ACCESS TO PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATION AND CHOICE OF METHOD IN A SUICIDE ATTEMPT by

Talia Lyn Brown

B.A., University of Colorado Boulder, 2009

M.S., University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, 2012

A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Epidemiology Program 2017

This thesis for the Doctor of Philosophy degree by Talia Lyn Brown

has been approved for the Epidemiology Program

By

Carolyn DiGuiseppi, Chair Heather Anderson, Advisor

Gary Grunwald Peter M. Gutierrez

Robert Valuck

Brown, Talia Lyn (Ph.D., Epidemiology)

Access to Psychotropic Medication and Choice of Method in a Suicide Attempt Thesis directed by Assistant Professor Heather Anderson

ABSTRACT

Suicide and attempted suicide are a major public health concern in the United States, together responsible for approximately 44,000 deaths, 200,000 hospitalizations, and nearly 500,000

emergency department visits annually. The choice of method during suicide attempts is the most important factor impacting survival. It is also an important avenue for intervention to prevent suicide attempts. Suicide attempts with psychotropic medication are common. Simply having access to a psychotropic medication via prescription (or prescribed access) could be an important factor increasing the risk of using psychotropic medication in a suicide attempt. The aims of this

dissertation were two-fold: to understand, in a United States population of individuals who attempted suicide, 1) the relationship between having a recently filled psychotropic prescription (i.e., anxiolytics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and stimulants) and using a psychotropic drug in a suicide attempt and 2) the prescription-related and demographic factors that could influence that relationship. These aims are important to inform suicide prevention efforts. The PharMetrics Legacy Claims Data, a large patient-centric medical and pharmacy claims dataset, was used to explore the defined aims. Diagnosis codes were used to identify a population of first time suicide attempters and define cases (i.e., individuals using psychotropic medication in an attempt) and controls (i.e., individuals using all other methods). Exposure was defined using filled prescription information in the 90 days prior to the attempt. Multivariable logistic regression and interaction tests were used to explore pre-identified relationships. I determined prescribed access to

psychotropic medication to be an important factor influencing the use of a psychotropic drug in a suicide attempt. The relationship between prescribed access and method choice appeared to vary

by psychotropic drug type, where individuals with access to antipsychotic/mood stabilizer or stimulant medication were most likely to use that medication in a suicide attempt, though more research is needed to confirm identified differences. I also found that the demographic factors age, gender, and region of residence modified the relationship between prescribed access and method choice. Findings from this study could inform development of population and individual-level means safety interventions (i.e., interventions that target securing medication) to prevent suicides.

The form and content of this abstract are approved. I recommend its publication. Approved: Heather Anderson

This dissertation is dedicated to my parents Robin and Shirley Brown, who taught me that hard work and a little stubbornness can get you far.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This dissertation culminates four and half years of the most challenging and rewarding times of my life. I could not have done this without the support of so many people. I would like to especially thank my advisor Dr. Heather Anderson for her contributions to my dissertation and immense growth as a researcher. I could not have finished this momentous project without her guidance, patience, and steadfast commitment.

I would also like to express my sincerest thanks to the rest of my committee members, Drs. Carolyn DiGuiseppi, Peter Gutierrez, Gary Grunwald, and Robert Valuck, who always had their doors open to me for help, and whose boundless wisdom contributed greatly to my project and personal growth.

In addition, I would like to extend a special thanks to Dr. Carol Runyan whose training and support in the early days of my doctorate work laid most of the groundwork for this dissertation. I am so grateful for her continued mentorship and support.

I would be remiss not to take the time to also thank the many students, faculty, and colleagues over the years who made me the researcher and public health professional I am today. I am forever thankful for my fellow doctoral students who always were there to talk through problems and celebrate mini accomplishments; the many professors who inspired me through their passion and knowledge; and my colleagues at Boulder County Public Health who work so hard every day to improve our community.

Finally, I must express my very profound gratitude to my family and my partner, Brandon, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this dissertation. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ...1

BACKGROUND ... 1

SPECIFIC AIMS AND HYPOTHESES... 2

SIGNIFICANCE ... 4

II. LITERATURE REVIEW ...5

BURDEN OF SUICIDAL ACTS ... 5

METHOD CHOICE ... 7

FACTORS INFLUENCING METHOD CHOICE ... 8

MEANS SAFETY... 16

CONCLUSION... 17

III. MATERIALS AND METHODS ... 19

STUDY POPULATION ... 19

IMPORTANT MEASURES ... 24

ANALYSIS ... 34

IV. ACCESS TO PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATION VIA PRESCRIPTION IS ASSOCIATED WITH CHOICE OF SUICIDE METHOD: A RETROSPECTIVE STUDY OF 27,876 SUICIDE ATTEMPTS ... 44

ABSTRACT ... 44

INTRODUCTION ... 45

METHODS ... 46

RESULTS ... 52

V. AGE, GENDER, AND REGION OF RESIDENCE MODIFY THE INFLUENCE OF ACCESS TO

PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATION VIA PRESCRIPTION ON CHOICE OF SUICIDE METHOD ... 62

ABSTRACT ... 62 INTRODUCTION ... 63 METHODS ... 64 RESULTS ... 68 DISCUSSION ... 75 VI. DISCUSSION ... 80 PRESCRIBED ACCESS ... 80 COGNITIVE ACCESS ... 84 MEANS SAFETY... 85 LIMITATIONS ... 88 STRENGTHS ... 92 NEXT STEPS ... 93 CONCLUSION... 95 REFERENCES ... 96

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

Background

Suicide and attempted suicide are a major public health concern in the United States, together responsible for approximately 44,000 deaths, 200,000 hospitalizations, and 500,000 Emergency Department visits annually.1,2 Despite large national efforts to curb suicide,3,4 rates continue to

increase.5 The method used during a suicide attempt (or method choice ) is the most important

factor impacting survival during that act.6–11 Method choice is also an important avenue for intervention to prevent suicidal acts since evidence indicates a person is unlikely to use a different method if the preferred method is not accessible.12 Research investigating factors influencing

method choice in suicide attempts exists12,13; however, more is needed, specifically focusing on

factors influencing less lethal method choice. Identifying factors influencing method choice informs suicide prevention efforts. Most relevant are efforts to restrict access to methods commonly used in suicide attempts, referred to as means safety .

Intentional poisoning occurs in 16% of suicide deaths and 68% of non-fatal suicide attempts presenting in the emergency department (ED), with prescription medication making up 80% of all intentional poisoning events.1,14 The majority of medications used are analgesic or psychotropic

(drugs that target chemicals in the brain).15,16 Prescriptions for medication, especially psychotropic

drugs, have increased significantly in recent decades.16 There is some evidence that physical access

to psychotropic medication influences the use of that medication in a suicide attempt.17–26 A few studies also identified a link between having a filled prescription for psychotropic medications (or

prescribed access ) and use of psychotropic medication in a suicide attempt.20,23,25,26 However, many

questions remain. First, if the association between prescribed access and method choice identified in community-level studies also exists in individuals is unknown. No studies have explored this

question using data from US populations. Second, the influence of prescribed access on choosing psychotropic medication versus other medication remains unclear. Third, differences in the

influence of prescribed access on method choice among different types of psychotropic medications (i.e., anxiolytic, antidepressant, antipsychotic, mood stabilizer, or stimulant) have not been

examined. Fourth, differences in the relationship of prescribed access and method choice by demographic groups have not been studied. Finally, the literature does not establish how factors related to the psychotropic prescription (i.e., da s suppl , le gth of a ess, o egula it of refills) could influence the choice of psychotropic medication in a suicide attempt versus a different method. Understanding how prescribed access influences method choice would help identify potential means safety interventions and higher-risk groups to target for suicide prevention.

