UNBOXING CULTURAL PLANNING

- A qualitative study of finding the language of the

concept cultural planning

Faculty of Culture and Society, Urban Studies

BY212C Spring 2018

Josefina Kydönholma & Eira Bonell

Tutor: Liz Faier

Built environment,

Faculty of Culture and Society, Urban Studies

Built environment, BY212C Spring 2018

Arcitechture, Visualization & Communication

Swedish titel:

Unboxing cultural planning

- En kvalitativ studie för att hitta konceptet cultural plannings karaktäristiska språkbruk

Authors: Eira Bonell, Josefina Kydönholma

PLANNING

we need an urban

everyday life that allow us

human

being

Unboxing cultural planning

- A qualitative study of finding the language of the concept cultural planning

Authors:

Eira Bonell, Josefina Kydönholma Tutor: Liz Faier Examinator: Jesper Magnusson BY212C VT2018 Arcitechture, Visualization & Communication

Kathrine Winkelhorn for inspiration and inviting us into the world of cultural planning. Trevor Davies and KIT for letting us participate at Nordic Urban Lab in Helsinki. Last but not least thank you to all the

As citizens in an increasingly global and digitalized world, everyone feels small from time to time. Cities expand and at the same time the sense of belonging to a neighbourhood decrease. It is hard to find a way to root ourselves. While arguments occur over human nature, it is safe to assert that humans are social beings, and we have a need to interact with each other. Public spaces should fill the need of physical space were communities and neighbourhoods can meet, but trends in city planning move in different directions. We need places, paths and roads that are built for us, where there is room for interaction and encounters. We need an urban everyday life that allows us being human. Cultural planning is an approach and concept that has the potential to fill the void between city planning and citizens’ needs.

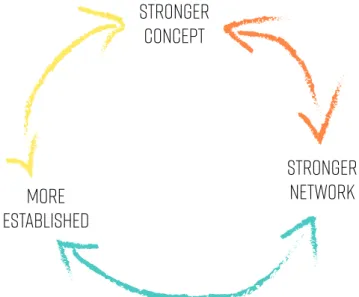

When talking about tools in the field of cultural planning, we must ask what tools exist and how do we use them? In this thesis we identify and explore a network of people and groups involved with cultural planning, as well as the different tools associated with it. Within the network, the term cultural planning is discussed as problematic. This led us to our questions: How is cultural planning conceptualized? How can cultural planning become more established and recognized? And how can the cultural planning network be strengthened?

Our goals are to unbox the concept of cultural planning by finding its language, and during our process help the network in their future work of communicating cultural planning. We call this unboxing cultural planning. The central focus of this study is the concept of cultural planning. Since the concept is complex and not yet established, we will examine cultural planning from three starting points. Using perspectives from different professions and practitioners, we explore cultural planning as a term, as an approach, and as a collection of core values. By constructing case studies and analysing them through four relevant terms, we suggest on how to widen the concept and network of cultural planning.

Som invånare i en alltmer global värld, är det kanske inte konstigt att man ibland känner sig liten. Städer växer och därmed kan känslan av att tillhöra ett grannskap lätt försvinna. En känsla av rastlöshet kan göra att det är svårt att hitta något att knyta an till. Man kan argumentera om människans natur, men att människor är sociala varelser som har ett behov av att interagera med varandra, kan nog de flesta av oss skriva under på. Publika platser bör därför fylla behovet av en plats där gemenskap kan växa, men trender inom stadsplanering verkar gå i motsatt riktning. Vi behöver platser, stigar och vägar som är ämnade för oss, där det finns utrymme för möten och samspel. Vi behöver en urban miljö som stöttar vårt vardagsliv och tillåter oss att bara vara. Cultural planning är ett tillvägagångssätt och koncept som har potentialen att sammanfoga glappet mellan stadsplanering och invånarnas behov.

I vår studie identifierar och utforskar vi ett nätverk av personer och grupper som är involverade i cultural planning. I nätverket är terminologin omdiskuterad och anses problematisk, vilket ledde oss till våra frågor: Vad är cultural planning? Hur kan cultural planning som koncept bli mer etablerat? Hur kan nätverket inom cultural planning stärkas? Våra mål är att definiera konceptet genom att hitta dess karaktäristiska språk. Detta för att hitta ett gemensamt språkbruk som nätverket kan använda. Vi kallar detta för unboxing cultural planning.

Huvudfokus i denna studie är konceptet cultural planning. Då konceptet är så pass omfattande och mångsidigt, kommer vi att undersöka det genom olika teoretiska perspektiv baserade på olika professioner, utifrån tre utgångspunkter; cultural planning som en term, som ett tillvägagångssätt och dess värdegrund. Genom att konstruera fallstudier och analysera dem genom fyra relevanta teorier, kommer vi göra ett förslag på hur konceptet och nätverket kan bli mer etablerat.

table of content

Abstract

Chapter 1; For you; an Introduction 1

Personal information 1

Problem formulation/ purpose of the question 1

Research question 3

Laying out the basics 3

Partnership with KIT 4

Theory & method 5

Limitations 5

Chapter 2; Ways of Working 7

Methodology 7

Methods 8

Processing our data 9

Chapter 3; Finding theory perspectives 11

Cultural planning as a term 11

Core values of cultural planning 12

Cultural as an approach 16

Concept findings; Ideology as a driving force 18

Chapter 4; Accessing the field of knowledge 19

ANTI festival 19

Laimikis 22

CCNC 25

Observations from Nordic Urban Lab 27

Thoughts after meetings with KIT 28

Chapter 5; Behind the words 29

Observation analysis 29

Cross-case analysis of case studies 31

Findings 36

Chapter 6; Obtaining mutual ground 37

Suggestion of content for a platform 37

Chapter 7; Final takeoff Words 43

Answering our research questions 43

Vision 44

reading instructions

In the introduction, chapter one, we will lay out the basics and the reader will here take part of essential information of the thesis’ construction. Chapter two is where we we present used methods and this thesis’ methodology is explained and justified. In chapter three we will discuss cultural planning and how it is conceptualized. Here you will find our literature review and theory section which the later chapters will lean against. Since the concept is complex, we will examine cultural planning from three starting points. Using perspectives from different professions and practitioners, we explore cultural planning as a term, as an approach, and as a collection of core values.

