Eating and togetherness in

“long-distance families”

Eating Means We Love You

Luna Fisker

Interaction Design

Master level, Two-Year Master 15 HP

Abstract

The increased mobility of people, as they relocate for job or work opportunities, cause some families to be separated for a substantial amount of time. Since this prevents the dinner table from being the natural gathering point for families, other ways of sustaining the relationships must be considered. This thesis finds that the feeling of togetherness is an important quality of eating together, and explores how this can be transferred to a physically distant family member. By exploring ongoing connectedness and symbols of presence, a concept is proposed to aid families in long distance relationships, to feel togetherness.

1

Outline...4

1.1 Introduction ...4 1.2 Research questions: ...4 1.3 Limitations: ...5 1.4 Ethics ...52

Background/theory...5

2.1 Eating together – Commensality...5

2.2 Celebratory Technology...6

2.3 Phatic Communication ...7

2.4 Canonical examples...8

3

METHOD ...12

3.1 Research through design ...12

3.2 Ethnographic research and auto-ethnography...13

3.3 Embodied imagination (Placebo Sleeves)...13

3.4 Synthesizing ...13 3.5 Sketching...14 3.6 Prototyping ...14 3.7 Project plan...15

4

Design process ...16

4.1 Discover ...16 4.2 Define ...16 4.3 Develop...25 4.4 Deliver...305

MAIN RESULTS AND FINAL DESIGN...35

5.1 Main results ...35

5.2 The final concept: Eating Means We Love You ...37

6

EVALUATION/DISCUSSION ...37

7

CONCLUSION ...39

8

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...39

8.1 References ...39

1 Outline

1.1 Introduction

Eating together is a way of showing commitment to your family and a place to touch down and have quality time with loved ones. Although sharing a meal is one of the best ways of bonding with others (Davis, 2018), it is not always possible in a world that is constantly changing, as ideas; information and humans are moving from one physical area to another (Fuglsang, 2015). Since 1975, the number of international students worldwide has increased from 0.8 million people to 4,1 million in 2010 (

OECD (2012)

. In Danish context, 11.600 Danes on tertiary-level leave home each year to study abroad, commonly for periods of 4-6 months (DST, 2015). Globalization has not only caused students to move, but also the work force, resulting in 84.000 Danes working and living abroad, not to the mention the 109.000 foreigners working and living in Denmark (Ravn, 2019). These numbers suggest that worldwide, a huge amount of families is divided for shorter or longer amounts of time, as people move for school or job opportunities.Whilst meals and commensality are often the result of local traditions and norms, this increased mobility has changed how people eat together, sometimes completely preventing it. But if the dinner table is the family’s gathering point and eating together a symbol of commitment, what happens to families who are unable to share supper and how can the feeling of togetherness be supported instead?

This thesis project focuses on how technology can help families that are physically apart to feel togetherness. The subject will be explored in a designerly way, by exploring possible futures, starting from a situation at hand. Intending to change the situation for the better by developing and introducing some sort of product or service, i.e., the concrete outcome of the design process (Löwgren, 2007: 1). The outcome of the design process will be a prototype or a concept that intends to be a future solution to the problem, based on the design inquiries of the thesis project.

1.2 Research questions:

What are the qualities of commensality that seems relevant for designing a technology or artefact to support the relationship between family members who are unable to eat together, due to physical distance?

1.3 Limitations:

Considering the time frame, the intention with this paper is not to present a finished product, but to document the design process that leads to a concept or prototype supporting the relationship of family’s being in “long distance relationships”. The research is limited to family dinners eaten in a domestic environment: “at home”. The research will be focused on individuals who normally participate in these activities, but are currently not able to because they are working abroad or is part of an exchange program.

1.4 Ethics

In accordance with The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR 2018), data that has been collected containing personal information has been handled to the best of my abilities according to the guidelines.

2

Background/theory

2.1 Eating together – Commensality

Commensality can be understood in two ways. It can be defined as eating the same food together, as described by French sociologist Claude Fischler (Fuglsang: 2015), or it can mean solely ‘the practice of eating together’ (not necessarily the same food) as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary. In this thesis, the latter definition of commensality will be used.

The joys and benefits of commensality are many and far-reaching. It is a way for humans to distinct themselves from the primitive, by turning an animalistic instinct and bodily necessity into a civilised social arena, in which norms are superior to human needs (Fuglsang, 2015).

In Christianity, the act of receiving the Body and Blood of Christ is called ‘Communion’, meaning fellowship. The Supper (the church sacrament) is considered both a declaration of love and a sign of community with God and between Christians altogether (Andersen, 2014). Eating together is in most communities still considered a declaration of love, and the act of cooking for others is considered a gift (Fuglsang, 2015). Eating together is a way for the individual to show commitment and interest in taking part in the – also secular - community (Andersen: 2014). Eating dinner with your family, joining co-workers for lunch or inviting friends over for a seasonal feast. The meal is regarded as a place of confidentiality and has for decades been used, as the daily gathering point for the closest family (Fuglsang, 2015).

Dinner time is a great opportunity for parents to pass values and worldviews onto their children. The conversation during mealtime is an exercise in democracy and involvement in the world and with others (Andersen, 2014). It is a way of connecting with others and a way to battle loneliness (Hoff et al, 2018). Though commensality in families may seem repetitive and trivial, the dinner table has a very important place in family life, as it is a touch point between family members meeting in mutual recognition of the importance of togetherness. In the words of Johannes Andersen, from his 2014 book:

Commensality gathers and invites to even more. To tell about the day and about important thoughts. To ask about money and overdrafts. To scold and to declare an

engagement. To hear about young and old. To see children and grandparents. Commensality is an open

space, a break and an invitation to attend. Almost a declaration of love (…). A form of civilized behaviour,

which could be as fundamental as eating itself.

(Andersen, 2014: 55, my own translation).

2.2 Celebratory Technology

Most technology that deals with the relationship between humans and food, deals with meal planning and nutrients (Grimes & Harper, 2008). Andrea Grimes and Richard Harper coins the term “corrective technologies” as an umbrella term for all these technologies, that are created to change the relationship between humans and food. Areas well-explored in corrective technologies are: uncertainty, distraction, inexperience and inefficiency (Grimes & Harper, 2008). Corrective technologies, see problems in the way humans interact with food and introduce ways of changing it. Because food is vital, Grimes and Harper proposes that you should introduce corrective technologies only with extreme care and only if you are sure the behaviour should me amended (Grimes & Harper, 2008).

Celebratory Technology is another approach, coined and introduced by Grimes and Harper, in which an area is explored, and a design is created on the basis of the positive and successful aspects of human behaviour (Grimes & Harper, 2008: 2). This has two positive outcomes: first, there is a chance that completely different designs will arise from this approach, and secondly that human failure is often much more than just failure. When it comes to culinary skills, failing is a way of learning and a way of gathering experiential knowledge (Grimes & Harper, 2008). In their 2008 paper on New Directions for Food Research in HCI, they identify seven positive areas of Human Food Interaction that they consider fit to be designed for: creativity, pleasure, nostalgia, gifting, family connectedness, trend-seeking behaviours and relaxation. The end goal of designing for these areas is to augment the current

situation, by making a design that celebrates human behaviour instead of improving it or correcting it.

