globally consolidate a set of valuable, unique, and inimitable capabilities, which then creates challenges to reach a sustainable competitive advantage in the long term. However, many companies, such as Starbucks and IKEA, implement successfully local adaptations globally while also maintaining competitive advantages (Ghauri, Wang, Elg & Rosendo-Ríos, 2016). To mention another example, Coca-Cola decided to get closer to local markets when it started suffering from declining profitability in 2000. The company’s CEO stated that they “[...] kept standardizing practices, while

local sensitivity had become absolutely essential to success.”. The company’s big successes, according to its Marketing Chief, were in markets where the company could read the consumer psyche and adjust their marketing model every day (De Mooij & Hofstede, 2002).

Although all individuals share a common humanity, the cultural differences among them force companies to consider important aspects when operating internationally (Craig, Greene & Douglas, 2005; Yalcinkaya, Calantone & Griffith, 2007). Standardized marketing mix is more likely to be successful in countries that have similar cultural backgrounds, and less likely to be transferable across countries with strong cultural differences (Griffith, Hu, & Ryans Jr., 2000; Kustin, 2004). When analyzing consumers in different countries, a company can identify different buying behaviors that can direct it to adapt its products and business systems in order to make them successful in multiple countries (Yalcinkaya, 2008). If there is a significant difference in sales or usage of a product or brand in countries that have a similar level of purchasing power, while no other variable that could explain this variance is found, then it is appropriate for a company to examine deeper the factor of cultural values between the countries involved (De Mooij, 2017).

2.6 Cultural Values

Both the consumer values and human values in general are derived from and modified through personal, social, and cultural learning. The values that are shared by members of specific groups or societies are called cultural or collective values (Clawson and Vinson, 1978; Gutman and Vinson, 1979; Vinson, Scott & Lamont, 1977). By linking cultural values and individual values, one can explain and even predict consumer behavior and choices (Oyserman, 2015; Terlutter, Diehl & Mueller, 2006).

Studies such as by Levitt (1983) argue that consumers’ wants and needs will become homogeneous in the future, considering consumer behavior being rational. However, other scholars consider this assumption to be only supported by anecdotal evidence, and that the assumption of rationality is unrealistic since it often places consumer outside of a cultural context (Antonides, 1998; McCracken, 1989; Süerdem, 1993). Therefore, consumer behavior is instead tended to become more heterogeneous because of cultural differences (De Mooij & Hofstede, 2002). Generally, when cross-cultural researchers find consistent relationships between aggregate data on various aspects of cultural values and consumer behavior, cultural values are seen as predictive and explanatory variables. Product categories, specific product attributes, benefits, and motives also tend to be related to cultural values, which results in products or brands appealing to specific values or motives that are not equally important in all countries (De Mooij, 2017).

The impacts and influences of culture on consumer behavior makes it increasingly important to understand the values of national cultures and how they can affect consumer behavior. Ignoring this phenomenon has led many companies to centralize operations and marketing, which instead of increasing efficiency, resulted in declining profitability (De Mooij & Hofstede, 2002). A common method used in cross-cultural research is to analyze secondary data of consumer behavior using country scores in dimensional models of national culture. These models include cultural values that were measured at a national level and can be used to find explanations for consumer

behavior differences and explain large differences in sales in cases where no economic or demographic explanations can be found.

De Mooij (2017) mentions three main models for international market research, which are by Geert Hofstede (2001), Shalom Schwartz (1992, 1994, 2006), and project GLOBE (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman & Gupta, 2004). The three models were also mentioned earlier by Magnusson, Wilson, Zdravkovic, Zhou & Westjohn (2008) when a comparison was made to identify differences between them. The results were that the models by Schwartz and GLOBE cluster culturally similar markets poorly when compared to Hofstede’s model, and as a conclusion, the study stated that the more contemporary cultural frameworks present only limited advancements as compared with Hofstede’s original work. It is important to note, however, that the different measures of culture might only explain particular international marketing phenomena, and that the three models of cross-cultural differences are limited. Therefore, it is still not possible to fully understand and explain consumer behavior across nations using the studies and frameworks available today (De Mooij, 2017).