After the theory, in chapter four, the empirical material will be presented. The empirical material consists of; case studies, observations and note extracts from meetings. This is followed by the analysis section in chapter five, were we analyze and discuss the empirical material through four different theoretical starting points drawn from our theory section and then present our findings. Our findings will lead us in to chapter six were we present our conclusions and suggestion of how we believe the concept of cultural planning and its network can be strengthened. Finally, in chapter seven, there is a concise description of our conclusions and we finish this off with a vision of possible further research.

chapter 1

During our time at the program Architecture, Visualization & Communication, Malmö University, we have worked with questions within built environment, social sustainability and how to communicate architecture. Through our education we have developed a critical way of thinking of urban planning. Our perspective is based on the human aspect of urban life, the importance of ‘in between spaces’ and encounters of everyday life in the public realm.

During our education we have developed an understanding of identifying needs between professions in the city planning processes. We have also developed a skill in deconstructing and communicating these needs between professions and to a broader audience like communities and citizens. We have a passion and interest in the interface between the city and its citizens; how the city affects us as humans and how we, the citizens, can affect it. We believe that the concept of cultural planning has the potential to affect the urban everyday life: the smallest things can have the biggest effect.

F.Y.I

Personal info

Problem formulation & purpose of the research

We have found that cultural planning is not, yet an established approach and the knowledge of the concept needs to be spread and recognized. When attending Nordic Urban Lab (NUL) in March 2018, a conference focusing on cultural planning, we noticed a lack of a coherent body of cultural planning. With a coherent body, we mean; a collective understanding of the concept, and a functioning network that shares information and knowledge with each other on a continuing basis. The network, as we will refer it to in this thesis, consists of the people we were introduced to at the NUL conference, as well as some of the authors of the literature we have been reviewing. The reason why we see them as a group is because of their shared values and common goals. This is not an official network, rather loosely put together people with no common basis for shared knowledge of the concept.

For You; Introduction

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

Within the network there is an ongoing discussion and debate about the usage of the terminology. Some use ‘cultural planning’ whilst some prefer ‘planning culturally’. It tends to be an issue when practitioners for example present cultural planning in governing contexts. People associate culture with arts and music and tends to forget its broader definition. The word ‘cultural’ sometimes has a deterrent effect in bureaucratic contexts. Meanwhile the word ‘planning’ might have a deterrent effect on smaller groups or organisations, who does not see themselves as an influencing factor of the city. The issue with the terminology tends to limit the growth of the network.

Some of the keynote speakers were almost received and treated as rockstars during the conference. Though many of the attending spoke of reaching out and encouraging new ways and talents, at the same time they seemed to “fear” new ideas. For example, during a discussion after a workshop, an UX designer presented an idea of using a digital open source when working with cultural planning. One of the rockstars then rapidly struck back against this idea pointing out the importance of working with the physical space. This could have been an interesting discussion to develop but it was stopped in its tracks. Discussions are important, since they might lead to new ways of reaching out and working with the concept, to define it, making it flexible and dynamic.

As cities grow and people are on the move, it is even more important to create sustainable communities and cities with the citizens in focus. This is where cultural planning would have a great impact.

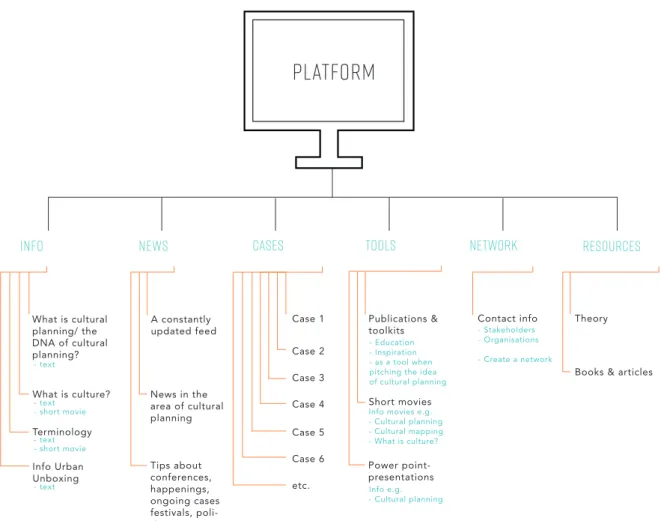

The purpose of this case study is to translate the language of cultural planning and increase the understanding of the concept. We want this to contribute to the concept being more established and recognized. We have two goals; the main goal is to have an academic discussion of the concept to create a coherent body of knowledge. The second goal is to use that body and translate it into a common language that could be used by the practitioners in their daily work. We want the common language to be inviting and easy to grasp. Our results of these two goals will be intertwined into a suggestion of content that can be applied on a digital platform. Our main idea for the digital platform is a website that will function as an open source where you can add cases and information continuously. It will work as a tool that can inspire new projects of cultural planning in a dynamic and progressive way. The content will be based on data we draw from our case studies.

By using English as the language when both writing this thesis and translating the concept, we believe it has potential to reach a broader, and international, audience. The concept of cultural planning is dynamic and responsive rather than static, which we want to be reflected in our result. O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

How is cultural planning conceptualized?

How can cultural planning become more established and recognized?

And how can the cultural planning network be strengthened?

research questions

As mentioned above, there is a lack of a collective understanding of the concept cultural planning, and there is an issue with the terminology that tends to limit the growth of the concept and network. There is also a lack of a common basis where shared knowledge, and easily graspable information for practitioners and newcomers, could be gathered. There are existing toolkits and manuals of cultural planning. However, they are targeting specific audiences, like municipalities and cities, and are static in their construction. They are based on a step-by-step idea, where one must follow them in a chronological order, and they lack real life examples. Since the usage and interpretations of cultural planning is very diverse, we believe that the common basis needs a more flexible format where examples are not forced to fit. Our research questions are;

A major player in the current context of cultural planning is Københavns Internationale Teater (KIT), who actively works with building a network through workshops, events and organizing the Nordic Urban Lab (NUL) conferences. KIT, established in 1979 in Denmark, is an independent cultural organisation that over the years has presented more than 1500 different companies, groups and artists in over 50 international workshops, seminars and festivals (Circostrada, n.d.). They want to, in an inventive and resourceful way, support a variety of performing arts which in turn will inspire and affect the city and its inhabitants (Københavns Internationale Teater, 2016, p. 302). The NUL conferences is an extended part of KIT and has been held every two years since 2014. The NUL conferences aims to spread and exchange knowledge about cultural planning and to create the basis of a network of different professions, such as; artists and planners.

Research questions

Laying out the basics

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

Through KIT and our participation at NUL 2018, we were introduced to several names in the network; such as Lia Ghilardi, one of the rockstars in the field of cultural planning. Ghilardi, through her many years, has focused on cultural planning through a method she calls DNA mapping. With DNA mapping, Ghilardi has worked with cities and municipalities in both the UK and Nordic countries, finding their core values and identities. Next to Ghilardi, another big name in the field of cultural planning is Charles Landry, who has written several books on the topic of creative city planning.