2.3 Phatic Communication

Figure 1 Jakobson’s Model (from Awareness Systems: Advances in Theory, Methodology and Design: Markopoulos, Mackay, & Reuter, 2009)

The term ‘phatic communication’ was coined by Bronisław Malinowski in 1949, meaning, a type of speech in which the ties of union are created by a mere change of words (Markopoulos, Mackay, & Reuter, 2009: 176). In 1981, Roman Jakobson created a model of communication, breaching the gap between two schools of thoughts in communication: process and semiotic (Markopoulos, Mackay, & Reuter, 2009). The Process model sees communication as a conduit, dealing with coding and decoding messages between sender and receiver and emphasises on the accuracy and the efficiency of the transmission (Markopoulos, Mackay, & Reuter, 2009). The efficiency means that the sender of the message has a goal with the interaction. If the interaction does not lead to the sender’s goal, the communication is seen to have failed.

The Semiotic model deals with production of meaning. It is more interested in the receiver and how the message is read, than in what the sender intends. This means that miscommunication, in the Semiotic school, is not seen as a failure of communication, but as a product of e.g. the cultural differences between sender and receiver (Markopoulos, Mackay, & Reuter, 2009). In Jakobson’s model (figure 1), the six elements of language (in bold) are paired with a function (in italics), describing how people use language. In this review, only the phatic function will be described. Phatic communication deals with the space in which communication is possible and desired, even if the message is not informative (Markopoulos, Mackay, & Reuter, 2009). Even if the phatic function does not deliver any data it is not a futile function: Even though no new information is sent, the act ensures existing

communication channels are kept open and usable. This message maintains and strengthens existing relationships (Markopoulos, Mackay, & Reuter, 2009: 176).

2.3.1 Phatic Technology

Phatic technologies are communication technologies that seeks to maintain social relationships by expressing emotions. This can be done differently, from either written or verbally to ‘unspoken’ ways (Gibbs et al, 2005). Instead of focusing on being information heavy, phatic technologies are designed to aid relationships by sustaining intimacy through ongoing connectedness (Gibbs et al, 2005). It is in the repetitiveness of the act that the relationship is maintained and the sense of connectedness is gained, and not because of the actual content (Markopoulos, Mackay, & Reuter, 2009). It is about: Seizing the opportunity to express love in mundane every day acts (Gibbs et al, 2005: 4).

2.4 Canonical examples

2.4.1 SynchroMate

The SynchroMate is designed based on a study conducted by the Interaction Design group at Melbourne University in 2003-2004. Through fieldwork they discovered that ongoing connectedness was important for people in relationships: Technology was often used for exchanging simple missives and tokens of affection, and for ‘idle chatter’ about ‘nothing in particular’ (Gibbs et al, 2005: 3) Couples would communicate with each other using messages containing very little actual informative content, but the messages would still be deemed very important, for maintaining intimacy (Gibbs et al, 2005).

The fieldwork also concluded that people in intimate relationships would sometimes e-mail, text or call each other up at the same time, as if their messages would ‘cross each other’ mid-air. This notion of having thought of each other at the same time, was regarded by the couples as a ‘special connection’.

The SynchroMate is a phatic little wearable that fits in the palm of your hand. It helps serendipitous moments, as mentioned above. It works by changing colour on the SynchroMate screen when someone composes a message for you. The colour on the screen depends on who is writing, allowing the owner of the SynchroMate to know who is drafting a note for them, and gives the wearer the opportunity to compose a message at the same time.

Figure 2 SynchroMate (from SynchroMate: A phatic technology for mediating intimacy: Gibbs, M. R., Vetere, F., Bunyan, M., & Howard, S, 2005).

2.4.2 Ritual Machines I & II

Figur 3 Drinking Together Whilst Apart and Anticipation of Time Together (from Ritual Machines I & II.: Kirk, D. S., Chatting, D., Yurman, P., & Bichard, J., 2016).

Ritual Machines I and II are material explorations of family lives and practices affected by families being a part due to working abroad (Kirk, Chatting & Bichard, 2016). The design research was conducted giving cultural probes to two families, in which one adult would be out of town for shorter or longer periods due to work. The results of the cultural probes and interviews with the families resulted in two design ideas, ‘Drinking Together Whilst Apart’ and ‘Anticipation Of Time Together’.

Drinking Together Whilst Apart is an electronic remote bottle opener

connected to a smartphone app. The app can be used to pour a glass of wine through an electronic wine dispenser ‘at home’. The two devices are connected via the internet. When a glass is inserted into the wine dispenser machine, the person with the electronic bottle opener receives a notification through the app. When this person uses the remote bottle opener to open a bottle of wine, a glass of wine is poured ‘at home’. The glass is only poured

when the remote bottle opener is being used to open a bottle, it cannot be poured by a shortcut through the app (Kirk, Chatting & Bichard, 2016).

Anticipation Of Time Together is a design that can: structure a ritual around setting a countdown timer in anticipation of a future event, probably a shared holiday or becoming reunited (Kirk, Chatting & Bichard, 2016: 2470).

A flip-dot machine and two iPhones with the designed app is connected through the internet. The flip-dot helps keep track of time whilst resembling both the message boards at airports as well as a watch by the ticking sounds of the dots flipping. In order to make a countdown for a future event, both people must stand close to each other with their iPhones. When the iPhones are next to each other a date can be plotted in by making circular movements on both screens. The system only accepts input when the two people work together, finishing a circular movement on one screen on the other. When the date has been negotiated, both people must click their screens to agree. After this a countdown will begin, flipping a dot on the flip-dot machine one at a time, depending on how near or far in the future the event is set.

2.4.3 The Good Night Lamp

Figure 4 Good Night Lamp (from http://goodnightlamp.com/)

The Good Night Lamp is another example of a phatic technology. Instead of being information heavy, it offers an ambiguous way of communicating with loved ones who lives far away. By clicking the button in the chimney of the big house (see figure4), you turn on the light in the small house. There is only this one way of turning it on, however the meaning of the light signal in the little house can hold many meanings. According to the designer’s it can mean anything from: ’now’s a good time for a chat, ‘I’m thinking of you’ or ‘call me when you get home’ (http://goodnightlamp.com/). This design differs from the three previous mentioned designs, as the interaction is one-way only. If

the person with the little lamp wishes to respond, he or she will have to do so using another technology.

2.4.4 The Skype Dining Set

Figure 5 The Skype Dining Set (from https://www.lamdazita.com/skype-dining-set) The Skype Dining Set is a design work created by Louisa Zahareas that seeks to; Create the illusion of social presence and enhance the feeling of

togetherness (https://www.lamdazita.com/skype-dining-set). The semi

circled shape of the plates combined with the positioning, makes the optical illusion that two individuals sharing dinner through Skype, are also eating from the same plate.