2.6.1 The Hofstede Dimensions

As supported by the previous section, the multi-dimensional model by Hofstede is of interest to this study. The model has been used mostly for international marketing research and by many researchers in the past, as it proves itself as highly relevant in this subject. Furthermore, previous authors in the festival management literature suggest that future research should use Hofstede’s theory and its dimensions when trying to find explanations for the possible differences in festival management across nations (Carlsen et al, 2010; Getz et al., 2010).

Below is a short summary of each of the five dimensions of the model.

Power Distance

Power Distance relates to the extent to which a society accepts that power in institutions is distributed unequally among individuals. High power distance means that status and authority are very important, and according to Hofstede (2001), people in high power distance societies tend to be less innovative. High-power distance cultures also limit individual’s authority to make purchasing decisions while low-power distance cultures allow individuals to be more independent and develop their leadership qualities and decision-making skills (Dwyer, Mesak & Hsu, 2005; van den Bulte and Stremersch, 2004).

Individualism

Individualistic cultures value independence. Individuals in these societies are expected to look out for themselves and personal task accomplishment is put before group interest (Hofstede, 2001). In these societies, social interaction is not as strong as in collectivistic countries, which can lessen the importance of word-of-mouth effect in the adoption of new products. Additionally, communication between members might be lower in individualistic societies which can also result in less information exchange about new products (Yalcinkaya, 2008).

Masculinity

Masculinity is related to the preference for achievement, heroism, assertiveness, and material rewards for success (Hofstede, 2001). One symbolism of achievement can be demonstrated by having the latest and most novel products. Therefore, to ensure high status and recognition, individuals of masculine cultures might be more motivated to create a distinction between them and others by adopting new products (Yalcinkaya, 2008).

Uncertainty Avoidance

Uncertainty Avoidance relates to how a society deals with the unknown of the future. In high uncertainty societies, particular rules, regulations, and religions might be provided to avoid ambiguous situations (Hofstede, 2001). A high uncertainty-avoidance society might feel uncertain about adopting new products and avoid taking risks when not knowing the benefits associated with a new product (Hofstede, 2001; Yalcinkaya, 2008).

Long Term Orientation

The long-term orientation is defined as the extent to which a society exhibits a future-oriented perspective rather than a short-term perspective (Hofstede, 2001). Long-term oriented cultures value perseverance toward slow results, thrift, and adaptations of traditions to new circumstances. Therefore, individuals in these cultures are more cautious to novel ideas and might question sudden changes. In short-term oriented cultures, individuals value novelty, are expected to be more innovative and expect to see quick outcomes. This results in short-term oriented cultures to experience materialist consumption pressures which can lead individuals to adopt new products more rapidly in order to keep up with trends (Yalcinkaya, 2008).

2.6.1.1 Brazil and Sweden

Using and understanding the Hofstede’s model allows recognizing countries with high cultural differences. Considering the seven countries that Lollapalooza operates in, gaps in national scores were recognized when comparing the Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, and Chile) with the European countries (France, Germany, and Sweden). Particularly, it appeared even more relevant to analyze the differences between Brazil and Sweden, as the model shows that the two countries represent the most cultural differences from one another than any of the other countries mentioned.

According to Hofstede’s Model:

- Brazil has a high-power distance while Sweden has a low power distance; - Brazilians are collectivist while Swedes are individualist;

- Brazil is slightly masculine while Sweden is highly feminine;

- The Brazilian culture is related to high uncertainty avoidance while the Swedish culture is related to low uncertainty avoidance;

3. METHODOLOGY & METHODS

___________________________________________________________________________

In this section, the research philosophy, approach, and strategy of the study are presented together with the methodology. Further, the overall method of the research including the data collection, sampling, and data analysis are given, followed by the quality of the data collected.

