What drives Purchase Intent in

E-commerce?

Brand Equity or Product Reviews

Axe Nils

Scherler Hendrik

School of Business, Society & Engineering

Course: Master Thesis in Business Administration

Course code: FOA403

Supervisor: Ulf Andersson

Abstract

Date: June 8, 2020

Level: Master Thesis in Business Administration, 15 cr

Institution: School of Business, Society and Engineering, Mälardalen University

Authors: Nils Axe Hendrik Scherler

(85/09/09) (92/10/20)

Title: What drives Purchase Intent in E-commerce? Brand Equity or Product Reviews

Tutor: Professor Ulf Andersson

Keywords: purchase intent, eWOM, brand equity, online product reviews, e- commerce

Research question To what extent do the utilization of online product reviews and brand equity influence purchase intent in an online setting?

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to investigate the relative effects that brand equity as well as the utilization of online product reviews have on the purchase intent of consumers.

Method: This research was conducted by means of a quantitative study. The data was collected using an online survey. The survey was constructed and distributed in collaboration with a research group at Mälardalen University.

Conclusion: The results suggest that both concepts, brand equity and online product reviews, have a direct influence of the purchase intent of consumers. However, both play an approximately equally important role in online consumer behavior. The utilization of online product reviews has a slightly bigger effect than brand equity on the online purchase intent.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our highest appreciation to our supervisor Professor Ulf Andersson for his guidance and feedback during the research process. Further, we would like to thank Professor Cecilia Lindh for her support during the formulation of the survey, Yi Weifei and Jiaying Zhu for their input during the seminars, Todd Drennan for his support in using SPSS and finally the two other research groups with the common research area.

We would also like to thank all the respondents who took the survey and forwarded to family and friends. This study would not have been possible without your contribution.

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 2 Acknowledgements ... 3 List of Figures ... 6 List of Tables ... 6 1 Introduction ... 71.1 Problem discussion and research area ... 8

1.2 Purpose and Research question ... 8

2 Theoretical background and framework ... 9

2.1 E-commerce ... 9 2.2 Purchase Intent ... 10 2.3 Brands ... 11 2.3.1 Brand equity ... 11 2.3.1.1 Brand awareness ... 12 2.3.1.2 Brand image ... 12

2.4 Online product reviews ... 13

3 Research hypothesis and conceptual model ... 16

3.1 Hypothesis development ... 16

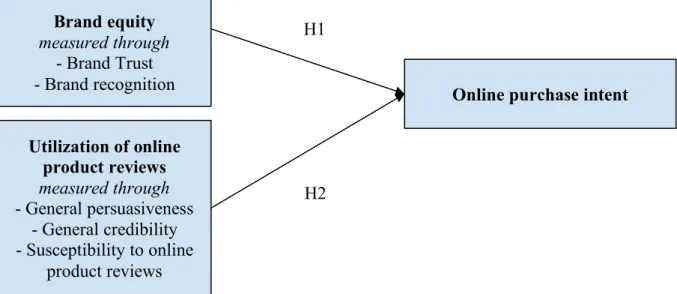

3.2 Conceptual model ... 18

4 Methodology ... 20

4.1 Research philosophy ... 20

4.2 Approach to theory development ... 20

4.3 Methodological choice ... 21

4.4 Strategy ... 21

4.5 Time Horizon ... 22

4.6 Techniques and procedures ... 22

4.6.1 Data collection ... 22 4.6.2 Operationalization ... 23 4.6.2.1 Dependent variable ... 23 4.6.2.2 Independent variables ... 23 4.6.3 Controls ... 25 4.6.4 Reliability ... 25

4.6.5 Validity ... 26 4.6.6 Research ethics ... 26 4.6.7 Data Analytics ... 26 5 Empirical data ... 27 5.1 Data analysis ... 27 5.1.1 Correlations ... 27 5.1.2 Regression ... 29 6 Discussion ... 31 6.1 Controls ... 31 6.2 Brand equity ... 31

6.3 Online product reviews ... 32

6.4 Comparative analysis ... 32

6.5 Cohorts ... 32

7 Conclusion ... 33

7.1 Managerial Implications ... 33

7.2 Limitations ... 34

7.3 Suggestions for future research ... 34

References ... 36

List of Figures

FIGURE 1:CONCEPTUAL MODEL ... 18

FIGURE 2:CONCEPTUALIZATION BRAND EQUITY ... 24

FIGURE 3:CONCEPTUALIZATION ONLINE PRODUCT REVIEWS ... 25

List of Tables

TABLE 1:SPEARMAN CORRELATION ... 28

1 Introduction

The internet has had an impact on virtually all areas of society including the way to do business. Since the emergence of e-commerce, the meaning of the term and its role in the business world has changed many times. In the beginning, e-commerce was considered to be support for business processes, later a strategic tool for organizations and nowadays it has become a part of our daily lives (Mohapatra, 2013, p. 3). With the proliferation of internet access and rising consumer acceptance within the past 20 years, e-commerce has globally been growing steadily at 20+% rates and accounted for 3,535 Billion USD in 2019 or 14.1% of all retail (eMarketer, 2019).

Since online retail uses digital processes and web interfaces, the way in which information is conveyed differs largely from traditional offline retail (Jiang & Benbasat, 2004). Using web interfaces prevent consumers from experiencing a product firsthand, hence purchasing goods online involves additional risk for the consumer. This product-risk originates from the difference in expectation of and the actual product characteristics (Jiang & Benbasat, 2004) and results in a higher perceived risk for consumers regarding online purchases (Tan, 1999). This has a subsequent effect on their purchasing behavior (Jarvenpaa, Tractinsky, & Vitale, 2000). To mitigate this risk of online retail, many strategies have been conceived by marketers like e.g. product trials (Jiang & Benbasat, 2004) or more generally the building of brand trust (Hahn & Kim, 2008). As a result of risk mitigating practices by consumers, both brands (Luo, 2002; Hahn & Kim, 2008) and product reviews (Schindler & Bickart, 2005; Sen & Lerman, 2007) become central concepts influencing consumer behavior. These characteristics have numerous implications for online marketing. Hence, understanding the relationship of those concepts and their respective influence on consumer behavior is important to both marketing managers and scholars. Prior research has considered both brands (Gefen & Straub, 2004; Jarvenpaa, et al. ,2003) as well as online product reviews (Zhang & Tran, 2009) as important ways for consumers to form their purchase intent. Marketers have used these insights and suggested tools for market cultivation such as brand communities (Laroche, Habibi, Richard, & Sankaranarayanan, 2012) and review systems (Zhu & Zhang, 2010).

Another important way for consumers to form purchase decisions is electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) or more specifically online product reviews (Zhang & Tran, 2009). Traditional WOM (word-of-mouth) is consumer-to-consumer communication about a product and has been identified as an important influence on consumer behavior (Chatterjee, 2001; Sen & Lerman, 2007). The new technologies of the internet enhance these consumer communications by

turning one-to-one communication into one-to-many. This increases the accessibility and the reach considerably and subsequently raises the effectiveness of eWOM (Chatterjee, 2001).