2.4.5 Eating with Moomin

Figur 6 Eating with Moomin (from Table for one? Restaurant offers giant stuffed animals for company: Fishwick, C. 2014).

The Moomin Café in Tokyo offers guests to eat ’with’ giant stuffed moomin figures, in an attempt to battle loneliness (Fishwick, 2014). Although it does not offer any interactive components, the stuffed moomin probably provides a feeling of co-presence.

2.4.6 Canonical examples conclusion

The canonical examples all address intimacy/togetherness. SynchroMate considers togetherness/intimacy as a “special” connection that can lead to serendipitous moments. It sees togetherness as the ongoing interaction between partners, who can quickly and secretly send messages from the palms of their hands. Drinking Whilst Apart, deals with togetherness differently. It is not the small interactions throughout the day it is prioritizing, but instead the moment when both partners have time to sit down - at the same time and despite distance - to share a glass of wine together. The Skype Dining Set also seeks to increase togetherness using an illusion of physical interaction between the two users. In this case, the shared plate is meant to serve as an extra symbol of the togetherness between the diners. By ritualising the moment in which a future event is created, Anticipation Of Time Together creates togetherness. The countdown serves as a reminder of the togetherness that will happen and has already happened. The Good Night Lamp supports togetherness by enabling ambiguous signals to be sent out or received. It is different from the other designs, as the communication is one-way, since only the person with the big house can turn on the light in the small house. This means that togetherness is found both in receiving a light, that can mean many things, but also in the simple act of just sending the light out. Maybe, without knowing if the other person is home to register the light turning on.

Togetherness at the Moomin Café differs as it is achieved by sharing dinner with a symbol for another being. It could symbolize another person to the user or even symbolize a more abstract presence. Contrary to the other examples Moomin Café is the only design that targets the perception of togetherness for one person only.

3 METHOD

3.1 Research through design

Research through design, or in short RtD, is a research approach that employs methods and processes from design practice as a legitimate method

of inquiry (Zimmerman et al, 2010:310). RtD allows for research being done from many POV’s and in opposing environments. It provides an iterative process of designing and gives the researcher opportunity to reconsider and reframe the situation throughout the entire process (Zimmerman et al, 2010).

3.2 Ethnographic research and auto-ethnography

Ethnographic research is one way of performing qualitative research. The main aim of ethnography is to provide rich, holistic insight into various cultures and sub-cultures (Muratovski, 2016: 56). By observing the questioned group in their social space, you can gain insight in people’s behaviours; why and how they do the things. Opposite of experimental research, the researcher should be strictly aware of not disturbing or distorting the rituals and practices performed by the participants (Muratovski, 2016).

Auto-ethnography is a subdivision of ethnography, in which researcher’s own thoughts and perspectives from the social interactions form the central element of the study (Muratovski, 2016: 56). This is useful since experienced

life sometimes reveals other observations than explained life. Meaning one’s own experiences can add elements which would be hard to discover using other approaches.

3.3 Embodied imagination (Placebo Sleeves)

Embodied imagination can be viewed as an extension of Cultural Probes and Technology Probes. It is a way of getting a glimpse of the world through real peoples lived lives, but also a way of using the imagination of people, to ‘dream’ up new technologies, artefacts and uses. It is a way of not only exploring functionality of these future designs, but also the expressional and emotional qualities they have for humans and their lives (Hansen & Kozel, 2007). In their 2007 paper about Embodied Imagination, Hansen and Kozel introduces Placebo Sleeves as Embodied Imagination material, and concludes that; The act of wearing the sleeves created a context allowing for participants’ improvisations within their daily lives (Hansen & Kozel, 2007:

212). Embodied imagination is based on the premise that the union of the body and technology is not necessarily a spectacular thing, but an occurrence in everyday life (Hansen & Kozel, 2007). This makes it a good candidate for exploring mundane activities in the light of technology, when researching design openings and opportunities.

3.4 Synthesizing

Synthesizing is the, often overlooked, act of compressing everything you know about a subject into a clear structure of information; synthesis indicates a push towards organization, reduction, and clarity (Kolko, 2010: 1st

paragraph). In a sense, it’s about creating clarity from the - sometimes chaotic overload of information gathered in and before the design process.

3.5 Sketching

Sketching is a great way to both investigate ideas and stimulate ideation leading to new ideas. According to Bill Buxton (2011), sketching is not for consolidating ideas. It is an activity that allows designers to quickly and cost efficiently explore current ideas, identify problems and sketch over again, leading to new ideas or refining existing ones. Because of this, it is an important aspect of the ideation.

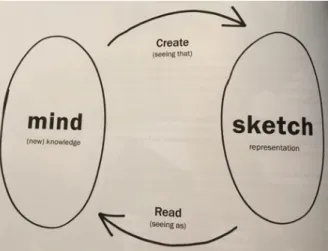

Figure 7 Relationship between sketching and exploring (from Sketching user experiences: Getting the design right and the right design: Buxton, B. 2011).

Figure 7 shows the relationship between the mind and sketch. A sketch is created from current knowledge, then interpreted leading to new knowledge. The new knowledge is then the basis of a new sketch, and this iteration process can lead to that idea, which is ripe to further exploration (Buxton, 2o11).

3.6 Prototyping

“Prototypes” are representations of a design made before the final artefact exist. They are created to inform both design process and design decisions (Buchenau, & Suri,

2000: 1).

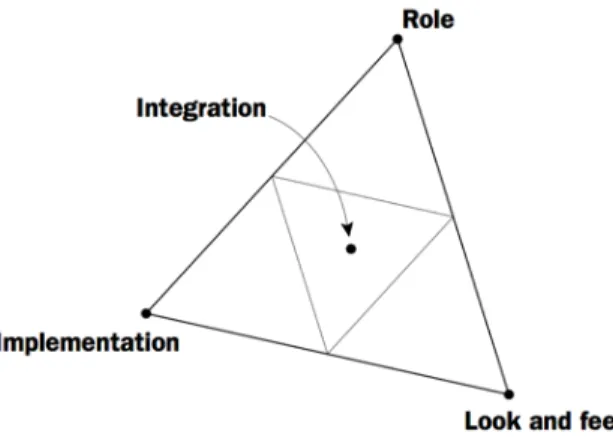

Prototypes are tools used to express and explore design ideas (Houde & Hill, 1997). Because interactive systems are very complex, it may be too costly or time-consuming to create just one prototype to deal with all aspects in an exploration. Stephanie Houde and Charles Hill (1997) suggests a model (figure 8) to help the designer identify what aspect of the interactive system the prototype explores, to “produce answers to the designers most important questions in the least amount of time (Houde & Hill, 1997: 15). To do this

they suggest building multiple prototypes that deals with different dimensions of the design. The three dimensions of the model are: Role; Look and feel; Implementation. Role-prototypes explores the function of a design in a user’s life, Look and feel-prototype explores the concrete sensory experience of using the design, Implementation-prototypes explores how the design actually works (Houde & Hill, 1997). A prototype that explores a balance between all three dimensions is called an integration-prototype.