___________________________________________________________________________

3.1 Methodology

The methodology section should include the general approach of the research that is being conducted. This includes stating the underlying assumptions and nature of the research problem, and the research question that will be used to encompass the research method (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.1.1 Research Philosophy and Paradigm

This study used a mixed-method approach including both quantitative and qualitative methods, therefore, there has been a conflict in what paradigm to be used. Traditionally, the interpretivist or relativist paradigm uses qualitative methods while the positivist paradigm uses quantitative methods (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Walliman, 2018). Throughout history, many experts held on to the belief that the two main paradigms with their approaches should not be combined in the same study, due to their distinctive differences in philosophy and assumptions (Walliman, 2018). According to Collis & Hussey (2014), interpretivism is mainly used in social science studies, and when researchers want to achieve an interpretative understanding of social phenomena. The interpretive philosophy assumes that social reality is built upon people's social constructs and subjective perceptions of the world, also assuming multiple realities. Furthermore, interpretivism tends to use smaller samples and allows generalizations only in similar settings (Collis & Hussey, 2014), which fits to this study. In addition, assuming subjectiveness and using qualitative methods have been essential to this study. On the other hand, gathering quantitative data was necessary to compare two samples and their experiences, preferences, and perceptions of the music festival. Thus, the study shared characteristics with both the interpretivist paradigm as well as the positivist paradigm.

However, it has been recognized that only few studies are purely interpretivist or positivist (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Instead, the two paradigms with their belonging methods can coexist in one study called mixed-methods, which allows the researcher in question to combine the philosophical bases of both paradigms which can result in even further understanding of a phenomenon (Walliman, 2018). Morgan (1979) argues that a paradigm should be used to illustrate a study’s philosophical level, social level, and technical level. To illustrate this mixed-method study, the research team thus points out that:

- On a philosophical level, this study assumed that the real world is a social reality built on social constructs;

- On a social level, the study used a deductive approach;

- On a technical level, the study used both qualitative and quantitative methods.

3.1.2 Research Approach

Since this study focuses only on the music festival ‘Lollapalooza’ in Brazil and Sweden, the study is categorized as a case study. This is because only one phenomenon was under investigation, and several methods were used to understand the case in-depth (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The case study can be described both as descriptive and explanatory as the research team focused on describing the current activities of the festival Lollapalooza as well as connecting its activities with theory, such as the fantasy cycle of customer participation (Lanier & Hampton, 2008) and the positioning strategy framework (Alden et al., 1999), to understand and explain certain perceptions and experiences from participants. Since previous theory and frameworks were constructed, developed, and used to understand this phenomenon, the research conducted may be defined as deductive (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2019).

3.1.3 Research Strategy

This study uses both quantitative and qualitative methods to gather data, using a mixed-method approach. As stated by Walliman (2018), ‘’the whole point of doing mixed methods is to widen the sources and types of data that can be collected in order to provide a richer resource for analysis” (p.173), which aligns with the purpose of this study. The methods used were an electronic survey (quantitative), interviews and one email questionnaire (qualitative). However, rather than using the quantitative and qualitative methods parallelly, a two-step approach was utilized by first analyzing the quantitative method followed by the qualitative method. This two-step approach allowed the research team to first gather a general idea of the tendencies in both samples through the surveys and later through interviews and a questionnaire, get a deeper understanding of certain phenomena that were recognized in the electronic survey.

3.2 Method

The method of a study concerns the way data - both primary and secondary - has been collected and analyzed (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.2.1 Data Collection

The process of Data collection may be defined as ‘’[...] the process of gathering information in a meaningful and reliable manner”. Examples include conducting interviews or performing environmental measurements (Porta, 2014). When data collection methods are used rightfully, the research findings’ reliability, validity and accuracy are improved, thus, resulting in credible research findings, which is the ultimate goal (Harrell & Bradley, n.d.).

The data collection of this study was based on primary data and secondary sources. The data collection included previous peer-reviewed academic articles, the study’s own survey, interviews, and an email questionnaire.

First, the literature review provided information needed to get a good understanding of what was already known about music festivals in current literature, as well as recognize the gaps. Second, the survey presented the research team a general understanding of the two samples of the study. Third, the interviews conducted aimed at providing a deeper, more qualitative understanding of attendees’ experience and evaluations of Lollapalooza. Furthermore, the interviews allowed the research team to ask probing questions that had risen from answers in the electronic survey. Finally, the email questionnaire provided the research team with a better understanding of Lollapalooza as a brand and how it operates - information that could not be found online or through the survey nor interviews.