1.1 Problem discussion and research area

Apart from Bambauer-Sachse & Mangold (2011), no research has been done on the interaction of brands and online product reviews and their relationships.

Brands and the brand relationships with the customer have been a part of marketing for a long time and has since become a popular field of research. Particularly brand equity, often defined as the additional value of a product originating from the respective brand, has been the subject of studies, papers and books with the most influential work being done by Aaker (1991) and Keller (2008).

Furthermore, WOM is considered to be more influential on consumer behavior than advertisements or editorial recommendations (Bickart & Schindler, 2001; Smith, Menon, & Sivakumar, 2005) and consumers use of WOM is increasing over time (Zhu & Zhang, 2010). Hence, the way ahead will likely challenge traditional views of marketing and consumer purchase behavior.

With further expansion of internet usage and subsequently the reach of eWOM it seems conceivable that at least for some consumers the concept of brands and brand-trust as a conventional form of outbound marketing is crowded out by an increasing importance of the inbound marketing of user generated product reviews.

1.2 Purpose and Research question

This study explores the relative effects that brand equity as well as online product reviews have on the purchase intent of consumers.

Both brand equity and product reviews can be seen as a way of mitigating perceived risk for the customer (Erdem & Swait, 2001; Yang, Sarathy, & Lee, 2016). However, the question remains if this is this applicable in an online setting, which mechanism is more effective, and what are the interrelated effects. Hence, the research question is as follows:

To what extent do the utilization of online product reviews and brand equity influence purchase intent in an online setting?

2 Theoretical background and framework

2.1 E-commerceThere are numerous ways to define the term “e-commerce”. An abbreviation of “electronic commerce” (Mohapatra, 2013, p. 8), it can refer in the broadest sense to the use of the Internet and other networks, such as Intranets to purchase, sell, transport or trade data, goods or services (Turban, Whiteside, King, & Outland, 2017). The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines e-commerce as an “electronic transaction, which is the sale or purchase of goods or services conducted over computer networks” (OECD, 2013) and the World Trade Organization as the “production, distribution, marketing, sales or delivery of goods and services by electronic means” (WTO, n.d.). Moreover, e-commerce can be seen as a subset of e-business, which refers not only to the buying and selling process, but all kinds of businesses such as servicing customers, collaborating with business partners, as well as delivering electronic transactions (Turban, et al., 2018, p. 7). Within the scope of this study we define e-commerce to be the marketing and sales of goods and services by the means of the Internet.

The US Department of Commerce states several advantages for customers using e-commerce. It provides access to a global marketplace connecting supply and demand from around the world. Customers have access to products, services and information at any time of day or night from any location making it very convenient. The speed of shopping is faster than traditional retail and more transparent since it is easier to compare prices and discount for equal products. Additionally, e-commerce offers an interactive opportunity to learn more about products and how to use them (Commerce, 2020).

This research project focuses on the influence of brand equity and online product reviews on the purchase intent of consumers, subsequently highlighting the Business-to-Consumer relationship or the consumer market. Kotler, et al. (2005, p. 255) define the consumer market as all individuals and households acquiring goods and services for personal consumption. Understanding the behavior that individuals and households have in the marketplace is the purpose of consumer behavior models. They aim to help companies understand how a consumer forms a purchase decision (Turban, King, Viehland, & Lee, 2006, p. 140). Characteristics affecting consumer behavior are cultural-, social-, personal- and psychological factors. Research has shown that older users do not use e-commerce as often as younger users in order to make purchases (Mitzner, et al., 2010). This might be related to the perceived risk of online shopping since studies have identified older people as being more risk-averse than younger

female shoppers are more averse than male shoppers and low income groups are less risk-seeking than middle or high income groups (Sharma & Kurien, 2017).

2.2 Purchase Intent

Purchase intent is the decision of a customer to buy a product or service. However, there are many different definitions of the actual characteristics and influences of purchase intent. It constitutes the penultimate step in the decision-making process before the customer actually buys the product. To reach this step the consumer passes several stages until they manifest purchase intent or in the case of most studies the outward supportive communication (Kim, Park, & Kim, 2017). These stages include need identification and problem awareness, information gathering, evaluation of alternative solutions (products), selection of an appropriate solution (product) and the post-purchase evaluation of decision (Jobber & Lancaster, 2015, p. 81). During this process there are many different factors affecting the purchase intent such as brand relationships (Anuwichanont & Rajabhat, 2011), eWOM (Lee, Lee, & Shin, 2011) or the customers general personality (Till & Busler, 2000).

The factors important in the forming of purchase intent and their relative effects are a source of debate among scholars. East, Hammond and Lomax (2008) conducted a study indicating that negative electronic word-of-mouth has twice as much influence on the purchase intent of customers than positive electronic word-of-mouth. However, Bredahl (2001) identified brand attitude as the most important determinant of the purchase intent. Dick and Basu (1994) proposed that a consumer´s purchase intent increases when the consumer is positively affected by a brand due to an emotional connection (1994). Another factor is perceived risk. Park, Lennon and Stoel (2005) stated that a lower perceived risk might be related to a higher purchase intent. This finding is confirmed by Vijayasarathy and Jones (2000), who propose that the perceived risk is an important factor for consumers when buying online.

Furthermore, purchase intent depends on the value obtained by the customer in previous transactions, such as benefits, competition and costs. More simply put future purchase intent is related with customer satisfaction (Olaru, Purchase, & Peterson, 2008). Previous research has shown that companies need to strive for customer satisfaction and to remedy customer dissatisfaction, since satisfaction is assumed to lead to brand loyalty and repeat sales (Blodgett, Granbois, & Walters, 1993). This further suggests a connection exists between purchase intent as well as eWOM since responding to service failures and complaints openly creates more loyal customers, whereas complainants who perceive a lack of justice are more likely to engage in negative word of mouth (Maxham, 1999).

2.3 Brands

Brands are complex concepts, fulfilling many functions both within society and of course the economy. At its core a brand is a way of differentiating an offering from those of competitors which is illustrated by numerous similar definitions in literature e.g. American Marketing Association (Aaker, 1991; Kotler & Keller, 2009). The nature of this differentiation is very specific to the brand, ranging from functional to symbolic, rational to emotional or tangible to intangible. (Kotler & Keller, 2009). The ability to set themselves apart from the competition and endow offerings with information enables companies or other organizations to form a (brand-) identity (Balmer, 2010).

This establishment of identity performs numerous valuable functions for companies in the modern marketplace adding value to the offering that transcends mere sales promotion or advertising (Aaker, 1991). This becomes more important in an international setting and more recently in e-commerce (González-Benito, Martos-Partal, & San Martín, 2015; Erdoğmuş, Bodur, & Yilmaz, 2010).

Customers also benefit from brands explicitly as well as implicitly. While a brand can increase the value of the offering itself (Li, Li, & Kambele, 2012) it facilitates decision-making by saving time (Suri & Monroe, 2003) and reducing risk (Matzler, Grabner-Kräuter, & Bidmon, 2008). The latter is growing in significance with the advent of e-commerce (Hahn & Kim, 2008) through alleviating uncertainty about product attributes (Erdem, Swait, & Louviere, 2002). However, the underlying concept of brand added value arguably remains the same as thirty years ago, namely brand equity.

