J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

The Relationship Between Ownership Structure and Hostile

Takeovers in Sweden with an International Perspective

Master Thesis within Business Administration

Authors: Henrik Johnson

Daniel Josefsson

Tutors: Johan Eklund

Andreas Högberg Jönköping June 2011

Acknowledgements

The authors of this thesis would like to express our gratefulness to all people who have helped us during the process.

First of all we want to express our gratitude to our tutors Johan Eklund and Andreas Hög-berg for their valuable support and guidance. Without them this thesis would not have been possible.

We also want to thank the staff at Jönköping University Library for their knowledge and excellent service, especially Daniel Gunnarsson that helped us during the process of col-lecting data.

Finally, we would like to thank our fellow students who participated during seminars and provided us with constructive and continuous feedback.

______________________ _______________________

Henrik Johnson Daniel Josefsson

Master Thesis within Business Administration

Title: The Relationship Between Ownership Structure and Hostile

Takeovers in Sweden with an International Perspective

Authors: Henrik Johnson and Daniel Josefsson

Tutors: Johan Eklund and Andreas Högberg

Date: 2011-06-08

Keywords: Hostile takeovers; Ownership structure; Corporate governance;

Control enhancing mechanisms

Abstract

Background: Throughout the last century mergers and acquisitions have been

catego-rized by changes in the global economy. Globalization and changes in legislations has brought forward so called waves that are rooted in the market for the United States. Where the act of acquisitions can be divided into both friendly and hostile takeovers, history shows that hostile takeovers are frequent in the US but less evident in the Swedish market. As for Sweden the existence of control enhancing mechanisms are utilized to enable con-trol of a firm without owning a proportionate share of equity. While the trend of takeover activity is replicated elsewhere, the hostile aspect finds another route. The market for cor-porate control governs the hostile aspect where firms should be replaced with new manag-ers if agency problems arise between the management and the shareholdmanag-ers. Thus looking at Sweden, corporate governance issues and the establishment of national laws are of cer-tain importance.

Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to examine how the ownership structure in

Swe-dish listed companies impacts on the occurrence of hostile takeovers and what implications a potential change in the corporate governance structure would have on it. Moreover we intend to map Sweden internationally to give a broad picture of the research area.

Methodology: We have made use of a quantitative method for the empirical section and

thereafter derived conclusions through the hypothetico-deductive approach. For testing the outcome of hostile bids in Sweden, chi-square tests for independence have been conducted and in regards of an international comparison we have implemented a correlation analysis.

Conclusions: With the result at hand we concluded that the theory was partially aligned

with the empirical data. The market for corporate control is not fully efficient in Sweden. The reason for that is the multiple voting rights implemented in the target firms which im-pede the successfulness in replacing a management. The hostile bid frequency has increased over the years, mainly due to potential agency problems among target firms. But parallel to this, which in some regards contradicts theory, is that firms neglects the prevalent owner-ship structure in Sweden and acquires a foothold as to make their hostile acquisition. In re-gards of the empirical data, concentrated ownership solely does not harm the market for corporate control in Sweden. Internationally, the correlation between ownership concentra-tion and hostile bid frequencies proved to be negative where Sweden despite this attracts hostile acquirers.

Table of content

Acknowledgements ... i Abstract ... ii1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem discussion ... 2 1.2.1 Research question... 2 1.2.2 Sub- questions ... 3 1.3 Purpose ... 3 1.4 Outline ... 32

Methodology ... 4

2.1 Choice of subject ... 4 2.2 Quantitative method ... 4 2.3 Secondary data ... 52.4 The abductive and deductive approach ... 5

2.4.1 Doing management research ... 6

2.5 Validity and reliability ... 6

2.6 Objectivity ... 7

2.7 Empirical data gathering ... 7

3

Theoretical framework ... 9

3.1 Takeovers, not mergers ... 9

3.2 Friendly vs. hostile takeovers ... 9

3.3 Motives for acquisition ... 10

3.3.1 Economy of scale ... 11

3.3.2 Economy of scope ... 11

3.3.3 Transaction costs ... 12

3.4 Takeover activity... 12

3.4.1 Takeover activity in the US ... 12

3.4.2 Takeover activity in the EU ... 14

3.4.3 Takeover activity in Sweden ... 15

3.5 Swedish corporate law and EU Directive ... 17

3.5.1 Takeover regulations ... 17

3.5.2 Shareholder acceptance ... 18

3.5.3 The hostile aspect ... 19

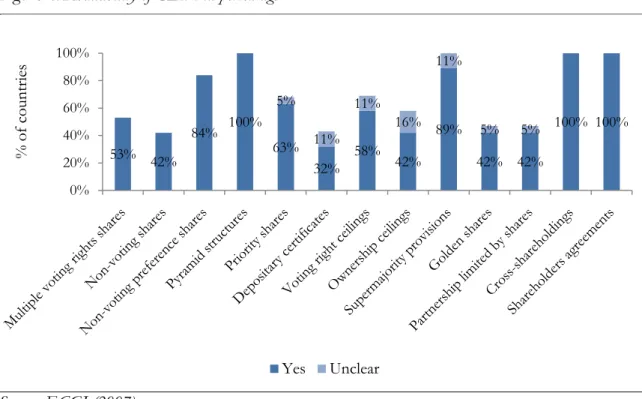

3.6 Control enhancing mechanisms ... 20

3.6.1 Definition of the different CEMs ... 20

3.6.2 CEMs in practice ... 22

3.6.3 The Swedish case ... 24

3.7 Corporate governance issues ... 25

3.7.1 Market for corporate control ... 26

3.7.2 Agency costs ... 26

3.8 Ownership and control ... 27

3.8.1 Dispersed ownership ... 27

3.8.2 Concentrated ownership ... 27

4

Empirical findings & international comparison ... 31

4.1 Hostile bids in Sweden ... 31

4.2 Chi-square test for independence ... 32

4.2.1 Multiple voting rights ... 33

4.2.2 Concentrated ownership ... 33

4.2.3 Origin of bidder ... 34

4.2.4 Foreign bids per year ... 35

4.3 International comparison ... 35

4.3.1 Hostile takeover bids – CEMs ... 36

4.3.2 Hostile takeover bids – Ownership Structure ... 38

5

Analysis ... 41

5.1 Hostile takeover activity ... 41

5.2 EU directives and regulations ... 42

5.3 Control enhancing mechanisms ... 43

5.4 Ownership and corporate control issues ... 43

5.5 The future of the Swedish model ... 44

6

Conclusions ... 46

6.1 Further research ... 46

6.2 Reflections ... 47

7

References ... 48

Appendices ... 52

Appendix 1 - Data gathering attempt ... 52

Appendix 2 - Chi-Square test for independence... 53

1 Introduction

The introductory section of this thesis will start to give the reader a background about hostile takeovers and the aspects related to the Swedish market, followed by the problem discussion that arises. We are further-more presenting our research questions in the area and outlining our purpose. A disposition of the thesis will finish the introduction.

1.1 Background

The mergers and acquisitions around the world have been for the last century categorized by changes in the global economy. Stemming from the globalization itself and the changes that occur on a juridical basis, what can be seen on this subject is that these changes arrives in so called waves. These changes are to a high degree attributable to the mergers and ac-quisitions that take place on the market in the United States. The seemingly determined ap-proach towards growth for companies through the overcoming of legal barriers finds it roots in the US. Ranging from the legislation of cartels and monopolies that were imple-mented in the 1890‟s and 1950‟s respectively (The Sherman Act and the Celler-Kefauver Amendment) US listed firms therefore found new ways of expanding through mergers and acquisitions. The latest result of this consistency of overcoming legislation can be seen by the creation of conglomerate mergers, which is a merger between two strategically unre-lated firms (Mueller, 2003). The act of mergers and acquisitions can also be divided into their type of nature. A takeover may be either friendly or hostile depending on the underly-ing motives that drive the engagement of such an acquisition (Morck, Shleifer & Vishny, 1988). Whereas the latter cause of action is highly evident in the US market (Mueller, 2003). What can be discerned from this fact and accepted norms is that the US pose a huge influ-ence on the rest of the world governing the financial market and hinflu-ence, the perceived benefits regarding takeovers. A natural conclusion to be drawn from this would thus be that the behaviour in the US is replicated on the Swedish financial markets. However, this does not seem to be the case.

