1

How do Black Multiracial Swedes experience racial identity formation in Sweden? Biracial and Multiracial Identity Formation.

Author

Giovani Nkem Nzeafack

International Migration and Ethnic Relations Bachelor Thesis

15 Credits Spring 2020

2 Abstract

This thesis examines how biracial and multiracial individuals experience racial identity formation in Sweden. An investigation was conducted into their childhood and upbringing to explore how these experiences shape the way that their identity is formed. To arrive at the results of this dissertation, six individuals who self-identify themselves as Black biracial Swedes where recruited to participate in the data collection process. This mean that this research has used primary tools such as semi-structured interviews to collect data from the participants. This study has used two contemporary positive theories of biracial and multiracial identity formation which are Poston’s Biracial identity model and Roots resolution for resolving otherness. Within these two theoretical frameworks, the research question and aim will be answered through analysis of the respondents. Themes that were used to analyse the interviewees responses where alienation from racial identity, picking a side, language as identity and, familiar support and negative experiences. The results finding shows that most interviewees experience a challenge in the process of identifying themselves with a specific racial group leading to a development of a gap in the process of

self-identification.

3

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 2

Chapter 1: Introduction ... 4

1.1 Problem Statement ... 5

1.2 Research Aim and Research Question ... 7

1.3 Key Terms and Concepts ... 8

Chapter 2: Literature Review ... 9

2.1 Biracial Identity Development: The Global Context ... 9

2.2 Biracial Identity Development: The Swedish Context ... 13

Chapter 3: Methodology ... 16

3.1 Constructivist Approaches ... 16

3.2 Qualitative Approaches ... 17

3.3 Recruitment and Analysis ... 18

3.4 Sample Demographics and Representativeness ... 19

3.5 Validity and Reliability ... 20

3.6 Limitations ... 22

3.7 Researcher Positionality ... 22

Chapter 4: Theoretical Framework ... 24

4.1 Poston’s Biracial Identity Development Model ... 24

4.2 Root’s Resolution for Resolving Otherness ... 27

4.3 Application ... 29

Chapter 5: Analysis ... 30

5.1 Alienation from Racial Identity ... 30

5.2 Picking A Side ... 31

5.3 Language as Identity ... 34

5.4 Familial Support and Negative Experiences ... 35

Chapter 6: Discussion and Conclusion ... 37

4

Chapter 1: Introduction

Self-identity can have a strong impact on the way that people see themselves, their behaviours and actions, and the habits that they keep (Gkargkavouzi, Halkos and Matsiori, 2019). Many people have a cultural identity that is “inherited” from their parents, which in part is due to the culture, memories, and narratives that are spun through the fabric of our upbringing (Wang, Song and Kim Koh, 2017). For many ethnic minorities, this is reinforced by external pressures, such as racisms and discrimination based on appearances or these cultural traditions (Forster et al., 2017). For biracial people, self-identity has the potential to become more complex, in that there may be two (or more) cultural traditions present in the home and discrimination from both sides; that is, being somehow identifiable as not a

member of any of the cultural or racial categories within a society (Franco, Katz and O’Brien, 2016). There can also be a number of internal elements of self-identity that develop through an understanding of the self and personal preferences (Franco, Katz and O’Brien, 2016).

One of the challenges that can arise is when these internal and external factors clash. Some studies suggest that racial identity invalidation is one of the most stressful racial experiences that a biracial person can face (Rockquemore and Brunsma, 2004; Townsend, Markus and Bergsieker, 2009). This can come in the form of accusations of racial

inauthenticity, the imposition of racial categories from external sources that do not align with the internal self-identity of the individual, and forced choice dilemmas (Townsend, Markus and Bergsieker, 2009). While there has been much research on the topic of biracial identity and this type of stressor, less is known about how an individual will form their identity and how these can be “resolved” from an internal perspective. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore themes of biracial identity development in Sweden with a view to understanding the conflicts and resolutions that can arise within this context.

5 1.1 Problem Statement

Sweden is now one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world, well on par with countries like Canada and the United Kingdom (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019). Although the national statistics database does not publish information on biracial individuals specifically, around a third of the population are born abroad or are born in Sweden and have one or two foreign-born parents as of December 31, 2019 (Statistiska Centralbyrån, 2020). Unlike many of the other ethnically diverse countries, however, there is the assumption that Sweden is an ethnically homogenous country (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019). This stems from the fact that the ethnic diversity in the country seen today is a result of immigration in the 1980s and 1990s, rather than from a colonial legacy that dates back much further (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019).

The fact that immigrants from Africa are a more recent phenomenon in Sweden means that much of the research on biracial identity outside of Sweden can be problematic to apply to this context. As immigration is more recent, there has been less time for interracial couples to form and have children, thus meaning that biracial identity is less embedded in Swedish culture than in some other places (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019). Self-identification is the answer to “who am I?”, but it is also formed by attachments to others around us, which means that this needs to be taken into consideration when understanding how biracial

individuals develop their identity (Myers, 2009).

A study conducted by Sarah Gaither, in the article titled ‘Mixed’’ results: multiracial research and identity exploration’’, found that multiracial individuals experience rejection from multiple racial groups (Gaither, 2015). When you are a Black multiracial (having one White parent and one Black parent), you are not White enough to identify with a

predominantly white group at school/community and vice-versa (Gaither, 2015). Results from another study conducted by Latson (2019) in the US show that the complexity that

6

comes with how multiracial individuals identify themselves, particularly in terms of the aforementioned identity mismatch between self-identity and external categorization. A survey from the studies shows that a quarter of multiracial people experienced confusion and

frustration about who they are; meanwhile, one in five feel pressure to claim a single race (Latson, 2019). Moreover, the research by Gaither is not only limited to the negative challenges that multiracial individuals encounter. The article pointed out that having a multiracial identity is advantageous as some biracial or multiracial people can “race switch” and therefore fit in with more segments of societies than those who are monoracial (Gaither, 2015).

As previous research in mostly Anglophone countries have shown that multiracial individuals face rejection from multiple racial groups both in society and family, this thesis will seek to examine the factors that influence the racial identity development of Black multiracial Swedes in Sweden, reflecting on their experiences from when they were children up to when they became adults. By doing this, the research will analyse how their

experiences influence their racial identity development. Also, because there is little academic research on critical mixed-race studies in the Nordic countries compared to Western

Anglophone countries such as the U.K. and U.S (Sanset, 2018), this thesis will seek to address this research gap within the field of critical mixed-race studies and international migration and ethnic relations in the context of Sweden.

