Does CSR really influence

Millennials’ purchase

decisions?

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 credits PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Marketing AUTHORS: Sanna Moresjö and Yue Xin JÖNKÖPING May 2020A qualitative study on attitudes toward the

fast fashion industry

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Does CSR really influence Millennials’ purchase decisions? Authors: S. Moresjö and Y. Xin Tutor: Darko Pantelic Date: 2020-05-18 Key terms: CSR, Fast fashion, Purchase decisions, Millennials, Emerging marketsAbstract

Background: The phenomenon of CSR has become an increasingly adopted strategy among companies, as a result of the frequent discussion on climate change. At the same time, consumers have attained further awareness regarding sustainability and how consumption impacts the environment. Further, the fast fashion industry has been highlighted as one of the most harmful and unethical industries that negatively impacts the environment and lives of all. Thus, it is interesting to explore which factors influence consumers’ purchase decisions, and determine whether sustainability and CSR are taken into consideration. Purpose: This thesis aims to explore millennial consumers’ attitudes toward Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), as well as which factors consumers take into consideration when they are making purchase decisions.

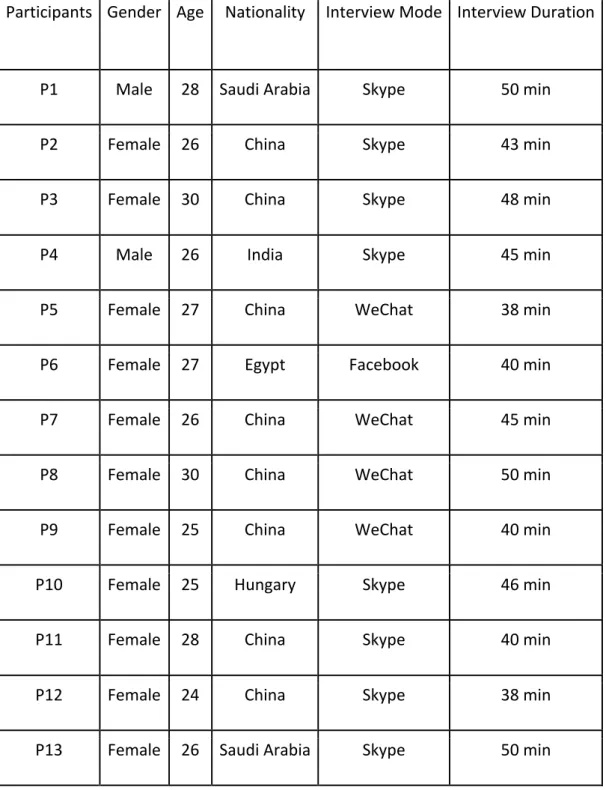

Method: In order to meet the research objectives, data has been collected with

exploratory and qualitative methods. The research philosophy follows interpretivism, and adopts an abductive approach. Furthermore, 13 semi-structured interviews were conducted, which aim to explore and provide and understanding for consumers’ attitudes and perception. Interview participants were selected based on a purposive sampling method, with two identified criteria. Additionally, a coding system was constructed based on the literature review, which was used to analyse the data collected from the interviews.

Conclusion: The results, extracted from the empirical data and analysis, suggest that there

are two categories with factors influencing millennial consumers’ purchase decisions. The first category includes product related factors, whereas the other category includes a number of consumer related factors. The empirical results further conclude that the participants generally experience positive attitudes toward sustainability and CSR, while product related factors are more influential in the decision-making process.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our gratitude and appreciation to everyone who supported us during the process of writing this master thesis.

Firstly, we would like to thank our supervisor Mr. Darko Pantelic, Assistant Professor in Business Administration at Jönköping International Business School, for providing guidance and valuable feedback throughout the research process. Secondly, we would like to thank our peers for providing constructive feedback during the seminars. Lastly, we would like to thank the 13 interview participants, who generously dedicated their time and effort to share their views and experiences with us, and without whom the study would not have been possible to conduct. Kind regards, ___________________ ___________________ Sanna Moresjö Yue Xin Jönköping International Business School May 2020

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Problem discussion and Purpose ... 4

1.3 Research Questions ... 5

1.4 Methodology ... 6

1.5 Limitations and Delimitations ... 7

1.6 Keywords ... 7

2. Literature Review ... 9

2.1 Consumer Behavior ... 9

2.1.1 Attitude-Behavior gap ... 10

2.1.2 Factors influencing attitude and behavior ... 12

2.2 Corporate Social Responsibility ... 17

2.2.1 Triple Bottom Line ... 18

2.3 Fast Fashion ... 21

2.4 Emerging Markets ... 24

2.4.1 Millennials’ Characteristics ... 26

2.5 Conceptual Framework ... 27

3. Methodology ... 30

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 30

3.2 Research Approach ... 32

3.3 Research Design ... 33

3.4 Data Collection ... 34

3.5 Sampling ... 36

3.6 Execution of Interviews ... 37

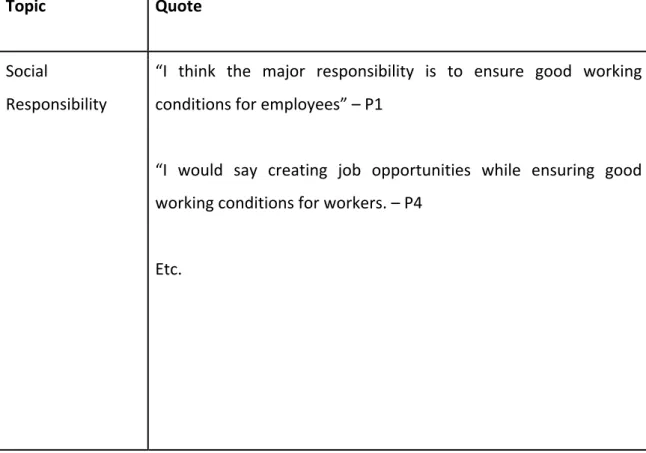

3.7 Research Instrument ... 39

3.8 Data Analysis ... 40

3.9 Quality of Research ... 41

3.10 Ethical Considerations ... 42

4. Empirical findings and Discussion ... 43

4.1 Participants’ Introduction ... 43

4.2 Attitudes toward Fast Fashion ... 45

4.3 Attitudes toward Sustainability ... 46

4.5 Critical Factors influencing Purchase Decisions ... 56

4.5.1 Product related factors ... 56

4.5.2 Consumer specific Factors ... 61

5. Conclusion ... 68

5.1 Evaluation of the Research Questions ... 68

5.2 Managerial Implications ... 73

5.3 Limitations and Delimitations ... 74

5.4 Future Research ... 75

References ... 80

List of Figures

Figure 1 TRA and its components ... 11 Figure 2 TPB model and its components ... 12 Figure 3 Critical factors affecting millennials’ purchase decisions ... 71List of Tables