2.3.1 Brand equity

Many different approaches to brand equity exist. The most prominent ones are the financial perspective (Simon & Sullivan, 1993) the asset perspective (Aaker, 1991) and the customer-based perspective (Keller, 2008). Whereas the financial perspective concerns mainly accounting and valuation issues, the asset perspective offers an aggregate view of the assets that underlie brand equity, adding value to both the firm and the customer (Aaker, 1991) However, arguing that the source of the value of brand equity for firms is largely caused by the relationship between the customer and the brand, the customer-based perspective focuses on the “differential effect, that brand knowledge has on consumer response to the marketing of that brand” (Aaker, 1991).

Building on the associative network memory model Keller proposes two aspects to create brand equity: Brand awareness - having awareness and familiarity with the brand - and brand image - holding strong, favorable and unique brand associations. (Keller, 2008).

2.3.1.1 Brand awareness

Brand awareness can be operationalized through brand recognition, which is the “ability to confirm prior exposure to the brand when given the brand as a clue” (Keller, 2008) and brand recall which is the “ability to retrieve the brand from memory when given a product category, the needs fulfilled by the category, or a purchase or usage situation as a clue” (Keller, 2008). Further studies on brand familiarity propose it is a relevant determinant in a customer forming his purchase intent both in an offline (Laroche, Kim, & Zhou, 1996) and online setting (Park & Stoel, 2005; Laroche, et al., 2012). The reasons behind this are in part the inherent risk of online retail (Jarvenpaa, et al., 2000). Namely, the transactional risk of security and privacy within the e-commerce process (Keeney, 1999; Dinev & Hart, 2006) as well as the uncertainty about the product expectations (Keeney, 1999; Erdem, et al., 2002) due to the intangibility in the purchasing process (González-Benito, et al., 2015).

While the transactional risk is addressed by the online retailer or e-commerce platform (Yoon, 2002), the intangibility risk can be addressed on a product level by exploiting effects of brand extension i.e. that corporate brands can transfer a positive effect on products (Aaker, 1991; Keller, 2008).

2.3.1.2 Brand image

Brand image as the relationship a customer forms with a brand over time is “reflected by the brand associations held in consumer memory” (Keller, 2008). These associations are mostly brand specific and include both product characteristics as well as more abstract, non-product views. The operationalization of the brand image in the customers memory can be made through brand attributes and brand benefits (Keller, 2008). Brand attributes represent the characterizing features of a product or service whereas brand benefits involve the meaning and value that the customer attributes to the product or service (Keller, 2008). The beliefs about the attributes and benefits can be formed in a variety of ways such as “nonpartisan sources such as Consumer Reports or other media vehicles; word of mouth; and any assumptions made about the brand itself e.g. its name, logo, identification with the company, country, channel of distribution, or person, place or event.” (Keller, 2008).

While the source of the belief is less important the “strength, favorability, and uniqueness” of those associations are most important (Keller, 2008). As such, attitudinal aspects of brand behavior like brand trust as a consequence of a positive brand image becomes an important

concept. Essentially trust can be defined as “a trustor’s expectations about the motives and behaviors of a trustee” (Jarvenpaa, et al., 2000) or in other words a customer’s expectation that a brand will deliver on its promises (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995). In an online setting, brand trust lowers the customers uncertainty about the product and in effect relieves that product risk (Tan, 1999).

2.4 Online product reviews

Traditional WOM has been explored as an interpersonal exchange of information due to consumers social relations (Brown & Reingen, 1987). By some researchers it is considered to be a strong and credible influence on consumer behavior (Gupta & Harris, 2010). Due to the development of the internet and the subsequent growth of e-commerce the more recent concept of eWOM has attracted great attention from scholars and researchers alike (Chan & Ngai, 2011). The rise of new technologies enables consumers to easily share product- and brand-related information with each other reaching a greater audience than traditional WOM (López & Sicilia, 2013). Liu, Hu, and Xu (2017) formalized the main aspects in how eWOM differs from the traditional word-of-mouth:

1. Scope of communication

2. Collection of more reviews in a shorter time 3. Reviews can be measured

As such, eWOM can be considered as an extension of interpersonal communications severely increasing the scope or reach of the individual review (Chan & Ngai, 2011). In practice, distinct review websites (but also online retailers) collect and grant access to a great number of reviews, giving eWOM a higher salience and enhancing its impact compared to traditional word-of-mouth. Finally, online product reviews are often quantifiable as many platforms offer rating systems, making them easily measurable and comparable (Liu, et al., 2017).

When looking at the provider of eWOM platforms the marketer-generated platforms can be differentiated from the non-marketer-generated platforms (Lee & Youn, 2015) however, combinations exist. This distinction also has relevance when considering the creator of the review. Traditionally it is recognized as a form of user-generated content. Often the content of eWOM is online product reviews posted by anonymous consumers (Liu, et al., 2017). Unlike information provided by marketers it offers information about products or services and the user experiences, which are rarely available from manufacturer-controlled sources (Reichelt, Sievert, & Jakob, 2013). Liu et al. (2017) state that consumer online reviews consequently play an important role in the decision-making process of consumers (2017).

Previous studies found out that eWOM influences the purchase intent of consumers in different ways such as an increased time spent on online product search (Gupta & Harris, 2010). Other eWOM influences are an increase of online sales (Zhu & Zhang, 2010), consumer attention (Daugherty & Hoffmann, 2014), new product adaptions (López & Sicilia, 2013), perceived product quality (Koh, Hu, & Clemons, 2010) and choice of products (Huang, Hsiao, & Chen, 2012). Liu et al. (2017) state that consumer online reviews consequently play an important role in the decision-making process of consumers (2017).

In practice marketers often use brand communities to try to monitor and positively influence eWOM content (Reichelt, et al., 2013). Many of the largest online retailers such as Office Depot, Amazon or Home Depot encourage eWOM by allowing online reviews on the products they offer (Gupta & Harris, 2010). Additionally, traditional social media networks such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTubes support user-generated communication (Schivinski & Dabrowski, 2016).

Liu et al. (2017) identify credibility as an important aspect concerning the nature and effectiveness of eWOM. Consumers often doubt the credibility of eWOM if it is mostly positive (Reichelt, et al., 2013). But also the origin of the review is important as Tsao and Hsieh (2015) suggest, positive and high-quality eWOM increases the credibility when the origins are independent review platforms. This resulted in a positive impact on the purchase intent of the consumer (Tsao & Hsieh, 2015). That independence of online product reviews being an important factor is also shown by Godes and Mayzlin (2009), who propose that the impact of eWOM from an unknown user is greater in comparison to company communication, which is created from a company (Godes & Mayzlin, 2009).

But of course, the content of the reviews matters too. Previous studies show that there is a correlation between negative reviews and the evaluation of a retailer. A negative review influences the purchase intention to this respective retailer negatively (Chatterjee, 2001). The results of the study by Chevalier and Mayzlin (2006) support the notion that reviews have an impact on the purchase intention of a consumer. However, the perceived trustworthiness and usefulness of the reviews influence the impact the eWOM has on the customer (Xia & Bechwati, 2008).