Therefore, by answering the research question and achieving this thesis's aim, new determinant factors influencing racial identity formation of Black multiracial Swedes will be presented through a qualitative analysis of their childhood and adulthood experiences in Sweden. Sandset’s (2018) book, Color That Matters, acknowledges that research on mixed racial or mixed ethnic individuals is under-studied in the Nordic context. According to him, there are only three studies about diverse racial and ethnic individuals in Norway and a few

7

scholarly articles in Sweden and Denmark (Sandset, 2018). Due to the scarcity of research on mixed-race individuals in Scandinavia and Sweden in particular, further research is essential. This thesis will contribute to or understanding of mixed-race experience in Sweden.

1.2 Research Aim and Questions

The main aim of this thesis is to examine how Black multiracial Swedes experience racial identity formation in Sweden.

Research questions:

• How do the childhood experiences influence the ways they form racial identity? • How do the adulthood experiences influence the ways they form racial identity?

To achieve this aim and to answer the research question, this thesis will use a thematic analysis approach to analyse these experiences of racial identity formation through the lens of Poston’s biracial identity development, which takes an equivalent approach and Root’s Theory of Resolving Otherness which takes a variant approach. Within these two theoretical frameworks, the research question and aim will be answered through analysis of the

8 1.3 Key Terms and Concepts

Sue (1981) defines racial identity formation as one's pride in their racial and cultural identity. It is essential as it helps individuals shape their attitudes and others who belong to the same racial groups (Poston 1990, p. 152). Identity development is defined as a life span process that relies on internal and external forces such as family structure, physical

appearance, and cultural knowledge (Roberta, 2010). Also, multiracial individuals are those whose parents have different racial backgrounds or have two or more distinct racial groups (Ashley, 2011). This study refers to Black multiracial Swedes as people with a multiracial or biracial identity, for example, when you have a European mother and a father from Africa.

9

Chapter 2: Literature Review 2.1 Biracial Identity Development: The Global Context

Several researchers and scholars have globally researched in the field of race identity construction of biracial/multiracial individuals. The research on multiracial identity is common in western Anglophone-cultures, where they see identity as something uniquely possessed by individuals (Lawyer, 2014, p.2). In these western Anglophone cultures, the identities for minorities are seen as being in trouble. It carries with it negative affiliations such as criminality, theft, and all kinds of failures (Lawyer, 2014). To answer the research question and to achieve the aim, this thesis will review previous research conducted in the western Anglophone countries and then relate it to the Scandinavian context to shed more light on the research area in Sweden.

Rockquemore and Delgado (2009, p. 25-16) affirms in their research that multiracial individuals with a specification to those who have black and white parents in the US have been central to theorists when developing models of race identity. Their motivation is due to the racial divides between Blacks and Whites in the US (Rockquemore and Delgado, 2009). The article used four approaches of race construction to describe research on mixed-race individuals in the United States. These approaches are the variant, ecological, problem, and the equivalent approach. The problem approach is an early theory of race identity

construction for multiracial individuals; meanwhile, the variant, ecological, and equivalent approaches are modern theories of race identity construction. They do predict negative outcomes in having a mixed identity in the US (ibid). The results from the problem approach from the article state that individuals who identify as multiracial face stigmatization,

isolation, and rejection from both the majority and minority racial groups in the US These experiences faced by multiracial individuals when navigating American society have

10

enormous negative impacts on them, such as inferiority complex and moodiness (Rockquemore and Delgado, 2009).

The findings of La Barrier’s (2017) research on multiracial identity development in the US in the article titled ‘Multiracial identity development: illuminating influential factors’’ show that multiracial individuals in the United States of America construct race identity through family and community influences (p. 2-4). According to La Barrier, the two essential family factors that influence racial self-identification of multiracial individuals are caregiver's (parents) use of racial labels with youth, and the observed racial predominance within the family (La Barrier, 2007). The role of one's family is significant and has a fundamental impact on the individual and their identity (La Barrier, 2007, p. 2). The article findings also showed that the community has a high impact on the racial identification of multiracial individuals. Community aspects related to the development of racial identity for individuals with multiracial heritage include the diversification of the community and contingent

socialization (La Barrier, p.3). The article results show that multiracial individuals in the US who have support from their families, neighbourhoods, social networks, and those with diverse educational backgrounds tend to develop healthy self-confidence and racial identity (La Barrier, 2007, p. 6).

Renn’s (2008) research on biracial and multiracial identity development amongst multiracial US college students shows that physical appearance, cultural knowledge, and peer culture influence their identity development (p.17). By physical appearance, the article looks at attributes such as skin tone, hair texture, and colour, the shape of the eye and nose (Renn, 2008). By using Root’s (1990) resolutions for resolving Otherness that one's option is to accept the identity that the society assigns to them, multiracial student's choice of

identification faces constraints by how others are interpreting their appearances (Renn, 2008, p. 18). To Renn, multiracial individuals always need to negotiate the campus racial landscape

11

with appearances that are not easily recognizable by the others (Renn, 2008). In terms of cultural knowledge that multiracial college students learn from families, parents, and community before attending college, those who are well armed with the knowledge of their diverse cultural backgrounds feel more confident in their self-identification (Renn, 2008). This is represented in the appreciation stage of Poston’s model of identity development for multiracial individuals (1990, p.154). Peer culture, resistance from monoracial students of colour, and racism amongst white students are aspects of a peer culture that influence the ways multiracial and Biracial US college students experience their race identity formation (Renn, 2008, P. 19).

In the context of identity development of biracial individuals, Pang (2018, p. 192) study conducted in Scotland explored the identity formation of biracial individuals, and the role family plays in the process. The study's findings show that the actual identification process of biracial individuals are often contingent upon and shaped by structural constraints and relationships across life discourse (Pang, 2018). According to Pang, biracial identities are forged out of social relations and shaped by interactions with intimate ones (Pang, 2018). The study found that individuals with good knowledge about their biracial background were able to negotiate an otherwise stigmatizing non-white identity. Meanwhile, mixed-race individuals who viewed their biracial identity as a peripheral attribute were more likely to be brought up under a unique identification where their non-Scottish heritage was ignored (Pang, 2018, p. 192). The principal arguments central to Pang's study were that biracial identities are

constructed by the meanings arising from social interactions with significant others, allowing them to develop self-knowledge associated with collective identity categories (Pang, 2018, p. 197). Also, essential arguments raised in Pang's study were that early experiences at home influence how biracial identities are being shaped (Pang, 2018).

12

For Root (1998), who conducted a study on the experiences and processes affecting racial identity development for multiracial individuals in the US used an ecological model to examine 20 sibling pairs. The study found out that the experience of trauma-related severely influences the racial identity development of multiracial individuals to racism, discrimination, and community socialization to race-related issues and beliefs. The findings also show the emergence of four factors that influence the racial identity process of multiracial individuals: hazing, family dysfunction, the impact of integration, and other salient identities (Root, 1998). The findings on another study by Tizard and Phoenix (1995) about adolescents with one White and one African or African-Caribbean show that the racial and cultural identities of biracial individuals are being shaped or influenced by choice of school they attended, their social class as well as the degree of politicization of the youth's

attitudes towards race (in Jackson, 2009, p. 295).