Table 1 Countries classified as Emerging Markets ... 25 Table 2 Participants’ profile ... 38 Table 3 Example of data categories ... 41List of Appendices

Appendix 1 ... 771. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The following chapter provides a brief background to generate a basic understanding of the topics the research will address. Further, it introduces the problem discussion and purpose, as well as the research questions that the study aims to answer. Delimitations and limitations are established, in addition to a list of keywords with definitions that aims to provide guidance for the reader.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

Over the past years, the phenomenon of climate change has become one of the most frequently debated topics. As a result, sustainability has become the center of attention to foster development that reduces negative impact on the environment (Werther & Chandler, 2011). This thesis is focused on how businesses incorporate the issue of sustainability, which in this context translates into Corporate Social Responsibility (hereafter CSR). Werther and Chandler (2011) claim that the increasing demand for CSR and sustainable business practices is one of the most influential factors impacting companies in the 21st century.

The modern perception of CSR was introduced as early as in 1953, when Howard Bowen published his book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. Although numerous definitions of CSR have emerged over time, the essential interpretation remains equivalent to Bowen’s concept and broadly focuses on corporations’ responsibility and relationship towards society (Bowen, 1953; Carroll, 2015; Porter & Kramer, 2006). Bowen (1953) claims that businesses’ actions, decisions and policies affect the prosperity and lives of all, and companies are thereby obligated to take society’s needs into concern. In addition to social responsibility, CSR also involves two other aspects: environmental and economic responsibility. Elkington (1999) introduces these three dimensions as the Triple Bottom Line and defines that a social responsible

corporation is assumed to include activities that enhance social equity, economic prosperity, as well as environmental protection.

In the Western part of the world is CSR nowadays considered as the centerpiece in business ethics and has become a necessity for businesses to adopt in order to remain competitive (Carroll, 2015; Moratis, 2016; Porter & Kramer, 2006). Stakeholders are expecting that modern companies do more than make money and obey laws, investing in CSR activities can therefore improve company reputation and image towards stakeholders (Schaltegger & Burritt, 2018; Porter & Kramer, 2006).

Nevertheless, the importance of sustainability varies around the world, and so does companies’ involvement in CSR (Urip, 2010). Evidence shows that emerging markets are still behind when it comes to implementing CSR activities, while the Western countries have become standard-setters (Gugler & Shi, 2009; Matten & Moon, 2008; Zamir & Saeed, 2018). National institutional frameworks contextualize one of the reasons for why CSR differs among countries, whereas “institutions” refers to governmental organs, organizations, as well as formal laws and regulations (Matten & Moon, 2008; Jamali, Lund-Thomsen & Jeppesen, 2017). Furthermore, the scope of socially related involvement is often driven by political, economic, social and cultural views of a country, which affect the variety of CSR activities in different countries (Matten & Moon, 2008; Urip, 2010). Therefore, the implementation of CSR activities may be challenging in emerging markets if the country is characterized with weak law enforcement, low education level, high poverty rate, as well as occasional financial and political instability (Urip, 2010). As a result of the increasing attention sustainability and related issues has been given, many industries are nowadays under the watchful eye of the public. The fast fashion industry is one of those, as it ranks as one of the world’s most polluting sectors contributing to severe issues (Shen et al., 2017). CSR and sustainable business practices are therefore particularly important to adopt in the fast fashion industry. Furthermore,

the fast fashion industry is a highly globalized sector, which is associated with mass-production, rapid lead times and low prices (Caro & Martínez de Albéniz, 2015). It is also a sector that has faced an enormous amount of criticism in terms of sustainability challenges, and is therefore characterized with a bad reputation (Perryer, 2019; Shen et al., 2017). From consumers’ perspective, fast fashion allows them to purchase fashionable and trendy clothes at a low price, which can be worn for a while and then thrown away (Byun & Sternquist, 2008). However, in order to remain competitive and sell fashion at a low price, fast fashion companies tend to fail at social and environmental responsibilities (Choi et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014). One major issue with fast fashion is its negative ecological footprint, mainly in terms of pollution, water usage and transportation emission (Perryer, 2019; Shen et al., 2017). In addition, as companies try to produce clothes as cheap as possible, labour practices are often endangered and violating human rights (Choi et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014).

The fast fashion industry has become increasingly important to the world economy, particularly in terms of revenue from export (Gabrielli et al., 2013). However, consumers have started to grasp the negative outcome of consumption and its impact on the environment. Consequently, expectations of brands and products are becoming increasingly higher, to meet consumers demands without causing negative impact on the environment (Perera et al., 2018; Kostadinova, 2016). In order to maintain consumer’ traffic and sales, brands need to re-strategize and strengthen their ethical reputation, which can be done by adopting CSR strategies (Hur Kim & Woo, 2014; Bhattacharya & Sen, 2004).

In addition to the fast fashion sector, this research is focusing on the millennial’ segment. Millennials are different from other generations; they shop differently, engage with brand differently, and first and foremost, they hold brands accountable more than any other generation (Chong, 2017). When it comes to sustainability and preservation of the environment, millennials are arguably the most concerned generation (Farrell, 2019). It is also the segment that tends to spend more money on products from companies engaging in CSR (Peretz, 2017). Furthermore, the millennial generation was born in the digital era and is accustomed to social media, where they

are exposed to large amount of misleading information and fake content (Abramson, 2018). As a result, millennials are already aware of how to filter information and are more likely to doubt the authenticity and real motivation behind a brand (Feldman, 2019). Millennials' skepticism about corporate motivation has given rise to a new and overwhelming demand and desire for CSR (Chong, 2017). Millennials will not blindly purchase from companies with unclear intentions and questionable operations, but strongly support those with high transparency and a clear contribution to society (Agrawal, 2018). In addition, millennials are more likely to put effort into researching what issues a company supports and to which extent the company contributes (Chong, 2017).

1.2 Problem discussion and Purpose

As a result of the growing demand and attention CSR has received in recent years, there is a wide variety of research existing on the phenomenon. Previous studies are mainly focusing on the positive advantages firms can attain by implementing CSR activities, particularly in terms of intangible attributes e.g. brand image and company reputation (Lii & Lee, 2012; Porter & Kramer, 2006; Schaltegger & Burritt, 2018). Another frequently researched area is the correlation between CSR and competitive advantage, suggesting that companies’ CSR strategies can strengthen relations with stakeholders, which ultimately generates increased competitiveness and profitability (Porter & Kramer, 2011; Schaltegger & Burritt, 2018).

