Home- and occupation-based

interventions in stroke

rehabilitation: a scoping review

PAPER WITHIN Occupational Therapy, Thesis 1 AUTHOR: Eline Blindeman

SUPERVISOR: Caroline Fischl

EXAMINER Petra Wagman JÖNKÖPING June 2021

Occupational Therapy International

Review Article

Home- and occupation-based interventions in stroke

rehabilitation: a scoping review

Eline L.R. Blindeman

School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, 551 111 Jönköping, Sweden. Correspondence should be addressed to blel19ro@student.ju.se

Abstract

Introduction: Stroke puts a burden on the society as half of the stroke survivors have long

term care needs. After six months many stroke survivors cannot independently perform basic daily life activities, which makes living independently at home challenging. Stroke survivors who received occupational therapy are more independent for those activities. As more and more stroke survivors are discharged home faster, having an insight into the continued rehabilitation in the home environment is of great importance for the future.

Aim: The aim of this review was to map which occupation-based interventions occupational

therapists use in home-based stroke rehabilitation with the goal to improve basic activities of daily life.

Methods: A scoping review was chosen to map and to summarize the research content and to

identify possible research gaps. Data for this study was systematically collected by following Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. In total, six studies were obtained that met the inclusion criteria.

Results: The results show that a combination of intervention strategies is used and besides

Control Induced Movement Therapy the usage of activities as treatment came to the fore.

Conclusion: The results lead to the conclusion that occupation-based activities are used to

improve basic activities of daily life. The lack of detailed explanation of the interventions makes it difficult to implement those in daily life practice and therefore more descriptive interventions should be published to encourage evidence-based practice.

Key words: basic activity of daily life, home, occupation-based intervention, occupational

Introduction

Worldwide stroke is the second reason for mortality [1] and a major cause for disability [2]. Over 80 million people worldwide lived with the consequences of a stroke in 2016 [3] and stroke prevalence will only increase [4]. In Europe the cost of stroke was calculated at 60 billion euro in 2017 [5]. Not only the economic burden of a stroke will increase [5], but the high mortality and morbidity shows its effect on society since one out of two stroke survivors experience chronic consequences [6].

Having the fundamental skills to look after oneself and to participate in occupations supports the maintenance of health and well-being [7, 8]. Occupations are “the everyday activities that people do as individuals, in families and with communities to occupy time and bring meaning and purpose to life. Occupations include things people need to, want to and are expected to do” [9, para.2]. Performing and participating in normal daily life activities like self-care, productivity and leisure can be challenging after a strokebecause of physical and/or cognitive and/or emotional restrictions [7, 10].

Being discharged home is a goal for many stroke survivors [11] but restrictions in basic activities of daily life (BADL) can affect the clients’ capacity to live at home without help [12]. Activities related to BADL address bathing and showering, toileting and toilet hygiene, dressing, swallowing/eating, feeding, functional mobility, personal hygiene, grooming and sexual activity [13]. Half of the stroke survivors have care needs regarding BADL half a year after their stroke [14]. Legg et al. [14] explain that BADL are needed to survive in everyday life and therefore play an important role in stroke rehabilitation. Their systematic review concluded that stroke survivors are less dependent in BADL when they received occupational therapy. Recommendations made by The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [12] agree that occupational therapists should be involved in the stroke survivors

rehabilitation. BADL should be a part of the treatment process if limitations are experienced and should be practiced in as many occasions as possible [12]. Occupational therapy in stroke rehabilitation is based on the needs and objectives of the client and includes, but is not limited to: (re)training activities of daily life, learning to use assistive devices, adjust environments and regain functions that restrict participation in occupations (e.g. sensory loss, cognitive problems) [7, 10]. Assessment and treatment takes place in all stages of a stroke, described by Bernhardt et al. [15] as followed: acute stage (1-7 days), subacute stage (7 days – 6 months) and chronic stage (6 months post-stroke).

Occupational therapists guide stroke survivors in different environments e.g. neurological (intensive) care units, inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation facilities and in home care [10, 16]. The place of care delivery is changing from institution-based to home-based services [17-19]. Home-based stroke rehabilitation takes place in the clients’ home environment [19] and can start at any stage a stroke survivor is in [17]. As more and more stroke survivors return home faster [18] rehabilitation needs to continue after (a possible early) discharge. Winstein et al. [20] point out the importance of post-stroke rehabilitation because it aims to enable individuals to live as independently as possible in the future [7, 21, 22]. Not only can the length of stay in a hospital and readmittance be reduced due to home rehabilitation [17, 19, 22], it also leads to less dependent stroke survivors who better carry out daily life activities [7, 19].

The usage of daily activities as treatment intervention is a rather new topic in research [23]. Wolf et al. [24] found strong value for the usage of occupation-based interventions (OBI) aiming to increase activities of daily life (ADL), performed in the stroke survivors’ own home environment. Research done by Kim and Park [25] concluded that OBIs are fundamental to

use in stroke therapy, because it improves participation, quality of life and well-being of people with a hemiparetic stroke [26].