Another study conducted by Csmadia et al. (2011) on the racial identification and developmental outcomes among Black-White multiracial youths in the US show that the geographical region is shaping multiracial individual’s racial identity development, type of neighbourhood, phenotype, and family structure (p. 37-40). The experiences with which one’s family has with race help multiracial youths in the US negotiate their racial identification. Based on the family's racial position within American society, parents of multiracial individuals transmit to them access to education and economic and cultural opportunities compared to families that lack such opportunities (Csamadia et al., 2011). Parents who are versed with living in racialized societies tend to teach their children about race, which therefore helps them maximize their success within the community, which leads to their racial identity development (Csamadia et al., 2011). In the US, people are assigned to racial categories that establish a hierarchy and shape social relations amongst groups

13

youths in the US live in influence their racial identification (Csamadia et al., 2011). Also, individuals assigned to their racial groups in the US are based on socially selected phenotypic characteristics such as skin colour, body, lip, and eye shape and hair texture (Omi & Winans, 1994, in Csmadia et al. 2011 p.39).

Moreover, a study in the US conducted by Mawhinney and Petchauer (2013) examines biracial identity development in adolescent years using fusion autoethnography. The study used an ecological approach to demonstrate how family, peers, and school curricula validate and reject racial self-presentation of biracial individuals (Mawhinney and Petchauer, 2013). This study intended to help researchers understand how complex and fluid biracial and multiracial identity formation relates to everyday school spaces and processes (Mawhinney and Petchauer, 2013, p. 1312). By using the continuum of biracial identity model (COBI), the study found out that biracial identity development is non-linear which means that there are multiple variables of influence and multiracial individuals can locate themselves at different point along a continuum of identity development (Mawhinney and Petchauer, 2013, p. 1326).

2.2 Biracial Identity Development: The Swedish Context

As noted above, there is less research available on the Swedish context of biracial identity development. This is, in part, because Sweden has experienced a large growth in immigrants of colour over the past few decades. One of the most thorough explorations of the mixed-race experience in Sweden is by Hübinette and Arbouz (2019) who conducted semi-structured interviews with 18 Swedes who identified themselves as either “mixed” or “half”. In this study, all of the interviewees felt that they had been treated differently because they had an “atypical Swedish” appearance (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019). The study also noted that Swedes of mixed descent typically grow up in homogenous and White neighbourhoods and attend schools that are also homogenous and White (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019). These

14

researchers suggested that the Swedish experience is different from those of other Western countries in part because of political decisions made there. Mixed Americans or Brits are recognized as their own statistical and social category (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019). It can be argued that hegemonic Swedish antiracist so-called “colour-blindness” means that it is nearly impossible to verbalise issues of race (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019). This is reflected in the fact that, since 2003, there are no race categories provided by the Swedish statistical office and instead people are categorized by the country of origin of their parents. Those who have one or two Swedish-born parents are counted and categorized as having a “Swedish background”, for example (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019).

Another study that focused on interracial relationships and on transnational adoption is instrumental in understanding how these experiences shape family policies, family

building, and everyday life in Sweden (Osanami Törngren, Jonsson Malm and Hübinette, 2018). This study, too, focuses on the fact that Sweden has historically been an ethnically and racially homogenous country until the end of the 20th century (Osanami Törngren, Jonsson Malm and Hübinette, 2018). Again, there is a focus on the “colour-blindness” of Swedes and their perception of themselves as being liberal and anti-racist and the impact that this has for those who wish to identify themselves with their racial background more proudly (Osanami Törngren, Jonsson Malm and Hübinette, 2018). There were three analytical themes present in this research; first, the fear of talking about race in Sweden because of this perceived colour-blindness; second, racialization based on the parenthood of the individuals; and third, the problem of belonging (Osanami Törngren, Jonsson Malm and Hübinette, 2018).

Although these studies are interesting and useful in setting the background for this current research, there is nowhere near the depth of exploration in Sweden that there are in other ethnically diverse countries. The purpose of this thesis is to add to this expanding area of research by focusing on the experiences that these individuals have as biracial Swedes and

15

how these experiences fit into the development of their identity, whether this be as biracial or some other identification.

16

Chapter 3: Methodology

The purpose of this chapter is to outline the data collection methods and methodology used for this current study. Prior to addressing the methodology and recruitment, it is

important to understand how biracial and multiracial identity impacts on these participants. The interview started by asking the participants “How do you identify yourself in terms of race?”, which was designed to ensure that all of the participants were appropriate for the current research. In this case, all of the interviewees identified themselves as multiracial or biracial. This is important as not all biracial individuals, particularly those who are of mixed Black and White heritage, identify themselves as such; some identify themselves as Black only (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010).

3.1 Constructivist Approaches

This research is based on the constructivist approach. The ontological question on the nature of reality is answered by constructivists as being a product of mutual understanding; this is not to say that there is no external experience, but that the way that people understand the world is by giving this external world a meaning built on mutual understandings. As people construct social connections, people also construct meanings for these external

experiences (Moses and Knutsen, 2012). Constructivists believe that the world is experienced through the human mind which means that there are socially constructed patterns that have social and contextual influences (Moses and Knutsen, 2012). The epistemological question of how we know things in research is typically viewed by sharing or building this knowledge between researcher and participant (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010). In this case, the ontological approach is social constructivism which posits that knowledge stems from social interactions between people. Racial categorization in society is such a construct, in that the delimitations between different races cannot be thoroughly ascertained and as such the

17

position of an individual in this categorization is not fixed and relative to others in the social network (Lynch, 2017).

3.2 Qualitative Approaches

A constructivist approach typically leads to a qualitative methodology, in that the qualitative approach allows for participants to respond with their own understanding and interpretation of social constructs (Lynch, 2017). This thesis, therefore, uses a qualitative research method. Primary data was gathered through semi-structured interviews, which involved six participants who self-identified as both Black and multiracial. All participants were Swedish and had lived their whole life in Sweden, allowing for an analysis of racial identity formation within the Swedish construct. Semi-structured interviews rely on a good relationship between interviewer and interviewee and a thorough knowledge of the research aim (Silverman, 2006). Interviews are useful tools for a social constructivist because they allow for rich insights into perceptions of social constructs and into the experiences, attitudes, and feelings these individuals have (May 2011, p.131).

The purpose of choosing a qualitative approach in this context is that there are many different ways in which a self-identity can be formed, and it is important to understand the specific context in which these individuals have developed (or are developing) their identity. In this case, the choice of a semi-structured interview comes from the flexibility of this approach in ensuring that the data collected can stay on topic and focused while still allowing the participants to express ideas or themes that may not have been apparent in past literature (Silverman, 2006). The benefit of this is that it can be used for foundational quantitative research in the future that has a broader application as the themes have already identified, thus seeing how common these are in the general population can be conducted at a later stage.