Nevertheless, the rapidly growing importance and demand for CSR also present some relevant issues, in particular when companies position themselves as ethical to emphasize a positive image towards stakeholders, while in reality it is merely a marketing trick (Porter & Kramer, 2006). This matter raises questions among consumers, particularly in terms of ethical motivations behind CSR, and whether companies are credible and transparent with their strategies (Schaltegger & Burritt, 2018; Kim, Hur & Yeo, 2015).

As previously mentioned, CSR is particularly important in the fast fashion industry as it ranks as one of the world’s most polluting sectors (Shen et al., 2017). While studies have shown an increasing attention among consumers towards ethical behavior in the fast fashion industry, most researchers have focused on the supply chain and business process of the industry (Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). There are only a few studies investigating young consumers' attitudes towards CSR and ethical business practices, and the ones existing are focusing on the United States and Europe, while little attention is given to emerging markets (Amaladoss & Manohar, 2013).

The research conducted in this thesis will therefore strive to fill the existing research gaps, by exploring millennials’ attitudes toward the fast fashion industry and CSR, from an emerging market perspective. The outcome of the study may therefore give companies, within the sector, a better understanding for what their consumers’ values and how those values influence their purchase behavior. In addition, the research may support companies’ CSR strategies and marketing communication, as the findings and result will indicate whether consumers take sustainability into concern when making their purchase decisions. Meaning that based on the results, it can be further anticipated whether fast fashion companies’ ethical initiatives actually pays off.

1.3 Research Questions

In order to further close the existing research gaps, the research will focus on the following research questions, which have been formulated to structure the study:

RQ 1: What are millennials’ attitudes toward fast fashion?

Although the fast fashion industry is a popular clothing segment, it also presents several ethical concerns, which have become increasingly discussed. Therefore, this research question aims to identify and generate an understanding for millennials’ attitudes toward fast fashion, and gain insight to previous experiences with the

industry. This question will provide a basis upon which the other research questions rely on. RQ 2: What are millennials’ attitudes toward sustainability and CSR? This research question dives deeper into millennials’ ethical values, in order to uncover attitudes and perceptions of sustainability and CSR. This question is undoubtedly significant for this research as it serves as the foundation of the purpose.

RQ 3: Which factors affect millennials’ decisions when purchasing fast fashion?

Within this question, factors and values are explored, in order to generate an insight to why and how millennials make their purchase decisions. For instance, literature has introduced factors such as price and quality, which may be applicable as common factors. Thus, the authors of this thesis seek to identify additional factors influencing millennials’ decisions.

1.4 Methodology

The thesis is conducted through an exploratory approach and qualitative design, in order to attain a deeper insight to millennial’ attitudes and perceptions towards CSR in the fashion industry. Furthermore, the data is collected both primary and secondary. The secondary data is gathered to provide a foundation of the research in order to identify all the relevant elements and research gaps, as well as to establish a theoretical background. As the research aims to reveal perceptions and attitudes of millennials, primary data is gathered by conducting semi-structured interviews. The interviews are conducted with a purposive sampling, focusing on millennials from emerging markets.

1.5 Limitations and Delimitations

The study presents some limitations and delimitations existing. Firstly, limited resources and time resulted in a limited sample size for this study. Secondly, due to the Convid-19, all of our interviews were conducted through Skype, WeChat and Facebook. This kind of online interview may provide less rich communication context, impairing the length of interviews and our ability to capture non-verbal communication cues. Thirdly, ethical topics, such as environmental and social issues are highly sensitive, which may cause many people to answer questions in a socially desirable way. Lastly, the study takes place in Sweden and not the participants’ domestic country, which could influence their attitudes and perceptions. If the study was conducted in emerging markets, the outcome could possible differ.

In addition to these limitations, the study is conducted with some deliberate delimitation as well. The study adopts purposive sampling and focuses on participants born in the 1990s (millennials). Furthermore, as the study is concentrated on emerging markets, the participants need to origin such countries. Therefore, other age range and nationalities have been disregarded. In addition, this thesis is written from consumers’ point of view rather than from companies’ perspective. 1.6 Keywords

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) – “ The responsibility of enterprises for their

impact on society” (European Commission, n.d.), and “Companies become socially responsible by integrating social, environmental, ethical, consumer, and human rights concerns into their business strategy and operations” (European Commission, n.d.)

Fast fashion industry – “The fast fashion is a segment within the fashion industry,

which focuses on mass-producing clothes with cheap labor and manufacturing costs, in response to the latest trends” (Perryer, 2019).

Triple bottom line – “A framework recommending that companies commit to focus

on both social, environmental and economic responsibilities of the business, in order to become long-term sustainable” (Elkington, 1999).

Emerging market – “Was originally coined by the International Finance Corporation

(IFC) to describe a fairly narrow list of middle-to-higher income economies among the developing countries, with stock markets in which foreigners could buy securities. The term’s meaning has since been expanded to include more or less all developing countries” (Pillania, 2009).

2. Literature Review

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The following chapter discusses relevant theories and existing studies, forming a foundation of the research. The chapter is divided into five different subchapters. Firstly, general consumer behavior is introduced, along with factors that influence consumers’ attitudes and behavior. Secondly, CSR is further explained using the framework Triple Bottom Line. Thirdly, fast fashion is discussed by introducing advantages and issues of the industry. Fourthly, emerging markets are presented, as well as the generation of millennials. These elements aim to create a frame of reference for the research. The chapter sums up with a conceptual framework, which combines the topics within the thesis together with the formulated research questions.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Consumer Behavior

The global trend of sustainability has not only promoted CSR growth, but has also drawn consumers’ attention to the topic (Perera et al., 2018). The ongoing debate regarding how consumption negatively impact our planet has resulted in a wave of changing consumer patterns, as consumers have started to grasp the impact of their behavior (Perera et al., 2018; Kostadinova, 2016). The trend and increasing awareness of sustainability and CSR has driven consumers to become more ethical and conscious in their consumer behavior to reduce their negative impact on society (Perera et al., 2018). As an outcome of the wave of behavioral change, concepts such as ethical consumption and conscious consumerism have become widely implemented in literature and research (Perera et al., 2018). These concepts suggest that consumers take social and environmental concerns into consideration when making purchase decisions (Freestone & McGoldrick, 2008; Papaoikonomou, 2013). Therefore, research conducted over the past decade has shown that consumers tend to have a positive behavioral response towards companies engaging in CSR (Wang et al., 2015; Rim et al., 2016; Joshi & Rahman, 2015).