As occupations are central in occupational therapy practice, an occupation-based approach means that clients participate in daily life occupations “that offer a desirable level of pleasure, productivity and restoration and unfold as they ordinarily do in the person’s life” [27, pp. 167]. Interventions can be compensatory, educational, acquisitional or restorative in nature and give the occupational therapist the possibility to apply based, occupation-focused or a combined approach. The compensatory, acquisitional and restorative strategy can be occupation-based, whereas the education and teaching strategy doesn’t always include active engagement in the occupation and can therefore be seen as occupation-focused. The emphasis is on maintaining and/or restoring body functions and person factors when applying a restorative approach, whereas an acquisitional approach wants to reacquire or develop occupational performance skills. The compensatory strategy concentrates on adapting lost skills [27].

The growing need for effective stroke rehabilitation in the future [20] and the benefits of the home rehabilitation [19] make it of interest to gain insight into the use of home-based interventions offered by occupational therapists in stroke rehabilitation. Legg et al. [13] suggests that it could be more of interest to explore specific interventions instead of further investigating if occupational therapy is effective. NICE [12] agrees and suggests research regarding increasing BADL is needed, especially related to the content of treatment.

Therefore the aim of this study is to map which occupation-based interventions occupational therapists use in home-based stroke rehabilitation with the goal to improve basic activities of daily life.

Materials and methods

Since this review aims to map the research content, width and amount of studies that describe, report on and discuss on occupation-based interventions used in home-based stroke

rehabilitation, a scoping review was chosen as the method for this thesis. It can identify possible research gaps and key features related to the topic, but also gives the opportunity to summarize findings. No critical appraisal was done as a scoping review is not intended to provide recommendations or guidelines [28-30]. A systematic approach was placed central and therefore Arksey and O’Malley’s [31] framework for a scoping review was followed together with the recommendations made by Levac et al. [28] and the Joanna Briggs Institute [30]. The stages provided in the original framework are: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting data and collating, (5)

summarizing, and reporting results. The sixth stage, consulting scientists, stakeholders and/or experts, is optional and has not been done for this review [31].

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

To get a complete insight, a broad focus was set [29] and the research question holds the main concepts and the wanted outcome [28]. Which occupation-based interventions provided by an occupational therapist at home that intended to improve basic activities of daily life after a stroke are presented in literature?

As advised by Peters et al. [30] the research question was built according to the PCC

framework (Population or participants, Concept, Context). The targeted population consists of adult stroke survivors who live at home (participants) and who are guided by an occupational therapist applying OBIs related to BADL (concept). Crucial is that interventions are

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies 2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

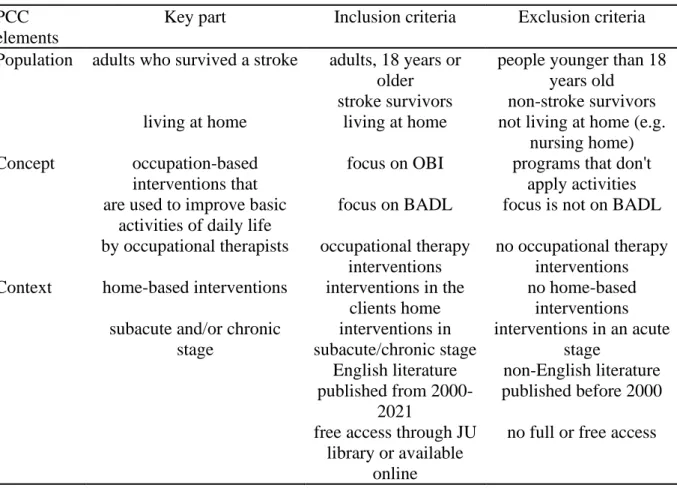

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) were designed based on the PCC model. These criteria supported the search process when determining whether studies could be included for data extraction or not [32].

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria according to the PCC framework.

PCC elements

Key part Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria Population adults who survived a stroke adults, 18 years or

older

people younger than 18 years old

stroke survivors non-stroke survivors living at home living at home not living at home (e.g.

nursing home) Concept occupation-based

interventions that

focus on OBI programs that don't apply activities are used to improve basic

activities of daily life

focus on BADL focus is not on BADL by occupational therapists occupational therapy

interventions

no occupational therapy interventions Context home-based interventions interventions in the

clients home

no home-based interventions subacute and/or chronic

stage

interventions in subacute/chronic stage

interventions in an acute stage

English literature non-English literature published from

2000-2021

published before 2000

free access through JU

library or available online

no full or free access

For studies to be included, the participants needed to be 18 years or older and living at home, where the intervention took place. If the intervention took place in the acute stage or in another environment than the clients’ home (like stroke units, outpatient rehabilitation centra, community centra, nursing homes) the study was excluded. Interventions were excluded when not being occupation-based, according to Fisher’s definition [27]. An occupational therapist had to be part of the team that performed the intervention otherwise the study was excluded. The focus of improvement lay on BADL and therefore studies that researched other areas of

occupations were excluded. Studies with insufficient details on the inclusion and exclusion criteria were excluded. The basic limits were literature written in English and published after 1999.

2.2 Identification of relevant studies

Relevant studies have been searched for through five electronic databases, reference lists, eight journals and grey literature [31]. Both quantitative and qualitative studies could be included in the findings. Systematic reviews that fit the search topic were obtained to check reference lists, but were not withhold for the findings.