18 3.3 Recruitment and Analysis

To answer the research question, six Black multiracial Swedes were recruited to participate in this study. The interviewees were recruited by placing a Facebook post on the social media account of the researcher. In this case, of course, the participants were self-selecting and limited in that they were all personally known to the researcher or known to someone within the social network of the researcher. The Facebook post specified that individuals who identified as either biracial or multiracial and had Black heritage were asked to contact the researcher via telephone, Facebook messaging, or email, all of which were provided in the initial post. Four of the participants were not personally known to the researcher before the interviews were conducted, while two were direct contacts. The interviewees themselves selected their racial identity, which is important to note as the topic of external identity was covered in the interviews. The first interviewee to respond was Chandra, and she asked if she could “snowball” other participants with similar racial identities to participate in the program. Chandra recruited Laura, and Laura recruited her elder sister Juliet. Boris made direct contact with the interviewer through the Facebook post. The second two participants, Amy and Zach, contacted the interviewer through the Facebook post at a later stage and added to the sample a few months after the initial four interviews to add more data to the sample.

The interviews with Chandra, Boris, and Laura were conducted via WhatsApp audio call. Juliet participated using Facebook messenger audio call. Amy and Zach were

interviewed separately via Zoom. This was a departure from the intended research approach due to the limitations of Covid-19, and the research was originally intended to be conducted face-to-face. The conversations were recorded with the explicit consent of the interviewee. Prior to the meeting, the researcher sent informed consent forms to the participants about the nature of the dissertation, the way that the data would be handled and used, and how the data

19

would be represented in the thesis (see appendix I). These were signed and returned via email. An interview invitation letter was also sent to participants to give more insight into the research and allow the participants to self-reflect prior to the interview (see appendix II). The data collection was guided by an interview guide with 25 closed- and open-ended questions (see appendix IV) that was based on prior research into biracial identity. All interviewees were above the age of 18.

The interview questions themselves were framed to allow the interviewees to provide their own answers about their experiences and beliefs in their racial identity, experiences of racism and stigma, and demography. After recording and transcribing the interviews, the key themes of the interviews were identified by the researcher by noting common phrases and experiences between the participants. This approach allowed for an understanding of the textual meaning within the data set. The data was also coded using coding software to

understand the themes of the interviews more formally. The coding software used to code the data that has been transcribed was Quirkos.

3.4 Sample Demographics and Representativeness

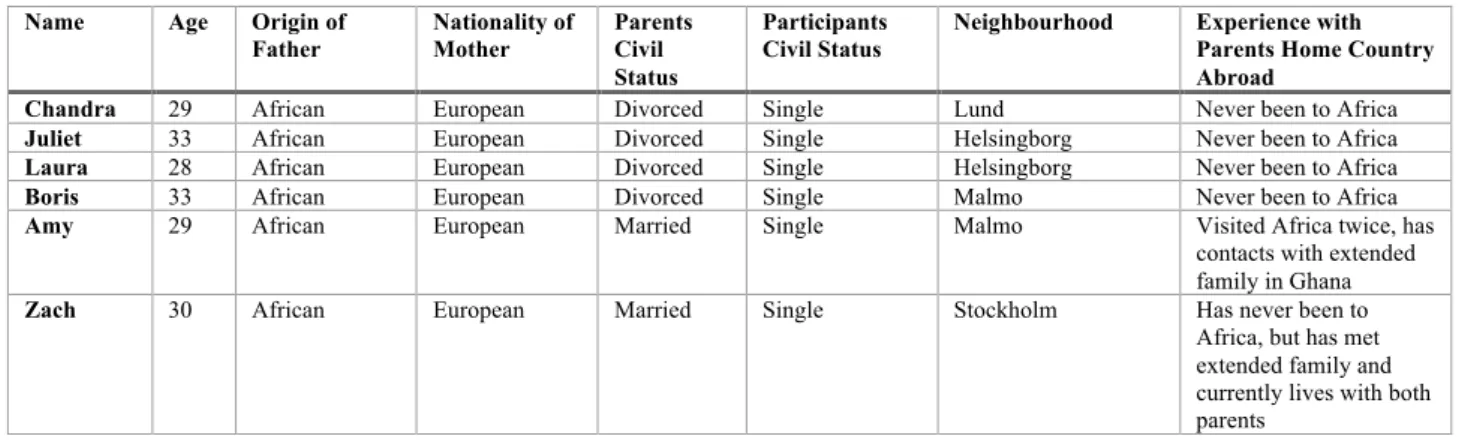

This study aimed to interview six participants between the ages of 18 and 35 about their experiences. As shown below, the participants were between 28 and 33, which represents a narrower segment of the biracial Swedish population than originally intended. The study included only those who identified their biological parents as being Black and White; no other racial identities were included. Originally, six participants were recruited for the study, three males and three females. Unfortunately, two male participants withdrew from the study without giving a reason; calls and contact attempts were not returned. Two more participants were added at a later stage, one male and one female, which means that there is a female-skew in the experienced represented here. Figure one, shown below, gives an

20

Name Age Origin of Father Nationality of Mother Parents Civil Status Participants Civil Status

Neighbourhood Experience with Parents Home Country Abroad

Chandra 29 African European Divorced Single Lund Never been to Africa

Juliet 33 African European Divorced Single Helsingborg Never been to Africa

Laura 28 African European Divorced Single Helsingborg Never been to Africa

Boris 33 African European Divorced Single Malmo Never been to Africa

Amy 29 African European Married Single Malmo Visited Africa twice, has contacts with extended family in Ghana

Zach 30 African European Married Single Stockholm Has never been to

Africa, but has met extended family and currently lives with both parents

Figure 1. Description of participants (names have been changed to protect privacy) There are some clear obstructions to the representativeness of this sample. Firstly, only three African countries are represented in the nationality of the father. Those who have a parent from other countries may not have the same experience of identity formation. Another issue is that four participants have divorced parents and little contact with their Black father, which again may shape the way that they form their identity, particularly in childhood. Only one of the participants has visited the home country of her father, which again may have an important role in shaping her personal experience of self-identity and identity formation. Another key thing to note is that all of the participants had a Black father and a White mother. This means that there are no other biracial identities included (such as Black and Asian) or experiences that involved growing up with a Black mother and a White father. The original purpose of this research was to explore biracial identity more generally, but these participants helped to narrow down the topic to Black multiracial Swedes as this was the given identity of all six participants.