For this dissertation, I used a large and nationally representative insurance claims dataset to understand how, in a population of individuals attempting suicide for the first time, prescribed access to psychotropic drugs influenced the likelihood of using a psychotropic drug during that attempt. I evaluated differences between psychotropic drug types and explored the influence of prescription-related factors on method choice in a population of individuals with prescribed access. Finally, I examined possible modification by demographic factors. My specific aims and hypotheses are described in detail below and presented visually in Figure 1.1.

Specific Aims and Hypotheses

Specific Aim 1: Examine the relationship between prescribed access to psychotropic drugs and method choice during a suicide attempt.

Hypothesis 1 - Individuals using a psychotropic drug in a suicide attempt (case) will be more

likely to have prescribed access to psychotropic medication compared to those using non-psychotropic drugs (control 1) and those using all other methods (control 2).

Specific Aim 2: Explore the relationship between prescribed access to specific psychotropic drug groups and method choice during a suicide attempt.

Hypothesis 2- Individuals using a specific psychotropic drug group in a suicide attempt will be

more likely to have prescribed access to that specific type of psychotropic medication compared to those using non-psychotropic drugs (control 1) and those choosing all other methods (control 2).

Figure 1.1 Conceptual Model.

Specific Aim 3: Determine if prescription-related or demographic characteristics influence the relationship between prescribed access to psychotropic drugs and method choice during a suicide attempt.

Sub-aim 3.a: Examine, in a subpopulation of those with prescribed access, whether prescription-related factors (i.e., le gth of a ess, regularity of refills, or average days’ supply) i flue e the likelihood of using a psychotropic drug in a suicide attempt.

Hypothesis 3.a- Individuals who have longer access to prescribed medication or a larger average

da s suppl o who more regularly refill their medication are more likely to use psychotropic medication in a suicide attempt compared to those using non-psychotropic drugs (control 1) and

Prescribed Access to Psychotropic Medication

Suicide Attempt with Psychotropic Medication Aims 1 and 2

Demographic Modifiers Age, gender, region

Aim 3b

Prescription-Related Factors Length of access, average days’

supply, regularity of refills

Aim 3a In a sub-population of individuals with prescribed access

Sub-aim 3.b: Examine if demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, and region of residence) modify the relationship between prescribed access to psychotropic drugs and method choice during a suicide attempt.

Hypothesis 3.b-The relationship between prescribed access to a psychotropic drug and using a

psychotropic drug in a suicide attempt is significantly modified by gender, age, and region of residence.

Significance

The purpose of this study was to understand the influence of prescribed access to

psychotropic medication on method choice, in a population restricted to individuals who made a suicide attempt, in a large paid pharmacy and medical claims dataset. Additionally, this study explored other factors that could impact or modify the likelihood of an individual using psychotropic drugs during a suicide attempt. These relationships have not been explored in the United States or in a large managed care population, so insights gained from this study could greatly increase our knowledge about factors influencing choice of less lethal methods in the United States and

contribute to the more prolific international literature on this topic. Additionally, findings from this study could identify individuals at high risk of using medication prescribed to them for a suicide attempt, helping clinicians make more informed decisions about means safety for clients in need of psychotropic medication. This study could also identify possible means safety interventions for high risk groups. Better knowledge about factors influencing method choice in a suicide attempt could prevent attempts, and would inform future means safety prevention and intervention strategies at both individual and population levels.

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW Burden of Suicidal Acts

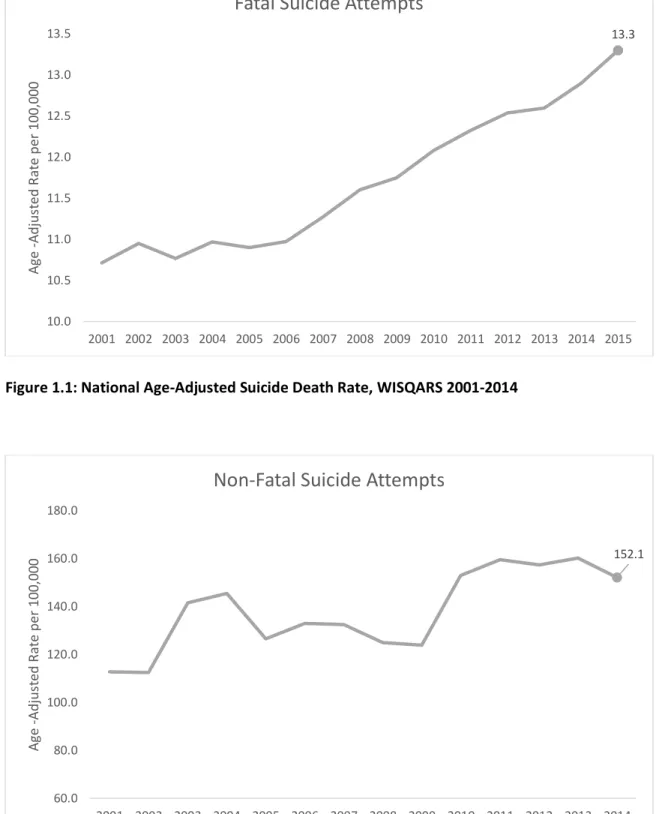

Suicidal acts, comprised both of suicide deaths and suicide attempts, are a major public health problem in the United States, with rates that have been increasing despite large national prevention efforts (Figures 2.1 &2.2).1,3,4 Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death with over 44,000 people

dying in the United States in 2015.1 Also, suicide attempts resulted in over 200,000 hospital

admissions, and nearly 470,000 emergency department visits in 2014 – poisoning being the most common method used.1,27,28 All told, non-fatal suicidal acts cost the United States over 4 trillion

dollars in medical expenses a year with a single hospitalization costing around $11,000 and a single ED visit $4,000.1 Most suicide research is focused on understanding risk factors to predict fatal

suicide attempts; however, because of their financial burden on society, toll on suicidal individuals and their families, and high risk of suicide reattempts, more research focused on preventing non-fatal suicide attempts is needed. Lack of research into non-non-fatal suicides is especially prominent in the United States.27,29,30

The method used in a suicide attempt is the most important factor determining whether or not the individual survives that attempt.10,31,32 Additionally, there is evidence that means safety – or

est i ti g a ess to a i di idual s p efe ed ethod – could potentially prevent or at least postpone an individual from attempting suicide.12,33,34 Most of the research on method choice and

means safety, especially in the United States, has focused on factors influencing choosing a lethal method,13 but less is known about factors influencing the choice of less lethal methods. More

research is needed to understand factors that influence method choice, to understand how means safety of less lethal methods could prevent suicide attempts.

Figure 1.1: National Age-Adjusted Suicide Death Rate, WISQARS 2001-2014

Figure 2.2: National Age Adjusted Rate of Non-Fatal Suicide Attempts from a sample of Emergency Departments, WISQARS 2001-2014 13.3 10.0 10.5 11.0 11.5 12.0 12.5 13.0 13.5 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 A g e -A dj us ted R a te pe r 1 0 0 ,0 0 0

Fatal Suicide Attempts

152.1 60.0 80.0 100.0 120.0 140.0 160.0 180.0 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 A g e -A dj us ted R a te pe r 1 0 0 ,0 0 0

Method Choice

The lethality of a suicide attempt is predominantly determined by the method used to carry out the attempt.13 Considering broad categories of methods, firearms are the most lethal method

used in the United States with over 85% of individuals dying from the attempt, followed by hanging/strangulation (67%), fall/jump (31%), poisoning (2%), and finally cutting/piercing (1%).5

Nearly 80% of individuals dying from suicide use highly lethal methods (i.e., firearms,

hanging/strangulation, and fall/jump), which is why research has historically focused on these method choices. However, since over 80% of combined fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts involve less lethal methods, they represent a far greater public health burden.