Comparing gender and age preferences regarding eWOM is source of debate among scholars. Male consumers seem to be using eWOM more than female users (Karabulut & Bulut, 2016). Furthermore, the ratio of negative eWOM is higher for males, whereas positive eWOM is more common for females. Generally, females attribute a higher credibility to eWOM than males indicating the effect being higher on females than males (Karabulut & Bulut, 2016). However,

other studies state males give more importance to eWOM, so no general assumption can be made at this point (Rondan Cataluña, Arenas Gaitán, & Ramirez Correa, 2014).

Regarding the age structure in eWOM usage there seem to be differences when comparing generation X and Y. A study by Karabulut and Bulut (2016) proposes that eWOM messages are more effective for generation Y than generation X. Another study suggests that older consumers prefer face-to-face and telephone conversations, whereas younger people are more affine towards digital messages (Iyer, Yazdanparast, & Strutton, 2017).

3 Research hypothesis and conceptual model

As presented above, online retail differs from traditional retail in various ways. A consequential one is the impossibility for the customer to scrutinize the product before the purchase leading to uncertainty concerning the properties of the product (Jarvenpaa, et al., 2000). This leads to the associated risk for the customer or more precisely the risk of the product not living up to expectations (Keeney, 1999; Erdem, et al., 2002) resulting in a higher price sensitivity (Erdem, et al., 2002) and arguably in lower purchase intent.

Since this is a central issue of online retail, researchers have studied means to mitigate these risks. Prior research suggests that both brand equity (Cobb-Walgren, Ruble, & Donthu, 1995) as well as online product reviews might work in mitigating this product or quality risk (Wu, Wu, Sun, & Yang, 2013).

Subsequently, this study proposes that having greater brand equity will likely result in a higher purchase intent of the customer. At the same time the utilization of online product reviews is considered to influence the purchase intent positively. In order to understand the effects and interrelation of those concepts, we try to differentiate and investigate them according to previous studies and conceptualizations.

3.1 Hypothesis development

As previously mentioned Keller (2008) defines brand equity as the result of brand knowledge and the respective effect of the marketing activities it has on customer behavior. Earlier research suggests that brand equity has an effect on the consumer preferences and purchase intent of customers (Cobb-Walgren, et al., 1995). When looking at the elements of brand equity proposed by (Keller, 2008), namely brand awareness and brand image, we discover that those individually are important considerations for forming consumer behavior.

Brand awareness has been identified as an important aspect of forming purchase intent in an online setting (Park & Stoel, 2005; Laroche, et al., 2012). Again, it can be assumed this is a consequence of reducing the perceived risk of the customer (Rubio, Oubiña, & Villaseñor, 2014). Brand image also has been found to influence purchase intent (Jalilvand & Samiei, 2012; Torlak, Ozkara, Tiltay, Cengiz, & Dulger, 2014). Within this study we conceptualize brand trust as a result of a positive brand image and subsequently higher brand equity. Brand trust is the belief of a customer that the customer can “rely on the ability of the brand to perform its stated function” (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). Prior research suggests that brand trust positively affects market share and relative price (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001) so it seems

likely that it influences the customers online purchase intent. Furthermore, this is a way to mitigate the perceived risks associated with e-commerce (Matzler, et al., 2008)

Conceptually the research by Cobb-Walgren, et. al (1995) already opens up questions about the operationalization of brand equity persisting in the academic discourse until today. However, Feldwick (1996) points out that brand equity is necessarily a vague concept because concentration of a certain set of measures might exclude other important aspects of the question. Adhering to that spirit we broadly follow the reasoning of Keller (2008), however adjusting our conceptualization of brand equity as follows:

First, we use brand recognition as an indicator for brand awareness (Keller, 2008) and second we are using brand trust as a benchmark for positive brand image. Delgado-Ballester and Munuera-Alemán (2005) propose an inclusion of brand trust as the result of prior experiences with a brand to more accurately describe brand equity. Following the reasoning of Esch, Langner, Schmitt and Geus (2006) purchase intent is not directly influenced by brand image but rather via brand relationships such as brand trust, our construct includes both brand recognition and brand trust for the compound variable of brand equity. This way we measure central concepts of brand building, the experiential (trust) and the informational (recognition) and their respective effect on online consumer behavior.

In conclusion we hypothesize that through the compound variable brand equity, measured by combining both brand trust and brand recognition, positively affects online purchase intent: H1: There is a positive relationship between brand equity (brand trust and brand recognition) and online purchase intention

Furthermore, customers are influenced by other people when forming their decisions (Park & Lessig, 1977). As a result, traditional word of mouth has long been accepted as a robust influence on purchase behavior of customers (Gupta & Harris, 2010). The proliferation of the internet has on the one hand enabled customers to easily generate access word of mouth messages with a distinctly higher reach (López & Sicilia, 2013) and on the other created a need for reducing uncertainties inherent in the e-commerce process (Jarvenpaa, et al., 2000).

Huang and Chen (2006) suggest that eWOM offers cues for customers that influence purchase intent. I.e. a positive word of mouth is likely to have a positive effect on potential customers, however negative word of mouth is likely to have a (higher) negative effect.

This is further examined by Yang, et al. (2016) suggesting, that online product reviews affect the perceived risk of customers and in turn the purchase intent. A negatively reviewed product communicates a higher (product-)risk to the customer and in turn has a greater negative effect

on the purchase intent than balanced or positive reviews have. This suggests the perceived risk being the relevant mechanic influencing consumer behavior.

Subsequently we hypothesize that the utilization of eWOM in form of online product reviews lowers the uncertainty of the customer and in turn positively affect online purchase intent: H2: There is a positive relationship between the utilization to online user reviews and online purchase intent

Brand equity has its origin in the prior experience of a customer with the brand over time (Keller, 2008). This includes both experiences with the brands products or services as well as marketing programs injecting brands with meaning.

Since eWOM is a consumer-controlled source of information it offers valuable and manufacturer-independent information for the customer about the product (Reichelt, et al., 2013). This makes eWOM a credible source of information about the product and the brand prior to the purchase (Liu, et al., 2017).

Furthermore, we will explore if eWOM in the form of online product reviews work in raising brand awareness and shape a customer’s opinion about a brand affecting the brand equity prior to own experience.

3.2 Conceptual model

Hence, the conceptual model is conceived as follows:

Figure 1: Conceptual model

H2 H1 Utilization of online product reviews measured through - General persuasiveness - General credibility - Susceptibility to online product reviews Brand equity measured through - Brand Trust

The variables brand trust and brand recognition are combined into the composite variable brand equity. Together with online user reviews both represent the independent variables of the model influencing the dependent variable of purchase intent.

Furthermore, a secondary influence of online user reviews on brand equity was examined by investigating possible correlations.