Another name, who is not a part of the NUL network, is Jan Gehl. Whilst Landry gives a more explanatory view of the upcoming of the worlds’ city planning, Gehl stresses the importance of the human scale in city planning. Both Gehl and Landry talks about the importance of encounters and places that invite us to “just be” in a non-demanding way. Even though none of them mentions or label this as cultural planning, we believe that both these views are a part of the core of cultural planning values.

As already stated; several handbooks, guides and toolkits on cultural planning has been published. Canada has come quite far in establishing cultural planning as a tool in city planning. The organisation Creative City Network of Canada (CCNC), works very actively with integrating culture in many aspects, and have different toolkits as an open source at their homepage. CCNC had representatives that held a presentation of their cultural planning toolkit and a keynote speech at the NUL conference, in Helsinki 2018. Other handbooks are for example: The cultural planning handbook: an essential Australian guide by Grogan and Mercer (1995), and Att fånga platsens själ - handbok i cultural planning (we translated this to; To capture the soul of a place - a handbook in cultural planning) by Kerstin Lundberg and Christina Hjorth (2011). These toolkits are all based on step-by-step instructions, with an estimated time duration, targeting municipalities.

These individuals, as well as theories central to cultural planning, will be discussed further in chapter three.

While this thesis reflects our ideas, research and conclusions, it is important to note that we have collaborated on some aspects with KIT. During the fall of 2017 Kathrine Winkelhorn, lecturer at Malmö University and board member of KIT, contacted us with a request to attend and work with the documentation of the cultural planning conference Nordic Urban Lab (NUL), Helsinki, March 2018. Since Winkelhorn knew of our interest and competence within built environment and visual communication, she

Partnership with KIT

O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

also asked us to develop ideas to KIT’s upcoming toolkit. Our positive response opened up the NUL conference to us as well as provided a gateway into the world of cultural planning which we could use in our thesis. It provided us with data that we used to build case studies, and equally important, it gave us an insider perspective into the network and the ways in which varied concepts and approaches are employed in cultural planning.

KIT wanted to document the conference in order to create a cultural planning toolkit. They wanted the toolkit to inform, educate and support cities, communities, artists and cultural non-governmental organizations to develop their own practice of cultural planning (Metropolis, n.d.). Our partnership with KIT has given us data for our thesis, but we have also shared our ideas on a digital platform with them and what it could include.

Theory & methods

This is a qualitative study that adopts case study methodology in order to discover and translate cultural planning into a common language that can strengthen the network. Our methods of data collection include both participant and non-participant observation. We base our research on data drawn from our attendance and observations at the NUL conference and utilize data from meetings with KIT. We have chosen to present three case studies, which we constructed from presentations at the NUL conference.

We discuss our findings through theories from different professions such as city planners, architects, theorists, critics, and activists. The civic city, civic creativity, human dimension and social capital are the four concepts we have chosen to implement when processing our case study data. The concept of cultural planning is diverse with a broad line of practitioners, users and perspectives. Therefore, the theory and literature used in this study is also from a wide range, to be representative of the concept.

Limitations

Our partnership with KIT during this thesis have given us the chance to conduct participatory research and access data from the NUL conference. However, a challenge has been that case studies and participatory observation is very time consuming. Another limitation regarding time is the language - not simply using English but also finding the language of cultural planning. Since our collaboration is with a Danish company, and the network of cultural planning is small but international, we have

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

chosen to write the thesis in English, which is challenging and there is a risk that some expressions could be lost in translation, since English is not our mother tongue.

While a partnership has been an exciting entrance into the field of cultural planning, we had to keep in mind to balance our research goals with the goals of our partners. When documenting the case studies during the conference, we used our partners’ template, which may have led us to focus on certain issues. On the other hand, it helped us with structuring the case studies. While this thesis is not explicitly participatory research, it has made clear to us the advantages and drawbacks of working with a partner organisation, were goals between researchers and organisations converge and diverge.

O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

In this section we will describe our methodology and methods, supported by theories of Robert K. Yin; who has worked with case study and qualitative research, and John W. Creswell; who writes about educational research design, mixed methods research, and qualitative methodology. We start by explaining our choice of methodology and continue describing what methods we have used in our research.

Methodology

To be able to answer how cultural planning can become more established and recognized, and how the cultural planning network can be strengthened, we needed to explore how cultural planning is conceptualized. We started by examining the concept in our theory section, viewing it from three different starting points; cultural planning as a term, an approach and its core values. To be able to study the concept’s variations we have undertaken a qualitative research using collective case study methodology. We chose a qualitative approach since we needed a detailed, in-depth understanding of the complexity of cultural planning. According to Creswell (1998, p.17) a qualitative approach is to prefer when there is a need to present your study in detail. We needed a methodology that allowed us to structure our framework during our process. Creswell (2007, pp. 37) claims that the process is the very core of a qualitative research, he describes the process as philosophical assumptions, worldviews, and studying social or human problems through a theoretical lens. The framework for the methods appears through the process; as for example case study research (Creswell, 2007, p.40). Yin (2014) states that case study methodology is used when researching the how and why. And since we want to explore how cultural planning is used and defined, we have conducted a collective case study methodology; studying more than one case. Creswell (1998, p.123) explains that case study methodology contains a wide array of data. And by applying the following methods; participant observation, direct observation and documentation analysis, a multiple source of data is given (Creswell, 1998, p.62). These are the main methods we chose because it enabled us to give a detailed description of each case. In chapter four we will present

chapter 2

W.O.W

Ways Of Working

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

each case separately and then, in chapter five, we will do a cross-case analysis based on four different terms drawn from our theory section (the civic city, the civic creativity, human dimension and social capital). We feel that the four terms chosen covers the width and depth of the case studies as well as of the concept cultural planning.

Creswell (1998, p.63) states that the more cases studied in a research will result in lack of depth, and that it is preferably no more than four cases in one research. As we want to present a broad view of cultural planning, we chose to study three different cases which enabled us to still give a fair picture of each case.

Methods

Throughout this thesis we drew on the following methods;direct observation participant observation documentation analysis visual analysis

Observations’ strength is its immediacy to cover actions in real time and has the ability to cover cases’ context (Yin, 2014, p. 106). A direct observation is observing certain types of behaviour during specific periods of time in the field while a participant observation is when you participate in the actions being studied. This is especially useful throughout fieldwork, alongside when other data is being collected in an immediate environment (Yin, 2014, pp. 113). Therefore, we found it fitting for us since our main data source has been the NUL conference, which was both place and time bound and therefore an immediate environment.