In Sweden the corporate law is stricter than the widely used corporate law in the US, namely the Delaware General Corporation Law. The so called “race to the bottom” in the US, which implied that a majority of the states lowered their taxes and eased regulation in attempts to attract newly founded firms to incorporate their organization there, thus gain-ing income from tax payments, resulted in that firms eventually chose the state of Delaware (Frankel, 2005). 63 percent of the firms being among the Fortune 500 and 50 percent of the total firms on the New York Stock Exchange are registered in Delaware (State of Delaware, (2010). In Sweden there are legislative rules stating that if one purchases a suffi-cient amount of shares they have to bid for the rest of the shares as well, this is called the mandatory bid threshold and has recently been lowered to 30 percent. Impact arising from the Swedish behaviour in regards to how media presents takeover activities is also of value whereas a shift towards good market practice for shareholders may impede the initiative for takeovers given the historical fact that they seldom succeed (Global Legal Group, 2010; Papadopoulos, 2010).

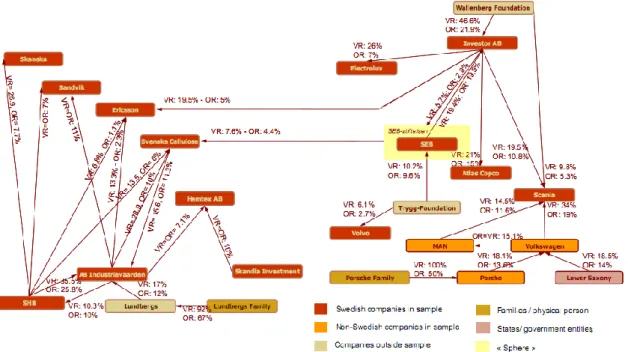

The control of a company is based on the amount of controlling shares the owner has. In Sweden there are a few dominating control enhancing mechanisms (CEMs). As in many other European countries, it is common for Swedish companies to make use of multiple voting rights shares. This means that ownership and control does not need to go hand in

hand since different shares have different voting rights. Another frequently used CEM in Sweden is pyramid structures which are when a family or a business holds a controlling stake in a company which in turn controls another company. This pyramid can continue in different steps to include more companies which in turn lead to a higher separation be-tween ownership and control. Because of the widespread use of these two control enhanc-ing mechanisms in combination of each other, controllenhanc-ing owners tends to be locked in for long time periods. This in turn leads to rising agency costs and a lack of corporate control which means that hostile takeovers are very rare at the Swedish market. The effect of lock in control may be further enhanced by cross-shareholdings i.e. that companies in a certain sphere has holdings in each other. There are two unique spheres in Sweden with a signifi-cant impact on the Swedish Stock Exchange, namely the SHB sphere and the Wallenberg sphere both utilizing these three CEMs (Henrekson & Jakobsson, 2008; Wiberg, 2008). A further note to this background is the occurrence of previous research on the subject of mergers and acquisitions in general, that heavily stems from the United States and United Kingdom and thus their financial markets respectively. The lack of having a Swedish focus regarding research articles on this area is something that raised our interest for this study. The outlined purpose where Sweden being the main focus is something that is not fre-quently examined and thus furthermore being something where we, with this thesis, hope to contribute to.

1.2 Problem discussion

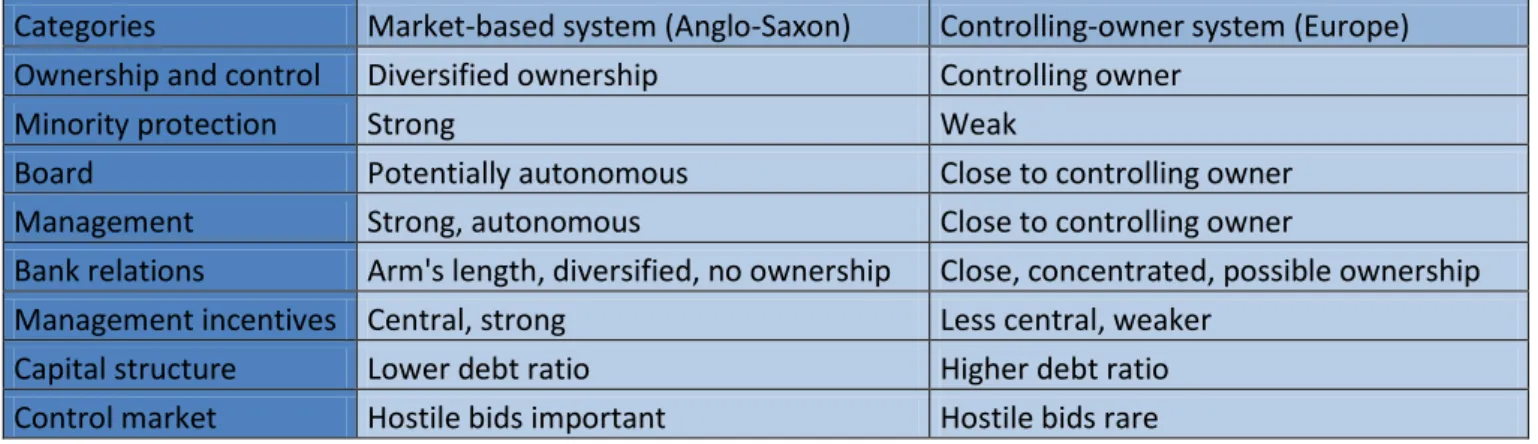

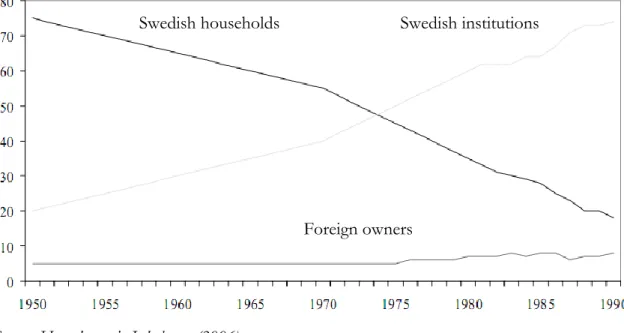

With this background it would be interesting to investigate the Swedish market for corpo-rate takeovers to see whether there is any correlation between the ownership structure and the occurrence of hostile takeovers in Sweden. The corporate control of Swedish listed firms has been very concentrated and even most listed firms are controlled by a single indi-vidual or family such as the Wallenberg sphere. Moreover we intend to look into how a po-tential change of the ownership structure would impact the market for hostile takeovers. The development with a more internationalized world and an increasing financial power of institutional investors will most likely lower the control of private owners. This will in turn lead to two possible outcomes. Either to sell the entire firm to a potential foreign investor or voluntarily reduce the inequality between their voting rights and the minority sharehold-ers (Henrekson & Jakobsson, 2006).

This thesis is produced to investigate the Swedish ownership and control model that might be in transition from a situation where a few private investors had a huge influence with controlling votes to be more focused on minority protection and to enable foreign inves-tors to invest on the Swedish stock market to a greater extent. We intend to explore whether the Swedish model which according to the theory leads to few hostile takeovers is consistent with reality.