Over 75% of suicidal acts involve some form of poisoning, with around 15% leading to death, 80% leading to hospitalizations, and 50% resulting in ED visits.1,31 Poisoning is defined as the

ingestion or inhalation of a substance with toxic properties. In the International Classification of Disease Version 10 (ICD-10) and 9 CM (ICD-9 CM) coding, intentional poisoning is a broad category that includes use of prescription and over-the-counter medication, illicit drugs, other solid or liquid substances like bleach, and gaseous substances like carbon monoxide in a suicidal act. In the United States and other developed countries, prescription and over-the-counter medication are most commonly implicated in poisoning-related suicide deaths and attempts, with 60-80% of intentional poisonings involving a drug.1,15,35,36 Analgesics (i.e., acetaminophen, salicylates, and opioids), and

psychotropics (i.e., anxiolytics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and stimulants) are the medications most commonly used in suicide attempts and deaths.15

Psychotropic Medication

Be ause a aila le o li e ue tools e.g., CDC s We -based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS)) that provide fatal and non-fatal suicide data only provide information on the count and rate of fatal and non-fatal poisoning suicides, it is difficult to quantify the

proportion of drug suicide attempts involving psychotropic drugs. However, there is evidence they are regularly used in suicide attmepts.37–39 One study in reproductive-aged women found that 40% of hospitalizations for intentional drug poisoning involved a psychotropic drug.40 Another study of

poison center data found that of the top ten poisons reportedly used in suicidal acts, half were psychotropic, though this figure is nearly 60% if alcohol is excluded.41 Anxiolytics are most often

used in suicide attempts followed by antidepressants.42 Barbiturates used to be a common drug

used in overdoses, but because of the decline in prescriptions since the 1960s, overdoses from barbiturates are now rare.1The type of drug taken during a suicide attempt is important because

lethality varies for different drugs; for example, tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) are more toxic than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI).22,43 Some researchers recommend moving people to

less toxic medication to prevent fatal suicides, though TCAs are still commonly prescribed and switching is not always practical.34

Since overdose of psychotropic drugs contributes greatly to the overall societal burden of suicide attempts, it is important to understand why the medication prescribed to prevent

consequences of mental illness, including suicide attempts, is used in the attempt. We know some about what factors influence an individual to choose his or her preferred method in a fatal attempt, but we know less about factors influencing him or her to choose psychotropic medication.

Factors Influencing Method Choice

Research indicates that there are two important and necessary factors that influence which method an individual will use during a suicide attempt: physical access and cognitive access.12,34,44,45

These two factors have also been referred to as the availability and acceptability of methods,

respectively, where a method needs to both be easily accessible and perceived as an acceptable way to die in order for an individual to use it during a suicide attempt.46,47 Without both factors present

making the attempt.46 The next two sections will discuss these factors further and explain what is

known and gaps in knowledge for how these factors relate to choosing psychotropic medication during a suicide attempt.

Physical Access

Physical access is an important factor determining whether a person will use a specific

method. For obvious reasons, a person cannot use a method they do not have in their possession or a ot get a ess to. As e tio ed, a pe so is less likel to use a diffe e t ethod if the do t have access to their preferred method. Most of the research in this area has focused on the influence of physical access to lethal methods on method choice in individuals who died and most used the less valid ecological study design.13,48

Ecological studies indicate that cities with bridges and tall buildings have more people dying by intentionally falling/jumping compared to those living in rural areas or cities without tall

structures.49,50 Additionally, countries,51 regions,52,53 states,54 and cities55 with greater percentages of

the population owning firearms have higher rates of suicide deaths by firearm.31,46 Population-level

changes in physical access to methods over time also correlate with secular trends in methods used.12,17 For example, carbon monoxide poisoning from coal burning stoves was the most common

method of suicide in England until the country switched to gas burning stoves leading to steep declines in carbon monoxide-related suicide deaths.56

Some studies have also investigated the individual-level influence of physical access and method choice. For example, individuals with firearms in the home are nearly two to five times more likely to die by firearm suicide attempt compared to those without firearms in the home.57–61

Additionally individuals with jobs that increase the availability of a particular method are more likely to use that method than the general population, such as regular duty military personnel and farmers having higher risk of firearm suicide.62,63 Likewise, a study of people attempting suicide with

pesticide in Sri Lanka identified that having access to the poison was an important factor influencing their choice.64

Similar relationships were seen between physical access to over-the-counter paracetamol (acetaminophen) and use in suicide attempts in the UK.65,66 Of note, after legislation in the 1990s

that both limited the number of paracetamol tablets that could be sold at a time and required medication to be sold in blister packs, paracetamol suicides and suicide attempts decreased.12 Thus,

limitations to physical access of desirable methods, can have impacts on suicide attempts using that method.

While still an emerging field, the influence of physical access on method choice is logical and well supported. The influence of physical access to psychotropic medication and method choice has also been studied, but primarily with ecologic study design and not thoroughly in the United States. Prescribed Access and Psychotropic Medication

One measure of physical access, a focus of this dissertation, is prescribed access. Prescribed access refers to having physical access through filling a prescription from a clinician. The influence of prescribed access on method choice in an attempt might differ from having access to medication through a friend or family member, or from the illicit purchase of medication on the black market.

Several international studies, mostly in Scandinavian countries, have shown strong ecological relationships between prescribed access to psychotropic medication, via prescribing trends, and suicide deaths and/or attempts by psychotropic drugs. Many of these studies identified a positive correlation between prescribing patterns of specific classes of drugs and their use to carry out a suicide attempt.17–19,67 This relationship appeared especially strong with barbiturates,68–70 but

relationships have also been seen with anxiolytic, antidepressant, and antipsychotic

medication.19,68,71,72 A few studies found that prescribing patterns for less lethal medication (e.g.,

the conclusion that these might be more effective at preventing suicide73,74; however, it is not clear

if there was, instead, an increase in non-lethal suicide attempts using SSRIs in these populations since this research was only focused on suicide deaths.

Additionally, there have been a few studies that investigated individual-level access to psychotropic drugs and their use in suicide attempts.20 Some studies used occupation as a proxy for

general physical access, with one finding that nurses, doctors, and pharmacists were 3-5 times more likely to use poisoning than other employed people.21 Another study found that physicians dying of

suicide were more likely to use medication, with the most common medication being barbiturates. The same study found that a larger proportion of female physicians use antidepressants or

analgesics in suicides.75

In contrast, several studies evaluated the proportion of individuals using psychotropic medication in non-fatal suicide attempts who had prescribed access to psychotropic

medication.20,22–26 These studies indicated that most individuals using a psychotropic drug to

overdose were prescribed the drug. For example, Buykx et al. found that in a Melbourne emergency depa t e t, % of edi atio o e doses e e p es i ed the patie t s do to .23 A study in

Japan by Okumura et al. found that most patients who overdosed received a prescription at least 90 days prior to the overdose.26 However, no studies in the United States have investigated how

prescribed access to a psychotropic drug influences the choice of that medication in a suicide attempt. Also, no studies have contrasted how a prescription for psychotropic medication influences use of psychotropic medication versus another method in a suicide attempt.

Further, few studies have measured the influence of prescribed access to medication and method choice for different psychotropic drug classes. As mentioned, the ecological studies indicate that there is a positive correlation between all psychotropic drug classes and suicide attempts with that same drug group, except for the unclear relationship of SSRI use. One study in Ireland found

that for all drug overdose suicide attempts, 90% of those using antipsychotic medication had a prescription for that drug, 72% for barbiturates, 72% for antidepressants, and 61% for anxiolytics.25

However, this has not been investigated in the United States.