2.2.1 Identification of studies via databases

The databases AMED, MEDLINE and CINAHL were chosen because of their extended collection of medicine and (bio)medical literature, focussing on nursing and allied health fields. For very relevant occupational therapy literature [32] OTseeker was used. Scopus was chosen because of its sources in medical and social science and for the provision of citations. All five databases have been searched with the same search string and limitations were set for language and year (Appendix 1). OTseeker has been verified manually for those limits. Scopus is a database that covers more than only the health care field, therefore extra filters have been added: “All open access” and the use of “subject areas” (medicine, health professionals and multidisciplinary) were included.

A trial search took place in the beginning of March 2021. Different search strings were tried and discussed with a librarian. The conclusion drawn from this search was that the search string could not be too wide nor too narrow. A combination of search terms and their

synonyms combined with Boolean words were used to identify literature. MESH words for stroke, occupational therapy and “activities of daily life” were used in CINAHL and MEDLINE and added to the search string.

“Occupation-based intervention” is a rather new term [23]. The trial search revealed that this term is not used much in research related to stroke, although it is at the base of occupational therapy [27]. It was kept in mind that the exact name would probably not appear in titles. Abstracts and articles have been manually checked to verify if studies used an OBI. Also the term “basic activities of daily life” needed to be approached in a similar way, as it usually appears in titles under a broader category such as “activities of daily life” or “daily life activities”, before it is specified to basic activity of daily life. When the specific basic activities of daily life (e.g. washing, dressing, grooming) were added to the search string in the trial search, very little results came up. Therefore it was decided, together with the librarian, that those terms were making the search too narrow and thus were excluded.

The stroke stages were not added in the search string, as literature is not concise on them. For this review the stages described in the introduction [15] were followed and checked manually.

2.2.2 Identification of relevant studies via other methods

The reference lists of obtained articles were manually searched through. Titles with similar key words as used during the electronic database search were listed. Citations in Scopus were searched for and titles with similar key words were added to the search list.

Eight journals, available through the Jönköping library and with free access through the Jönköping University library, published in English and that use peer reviews, were scanned through to find additional studies (Appendix 2).

Grey literature was searched through understanding its positive and negative consequences [33]. Websites related to stroke or occupational therapy or regarding stroke best practices and pathways were checked to find more studies. The searched websites were the American Occupational Therapy Association, Canadian Stroke Best Practices, NHS Stroke Pathway and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Websites from organisations that have been looked into were the World Stroke Organisation, American Stroke Association,

European Stroke organisation and Stroke Association. One abstract was selected, but did not fulfil the inclusion criteria.

Stage 3: Study selection

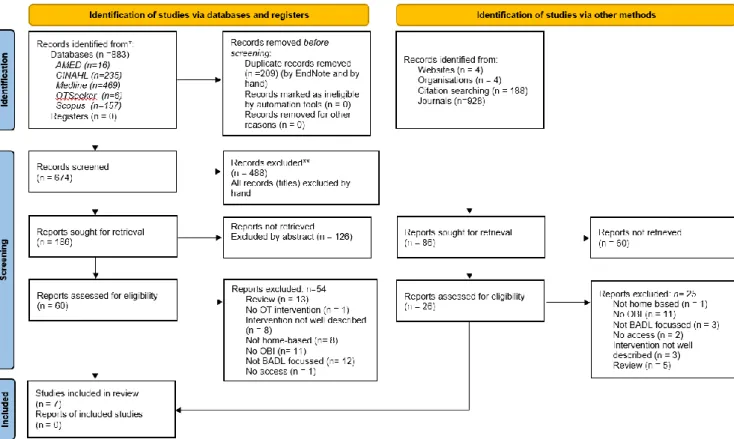

The literature search (Figure 1) was done in the second half of March 2021 and in the

beginning of April 2021. Articles were selected first on title, then on abstract and as lastly on the full-text. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were checked during this whole process.

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers).

**If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

Figure 1. Prisma 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews (Page et al., 2021).

3.1 Identification of studies via databases

Through the electronic database search 883 articles were found and were directly imported in EndNote online library to store and detect duplicates. After removing the duplicates, all titles (n=674) were screened, leading to 186 abstracts to be verified and to 60 full-text articles. Ten articles in total were obtained, of which four were systematic reviews. These four reviews were not included in the final list of selected articles, but their reference lists were checked.

3.2 Identification of relevant studies via other methods

Additionally the remaining nine articles were manually checked. In total 43 new titles were found. As the articles were already chosen based on title, first duplicates were removed before the next selection was done based on abstracts and full-text readings. One extra study could be obtained through this reference list search.

In total eleven articles were checked in Scopus for citations. Fifteen interesting titles came up in the 145 provided citation titles. Those 15 abstracts have been read and five full-text articles remained but did not fit the inclusion criteria.

During the online journal search (Appendix 2) only a few key words were used to keep the search wide, resulting in many hits (n= 928). Titles were selected, followed by removing duplicates. When reading through the abstracts only five full-text articles have been selected. None of those articles complied with the right inclusion criteria.

Also after searching in the grey literature, no study was selected. Research sections on the websites were scanned through trying to find more literature that fitted the criteria.

As a result of both database searches and manual searches, seven articles in total, all with a quantitative design, describing six projects could be included in this scoping review. Most studies were excluded based on the wrong concept or context.

Stage 4: Charting the data

Data was extracted from the selected articles and mapped in a table (Appendix 3): first author, year of publication and its origin, design and aim of the study, participants, intervention, protocol, key findings and ethical considerations were listed to have background information on the study characteristics and details regarding the research question [28, 30, 31].