3.5 Validity and Reliability

The reliability of research refers to whether or not future researchers could carry out the same project and produce the same results, interpretations, and claims (Silvermann, 2006, p. 281). In qualitative research, two criteria satisfy research reliability (Silvermann, 2006). This is done by making the research process transparent by sufficiently describing the research and data analysis methods and paying attention to theoretical transparencies

21

(Silvermann, 2006). Therefore, this research is reliable and transparent as the researcher has explained the methods used to collect data, how the data were transcribed, coded, and

analysed in correlation with the theoretical framework used in the project. Hamersley defines validity as the ‘extent to which an account accurately represents the social phenomenon to which it refers’’ (Silvermann, 2006, p. 288). In this case, there the validity is present in that it mirrors some of the findings from past research and the social phenomenon described by the participants is similar throughout, despite the different backgrounds of the participants.

3.6 Ethics review

This thesis includes sensitive personal data such as race and ethnicity. There is a need for the rights and values of the participants to be protected. The review application was sent to the Ethics Council following standard procedures of students at the faculty of culture and society. A letter of invitation was sent to the participants. This explained the research topic with tips on how to prepare for the interview. An informed consent form was also sent to each participant who then signed and returned to the researcher via email. Those who were unable to send via email did a verbatim confirmation of their voluntary participation in the research. All interviews lasted between thirty-five to forty-five minutes. Also, the permission to record was approved by all applicants. Applicants were also told to withdraw participation at any point in time in case they become uncomfortable and not to disclose any data that is against their will when responding to the interview questions.

Moreover, these participants were promised anonymity, and this was done by changing their names in the research and avoiding the use of their specific country of origin in this research. This was to protect their identity from being traced. The participants were also informed about the utility of the research. They were promised that this research is solely for the purpose of a Bachelor thesis and not for any other commercial or personal reasons. As

22

earlier mentioned above, this research was approved by the Ethics Council after a careful review of the detail research description.

3.7 Delimitations

The major delimitation of this research is the sample. The participants were mainly those of mixed Black and White racial identity, which means that the findings of this research cannot be used to extrapolate views from those who are of mixed Black and other ethnicities. In addition to this, the majority of the participants grew up in a single-parent household with little contact with their Black father and his home country, which again may have an

important role in shaping the experiences of these participants. Another issue to consider is that these individuals are all in their late 20s and early 30s, and the experiences of younger and older biracial Swedes may not share the characteristics identified by these participants. This should be considered when understanding and interpreting the results of this research.

The COVID-19 pandemic also put delimitations on who could be recruited for this research and how they could be interviewed. As semi-structured interviews typically rely on the rapport and trust between interviewer and interviewee, this may have impacted the

results. Finally, this research is not gender balance as it has recorded four female interviewees and one male.

3.7 Researcher Positionality

The researcher has different roles to play when exhibiting a qualitative research method. Data collected from the respondents is analysed through human perspectives instead of using related tools such as questionnaires. May reiterates that conducting qualitative research means that researchers can either work from the perspective of an outsider or that of an insider (May, 2011). The benefit of being an insider in research is that you have primary knowledge of the field of study, which will guide you in collecting the right data. However,

23

as far as this study is concerned, the researcher considers himself as an insider. The

researcher is directly involved as he is a parent of Black multiracial Swedes living in Sweden. The research used closed and open-ended questions to collect data that did not project his views. The researcher only worked with the data that was collected from respondents to produce the results. My experiences as a parent guided me in asking the right questions to the interviewee and gaining trust.

24

Chapter 4: Theoretical Framework

The purpose of this chapter is to present the theoretical framework used to explore the experiences of biracial and/or multiracial individuals. In this case, there are two racial

identity development theories that have been used to look at how racial identity is formed.

4.1 Poston’s Biracial Identity Development Model

Poston developed the Biracial Identity Development Model because he believed that previous models of minority identity development did not reflect the experiences of

multiracial individuals. This led him to propose a new and positive model in 1990, which moved away from negative themes of identity development that focused on the struggles that ethnic minorities (Soliz et al., 2017). Earlier theories, such as that suggested by Stonequist (1937, in Finney, Tadros, Pfeiffer and Owens, 2020) suggested that biracial people would always occupy a marginal position and that there could be no healthy resolution of the racial identity of these individuals. The biracial identity development model was also one of the first attempts at conceptually explaining multi-ethnic racial identity development and highlighted that these individuals were more likely to experience some turbulence in

development as they attempted to integrate mixed backgrounds into their identity (Soliz et al., 2017). This model also incorporates the work of Cross (1987) in references to the concept of reference group orientation (RGO) attitudes (Poston, 1990, p.153). Cross (1987) made a distinction between personal identity (PI), which includes the constructs of self-esteem and self-worth and is independent of race categorization, and RGO which includes the constructs such as racial identity, racial esteem, and racial ideology.

Poston (1990) identified five stages of identity development, each of which is tied with specific challenges and outcomes for the individual as these stages are resolved. During the first stage, Poston suggests that biracial individuals tend to have some awareness of race and ethnicity but have their own sense of identity that is not tied to these issues (Poston,

25

1990). At this stage, young children have little awareness of race as their RGO attitudes are under-developed (Phinney and Rotherham, 1987). Their identity at this stage is therefore firmly rooted in PI factors such as their self-esteem, which they obtain from their families (Phinney and Rotherham, 1987). The presence of both parents at this stage can help to build on this and gradually expose them to the norms, beliefs, and traditions of both parental heritages, which commonly occurs during the childhood of biracial individuals. In some cases, such as when one parent is absent from the home, this can occur later. It is difficult for children to understand or have a biracial identity during this time as it can be challenging to incorporate multiple cultures into their understanding (Poston, 1990).

The second stage is the group categorization stage, in which individuals feel the influence from outsiders and therefore feel pressure to choose a racial identity. Typically, this is an identity that represents one racial group rather than both (Poston, 1990). This stage is when the biracial individual can experience an identity crisis, which Poston defines as the stage of “alienation” (Poston, 1990, p.153). Biracial individuals can experience

marginalization at this stage and may only understand this at a later stage (Poston, 1990). Individuals are more likely to rely on personal factors such as physical appearance, cultural knowledge, and environmental factors such as group support (Renn, 2008). Multiracial and biracial individuals will typically experience pressure to choose which parental heritage they identify with as the cost of belonging in a society (Renn, 2008). Biracial individuals also develop a need to participate in family, peer, and social groups during this stage and the parental ethnic background is influencing their belonging in these groups (Hall, 1980). The eventual “choice” that is made will likely be based on the neighbourhood of the individual (a status factor), the parental style and relative influence of each parent, acceptance and

participation into the culture of various groups (group support factors) and appearance, knowledge of languages, cultural awareness, and age (Hall, 1980). The choice of group

26

categorization during this stage is essential in defining later identity development (Poston, 1990).