3.2.1.1 Secondary Sources

Secondary source is collected from existing sources such as websites, books, academic databases, and industry data among others (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

3.2.1.1.1 Literature Search

The literature search of a study is defined as the ‘’[...] systematic process with a view to identifying the existing body of knowledge on a particular topic.’’ (Collis & Hussey, 2014, p.76). The literature was collected through peer-review articles from Jönköping University’s Library and Google Scholar databases. To narrow the research search process, keywords related to the research, such as music festival, international music festival, brands, global brands, localization, globalization, were used. The most recent articles were prioritized in order to find the timeliest data for this study and by the end, the most applicable articles were drawn.

All relevant articles were collected and gathered in a prepared Excel file with a table including ten columns: Article name, Author(s), Publication journal, Citation, Reference, Type of study, Theory used, Key ideas and findings, Topic, and Comments. This table helped to monitor all read articles and stay informed of their topics and theories that were later used in the literature review. 3.2.1.2 Primary Data

Primary data is defined to be the data collected from an original source, such as own conducted surveys, interviews, and experiments (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The primary data collected for this research consists of an electronic survey, interviews, and an email questionnaire.

3.2.1.2.1 Electronic Survey

Surveys are considered as a quantitative method of collecting data (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The electronic survey was created using the platform ‘Google Forms’. The questions in the survey were developed based on the literature research that had been done prior and by keeping the purpose of this study and research questions in mind. As an example, in questions 2 and 11 (see Appendix A) when asking about aspects related to the festival, all eight factors were drawn from previous

research that previous scholars had found to be important for festival attendees. The aspects were to be ranked from 1 being “Very Important” to 8 being “Less Important”. The survey included questions that differed to some extent between ranking-, closed-, and open-ended questions. To investigate the survey’s clarity, it was tested in beforehand. Two individuals, external from the research team, tested the survey and returned with feedback. The survey was then revised with some small adjustments.

After the adjustments, the survey was distributed to individuals meeting the sampling criteria of this study (see section 3.2.4 Sampling). The survey was opened for answers between 28th of March and 18th of April, and in total, 76 participants answered the survey (42 from Brazil and 34 from Sweden).

3.2.1.2.2 Interviews

The technique of using interviews for a study is considered as a qualitative method and is used when investigating what individuals think and feel about certain things (Collis & Hussey, 2014). After the data collection from the electronic survey, six interviews were made. The interview questions were semi-structured (see Appendix B) meaning that questions and themes were prepared before, but it was also possible to bring follow-up questions. According to Saunders et al. (2019), there are three types of questions that can be included in a semi-structured interview, these are probing, open and specific/closed questions. In this study, only open and probing questions were used. The use of open questions was important to understand the participants’ evaluations and perceptions. The probing questions were essential to clarify answers and the participants’ thoughts and opinions. In addition, besides the questions found in Appendix B, few individual questions were developed for each interviewee based on their answers in the previous electronic survey to collect deeper insights of their personal experiences.

The choice of language for the interviews came from the interviewees demands, being that all three Swedish interviewees were comfortable in having their interviews in English, while all three Brazilian interviewees preferred their interviews in Portuguese.

All six interviews were held online through video calls using ‘Facebook Messenger’ and ‘Skype’ platforms between 16th and 23rd of April. Details about the interviews may be found below in Table 1.

Table 1

3.2.1.2.3 Email Questionnaire

An email questionnaire was answered by a former worker of C3 Presents - the producer Lollapalooza worldwide - in order to get richer information about the organization. The initial form of this data collection was planned to be through an interview, but unfortunately due to their high workload and current circumstances (COVID-19), the interview was not possible. The research team recognizes that this results in poorer information about the organization. The individual preferred to maintain anonymity, and thus, will be referred by the fictious name of ‘Maria Silva’. For more details of the questionnaire, including the questions, see Appendix C.