4 Methodology

This section discusses the methods used to answer the research question as stated in the introduction of the paper and explains the chosen research design. As a methodological framework we use the research onion developed by Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill (2016) to determine a systematic and applicable framework for data collection, insights and analysis. Therefore, all layers from the outside to the inside are discussed in the following.

The six layers consist of 1) research philosophy; 2) approach to theory development; 3) methodological choice; 4) strategy; 5) time horizon; 6) techniques and procedures (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 124)

4.1 Research philosophy

The research philosophy is “a system of beliefs and assumptions about the development of knowledge” (Saunders, et al., p. 124). Based on the objective to identify to what extent brand equity or online product reviews influence the online purchase intent, positivism with its respective assumptions of axiology, epistemology and ontology was most suitable. Positivism “focuses on strictly scientific empiricist methods to yield pure data and facts uninfluenced by human interpretation or bias” (Saunders, et al., 2016). The researcher is detached, neutral and independent as this research philosophy aims to be as neutral as possible and avoids any influences on findings in order to be value-free (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 136; Blumberg, Cooper, & Schindler, 2011, p. 17). Positivists focus on measurable and quantifiable data (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 137) and following the assumptions that the social world is observed by objective facts and consists of simple elements to which it can be reduced (Blumberg, et al., 2011, p. 17). As this study aims to produce law-like generalizations by using a survey with a large sample size, this research philosophy was used as a framework throughout the entire duration of this research project.

Other research philosophies such as interpretivism or postmodernism were not applicable for this project. Interpretivism concentrates on studying meanings (Saunders, et al, 2016, p. 140), whereas postmodernism focuses on the role of language and power relations (Saunders, et al, 2016, p. 135).

4.2 Approach to theory development

The next layer of the research onion discusses approaches of the theory development. Saunders, et al. (2016, p. 145) present three different approaches: 1) deductive; 2) inductive; 3) abductive.

A deductive approach “starts with theory, often developed from reading of academic literature, and designing a research strategy to test the theory” (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 145). An inductive approach starts “by collecting data to explore a phenomenon used generate or build theory” (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 145). The abductive approach combines the two previously mentioned approaches. It starts by collecting data “to explore a phenomenon, identify themes and explain patterns, to generate a new or modify an existing theory, which then is tested through additional data collection” (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 145).

The philosophy of positivism is usually connected with a deductive approach. Therefore, a deductive approach in which theory is derived from academic sources and then tested through primary data collected, was followed.

4.3 Methodological choice

Upon the research philosophy and approach, the methodological framework distinguishes between three methods: 1) qualitative; 2) quantitative; 3) mixed-methods. Qualitative data uses non-numerical data by the use of interviews or categorizing data (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 165). On contrary, quantitative data uses data collection methods that generate or produce numerical data (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 165). Quantitative research is often associated with the positivism research philosophy and a deductive approach to theory development (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 166).

For this research project, quantitative data was collected using a survey. Therefore, a mono-quantitative study has been used.

4.4 Strategy

The next layer of the research onion discusses the research strategy. Saunders, et al. (2016, p. 177) propose eight different research strategies: 1) Experiment; 2) Survey; 3) Archival and documentary research; 4) Case study; 5) Ethnography; 6) Action research; 7) Grounded theory; 8) Narrative Inquiry. The choice of research strategies was guided by the coherence with the positivism philosophy as well as the research approach and purpose. The correct choice enables the researcher to answer the research question and establishes coherence within the project. Related to a quantitative approach are the first four mentioned strategies, whereas archival and documentary research as well as case study can be used in either qualitative or quantitative approach (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 178).

As part of the survey strategy, a questionnaire was used in order to ensure a standardized collection of data from a sizable sample. The use of a questionnaire allowed the researcher to in control of the research process and collect quantifiable findings.

4.5 Time Horizon

Regarding the time horizon, it can be distinguished between a cross-sectional and a longitudinal study. A cross-sectional study involves investigating a specific phenomenon at a particular time, whereas a longitudinal study focuses more on the investigation on change and development (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 200). Due to the research objective and the given timeframe of twelve weeks, a cross-sectional study was suitable for this research project.

4.6 Techniques and procedures

The last layer of the applied research onion discusses techniques and procedures that have been used during the research process.

4.6.1 Data collection

The aim of this study is to investigate to what extent online product reviews and brand equity influence the purchase intent of consumers in an online setting. As part of the survey strategy, a self-completed questionnaire has been used to collect valuable data online.

The data was collected through an online survey for their low cost, ability to reach a large sample size, greater speed of data collection and an automated data input (Blumberg, et al., 2011, p. 168). The questionnaire was based on existing literature (see Appendix A) and was accessible through the online survey tool SUNET. The questionnaire is a combined effort of 7 researchers forming 3 respective research groups at Mälardalen University Sweden. Each group used their own conceptual model and hypotheses related to online consumer behavior. Not all question items asked in the survey have been used for this study since each group had specific questions related to their respective conceptual model and hypothesis.

Demographic information such as age, gender, nationality and education were part of the questionnaire to control for these variables. Other questions were used in order to measure pre-defined concepts. These concepts are validated in prior research such as “online purchase intent” (Anastasiadou, Lindh, & Vasse, 2019), “brand equity” (Keller, 2008) and “consumer generated reviews” (Bambauer-Sachse & Mangold, 2011) whereas the contents of brand equity are adjusted to the needs of this specific research.in accordance with e.g. Bambauer-Sachse and Mangold (2011).

Prior to publishing the survey, the questionnaire was assessed in a pilot test. The main goals were to measure the average completion time, assessing the understanding, and testing its overall functionality.

Convenience sampling was used for gathering the data. It is commonly used in quantitative research in order to collect large data sets (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 303; Blumberg, et al., 2011, p. 194). It must be stated that this technique is limited by determining the respondent’s credibility accurately (Johnstone & Lindh, 2018). In order to counteract these issues, specific criteria were used to increase credibility of the respondents. Those criteria were previous experience with online shopping as well as priming the respondents with questions about a recent online purchase and stating the value of said purchase. Further, snowball sampling was used asking respondents to motivate other respondents for the study (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 303). Other sampling techniques were not applicable since it is prone to be biased and influenced as well as it is often given little credibility (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 304).

Potential respondents were addressed through a variety of social media platforms and applications such as LinkedIn, Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram and email. Since the survey was in English, the respondent was required to be able to speak the language.

4.6.2 Operationalization

As mentioned above, this paper uses concepts that have been discussed in the respective literature. However, as mentioned before in the case of brand equity an individual concept has been developed according to the requirements of this study.

Furthermore, the questions used in the survey are all validated constructs from prior research to ensure the necessary efficacy of measuring the right thing. The complete questionnaire is stated in Appendix A.

4.6.2.1 Dependent variable

The dependent variable online purchase intent was measured using a validated concept by Anastasiadou, et al. (2019). It explores the likelihood of further online purchases by the respondent. The compound variable is constructed by 3 Elements, with a Spearman Correlation Coefficient of respectively 0.548**; 0.562**; 0.515** and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.772.