Stage 5: Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

Summarizing and reporting the results was done in the last stage. An overview of all reviewed material is provided in descriptive text, accompanied with tables [31]. In the first part of the results section the study characteristics are given, followed by the interventions, categorized according to the models described by Fisher [27] and the key findings of the projects.

Ethical considerations

There are no participants involved when doing a scoping review, but for ethical

considerations, an attempt was made to do this review rigorously, transparently and with attention to search biases. To ensure rigor and transparency a full description of all stages of the search process, methods and outcomes are explained in-depth in the methodology section. Attention was paid to reduce biases by following the protocol described in the methodology section. Findings are written in a neutral way in respect to the original studies [33, 34]. Ethical reflections were made and information about whether articles underwent ethical review or received an ethical advisory opinion is given.

Research biases could have occurred due to methodology in data collection and analysis since only one author has written this review in a short time. The researcher is an occupational therapist, working in home-care, but not specifically trained to work only with stroke survivors. Efforts were made to be aware of this pre-understanding and to make no

assumptions in data collection and during the writing stage [35]. English is not the author’s native language so a possible language bias, in the form of small misunderstandings or wrong interpretation of writings, could have occurred. The content of certain words or English formulations that were not clear, have been discussed with someone who has a better English level than the author of this review.

Results

The data collection process arose seven quantitative studies [36-42] that described six projects that used occupation-based interventions to improve basic activities of daily life after stroke performed at the clients home and guided by an occupational therapist. The project done by Barzel et al. [42] analysed and described the findings of the previously started study [38].

Background information on the study characteristics can be found in appendix 3. The studies are equally divided over three continents: Europe, Asia and North-America and date between 2001 and 2015. The duration of the complete studies, with pre- and post-assessment, varies between four weeks [41] and seven months [37, 38]. Most researchers did their assessments before and immediately after the intervention took place. In one study no assessment was done right after the intervention stopped [39]. Three studies made follow-up measurements and one study implemented two intervention periods, with 6 weeks withdrawal in between. The studies were diverse in intervention, intervention time and stroke stage (see Appendix 3). The mean age of the participants varied between 55 and 75 years and participants were in different stages after their stroke: subacute stroke (n=2) and chronic stroke (n=4). Two studies were unclear about the stroke stage [39, 41] so assumptions have been made based on the background information given in the articles. Sample sizes ranged from one participant in a case study [40] up to 144 participants in a randomized control trial [38]. Some participants practiced daily without supervision, with a non-professional coach, and others practiced only together with the occupational therapist, or in a combination.

Three studies [39-41] reported which specific aspects of BADL the clients identified

themselves to improve. The targeted BADL were: bathing [39, 41], dressing [40, 41], eating [40], transferring and grooming [41].

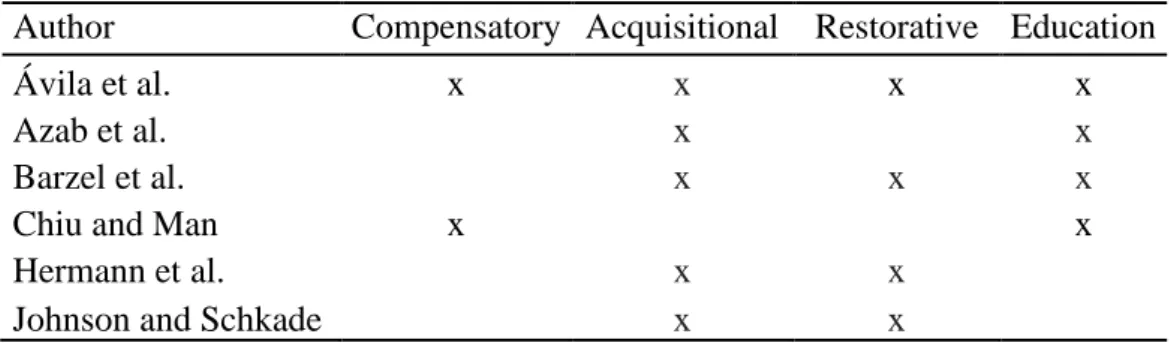

To answer the research question, the interventions used are structured according to Fisher’s [27] description of intervention model (Table 2) .

Table 2: Intervention strategies according to Fisher (2013).

Author Compensatory Acquisitional Restorative Education

Ávila et al. x x x x

Azab et al. x x

Barzel et al. x x x

Chiu and Man x x

Hermann et al. x x

Johnson and Schkade x x

Compensatory intervention

Chiu and Man [39] aimed to increase independency in bathing and trained the bathing activity itself using bathing devices.

Ávila et al. [36] made use of the compensatory strategy by adapting daily life activities, but they did not further explain in detail how they practiced and in relation to which BADL.

Acquisitional intervention

Control Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) was applied in the research of Azab et al. [37] and Barzel et al. [38, 42]. The participants in the intervention groups were stimulated to perform their normal daily life activities under the supervision of an instructed family member [37, 38]. In CIMT the less affected hand is placed in a mitten or resting glove so its function is restricted. The affected upper limb is forced to intensively and actively exercise and perform daily live activities [38].