The traditional consumer’ decision-making process is often illustrated as a four-step procedure. In the first step, need recognition, the consumer recognizes a problem or a need that he or she wishes to find a solution for (Solomon, 2015). The second step, information search, is a process where the consumer researches various alternatives and seeks information in order to make the best possible decision (Solomon, 2015). In the third step, the consumer evaluates the information he or she has obtained from the previous stage. In the last step, the consumer makes a product choice based on the previous three steps (Solomon, 2015). While the new era of ethical consumer’ research, suggests that the decision-making process may still follow the traditional four-step procedure, it further claim that consumers’ attitudes toward sustainability issues increasingly impact the product choice (Freestone & McGoldrick, 2008; Papaoikonomou, 2013). This means that when consumers screen the market for alternatives, they will more likely seek brands that engage in CSR and ethical business practices (Wang et al., 2015; Rim et al., 2016; Joshi & Rahman, 2015). However, research also suggests that the increasing demand for ethical business practices makes the decision-making process more complex, particularly by emphasizing that consumers’ attitudes are integrated (Bray et al., 2011; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). The next section is therefore focusing on consumers’ attitudes and behavior.

2.1.1 Attitude-Behavior gap

Sheeran (2002) pointed out that attitude can be used to predict various behaviors, while Boulstridge and Carrigan (2000) believed that there is a significant gap between attitude and behavior. Actually, many consumers take a positive attitude towards sustainable products, but most of them will eventually not buy these products (Morwitz, Steckel & Gupta, 2007). In other words, consumers have an sustainable attitude with the willingness to pay extra for ethical products, but only a few consumers take action (Mintel, 2006). Thus, Kim and Rha (2014) believed that attitudes cannot be used to predict behavior very well, especially in terms of normative or ethical behavior. According to the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) by

Ajzen & Fishbein (1980), behavior is determined not only by individual attitudes, but also by subjective norms. As shown in the Figure 1 below, behavior is affected by intention, which is determined by attitudes to behavior and subjective norms. People’s attitudes toward behavior describe their expectations and personal assessment of possible behavior (Ajzen, 1985). These behavioral beliefs come from existing experience and perception (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Individual perceptions and behavioral intentions are very subjective, so different people will behave differently, even if they are exposed to the same conditions (Ajzen, 1985; Stroebe et al., 2003). Figure 1 TRA and its components Source: Own design, adapted from Stroebe et al. (2003).

Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) pointed out that the TRA presents some limitations, as it does not consider human’ perceptual control, which also affects the intention to perform certain behaviors. Furthermore, Fishbein and Ajzen (1977) proposed the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), based on the TRA (see Figure 2). In other words, TPB is an advanced version of TRA. Two components are the same: "attitude towards behavior" and "subjective norm", but the TPB presents one additional factor: "perceived behavior control" (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1977). Taking these components into

consideration, it becomes evident how complex the decision-making process is (Park & Lin, 2018). Figure 2 TPB model and its components Source: Own design, adapted from Moser (2007).

In addition to the TRA and TPB, there are several additional factors related to the attitude-behavior gap, impacting consumers’ attitudes and behavior, particularly in terms of ethically produced goods. These factors are outlined and further discussed in the next section.

2.1.2 Factors influencing attitude and behavior

There are several factors that are influencing consumers’ attitudes and behavior, which can be divided into three categories: individual characteristics, product characteristics, and socio-demographic characteristics (Park & Lin, 2018). The following

section aims to further outline and explain each factor to develop an understanding for the how these factors influence consumers.

Individual Characteristics

Motivation: Individual characteristics also have a significant impact on ethical

behavior, particularly in terms of motivation, which is a powerful internal stimulus (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002). Motivation can be a conscious or unconscious driver of consumers' ethical behavior (Geng et al., 2017). According to Geng et al. (2017), motivation can be defined as the direction of a person's behavior, or the reason why a person wants to repeat an action. Motivation drives an individual to perform or even repeat behavior in a certain way, or at least to develop an intention for a particular behavior (Geng et al., 2017). In addition, motivation is generally influenced by specific drivers and barriers (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002). The motivation of ethical behavior depends more on people's initiative, which can encourage individuals to reduce or even give up other needs that damage the environment and society (Geng et al., 2017). Instead, the barriers can reduce the motivation of the environmental behavior if the barrier is stronger than the green motivation (Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018).

The norms and personal responsibility: The norms and personal responsibility can be

additional powerful influences. According to Stern's Value -- Belief -- Norm Theory (Stern et al., 1999), the norms make people feel obliged and responsible to support activities beneficial to the environment and society(Burke & Davis, 2014). The people with high levels of personal responsibility are more likely to engage in ethical behavior (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002).

Awareness and knowledge: Awareness and knowledge of ethical behavior can also

affect consumers' behavior, as one must be familiar with related problems and causes in order to take measures (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002). Furthermore, Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002) emphasize the importance of basic knowledge regarding environmental and societal issues in order to adopt ethical and conscious behavior. Traditionally, the consciousness of ethical behavior has been mostly examined for its

impact on green behavior (Zavali & Theodoropoulou, 2018). Consumers who are concerned about how consumption affects the environment and its surroundings are more likely to adopt ethical behavior, and thereby purchase “green” products and engage in recycling (Lee et al., 2014).

Skepticism: Some consumers are skeptical toward sustainable business practices, as

they do not believe that the ethical behavior of the company can have any positive impact on the people, society or the natural environment (Bray et al., 2011). Companies’ ethical claims are regarded as a marketing strategy, used to misguide consumers (Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). On the one hand, consumers are skeptical of the impact of their actions, as they do not believe that their behavior will have a great impact on the environment and society. And on the other hand, consumers are skeptical of the motivations behind companies sustainability’ practices and CSR policies (Bray et al., 2011; Burke et al., 2014). In addition, products that are made in a sustainable manner are normally more expensive than other products (Bray et al., 2011; Burke et al., 2014). Consumers are therefore skeptical and questioning whether the extra money paid are used for a good cause, or if it is a ploy (Bray et al., 2011).

Emotional involvement: Emotional involvement refers to the emotional relationship

between people and nature (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002). The emotional involvement affects values and attitudes, as well as the ability for people to have an emotional reaction when they are faced with ethical issues (Chawla, 1998). For example, when a person has a deep affection for the natural environment, he or she is more likely to show ethical behavior, and purchase sustainable products (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002).