1.2.1 Research question

In what way does the ownership structure in Swedish listed companies impact on the occurrence of hostile takeovers and how is it related to the corporate gover-nance issues facing Sweden?

1.2.2 Sub- questions

What determines the hostile bids in Sweden to be successful or not? What are the underlying reasons for the hostile bid frequency in Sweden?

What would the incentives be to change the Swedish corporate governance model and increase the number of hostile takeovers in Sweden?

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to examine how the ownership structure in Swedish listed companies impacts on the occurrence of hostile takeovers and what implications a poten-tial change in the corporate governance structure would have on it. Moreover we intend to map Sweden internationally to give a broad picture of the research area.

1.4 Outline

2. Methodology

• In this section we present the choice of subject for the thesis and explain the use of our research method. Further on, we describe the data being gathered and how it will lead us to fulfill our purpose in regards of validity and reliability.

3. Theoretical framework

• The Theoretical framework will start to entail the takeover theories and its activities, as well as the legal aspects related to the area. Thereafter, emphasize will be put on control enhancing mechanisms and other corporate governance related issues in general as well as for Sweden in specific.

4. Empirical

findings

• This section will present the variables we have used in relation to the actual outcome of hostile bids taking place in Sweden. The authors will also present how Sweden is located internationally with a focus on hostile bids taking place.

5. Analysis

• In the Analysis the authors will discuss and analyze the empirical findings in relation to the theoretical framework. Similarities and deviations in that regard will be considered

.

6. Conclusions

• The concluding section will emphasize the most important aspects of the analysis to answer the research questions in order to fulfill our purpose.

2 Methodology

In this section we present the choice of subject for the thesis and explain the use of our research method. Fur-ther on, we describe the data being gaFur-thered and how it will lead us to fulfill our purpose in regards of va-lidity and reliability.

2.1 Choice of subject

Before starting with our thesis we knew that we wanted to contribute with something in the area of mergers and acquisitions. By having a Swedish focus we realized through pre-vious research that hostile takeovers appear relatively seldom. Earlier research suggested that corporate governance issues in Sweden bears an impact on the hostile takeover mar-ket, although these derivations are in fact quite unexplored. With this in mind we decided to look at this problem more in depth.

When the idea was settled we began our literature research which was quite demanding since most of the research is based on the financial markets in the US. Because of the do-minant position the US economy and US firms have in the world economy the so called Anglo-Saxon ownership model has come to dominate the academic finance literature and analysis of ownership and corporate governance. However we have covered most of the research within this research area by focusing on preceding theses, published academic ar-ticles, published reports, printed books and underframes for national legislation in our at-tempt to cover the relevant aspects of the hostile takeover procedures, ownership struc-tures and control.

2.2 Quantitative method

Since we wanted to examine how the corporate structure may impact the occurrences of hostile takeovers in Sweden we found it most relevant to make use of a quantitative me-thod. The preference towards quantitative data stems from the fact that we examined Swe-den on such a broad basis which lead the way for a method that concluded this spectrum. By using a qualitative method where a deeper understanding of specific aspects could be highlighted would have been of certain interest but not to a degree that would suffice our examination.

When having a quantitative method the examination is based upon the relation between different data sets, which are implemented through scientific techniques that can establish quantifiable results. The quantitative method further aims to achieve generalizable results for the research at hand. In contrast to this is the qualitative method which aims to take into consideration how people perceive their surrounding, and their scientific gain can rather be viewed as an apprehension than a statistical analysis (Bell, 2000/2000).

It would have been of interest to do a qualitative study with case studies on few hostile takeovers to interview managers about certain bid strategies and motives for acquisitions. Although, since most of this kind of information is confidential it would have been hard to go through with. Also we believed that we could get more out of the problem of this re-search area by doing a quantitative study since we wanted to be able to draw statistical con-clusions and cover the phenomenon on a broader basis to highlight Sweden in comparison to other countries.

Even though we concluded at an early stage that we made use of a quantitative method the research area itself did not limit us to include a qualitative method in combination to the

quantitative one already chosen. However, due to the lack of time and effort that needed to be put into the paper whereas a combination would be existent was something that had to be taken into account. It is further worth mentioning here that our thesis did not aim to explore different views on what the Swedish economy is experiencing but rather to estab-lish a sound statement and the implications thereof, which in that concern did not lead the way for a combination of the two methods. We believed that more time and effort can be put into the exploration and development of the quantitative method that further lead us to the analysis and the result on a more objective basis.

2.3 Secondary data

When compiling information for a research one can make use of primary data, secondary data or both. Primary data is information that the researcher collect by himself/herself dur-ing the project itself, for example through interviews or surveys. Primary data can further fall into the category of official statistics and parliamentary documents (Ejvegård, 2009). Secondary data on the other hand is information that is an interpretation of the primary source (Bell, 2000/2000) such as scientific articles and doctoral theses (Ejvegård, 2009). We have made use of mainly secondary data sources. This information has been used to the ex-tent where it covered our domain of our examination in the sense of corporate governance, corporate takeovers and other thesis related information.

2.4 The abductive and deductive approach

According to Thietart, Charreire & Durieux (2001), there are two steps that need to be identified and taken into consideration when doing a research paper. The first step is ex-ploration and can be divided into either an inductive or an abductive approach. The second step is testing which follows by the use of a deductive approach.

To further explain our approach for this thesis we are going to distinguish and argument for the ways in which we conducted our analysis. Induction „usually means to assert the truth of a general proposition by considering particular cases that support it‟(Thietart et al., 2001, p. 53). Implying that what is true in some cases is attributable to other cases as well where the same characteristics are being represented. The logic of induction can be simpli-fied to an example regarding black ravens. Hence, if all the ravens observed up to a certain period in time are black then what one can conclude is that all ravens are black, this how-ever does not in any way guarantee that the next raven that will be observed is black. The problem in exploring information with the inductive approach is that whilst dealing with a large number of observations from different contexts it may be hard to extract a clear con-clusive understanding of the issue at hand. Therefore the approach of abduction comes in-to use which attempts in-to structure what has been observed and furthermore derive a mean-ing from these observations. Within the method of abduction the aim is not to derive exact universal laws but rather to introduce new theoretical conceptualizations. For the sake of simplicity a vivid example for abduction will be presented as well: If there is a couple of beans on a table and besides them lies a sack, the observer automatically wants to connect the sack to the beans given the apparent plausibility that occurs. Even it may be obvious for the observer and he/she may naturally draw the conclusion that the beans comes from the sack there are on the other hand no guarantees that these beans have originated from the sack. When using the abductive approach a researcher is enabled to make use of analo-gy in his/her explanations and furthermore make assertions. Analoanalo-gy thus refers to a simi-larity or a relationship between elements which in our case made abduction highly impor-tant since our main focus of our study was to investigate the assumed relationship between the ownership structure and hostile takeovers in Sweden (Thietart et al., 2001).

2.4.1 Doing management research

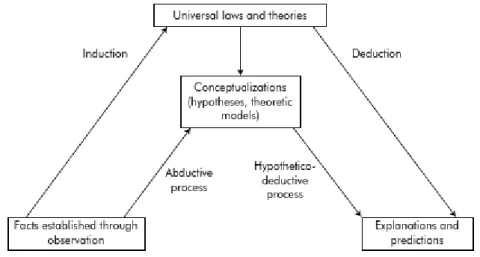

The way for which the abductive process can be tested follows with a hypothetico-deductive process. It is closely aligned and also attributable to the method of induction whereas the hypothetico-deductive approach argues that a conclusion must not be based on verification, instead one must falsify before arriving at a conclusion since a finite num-ber of observations is not sufficiently correct when deriving a scientific theory (Gill & Johnson, 2010). As we see in Figure 1, induction goes by universal laws and theories while the abductive process is more skewed towards conceptualizations in form of hypotheses and theoretical models. As we chose the abductive and hypothetico-deductive process we thought that we could get a picture of the research area closer to reality since concepts based on what you explore is better than making assumptions based on theories that might be far from a clear implementation in reality.