At the NUL conference we were a part of a group of students which consisted of twelve students from three universities; Helsinki, Turku and Malmö. There were in total 24 presentations and workshops which the group of students were responsible to cover under the collaboration with KIT. Out of these 24, we, the authors, oversaw four. We also attended the keynote speeches. During our time at the conference we did not have the time to go deeper in any presentations beyond our four, since it was a very tight schedule. But as participants, we were able to observe not only presentations and keynote speeches, but also see who spoke to who, have small conversations ourselves with other participants and speakers, and by that collect data; through participant observation. This to ensure that we took the opportunity of being in the present, especially between sessions. Taking part and being at the conference in first person, has provided a window for us into the field of cultural planning and an insight to how the dynamic unfolds in this network.

O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

The downside of observations could be that it is time consuming and that it may be selective (Yin, 2014, p. 106). We tried to prevent this by having a strategy based on taking notes together; one with the main responsibility, and the other one taking notes as a backup, focusing on key words and quotations. We chose to divide it like this, since we are aware that we pick up on different things. We also audio recorded every presentation, to be able to return to it later.

Another method was to draw information from a variety of documents such as; written reports of previous NUL conferences, the program and information of NUL 2018 and websites of organizations and people working in the field for example; Noema.org.uk, Charleslandy.com, Laimikis.lt, Gehlpeople.com. Yin (2014, p.107) says documents play an important role when gathering data during case study research. We have used documentation analysis as background information in our process. Beforehand the conference we wanted to prepare ourselves by having some amount of knowledge on the presentations and people attending. We are aware, as well as Yin states (2014, p.106), that there might be a risk of selectivity when for example using websites. However, the data drawn from these documents has not been directive of this thesis.

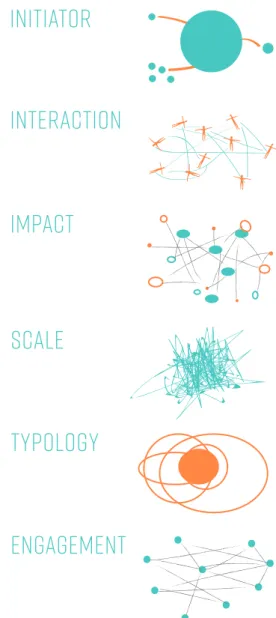

Another part of our thesis process has been mind mapping and creating visuals. This might not be an established method when reading method literature. Nonetheless, this is a method which has been introduced and used throughout our three years at the bachelor program Architecture, Visualization & Communication. We do this to complement and strengthen our text and to make some parts more easily understood. We used this especially when structuring the content for a digital platform. The visuals are also a part of our result. We have used our findings as a base for our visual work, but our visual work has worked as a tool for us to widen our own understanding on how to structure the results of the case studies.

Processing our data

As noted above, our case study data was conducted through our participation at NUL held March 22 to March 24, 2018, which occurred because of our partnership with KIT. KIT provided us with a template (figure 1) to document the workshops and case studies at the NUL conference. Even though we had our own study in mind, we had to later re-structure these notes to construct cases. We have shortened the notes following the template from approximate five pages, to around two pages. We decided to exclude specific events or descriptions of distinct installations, in order to approach our research questions. We wanted to extract the presentation’s core values rather than the specifics. We also excluded the voice of the presenter because we wanted to highlight the case itself rather than the person presenting it. However, we did include

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

some specifics which were expressive for the case. We are aware that the including and excluding is based on our personal perceptions, yet we have chosen to present the cases from a broad perspective, to prevent getting lost in the details of each case. We decided to emphasize on the foundation of each case’ ideology. Whenever we mention ideology in this thesis, we aim at the word’s meaning as a collection of social ideas and beliefs that legitimise chosen actions. We divided the cases into the following themes; main focus, the role of the city, the role of the citizens and the relationship between the city and the citizens.By having all three case studies following the same division with these themes, we believe that it would be easier to have an overview of each case but also to compare them with each other. The themes also speaks to our four chosen concepts which we use later to analyse the case studies.

Other sources of information and input is the meetings with KIT. The meetings have contributed to our process in translating and formulating the concept cultural planning. We have had three two-hour meetings, all held at KIT’s office in Copenhagen, with Winkelhorn and Davies. The focus of these meetings was to present our idea for the prototype digital platform, its content and structure.

Figure 1. Documentation template provided by KIT.

O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

Cultural planning as a term

In this section we will address our first research question; How is cultural planning conceptualized? and in the end of this chapter you will find our findings of the concept. Because of the concept’s diversity, we will look at it by using different theoretical starting points, from different professions’ perspectives on urban planning. Since there is no clear body of research on cultural planning as a concept, we have broken down the concept into three key components; as a term, its core values, and as an approach, to enhance a good overview. By doing this, we will create a greater understanding and basis of cultural planning as a concept and drive our research forward for further discussions.

It is important to know that in this thesis, when we talk about culture, we refer to the word’s anthropological definition. Culture is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, arts, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society, is the definition by the anthropologist Edward Tylor (1832-1917) and is still generally agreed as the original anthropological definition (Jenks, 2005, pp.32). Jenks also provides his own more sociological and contemporary view of culture in an urban context;

This greater definition of culture, as something so much more than arts and music, is key to understand the term cultural planning. Because cultural planning is more than just a term, it is a concept which includes ways of thinking, methods and strategies. The concept is described in many ways and depending on who or whom you are reading, or talking to, the use of terminology is different. Some prefer ‘planning culturally’ before ‘cultural planning’, while others use a totally different terminology, but still, what they all have in common is a drive towards a more humanistic way of

(Jenks, 2005, p.189)

“Analytically urban culture is the new metaphor for collective life and the new space for exploring both identity and difference”

chapter 3

F.T.P

Finding Theory Perspectives

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

(Grogan, Mercer & Engwicht, 1995, p.12)

”Culture does not simply mean the arts. It includes the arts- traditional, folk and new- and also a much wider range of human, physical, intellectual and spiritual activities, experiences, and forms. The cultural life of a community is not just about a few people going to the opera. It is about participation, celebration, identity, belonging to a community and having a sense of place.”

urban life and city planning.

Professor Franco Bianchini, Director of Culture Place & Policy Institute at Hull University, traces the origin of the term cultural planning through post-industrial societies. He claims that the first mention of the term cultural policy was in Los Angeles, in the early 80’s, as a need of an integrated link between transport policy and town planning arose (KADK, 2005, pp.13). Bianchini describes the start of using cultural planning as a response to problematic aspects cities faced during the deindustrialisation. In the early days of cultural planning, in the US, Bianchini recognizes the use of cultural planning as a band aid for cities crashed economies. Depending on the city’s conditions, there were different ways of implementing a cultural policy. For example, using culture trying to repair the economy of the declining traditional industrial cities, or using culture in a more innovative way, including media-related activities and high-tech architecture in the quest of being more dynamic. A pursuit to implement culture as a resource of status as an add-on to their already material and infrastructural wealth, could also be a driving force (KADK, 2005, pp.13). However, Bianchini (KADK, 2005, pp.13) says that the views and debate of cultural planning in its birth, may have emerged somewhat differently in other places than the US. He gives the example of Australia where cultural planning was more people-centred. There, it was connected to the debate about transforming and unifying urban areas into public spaces which promoted interaction between humans, which is closer to its contemporary meaning and usage.