The third stage is the enmeshment or denial stage. Individuals may experience confusion and guilt as they have selected one heritage over the other, and therefore do not identify with any or all aspects of their heritage (Renn, 2008). This can lead to feelings of anger, self-hatred, shame, and lack of acceptance from one or more groups (Poston, 1990, p.154). Biracial individuals may also experience further marginalization during this stage as they begin to question their sense of belonging. In addition to this, depending on the external environment, biracial individuals can become ashamed of having one parent that is of a different racial background than the majority race in their area (Poston, 1990). The issues of guilt and confusion need to be resolved before the more positive elements of identity

development seen in the latter stages can be achieved (Renn, 2008).

The next stage is, therefore, the appreciation stage. This is where an individual learns about and begins to appreciate both parents’ cultures and heritage (Poston, 1990). During this stage, the individual will have a better awareness of both of these cultures but still tend to identify with one group over another (Poston, 1990, p.154). Individuals at this stage are typically influenced by personal factors, group support factors, and status factors as outlined above. This stage is accompanied by an increased knowledge about their racial heritage and a tendency towards recognizing and appreciating all of the racial identities and cultural factors that make them unique (Roberta, 2010). At the end of this stage, biracial people will develop an established and integrated identity (Poston, 1990, p.154).

One of the criticisms of this theory is that it removed the emphasis of societal racism in the lives of people of colour, something which is found in the older models of monoracial identity development by Cross. Later scholars have since reintroduced societal racism as a

27

factor in biracial identity development (Finney, Tadros, Pfeiffer and Owens, 2020),

something which will also be considered in the following analysis. Another element that is missing from this theory is that there can be multiple healthy identity outcomes for

multiracial people (Finney, Tadros, Pfeiffer and Owens, 2020). Again, multiple identities depending on the external environment of the individual will be considered where relevant.

4.2 Root’s Resolution for Resolving Otherness

Root (1990) developed her theory on biracial identity formation at around the same time and, like Poston (1990), the theory focuses on the positive approach rather than older models that suggest that there can be no successful identity formation for this cohort. Root (1990) also used some of the existing models of minority identity development, such as Atkinson, Morten and Sue (1979) but altered them to fit specifically with the biracial

experience. In this case, Root (1990) noted that many biracial individuals with White heritage reach adolescence they do not have the same opportunity to reject majority (White) culture and immerse themselves in a minority community. This is because these individuals may be rejected from these minority communities or because they would feel shame and guilt for rejecting the White part of their heritage (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010). Root also noted that those that are partly White enter a period of turmoil and a potential “dual

existence” (1990, p.1200) where they do not feel as though they belong into a social group. They may also experience being asked to be the minority representative, which has a specific impact on biracial teens as it erases one part of their identity.

Root (1990) suggested that there were four positive resolutions that can come from the tensions of biracial identity. Each of these can be positive depending on how the individual feels about the outcome. The first is that the individual accepts the identity that society has assigned them, which may or may not align with their biracial heritage. In this case, having family and a strong alliance with a racial group – typically the minority group –

28

and feeling accepted by this group act as support mechanisms for the individual which allows them to feel positive about membership. The second is that the individual feels identification with both racial groups. This depends on societal support and the person’s ability to maintain this identity (Root, 1990). In this case, the individual must be able to resist categorization into one of the racial identities that form this overall racial identity from outsiders (Root, 1990). This can be more possible in countries that have more biracial individuals as there may be less need for others to sort people into a specific monoracial group (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010).

The third is identification with a single racial group. This is similar to the first

outcome in that the individual has only one racial identity. The difference is that this is a self-selected racial identity rather than an acceptance of an external racial grouping. This can also occur as the fourth resolution, which is identification as a new racial group. In this case, the individual may move between racial groups socially but has an identity that is aligned with other biracial people (Root, 1990). This can be others from the same mixed heritage or with others from any specific heritage background who are also biracial (Root, 1990).

The benefit of this theory is that it accounts that people may want to identify as a single racial identity, but this might not necessarily be the one that society assigns for them. They may choose to identify as only one of their parents’ heritage groups or an entirely new

racial identity altogether (Root, 1990). This theory also allows for people to self-identity in

more than one way at the same time or to change their self-identity depending on external or internal factors (Root, 1990). This is a way of understanding biracial identity development in a non-linear way, which is a nice counterpoint to the Poston (1990) approach that suggests that people will follow each of the stages in a particular order.

29 4.3 Application

These two theories have been selected to guide this research and to interpret the data because they are both positive models; they both allow for an understanding of biracial identity development that does not suggest that these individuals cannot find a self-identity of their own or that they will always struggle with this identity (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010). In addition to this, Poston (1990) provides insight into how a racial identity could develop over time for a biracial individual, which will be applied here in terms of understanding the childhood or developmental experiences of the participants. Root (1990), on the other hand, takes a more flexible approach that is used for understanding how the individual feels about their identity now, which will be used to examine the participants’ responses in the present tense.

30

Chapter 5: Analysis

The purpose of this chapter is to present the findings from the coded interviews with reference to the aforementioned theoretical frameworks. Each of the common themes in the interviews will be discussed individually by using individual quotes from the interviews when these are particularly illuminative, or representative of the experience or theme expressed.

5.1 Alienation from Racial Identity

One of the common threads between each of the interviews was that the participants felt that there was some “alienation” from their own identity as a biracial person. As noted by Root (1990), there can be positive outcomes to the biracial identity formation process, but in some cases alienation from racial identity or being assigned a racial identity that does not match the internal perception of identity can lead to negative emotions (Soliz et al., 2017). Laura gives some interesting insights into the identity fluidity that she experiences depending on the context, which can lead to alienation. She notes that she identifies as Swedish when she is outside of the country when explaining where she is from to others. She also notes that she does not say she is Nigerian because she has never been to Nigeria (although Chandra defines herself as Ethiopian and also has not been to Ethiopia, this does not seem to be definitive as a theme). Laura does note that she explains that she has Nigerian heritage but that she hates when people ask her about her racial identity because she feels that they “put her in a box”. She feels that stating that she is Swedish (her nationality) should be enough and she rarely identifies herself as Nigerian or Finnish, where her mother is also from.

Another experience that appeared as a theme is that people tend to qualify these individuals as something other than biracial and neither Black or White. Boris notes that other people have asked whether he is Brazilian because he does not look “as Black” as people from Africa, whereas Laura notes that people often wonder if she is Latina. Amy

31

noted that people often believe that she is biracial but that she comes from the United States, where it is perceived that mixed biracial couples are more common. Zach has been asked if he is from India. This suggests that there is a need to categorize people by their skin tone and features that may not align with the nationality of either parent or the internal identity of the individual, which could lead to internal confusion. As noted by Poston (1990), identity formation can be influenced by external factors and there is a tendency to align oneself with one parental identity over the other due to perceptions from the outside. In this case, however, it is interesting to consider what happens when the assigned racial category from the outside is not representative of either cultural or racial heritage. Interestingly, those who had been miscategorized in this way did not express any negative feelings towards these experiences, instead choosing to focus more on their feelings about their own identity than those of others.