3.2.2 Population and Sampling

A sample is a subset of a population whereas the population is the specific group of people, or sample units, that the researcher is interested in investigating (Byrne, 2016; Collis & Hussey, 2014). In this study, the population was formed of individuals that had either attended Lollapalooza Stockholm 2019, or any edition of Lollapalooza in São Paulo, Brazil. As the study focuses on comparing two markets and their different behaviors, two samples had to be drawn. One sample with only attendees of the festival in Brazil and one sample with attendees of the festival in Sweden. Thus, the study’s sampling criteria for the survey were: (1) Attending at least one edition of Lollapalooza in Sweden or Brazil and (2) be motivated to answer the survey so that rich and satisfactory data could be gathered. The objective was to get answers from approximately 80 people, being 40 from each country.

The sampling method used for the survey was convenience sampling and snowball sampling. For the interviews, purposive sampling was used. Convenience sampling is used in both qualitative and quantitative studies and is a non-probabilistic sampling method where people close to the researchers in question are more likely to be selected due to accessibility (Suen, Huang & Lee, 2014). One weakness of using convenience sampling is that prospect participants in the target population do not have equal chance of being selected and thus the findings from the sample are

very limited to the population (Suen et al., 2014). Snowball sampling is a non-probabilistic sample method where previous participants in the study recommend additional people from their social networks that could participate (Elliot, Fairweather, Olsen & Pampaka, 2016). This method was very effective in this study since many people went to the festivals with friends and could recommend additional participants that met the sample criteria. In attempts to increase the samples sizes in order to increase generalizability (Suen et al., 2014), the research team also searched for prospect participants on social media. For attendees of Brazilian editions, the team reached two unofficial Lollapalooza groups on Facebook, ‘Lollapalooza Brasil 2019’ and ‘LollaPalooza BR - Informações, compra e venda de ingressos’. Firstly, the approach was through a general question posted in the groups asking for volunteers to help filling the survey. When an individual replied offering help, the research team would contact them and send the survey individually through Facebook Messenger. For attendees in Sweden, the research team reached the official event page of Lollapalooza in Sweden, ‘Lollapalooza Stockholm 2019’, and searched for individuals that somehow engaged with the page, such as commenting in posts from the organization. Some of these individuals were contacted individually and asked to participate in the survey.

In regards to the interviews, the online survey had an optional question where respondents could include their contact information in order to participate in interviews, if desired. The respondents who included their contact information were first drawn for the interviews. Among these individuals, the participants that had wrote relevant information in the survey and that were expected to generate further rich information were chosen for the interviews. This sampling is referred to as purposive sampling (Suen et al., 2014).

3.2.3 Data Analysis

As recommended by Byrne (2016), a study that uses a mixed-method approach should first analyze the collected data that has been gathered by the various methods separately using analyzes that suit each method. Then, the material should be analyzed together as a whole to generate an overall interpretation aiming at answering the research questions.

The results of the electronic survey were analyzed through thematic and statistical analyses. Statistical analysis was used for questions 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12 13, 16, 17, and thematic analysis was used for the open-ended questions 3, 8, 10, 14, 15, 18, 19. In order to get an overview of the gathered data of the quantitative questions, eyeballing statistics, which is ‘’[...] looking at a set of data and making estimates of statistical values without carrying out statistical calculations.’’ (Byrne, 2016, p.39) was used. This meant that the raw data was transferred to an Excel document where graphs were created on three different pages. Page 1 being a mix of the two samples combined, Page 2 with only answers from Swedish participants, and Page 3 with only answers from Brazilian participants. Originally in the survey, the ranking questions 2 and 11 were composed of the rank 1 being “Very Important” and rank 8 being “Less Important”. Although useful for the survey answers, these rankings could not fulfill the goal for the statistical analysis through graphs. Therefore, the results of the ranks were switched to 8 being “Very Important” and 1 being “Less Important” in order to generate graphs that would demonstrate the highest values for the ‘most important’ aspects.

By splitting the data, two samples were created, and the eyeballing statistics allowed the research team to point out differences and similarities across the samples. In order to investigate if there was any statistically significant difference between the samples, independent T-tests were performed using SPSS for the results of questions 2 and 11. As both samples were composed of more than 30 sample units, normality was assumed. However, as unbiasedness can only be assumed under random sampling, the research team recognizes that there is an implication when using this test, which may affect the results.