In The cultural planning handbook: an essential Australian guide (1995) Grogan and Mercer state that cultural development helps people to feel that they belong in the community. This aligns with Bianchini’s rendering of the Australian approach. For Mercer and Grogan, culture and arts play an important role in both economic and social development, while cultural policy acts as a mediator between the two (Grogan, Mercer & Engwicht, 1995, p.3).

Core values of cultural planning

We are looking into the core values of cultural planning by looking at viewsfrom different perspectives and professions. In common across the professions,

O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

specified below, is their theories on people centred urban planning.

The city is like a living organism; for thousands of years the city has grown and flourished without the help of architects and city planners. It has been shaped by the landscape and the people that have lived there. This is how the theorist and architect N.J Habraken (2005, p.1X) describes the city. Also resembling the city as a living organism was the polymath Patrick Geddes (1854-1932), a pioneer of his time in looking at the city from a sociological point of view. Geddes was a polymath, who had a wide range of knowledge in many areas such as; botany, sociology, urban planning and ecology (National Library of Scotland, 2017). He represented the vision of a holistic approach, presenting the city as a living thing, explaining social and spatial problems through botanist terms as growth, blossom, decline and decay of natural evolution, maintaining that city planning also had to be about folk planning (Københavns Internationale Teater, 2016, pp.21).

Taking folk planning to its literal sense is what the Danish architect and urban design consultant Jan Gehl does. He specializes in improving the quality of urban everyday life and sees the connection between the interaction of form and life in creating good architecture (Gehl, 2010, p.XI). Gehl has developed a theory of city planning which he calls human dimension. Human dimension aims to improve aspects of the city such as; liveliness, sustainability, safety and health (Gehl, 2010, p.7). The concept of human dimension invites and give space for the citizens in the city to walk, bike, socialize and encounter public space. It is based on our primary functions and needs as human beings. This includes our five senses and our common patterns of movement. It focuses on the human perception of the city; we can see, hear and smell on certain distances and our ability of perception has a definite speed limit (Gehl, 2010, pp.34).

The human dimension contains the social field of vision (how far one can see), how we humans are able and built to move and interpret our surroundings. It is only when getting closer than seven meters we can start having a more detailed discussion. In the same way our other senses start working better as the distance to another person lessens (Gehl, 2010, pp.34). A 5 km/h architecture; with stores and details to look at when passing by, creates soft edges between buildings and the streets, giving active facades and a lively city that encourages people to dwell. With a human dimension in mind when planning both cities and activities in the cities, we allow the activity level in the city streets to flourish. In contradistinction to cities built for higher speed and cars, which only leaves empty, boring facades, with big commercial- and street signs, do not invite or attract people to stroll the streets (Gehl, 2010, pp.34). This kind of architecture does not invite interaction and spontaneous events to just happen.

An architectural theorist and critic that emphasizes the relation between

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

(Gehl, 2010, p.6)

(Landry, 2017, p. 243) “Greater focus on the needs of the people who use cities must be a key goal for the future.”

”There is a dramatic contrast between finance and social capital: with finance the more you spend the less you have; with social capital it is the reverse in that the more you encourage it the more you get.”

Since 1961, when Jane Jacobs first published her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, it has been cited numerous times, among them Gehl. Jacobs, as an activist and author, has influenced the debate of city planning. Gehl’s theory of the human dimension is, you might say, an extension of Jacobs thoughts on the importance of cross-use in a city. Jacobs pointed out that, for a centre to be used, lively and diverse, it needs to facilitate cross-uses. Differences, not duplication, enhances cross-use (Jacobs, 1993, pp. 168). Big physical barriers in an area, such as; traffic arteries, highways, big institutional groups, too large parks and shopping malls, are all a threat to cross-uses and creates island-like districts and are therefore functionally destructive (Jacobs, 1993, pp. 168). Strong neighbourhoods and districts are formed through these cross-uses, were organisation relationships, specific interests and random social encounters can carry over to the next area. This extends and enhances both individual and community networks. “These networks are a city’s irreplaceable social capital” (Jacobs, 1993, p. 180).

The author and urban critic Charles Landry (2017, pp. 243) asserts that a city’s social capital consists of the potential of the civic impulse, which he means is always present, but sometimes may be dormant. When there is public generosity, people tend to be friendlier. Landry has a “Geddesian”1 view of looking at the city and describes the social capital as the nervous system or blood stream of the city. The civic and urban commons, such as; libraries, parks and community centres, are being starved and the public space which once were places where we could meet regardless of background, life experience or if you were rich or poor, are decreasing. As Jacobs stated already in the 60’s, Landry still argues that the lack human interaction and buildings is Jeremy Till. Unlike Gehl’s detailed oriented perspective of a human scale, Till is more philosophical in his approach when talking about scale. His term the social scale involves the role of the architect. He experiments with the thought of; instead of an architect drawing with the standard scale 1:100, having one architect fill the needs of 100 citizens. Till describes the 1:100 scale as the architect’s comfort zone without having to deal with the users. By twisting the expression’s centre of gravity, the meaning changes from being something abstract and distant to an ethical responsibility for others. The social responsibility increases the minute one must interact with not only the buildings but also the citizens (Till, 2009, p.178).

1As Patrick Geddes; looking at the city

as something alive. O.M.G

B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

of neutral territory today causes a decline in mutual trust, which in the end generates a weakened social capital (Landry, 2017, p. 253). The city working as a whole could generate in a higher social value and social capital for the city’s inhabitants and communities.

Landry’s concept of the civic city is a holistic approach and includes intercultural thinking, an invigorated democracy, shared commons along with ethical purposes. However, in these nomadic times, we need to reconstruct the civic (Landry, 2017). In the Roman times the word civitas were connected to responsibilities and rights of citizenship. That means that the word ‘civic’ is conjoint to place, in contrast to the world ‘nomadic’, which means ‘wandering’ and ‘drifting’. “...to be civic means to be engaged with your city…” (Landry, 2017, p. 213). Landry (2017) claims that; by adding ‘being civic’ to ‘nomadic world’, gives the concept the civic city a more contemporary feel. The concept of the civic city is therefore based on the idea and belief that we live in a nomadic world. In the old days humans were on the move for food, animals and shelter, but today we are on the move for completely other causes. Landry (2017) states that, in our time, we are now witnessing a huge mass movement of people, goods, ideas and factories. He describes this as vast flows that makes the new norm in the world nomadic.