Figure 8 Prototyping (from What Do Prototypes Prototype? Houde, S., & Hill, C. 1997).

3.7 Project plan

Figur 9 Project plan

This project has followed the structure of a double diamonds four stages: Discover, Define, Develop and Deliver. Sketching was done in all the four stages as a part of the ideation and exploration.

Project formation/Weeks 1-2:

Desktop research: commensality, celebratory technology 10/4 Fieldwork: eating with friends

Exploration/week 3:

17/4 Field study: video-call family dinner Studying canonical design examples Conceptual discovery/Weeks 4-5: 25/4 Supervision

30/4 “In what direction is the common meal going?” Lecture 1/5 Interview: Commensality and distance to loved one 2/5 Handing out Placebo Sleeves

Analysis of long distance apps Desktop research: phatic technology

Synthesis and detailed design/Weeks 6-8: 8/5 halfway seminar. Retrieving of placebo sleeves Synthesis and analysis

12/5 Workshop: sketching the design 15/5 Supervision

17/5 1 user test – Look and feel 19/5 user test – Role

Thesis completion/Week 9

4 Design process

4.1 Discover

In the first phase, Discover, desktop research was conducted to gain a deeper understanding on the subject of commensality and effects of eating together and alone. The desktop research consisted of both sociology textbooks, mainstream articles and the design approach ‘celebratory technology’. Very preliminary ethnographic fieldwork was conducted by observing a dinner-party. After the dinner, a semi-structured interview was made with the host. Canonical design examples dealing with distance, togetherness, commensality and presence was reviewed and discussed in order to find out how these subjects has previous been approached.

4.1.1 What is commensality?

Method: Ethnographic field study + semi-structured interview

To get a sense of commensality, field study was done by having dinner at a friend’s place, followed up by an interview the host subsequently. Although interesting insights about the performativity of cooking and hosting a dinner was gained, the fieldwork was not very fruitful, mostly due to the very early state of the project.

4.2 Define

In the second phase, Define, it was investigated how existing technology can be used in long distance commensality. Auto-ethnography fieldwork was conducted by setting up a video-call connection to a family dinner I was unable to attend physically. From this experiment two paths emerged: enhancing “skype-dinners” or investigating other kinds of communication technologies that could support togetherness. To find out which way would be the most viable for this project, more exploration was done.

A semi-structured interview was conducted with a mother, whose daughter has moved to Spain to live for six months. This was done to gain insights in the salient differences the mother experienced in her eating practices before and after the move.

An Embodied Imagination exploration was conducted by giving out four sets of Placebo Sleeves, investigating what communication people abroad would like to send out and receive. It was a way to let potential users “dream up” new technologies, as well as reflect on their current eating practices as well as their togetherness feeling with their loved ones at home.

A number of apps created to maintain long distance relationships was analysed to figure out how they deal with intimacy and presence. Afterwards these apps were mapped out together with the canonical examples to get a sense of what togetherness is and how it is dealt with.

Analysing these design steps, phatic technologies immerged as a viable opportunity for supporting togetherness, leading to desktop research on the topic.

4.2.1 Commensality: how does it feel to be a part and apart?

Figure 10 : how my family saw me (circled in red: me) 2nd picture: how I saw my family Method: Auto-ethnographic field study.

Materials: Smartphone, computer and a video call connection.

To experience how it feels to be both a part and apart from a family dinner I did auto-ethnographic research. By joining a family lunch at my aunt’s summerhouse by video-call I got to experience how it feels to eat together alone.

The experience of the video-call mediated dinner was pleasant. When interviewing my family afterwards, they expressed the same thing. Video-call was the ‘next best thing’, after being physical present. However, there were a few dubious things worth noting. Because of the physical restrictions of the placement of the phone, only a few people would be able to see me at a time, and I would only be able to see a few. This makes it an uneven event, as some people are overly-aware of being ‘watched’, and some might totally forget. Another constrain of the video-call is the timing it requires. First of all, the dinner took 1 hour and 45 minutes which means that the person sat alone is required to have set off a big amount of time, which might create more problems than it solves. When a person is a mobile worker or an exchange student, he or she might have more issues than missing their family and wanting to establish togetherness with the family ‘back home’. This means that taking up too much time around dinner time for Skype calls with the family, might prevent the person from pursuing relationships where they currently live, leading to more problems such as loneliness. There is also the possibility that different time zones make it impossible to eat at the same time, making the video-call dinner a Mugbank (videos or livestreams of people eating, that other people watch), more than an example of commensality.

At one point my grandmother waved to me during dinner. I waved back and she smiled, when she realised that I was present, not just a video on screen. She did not talk directly to me at any point, only this body to body communication. This moment felt very intimate. We were physically distant, but for a short moment it did not feel distant.

During the dinner, my presence became very much embodied in the technology. To my family, my body was the phone in which I appeared. “I’ll move you over here, Luna”, “You are bit hard to place without falling, Luna!”, “Now I have to charge you my little friend!”. In the Good Night Lamp

(figure 4), the light in the little house becomes a symbol of the presence of the person who has clicked the button in the chimney of the big house. The ease in which I was embodied in the phone, suggests that artefacts can serve as symbols for people, mediating presence and togetherness. This was also expressed in the following interview, when my grandmother explained that just knowing I ‘was there’ had made her happy.

A last important discovery, was the two different areas that has to be designed for. One area is for the person(s) ‘at home’ and the other one is for the one who is away. This can be designed for with different levels of symmetry or asymmetry as seen in for example, Drinking Together Apart, where input and outputs is very asymmetric. This has led to the question: How is communication made meaningful not only for the person away, but also for the family “at home”?

4.2.2 Commensality and long-distance

Method: Semi-structured interviewA semi-structured interview was conducted with a woman whose daughter has moved to Spain for six months to work. The aim of the interview was to explore the differences in the mothers’ way of eating before and after the move. See appendix (8.2.1) for the full interview.

The interview showed a lot of differences in the way the mother ate, before her daughter left, compared to now when she is alone. Besides some very easily noticeable differences (see table in appendix 8.2.2), some very interesting emotional differences were revealed as well. The mother was more present when she ate with her daughter, not only engaging with her, but also connecting more with the food: “It is just nicer and cosier to eat together. I was more present. Both with Alberte (daughter) and with the food. We would also talk a lot about the food we ate. Now when I eat in front of the television, I sometimes think “did I already eat my food? How did it even taste? I just consumed it”, because I’m less engaged.” They would be talking

about the food whilst eating it. Now, as mother is engaged with the television or her iPad whilst eating, she sometimes forgets to taste the food and just consumes it mindlessly. It is evident that most parents will miss their children if they move to another country, however there is a good reason why dinner time is special, the mother explained: “She had work and school, so we would not see each other that much. But dinnertime was a gathering point. I think that’s why... When I am having dinner... That’s when I notice she is gone.”