Figure 1: Deriving a Scientific Theory

Source: Thietart et al. (2001)

2.5 Validity and reliability

Besides the establishment of using a quantitative vs. a qualitative method or both, and what data and how the reasoning will lead to the result, a researcher always has to make sure that the data being used is both valid and reliable for the study undertaken. Regarding validity there are two main concerns one needs to highlight. First off is how the relevance is as-sessed and how precise the research results are, whilst the second aspects relates to the ex-tent for which we can generalize from the results we have obtained (Thietart et al., 2001). When measuring reliability a researcher undertakes a hypothetical reasoning in which he/she questions whether the study would yield the same result or at least as similar as possible to the current result as if the study was duplicated. Reliability concerns both the quantitative and qualitative research along the entire process even though the quantitative method was of more importance for us. The operational stages that is current within the quantitative method, and thus needs to be carefully implemented, ranges from the collec-tion, preparation and analysis of the data that are of use in the research. The better one is able to describe the research design the higher is the probability of achieving a high degree of reliability. Often research may take place over a long period of time and it is therefore an important concern to furthermore describe continuously how the research was conducted

since even the most competent scientist or researcher may run the risk of simply forgetting phases once finished (Thietart et al., 2001).

In ensuring a high degree of reliability as possible for our thesis we made use of continuous updates in this section that covered the method. Whenever the thesis evolved to a degree that implied more coverage of our conduction regarding data collection and analysis this was added in to the text and former explanations that posed no informative value were ei-ther revised or erased.

2.6 Objectivity

Closely aligned to reliability and validity there is the aspect of objectivity. For any research-er compiling a study this aspect comes into cresearch-ertain importance since it is a responsibility to strive for objectivity. It is hard sometimes to detect ones‟ own prejudices and preconcep-tions when authoring a text and it is also very probable that the source itself is exposed to subjectivity. The problem that arises is that one often has a mindset of what the facts al-ready show and what the results may yield in return why it is important to be self-critical upon the origin of a source and be critical to what the source actually tells us. By making a distinction within a sentence that what is being said is not truly objective and comes from the authors‟ point of view this approach to some extent fills the gap of the objectivity problem that occurs since future readers can choose to avoid an explicit part of the text if they wish so. In our thesis, we were aware of this and made this explicit distinction of what has been said by stating that opinions or interpretations stemmed from our belief if that was the case. We furthermore tried to focus on a language that was as neutral as possible and to that extent also minimized the use of emotionally charged terms that follows the ob-jectivity responsibility that is existent for terminologies in research papers. A last point on this matter was to have a section in the paper that handled a more thorough subjective rea-soning. We believed this as an important aspect to highlight the subjective part without confronting subjective views with objective facts. This section is called „Reflections‟ and is found in the latter part of this thesis (Ejvegård, 2009).

2.7 Empirical data gathering

The empirical data on hostile takeovers proved to be very hard to obtain. While Thomson Database offer such information we were not granted access to it, instead we settled with secondary data in a master thesis from Stockholm School of Economics being dated 2009, that made use of this database (see Appendix 1 for a further explanation). To complement this data set including hostile takeover bids at the Stockholm stock exchange between 2008 we collected data from Ägarna och Makten i Sveriges Börsföretag for the years 1995-2008, as well as from annual reports where information was missing.

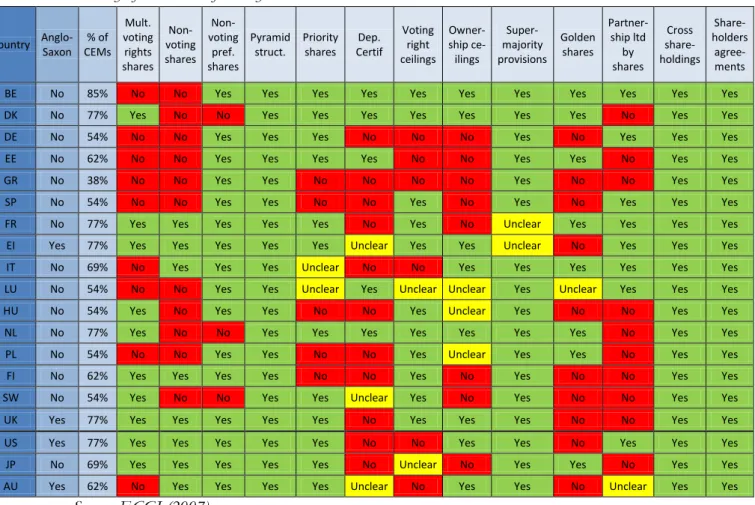

Parallel to our attempted gathering of database data we found more secondary data besides the master thesis just mentioned. For the international comparison we wanted to conduct we found data for hostile takeover bid frequency, control enhancing mechanisms, concen-trated ownership structures in posted academic articles and a doctoral dissertation. In re-gards of control enhancing mechanisms the most recent study is ECGI (2007) which is fur-ther examined in the empirical section.

In terms of how relevant the data was, we believed that the relevance was being assessed to a high degree, since it has been connected to the purpose of the thesis. To start with the ownership structure in relation to the occurrence of hostile takeovers has been summarized

in Table 5 in the empirical section for Sweden and in Table 10 and 11 for the international comparison.

Regarding how precise the empirical results were it can be questioned whether the confi-dence level was strong enough (see Table 6). Furthermore the international comparison proved to be representative population wide but the correlation was relatively weak. Since the data sometimes were gathered from different time periods, the aspect of how strong conclusions we were able to derive may clash with how generalizable the results were. This was aligned to the lack of data access but the intervals themselves were in fact intervened in each other. The actual empirical research was however adapted as to fit this divergence. The aspect of reliability was ensured to a strong degree too, as with the relevance. The data we used were cross-checked with annual reports, and we also looked into other scientific articles that had been examining the subject.

3 Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework will start to entail the takeover theories and its activities, as well as the legal as-pects related to the area. Thereafter, emphasize will be put on control enhancing mechanisms and other cor-porate governance related issues in general as well as for Sweden in specific.

3.1 Takeovers, not mergers

A takeover is, as the name implies, when one company is taking over another company. The term is used analogically to acquisitions whereas a firm or a company is acquiring an-other company, hence Firm A is taking over Firm B thus gaining control of firm B. To as-sure that one is controlling the other company it may be necessary to claim a majority of the voting rights (Sudarsanam, 2003) (Gaughan, 2007). However, in the following chapters we will see that this does not have to be the case in practice. The initial process of acquiring another firm starts with the valuation of the target firm and once this valuation is finished the bid is presented to the target firm (Sudarsanam, 2003). This initial bid is often referred to as a tender offer (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2010). In a takeover situa-tion the acquiring firm is much larger than the firm being acquired. There are some cases however when the acquiring firm is smaller than the target firm and this situation is further referred to as a reverse takeover (Sudarsanam, 2003).