What Gehl, Jacobs and Landry all have in common is the idea of that our encounters, small and coincidental as can be, together create a bigger story. The challenge is how to keep the human view, when products are on constant move (Landry, 2017). We need to use city making and planning as mediation for the civic, and to create something sustainable. Landry means that a good city depends on both the civic (the relation to a community or an authority) and the civil (personal rights) being strong, and that the tension between the two is creating room for creativity. This is what Landry (2017, pp. 229) calls civic creativity, which is aiming to unlock the potentials and opportunity to serve the public realm, and advocate balance between the diversity of clashing concerns. Landry also argues that creativity is a renewable source whilst heritage is not.

(Landry, 2017, p. 231) ”The ‘civic creativity’ concept may seem incongruous, but that gives it power: holding at a tension point two qualities we rarely associated with each other, with ‘civic’ seen as worthy and ‘creativity’ as exciting and enterprising. It should be ethos for urban leadership.”

Compared to Landry’s view of the world being in motion, the urban studies theorist Richard Florida (2009) focusing on social and economic issues; recognizes the world being in motion, but has an economic theory that states that people are now tied down at one place due to homeownership. In an American context, homeownership began as a kingpin of the economy. But since the housing bubble crashed, it

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

(Københavns Internationale Teater, 2016, p. 22) ”...it can’t be a product of top-down, expert-led decision-making, but, instead, demand processes whereby the local community’s cultural attributes, habits, needs and desires find common ground for expression and co-creation.”

transformed into a constraint for creative development of cities. The society has become less nimble since the 50’s (Florida, 2009). He means that the rise of homeowners and suburbs creates less velocity and density, and that a new different geography is needed. “The places that thrive today are those with the highest velocity of ideas, the highest density of talented and creative people, the highest rate of metabolism” (Florida, 2009). He emphasises the importance of creative people for cities’ economy to thrive.

Cultural planning as an approach

Neither Gehl, Habraken, Till or Jacobs defines or defined their work ascultural planning, but they do have several aspects and similar views of the city as a notion, as cultural planning does. One who does acknowledge cultural planning as a term is Lia Ghilardi. She is the founder and director of Noema, an UK-based organization working internationally to deliver place mapping and strategic cultural planning projects (Noema, n.d.). She defines cultural planning as “a process, of getting to know a place by grasping its many cultural facets before planning can intervene” (Københavns Internationale Teater, 2016). Ghilardi has developed a strategy called DNA mapping; focusing on the people in a city. DNA mapping is a strategy to find a place’ unique cultural DNA; the distinctive characters of a certain place, which includes ways of living, social interactions and urban textures. The findings of the mapping are then used as a base for regeneration plans and community consultations (Noema, n.d.). According to Ghilardi, creating a city is not just about making decisions based on looking at a map; every specific case needs a coherent context to encourage the public towards common grounds. The local cultural habits and needs should be the base of the process when changing a city, rather than expert-led decision-making. She stresses the need of putting people and their relations with space and place first, to make holistic solutions so that cities can become more united in their vision of the future (Københavns Internationale Teater, 2016, p. 22).

Boverket is the Swedish authority for urban planning and housing. At Boverket’s homepage, one can find the manual; To capture the soul of a place - a handbook in cultural planning. The manual introduces Ghilardi’s strategy of cultural mapping which the authors describe as the foundation of how the society is lived and experienced by its inhabitants and visitors (Lundberg & Hjorth, 2011, pp. 8-10). The manual has been developed in

O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

cooperation with Swedish municipalities and county councils (SKL) and the regional federation of Södra Småland. It is intended for a regional level, targeting municipalities and counties. In the manual, cultural planning is described as a method, and advocates that the method should be used in several levels of society. For example, it could be used in a municipality, but also in a smaller scale, like a specific district of a city. It is further described by acknowledging it as a humanistic way of urban planning (Lundberg & Hjorth, 2011, p.8). The method is based on several key points with focus on mapping the cultural assets of a place, city or society to find its identity. The manual emphasises that cultural planning is not replacing politics in art and culture. Also, it is not an alternative method of city planning. Rather, it is an addition to traditional city planning. Lundberg and Hjorth (2011) claims that a good city planning should include different variables of a place’ identity and creative activities, such as; architecture, design and tourism, but also intangibles like creativity, traditions and belief in the future.

- Charles Landry, NUL, Helsinki 2018 “The city affects us, and we affect the city, it’s bloody obvious - everybody is a citymaker”

As opposed to what Lundberg and Hjorth (2011) says about cultural planning being an addition to urban planning, Landry (2008) means that planning culturally should be the very foundation of city planning. He has a rebellious and straight forward attitude towards future urban planning. Landry (2008) argues that some intelligences, especially in the western societies, remains marginalized. Even though we live in an age of creativity, these intelligences are not being promoted. The contemporary communication and intelligences already plays its role, and we need to make more active use of them in urban planning. For every matter there are appropriate tools, whereas other tools tend to limit the process and its opportunities (Landry, 2008, pp. 62-63). In line with Landry’s view of creative intelligence is Bianchini (Københavns Internationale Teater, 2016, p.37) who emphasises the importance of learning from artistic processes and cultural production, for cities to find their suppressed and possible identities. He states that artistic processes tend to be critically aware of history and the distinctiveness of the local climate.

Parallel with Lundberg and Hjorth (2011) and Ghilardi’s use of cultural planning as a strategy for looking at communities and cities needs and concerns, is Creative Cities Network of Canada (CCNC). CCNC is Canada’s national network to facilitate innovation and creativity in municipal structures. They support cultural development by sharing knowledge between municipalities and enhance social, economic and environmental sustainability. CCNC (n.d.) has provided three different manuals, or toolkits as they call them, on the process of; cultural planning, cultural mapping, and managing public art projects, which are free to download for anyone at their website. Toolkit for Cultural Planning (CCNC, n.d.) refers to

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

cultural planning as a process of inclusive community consultation and decision-making helping local government to identify cultural resources. Both the Swedish manual by Lundberg and Hjorth (2011) and CCNC’s toolkit has step-by-step instructions on how to use cultural planning as an approach.