Product Characteristics

Price and quality: Product characteristics include price and quality, which often

influence consumers’ buying decision, as consumers consider both price and quality in their purchase process (Alfred, 2013). According to Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002), economic factors have an overall strong influence on people’s decisions and behavior.

process (Bray et al., 2011). In fact, Bray et al. (2011) suggest that consumers tend to care more about financial values rather than ethical values if the price gets too high. Furthermore, consumers are very rational in measuring what they expect to gain from the product or service they buy in relation to the price (Al-Mamun & Rahman, 2014). Product quality is thereby also a critical factor in the decision-making process, as consumers are less likely to make any compromise on quality when purchasing environmentally friendly or ethical products (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001). For example, if a brand provides good quality and a good brand image, consumers will generally think that the brand is worth the price. However, if a brand provides poor product quality, consumers will generally think that the brand's products are priced unreasonable high, and thus, be worthless (Chang, 2015). Thereby, even if a company claims to have ethical activity, most consumers are not willing to pay the higher price if the quality is poor (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005; Didier and Lucie, 2008).

Information: Information of products is one of the factors affecting consumers’

behavior as well. According to Carrigan and Attella (2001), consumers seem to need extensive information in order to make better ethical judgments. Companies are therefore required to communicate this more effectively through the media (Carrigan & Attella, 2001). Many consumers are passive, guided only by external information like price or design, rather than participating in any active search for ethical aspects of the product (Boulstridge & Carrigan, 2000). If ethical issues are to be considered in consumers’ purchasing decisions, consumers need to get more information so that they can easily compare the ethical behavior of different companies and their products (Carrigan & Attella, 2001). Social-demographic Characteristics Gender: According to Parker (2002), female consumers are more sensitive to ethical behavior and are therefore more likely to pay more money for it. Compared to males, females usually do not have as much knowledge about the environment or sustainability, but are more concerned about emotional investment and environmental harm, and are more willing to change (Parker, 2002). According to

Zavali and Theodoropoulou (2018), female are generally stronger green consumers and adopt more green behavior than men.

Age: Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002) emphasize the importance of basic knowledge

regarding environmental and societal issues in order to adopt ethical and conscious behavior. Age is therefore also associated with ethical behavior, mainly because of the increasing educational level among younger people and their knowledge of environmental and societal issues. Age and education are generally good predictors of ethical behavior (Zavali & Theodoropoulou, 2018). Furthermore, studies have shown that people with higher levels of education show a greater willingness to take ethical actions (Diamantopoulos et al., 2003). Suggesting that these people are more willing to promote ethical behavior, as they grow older (Zavali & Theodoropoulou, 2018). But higher educational level does not necessarily mean increased willingness of ethical behavior (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002).

Social and cultural factor: Social and cultural factors also play important roles in terms

of influencing people's behavior. For example, environmental protection behavior largely depends on cultural and social background within the country (Bucic et al., 2012). Previous research has found that this is crucial for buying behavior of ethical products (Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). Environmental awareness has different status in every country. For example, both the different economic development ability and the different education level of citizens can affect the environmental awareness. In addition, social culture influences behavior as well, which can affect individual values and personal lifestyles in varying degrees (Bucic et al., 2012). As mentioned in the age factor, the culture of young groups tends to pay more attention to fashion, price and brand image than to ethical or environmental factors (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018).

The literature in this section shows that consumers’ consumption and behavior is resulting from the interaction between individual, social and cultural factors, as well as products attributes. This thesis aims to incorporate consumer’ attitudes and behavior

together with CSR and the fast fashion industry, to establish insight to which factors influence purchase decisions. The next section is therefore focusing on CSR.

2.2 Corporate Social Responsibility

Over the past decade, CSR has received worldwide attention among managers and researchers as a result of the growing debate regarding sustainability (McWilliams et al, 2006; Garriga & Melé, 2004). Globalization and increased international trade have generated a new demand for transparency (Elkington 1999; Jamali & Mirshak, 2007), which forces companies to earn profit without harming the environment (Savitz & Weber, 2014). Elkington (1999) further explains the growth of sustainability in the business world as a result of multiple waves of change, which arise when society’s expectations reshape. In order to embrace sustainability, business people adopt the concept of CSR, which refers to a corporation’s obligations to the planet and society (Savitz & Weber, 2014). Porter and Kramer (2006; 2011) identify CSR as a way of building shared value, which involves creating economic prosperity while also addressing societal needs and challenges, and by doing so, businesses create value for societies where their operations take place.

While companies take their responsibilities toward becoming more sustainable, similar strategies are implemented on an institutional level as well. For example, the United Nations has established the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, which is a plan of action to enhance prosperity, planet and people (United Nations, 2015). Additionally, 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) has been developed In order to fulfill the purpose of the agenda and transform the world to a better place, which include a) ensuring prosperity and fulfilling lives for all human individuals and that economic progress is developed in harmony with nature (prosperity), b) protecting the environment from degradation and combat climate change through sustainable consumption and production (planet), and c) ending hunger, poverty and inequality in all countries (people) (United Nations, 2015).

The association between companies and their responsibilities toward the planet and society can be further explained by using Elkingtons’ (1999) framework, the Triple Bottom Line, which is outlined and discussed in the next section.

2.2.1 Triple Bottom Line

Elkington (1999) constructed the framework of Triple Bottom Line (hereafter TBL), to help companies separating their responsibilities and adopt proper strategies that are in line with those responsibilities. The framework is based on three dimensions or bottom lines, namely environmental, social and economic, which are further discussed in the sections below. The TBL aims to encourage corporations to become long-term environmentally and socially responsible, in addition to economically sustainable (Elkington, 1999).

Environmental Bottom Line

According to Elkington (1999), the environmental bottom line regards the respect companies should have towards the environment where business operations are conducted and performed. Respect in this context refers to minimizing the business operations’ ecological footprint and preserving natural resources (Pedersen, 2010). The environmental aspect of CSR has become the most debated in recent years as a result of climate change, which has forced governments to establish more strict policies and regulations (Rogelj et al., 2016). The Paris Agreement, which entered in force in 2016, is one example of a global treaty that aims to increase efforts to combat climate change (Rogelj et al., 2016; European Commission, 2020.). Approximately 190 countries signed the agreement and have thereafter set up national action plans and policies to contribute to the goal of becoming environmentally sustainable (European Commission, n.d.). As a result of these new policies and regulations, as well as the raised attention environmental issues have been given in media, companies aim to become more responsible and sustainable (Montiel, 2008).

Companies take their responsibility towards the environment by reducing pollution and carbon emissions in their operations, conserving natural resources, adopting eco-design practices and life-cycle assessment (Montiel, 2008). Another significant effort companies may adopt is sustainable innovation, which allows companies to produce in a more efficient manner, using less raw material and energy (Lu et al., 2018). These innovations are good for the environment, but may also reduce the total cost of a company’s product and improve its value, thus it “pays to be green” (McWilliams et al., 2011; Porter and Linde, 1995). Furthermore, to aid companies to manage their environmental responsibilities, the International Standard Organization (ISO) has developed an environmental management tool, called the ISO 14000 family. ISO 14001 is the most common standard from the ISO 14000 family, which is a globally agreed standard “ […] that sets out the requirements for an environmental management

system. It helps organizations improve their environmental performance through more efficient use of resources and reduction of waste, gaining a competitive advantage and the trust of stakeholders” (ISO, 2015, p. 1). Furthermore, ISO 14001 is applicable to any

type of business that wishes to become certified in order to become more environmentally responsible (ISO, 2015). The ISO 14000 family also includes global standards in environmental auditing, labeling, performance evaluation, life cycle assessment, and greenhouse gas management (ISO, n.d.).