In conclusion, there is strong indication that individuals using a psychotropic drug during a suicide attempt were likely to have prescribed access to that drug, with evidence from both ecological and individual-level studies. However, no study has explored how prescribed access to medication might influence the choice of method. In other words, we are not sure how having a psychotropic prescription influences the actual choice of using that psychotropic drug compared to another drug or different method entirely. Also, an important factor in the method decision-making process has been excluded from the aforementioned studies: cognitive access. This factor needs to be explored because having physical access to a method does not guarantee a person with suicidal intent will use that method during a suicide attempt.

Cognitive Access

Cognitive access refers to how comfortable, familiar, or acceptable a method is to an individual attempting suicide.12,76 The influence of cognitive access is inherently more difficult to

study than physical access; however many population-level factors are implicated in influencing cognitive access to methods and explaining differences in the distribution of methods used in different countries, such as culture, news reporting, or other social factors.77–80

Research indicates that an individual will not use a method that he or she deems unacceptable even if he or she has physical access to that method.12,46 Ecologically, the relative popularity of

different methods can indicate differences in how acceptable a method is in different populations. The rise in carbon monoxide poisoning in Beijing and other Asian countries is a prime example of changing cognitive access. Carbon monoxide was not a common method for suicidal acts in Beijing until a news story was published about a woman who used this method.12 This article not only

explained how the woman carried out the act, but also described the death in a manner that indicated it was a peaceful way to die. Within a few months of this story, carbon monoxide

poisoning was the 3rd most common method of suicidal acts in Beijing and became drastically more

common in other Asian countries.62,81,82 Physical access to coal and other fuel that create carbon

monoxide was widely available, but it required the population awareness of how to carry out this method in a suicide attempt and the acceptability of carbon monoxide as a method, in order for it to be used widely.

Studying the influence of cognitive access on method choice is inherently difficult on the individual level. A few studies have used qualitative interviews of survivors of non-lethal suicide attempts to understand factors that influence cognitive access in individuals.64,76,80,83,84 For example,

Biddle et al., in a study of 20 survivors of suicide attempts, found that hanging was the preferred method because they expected it to be painless, would not damage their body, or traumatize those who would find them.76 Conversely, a different qualitative study in Iranian women surviving

self-immolation suicide attempts reported they chose that method because it represented their pain and suffering in their family or marriages.83

Cognitive Access and Psychotropic Medication

No studies are known to have investigated the influence of cognitive access on using

psychotropic medication. Cognitive access to psychotropic medication on the population level could e i flue ed a ultu e that alues the idea of a al a d uiet death. “i ila l , sui idal

individuals might determine psychotropic medication to be acceptable because they idealize a death they expect to be like falling asleep. In individuals already taking medication, they are already familiar with the medication and how it makes their body feel, so taking a lot of that medication might be preferred to a different drug or different method.

Other Factors

Several other factors have been identified to have strong influence on method choice for many methods, including poisoning. None of the following factors have been explored in relation to use of psychotropic medication in suicide attempts.

Demographic

Differences in method choice by gender and age are well established in the literature. Gender is strongly related to method choice with men more commonly choosing more lethal methods, such as firearms, in a suicide attempt.49,85 Women, on the other hand are more likely to attempt suicide, but

more regularly choose less lethal methods, predominantly poisoning.86 Exploring modification by

gender would inform whether having physical access to medication increases the likelihood that women will choose psychotropic medication in a suicide attempt more than men.

Age is another important factor in method choice. Older populations are more likely to choose more lethal methods.61 One U.S. study found that the mean age of self-poisoning victims was 30,

with ages 13-29 having the highest prevalence of self-poisoning.41 Another study in Australia found

that individuals younger than 45 were more likely to use psychotropic drugs in a suicide attempt, while less likely to be prescribed psychotropic medication.37 However, the influence of physical

access on choosing a psychotropic drug in a suicide attempt for different age groups has not been described.

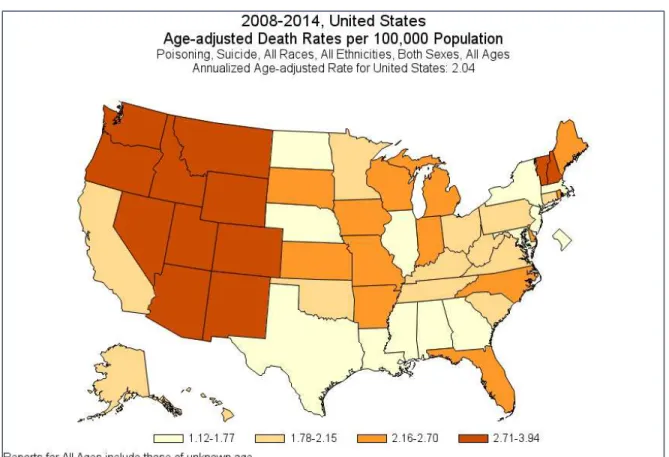

Geography, or where a person lives, is strongly related to both risk of suicide and method choice. National and international studies have identified different distributions of suicide and suicide behaviors between different countries and different geographies within a country. In fact, many studies have identified that on every level of geography investigated (city, county, state), suicide and suicide attempt risk differs depending on where a person lives.49-58 Firearm suicides are

based on geography in the United States are unclear. There appear to be differences in rates of poisoning deaths based on geography in the United States, with the highest rates in the West and Northeast (Figure 2.3).1 More research is needed to understand the differences in method choice

based on geography, and how where a person lives could influence the relationship between prescribed access and method choice of psychotropic medication.

Figure 2.3: Age-adjusted distribution of poisoning suicide mortality rate in the United States, 2008-2014

Days’ Supply

Limiting physical access to a method has been shown to decrease risk of suicide attempts12,13;

however, its influence on method selection has not been extensively studied. This is especially true for the influence of limiting physical access to psychotropic medication. With increases in individuals

filling several months of a prescription at a time through mail-order services,87 it is not clear if having

more or less medication at a time influences method choice in a suicide attempt, although more pharmacists see a 30 day supply as appropriate.88

Comfort with Medication

An individual who is comfortable with a medication prescribed to him or her might prefer using that medication in a suicide attempt compared to other methods. Individuals on medication for a longer period could be comfortable with the medication and more likely to choose a

psychotropic drug in a suicide attempt. Regularity of refills will be an interesting measure to look at because research on the efficacy of psychotropic medication indicates that better adherence (or higher regularity of refills) reduces risk of an individual attempting suicide.89 More regular refills

could indicate a person is comfortable with their medication and is familiar with taking it and acquiring it regularly. Likewise, an individual who is regularly refilling psychotropic medication could also be stockpiling the medication to make a suicide attempt.

Means Safety

Suicide can be an impulsive act and not having access to desired methods can make all the difference in preventing an attempt. Means safety is a broad umbrella term for interventions focused on restricting or preventing access to common methods used in suicides. It has been identified as one of the most effective way to prevent suicide, because it targets physical access to methods to which individuals might be at higher risk of having cognitive access. Means safety interventions can be targeted at both the individual level through clinical interventions or at the population level with policy interventions. Many means safety approaches have been described already in this chapter.