By examining cultural planning through the three categories, we have uncovered the ideals and values of the concept and are also able to answer our first research question; How is cultural planning conceptualized? In comparison to Florida’s description of the housing bubble in the states, which evidently is not a sustainable way of developing cities and communities, the core of cultural planning demand a more sustainable, dense and social city planning. We believe that the core values of cultural planning is in line with Grogan and Mercer’s statement that cultural life is about participation, identity and a sense of belonging to a place and a community. Cultural planning is both idea and practice based, but we believe that the driving force is and must be the ideology and core values. With ideology we aim at the word’s meaning as a collection of social ideas and beliefs that legitimise chosen actions. Within the concept of cultural planning, these ideas and beliefs are both social and political. Its foundation is as we stated in our abstract; Humans are social beings with a need to interact with each other and public spaces should fill the need of physical space were communities and neighbourhoods can meet. As Landry mentions, we also believe, that for every matter there is appropriate tools, and the wrong ones might limit progress. For example, the issue with the terminology tends to limit the growth of both the network and the concept itself. Instead of focusing on the terms, focus should be on the core values using a common language, which we believe is key in further work establishing the concept.

The city, as a living organism with all its citizens, craves a more coherent and holistic approach. Having a human dimension, civic creativity, social capital and the civic city as starting points for city planning, would assemble the core values of cultural planning. These four concepts are the ones that we have chosen to proceed with since we find them covering the wide spectra and core values of cultural planning, from the human as an individual to the human and its relationship to each other and to the city. We will apply them together with our case study data, which will be discussed more thoroughly in chapter five.

Concept findings; ideology as a driving force

O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

Main focus

ANTI festival

This section renders three case studies we have drawn from presentations transcribed during Nordic Urban Lab 2018 in Helsinki. We will also present an extract of our observation data containing important discussions taking place at the conference, that are central to answer our research questions. We will end this section with another extract containing thoughts that emerged from our meetings with KIT.

The 24 presentations at the NUL conference were all presented by different professionals in the field of cultural planning. Some presentations where more philosophical, others where observational, and some were descriptive; of events that had taken place at different locations. The three presentations chosen for this thesis provide an insight into actual events and give insight into how an existing and functioning network works. Anti-festival and Laimikis are examples and approaches used in two different European countries, and CCNC presents how a network in Canada structures and works with cultural planning. To highlight once more; the transcriptions of the presentations are shortened and reorganized into themes when making the case studies in this thesis. This is the first sorting of the case studies, which we will go deeper in, in chapter five. By having all three case studies following the same division with the four themes; Main focus, The role of the citizens, The role of the city and The relationship between the city and the citizens, we believe that it will be easier to get an overview of each case but also to compare them with each other. The themes speaks to our four concepts which we use later to analyse the case studies, but at this point we want to focus on the signification of the cases without any add-ons.

ANTI - contemporary Art Festival, takes place in Kuopio, Finland. The festival focus on diverse artistic practices, creating diverse encounters in everyday spaces and places. It is open to all sorts of artforms, with artists from any background. The city of Kuopio hosts the one-week long festival, an annual festival since 2002. The projects by artists from all over the world inhabit the spaces of public and everyday life; in homes, shops,

chapter 4

A.F.K

Accessing the Fields Knowledge

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

The role of the citizens

The role of the city

The festival is working with artists across artforms, interested in and responding to current phenomena of contemporary arts. Its framework in the artworld are for example: public art, site-specific art, live art, urban art, and dialogical aesthetics. The festival works a lot with projects that encourage participation of all kinds of people and communities, through arts in everyday environments. Engaging people in the making, creation, and presentation of their works. Mission and vision for working with the city of Kuopio is to foster a vibrant, urban culture. The festival want to promote the presence and visibility of different communities and minorities, which in this small-scale Finnish town is not very present in the public life. ANTI festival wants to create diversity of encounters with different kinds of practices, for example:

Durational installation Performative installation Participatory installation Participatory event

Single performative events Intimate, private work

Throughout the festivals’ 16 years, ANTI has been working in three different phases with the ideas of site, of understanding and thinking of space and the city, but also on how artists are woking.

First phase, 2002-2007:

The curators pre-selected sites in the city, and asked artists to respond to those sites. Interested of looking at the structures of the city, how people in different ages and different phases of their life view the city very differently. As an audience member, you got to explore the city in another way than you would normally do in your everyday life, and if you were a visitor of the city, you got to encounter the city in another way than the “normal” tourist narrative of what is attractive in the city. Also to activate and highlight the city, and “non places” through art.

Second phase, 2008-2014:

Started to work in dialogue with artists to select sites, and extending the sites to communities; existing and emerging communities, virtual and city squares, forests and lakes. The festival directly engages communities and audiences in the making and showing of their work. The name of the festival; ANTI, has a double meaning. Anti - as in ‘kind of against’ something or ‘kind of an alternative’ to something, and as anti in Finnish - which means a gift. A gift to the city and the citizens; all the events are also free to attend.

O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

all kind of temporary communities. Also asked the artist to respond to themes. More participatory artwork, engaging citizens and communities, related to the social terms of art that the artist became interested in. Working with people, making works that uses people as material and medium of the work.

Third phase, since 2014:

Since 2014 ANTI are working in close collaboration with partners outside the artworld. A partnership model they call Partnership 3.0. The partner can be another organisation or a company. This partnership creates the festival theme (2015 the theme was “Fun run” and the partner was Kuopio Marathon). Extending the presence of the festival to other sectors, creating new audiences, and strengthening the value and visibility of art in the society. Developing new working structures and models of collaboration. The element of dialogue becomes very strong throughout the whole festival structure. Brings new unexpected things to the work. Some examples of these partners and themes are:

2015: Kuopio Marathon, running, sports, endurance

2016: Winter, in collaboration with actors at the skiing centre

2017: Water, in collaboration with e.g. Our Water-Conscious Land project, and the local water company

2018 - upcoming. Play, Games, Gaming. In collaboration with Games for Health Finland and International Game Developers Association Kuopio Hub

Figure 2. Artist: All the Queens Men at the ANTI - Contemporary Art Festival. Photo by Pekka Mäkinen

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

Producing space creates immediate impact on audiences and participants but also transforms the city over time. It increases active cultural participation; letting people become creators, co-creators, and adds layers to the city map, affecting how public spaces are used; what is allowed and by whom.

The relationship between the city and the citizens

The role of the citizens

Urban games can function as an alternative system of navigation in public space. It can expand our ability to act in space. It has the capacity to change the collective behaviour. We need to practice our ability to be free from rational boxes and intervene our routine structures. We need to use things in more spontaneous ways. We need interactions! When we go out, and take the same route every day, our experience narrows. In a sense we limit ourselves from new expressions and it’s easy to be blind for our nearest surroundings. Let’s explore the city we visit, live and reside in. By following the rules of an urban game, it challenges you to move and look at the environment in a different way of which that you are used to.