Social Bottom Line

According to Elkington (1999) the social bottom line regards social capital, which comprises human capital in terms of health, skills and education. The social dimension includes the company’s own human capital, but also embraces overall wealth-creation potential for society (Elkington, 1999). To break down the concept further, the social responsibility involves human rights, employee relations, positive impact on communities, and safe working conditions (Elkington, 1999; Savitz & Weber, 2014). The main objective with social responsibilities is to create value for shareholders and society (Porter & Kramer, 2011; Savitz & Weber, 2014; Swanson, 2018). Carroll (1991) translates the social dimension to philanthropic and ethical responsibilities. The ethical responsibilities embody values and norms about fairness

and justice, which are not required by law but yet expected by society (Carroll, 1991; McWilliams et al., 2006).

The notion of social or ethical responsibilities is based on the utilitarian view, which is founded on the “greatest happiness principle” (Crane & Matten, 2016). The principle entails making the greatest good for the greatest number, which is applicable when companies evaluate positive and negative impacts of their initiatives, operations and decision-making (Crane & Matten, 2016). Furthermore, Bénabou and Tirole (2010) claim that companies frequently fails with their social responsibilities by making decisions that increases short-term profit, but disregard the loss of shareholder’ value, as well as the negative effects workers experience. In return it may become difficult to attract the right employees and relations and harm established relations with suppliers and investors (Bénabou & Tirole, 2010). Companies should therefore consider the social responsibilities as a priority in order to accomplish benefits in the long run, specifically to gain stakeholder’ loyalty (Bénabou & Tirole, 2010; Carroll, 1991). The philanthropic responsibilities include promotion of human welfare and goodwill, which companies can embrace by donating financial resources to e.g. education and the community (Carroll, 1991). Carroll (1991) further maintains that while ethical responsibilities are expected by society, philanthropic activities are desired by society.

Economic Bottom Line

The economic dimension of the TBL regards a company’s numerical data, which is analyzed and forms profit and accounting figures (Elkington, 1999). In order to become long-term economically responsible, companies are recommended to consider their competitiveness of costs, as well as whether the demand of products and services is sustainable (Elkington, 1999). Additional important factors to consider are whether the rate of innovation and profit margins are sustainable. Although the economic bottom line is considered the centerpiece in many businesses, there is a lack of general indicators showing if a company is economically responsible or not. Carroll (1991) adds to the economic bottom line by distinguishing five significant responsibilities companies should strive to accomplish. These responsibilities include maximizing

earnings per share, committing to be as profitable as possible, maintaining a high level of operating efficiency and a strong competitive position (Carroll, 1991).

In addition to the economic responsibilities, Carroll (1991) purposes legal responsibilities are included in the bottom line, as companies are expected to comply with laws and regulations while making a profit. The legal components companies should strive after includes performing in accordance with laws and regulations, as well as providing goods and services that meet legal requirements (Carroll, 1991). Both Elkington (1999) and Carroll (1991) maintain that the dimension of economic responsibility is the foundation of CSR, which upon the other bottom lines rests. More recent research has focused on the relation between CSR and competitive advantage, for instance Porter and Kramer (2006) claim that a well-defined CSR strategy can in fact generate economic prosperity and competitive advantages, if it is correctly implemented into the company’s core business. Additional advantages of CSR are translated into positively influencing corporate image and reputation (Porter & Kramer, 2006; Kim, Hur and Yeo, 2015; Malik, 2014).

This section aimed to introduce CSR and its bottom lines, which are of great importance for the purpose of this research. However, the authors have chosen to focus on the environmental and social bottom lines. Thus, the economic bottom line will not be further mentioned in this thesis. It is reasonable to believe that consumers’ attitudes are stronger toward environmental and societal issues, and less concerned with companies’ economic prosperity. Therefore, the authors of this thesis argue that the economic perspective is of less importance in this study and for its purpose. 2.3 Fast Fashion In recent years, fast fashion has rapidly entered the clothing market, and has become a trend among consumers around the world (Gabrielli et al., 2013). According to Hines and Bruce (2007), fast fashion is “a contemporary term used by fashion retailers to

current trends in the market”. The main purpose of fast fashion’ brands is to identify

the latest fashion trends, and translate those trends into cheaper design and sell to a more cheap and affordable price (Bruce & Daly, 2006). Furthermore, consumers increasing demand of fashion has forced the fashion industry to speed up product updates in order to provide the right products and the right time (Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). The fast fashion segment has therefore become a leader in the fashion industry, as it reacts faster to the rapid market changes in response to consumers increasing and continuously changing demand of new styles (Rocha et al., 2005). Additionally, the fast fashion segment presents fast and affordable designs with a quicker lifetime and turnaround of new styles, which allows consumers to replace the clothes on a more regularly basis compared to other more expensive segments of the fashion industry (Bruce & Daly, 2006). Over the last 15 years, production of clothing has approximately doubled, mainly due to the growing fast fashion industry (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017). Although the overall clothing industry plays an important role in the global economy, both when it comes to import, export and employment of workers, it also presents some issues. The production of fashion, particularly fast fashion, causes huge environmental pollution and energy consumption (Perryer, 2019; Shen et al., 2017). Furthermore, the production of fast fashion generally involves frequent usage of chemicals, including pesticides and dye among others. Pesticides are for example, applied to cotton crops during farming to defend them from damaging insects, weeds and mold, which contaminates the soil (ChemSec, 2020). The dye that is used to color clothes contains heavy metals and chemicals, which often leaks out from the factories into water and soil and thereby contaminates the environment (ChemSec, 2020). The pesticides that are used as treatment of crops and textiles along with chemicals from dyeing represent 20 percent of industrial water pollution on a global scale (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017), which indicates how environmentally harmful the production of fashion is. In addition, fast fashion factories are often located in less developed countries where labor is cheap, and thereafter goods are transported to stores around the world (Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). The transportation generates severe carbon emissions

that pollutes the environment and accounts for two percent of the fashion industry’s negative environmental impact (Global Fashion Agenda, 2017).