In the study performed by Hermann et al. [40] the participant practiced independently twice a day. Occupation-based activities linked to the main goal of the client were trained. More details were not included so it can only be assumed that the intervention strategy had an acquisitional approach during this unsupervised trainings.

The home program of Ávila et al. [36] consisted of activities and techniques that directly aimed at training activities of daily life and intended to work towards the participants’ general goal. Interventions directly targeted meaningful activities chosen by the participants

themselves (ADL and IADL). It was not explained what the participants’ goals were, so no specification regarding BADL can be given.

Johnson and Schkade [41] practiced meaningful activities, based on the Occupational Adaptation framework, but they did not provide a lot of in-depth details regarding intervention strategy.

Restorative intervention

Task-related CIMT training with the clients’ non-professional coach focused on daily life activities (e.g. holding the handle of a cup and bringing it to the mouth, hanging up a clothes hanger, opening a drawer with a knob) [38].

A part of the study by Hermann et al. [40] contained individual online therapy twice a week. It was explained that this supervised therapy contained occupation-based, task-specific practices related to daily life activities e.g. using a fork and knife, tucking in and buttoning a shirt.

Avila et al. [36] included interventions aiming to restore or develop body functions or other personal factors: e.g. cognitive and sensorial stimulation, psychomotor skills, functional body posture training.

Johnson and Schkade [41] made use of skill-based activities but did not inform in-depth how they applied this or to which goal it was related.

Educational intervention

It should be noted that most studies [36-39] guided and/or educated family members or caregivers during their study. Chiu and Mann’s [39] first visit was related to education and

teaching without engaging in an actual bathing activity. The family members supervising the participants in the study performed by Azab et al. [37] were educated on CIMT, but no details were provided on who instructed the family members. The non-professional coaches in the study conducted by Barzel et al. [38] were instructed and guided by an occupational therapist during their home visits. Ávila et al. [36] had 10-15 min per session reserved for guiding caregivers. No details were shared so it cannot be decided if this was more an occupation-focused or occupation-based intervention.

Key findings of the projects

All projects noted positive results for their studies. The varied home program of Ávila et al. [36] concluded that their participants were less dependent in BADL and improved

significantly in nine out of ten activities on the Barthel Index. The projects that explored the use of CIMT at home [37, 38, 42] both measured positive effects on the performance of daily life activities and noted that those were maintained after six months. Azab et al. [37] found a significant increase in BADL functions and Barzel et al. [42] noted that home-based CIMT raised the use and quality of movement of the impaired arm in daily life activities and concluded that CIMT at home is more effective than traditional therapy. The participant that engaged in the telerehabilitation project of Herman et al. [40] was more satisfied with his performances in daily life activities and experienced less functional limits after the

intervention. Improved mobility and internal adaptation that could be applied to new skills were the key findings in the study done by Johnson and Schkade [41].

Providing extra sessions at home to train bathing devices increased significantly the participants’ independence and satisfaction regarding bathing [39].

Discussion

This review aimed to map which occupation-based interventions performed at home, aiming to improve basic activities of daily life after a stroke, were presented in literature. Although making use of daily activities in therapy is a rather new topic in research [23], activities were at the base of all study interventions. The intervention that was used twice and was best described was CIMT. Azab et al. [37] noted significant improvements on BADL, as well as Barzel et al. [42] who concluded that CIMT at home increases the use of the affected upper limb in ADLs. Those findings support the strong recommendations made by the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) [43] to apply CIMT in therapy when targeting improvement in activity engagement.

Further studies made use of activities to improve BADL, but did not go further into detail. All four intervention models [27] were identified. At least two strategies were always combined and one study implemented all strategies in their home program. Having a combined approach makes it possible to tailor therapy to the client’s needs and wishes and target different goals at the same time.

Not all studies specified the targeted basic activities of daily life, so no categorization according to AOTA [13] categories could be made to present the results. Since the overall lack in intervention descriptions, it could be discussed further whether CIMT had a more acquisitional or restorative approach and whether the interventions from other studies have been categorized well.

The ‘Action Plan for Stroke in Europe 2018-2030’ advices to train BADL in the clients home environment up to one year after a stroke [16]. It should be noted that for most participants in this review, that time had already past. Often it is found in literature that the subacute stage is

the most important stage to regain and train function after stroke. All participants in the studies had improved their performances and/or increased their independence regarding BADL, making it of interest to further explore different intervention strategies in a chronic stage. The question could be raised why certain participants only were provided with occupational therapy in a late stage or why BADL had to be targeted in a chronic stage. On the other hand it could be questioned why there were so little studies found that were performed in the first year after a stroke, as the action plan for stroke suggest. This review can’t generally confirm that targeting BADL is a key feature in early home stroke

rehabilitation, although the importance of BADL regarding early discharges home has been explained.

Home rehabilitation has proven its value [19] in the needed stroke rehabilitation for the future [20]. The findings from the included studies in this scoping review are in line with the review of Wolf et al. [24], who concluded that OBIs performed in the home environment affect positively the performance in BADL. To gain more insight on the used home-based

interventions occupational therapists perform, more research is needed. This review identified a clear research gap, namely that it is difficult to find studies who describe in-depth their performed intervention in home stroke rehabilitation. The inconsistency in descriptions makes it hard for occupational therapists to apply the interventions to their daily life practices. It could be of interest in regards to future evidence-based practice to publish more in-depth described interventions in occupational therapy journals.