In other countries, many effective policy approaches have been taken to decrease access to poisoning methods used in suicide attempts. In Taiwan, the simple act of mandating that stores

move charcoal bags off the shelves where anyone could access them to locked shelves resulted in a 30% reduction in charcoal burning suicides.90 In Sri Lanka, where pesticide suicides were common,

policies restricting sales of particularly lethal pesticides resulted in a 50% reduction in the suicide rate.91 For medication, blister packs have been especially effective in preventing paracetamol (or

acetaminophen) and salicylate suicides in the United Kingdom, reducing suicides with these drugs by 40% after four years.92,93

Meanwhile, in the United States, there has not been effective policy reducing access to

poisoning methods, however there have been focused interventions targeting high risk populations. For example, there has been increasing work in infusing means safety into clinical conversations with Counseling in Access to Lethal Means (CALM) Trainings for clinicians to reduce access to firearms and medications for youth at-risk of suicide.94,95

There is a growing focus on means safety interventions to complement psychotherapy and other traditional therapies to prevent suicide attempts.96 It is still unclear if removing one method

prevents the use of another, perhaps less lethal, method,89,97 but there is evidence that a

multi-faceted approach is needed to move the needle on the suicide epidemic.3

Conclusion

Understanding factors influencing method choice in a suicide attempt is an important and emerging area of research. Little is known about factors that influence individuals to use

psychotropic medication in a suicide attempt, but prescribed access appears to be an important factor worth exploring further. Method choice research can inform means safety interventions, which have proven the most effective method in delaying or preventing a suicide attempt. This dissertation explored the influence of prescribed access to and use of psychotropic medication in an attempt in a population of individuals who attempted suicide, sampled from the largest national insurance claims database.

CHAPTER III

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study used case-control study design and insurance claims data to identify a population of individuals who attempted suicide and examine whether the individuals using psychotropic medication in a suicide attempt were more likely to have recently filled a prescription for a psychotropic drug compared to those using other methods in their suicide attempt. CHAPTER IV explores all psychotropic drugs combined, differences by psychotropic drug group, and the influence of prescription-related factors in a subpopulation of individuals with prescribed access. In CHAPTER V, modification of this effect by important demographic factors is examined.

Study Population

The study population consisted of all individuals with a suicide attempt identified from the PharMetrics Legacy Health Plans Claims Data, the largest patient-centric database of longitudinal and integrated medical, facility, and pharmacy claims data in the United States. The full limited dataset represents over 65 million patients on over 80 health plans across the country, consisting of fully adjudicated medical and pharmaceutical claims.98 Health plans included Medicare and

Medicaid, HMOs, and other major commercial plans. Patients included in the dataset have the same age and gender distribution as the US population, though this dataset was not necessarily

representative of those without health insurance. The study population was identified from a Mental Health cohort that includes all patients in the PharMetrics dataset with at least one claim with a mental health diagnosis, a filled prescription for antidepressants, or diagnosis code indicating a suicide attempt in 2006-2013.

The database provided health plan enrollment information; details of medical encounters at outpatient, emergency department or inpatient facilities; and medication information for each filled prescription. Each medical encounter included up to 4 diagnosis codes, with external cause of injury

codes (E-codes) for suicide and self-inflicted injury used to define the population of patients with a suicide attempt. PharMetrics included year of birth, gender, region of residence, and insurance information, but did not include other demographic information such as race or socioeconomic status.

This study was determined to be Not Human Subject Research by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board Protocol 16-1011.

Description of Data

The PharMetrics Dataset had 3 sub files with linking variables shaded in Table 3.1: a patient file, a claims file, and a drug file. More in-depth information for important variables is provided later in the chapter, but they will be briefly introduced and explained in the following section.

Table 3.1: Layout of variables included in each of the 3 PharMetrics files. Shaded fields indicate variables that link datasets.

Patient File Claims File Medications File

Unique Patient ID Unique Patient ID General Product Identifier Code Year of Birth Prescriptions Filled Strength

Gender National Drug Code National Drug Code

Region of Residence Days Supplied Drug Class Type of Insurance Place of Service Brand Name Month Health Plan Enrollment Procedures Generic Name

Provider Specialty Service Dates Diagnosis Codes

Patient file

The patient file included one record of data for each patient. Demographic information about each patient was provided in this file including year of birth, gender, region of residence (West, “outh, Mid est, No theast , t pe of i su a e Co e ial Pla , “tate Child e s Health I su a e Plan (CHIP), Medicaid, Medicare, Self-insured, other/unknown), and monthly health plan enrollment string. The enrollment string indicated for each month in the dataset whether the patient was enrolled in the health plan for every given month in the time frame.

Claims File

The claims file provided information for every claim billed to the insurance carrier, with each record in the dataset representing one claim. Every claim was linked to the patient file by the unique patient ID.

Each record of the claims file could either represent a medical encounter (outpatient, emergency department (ED), or inpatient (IP)) or a prescription filled at an outpatient pharmacy. Medical encounters described where the encounter occurred, diagnosis codes, procedure codes, provider specialty, and service dates. Prescriptions filled by patients included the National Drug Code (NDC) and the number of days supplied. The NDC is a random code provided for each drug that specifies information on the drug group, brand, and strength.

Variables from the claims file provided the most consequential data to the study, with diagnostic codes and NDC used to select the population and define outcome, exposure, covariates, and

prescription-related factors. ICD-9 CM diagnostic codes provided in the claims file for each claim to insurance was a central variable for this study. Every medical encounter claim in the ED, IP, or other health care facility included up to 4 diagnostic codes.

Medications File

One medication could have several NDCs which change from year-to-year as minor alterations to the formula occur. Thus, the NDC for each filled medication was linked with the medication file to identify a General Product Identifier (GPI) code - an alternate hierarchical drug classification system. The first 2 digits in the 14-digit GPI code were used to identify individuals with prescribed access to psychotropic medication and then stratify them into the specific drug groups.

Variables used in this study were either taken directly from PharMetrics or calculated from existing measures in the dataset. Important variables are described in more detail in the following sections.

Sample Selection

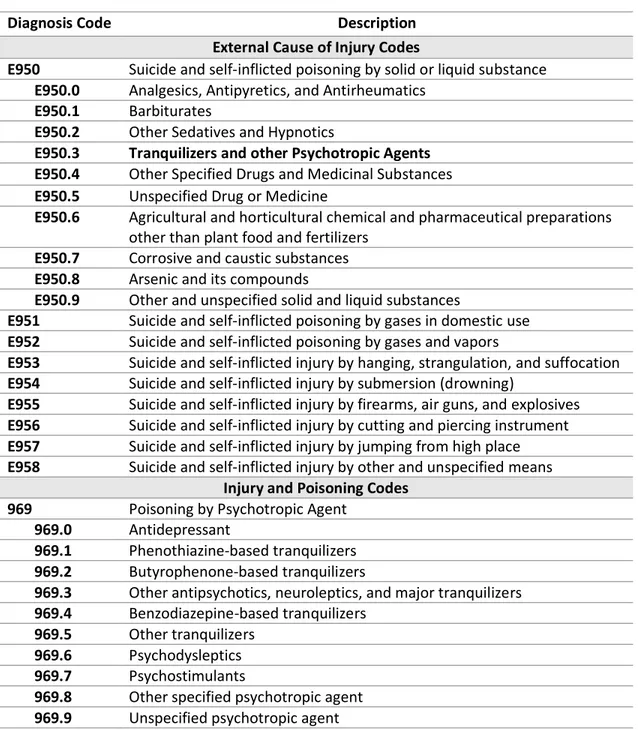

Only patients in PharMetrics with an insurance claim from an ED or IP hospital stay for which the diagnosis codes indicated a suicide attempt were included in this study. Qualifying ICD-9 CM

External Cause of Injury Codes (E-codes) (Table 3.2) were used to identify these individuals from the available diagnosis codes on each medical claim. The E950-E958 codes indicate suicide and self-inflicted injury with the last digit specifying the method used in the attempt (Table 3.2). Individuals with one of these codes were considered for the study sample.

The first occurrence of a suicide attempt for each eligible patient between the years 2006-2013 was considered the index attempt. To reduce the likelihood that the event was a reattempt, only individuals enrolled in their insurance program at least 1 year prior to the index attempt were included, as reattempt risk is highest within the first year after an attempt.30 Also, participants

younger than 18 years at the time of their attempt were excluded since prescribing psychotropics for youth is different than for adults.99

Code E959 indicates patients treated for late effects (or sequelae) of a previous self-inflicted injury but not a current attempt, therefore only E950-E958 codes were used in this study and patients with an E959 code present as a diagnosis code for the index attempt were excluded.