4.6.2.2 Independent variables 4.6.2.2.1 Brand equity

The brand equity construct is adapted from Keller (2008). However, in accordance to Feldwick (1996) and (Delgado‐Ballester & Munuera‐Alemán, 2005) as well as (Esch, Langner, Schmitt,

and a separate construct for brand awareness is used. This way the resulting compound variable brand equity incorporates both experiential aspects of brands (i.e. brand trust) as well as the familiarity (i.e. brand awareness) with the respective brand. Both are central aspects of brand building activities and by measuring those the potential brand equity has on online consumer behavior can be measured accordingly.

Hence, in order to measure the brand equity influencing the online purchase intent, the respondents were asked to specify a recent purchase online and state brief information about the purchased product as to prime the participant for the following questions concerning brand equity.

Brand trust is measured with 4 Elements proposed by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001). The elements have Spearman Correlation Coefficients of respectively 0.775**; 0.758** and 0.721** as well as a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.918.

Brand recognition is measured according to Aaker (1996) (Aaker calling it brand awareness, however in Keller’s view it is more like his concept of brand recognition) and includes 2 Elements with a Spearman Correlation Coefficient of 0.655** and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.772.

The resulting compound variable of brand equity includes both aforementioned constructs in equal shares.

Figure 2: Conceptualization Brand Equity

These 2 elements have a Spearman Correlation Coefficient of 0.684** and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.806.

4.6.2.2.2 Utilization of online product reviews

The second independent variable is a construct proposed by Bambauer-Sachse and Mangold (2011). It is compounded of three individual constructs together reflecting the use and perception of online reviews by consumers.

Brand trust Brand recognition

General persuasiveness of online product reviews is measured with 2 elements yielding a Spearman Correlation Coefficient of 0.646** and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.778.

General credibility of online product reviews is also measured with 2 elements having a Spearman Correlation Coefficient of 0.724** and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.843.

The Susceptibility to online product reviews is again measured with 2 elements with a Spearman Correlation Coefficient of 0.712** and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.829.

Subsequently these three constructs are combined into the compound variable Utilization of online product reviews.

Figure 3: Conceptualization Online Product Reviews

The 3 elements have a Spearman Correlation Coefficient of respectively 0.619**; 0.664** and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.849.

4.6.3 Controls

The survey included controls for other factors influencing online purchase intent such as age, gender, education and the purchase value. All questions include an option to not specify an answer. The age was grouped into seven ranges. Gender included male, female and non-binary. Education was specified as the highest level of completed education and purchase value was given individually as a discrete value but later converted into values above and below 51€, the median value as to get an idea of the nature of the purchase decision being high or low value.

4.6.4 Reliability

Reliability refers to the term whether results are consistent and similar observations would be made by other researchers (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 726; Blumberg, et al., 2011, p. 350). The collection of primary research was conducted at neutral times and through a web-based survey so that participant errors or bias could be minimized. Research errors were reduced through preparations of the survey questions based on prior literature. As Saunders, et al. (2016, p. 451) propose, the primary data was treated objectively to reduce research bias.

General credibility General persuasiveness

Utilization of online product reviews

Susceptibility to online product reviews

In order to measure the consistency of responses of the survey participants as previously stated the Cronbach’s Alpha was used. Cronbach´s Alpha coefficients can have a value between 0 and +1, whereas a value of +1 represents a positive and a value of 0 represents a negative correlation. An alpha greater or equal 0.7 provides a good scale (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 451). All concepts yield a Cronbach’s Alpha of higher than 0.7 indicating sufficient reliability.

4.6.5 Validity

Validity refers to the appropriateness of the measures used, the accuracy of results and generalizability of findings (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 202). Internal validity provides a causal relationship between two variables. External validity concerns whether findings are generalizable and applicable also for other research group and settings. Further, it needs to be taken into consideration that an invalid study affects future studies negatively and reduces their validity (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 203 f.). Triangulation has been used in order to ensure validity. Triangulation refers to the use of more than one data source or method of data collection. By applying triangulation, validity, credibility and authenticity of research findings are ensured (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 207). Triangulation has been applied by using multiple sources such as peer-reviewed articles, research books and governmental reports. Further, primary data has been collected through an online survey. The questions are proven concepts and were used from previous studies (Appendix A).

4.6.6 Research ethics

Ethics refer to moral principles and standards of behavior (Blumberg, et al., 2011, p. 114). The researcher worked with objectivity and integrity to ensure high quality of the research. References are marked with the respective source in order to avoid plagiarism. Survey participants have been provided with sufficient information about the topic and objective of the research. The data outcome of the survey was entered accordingly to ensure correctness of findings and the quality of the output. Access to previous research was gained legally.

4.6.7 Data Analytics

Raw quantitative data has very little meaning before it is processed and analyzed. Therefore, it is necessary to process this data and turn it into information (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 496). After the survey was closed on the 15th of April 2020, quantitative data analysis was applied by

using the program SPSS. Relationships were assessed using Spearman correlations. The reliability of specific concepts is tested with Cronbach´s alpha. A linear regression analysis tested relationships between different variables.

5 Empirical data

The following segment exhibits the results of the survey carried out within this research. This includes the reliability and correlation of the respective constructs of the conceptual model as well as the linear regression analysis concerning the hypotheses presented above including the respective controls.

5.1 Data analysis

There were overall 475 responses to the survey. However, due to many missing cases only 200 responses are included in the relevant dataset. The countries with the most respondents were Finland (23,4%), Germany (22,3%), and Sweden (19,8%). Most of the respondents were between 21 and 30 years old (74%), and the gender distribution of was 69,% females to 30,5% males. The most common education level was a bachelor’s degree (62%) followed the master’s degree (33%).

5.1.1 Correlations

The relationship between the concepts and controls is measured with Spearman’s rho since the data represents ordinal variables (Saunders, et al., 2016, p. 534).

The relationship between age and education is naturally positively correlated. Within this dataset gender is also correlated with education indicating males being higher educated. The value of the purchase is positively correlated with gender, education and brand equity while the utilization of online product reviews is negatively correlated with age. The dependent variable Purchase Intent correlates with both indirect variables Brand equity and Utilization of online product reviews, but with none of the controls.

Age Gender Educ. Purchase value Util. of OPR Brand Equity Purchase Intent Age Correlation Coefficient 1.000 Sig. (2-tailed) . Gender Correlation Coefficient 0.072 1.000 Sig. (2-tailed) 0.311 . Education Correlation Coefficient 0.311** 0.157* 1.000 Sig. (2-tailed) 0.000 0.026 . Purchase value Correlation Coefficient -0.023 0.201** 0.179* 1.000 Sig. (2-tailed) 0.750 0.004 0.011 . Utilization of OPR Correlation Coefficient -0.211** 0.023 0.000 -0.079 1.000 Sig. (2-tailed) 0.003 0.751 0.999 0.265 . Brand Equity Correlation Coefficient 0.112 0.095 0.123 0.209** 0.084 1.000 Sig. (2-tailed) 0.115 0.182 0.083 0.003 0.236 . Purchase Intent Correlation Coefficient -0.021 0.001 0.034 0.046 0.311* * 0.320* * 1.000 Sig. (2-tailed) 0.763 0.990 0.636 0.514 0.000 0.000 .