4.2.3 Placebo Sleeves

Figure 11 Notebooks, Placebo Sleeves, pens and after-dinner mints Method: Embodied imagination

Materials: Placebo Sleeves, notebooks, after-dinner mints, directions

An alteration of the Placebo Sleeves was created to explore what kind of communication and data that could be sent and received, and what kind of technology could be suitable.

Inside the Placebo Sleeves a little analogue motherboard, made of cardboard wrapped in copper thread, was inserted to serve as a metaphor of technology. The directions of the original Placebo Sleeves were altered in order to root the experience in the use situation of eating, and the receivers and senders to be loved ones (see appendix for altered version of directions 8.2.3). After-dinner mints was added to the Placebo Sleeve package, as a subtle reminder of the use situation.

The participants were between age 27-33, 1 male and 3 females. The participants were all chosen because they were away from their family, in order to either work or study. They all have different levels of knowledge and interest in technology, nostalgia and design work.

The participants were two Interaction Design students, from Columbia (Daniel) and China (Chang) studying in Malmö. Two participants are from

Jutland but has moved to Copenhagen. One to do a PhD in physics (Line) and one to study a master’s degree in Pedagogical Psychology (Maja).

4.2.3.1 Placebo Sleeves Outcome

4.2.3.1.1 Synchronised communication

Line writes about the importance of talking on the phone, facetiming and watching television synchronized, when being away from each other for a long time: “(my boyfriend) has been really bad at talking on the phone, and that is really difficult when I have been away for a long time. But now he is good at it. I would like to teach him to be good at video-calls and watch television together at a distance”. She also writes about the difficulties in timing skype dinners as the food has to be done at the same time, suggesting using the wearable as a remote control for a 3D food printer.

Daniel and Chang both write about synchronous activities such as phone calling and video calling, while eating and cooking. However, this is not always possible, as Chang points out in one of her first entries; her parents will still be asleep for the next four hours due to time differences.

4.2.3.1.2 Phatic Communication

Both Daniel, Line and Chang suggests ambiguous ways of communicating through the wearable. Daniel writes about sending colours, vibrations or “tightness” of the sleeve as a way of communicating. Chang writes “I would like to see some hints or messages from my friends or relatives...it could be a vibration or a piece of music or game”. Line reflects on whether togetherness can be achieved by instant communication, if the technology was a quantum computer, supporting quantum entanglement. Please see appendix (8.2.4) for a transcript of Line’s full explanation. In brief, the idea is two people having half of a whole each. Communication will happen by altering your own half, thus altering the state of the other person’s half who is also quantum entangled. What connects these ideas, is the suggestion of a phatic communication. Not conveying specific meanings, rather making the other person aware of their presence/existence.

4.2.3.1.3 A reminder

All participants describe the wearable, or perhaps the whole exercise, as a reminder. The wearable reminds Chang to eat and eating reminds her that she should remind her mum to walk: “I could not distinguish if at eating time I remember the wearable device or if it reminds me to eat something. Also, my mum never remembers to go out for a walk. We have a deal. I eat, she moves”.

For Maja, the reflection around her dining experience is about missing her mother’s comfort, as she cannot comfort herself; “This exercise makes me think about what my mum would say to comfort me. I do not succeed to comfort myself. Not at this meal.” Daniel and Chang write about ambiguous

messages as reminders for something: remembering to eat, to take a break, remembering there is a person in the other end who loves you. Maybe this kind of reminder of the connection between Maja and her mother, could have served as a comfort.

4.2.3.1.4 Conclusion

The outcome of the experiment was four notebooks with diary entries and suggestions on what the wearable could be used for. Three big themes immerged from analysing the notebooks: importance and problems with synchronised communication, eating situation as a place for phatic communication and the act of eating as a reminder.

Figur 12 What participants wish to send and receive

Send Receive

Reminders (remember to eat, I love you, go for a walk)

Reminders (remember to eat, take a break, I love you)

Food properties (smell, taste, etc.) What to eat/how to cook Ambiguous messages (colours,

vibrations, altered states)

Ambiguous messages (colours, vibrations, altered states)

Food orders to 3D printers Voice notes Comfort

4.2.4 Studying apps that deals with intimacy

Several apps have been created to mediate intimacy and ongoing presence between partners in long-distance relationships. In order to understand what the apps offer, the apps were explored and mapped out.

The exploration shows many overlapping common features and some novel features. The most common features are instant messaging, location sharing, photo sharing, showing local time of partner, in-app drawing, phone calls and shared calendars. Even though the apps shown in figure 13 are all developed to mediate intimacy, other popular apps created to connect people have many of the same features. The five most downloaded apps in 2018 were YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, Messenger and Facebook, with WhatsApp Messenger as the 13th most downloaded app (Bell, 2018). These apps also let you send

messages, pictures, videos and location. Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram’s services range from private to public.

Novel features: Couple has a feature that lets you “ThumbKiss”, by pressing the smarts phones screen the same place at the same time, the phones vibrate, resulting in a “kiss” between the thumbs. Loklok has a feature in which drawings and messages appear directly on the receivers’ lock-screen, creating an even more instant way of messaging. Heytell lets you record audio messages and send them directly. Dreamsdays and Mylove stands out as they do not connect partners through their apps. Instead they both keep track of time, Mylove by counting years, months, weeks and days your relationship has lasted and Dreamdays is a calendar service that lets you type in important events, like anniversaries or when you will see your distant loved one again.

4.2.5 Mapping out apps and designs

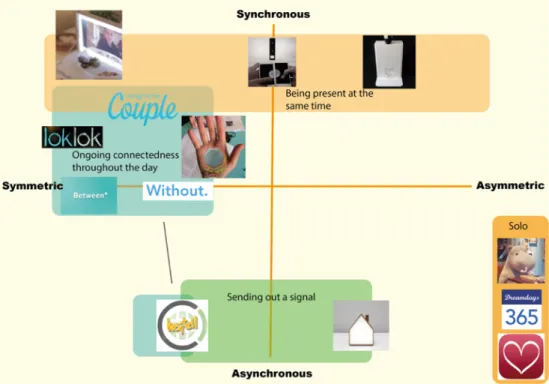

Figure 14 Canonical examples and apps

To gain a deeper understanding of the use of togetherness in present technology, the canonical design examples and the apps from figure 13 were mapped out. Synthesized, by clustering the designs on a map going from synchronous to asynchronous and symmetric to asymmetric. This was needed to see how the actual designs looked, how they worked, where they had similarities and where they had differences.

By mapping out the designs (figure 14), it was easy to discover that most designs are made to use synchronous interaction. Some with a very high focus on “doing it at the same time”: Skype Dining Set, Couples’ ThumbKiss and Drinking Whilst Apart.

Most of the designs are symmetric in both ends of the interaction, only Drinking Whilst Apart and Good Night Lamp are asymmetric.