Summary of inclusion criteria:

1. E950-E958 diagnosis code, without the presence of E959 Code on initial claim for attempt 2. Suicide attempt seen at an ED or IP facility type

3. ea of o ti uous e oll e t p io to ea liest suicide attempt 4. ea s old at ti e of ea liest sui ide atte pt

5. No missing 4th digit in the E950 code, unless there is an additional E-code or 969 code

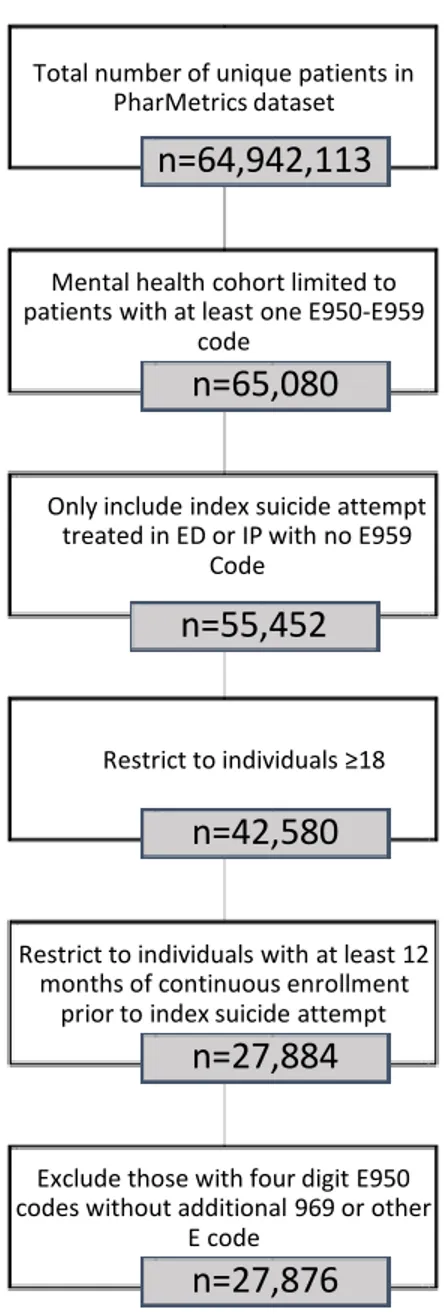

Applying inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in a study population of 27,876 individuals from the 65,080 who attempted suicide (Figure 3.1).

Table 3.2: Relevant Diagnosis Codes for determining case status.

Diagnosis Code Description

External Cause of Injury Codes

E950 Suicide and self-inflicted poisoning by solid or liquid substance E950.0 Analgesics, Antipyretics, and Antirheumatics

E950.1 Barbiturates

E950.2 Other Sedatives and Hypnotics

E950.3 Tranquilizers and other Psychotropic Agents E950.4 Other Specified Drugs and Medicinal Substances E950.5 Unspecified Drug or Medicine

E950.6 Agricultural and horticultural chemical and pharmaceutical preparations other than plant food and fertilizers

E950.7 Corrosive and caustic substances E950.8 Arsenic and its compounds

E950.9 Other and unspecified solid and liquid substances

E951 Suicide and self-inflicted poisoning by gases in domestic use E952 Suicide and self-inflicted poisoning by gases and vapors

E953 Suicide and self-inflicted injury by hanging, strangulation, and suffocation E954 Suicide and self-inflicted injury by submersion (drowning)

E955 Suicide and self-inflicted injury by firearms, air guns, and explosives E956 Suicide and self-inflicted injury by cutting and piercing instrument E957 Suicide and self-inflicted injury by jumping from high place E958 Suicide and self-inflicted injury by other and unspecified means

Injury and Poisoning Codes 969 Poisoning by Psychotropic Agent

969.0 Antidepressant

969.1 Phenothiazine-based tranquilizers 969.2 Butyrophenone-based tranquilizers

969.3 Other antipsychotics, neuroleptics, and major tranquilizers 969.4 Benzodiazepine-based tranquilizers

969.5 Other tranquilizers 969.6 Psychodysleptics 969.7 Psychostimulants

969.8 Other specified psychotropic agent 969.9 Unspecified psychotropic agent

Figure 3.2: Population sample for each step of the population selection process. The final population for analysis was 27,876

Important Measures Defining Cases and Controls

Case and control status was defined based on information regarding method used during suicide attempt provided by diagnosis codes. Initially, there were two control groups defined: 1) individuals using non-psychotropic medication in a suicide attempt and 2) individuals using all other methods in a suicide attempt. Both E-codes and Injury and Poisoning codes (Nature of Injury or N-codes) were

Total number of unique patients in PharMetrics dataset

n=64,942,113

Mental health cohort limited to patients with at least one E950-E959

code

n=65,080

Only include index suicide attempt treated in ED or IP with no E959

Code

n=55,452

‘est i t to i di iduals

n=42,580

Restrict to individuals with at least 12 months of continuous enrollment

prior to index suicide attempt

n=27,884

Exclude those with four digit E950 codes without additional 969 or other

E code

n=27,876

used to distinguish cases and the two control groups. Cases were first defined as individuals using any psychotropic drug in a suicide, and then as individuals using any of four possible specific psychotropic types (i.e., anxiolytic, antidepressant, antipsychotic/mood stabilizer, and stimulant) based on whether there was indication each specific drug group was used in a suicide attempt (Table 3.3).

Diagnostic codes E950.0-E950.5 indicate that a drug or medicinal substance was used in the attempt, with E950.3 used for all psychotropic drugs (Table 3.2). Injury and Poisoning codes (ICD-9 800-999) provide more information about an injury or poisoning for medical billing purposes. When a patient is harmed by a poison, poisoning codes provide information about specific chemicals involved, with 960-979 indicating poisoning by drugs, medicinal, or biologic substance. Since the population was already limited to those who attempted suicide, the 969.X psychotropic poisoning code (Table 3.2) was also used to identify cases even without an accompanying E950.3 code. Thus, individuals with E950.3 codes or any 969 code were defined as cases. In sensitivity analysis, an alternate case definition was considered where only individuals with an E950.3 code were included, regardless of the presence of a 969 code.

The first control group was defined based on the presence of at least one E-code that indicated drug poisoning not from a psychotropic drug – E950.0, E950.1, E950.2, E950.4, E950.5. The second control group included individuals with all other E-codes for suicide attempts– E950.5-E950.9 and E951-E958, but not E-codes for psychotropic or non-psychotropic medication. Five different outcome variables were created (any psychotropic, anxiolytic, antidepressant, antipsychotic/mood stabilizer, stimulant), with 3 levels each (case, control 1, and control 2).

The case definition used for Aim 3 was based on results from Aims 1 and 2 where differences in the relationship by specific psychotropic drug indicated that it was important to continue looking for differences by specific psychotropic drug type.

26

Table 3.3: Description of important variables, including outcome, exposure, prescription-related factors, modifiers, and other covariates.