The manufacturers of fast fashion clothes are using a variety of materials, including natural materials, such as cotton, as well as artificial synthetic materials, such as polyester and acrylic (Muthu, 2019). It is reasonable to assume that cotton should be more environmentally friendly as it is a natural material. Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, cotton is grown with pesticides, which contaminate soil and water. As a result of people’s growing awareness of the environmental issues pesticides are causing, it has become more popular to use organic cotton, which is produced without pesticides and therefore enhances soil quality and biodiversity (Gardetti & Muthu, 2019). In addition, organic cotton requires less water to produce in comparison to conventional cotton (Gardetti & Muthu, 2019), which is another significant issue in the fashion industry. Producing one kilogram of cotton fibers can require up to 4,300 liters of water, depending on the climate conditions. The extensive use of water in production of textile and clothes ultimately causes water shortages in dry areas (Perryer, 2019; Shen et al., 2017). Although organic cotton is a great substitute for conventional cotton from an environmental point of view, it is more costly to produce, and thereby also more expensive to buy (Gardetti & Muthu, 2019). Moreover, the synthetic materials are made from plastic, which also presents a significant issue. Washing clothes made from polyester and acrylic fabric generates plastic microfibers, which are released into the ocean and creates negative environmental implications (McFall-Johnsen, 2019).

Furthermore, Bain (2016) highlights the inability to recycle used clothes as the primarily challenge in the fast fashion industry. As the whole industry is based on creating trendy clothes with a quick turnaround of styles that consumers can replace frequently, it also causes an extremely low product utilization rate and a high amount of waste (United Nations Environment Programme, 2018; Sajnn, 2019). Of all the clothes that are purchased, less than half of the pieces are recycled, while only one percent of the recycled clothes are turned into new ones (Sajnn, 2019). At the same

time, consumers around the world are buying more clothes, which is taking its toll on the environment. The report written by Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) highlights the lack of technologies that are crucial in order to turn recycled clothes into new pieces, in terms of sorting the collected clothes and separating the fabrics’ fibers. Taking the aforementioned issues into consideration, it becomes evident that the fast fashion industry needs to adapt more sustainable business practices. Thus, brands are required to rethink their production and strategies, and involve CSR to become more sustainable. Consequently, consumption of such products would become less harmful to the society and environment, as the negative effects would decrease. 2.4 Emerging Markets This following section briefly introduces the concept of emerging markets. Since this study is focusing specifically on consumers originating from such countries, it is significantly important to understand what the market classification entails.

Countries that are classified as emerging markets are in an economical transition phase, evolving from developing to developed markets (Cavusgil et al., 2013). The transition phase is resulting from rapid growth and industrialization, which consequently allows the country to 1) start an economic reform to alleviate problems such as poverty, overpopulation and poor infrastructure, 2) increase integration with the global economy, and 3) achieve a steady growth of gross national product (GNP) per capita (Cavusgil et al., 2013). MSCI (2019) classifies 26 countries from five regions as emerging markets, which are applied in this thesis (see Table 1).

Table 1 Countries classified as Emerging Markets

Americas Europe, Middle East & Africa Asia Argentina Brazil Chile Colombia Mexico Peru Czech Republic Egypt Greece Hungary Poland Qatar Russia Saudi Arabia South Africa Turkey United Arab Emirates China India Indonesia Korea Malaysia Pakistan Philippines Taiwan Thailand Source: Own design, adapted from MSCI (2019).

Historically, emerging markets have been associated with unstable politics and corruption and local businesses have frequently utilized their strong relationships with authorities in order to repress competition from foreign companies (Ghauri et al., 2012; Urip, 2010). This generates an uncertain environment for businesses to enter. Similarly, emerging markets have often been characterized with limited socio-economic development, in terms of overpopulation, poverty, and lack of educational skills, etc. (Cavusgil et al., 2013; Urip, 2010). As these risks and limitations are becoming increasingly manageable, emerging markets present enormous opportunities for foreign businesses (Cavusgil et al., 2013; Ghauri et al., 2012). One key factor to consider is the market potential emerging markets hold. About 80 percent of the world's’ population lives in these countries (Cavusgil et al., 2013). In addition, while

the education rate is rising, skilled labor in emerging markets is still relatively inexpensive in comparison to Western countries (Cavusgil et al., 2013).

This section aimed to explain emerging markets to the reader, in order to gain an understanding for how markets are classified as well as their characteristics. Moving on, the next section is focusing on millennials’ characteristics, which present the thesis’ target group in addition to emerging markets.

2.4.1 Millennials’ Characteristics

According to Straus and Howe (1991), there are four generations: the silent generation, the baby boomers, Generation X, and Generation Y which is called millennial generation as well. Furthermore, emerging markets account for approximately 86 percent of the world's millennials, or nearly two billion people (Bordlemay & Barrs, 2017). The influence of wealth creation and the spread of millennial’ consumers, are causing consumer behavior and consumption patterns to change (Bordlemay & Barrs, 2017). Furthermore, although many fast fashion companies still rely on making their biggest revenue in developed markets, emerging markets present an important segment as they provide the greatest growth opportunities in the future (Kraugerud, 2017). In addition, Aktan and Burnaz (2010) claim that the industry is mainly geared towards young consumers, as the segment has more courage and interest in trying new innovations.

Evidence suggests that millennials from emerging markets have different preferences than their parents’ generations, who are primarily concerned with improving their basic living standard (Bordlemay & Barrs, 2017). In contrast, the millennial generation spends more on leisure activities, self-improvement, travel, health, dining out, beauty products and clothing (Bordlemay & Barrs, 2017). The major contrast between the generations’ spendings is mainly a result of the younger population, who has started to have a more active social life and wishes to show their looks to friends (Aktan & Burnaz, 2010). Evidence shows that the millennial generation value fashion more than

therefore influential trendsetters (Aktan & Burnaz, 2010). Furthermore, millennials are more concerned about being socially accepted or recognized by the reference group, and are therefore willing to pay more attention to their appearance and spend more money on fashion-related products (Aktan & Burnaz, 2010; Vieira, 2009). Simultaneously, millennials are arguably the most concerned generation when it comes to sustainability and preservation of the environment (Farrell, 2019). Thus, millennials hold brands more accountable than any other generations, for their ways of conducting business and operations (Chong, 2017). Furthermore, a report from McKinsey & Company (2016) shows that in five emerging markets: Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and Russia, apparel sales grew eight times faster than in Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. McKinsey & Company (2016) explain the growth in emerging markets as a result of a growing middle class, which allow consumers to spend more money on clothes.