As noted by Hübinette and Arbouz (2019), misrecognition occurs when the individual has their identity contested or questioned as a way of either including or excluding them when categorizing them as a Swede. One of the notable elements of these interviews is that people never “mistook” them for being a Swede, but always placed them in the category of other regardless of what that category was. This can lead to feelings of alienation from individual racial identity but also the marginalization that biracial individuals experience in Swedish society that comes from this misrecognition. Indeed, the findings from these interviews align with those found in the literature, where White Swedes typically try to categorize biracial individuals as being from a certain country rather than acknowledging them as biracial (Hübinette and Arbouz, 2019).

5.2 Picking A Side

The literature review, and the two theories of biracial identity development, highlights that many biracial people may feel as though they have to choose an identity or “pick a side”. For Poston (1990), it was the resolution of this to find an identity that incorporated elements

32

of both racial heritages that is the positive outcome; for Root (1990), a singular identity could still be a positive identity formation as long as the individual feels some empowerment in that identification. In the interviews, the situation appears to be more complex. Amy noted that many White people that she encounters do not perceive her as being White, although this is not necessarily used as a tool for exclusion. She also notes that many Black people she meets, particularly those from outside of her childhood and immediate family, do not consider her to be Black.

Root (1990) noted that many biracial people tend to identify more with the minority racial background if they are to choose a side. This can be seen in the interview with Chandra, who suggests that when she was younger, she wanted to be white. When she reached the Gymnasium level of schooling, however, she met more Black people and

surrounded herself with people of a Black racial identity (she does not specify whether any of these friends were mixed biracial). For Chandra, she felt that she was openly embraced by the Black friends in Lund and that she allowed herself to discover more about her heritage

through these friends. She noted “when I am with Black people I am so comfortable and just myself” …and that “no White is coming close to me because I gonna follow my roots”. She identifies herself as Ethiopian despite having a Swedish/Hungarian mother and her father was absent in her life. The interesting thing about this case is that Chandra was put into foster care and does not have a good relationship with her mother either, which may be why she tends to express her feelings towards White people with more hostility than the other participants (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010). Chandra also notes that she wishes that she was not mixed at one point during the interview, stating that she feels that she is Ethiopian and has no affinity for Sweden as a country at all.

Boris also notes a special affinity for the Black side of his racial identity than his white. Boris is aware that he can identify himself as Black, White, or mixed when he states “I

33

will say that I am racially mixed, but I feel more Black than I feel White, I think”. Boris feels that there is less acceptance from the majority racial group and therefore prefers to align with the minority racial group because it makes him feel like he matters. He is in the appreciation stage of the Poston (1990) biracial identity model in that he has an appreciation for both sides of his heritage and has chosen to identify with one racial group over another. Compared with Chandra, above, Boris has chosen to align himself with the Black side of his identity from a more external perspective because he is aware that he is treated differently to his monoracial White friends, but he has a good relationship with his mother which may be why he has less need to completely remove the White heritage from his self-identity (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010).

Overall, the view that the individual must pick one racial identity was common to all six participants, and all six identified as Black or Black biracial rather than focusing on the White side of their heritage. This aligns with previous research that suggests that the majority of Black biracial people identify as having a Black RID or a biracial Black/White RID, rather than a White RID (Gillem, Cohn and Thorne, 2001). There are those who qualify themselves as Black but do not deny their White heritage and those that wish they were exclusively Black, such as Chandra above (Gillem, Cohn and Thorne, 2001). This may be because these studies take place in countries with a specific history of racial categorization that emphasizes the “other” in mixed heritage individuals. The so-called “one drop rule” is a cultural approach to racial categorization that emphasises that whiteness is the “default” with additional racial identities being the “pollutant” (Reece, 2019). This is more common in Western countries. It is also known that the skin tone of the individual shapes the multiracial identity formation process, with those who have lighter skin tones experiencing more racial fluidity than those with darker skin tones (Reece, 2019). In this case, then, the experiences of these respondents is in line with the experiences of those from other Western countries where Black RID is

34

emphasized over White RID as there is often exclusion from White spaces based on skin tone (Reece, 2019).

5.3 Language as Identity

Another common theme between these interviews was the association between language and identity. Although language is an important part of culture, it is not extensively discussed in the literature on biracial identity, particularly in the United States where Black biracial people are assumed to come from an African American and White American

background (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010). As noted above, since immigration of non-Swedish people is a more recent phenomenon, people have brought their language with them, which may explain the differences between the Swedish and American experience (Lusk, Taylor, Nanney and Austin, 2010). In addition to this, writing on the Black biracial experience in other Western European countries such as the United Kingdom and France means considering the colonial experience of even more recent (African) immigrants (Aspinall, 2003). Many biracial people living in the United Kingdom, for example, have a parent that speaks at least one African language and English or French, meaning that language use in the family context is not necessarily exclusive of the national context as it would be in Sweden (Aspinall, 2003).

For those in this study, the relationship between the Swedish language, paternal national/local language and self-identity was more complex. Laura noted that Swedish people tended to open conversations with her in English, rather than Swedish, assuming that she was a more recent immigrant herself. Having grown up in Sweden with a Swedish mother,

however, she speaks Swedish and the fact that people assume she does not can invalidate the Swedish part of her identity somewhat. Zach noted a similar feeling, stating that “when people assume I do not speak Swedish, it tends to highlight the fact that I look different to

35

white Swedes over anything else”. There is an assumption that people who are biracial do not speak Swedish because they cannot have grown up in the country.

Another interesting finding relating to language is the experience of people with their Black African community. Chandra noted that “when you go to … Black people they are like yeah but you do not know your language so you’re not Black”, reinforcing the idea of

alienation from both sides of her heritage. As with many of the other participants, Chandra did not have a close relationship with her father and has not visited his home country, so it is not surprising that she would not speak his native language. Amy also noted that when she meets people from her university that come from Ghana, they are surprised to find out that she has Ghanaian heritage because she cannot speak any of the government-sponsored languages of the country. This can increase feelings of distance between the individual and the side of the family that speaks a certain language, as was shown in research on Black-Korean Americans learning to speak Black-Korean (Kim, 2016).

5.4 Familial Support and Negative Experiences

Another theme in the interviews was the development of self-identity with respect to those around them. As noted above, Chandra experienced the foster system and therefore had less familial support than the other participants. She is also the only respondent who felt less comfortable in identifying herself as Swedish, suggesting that she is Ethiopian alone. With reference to Root (1990), this seems to suggest that Chandra is identifying herself with the categorization that society has given to her; she also notes some feelings of otherness when comparing herself to White Swedes and some uncomfortable experiences that she has had when being around this demographic. Her Black friends, on the other hand, offer her support and a feeling of being welcome, which may be why she identifies herself with this Ethiopian label rather than as Swedish. The fact that her negative experiences growing up may have shaped her current identity and how it was formed is an interesting finding to consider.