Often one hears the term Mergers & Acquisitions and often situations are simply referred to this broad spectrum. Our study will not deal with the merging of companies, although the reader may want to acknowledge the differences thereof. Hence, what differentiates a merger from an acquisition is when two companies decide to unify and form one single company where none of the parties owns the other party (Sudarsanam, 2003) (Gaughan, 2007). Of course the deals will always differ from situation to situation but the most ex-plicit distinction that can be derived is that there is no party owning the other. And this goes to the complete opposite of what is attributable for an acquisition where one firm makes an offer to buy the other firm (Sudarsanam, 2003). Worth noting though is that his-tory and trends in this matter, when they are composed, seldom are given this distinction. The trends and history in the sections below should be viewed with an overall perspective of the market, thus incorporating mergers and acquisitions. Following our study further on, the reader is acknowledged when our main focus is being accounted for.

3.2 Friendly vs. hostile takeovers

There are generally two categories in which all takeovers may fall under. The first part will deal with friendly takeovers whereas the next section focuses on hostile takeovers. Even though our study focuses solely on hostile takeovers a further distinction may be necessary to highlight the characteristics of the latter. The distinction that is made whether the takeo-ver is friendly or hostile is derived from the intention to acquire the target firm as well as how the bid is presented.

Friendly takeovers are thus most often classified as this given the motives and ambitions from the acquiring firm. The motives for a friendly acquisition are those based on synergis-tic gains between the acquiring firms and the target firms. What opens up for these syner-gistic gains are, generally speaking, everything that may improve the combined business. Ranging from the combination of R&D inputs for the firms, their combined network, off-setting of profits due to tax regulations or as simple as increased market powers are factors that can drive one firm to acquire another. It is important here to bear in mind that friendly takeovers look at the synergistic gains in an acquisition. Since the takeover tries to see a

synergistic increase in efficiency these bids tends to be presented to the boards of the tar-geting firms whereas a compromise for the deal can be made. Target firms that are subject to friendly takeovers are to a higher degree categorized of either having a founder of the firm running the company or that this person is a member of the founding family than to the extent of what can be discerned for hostile takeovers. This latter aspect is to a strong degree attributable to fortune 500 companies (Morck et al., 1988).

Hostile takeovers on the other hand emphasize more on the efficiency increase that can be made solely in the target firm. A hostile takeover bid may further be presented to the shareholders only without having the board accepting the bid or even having the possibility to consult or compromise regarding the details of the bid with the acquiring firm. Hostile takeovers are often regarded as disciplinary takeovers to the extent that managers in an ac-quiring firm sees the opportunity of buying a firm under its intrinsic value and thereby in-crease the efficiency in the target firm. By replacing managers and strategies in target firms with one‟s own knowledge and expertise this type of takeover often finds itself as hostile due to the obvious reluctance arising from the board and managers of the target firm (Morck et al., 1988). Whether a hostile takeover bid on the other hand may lead to syner-gistic gains for the acquiring firm and the target firm will not be a focus of examination but, in our belief, this effect would be hard to establish given the conditions for a hostile takeover bid.

3.3 Motives for acquisition

Even though we have listed some arguments above for why firms may engage in tions when they are seeking synergistic gains, we here introduce the motives for the acquisi-tions that were evident in the US market from the 1890s and onwards. The actual takeover activity this aligns to will be presented in the next section.

In line with the different motives a firm has, there are always external changes in the envi-ronment it operates in. Technological changes have played a part in this whereas firms have capitalized on the resources and capabilities they have acquired through mergers and acqui-sitions. Besides the economic perspective that will play a part for us, the act of acquisitions can as well be explained from a managerial view which in line with a human perspective and an organizational perspective often can reveal the barriers for a successful outcome of an acquisition that is categorized by culture clashes and the quality of the acquisition deci-sion (Sudarsanam, 2003; Frankel, 2005).

As mentioned however the focus will be from the economic perspective which more tho-roughly gives us technical input into why firms behave as they do when faced with a chang-ing external environment. Under the economic perspective firms engage in acquisitions and mergers due to the favourable costs and market power they excel whilst given this engage-ment. To start off with we think it is important to highlight the criteria for the firm that act as a model under this perspective. The firm is firstly regarded as a homogenous decision-making unit where the aim is to maximize the firm value in the long run. This is done by achieving a competitive advantage over the firm‟s competitors, if this already is achieved then the focus lies on sustaining the advantage. How the firm has to act to bring a competi-tive advantage is furthermore dependant by the structure of the market for which it oper-ates in, either in a monopolistic, oligopolistic or a competitive setting. In a competitive set-ting a competitive advantage can only be achieved by being a producer of a product or ser-vice with the least costs implied. For a monopolistic market the firm can achieve their ad-vantage by avoiding direct rivalry with other firms and thus aiming for a degree of mono-poly in another geographical areas, for example a local market. For firms existent in an

oli-gopolistic market the focus of differentiating their product or service may be to compete on dimensions that are not price related, thus avoiding rivalry of stressing the price (Sudar-sanam, 2003; Porter, 2004).

3.3.1 Economy of scale

One of the most common ways for a firm to be efficient is the way it strives for economy of scale. This can be defined as the reduction in costs of a product by increasing the output of the production in a given period. The reduction refers to the average cost per product and is further dependant on fixed costs being involved in the production which normally are rents and administrative costs. The average cost per product is thus reduced since the fixed costs are spread out over a larger quantity. One should bear in mind though, that scale economies can not continue being efficient after it reaches the minimum efficient scale (MES). This is simply explained by the diminishing return for the extra unit added which implies that the MES is reached when the marginal cost of adding one extra unit ex-ceeds the marginal benefit. Given the marginal diminishing return the efficiency gains that can be achieved loses impact the bigger the firm gets, this is furthermore a limitation to economies of scale. The antitrust regulations and the EU Merger Regulation may also play an impeding role when the scale of the output can turn the combined firms to exhibit sub-stantial market power. Worth mentioning here is that scale economies are not exclusively existent in the production industry and may therefore occur for service companies as long as the firm itself has a fixed cost component that is independent of the volume produced (Sudarsanam, 2003) (Frankel, 2005; Jones & Sufrin, 2011).

Firms that expanded after the 1890‟s in the US, after the Sherman Act was implemented, aimed to a large extent for economies of scale. This way of reducing costs aligned with companies having the same customer base which lead the way to expand through horizon-tal mergers (Mueller, 2003).

3.3.2 Economy of scope

While economies of scale works best when the efficiency aims at producing a single prod-uct, economies of scope on the other hand comes into importance for firms having mul-tiple products which is often the case for a modern corporation. A scope economy thus ex-ists when the total cost of producing and selling several products for one firm is less than the total costs together for firms whom specialized and produced one product each. Ex-amples of costs that are subject to economy of scope are research and development and the use of a common distribution channel. Scope economies rely on capabilities and re-sources that are applicable across several products. To the extent this is applicable depends on the actual product portfolio but the mutual characteristics may range from having a technological basis, geographical markets or consumer groups. The applicability can also be the case of products with the same managerial capabilities and this latter characteristic proves often to be a motive for conglomerate diversification. With firms having a focus on economy of scope, increased revenues and profits affects the outcome as well, which indi-cates that the actual cost reduction not is the only effect of this strategy (Sudarsanam, 2003; Frankel, 2005).

After The Celler-Kefauver Amendment was passed in the 1950‟s, when a more strict law towards horizontal mergers was implemented, firms started to use the rationale of econo-mies of scope in order to expand through conglomerate mergers. It was widely used to adapt to these legislative changes and as the economy progressed, firms found themselves more prone to have a broader product line (Mueller, 2003).