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). c. Listwise N = 200

5.1.2 Regression

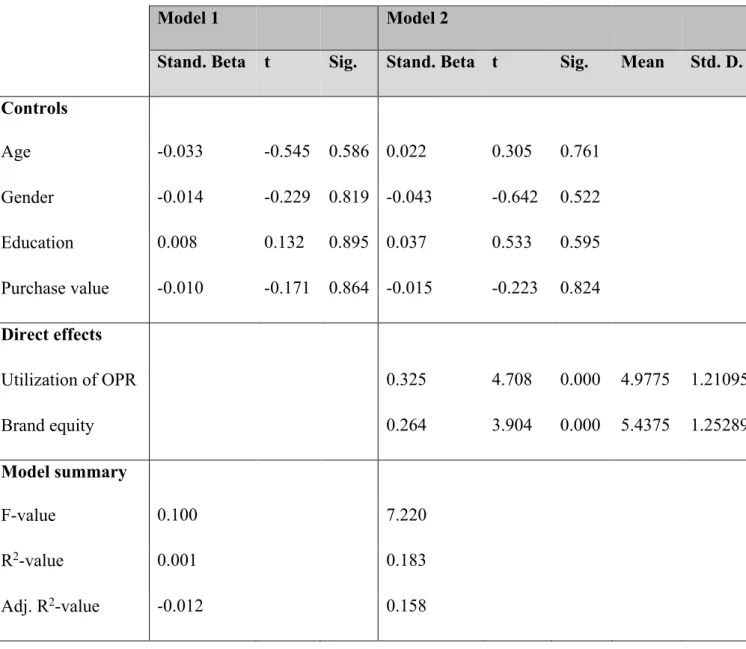

The testing of the hypotheses of this study was done with a linear regression analysis. In the first model we examine solely the controls and in the second we include the actual independent variables to test our hypotheses. Both hypotheses (H1, H2) are subsequently supported.

Within model 1 testing the controls, the regression reveals no statistical significance for any of the variables and a very low adjusted R2-value of -0.012 essentially not explaining any variance

of the dependent variable.

In the second model the test of brand equity affecting online purchase intent reveals a t-value of 4.708 indicating a robust effect and subsequently supporting the hypotheses H1. The utilization of online product reviews affecting online purchase intent has a t-value of 3.904 again implying a positive relationship and thus supporting the hypothesis H2. Both relationships have a p-value of 0.000 and are hence significant. An increase in brand equity by one standard deviation leads to an increase in purchase intent by 0.264 standard deviation. The effect of an increase in utilization of online product reviews by one standard deviation is larger, an increase by 0.325 standard deviation.

The model including the independent variables yields an adjusted R2-value of 0.158 hence

explaining a moderate amount of the variance of the dependent variable. All relevant values are presented in table 2:

Model 1 Model 2

Stand. Beta t Sig. Stand. Beta t Sig. Mean Std. D. Controls Age -0.033 -0.545 0.586 0.022 0.305 0.761 Gender -0.014 -0.229 0.819 -0.043 -0.642 0.522 Education 0.008 0.132 0.895 0.037 0.533 0.595 Purchase value -0.010 -0.171 0.864 -0.015 -0.223 0.824 Direct effects Utilization of OPR 0.325 4.708 0.000 4.9775 1.21095 Brand equity 0.264 3.904 0.000 5.4375 1.25289 Model summary F-value 0.100 7.220 R2-value 0.001 0.183 Adj. R2-value -0.012 0.158

Table 2: Regression Analysis

Looking at specific cohorts yields some interesting outcomes. For females the utilization of online product reviews is more important than for males yielding a change of 0.357 standard deviation in purchase intent for an increase of one standard utilization of online product reviews and respectively 0.2 for an increase in brand equity. Whereas in males the increase of utilization of online product reviews by one standard deviation yields only 0.174 standard deviation but an increase in brand equity yields 0.447 standard deviation. However, n is small for the male cohort in this regression model (n=61), so the explanatory power is very limited.

6 Discussion

The analysis yields outcomes largely within expectations. The overarching concept that brand equity and online product reviews both have a positive effect on purchase intent in an online setting is confirmed. However, when looking for a more important topic to focus on, none of the two concepts stands out indicating an importance to consider both aspects.

6.1 Controls

Regarding the control variables, the regression analysis yields no statistically significant relationship. However, existing literature identifies age as playing a role in the adoption of e-commerce (Sharma & Kurien, 2017) suggesting that older participants are less inclined to purchase online. A possible explanation can be a difference in risk preference of the respective age groups (Dillon & Reif, 2004). The age group over 30 is underrepresented within the dataset of this study so the results are not representative of the whole population.

6.2 Brand equity

Existing literature on brands, and brand equity especially, propose it playing an important role in consumer decision making. Prior studies confirm brand equity having an effect on purchase intent (Cobb-Walgren, et al., 1995).

Within the conceptualization of brand equity, both brand trust and brand recognition are used as compounding measures. Both have individually been suggested to have an impact on online purchase intent e.g. in research about brand trust by Gefen & Straub (2004) or brand recognition by Laroche, et al. (2012).

This paper indirectly supports these findings and identifies a positive correlation between the amalgamated brand equity and online purchase intent. Looking at the results in greater detail, this suggests both being familiar with a brand and trusting that brand having a positive effect on online purchase intent. This finding is quite fundamental although it supports one of the basic principles and methods of marketing i.e. brand building activities.

A likely explanation for this outcome lies in the risk mitigating effect that brand equity has in an online setting. When the product in question is branded by a familiar and trusted brand the perceived risk of buying that product online is lower than buying a product from an unknown producer.

6.3 Online product reviews

Research on both traditional word of mouth (Gupta & Harris, 2010) as well as eWOM (Huang & Chen, 2006) indicate effects on consumer behavior in that positive word of mouth as a positive effect on purchase intent. This effect extends itself also to online product reviews by Yang et al. (2016) acknowledging a likely explanation being the effect eWOM has on perceived risk of the customer.

This publication supports this view in that online product reviews have an effect on the customers purchase intent. More precisely the more respondents utilized online product reviews within their purchase decision, the higher was their resulting online purchase intent.

This allows the notion, that by reducing the perceived risk of shopping online through utilizing online product reviews the consumer increases the online purchase intent. Hence, trust in online product reviews is transferred to the actual product in question.

6.4 Comparative analysis

When comparing the impact of both brand equity and online product reviews none stands out as being considerably more influential for the consumer behavior in forming purchase decisions with the utilization of online product reviews having a slightly bigger effect. This suggests that focusing on either one concept and disregarding the other will likely lead to a lower effect on consumer behavior than an integrated strategy paying attention to both concepts. The difference in effect of only 0.061 standard deviation is too small to form a substantial opinion on relative importance. However, it could point in the direction that online product reviews, a much more recent phenomenon compared to brands, is having an important effect on online consumer behavior. Hence, this result should encourage marketers to broaden their view beyond mere brand building and in turn working with online product reviews.