2.5 Conceptual Framework

This following section aims to provide a conceptual framework based on the literature review, which serves as the basis for the empirical study. The literature review indicates an increasing demand for fast fashion, as well as a growing concern for sustainability among consumers. In response, it has become essential for companies and brands to adopt sustainable business practices to meet consumers’ concerns and demands. Companies are therefore increasingly engaging in CSR activities, in order to take their responsibilities toward the society and environment. Furthermore, along with consumers’ growing awareness of sustainability and companies’ frequent adoption of CSR, research and literature have expanded on the topic as well. Nevertheless, the previously identified research gap implied that literature has given little attention to young consumers’ attitudes toward CSR and sustainable business practices specifically in the perspective of emerging markets. In order to fulfill the purpose of this study and further close the existing research gaps, the authors of this thesis have formulated three research questions:

RQ 1: What are millennials’ attitudes toward fast fashion?

Fast fashion has become a leading sector within the fashion industry, as it presents a capability of responding to consumers’ continuously changing demand for fashion and new styles (Rocha et al., 2005). However, the increasing consumption of fast fashion has generated a discussion of the issues production causes on the environment (Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010; Kostadinova, 2016). Consequently, consumers have started to grasp the negative impact of consumption, and therefore have become more conscious in their consumer behavior (Perera et al., 2018) and critical toward the producing companies (Wang et al., 2015; Rim et al., 2016). This research question aims to explore millennials’ perception of the fast fashion industry as well as their attitudes toward it. Furthermore, in order to fulfill the purpose of this study and answer the research questions, it is essential to develop an understanding for consumers’ experience with fast fashion.

RQ 2: What are millennials’ attitudes toward sustainability and CSR?

The growing debate regarding sustainability has generated a new demand from consumers, in terms of transparency (Jamil & Mirshak, 2007). As a result, CSR has become a frequently adopted strategy among businesses (Savitz & Weber, 2014). On the one hand, literature suggests that consumers care about whether companies take sustainability into concern or not and engage in CSR activities (Perera et al., 2018; Rim et al., 2016). In contrast, other researchers claim that consumers often express skepticism towards CSR and companies’ ability to actually do good for the environment and society (Bray et al., 2011; Burke et al., 2014). Additionally, millennials are assumedly the most concerned generation when it comes to sustainability and preserving the environment (Farrell, 2019). With this research question, the authors of this paper aim to gain further insight into millennials’ attitudes toward sustainability and CSR, with the new and unique angle of emerging markets. The empirical findings are compared and discussed to what the existing literature claims.

RQ 3: Which factors affect millennials’ decisions when purchasing fast fashion?

In recent years, the traditional four-step procedure of consumers’ decision-making process has become questioned. Literature suggests that consumers’ increasing awareness about sustainability and related issues has generated a more complex process of making purchase decisions (Bray et al., 2011; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). The modern era of research emphasize the role of consumers’ attitudes and how they ultimately impact consumers’ product choices (Papaoikonomou, 2013; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). However, existing literature also highlight a difference between attitude and behavior, suggesting that consumers do not necessarily act in accordance with their attitudes (Morwitz et al., 2007). Previous research has found that specific individual and product characteristics, together with socio-demographic variables, are influencing consumers’ attitudes and behavior (see chapter 2.1.2). However, the aim of this research question is to identify additional factors influencing consumers, and thereby contributing with new insights on how personal values impact buying motives. The three research questions will be answered based on empirical findings from semi-structured interviews. A detailed description of the methodology that has been applied in this thesis is outlined in the following chapter.

3. Methodology

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The following chapter presents details about the methodological elements adopted in this research, and provides a discussion for how and why the chosen elements are considered suitable for this specific thesis. The chapter includes an introduction to the philosophy of interpretivism, in addition to the abductive research approach and qualitative design. Thereafter it discusses how data has been collected, in terms of primary and secondary data. The chapter further explains how we selected our sample and how the interviews were done. Additionally, the research instrument and data analysis are presented. Lastly, quality measurements, in terms of validity and reliability are outlined, as well as the ethical considerations of the research.

______________________________________________________________________

3.1 Research Philosophy

According to Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2016) the research philosophy aims to describe researchers’ beliefs and assumptions about how a study’s data should be gathered, interpreted and used. Generally, researchers make conscious and unconscious assumptions during every step of the research, including assumptions about the realities encountered, human knowledge, as well as how researchers’ own values influence the research process (Saunders et al., 2016). Thus, the selection of research philosophy consequently guides the overall research. Saunders et al. (2016) claim there to be five major philosophies applicable in business research, namely positivism, critical realism, postmodernism, pragmatism, and interpretivism.

The philosophy of positivism emphasizes the importance of producing data and facts that are not influenced by human interpretation or bias (Saunders et al., 2016). Research that adopts positivism is often characterized with a structured quantitative method, where data is collected through observation and translated into measurable statistical data (Saunders et al., 2016). In addition, Saunders et al. (2016) claim that this approach requires the researchers to remain objective without involve any personal

values. Critical realism has been developed as a response to positivism, and focuses on uncovering underlying structures of reality by explaining, which is done by explaining what is seen and experienced (Saunders et al., 2016). The philosophy of critical realism assumes there are two steps of understanding reality. Firstly, by the sensations and events people are experiencing, and secondly, by the way people are mentally processing the aftermath of the experience (Saunders et al., 2016). Similarly to positivism, critical realist’ researchers strive to minimize bias and remain objective, although socio-culture background and previous experiences might influence the research to some extent (Saunders et al., 2016). Moreover, the philosophy of

postmodernism is taking a completely different approach as it emphasizes importance

of values in research (Saunders et al., 2016). The philosophy seeks to question the generally accepted way of thinking and highlight alternative views, which is done by emphasizing the role of language and power relations (Saunders et al., 2016). Similarly, the philosophy of pragmatism is applicable to value-driven research, where researchers are focus on finding practical solutions and outcome (Saunders et al., 2016). Furthermore, reality is of essence in pragmatism research as effects of ideas and knowledge are important elements that enable practical outcome (Saunders et al., 2012). In contrast to the other philosophies, pragmatism research is initiated and sustained by the researchers’ own beliefs and doubts, and is therefore less concerned with objectivity (Saunders et al., 2016).

This research is however adopting the philosophy of interpretivism, which aims to “create new, richer understandings and interpretations of social worlds and contexts” (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 140). The approach emphasizes that different people make different interpretations of experiences based on cultural background, circumstance and time (Saunders et al., 2016). Consequently, this result in a variety of social realities, meaning that there cannot be any universal “laws” or norms that apply to all individuals, which other philosophies suggest (Saunders et al., 2016). Interpretivism is suitable for this research as it aims to uncover consumers’ personal values towards the phenomena of CSR and motivational factors that impact the decision-making process, which requires emphasis on perceptions and interpretations, rather than statistical