Methodological considerations

Although five out of six steps from Arksey and O’Malley’s’ framework [31] have been followed very thoroughly, the last step, consulting experts, has not been taken. This last step could have been valuable as it might provide an up-to-date opinion on interventions used

nowadays in daily practice. Not all databases, journals and grey literature sources were searched, making it possible that literature that fitted the inclusion criteria was not identified. A wider journal search could be considered, given the spread in origin of the articles. Only six projects, all found in scientific journals, have been included in this review, which raises some questions. It was reflected that there might have been too many search words in the search string and/or the topic of this review was too narrow. For further research it could be kept in mind to widen the overall search question and reflect on the year limitation (2000-2021) that was set. Only English literature was searched, so missing out on literature because of

language is a possibility.

An extensive trial search has been done and discussed with a librarian in order to discuss the approach chosen and possible adjustments that could be made. It was clear that the search words could not be too specific. For this reason many abstracts and articles had to be checked manually to verify the right inclusion and exclusion criteria. Since several studies did not describe their interventions in sufficient detail, it is possible that relevant studies were not found or have been excluded. The focus of this review was on BADL but because so little articles could be obtained, a few studies that had both BADL and IADL training goals in their study have been included. It has been tried to extract the IADL interventions and only to use the BADL interventions in this review. The IADL interventions had only a very small percentage in some articles.

Ethical considerations from the studies have been kept in mind, although they did not affect the content of this review. A small lack of detail was found, as one study did not inform if their participants had provided informed consent.

Conclusions

Studies were found that used occupation-based interventions in home stroke rehabilitation to improve BADL. Interventions that came across in this scoping review consisted of CIMT and performing the basic activities of daily life as treatment intervention. Not many studies that provided a detailed description of interventions in home stroke rehabilitation were found. It can be concluded that occupational therapists use activities as treatment, but it seems that OBIs at home (the place where the client lives and needs to participate eventually) were not used too often, not researched or not published a lot.

Future research could explore further, both in qualitative and quantitative research, the OBIs occupational therapists use in stroke home rehabilitation.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest exists.

Data Availability

Extra information related to the data collection is available upon request.

Funding Statement

This review was performed as part of the Jönköping University Master of Science with a Major in Occupational Therapy. No funding was received.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by the Jönköping University, Sweden. I would like to thank my supervisor Caroline Fischl for her help and advice during this process. Thanks also go to my fellow students for moral support.

References

[1] World Health Organization. (2020). The top 10 causes of death.

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

[2] Katan, M., & Luft, A. (2018). Global Burden of Stroke. Seminars in Neurology 38, 208-211. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1649503

[3] Johnson, C., Nguyen, M., Roth, G., Alam, T., Abd-Allah, F., Adeoye, A., Aichour, A., Arauz, A., Ärnlöv, J., Banach, M., Belayneh, Y., Bensenor, I., Bijani, A., Bikbov, B., Cahuana-Hurtado, L., Catalá-López, F., Choi, J., Christensen, H., Cortinovis, M., … de Courten, B. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurology,

18(5), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30034-1

[4] Gorelick, P. (2019). The global burden of stroke: persistent and disabling. Lancet

Neurology, 18(5), 417–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30030-4

[5] Luengo-Fernandez, R., Violato, M., Candio, P., & Leal, J. (2020). Economic burden of stroke across Europe: A population-based cost analysis. European Stroke Journal, 5(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396987319883160

[6] Donkor, E. (2018). Stroke in the 21st Century: A Snapshot of the Burden, Epidemiology, and Quality of Life. Stroke Research and Treatment, 2018, 3238165–3238165.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3238165

[7] Legg, L. A., Lewis, S.R., Schofield-Robinson, O.J., Drummond, A., & Langhorne, P. (2017). Occupational therapy for adults with problems in activities of daily living after stroke. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 7, CD003585.

[8] Townsend, E. A., & Polatajko, H. J. (2013). Enabling occupation II: Advancing an

occupational therapy vision for health, well-being, & justice through occupation (2. ed.).

CAOT Publications ACE.

[9] World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (n.d.). About Occupational Therapy. https://www.wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy

[10] American Occupational Therapy Association. (2015). The Role of Occupational Therapy in Stroke Rehabilitation.

https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy/Professionals/RDP/stroke.aspx

[11] Clery, A., Bhalla, A., Bisquera, A., Skolarus, L.E., Marshall, I., McKevitt, C., Rudd, A., Sackley, C., Martin, F.C., Manthorpe, J., Wolfe, C., & Wang. Y. (2020). Long-Term Trends in Stroke Survivors Discharged to Care Homes: The South London Stroke Register. Stroke (1970), 51(1), 179-185.

https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026618

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2016). National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke 5th edition. https://www.strokeaudit.org/Guideline/Guideline-Home.aspx

[13] American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy,

74(Suppl.2), 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

[14] Legg, L., Drummond, A., Leonardi-Bee, J., Gladman, J., Corr, S., Donkervoort, M., Edmans, J., Gilbertson, L., Jongbloed, L., Logan, P., Sackley, C., Walker, M., & Langhorne, P. (2007). Occupational therapy for patients with problems in personal activities of daily living after stroke: systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ,

335(7626), 922–925.