Measure Criteria or Calculation Explanation

Defining Outcome – Diagnosis Codes (E-codes and Injury and Poisoning Codes)

Case Diagnosis code= E950.3 and/or 969.X

Presence of either diagnosis code in claim for attempt indicated a case

Anxiolytic Diagnosis code=969.4, 969.5

Antidepressant Diagnosis code=969.0

Antipsychotic/Mood Stabilizer Diagnosis code=969.1, 969.2, 969.3

Stimulant Diagnosis code=969.7

Other/Unknown

Diagnosis code=E950.3 and no 969.X, 969, 969.6, 969.8, 969.9

If E950.3 was present with no accompanying 969.X code, or other code that did not specify the drug groups of interest

Control 1 Diagnosis code=E950.0, E950.1,

E950.2, E950.4, E950.5

Other drug poisoning E-codes. Some psychotropic drugs may be included with E950.5

Control 2

Diagnosis code=E950.5, E950.6, E950.7, E950.8, E950.9, E951, E952, E953, E954, E955, E956, E957, E958

All other self-harm E-codes Defining Exposure –Prescribed Access

Filled Psychotropic GPI code= 57, 58, 59, 61

Prescription filled in 3 months prior to attempt for any of these GPI codes

Anxiolytic GPI code= 57

Antidepressant GPI code= 58

Antipsychotic/Mood Stabilizer GPI code= 59

Stimulant GPI code= 61

Defining Exposure –Prescription-Related Factors

Average Days’ Supply Total days supplied/number of fills Only included prescriptions filled within 365 days prior to the attempt

Length of Access (Last fill date + last days supplied) – earliest fill date

Only included prescriptions filled within 365 days prior to the attempt

Regularity of Refills Total days supplied/(length of access)

Medication Possession Ratio, only included prescriptions filled within 365 days prior to the attempt

27

Ta le 3.3 o t’d

Measure Criteria or Calculation Explanation

Defining Covariates

Year of attempt 2006-2013 Extracted from service date of index attempt

Gender Male or Female Gender defined in patient file

Age Event year minus birth year Calculated from Service date in claim file and year of birth in patient file. Stratified into the following categories 18-24 Years, 25-44 Years, 45-64 Years, 65+ Years

Region of Residence East, South, Midwest, and West Census Bureau 4-region extracted from patient file Insurance Type Commercial, Medicaid, Medicare

Risk, Self-Insured, Medicare Cost, Missing/unknown

Enrollment string in the patient file indicates payer type as one of the following:

Psychiatric Diagnosis

Schizophrenia Diagnosis code= 295

Diagnosis codes were used to determine if there was diagnosis of mental illness in the year prior to the suicide attempt

Mania Diagnosis code= 296.0 or 296.1

Depression Diagnosis code= 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311

Bipolar Diagnosis code= 296.4-296.8

Anxiety Diagnosis code= 300

Substance Use Disorder Diagnosis code= 303-305 Other Mental Illness Diagnosis code= 297-299, 301, or 302

Multiple Methods Count of unique E-codes Number of unique E-codes present for IP or ED stay to indicated if multiple methods were used in the suicide attempt

Severity of Mental Illness

Comorbid Mental Illnesses Count of unique psychiatric diagnoses (0,1,2, and 3)

Number of distinct psychiatric diagnosis codes in year prior to suicide attempt

Inpatient Stays (1) At least 1 hospital stay with mental health code 1 year prior to attempt

Presence of inpatient hospital stay with an accompanying psychiatric diagnosis code in year prior to suicide attempt

Defining Exposure

The main exposure for most analyses was prescribed access to psychotropic medication. In a subpopulation of those with prescribed access, prescription-related exposures were tested. Measurements for both are described.

Prescribed Access

Like case status definitions, there were five different exposure measures defined in this study. The GPI codes shown in Table 3.3 were used to create five dichotomous variables for each of the drug groups indicating whether they filled at least one prescription for that drug group in the 90 days prior to the suicide attempt. This definition included both medications filled during the prior 90 days, as well as medications filled prior to the 90 da s ut ith a o e lappi g da s suppl . Fo ea h individual and each specific drug group, if he or she filled a prescription for that medication, then the variable was coded as 1, otherwise the variable was coded as 0. Sensitivity analysis explored longer exposure windows, which ultimately did not impact results, so only results using the acute (90 day) window were reported. Changes in prescribing habits and off-label use of medication have led to certain non-psychotropic medications such as anticonvulsant drugs being used to treat mental illness, so cases might not include all possible psychotropic drugs.100 However, the 4 drug groups

selected represent the majority of medication with psychotropic benefits.

Defining Prescription-Related Exposures

In a subpopulation of those with prescribed access, associations of several prescription-related factors with method choice were tested.

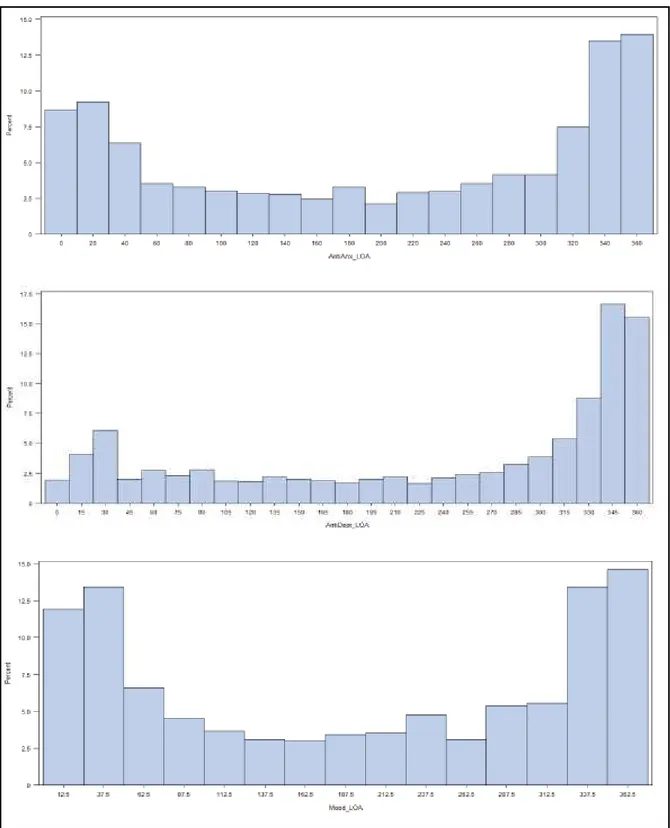

A erage Days’ Supply. The a e age da s suppl as a easu e of the amount of medication on ha d Ta le . . The da s suppl a ia le p o ided i the lai s dataset fo ea h filled prescription was used to calculate the average days supply in the year prior to suicide attempt. This variable was first considered as continuous, but was stratified into 2 categories after investigating the distribution

for different specific psychotropic drug types (Figure 3.3). Most values were expected to be near 30 days or 90 days, however there were large differences between drug types and many individuals with prescribed access to anxiolytic medication involving a a e age da s supply <30 compared to antidepressant and antipsychotic/mood stabilizer prescriptions which were more commonly 30 days. The cutoff of 15 days was used for consistency across drug types and to have enough individuals in each category.

Length of Access. The length of access variable measured how long since the earliest prescription

filled for each specific drug type prior to the index suicide attempt. Patients prescribed different medications within the same drug group were considered to have access to the same drug-type over the interval. The duration of claims for each psychotropic drug group was calculated up to 1 year prior to the index attempt. Initially, I intended to stratify the exposure into three categories: <90, 90-180, and 181-365 days. However, after investigating the distribution of variables (Figure 3.4), I observed a bimodal distribution around 180 days. The 90-180 group was too small to calculate meaningful differences, so the variable was collapsed into two groups: < da s a d da s. This stratification provided a comparison for the influence of shorter versus longer prescribed access to each specific drug on the likelihood of using that specific psychotropic drug type in a suicide attempt.

Regularity of Refills. The regularity of refills construct described how well an individual

maintained medication on hand for the one year period prior to the suicide attempt and is a

measure of adherence in secondary datasets.101 It was calculated as the medication possession ratio

MP‘ hi h is the total u e of da s suppl i the o e-year period divided by the total number of days within that study period (Table 3.3). This a ia le as st atified as < . a d . as

Figure 3.3: Histogra s of average days’ supply of anxiolytic, antidepressant, and

antipsychotic/mood stabilizer medication for individuals with prescribed access to respective medication.