For open-ended answers in the electronic survey, the data was transferred to an Excel file and divided between the two samples. Here, the thematic analysis was applied by scanning the data with the purpose of finding different themes, to later categorize and summarize the data (Byrne, 2016). Even though the electronic survey is considered quantitative, the research team considered the thematic analysis more appropriate in analyzing the open-ended answers - qualitative answers - of the survey.

The major qualitative data was collected through six interviews that were recorded. The first step in analyzing this data was to transcribe the interviews. The English interviews were fully transcribed by hand and with help of the online transcription platform ‘Otter.ai’. In regards to the interviews in Portuguese, only data considered relevant by the interviewer was transcribed and translated into English. Later, the data from interviews was cleaned, drawing only information that was relevant for this study, and added in another Excel document. The thematic analysis was applied, looking for themes and keywords within the samples and across the samples.

The email questionnaire used in the study was minimal and thus an analysis was not required. Instead, the answers were lightly summarized to be presented in the Empirical Findings section. After all analyses, the most relevant and important information was used. Therefore, answers that did not generate useful material for this study were subtracted and thus, not presented in the Empirical Findings section.

3.2.4 Data Quality

To deliver a good, trustworthy, and reliable study, the researchers of a study must consider and address the issues of data quality.

Reliability

Reliability concerns to what extent the research findings are reliable in terms of accuracy of measurements that are used in the study. Further, in order for the research findings to be reliable, other researchers should be able to replicate the process and get the same results - referred to as ‘’replication’’. Reliability are said to be stronger in positivist studies, where the accuracy of measurements is easier defined. On the other hand, interpretivist studies have less focus on measurements, instead, reliability concerns how well observations and interpretations may be understood and explained (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

In regards to the quantitative methods, addressing the quantitative questions from the survey, using ranking, multiple choice, and scale questions, the research team tried to state the questions as clearly as possible in order to measure each item rightfully. However, some deviations in the ranking questions were noted, which could be due to misunderstandings of ranking instructions or due to actual different preferences and opinions. That could not be determined but should be investigated if this study were to be replicated.

For the open-ended questions in the survey, the data retrieved from the interviews and the email questionnaire was categorized as qualitative data, and later analyzed by an interpretivist approach. By doing that, the research team has tried to explain the analysis process and present the findings as clear and as accurate, so that the findings would truly reflect the data.

Validity

The appropriateness of measurements, which is whether the techniques applied test the actual phenomena that the researcher investigate, is referred to the Validity of a study (Collis & Hussey, 2014). As it can be relatively hard to measure culture, adaptations, localness and globalness - or that these even can be considered as hypothetical constructs (Collis & Hussey, 2014) - the research team posed many different questions trying to capture information in regards to these constructs. Many probing questions were asked in order to investigate the reasoning behind the opinions of the participants, such as why a global music festival was preferred over a local music festival. The research team believe that the mixed-method approach, using different measurements, increased the understanding and thus the validity of this study. Saunders et. al (2019) do also state that multiple sources should increase a validity of a study.

Bias

Researchers bias may be deliberate or unconscious. Deliberate bias is when the researchers design, conduct and present the research and its finding in a biased way, often to meet a desired outcome. Unconscious bias is when the researchers are unaware of their own biases, ignoring their potential effect on the research being conducted (Byrne, 2016).

To avoid the deliberate bias, the research team firstly tried to design the research in an objective way. An extensive literature review was done, meaning that a variety of peer-reviewed articles were read and discussed. For the survey and interview questions, the research team tried to pose questions in neutral ways. In terms of presenting the data, this has also been done carefully to match the retrieved data keeping everything as transparent as possible. In regards to the unconscious bias, the research team recognized that the variety of cultural backgrounds in the team could have led to biases on the design and execution of this research, and the interpretation of the findings. However, these biases were also tried to be neutralized by discussions and attempts to bring awareness about them. In addition, the cultural biases in the research team might even have helped the understanding of the findings better since the team is composed of a Swedish member and a Brazilian member. This factor may help understanding cultural related issues or benefits that could be discussed during the study. Besides that, the research team had also an individual from Poland, which would mostly be unbiased in this matter.