Many of the designs (nearly all of the apps) allow for sending and receiving (photos, drawings, messages, etc.) during the day. They do not require immediate response, however as “instant messaging” implies, a certain response time is expected.

The three designs in the solo-category differs from the rest because the togetherness is not supported by being a communication between two people. Instead they deal with supporting togetherness, through the person’s experience with the design. In Dining with Moomin, the togetherness is mediated through the presence of a large Teddy Bear. In Dreamdays and

MyLove, the togetherness is mediated by seeing your relationship in numbers, either in counting down to special occasions or in quantifying your relationship into years, months, weeks and days.

What is also clear from clustering and analysing the designs is that togetherness is usually seen as being between two people. Most of the designs are created only as a one-to-one communication. If you are interested in togetherness between more than two people, you must engage with mainstream apps such as Instagram, Snapchat, Messenger and WhatsApp – as all these support group conversations. Of the canonical examples, only the Good Night Lamp is created to support togetherness between more than two people. First, the small house can be placed in a common area, so more people will receive the “light”. Secondly, more small houses can be purchased and given to other family members or friends, so they receive the light as well.

4.2.5.1 Conclusion

Not much work in supporting long-distance togetherness seems to have been done to support more than two people. Most work has been done to create synchronous technologies, despite the fact that not all people have the opportunity to be ‘on’ at the same time.

4.3 Develop

In the third phase, Develop, all insights from the process were synthesized in order to create the basis for the final design. After having digested all the gathered data an ideation workshop was held, to sketch out design ideas.

4.3.1 Synthesising

Figure 15 Colour-coded post-it’s with insights from each design stage

All information gathered from the design process was clustered into categories in order to get an overview of the relevant information (Kolko,

2010). Each design step was analysed and formulated in order to prepare next step of the design process. Please see figure 16 for main insights.

Figur 16 Main insights

4.3.2 Ideation workshop

A workshop was conducted with an interaction designer and a programmer to brainstorm on a technology that would aid a families’ feeling of togetherness when they were apart due to work or studies abroad. Based on the synthesis of earlier design steps (4.3.1), the workshop was limited to mainly address the family at home (figure 18, 1). This was decided as insights from the Placebo Sleeve experiment (4.2.3) and the analysis of apps (4.2.4) revealed that a phatic technology would be suitable for the interaction between the two situations (figure 18). Focus was therefore on how the design should function and not on the detailed contact of the interaction/communication to the person away (figure 18,2).

Figur 18 Two situations to design for, (1) at home, (2) away

From the synthesis, a range of icons had been prepared to help the creative process. To make it clear what part of the interaction was being discussed, icons were anchored around either Input or Output.

4.3.2.1 Quick sketching ideas:

By placing the icons in input and output, sketching was easily done (see figure 19). Whenever a problem immerged, other icons could replace the problematic ones, or new ones could be drawn. The sketches were quick, inexpensive, disposable, plentiful, and most importantly, In Buxton terms, they asked questions (Buxton, 2007). By putting the icon of the telephone as the input for the interaction, it was quickly realized that the phone is not a good input – at least not in a situation where several people are physically present. It can divide people instead of bringing them together. Therefore, other suggestions were tried out, ending up with the loose icon of “an artefact” on the dinner table.

Figure 19 Quick sketching, from app to artefact

Several design ideas were sketched up, surrounding the idea of an artefact placed on the dinner table “at home”. At meal times, the family members would interact with the artefact sending of a signal to the distant family member.

The distant family member could have a way of “answering”, by making the artefact at home light up, vibrate or something else. However, sketching out the interaction of this idea created new questions. Could the possibility of instant interaction be harmful to the experience? What if the family-members at home signalled the distant-family member and awaited a reasponse, but did not get one? Could this possibly make the experience worse or lonlier? A sketch was created to imagine possible outcomes (see figure 20). The family signals the distant family member (1) He/she responds The artefact responds and the family is happy. (2) The family signals The distant family member does not respond The artefact does not signal back; the family is sad.

Figure 20 Two outcomes, when awaiting response

After sketching, asking questions and disposing of ideas, a simpler idea immerged. This idea was to ritualize the act of communicating to the distant family member, and make it a part of the dinner ritual.

4.3.2.2 Design idea: Signalling the distant family member

The artefact is placed at home at the dinner table. When everybody has sat down and are ready to eat, the family members turn on the artefact. This causes something to happen on the distant family-members watch or phone. Maybe it lights up in a certain way, vibrates or sends a specific meme. This signal can mean everything from: “now we are all sat down at the dinner

Figure 21 Ritual: signalling the distant family member

Anchored in the design process, following insight is mainly addressed within this design idea:

The design addresses the ‘togetherness’ and maintenance of the family relationship, that comes from eating together.

Mealtime or the act of eating serves a reminder to strengthen the family bond/togetherness. Making it the time to connect, reflect and communicate to the distant family-member(s).

The design is suitable for asynchronous communication: as

reciprocate communication is not always possible or suitable (due to time differences, timing, other responsibilities where you are

physically required).

The presence of the missing person is embodied in the artefact. The design allows multiple users to communicate.

The artefact sends ambiguous signals, which can serve to maintain relationships, by conveying feelings like “we miss you” or “we love you”.

4.4 Deliver

In the fourth phase, Deliver, prototypes were built in order to test different aspects of the final design.

4.4.1 Prototype I – Candle light

Due to the complexity of the whole design vision (4.3.2.2) a simple prototype was created to address just one aspect of the design: embodying the presence of the distant family member in the artefact. The prototype was in Houde and Hill (1997) terms made to test the look and feel of the future artefact. The first prototype was made after a sketch from the ideation workshop (figure 22). A candle can be a natural part of dining table embellishment and in Denmark it is a sign of “hygge” (verb form of ‘cosiness’). Also, the natural movement of the flame was thought to suggest a presence.

Figure 22 Sketch from ideations workshop

The prototype was made from a plastic and cardboard packaging, originally containing a computer mouse. A smartphone playing a video of a candle light was inserted behind a cardboard with a cut-out heart-shaped WI-FI signal (figure 23). The prototype was made as a sketch, in Buxton terms, being raw and unfinished enough to “ask” for honest opinions (Buxton, 2007).

Figure 23 Prototype I

The participant was initially briefed about the context and aim of the test - finding out how to convey the feeling of presence. It was explained that when

the red button was pushed the machine would be turned on, and a connection would be made to a distant loved one.

As the participant pushed the red “button” on the artefact, the candle light video started playing. Subsequently the user was asked what he experienced. He said: I did not like that it was a candle light. It makes me think about lighting a candle for a dead person. Not something I want to think about in that situation.

4.4.1.1 Iteration I – Testing different kinds of presence

After concluding that the “hygge” in the artefact was mistaken for death a quick iteration was made. The simple built of the prototype made it possible to easily replace the candle video with other videos, audio recordings and even vibration. To see a video of the prototype, please press HERE (or see link appendix 8.2.5).