Figure 3.4: Histograms of length of access to anxiolytic, antidepressant, and antipsychotic/mood stabilizer medication for individuals with prescribed access to the respective medication.

Figure 3.5: Histograms of medication possession ratio (MPR) for anxiolytic, antidepressant, and antipsychotic/mood stabilizer medication in individuals with prescribed access to the respective

1.00 for the year prior to the attempt, though there was enough variation to measure differences between groups with higher and lower MPR.

Other Measures

Several possible confounders were evaluated for inclusion in models exploring the exposure-outcome relationship. The full list and description of these variables is described in Table 3.3. Important demographic variables available or calculated in the patient file were gender, insurance type, age at suicide attempt, year of attempt, and region of residence. Age, gender, and geography have been identified as important factors in method choice, while type of insurance is the best measure of socioeconomic status that is available in the dataset. The year of attempt was considered because physician prescribing behaviors could change from year to year.

Several variables describing mental illness and the severity of mental illness were also

considered as covariates. Mental illness diagnosis codes (295-305 or 311) present in the year prior to the suicide attempt were used to define 6 psychiatric diagnosis variables (i.e., schizophrenia, mania, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, and other). Each variable was dichotomous with a 1 indicating the diagnosis was recorded at least once during the year prior to the attempt, and a 0 if it was not. Severity of mental illness is not specifically denoted in claims data, but two different proxies were used to capture this measure: (1) comorbid mental illnesses and (2) an inpatient hospitalization due to mental illness.103 Comorbid mental illnesses were calculated as a

count of unique psychiatric diagnoses (schizophrenia, mania, depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, substance use disorder, or other) in the year prior to the suicide attempt. The presence of an inpatient hospitalization stay with a psychiatric diagnosis code present in the year prior to the suicide attempt was also used to indicate relative severity of mental illness. Finally, an indicator of multiple methods used in the suicide attempt was examined, calculated as the number of unique suicide attempt E-codes present in the claims file for each suicide attempt.

Analysis

Multinomial logistic regression was originally considered for this analysis because of the categorical distribution of the outcome with 3 mutually exclusive levels: (1) case, (2) control 1, and (3) control 2. However, since the relationship of exposure between cases and control 1 compared to cases versus control 2 were not different, the control groups were combined, thus creating a dichotomous outcome. Logistic regression was therefore used for analysis. The next few sections first discuss logistic regression, and then describe the assumptions in expanding the model by using multinomial logistic regression. Analytic approach and discussion of modification follow.

Logistic Regression

Logistic regression is the predominant method used to analyze case control study data or other data with a dichotomous outcome because the assumptions of linear regression (e.g., linear association between exposure, normally distributed outcome) are not met.104 Instead, logistic

regression uses a logit – �� �

−� – assumption for analysis using Equation 3.1 to describe the resulting model.

�� �−� = � + � � + ⋯ + ���� Equation 3.1

In this model, � is the probability of an event occurring, �

−� is the odds of an event occurring, and � represents the coefficient of the relationship between the variable � and the logit, adjusted for all other variables in the model. The reported odds ratio (OR) for a given �-coefficient is calculated as ��= ��.

To assure good model fit the following assumptions were tested: (1) independence of errors, (2) linearity of the logit for continuous independent variables, (3) absence of multicollinearity among independent variables, and (4) lack of strongly influential outliers.105

To meet Assumption 1 all the observations (i.e., persons with index suicide attempt) had to be independent and uncorrelated. For this study, absolute independence of observations could not be assured and is a limitation of the study since a patient leaving one insurance plan and joining another one that also provided data to the PharMetrics dataset would have two unique patient IDs for their time in each plan, even though they were not unique individuals. It was impossible to link patients with the limited data provided. We limited the possibility that an individual would be included twice by requiring a year of continuous enrollment prior to the index suicide attempt; however, with an annual 15-17% turnover rate in insurance plans we could not guarantee absolute independence of observations.106,107 We cannot quantify the likelihood of this occurring, but due to

the large sample, we did not expect this have a major impact on the final model fit.

Assumption 2 required a linear relationship between continuous independent variables and the logit transformed probability of the outcome. For all continuous variables, the logit of the estimated probabilities for each subject versus age categorized into quintiles and the mean logit of

probabilities for each level was graphed to ensure a reasonably linear relationship. If the output was non-linear, the covariate was recoded into a discrete variable with logical cut points. Age was the only variable tested and was categorized because there was not a linear increase in the logit.

In Assumption 3, the variables cannot be strongly correlated with each other, or multicollinear. Multicollinearity of variables can inflate the standard error, making it difficult to detect individual significant relationships that exist.105 In this study, correlation of covariates was tested for all

variables of interest. Variables with a Spearma s o elatio of . were identified and the covariate more strongly related to the outcome in the model was included. Measures of severity of mental illness were strongly correlated with the primary exposure measures, so neither severity variable was included.

Finally, Assumption 4 required that there were no points or groups of points that were major outliers in their covariate patterns, impacting the calculated association. The DFBETAS function in PROC LOGISTIC was used to test the influence of each observation on the beta coefficient for each covariate used in each final model to ensure that each observation did not change the magnitude by more than 20%. No issues were identified.

Multinomial Logistic Regression

Multinomial logistic regression was originally considered for all analysis. Multinomial logistic regression builds on the model and assumptions of logistic regression but expands to allow for a categorical outcome with more than two categories. An important assumption of multinomial logistic regression is the independence of irrelevant alternatives, where excluding or including any of the outcome categories should not have a strong influence on the association already measured. This was confirmed by modeling the outcomes separately and together to ensure outcomes included were not significantly altering findings.

In multinomial regression, the cases were designated as the reference group to estimate the adjusted odds ratios of interest. The modeled outcome was the odds of being exposed in each control group versus the case groups; the inverse of these odds ratios and confidence intervals was reported to estimate the odds of being exposed in cases versus each control group. However, after first modeling aims 1 and 2 using multinomial logistic regression, the association was not different between cases and control 1 versus control 2. Therefore, the two control groups were combined and logistic regression was used for all analysis.

Modification

Modification exists when a third variable creates heterogeneity in the association between the exposure and outcome of interest.104 In practice, testing for modification in important relationships

individuals with depression). Interventions focused on high risk groups can have a bigger impact while investing fewer resources. Additionally, identifying important modifiers can identify new potential areas for intervention or policy changes (e.g., individuals receiving larger single fills of medication). Possible modifiers in the relationship between prescribed access to psychotropic drugs and method choice in a suicide attempt were identified a priori.

Modification was tested in a logistic regression model using the interaction term, such as in Equation 3.2.

�� �−� = � + � � + � � + ���� � ∗ � Equation 3.2

where ���� represented the interaction term of � *� . Modification, while generally tested using an interaction term in regression modeling, is a distinct concept from interaction. Interaction is a statistical test that does not imply direction, where modification is intentional in testing whether the 3rd variable is the modifier in the effect-outcome relationship.108 The resulting output provided odds

ratios representing the association of the exposure and outcome at each level of a categorical modifier. A significant interaction term (p < 0.05) indicated that the association of outcome and exposure was significantly different for at least one level of the modifier.

Missing Data

Missing data can create major problems in epidemiological studies, especially in those using secondary data. Most statistical software drops individuals with a missing variable from models in analysis. Depending on the distribution of missing data for a variable, biased results can be a concern. There is less concern when data for a variable are missing completely at random since a random selection of individuals is dropped from the model, likely not resulting in biased findings. However, if data are missing not at random but based on another important factor (that is either directly measured or not), this could have major detrimental impacts on the findings, especially if missingness is related to the outcome or exposure.