[15] Bernhardt, J., Hayward, K.S., Kwakkels, G., Ward, N.S., Wolf, S.L., Borschmann, K., Krakauer, J.W., Boyd, L.A., Carmischal, S.T., Corbett, D., & Cramer, S.C. (2017). Agreed definitions and a shared vision for new standards in stroke recovery research: The Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable taskforce. International Journal of Stroke, 12(5), 444-450. DOI: 10.1177/1747493017711816

[16] Norrving, B., Barrick, J., Davalos, A., Dichgans, M., Cordonnier, C., Guekht, A., Kutluk, K., Mikulik, R., Wardlaw, J., Richard, E., Nabavi, D., Molina, C., Bath, P.M., Stibrant Sunnerhagen, K., Rudd, A., Drummond, A., Planas, A., & Caso, V. (2018). Action plan for stroke in Europe 2018-20130. European Stroke Journal, 3(4), 309-336.

doi: 10.1177/2396987318808719

[17] Mayo, N. (2016). Stroke Rehabilitation at Home: Lessons Learned and Ways Forward.

Stroke (1970), 47(6), 1685–1691. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.011309

[18] Mountain, A., Patrice Lindsay, M., Teasell, R., Salbach, N., de Jong, A., Foley, N., Bhogal, S., Bains, N., Bowes, R., Cheung, D., Corriveau, H., Joseph, L., Lesko, D., Millar, A., Parappilly, B., Pikula, A., Scarfone, D., Rochette, A., Taylor, T., … Cameron, J. (2020). Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Rehabilitation, Recovery, and Community Participation following Stroke. Part Two: Transitions and Community Participation Following Stroke. International Journal of Stroke, 15(7), 789–806. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493019897847

[19] van der Veen, D., Döpp, C., Siemonsma, P., Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M., & Sande, W. (2019). Factors influencing the implementation of Home-Based Stroke Rehabilitation: Professionals’ perspective. PloS One, 14(7), e0220226-.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220226

[20] Winstein, C., Stein, J., Arena, R., Bates, B., Cherney, L., Cramer, S., Deruyter, F., Eng, J., Fisher, B., Harvey, R., Lang, C., MacKay-Lyons, M., Ottenbacher, K., Pugh, S., Reeves, M., Richards, L., Stiers, W., & Zorowitz, R. (2016). Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke (1970), 47(6), e98– e169. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000098

[21] Blomgren, C., Samuelsson, H., Blomstrand, C., Jern, C., Jood, K., & Claesson, L. (2019). Long-term performance of instrumental activities of daily living in young and middle-aged stroke survivors-Impact of cognitive dysfunction, emotional problems and fatigue.

[22] Hillier, S., & Inglis-Jassiem, G. (2010). Rehabilitation for community-dwelling people with stroke: home or centre based? A systematic review. International Journal of Stroke,

5(3), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00427.x

[23] Weinstock-Zlotnick, G., & Mehta, S.P. (2019). A systematic review of the benefits of occupation-based intervention for patients with upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of Hand Therapy, 32, 141-152.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2018.04.001

[24] Wolf, T. J., Chuh, A., Floyd, T., McInnis, K., & Williams, E. (2015). Effectiveness of occupation-based interventions to improve areas of occupation and social participation after stroke: An evidence-based review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69, 6901180060. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.012195

[25] Kim, S., & Park, J. (2019). The Effect of Occupation-Based Bilateral Upper Extremity Training in a Medical Setting for Stroke Patients: A Single-Blinded, Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, 28(12), 104335– 104335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104335

[26] Ahn, S.N. (2019). Effectiveness of occupation-based interventions on performance’s quality for hemiparetic stroke in community-dwelling: A randomized clinical trial study.

Neuro Rehabilitation 44, 275–282 DOI:10.3233/NRE-182429

[27] Fisher, A.G. (2013). Occupation-centred, occupation-based, occupation-focused: Same, same or different? Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20, 162–173. DOI: 10.3109/11038128.2012.754492

[28] Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the

methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69–69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

[29] Munn, Z., Peters, M., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143– 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

[30] Peters, M.D.J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A.C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI

Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI, 2020. Available

from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12 [31] Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological

framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

[32] Taylor, M. C. (2007). Evidence-based practice for occupational therapists. Blackwell Science Ltd.

[33] Zawacki-Richer, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., & Buntins, K. (2020).

Systematic Reviews in Educational Research. Methodology, Perspectives and Application. Springer.

[34] Wager, E., & Wiffen, P. (2011). Ethical issues in preparing and publishing systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 4(2), 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-5391.2011.01122.x

[35] Chalmers, A. (2013). What is this thing called science? Maidenhead: Open university press.