3.3.3 Transaction costs

Parallel to the existence of horizontal mergers the business environment subjected the oc-currence of vertical mergers after the 1890‟s. The way in which the reduction of transaction costs for a firm played a part as a motive for acquisitions and mergers stems from the effi-ciency that can be gained internally by combining two firms in the distribution chain. Through vertical integration the steps in the production process can be eliminated. Mueller (2003) exemplifies this for the steel industry by saying that if ingots of steel are made by one firm and sold to another whom produces steel wires these ingots first have to be cooled and shipped and then reheated, which is a process that can be simplified by an inte-grated firm doing this work internally. Hence the hot steel can be drawn into wire right af-ter the production of the ingots. The bargaining that occurs between the two firms may al-so have an impact on the price since both firms wants to claim a great fraction of the prof-its generated by their aggregated input, which furthermore leads a vertical integration to-wards an elimination of the bargaining. It can therefore be stated that vertical integration economizes on transaction costs (Mueller, 2003; Sudarsanam, 2003).

3.4 Takeover activity

The section below will emphasize on the historical patterns of mergers and acquisitions that have occurred. The focus will begin with the activity in the United States, then Europe followed by Sweden.

3.4.1 Takeover activity in the US

As mentioned in the background a lot of what is going on in the United States generally replicates itself worldwide, which is why the takeover activities stemming from the US plays a big role here. Historically in the US there has been so called waves in the market that has been connected to takeover activity. The 1890s, 1920s, 1960s, 1980s and the start of the 21st century all faced these waves of takeover activity and a feature of these were that

the following wave always included more takeovers than the preceding one. In the US market one could see that the amount of takeovers that took place was to a strong degree related to the overall performance of the stock market. As an example, during the Great Crash on Wall Street in 1929 the effect on acquisitions resulted in a significant decline (Mueller, 2003; Gaughan, 2007).

The waves that occurred during the decades mentioned above are furthermore aligned with changes that occurred within national law. In 1890s, which had the first wave, companies acquired and even merged with other companies to create monopolies. The law that was passed on was called the Sherman Act and this law was mainly aimed at legislate the crea-tion of cartels that had occurred before this time. With the intencrea-tion of merging with al-ready established members instead of building a cartel the Sherman Act gave in that sense a rise to the wave of this takeover activity. The approximately fifty to sixty years that fol-lowed were categorized by building monopolies and it was not until 1950 the US govern-ment realized they had to implegovern-ment a law that prohibited these activities since they dam-aged the efficiency in the economy. Worth mentioning however is the Clayton Act imple-mented 1914 although this legislation aimed mainly at taking into account acquisitions and mergers that applied to stock for stock mergers (Sudarsanam, 2003). As mentioned in the section above, on the other hand, where the stock market performance was related to the amount of takeovers, the second wave thus marked its presence in line with the Clayton Act implementation (Mueller, 2003).

Up to the 1950s, the majority of the mergers had been horizontal in its nature implying that firms had merged with others in the same industry and to a large extent even with firms that had the same customer base. The economy had also seen the existence of vertical mer-gers whereas a company acquired another company or a division in the same distribution chain. These ways to expand are still existent nowadays but until the 1950s these corporate activities were not governed in national law. The Celler-Kefauver Amendment was thus passed in order to limit vertical and horizontal mergers that could impact competition ne-gatively in the market. Closely after the implementation the firms saw the alternative of building conglomerates whereas they did not intervene with the newly incorporated law (Mueller, 2003; Gaughan, 2007). The takeover activity in line with this legislation was the third wave that the US experienced.

The fourth and fifth wave started to occur parallel in the 1970s and onwards. In 1979 the second oil crisis appeared itself very evident in the decrease of the takeover activity, and the following recession in the 80s experienced the same effects. Following the recession and its effects on takeover activity onwards, the middle of the 1980s was when the activity of these takeovers started to take place again more evidently. Parallel to this increase a lot of com-panies shifted from the focus of having gigantic corporations towards a view consisting of emphasizing on the core competencies instead. One may also put forth that this (fourth wave) was an implicit change from the earlier waves that had been a result of regulations put into place whereas the new focus stemmed from a more economic mindset implying that size wasn‟t the only way forward. More and more companies saw to the possibility of gaining competitive advantage due to their somewhat preceding erosion of core competen-cies that could be attributed to the creation of conglomerate mergers (Sudarsanam, 2003). This turnaround, categorized by divestures and acquisitions by simply “reverse” the actions undertaken in the decades before, is described as “a round trip” by Shleifer and Vishny (1991).

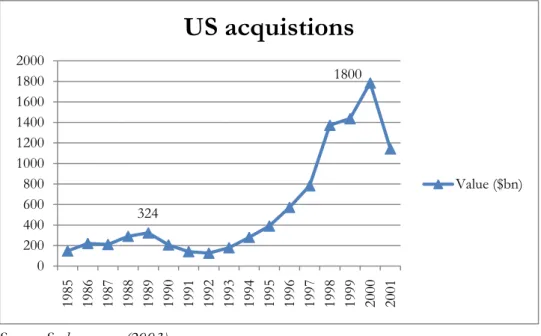

Figure 2: Takeover activity in the US during the years 1985 to 2001 as of the number of deals and the total value of these deals

A Source: Sudarsanam (2003)

The fourth wave continued until 1989 with some additional features besides those above mentioned. These features were the emergence of hostile takeover bids, a more benign

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

US acquistions

Value ($bn) 1800 324regulation towards takeovers in general plus a more intermediate use of Leveraged Buy-Outs (LBO), Management Buy-Buy-Outs (MBO) and private equity firms (Sudarsanam, 2003). The last and most significant wave, the fifth, continued with the use of divestitures and the focus on core competencies. As we see in Figure 2, the value of mergers and acquisitions‟ deals in 2000 amounted to $1.8 trillion which was an enormous increase from the last peak in 1989 with $324 billion. Besides the significant monetary increase and divestitures, the features traced back to this wave were how companies started to react upon shareholder value and how they saw a “compelling imperative” in increasing value for shareholders. Globalization also had a deep impact, not only the more borderless trading that occurred between nations but also the mobility of capital that easily could be transferred. It would be to understate that globalization did not lower the barriers to entry in new markets and pa-rallel to this existence this wave saw new markets arising from the intervention of Internet and other communication related platforms (Sudarsanam, 2003; Gaughan, 2007).

3.4.2 Takeover activity in the EU

By shifting the focus from the US market and later bring light upon the Swedish market, an introduction to what the European Union has experienced will be of explanatory power. Figure 3: Takeover activity in the EU between the years 1984 to 2002 as of number of deals and the to-tal value of these deals

A Source: Sudarsanam (2003)

The EU witnessed the same waves as the fourth and fifth ones that were evident in the US. The waves including divestitures that further became known as a global phenomenon thus affecting EU as well. According to Sudarsanam (2003), with a study of takeover activity in the EU for the years 1984 to 2002, the activity has been on average steadily increasing with a peak in 1999 of $1129 billion. The two waves that are distinguished are the ones occur-ring from 1987 to 1992 and 1995 to 2001. In the first wave the total value rose from $40 billion (1986) to $159 billion in 1992. And the second one hence increased significantly from 1992 with its peak of $1129 billion in 1999. The following years of this study however shows a decline in 2002 amounting to $224 billion (Figure 3). The EU in general follows the same pattern in history as the US counterpart regarding takeover activity (Sudarsanam, 2003). A reason to why the activity picked up in the EU also stemmed from the structural

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

EU acquistions

Value ($bn) 1129 159 224change following new legislations where large block holders started to lose their influences (Gaughan, 2007).