- Jekaterina Lavrinec, NUL, Helsinki 2018

“Games are a very powerful tool, because you can change your social background”

The context of urban games can vary; different kinds of playful, interactive urban games in different places and cities. But they all have the social interactions, shared interests, new roles and new interconnections in common. Combining things that one may think is uncombinable, to expand our understanding of public space, and to engage people into

Laimikis

Main focus

Laimikis is a laboratory for urban games and research, aiming to engage public spaces in a playful way. The aim is to use urban games as an approach to research the full potential of public spaces, both socially and spatially.

Defining what a game actually is and its requirements;

Space. Somewhere where the game can take place, whether it’s physical or virtual.

Time. A duration and/or regularity Rules. A sort of behaviour models.

Participants. Different roles and involvement.

- Jekaterina Lavrinec, NUL, Helsinki 2018

“To share our time together, is the most valuable resource we have.” O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

Examples on how to combine the spatial and social in a playful way: Go Micro!

Micro-practices are a light form of sociality. People understands one another’s micro gestures unconsciously. We have a collective consciousness in terms of an unspoken set of rules on how to behave in public spaces. This becomes clear when someone breaks these unspoken rules, by for instance being very loud or uses big gestures. Therefore, micro-practices can be very small, but also very effective in creating a reaction.

Examples on micro-projects that has been practiced in the public space; - The tweenbot, which was an experiment at Washington Square Park, NY, 2012, by Kacie Kinzer. The tweenbot was a miniature robot that could only move in one direction, forward, and the experiment was to see how many people would interact with, or help, the robot in its journey to crossing the square. This was also interesting from a sociological point of view, since the interactions between humans became visible through a physical object. The humans were interacting together through the robot. - Micro-protest (figure 3) was a project, which aimed to engage the citizens, and give their ideas on how to change Lukiškių square, Vilnius, 2012. The idea was to let any by-passer write a message on miniature signs. The material attracted pigeons, so people started to write messages as; power to the pigeons! So, it became a fun and humoristic way to involve the citizens.

Go Macro!

Not only micro-practices can influence the use of public space. To go macro can be an effective way of for example protesting, putting up big-scaled letters in a specific site. Going macro with moveable big letters can also be a way to reconfigure space, in a sense, bringing the place with you. Tangible text is a playful design, which can invite to interaction. Street Komoda

Vilnius, 2012. Based on the idea; take something - leave something. The komoda was an urban furniture designed as a site-specific object, a sort of drawer/cabinet that had similar material as its surroundings. It is a place to share things. It ended up being taken care of, and promoted

The relationship between the city and the citizens

exploring more than they are used to. Also, to understand the connection between the social and the spatial. Games need space, and urban scenography can be changed, depending on how the people are using the space. An object can make people stop, but the object needs people to interact with it, in order to affect the choreography and navigation of a space. By co-adjusting public space, we set certain types of relations. Social practices are spatial, they are embedded in space and creating the public space. For example, a notice-board can create a meeting place, because it is an indication to stop.

O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

The role of the city

URBINGO - Cooperation as a craft

URBINGO, invented by Laimikis, is a matrix for collecting stories and images of the changing neighbourhood. The game is actively used, and you play with visual cards that gives you smaller missions, to find something or to interact with someone. If you start approaching people you rearrange the social space! Urbingo focuses on the eye-level, how do you see the city? How do you experience it? It makes people to slow down going through the cities and areas, but also encourages to walk more. URBINGO opens the neighbourhood and the number of fans is growing. Wherever you go, there is something to see. The game is giving a reason for people to go somewhere and to remote neighbourhoods. It is analogue, but the sites in the game are photogenic so social media are included in an indirectly way. It is also connected to emotions, because when you start to collect things in the game, you get involved and passionate. Right now, it is used mostly by families and youngsters, whilst elderly have provided stories for places. When the game was created, it was the locals that were the basis providing the stories.

by, some people who were practicing parkour in the nearby area. A local music band used the komoda to promote their music. It became a spot to stop and talk, a meeting place.

Open Code urban furniture

Inspired by the well-known game Tetris. This project was workshops in co-design in four different neighbourhoods in Vilnius. The aim was to create playful spaces, allowing people to arrange the space as they needed. It was also a research project, in terms of what materials and design to use in public furniture and how to establish trust and safety. For example, in some blocks, there were drawers, but in some areas, they didn’t want drawers because the fear of what people would put there, trash etc. It was also a research project in the process of co-development on how to use co-design as a tool in public space. People also had their own ideas on how to use them, for example some children wanted painted chessboards on the modules.

Figure 3. Micro-protest, picture from Laimikis homepage. O.M.G B.T .W W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K

CCNC has developed three different kinds of toolkits; Cultural Mapping Toolkit, Public Art Toolkit and Cultural Planning Toolkit, of which the latter one is the one described in this case study. The toolkits can be found and are free to download on CCNC’s webpage and are targeting community leaders, organizations, local government staff, elected council members and partner organizations.

In the toolkit of cultural planning, a set of arguments are presented of why cities need a cultural plan. For example; a cultural plan can help with combatting the social exclusion of a community and to tackle the “geography of nowhere” by supporting local community initiatives to provide a sense of pride of their place. By supporting, encouraging and promoting local involvement, cooperation and ownership, it can identify the community needs. Logically, different cities need different cultural plans. The main purpose and priorities needs to guide you in which direction your cultural plan should go. In order to choose the right plan for a place, it might help to consider the following questions: Do you need to develop a comprehensive detailed cultural plan which broadly defines the understanding of culture? Or do you need a framework plan which is aimed more towards a goal in the long run? Or maybe you need a specific short-term plan that has mainly a single focus, such as the art sector, heritage or tourism? The toolkit aims to help with these issues.

The Cultural Planning Toolkit

Preparation is the first step in the cultural planning toolkit and cannot be underestimated. The toolkit encourages you to think about your community’s definition of culture. Cultural planning is a dynamic and emergent practice, which challenges presumptions and long accepted vocabulary. Words can mean different things for different people and language is something that should be highly considered in the cultural

The role of the citizens

The role of the city

CCNC

Creative Cities Network of Canada (CCNC) is Canada’s national network to facilitate innovation and creativity in municipal structures. They support cultural development by sharing knowledge between municipalities and enhance social, economic and environmental sustainability. Every province has its own provincial ministry of culture, and these does not always align. For example; Oakville is a part of the Halton county, including five other cities, which has its own plan, which need to fit in the provincial frameworks, and at a national scale. This add a lot of complexity. Mandate for culture is often split, and municipalities have a big range in size. Resources & organizational structures are extremely diverse and the expertise and training in cultural planning are limited.

Main focus O.M.G B.T .W F.Y .I W .O.W F.T .P A.F .K