36

Other participants noted that they had some familial support, and this was important in shaping the way that their identity formed. When asked about their relationships with their parents, Boris noted that he had both parents around until slightly later in his childhood compared with Juliet, Chandra, and Laura. This helped him to become aware of his biracial roots through living with both parents until he was 11 years old. Chandra grew up in a foster home, which meant that she had less contact with her parents; Laura and Juliet had some experience in foster homes. Amy and Zach, on the other hand, also noted that both parents had an influence over their identity formation as they grew up with both parents and therefore had both as an influence. Boris noted that “I would say my father played the biggest role in how I build my self-identity. My father came to Copenhagen 50 years ago, the racism at that time was different, you know, he has scars on his face because Danish people were throwing stones at him”. He noted that “he is feeling it a lot, being honest, and so he was harder with me he told me different things like you’re Black, so you need to work twice as hard as the White kids in school”. Amy and Zach reported similar experiences noted by their Black fathers, and these three also seem to have the most “resolved” understanding of their racial identity in that they all cited themselves as being biracial before Black, with Boris suggesting that he felt biracial but more Black than White.

37

Chapter 6: Discussion

As per the aim and research questions, this chapter will focus on the discussion that will incorporate the results obtained from the analysis of the information collected from the interviews of the various participants who took part in this study, and the theories which are applicable in various scenarios to explain the different information provided. According to the analysis results, most interviewees experience a challenge in the process of identifying themselves with a specific racial group leading to a development of a gap in the process of self-identification. This situation is associated to the way the different interviewees responded differently when explaining their identity.

In examining multi-ethnic and multiracial identities, one should understand that identity is a process that individuals go through. Different factors take part in self-identification, making one identify themselves with a specific ethnic group. According to Osanami (2019), individuals identify themselves through modes such as kinship or friendship, while others may identify themselves through attributes such as ethnicity, race, language, gender, or nationality. Experiences and the pressures that individuals go through from other people also play a significant role in self-identification. Such situations show how self-identification is a process that individuals go through from their childhood as they grow and identify with a given ethnic group related to Poston’s five stages where he sees development as a process of self-identity, choice of group categorization, denial, appreciation and integration as the last stage in identity development (Poston, 1990). Such factors are evident from the biracial and multiracial interviewees influenced by the different aspects of their identity in the diverse Swedish society.

The development of a multiracial and multiethnic generation in Sweden significantly impacts children sired from partnerships formed across nationality, ethnicity, race, and religion. This situation, which is new in Sweden compared to other countries such as the United States and other countries in Europe, has caused much confusion to the new generation in the way

38

they should identify themselves in the Swedish society. This situation is similar to the United States or European situation, where individuals are classified as either white or non-white. Root (1990), however presents a multiracial/biracial identity model; though its application may, at times, be impossible, as a process involving five stages. These stages are presented as acceptance of the identity assigned by the society, identification with both racial groups, identification with a single ethnic group, identification as a new racial group and finally presenting a symbolic identity. The identification of individuals with a non-white phenotype in Sweden is not considered Swedish. An in-depth analysis of the interviews indicates that multiracial or biracial individuals in Sweden are beyond whiteness. Most individuals emphasize the cultural belonging of the individual and their nationality (Osanami, 2019).

The existence of the varied self-identification gap among the different interviewees can be associated with the biracial identity development model, which shows how identity development is a slow process related to individuals' experiences when they grow (Moses and Knutsen, 2012). Even though some individuals self-identify themselves as Swedish or mixed, most of the other participants use the traditional dichotomy of coming from an immigrant background that is more than detailed than the self-identification of non-whites in the United States where the blacks are considered to have their roots from Africa. This gap is associated with various factors such as language, alienation of identity, and picking sides that come into play where individuals self-identify themselves as non-Swedish.

Even though skin color is considered a significant factor in identifying individuals as either Swedish or non-Swedish, the self-identification process is still a great matter to most non-Swedish individuals. They have to go deeper to identify themselves with a racial group where they feel welcomed or fitting (Hübinette, 2017). This situation is associated with the alienation process, where the mixed-race individuals have to choose to identify themselves with one ethnic group and not the other (Aspinall, 2003). This situation has made individuals'

39

self-identification fluid in nature and not a fixed or objective state of identity. In this case, the identification process is beyond the traditional way of identification based on ancestry's whiteness due to the increased intermarriages between individuals from different ethnic backgrounds experienced in the Swedish society (Osanami, Malm, & Hübinette, 2018).

According to Osanami, Malm, and Hübinette (2018), the color-blind ideology in Sweden is associated with difficulties in distinguishing the process of racism even though the concepts of culture and ethnicity are widely accepted in the country and mostly used to analyze and understand the process of racial expression (Renn, 2008). In this case, the parents and transracial children are viewed differently based on their origins, physical appearances, historical and social contexts. In this case, the examination of discrimination does not include the adoptees' view and their perspective on how they view themselves. Also, the various reports maintained do not show how the individuals contribute to keeping their beliefs, family norms, ancestry, and national belonging (Osanami, Malm, & Hübinette, 2018). Due to this reason, the interviews provide an in-depth analysis of the way individuals who have biracial or multiracial backgrounds view themselves and how such perceptions influence the way they are treated or classified in terms of race or ethnicity.

Therefore, it is evident that how biracial and multiracial individuals self-identify themselves play a significant role in how they are classified in the racial identification process in Sweden. The process is considered to be very technical due to the various factors which come into play when individuals self-identify themselves with a specific group of individuals in Sweden, making the process to be very different as compared to other places such as Europe and America, where cultural diversity and racism is experienced.

40 Conclusion

In conclusion, the main aim of this thesis is to examine how Black multiracial Swedes experience racial identity formation in Sweden. The childhood and adulthood experiences of six individuals who self-identify as Black multiracial Swedes were analysed from data collected through semi-structured interviews. Data analysis shows that most interviewees experience a challenge in the process of identifying themselves with a specific racial group leading to a development of a gap in the process of self-identification. To arrive at thesis results, common themes were picked from the coded interviews which were then analysed with reflection of the research participants responses in corelation with Poston and Roots biracial identity models. Some of the themes that have been used for the data analysis includes alienation from racial identity, picking a side, language as identity and, familiar support and negative experiences.

In the literature review, this thesis has presented the experiences of having a biracial background globally and then further narrows it to fit the Swedish contexts. From the

materials available in Sweden, it is clear that the study of mixed racial individuals is under research compared to anglophone countries such as UK and USA. Therefore, this research is relevant to the contribution of mixed-race studies in Sweden. The major delimitation that this thesis encounter was the sample as it only reflects the biracial experiences of individuals who originates from African and European communities. For further research, it will be essential to increase the sample population from six to at least eighteen participants to derive a broader perspective in the context of Scandinavia.