Table 1: Merger and Acquisition Activity and GDP in EU for the years 1991-2001

M & A and GDP in EU

Member state Share of EU M&A activity (%) Share of EU GDP (%) Ratio - M&A/GDP Luxembourg 0,5 0,2 2,5 Finland 3,9 1,6 2,4 UK 31,4 13,2 2,4 Sweden 5,3 2,8 1,9 Ireland 1,7 0,9 1,9 Netherlands 6,5 4,9 1,3 Denmark 2,6 2,1 1,2 Portugal 1,2 1,3 0,9 Belgium 2,8 3,2 0,9 Greece 1,1 1,4 0,8 Austria 2,1 2,7 0,8 France 13,5 18,1 0,7 Spain 5 7 0,7 Germany 16,3 28,2 0,6 Italy 6,2 12,6 0,5 Source: Sudarsanam (2003)Germany, France, and the UK are the most active member states when it comes to takeo-ver activity with a share of EU M&A activity of 16.3%, 13.5% and 31.4% respectively otakeo-ver the years 1991 to 2001 (Table 1). Sweden, in comparison, has only 5.3% but while putting it in relation to its share of EU GDP consisting of 2.8% they are on the other hand re-garded as somewhat overactive. Up to 2002, for which the study is ended, reflects thus that the EU has seen a huge increase in takeover activities. However what has increased more is the activity between EU and the rest of the world. This is categorized as international ac-quisitions where EU firms are either bidders or targets and from 21% in 1991 this grew to 29% in the years of 1996-99. One can compare this to the growth within EU of this activi-ty where it only increases from 13% to 15% (Sudarsanam, 2003).

Worth noting is that at the time of 2002 only 15 countries where members of the EU, while today the number is 27. Following the trend in the US and the overall global expo-sure EU has the facts revealed are still, in our belief, of imperative importance.

3.4.3 Takeover activity in Sweden

What is mentioned above is that Sweden, despite its low share of EU M&A activity, still has a relatively high takeover activity. With its share of EU GDP of 2.8% this is to be viewed as pretty impressive. Out of the 15 member states that were a part of EU in 2002, 8 states showed a lower share of EU M&A activity than their share of EU GDP (Table 1). Belgium, Greece, Spain, Italy, Austria, Portugal, Germany and France are these countries whereas the latter two still have such a high share of EU GDP already which in some

re-gards makes a comparison to Sweden, in this sense, somewhat farfetched. Sweden undoub-tedly follows the overall trends that occur within the EU although there are differences in the states‟ progress for takeover activity in regards to their own GDP (Sudarsanam, 2003). The willingness towards takeovers in Sweden has for long been a common behavior in the financial markets. Between the years 1990 and 2004 there were 358 tender offers towards listed firms at Stockholm Stock Exchange (OMX), Nordic Growth Market (NGM) and Aktietorget. Out of these offers 341 were to firms listed on OMX. 65 of the 358 tender of-fers did not lead to any acquisition. On the other hand this implies that over this fifteen year-period 293 tender offers actually lead to an acquisition of the target firm. Approx-imately this further show that per year 20 listed firm were targeted and further acquired in Sweden. Viewed another way, one can point out that 7% of the stock listed firms in Swe-den were acquired each year. Taking just OMX into account, 268 offers lead to an acquisi-tion (Sveriges Riksdag, 2006).

According to the auditing firm PwC (n.d.) the outlook for 2011 in Sweden seems to be leaning towards more domestic acquisitions. Consolidations domestically and expansions in niche markets are believed to be further dominating. The reason for why domestic acquisi-tions may increase stems from the fact that the relaacquisi-tions and similarities in the profile of the customers are more apparent domestically, hence these factors may lead to more syn-ergy effects and cost savings than acquisitions stemming cross border (PwC, n.d.).

Further reports emphasize that takeover deals will increase. A survey made by KPMG states that 8 out of 10 managers in Nordic companies expects acquisition deals in Sweden to increase. For the Norwegian, Danish and Finnish expectations only 60% of the respon-dents saw an increase in their countries. The head of M&A advising for KPMG Sweden, Christopher Fägerskiöld, is saying that venture capital firms and industrial firms will be prone for acquisitions. Regarding venture capital firms solely, some of these have the need to sell off while others need to acquire more in order to diversify their portfolio. Even though these ones are deals that emphasizes on corporate acquisitions in general they are factors affecting cases where one firm has the possibility or, at least the willingness, to get control of the other firm. Regarding acquired Nordic companies from a non-Nordic firm there was an increase from 2009 to 2010 to 158 deals, implying an increase with 48%. Ac-cording to Fägerskiöld, the acquisition of Volvo Cars made by Geely may lead the way for similar acquisitions in the future, and parallel to this there is an interest for Swedish indus-trial companies to further gain access to the Chinese market („Corporate deals set to take off in 2011: report‟, 2010).

Even though some argues that the increase will position itself domestically whereas others points out the proneness of international awareness, there will, and has been offers that never reaches its desired state. Going back to the section above, 65 offers never lead to an acquisition and the reasons for this is of course different. (1) The offer presented may be overridden by another offer on the same firm with a more lucrative price for the target firm. (2) Strong positions held by minority shareholders contradicted the offer or (3) the acquirer had insufficient funds are to mention a few things that lowers the probability of eventually acquiring the targeted firm. The offers were furthermore almost exclusively on a voluntarily basis and did not arise as a result of mandatory bids which are legislated in Swe-den (the regulatory aspects of SweSwe-den will be presented further on in this study). The ten-der offers were also overrepresented from within Sweden. The cases in which the tenten-der offer reached an acquisition for companies registered on OMX (number amounting to 268), 35 of the bidding firms were located in a member state in EU and 20 firms were from the US (Sveriges Riksdag, 2006).

The hostile takeover activity in Sweden has not been of that much focus in past studies, but there are still some one can gain further insight from. A study that has been made focuses on the years between 1995 and 2008, 216 takeover bids were tendered whereas 44 were hostile and 172 were friendly. This implies that 20% of the bids offered were classified as hostile (Bonnier & Forsvik, 2009). The first bid ever in Sweden that was classified as hostile is rooted back to 1979 when Beijerinvest made a tender offer to Företagsfinans. This offer never lead to an acquisition, instead Sweden saw the first hostile takeover to occur 1985 when Volvo tendered to buy Cardo (Clausen & Sørensen, 1998).

3.5 Swedish corporate law and EU Directive

In line with the motives for acquisitions, firms have to bear in mind the actual legal aspects in their business environment. Below the issues facing Sweden will be presented.

3.5.1 Takeover regulations

Since the Takeover Act (2006:4551), as a result of the Takeover Directive 2004/25/EC, was implemented 2007 the stock exchanges in Sweden needs to adopt takeover rules that are in compliance with the Takeover Directive. The Financial Supervisory Authority (FSA) is a state controlled body that ensures that the Takeover Directive is followed in the Swe-dish market. Besides the FSA, there is the Securities Council which is a private body that make statements and interprets the Takeover Rules. This body furthermore supervises that good practice on the Swedish securities market is undertaken by companies. The Securities Council is similar to the UK counterpart which is called the UK Panel (Sudarsanam, 2003). On October 1st 2009 the Stockholm stock exchange, had their updated regulations turning effective as of this duty of compliance. This change of takeover rules also became apparent on the NGM and First North whom as well have made an adoption of these takeover rules after the implementation. Even though the directives are put into place, Sweden could face problems in the everyday interpretation since the experience in the area is less than the UK for example. However, the directives that are put forth are quite consistent in its regards to harmonize the market. What is most consistent among the directives to create a homogen-ous playground for takeovers is the proportionality principle and shareholder decision mak-ing (Global Legal Group, 2010; Papadopoulos, 2010).