Figure 24 User test II - testing presence – changing lights

The procedure was identical to the first test. After pushing the red button something would happen in the artefact: (I) Changing colours (II) Psychedelic animation (III) Breathing (IV) Heartbeat (V) Vibrations.

The user did not like the experience of any of the audio sketches, calling them both creepy. The user responded most positive on the changing colours, as they were present without becoming a disturbance; with the changing colours, you could sense that something was happening, but it wasn’t a disturbance. The user found the vibrations incredibly disturbing and the psychedelic pattern as well: the psychedelic patterns was like having a

television turned on, which was disturbing the eye so much, that you had to look to see what was going on. Summing up the experience of the changing

colours, the user said: It made sense. It leads my thoughts to the person who isn’t present, but without dominating my eating experience.

4.4.2 Test II

Figure 25 Shaping the screen

The prototype was used for another test of the look and feel. The icon of the screen was tested by making three different cardboard cut outs (figure 26) and placing them in front of the colour-changing screen. (I) Square screen, (II) WI-FI signal screen, (III) Heart symbol. The user said that “the WI-FI logo makes it look like a router”. The square screen made the user wait for messages coming, as he thought it looked like a phone screen. The heart signal had the best response, as it suggested connection and love.

4.4.3 Test III

Figure 27 User test III (prototype placed on sideboard)

In the third test the prototype aimed to test the Role of the artefact. As the final design aims to support the communication between many (the family at home) to one, the prototype was tested in a bigger group. The participants were initially briefed about the context and the aim of the test, exploring the role of the technology in aiding the feeling of presence of a loved one.

One participant had the prototype in her hands and was asked to turn on the artefact by pressing the red button. She did so and the video began. “Everybody should be able to see it”, she said out loud and placed it on the sideboard behind the dinner table.

It seemed like the participants quickly lost interest in the artefact. It could be that the changing colours was too subtle of an effect to engage a larger group, or it could be simply because they forgot it – after all it was not present on the dinner table, but a bid hidden on the sideboard. Out of sight out of mind.

4.4.3.1 Iteration II

Figure 28 2nd iteration placed on table and close up

An iteration was made from three notebooks, cardboard cut outs of the heart logo and rubber bands. Three smartphones with the video of the changing colours were inserted behind the cardboard. This design made it possible for the artefact to be placed at the centre of the table, allowing all people around to see what was happening.

It took a little while for the participants to notice the colours were changing. When asked what they experienced, one participant said, “I wonder if the changing of colours, is the family member signalling us back?”.

Another participant said, “for a sensitive person like myself, it reminds me of love and warmth and being together even though we are not physically together”. She added that it might be useful even for feeling close to a deceased loved one, because it could serve as a good “reminder for contemplation”.

5 MAIN RESULTS AND FINAL

DESIGN

5.1 Main results

There are many qualities of commensality, it can be an expression of love, a community, a gift, a gathering point for the family, a cure for loneliness, a socialisation-process, and most importantly for this project, it is a way to

create togetherness between family members. Togetherness is a positive aspect of Human Food Interaction. By augmenting the existing practices around family dinners, the artefact can extend the feeling of togetherness to a family member who is not physically present.

Because of revelations from the video call dinner (the difficulty in many-to-one communication and problems of timing), it was decided to keep exploring other kinds of technology mediated communication. It was also at this point, the two situations that would be addressed in the design (see figure 18) were discovered; the family “at home” and the family member away. From the interview (4.2.2), and the Embodied Imagination experiment (4.2.3) it became clear that the situation of eating is a great reminder of the person/people you miss, as the dining situation is the natural gathering point for families.

Based on the Placebo Sleeve experiment (4.2.3) along with Canonical Design Examples (2.6) it was decided that phatic technology was suitable for the communication between the family at home and the distant family member, as the goal of supporting togetherness could be reached by sustaining intimacy through ongoing connectedness. This was further emphasised when analysing apps (4.3.4). Mapping out designs and apps (4.3.5) revealed the design opportunity for an asynchronous technology and a many-to-one user technology.

The ideation workshop resulted in a design vision of an artefact placed “at home” at the dinner table. Every time the family is gathered around the table to eat, they turn on the artefact resulting in a signal being sent to the family member who is “away”. This ritualizes the contact made to the family member who is away and preserves the dinner table as a touch point – even for family members who are not present.

The expression of the artefact should be something visual, that invites to engagement, but does not force it upon the users by dominating the situation (4.4.1 + 4.4.2). The visual appearance should suggest love and connection, ant not be confused with e.g. a simple internet connection or a smartphone screen.

It is important that the artefact can be watched and enjoyed from all directions, so it is suitable for being placed at the centre of the dinner table (4.4.3+.4.4.3.1). This placement allows for both engagement with the artefact and other people around the table, as well as contemplation.

5.2 The final concept: Eating Means We Love You

Figure 29 Final Concept

The final concept, Eating Means We Love You, addresses the two situations asymmetric. For the family “at home”, the relationship is supported by having an artefact that symbolises the presence of the family member. This can lead to a feeling of togetherness as well as an invitation to think and talk about the “missing” family member.

For the family member who is “away”, the relationship is supported as they receive daily reminders, from their family at home. This ongoing connectedness can lead to a feeling of togetherness despite distance. The small reminders received, can invite to think about their families at home, without causing too much disturbance in their physical reality, as no timing or large amount of time is required.

6 EVALUATION/DISCUSSION

The final outcome of the thesis is a design concept that aims to create togetherness in families, that are divided by distance due to work or studies abroad. The concept considers, that there are two situations each of which to be handled differently, in order to create the feeling of togetherness in both ends.

The experience of receiving phatic signals was not tested at all in this project, however, the results of the Embodied Imagination exploration (4.2.4) suggest that it should be well received. If I could do the project again, I would spend time testing what type of signal should be sent to the family member who is not “at home”. Phatic technology can be all sorts of messages, so it would be paramount to explore what kind of message would be preferred. Should it be a certain message/picture on the lock screen of a phone? An array of colour on a smartwatch? A meme?

It would also be relevant to test if the receiver of the signal would feel a stronger sense of togetherness, if he/she could be informed automatically about who was at the dinner table at this moment. An example of this would be: The artefacts button reads fingerprint and sends a pre-defined colour to the distant family-members. If all family members are eating at home, they all share their finger prints, sending a whole rainbow to the receiver.

Because of the very small scale of test 4.4.1.1 the result should be taken lightly. Other types of presence should be explored and on a larger population. This might reveal other preferences depending on demographics and differences in perception. However, it was a very interesting insight that the user enjoyed that “something was happening”, but that it should not be demanding/need attention constantly. I would like to explore this further - how to create an artefact so it encourages engagement but does not insist on it. One way of doing this would be to explore the area of slow technology; “A key issue in slow technology, as a design philosophy, is that we should use slowness in learning, understanding and presence to give people time to think and reflect” (Hallnäs & Redström, 2001: 203). This is pretty much what the participant is seeking when he says “It made sense. It leads my thoughts to the person who isn’t present, but without dominating my eating experience”. It is a demand for time to reflect, instead of a longing for efficiently transferring or receiving information.