Generalizability

Generalizability concerns to what extent findings from a sample can be transferred to the whole population (Collis & Hussey, 2014). As mentioned before, the generalizability of this study is rather limited since the sample was relatively small. Additionally, convenience sampling was used, which decreases generalizability.

Triangulation

Triangulation is a method that uses different types of methods to investigate the same phenomenon in order to confirm the information from different points of view (Walliman, 2018). This goes hand in hand with the mixed-method approach which was used in this study. Triangulation was used by combining the information found in the literature review with the results from the survey, the interviews, and the email questionnaire. This triangulation also attempts to increase validity.

Ethical Consideration

Ethics is highly important in research (Collis & Hussey, 2014). To ensure that all participants felt comfortable about participating in this study, the research team informed them beforehand about the purpose of the data collection, and how the data would be recorded, used, and saved throughout the research project. The research team chose to maintain anonymity for all participants in this study and therefore interviewees were coded to numbers such as ‘Interviewee 1’ , ‘Interviewee 2’ , since the real identity of the interviewees is not relevant for this study. This fact was also clearly mentioned to the participants and interviewees. In terms of data, the research team has been careful to keep all collected raw data - such as interview records and survey answers - saved on privately own devices and privately own cloud storages. All the data will be deleted at the end of the research project.

4. EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

___________________________________________________________________________

Here, the Empirical Findings from the online survey, interviews and email questionnaire are presented. Firstly, the data collected from the survey is reviewed. Later on, the data

from the interviews and questionnaire are presented.

___________________________________________________________________________

4.1 Survey

4.1.1 Age Group and Gender

General

From the 76 total respondents, the majority (63%) were aged between 20 and 25 years old, and 67% identify themselves as females.

4.1.2 Preferences about the type of festival to attend

General

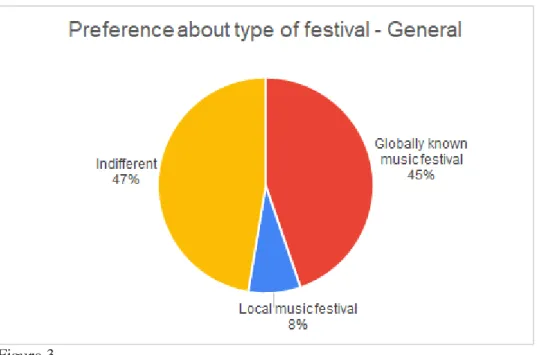

Between the 76 answers, 8% of respondents prefer local music festivals, 45% prefer attending a globally known music festival, and 47% are indifferent about this preference.

Figure 3

Brazil

Between the 42 answers, 5% of respondents prefer local music festivals, 47% prefer attending a globally known music festival, and 48% are indifferent about this preference.

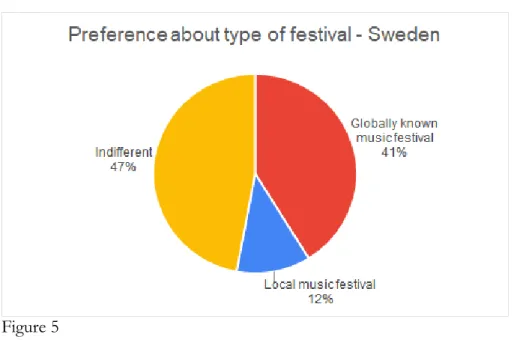

Sweden

Between the 34 answers, 12% of respondents prefer local music festivals, 41% prefer attending a globally known music festival, and 47% are indifferent about this preference.

Figure 5

Conclusion

There are not relevant differences between the preference between Swedes and Brazilians.

4.1.3 Perception about Lollapalooza

General

Between the 76 answers, 51% of respondents perceive Lollapalooza as 6 out of 6 as a global music festival.

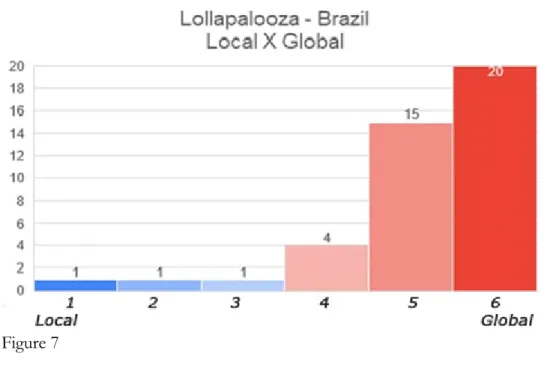

Brazil

Between the 42 answers, 48% of respondents perceive Lollapalooza as 6 out of 6 as a globally known music festival.