As long as the target firm is located in Sweden and traded on a Swedish regulated market the Takeover Act is applicable. The Seller needs to be absolutely sure what regulations will affect the acquisition process (Frankel, 2005). There are not special legislations for what na-tionality the bidder has, but the rulings may differ on the other hand in which sector the target firm is located in. For the airline industry and banking and finance companies that are under special supervision from the FSA, these rulings are to some extent limited to lo-cal ownership requirements. It is worth mentioning that shareholder litigations for public takeovers are very unusual in Sweden and if the Takeover rules are not in compliance the offeror could risk fines up to 100 MSEK. The FSA, in these cases, can further prohibit the offeror not to vote for the shares already held or to prohibit the standing offer towards the target firm. The non-existence of these legislations can be traced back to the attention caused by media whenever the Securities Council is criticising a takeover offer that is not in compliance with the Takeover Rules. The imposition of fines regards non-compliance with the Trading Act as well, whereas an infringement of the Market Abuse Act is a criminal of-fense (Global Legal Group, 2010; Papadopoulos, 2010).

It is not to neglect the responsibilities and rights both parties have in the process, in the meantime this has to be in rational balance of what can be harmful to the party itself when

disclosing information. The offeror wants to have as much information as possible in the process for its due diligence whilst the target board has to bear in mind to what extent the deal has processed so far (Global Legal Group, 2010). And the due diligence process itself plays a big role for the buyer to ensure that the target is sound enough to be bought for the proposed price (Frankel, 2005). If the offeror is granted price sensitive and non-public in-formation, this information has to be further disclosed to the market. It can, however be postponed if one can argue that it is too confidential and there are no risks involved in mis-leading the market. General disclosures are mutual for both parties. The target needs to in-form the market about a potential takeover if it is likely at that stage that the offer will lead to an acquisition, and the offeror has to disclose as well when preparations are made to an extent that the offer will most likely see the outcome resulting in an acquisition. If there arises a competing offer for the target firm the shareholders that already had accepted the first offer are free to withdraw their acceptance. The target board has to treat all offerors equally and shall be disclosed with the same information unless there are circumstances that would justify a dissimilar treatment on objective grounds. In the meantime, the original offeror and the competing ones can raise their bids as long it does not clashes with the leg-islations of shareholding levels discussed below (Global Legal Group, 2010).

3.5.2 Shareholder acceptance

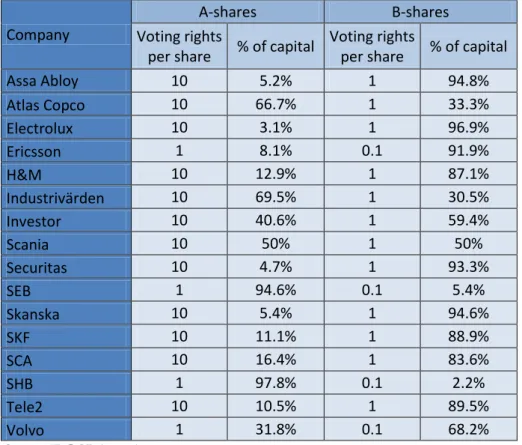

It lies in the acquiring firm‟s interest to add a premium to the market price when making the tender offer. The acquiring firm thus needs to be aware of the relevant considerations he/she must undertake. The principle of shareholder equality means that all shareholders of the same class has to be treated equally, thus identical consideration needs to be given. Holders of shares of different classes and that further differs in their economical rights aren‟t given equal consideration but the terms cannot still differ too much from each other. If we look at shareholders of different classes but also with different voting rights they will as well face terms not similar to each another but they have to fulfil certain criteria to what extent they can do so. (1) All share classes in the company has to be publicly traded, (2) the price for that share is distinguishable for the market value, and (3) the terms offered has to be approved by the Securities Council. The equal treatment may sometimes clash with how to treat target employees holding shares in their company with the potential gains an ac-quirer can make to further attract these people. The jurisdiction is here straight forward and states that any benefits to these people have to be based on their employment and not on their shareholdings in the company (Global Legal Group, 2010). The evidence put forth by ECGI (2007) shows the degree in Sweden how often these share classes differs in their economical rights.

There are cases where acquirers purchase shares before and during the offer for the acqui-sition. One reason with this is to increase their leverage in the acquisition as a whole. The acquirer is basically free to purchase the amount he/she wants to as long as the informa-tion being received from the target firm is not price sensitive, the acquirer, in those circum-stances has to wait until this information is made public. The acquirer and the target firm can also sign a so called confidentiality agreement that implies that the offeror is not al-lowed to buy any shares for a specified period. Stating that the acquirer is “basically free”, besides the preventions just mentioned, implies certain disclosure triggers and compulsory undertakings that the acquirer may face in the Swedish business environment. Disclosure triggers in Sweden regarding shifts of certain shareholding levels applies to all companies and hence not only firms subjecting a takeover. These levels are 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 50, 66.67 and 90 percent and exceeding or descending these ones the FSA and the is-suer/target has to be notified. For major shareholders such as directors or officers for

ex-ample there lies an obligation to notify the FSA regarding their holdings whenever these changes as long as they are holding 10 percent of the voting rights (Global Legal Group, 2010; Simmons & Simmons, 2004).

What is further compulsory for an acquirer in an acquisition process is the so called manda-tory bid threshold that is legislated in Sweden as a result of the Takeover Act. If someone is acquiring shares to an extent that implies a controlling position of 30 percent of the voting rights this requires that the bidder makes a public offer for the rest of the shares in the tar-get company. The acquirer has four weeks to reduce the shareholding below this threshold if he/she not wishes to make this extended acquisition. An update in this area concerns the proposal made by the Swedish Industry and Commerce Stock Exchange Communitee in October 2009 in which an additional measure would be introduced. Before the 30 percent threshold was in place (implemented 2006) Swedish companies faced a threshold of 40 percent. Following the change of this an approximate number of 40 to 50 listed companies were positioned with holdings between 30 to 40 percent thus making them unaffected of the recent implementation. The proposal states that the additional threshold should be placed at a 50 percent threshold in order to limit controlling interests like this without harming minority shareholders. An effect of the mandatory bid threshold is that companies seek to gain controlling interest above this level with the use of equity derivatives. How-ever, in most of these cases the Securities Council needs to give their view and approve since it often intrudes on good market practice(Global Legal Group, 2010; Papadopoulos, 2010).

3.5.3 The hostile aspect

As mentioned in the earlier sections, what makes an offer hostile versus friendly is how the offer itself is presented and the reactions of the target board. In Sweden there are no direct legal constraints whether you want to acquire a firm on a friendly or a hostile basis. What one has to bear in mind is that the target board plays a vital role in the takeover process. The board needs to act in the best interest of the shareholders and if they are not satisfied with the bid price the accessibility to information for the due diligence process will be very limited. In that case the target board, therefore, will not recommend the offer to the share-holders and the due diligence information will thus be based on publicly available informa-tion solely. A hostile takeover may therefore require more planning in price justificainforma-tions when presenting the hostile bid to the shareholders instead (Global Legal Group, 2010). The hostile bid also requires more advisors since target firms may resist the offer on regula-tory grounds (Gaughan, 2007).

If a target board is faced with an offer they find unreasonable, there are no legislations say-ing that this information has to be brought to the shareholders when the offer is presented. However, two weeks before the acceptance deadline of the offer the shareholders of the target firm needs to be granted this information. If the timeframe of the acceptance is very long this makes up for the target board to consider a variety of ways in how to deal with the situation, both positively and negatively. Given the case that the target board is not sat-isfied with having a bid imposed upon them, they of course still need to act in the best in-terest of the shareholders. Actions that would intrude on a successful outcome in the proc-ess needs to be approved on the general meeting with the shareholders. What the target board is allowed to do ranges from exploring other options, announce new information and forecasts or by referring to an offeror‟s bad financial condition (Global Legal Group, 2010). The target board may as well seek a white knight, which is when they seek for an-other bidder that can grant them a more favourable offer (The Guardian, 2007).