The outcome of the first test of the first prototype (4.4.1) showed how important testing is. Whilst sketching up the idea at the ideation workshop, the “candle light” seemed like a great reminder of someone’s presence. However, the test showed that the user found it more of a morbid reminder,

than a reminder of togetherness. This revelation makes me question if not allowing the distant family member to respond, was a right decision. When discussing the situation at the iteration workshop, it seemed dangerous to create a situation where response was possible, in case it was not given. However, situations in which response would be given, might outweigh the negative situations with no response. There is also the possibility that the family at home would be happy when a response appeared, but not sad when it failed to appear. This response possibility should have been tested before it was ruled out.

7 CONCLUSION

This thesis project aspires to explore how technology can aid families in “long distance relationships” in feeling togetherness, when they lack the natural gathering point of eating together. The intended users of the design are family’s that would normally eat together, but are divided for a longer period due to job or study opportunities.

Research findings suggested that even though video-call dinners might be a good alternative to physical commensality, time differences, timing and the amount of time it takes, makes it a fit only in certain situations. Further exploration therefore aimed to create a design that allows asynchronous and asymmetric communication.

Finally, a design concept was proposed (5.2) - an artefact placed on the dinner table in the family home. This would be connected to a device (e.g. wearable or phone) carried by the “missing” family member. The design could aid families in “long distance relationships” by mediating presence and ongoing connectedness, thus supporting the feeling of togetherness.

The result of the thesis project is not a finished prototype, but rather a design concept ready for further exploration.

8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Daniel, Chang, Randi, Line and Maja, who took time out of their schedules to let me get a glimpse of their experience with living far from their family and loved ones. I would like to thank Maria and Simon for

brainstorming ideas and technologies with me at a critical moment. Lastly, I would like to thank Behnaz and Clint Heyer for valuable critique along the way.

8.1 References

Andersen, J. (2014). Rundt om bordet: Trængte måltider og moderne livsformer. Gjern: Hovedland.

Fuglsang, J., & Stamer, N. B. (2015). Madsociologi. Kbh.: Munksgaard. Delistraty, C. C. (2014, July 18). The Importance of Eating Together.

Retrieved April 28, 2019, from

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/07/the-importance-of-eating-together/374256/

Hoff, H., Westergaard, K., & Jakobsen, G. S. (n.d.). Madkultur18. Sådan

Laver Danskerne Mad, (2).

doi:https://madkulturen.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/madkulturen.dk/Bille der/Madindeks/Madkultur18_final.pdf

Stamer, N. B., Thorsen, G. N., & Jakobsen, G. S. (2017). Tal om mad -

Befolkningens måltidsvaner. Madindeks 2017.

doi:https://madkulturen.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/madkulturen.dk/Bille der/Madindeks/MadIndeks_2017.pdf

Davis, N. (2018, July 06). Is it true that eating alone is bad for you? Retrieved April 28, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/jul/06/is-it-true-that-eating-alone-is-bad-for-you

Brinkmann, S., & Tanggaard, L. (2015). Kvalitative metoder: En grundbog. Kbh.: Hans Reitzel.

MacMillan, A. (2017, October 25). Why Eating Alone May Be Bad for You. Retrieved April 28, 2019, from http://time.com/4995466/eating-alone-metabolic-syndrome/

Lone Koefoed Hansen & Susan Kozel (2007). Embodied imagination: a hybrid method of designing for intimacy, Digital Creativity, 18:4, 207-220 -

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14626260701743200

Zimmerman, John & Stolterman, Erik & Forlizzi, Jodi. (2010). An Analysis and Critique of Research through Design: towards a formalization of a research approach. DIS 2010 - Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems. 2010. 310-319. 10.1145/1858171.1858228. Löwgren, Jonas (2007). Interaction design, research practices and design research on the digital materials, Om designforksning. Ed. Hjelm, Sara.

Stockholm: Raster Förlag.

http://jonas.lowgren.info/Material/idResearchEssay.pdf

Kolko, Jon (2010), "Abductive Thinking and Sensemaking: The Drivers of Design Synthesis". In MIT's Design Issues: Volume 26, Number 1 Winter 2010.

Fishwick, C. (2014, May 06). Table for one? Restaurant offers giant stuffed animals for company. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/06/table-for-one-restaurant-giant-stuffed-animals-loneliness-japan

Bell, K., & Bell, K. (2018, December 04). Apple reveals the most popular iPhone apps of 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2019, from

https://mashable.com/article/apple-most-popular-iphone-apps-2018/?europe=true

Grimes, A., & Harper, R. (2008). Celebratory technology. Proceeding of the

Twenty-sixth Annual CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI 08. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357130

Gibbs, M. R., Vetere, F., Bunyan, M., & Howard, S. (2005). SynchroMate: A phatic technology for mediating intimacy ... Retrieved May 3, 2019, from

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234831640_SynchroMate_a_p hatic_technology_for_mediating_intimacy

Sarjanoja, A., Isomursu, M., & Häkkilä, J. (2013). Small Talk with Facebook. Proceedings of International Conference on Making Sense of Converging Media - AcademicMindTrek 13. doi:10.1145/2523429.2523449

Kirk, D. S., Chatting, D., Yurman, P., & Bichard, J. (2016). Ritual Machines I & II. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI 16. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858424

Markopoulos, P., Mackay, W., & Reuter, B. D. (Eds.). (2009). Awareness Systems: Advances in Theory, Methodology and Design. London: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-1-84882-477-5

Buxton, B. (2011). Sketching user experiences: Getting the design right and the right design. Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann.

Houde, S., & Hill, C. (1997). What do Prototypes Prototype? Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction, 367-381. doi:10.1016/b978-044481862-1/50082-0

Buchenau, M., & Suri, J. F. (2000). Experience prototyping. Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Interactive Systems Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques - DIS 00. doi:10.1145/347642.347802

OECD (2012), “How many students study abroad and where do they go?”,

in Education at a Glance 2012: Highlights, OECD Publishing, Paris. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1787/eag_highlights-2012-9-en

Danmarks Statistik (2016) (Ed.). (n.d.). Næsten dobbelt så mange vælger

udveksling. Retrieved May 23, 2019, from

https://www.dst.dk/da/Statistik/nyt/NytHtml?cid=21903

Ravn, L. K. (2014) (n.d.). Tusindvis af danskere arbejder i udlandet.

Retrieved May 23, 2019, from

https://www.da.dk/politik-og-analyser/eu/2014/tusindvis-af-danskere-arbejder-i-udlandet/

Hallnäs, L., & Redström, J. (2001). Slow Technology – Designing for

Reflection. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 5(3), 201-212.

doi:10.1007/pl00000019

Deschamps-Sonsino, A., & Gordon, L. (n.d.). (no title). Retrieved May 16, 2019, from http://goodnightlamp.com/

Zahareas, L. (n.d.). Skype Dining set. Retrieved May 15, 2019, from