Figure 7

Sweden

Between the 34 answers, 56% of respondents perceive Lollapalooza as 6 out of 6 as a globally known music festival.

Conclusion

The perception of Lollapalooza being a global music festival is clear for both groups. Very few people perceive Lollapalooza as a local festival, as the grand majority perceives the festival as global.

4.1.4 Awareness about Lollapalooza editions

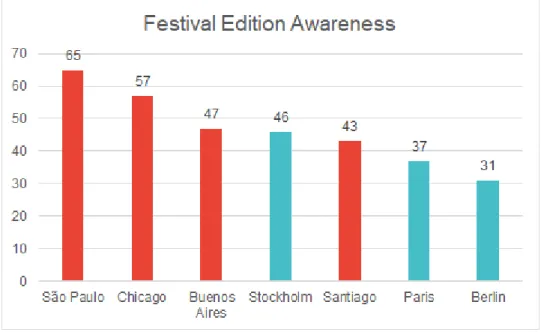

General

The festival that most respondents are aware of is the São Paulo edition, followed by the origin of the festival, Chicago. Berlin is the edition that respondents are the least aware of.

In total, the festival editions in the Americas (São Paulo, Chicago, Buenos Aires, and Santiago) are more known than the festival editions in Europe (Stockholm, Paris, and Berlin). However, this could be because the sample was majorly from the Americas region.

Figure 9

Brazil

Excluding the Brazilian edition of the festival, the Brazilian respondents are more aware of the three other editions of the festival in America, which are, Buenos Aires, Santiago, and Chicago.

Figure 10

Sweden

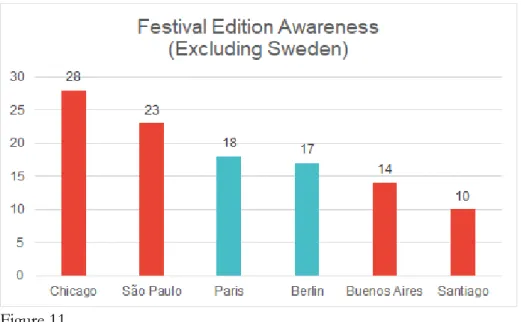

Excluding the Swedish edition of the festival, the Swedish respondents are more aware of two editions in America, the ones in Chicago and São Paulo.

Figure 11

Conclusion

- Excluding the Brazilian edition of the festival in the general awareness, the Chicago edition is the most known by all respondents.

- The other editions in Latin America - Buenos Aires and Santiago - which are the most known between Brazilian respondents, are the ones less known by the Swedish respondents.

- The European editions - Stockholm, Paris, and Berlin - have lower awareness between Brazilians and more awareness between the Swedish respondents. Still, Chicago and São Paulo are the most known editions by the Swedish respondents.

- 89% (68) of all respondents knew at least two editions of the festival.

4.1.5 Attendance behavior in Brazil

Conclusion

The respondents’ answers indicate that the behavior of attendance in the Brazilian editions could be decreasing, as most respondents have attendant earlier editions. The 2019 edition was the edition that fewer respondents have attended, with 20 respondents in total.

Figure 12

When understanding deeper which editions the attendees have been to, distinct behaviors were noticed. In total, 21 attendees have been to only one edition (either 2019, 2018, or 2017 or earlier). On the other hand, 21 other respondents have attended at least two editions.

Further, the total attendance in the Brazil editions has been declining: 300 thousand people attended both the 2017 and 2018 editions, while only 246 thousand attended the 2019 edition (G1, 2017; G1, 2018; Oliveira, 2019), representing a decline of 18% in numbers of attendance.

4.1.6 Getting to know Lollapalooza

General

Among the 76 answers, 54 respondents got to know Lollapalooza through social media, 14 through friends/family, 6 through news, and 2 through radio/TV.

Figure 14