6.5 Cohorts

When looking at the differences between male and female participants the male cohort is far more sensitive to increased brand equity than females. This suggests that males rely more on brands to form their purchase intention than females do, who seem to depend equally on both brands and online product reviews. There is little research going into this area but a paper by Fan & Miao (2012) suggests females perceiving a higher risk when shopping online resulting in a different online consumer behavior. This could explain why females rely on both brands and eWOM while males trust brands more.

7 Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to examine two of the drivers of purchase intent in an online setting, namely brand equity and the utilization of online product reviews. The study examines the respective effects these concepts have and reveals both being important elements to consider when shaping online consumer behavior.

Within this research we propose a composition of brand equity loosely following Keller (2008) but incorporating brand trust as the sum of past experiences with the brand and brand recognition as the awareness about the respective brand. Both experiential and perceptional elements of brand equity were included in our model. This integrates experiences with branded products as well as brand messages connecting those aspects of marketing.

The utilization of online product reviews was measured according to prior research by Bambauer-Sachse and Mangold (2011). Including both susceptibility as well as perceived credibility of online product reviews it reflects the use and perception of online reviews by consumers.

When compared, brand equity has a slightly higher effect however the difference being too small to choose one over the other but rather suggesting that both are important elements to consider. When abstracting both brand equity as well as the utilization of online product reviews it seems credible that both are aspects of the same urge of the consumer to minimize the inherent risks of online commerce. The initial idea of the researchers was that with the proliferation of technology, eWOM crowds out traditional B2C relationships such as brands is essentially unsupported.

7.1 Managerial Implications

For the marketing practitioner this study provides insights into the consumer behavior regarding online purchase intent. While the utilization of online product reviews has a slightly higher effect on online purchase intent than the brand equity the main take away is that both concepts are important aspects to consider in marketing for e-commerce. This implies that taking an active role in the online product reviews can have a similar effect to brand building activities. Prior research has shown that especially negative product reviews can have an adverse effect on brand equity (Bambauer-Sachse & Mangold, 2011) so that another conclusion can be that marketers can simply not get away with lower quality products in the contemporary world of highly proliferated eWOM.

7.2 Limitations

One limitation of this paper is the data basis. While the data was carefully checked for duplicates or other imperfections the data collection was not randomized. As a result, it does not allow for general assumptions for the general population since it is skewed to inhabitants of Germany, Finland and Sweden. However, it shows a tendency that is congruent with the results of prior studies.

Another limitation arises from the choice of operationalization for the chosen concepts. Especially brand equity is, as mentioned before, a deliberately vague concept as not to preemptively exclude aspects of the examination (Feldwick, 1996). Nonetheless, this study adapts the view of Keller (2008) but operationalizes it in a different way. This limits the ability to compare the results of this study with research that adheres to Keller (2008) approach more strictly.

Also, the operationalization of purchase intent is very broad. This way it does not correspond directly with the repurchase of the product mentioned by the participant. However, this was a necessity of the research design to allow for as many people as possible to partake in the survey. As for the analysis of the behavior of male and female participants, the male cohort is too small to form a legitimate conclusion. It can only serve to demonstrate a tendency that further research in this direction might go to and investigate further.

7.3 Suggestions for future research

While this study talks a lot about the perceived risk of customer in e-commerce it does not directly explore the risk preference of consumers and their subsequent preference of risk mitigation strategy (i.e. brands or WOM). Future research is suggested to include at least controls for risk preference. Another direction for future studies is investigating the effects different risk profiles of consumers have on their online purchasing behavior concerning brand equity and online product reviews.

Another more practical research question could be the ways in that marketers can influence the nature of online product reviews in a credible way. A lot of similar studies focus on brand communities, however most online product reviews are outside of environments controlled by the respective brands. Many of those review aggregators offer the possibility to answer on negative reviews. Hence, an interesting avenue for future research would be if an answer on an impactful negative review can have a positive effect on consumer behavior while maintaining trustworthiness.

Since the model used in this paper explains only a moderate amount of the variation in online purchase intent (adj R2 = 0.158) it would be interesting to see what other factors have an effect

on online consumer behavior. Furthermore, with the inherent importance of trust and online product reviews for the currently emergent platform economy research in this area could produce interesting observations.

Another aspect of consumer behavior that has not yet been thoroughly researched is the distinction between male and female consumers. The results of this study hint at a difference in behavior concerning the forming of online purchase intent. To research this with a larger dataset and including controls to delimit other influences on online purchase intent can possibly yield very interesting insights and in turn guidance for marketing professionals.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: Free Press.

Aaker, D. A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 102−121. .

Anastasiadou, E., Lindh, C., & Vasse, T. (2019). Are Consumers International? A Study of CSR, Cross-Border Shopping, Commitment and Purchase Intent among Online Consumers. Journal of Global Marketing, 32(4), 239-254.

Anuwichanont, J., & Rajabhat, S. D. (2011). The Impact Of Price Perception On Customer Loyalty In The Airline Context. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 9(9), 37-49. Balmer, J. (2010). Explicating corporate brands and their management: Reflections and

directions from 1995. Journal of Brand Management, Volume: 18 Issue: 3 Page: 180-196.

Bambauer-Sachse, S., & Mangold, S. (2011). Brand equity dilution through negative online word-of-mouth communication. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 18(1), 38-45.

Bickart, B., & Schindler, R. (2001). Internet forums as influential sources of consumer information. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 15 (3), 31–40.

Blodgett, J. G., Granbois, D. H., & Walters, R. G. (1993). The effects of perceived justice on complainants' negative word-of-mouth behavior and repatronage intentions. Journal of Retailing, 69(4), 399 ff.

Blumberg, B., Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2011). Business Research Methods. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Bredahl, L. (2001). Determinants of Consumer Attitudes and Purchase Intentions with Regard to Genetically Modified Foods - Results of a Cross-National Survey. Journal of Consumer Policy, 24(1), 23 ff.

Brown, J. J., & Reingen, P. H. (1987). Social Ties and Word-of-Mouth Referral Behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 350-362.

Chan, Y. Y., & Ngai, E. (2011). Conceptualising electronic word of mouth activity An input-process-output perspective. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 29(5), 488-516. Chatterjee, P. (2001). Online reviews: do consumers use them? Advances in Consumer

Research, 28 (1), 129–133.

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. Journal of marketing, 65(2), 81-93.

Chevalier, J. A., & Mayzlin, D. (2006). The Effect of Word of Mouth on Sales: Online Book Reviews. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(3), pp. 345-354.

Cobb-Walgren, C. J., Ruble, C. A., & Donthu, N. (1995). Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent. Journal of Advertising, 24(3), 25–40.

Commerce, U. D. (2020). Electronic Commerce and the Consumer. Retrieved from Electronic Commerce and the Consumer: https://library.unt.edu/gpo/oca/cb12.htm

Daugherty, T., & Hoffmann, E. (2014). eWOM and the importance of capturing consumer attention within social media. Journal of Marketing Communications, 20(1-2), 82-102. Delgado-Ballester, E., & Munuera-Alemán, J. L. (2005). Does brand trust matter to brand

equity? Journal of product & brand management.

Dick, A., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99-113.