[36] Ávila, A., Durán, M., Peralbo, M., Torres, G., Saavedra, M., & Viana, I. (2015). Effectiveness of an Occupational Therapy Home Programme in Spain for People Affected by Stroke. Occupational Therapy International, 22(1), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1377

[37] Azab, M., Al-Jarrah, M., Nazzal, M., Maayah, M., Sammour, M. A., & Jamous, M. (2009). Effectiveness of constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) as home-based therapy on Barthel Index in patients with chronic stroke. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation,

16(3), 207-211. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1603-207

[38] Barzel, A., Ketels, G., Tetzlaff, B., Krüger, H., Haevernick, K., Daubmann, A.,

Wegscheider, K., & Scherer, M. (2013). Enhancing activities of daily living of chronic stroke patients in primary health care by modified constraint-induced movement therapy (HOMECIMT): Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-334

[39] Chiu, C.W.Y., & Man, D.W.K. (2004). The effect of training older adults with stroke to use home-based assistive devices. Occupation, Participation and Health, 24(3), 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/153944920402400305

[40] Hermann, V. H., Herzog, M., Jordan, R., Hofherr, M., Levine, P., & Page, S. J. (2010). Telerehabilitation and electrical stimulation: an occupation-based, client-centered stroke intervention. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the

American Occupational Therapy Association, 64(1), 73-81.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.64.1.73

[41] Johnson, J. A., & Schkade, J. K. (2001). Effects of an occupation-based intervention on mobility problems following a cerebral vascular accident. Journal of Applied

Gerontology, 20(1), 91-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/073346480102000106

[42] Barzel, A., Ketels, G., Stark, A., Tetzlaff, B., Daubmann, A., Wegscheider, K., van den Bussche, H., & Scherer, M. (2015). Home-based constraint-induced movement therapy for patients with upper limb dysfunction after stroke (HOMECIMT): a

cluster-randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet. Neurology, 14(9), 893-902. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00147-7

[43] American Occupational Therapy Association. (2015). Occupational therapy practice guidelines for adults with stroke.

https://www.guidelinecentral.com/summaries/occupational-therapy-practice-guidelines-for-adults-with-stroke/#section-society

Appendix 1. Overview of the electronic database search with detailed information on the search string, used limits and hits.

Database search

19.3.2021

Database Search string

AMED (stroke OR "cerebrovascular accident" OR CVA) AND ("occupational therapy" OR "occupational therapist") AND (adult* OR aged OR elderly) AND ("occupation-based" OR "activity-based" OR "daily activities" OR "daily life activities" OR ADL OR BADL OR PADL OR "occupational therapy intervention")

Limits English, 2000-2021

Hits 16

MEDLINE ((MH Stroke) OR (MH Stroke Rehabilitation) OR stroke OR "cerebrovascular accident" OR CVA) AND ((MH Occupational therapy) OR "occupational therapist" OR "occupational therapy") AND ((MH "Activities of Daily Living") OR "occupation-based" OR "activity-based" OR "daily activities" OR "daily life activities" OR ADL OR BADL OR PADL OR "occupational therapy intervention") AND (adult* OR aged OR elderly)

Limits English, 2000-2021

Hits 469

CINAHL ((MH Stroke) OR (MH Stroke Patients) OR stroke OR "cerebrovascular accident" OR CVA) AND ((MH

Occupational therapy) OR "occupational therapist" OR "occupational therapy") AND (adult* OR aged OR elderly) AND ((MH "Activities of Daily Living") OR "occupation-based" OR "activity-based" OR "daily activities" OR "daily life activities" OR ADL OR BADL OR PADL OR "occupational therapy intervention")

Limits English, 2000-2021

Hits 235

OTseeker (stroke OR "cerebrovascular accident" OR CVA) AND ("occupational therapy" OR "occupational therapist") AND (adult* OR aged OR elderly) AND ("occupation-based" OR "activity-based" OR "daily activities" OR "daily life activities" OR ADL OR BADL OR PADL OR "occupational therapy intervention")

Limits not possible

Hits 6

Scopus

(stroke OR "cerebrovascular accident" OR CVA) AND ("occupational therapy" OR "occupational therapist") AND (adult* OR aged OR elderly) AND ("occupation-based" OR "activity-based" OR "daily activities" OR "daily life activities" OR ADL OR BADL OR PADL OR "occupational therapy intervention")

Limits English, 2000-2021 All open access, subject area

Hits 157

Total

Appendix 2. Detailed information on the limits and search words used in the journal search.

Journal search Search string Occupational Therapy

International

checked manually Date 20.3.2021

Limits not possible

Hits 39

Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy

stroke AND home intervention Date 21.3.2021

Limits English, 2000-2021

Hits 167

British Journal of Occupational Therapy

stroke AND home intervention Date 21.3.2021

Limits English, 2000-2021

Hits 223

Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy

stroke AND home intervention Date 24.3.2021

Limits English, 2000-2021

Hits 90

Disability and rehabilitation stroke AND home AND "occupational therapy" AND "activities of daily life"

Date 24.3.2021

Limits English, 2000-2021, full access

Hits 47

Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation occupational therapy AND home intervention Date 25.3.2021

Limits English, 2000-2021, full access

Hits 172

Stroke occupational therapy AND home intervention Date 25.3.2021

Limits English, 2000-2021

Hits 94

International Journal of Stroke occupational therapy AND home intervention Date 9.4.2021 Limits English, 2006-2021 Hits 96 Total hits 928

Appendix 3. Data extraction table. Author

Year publication Origin

Design and aim of the study

Participants Stroke stage * Age in years

Intervention Protocol Key findings Ethical

considerations Ávila et al. 2014 Spain Multiple-baseline intrasubject design with treatment withdrawal period To explore if cognitive and perceptive skills & basic activities of daily life improve after an

occupational therapy home program.

n=23

Chronic stroke stage Age 51 – 68, mean 61 years

10 men and 13 women

2x/week, 90min/session, 12 weeks (intervention 1), 8 weeks (intervention 2)

Activities of daily life training as part of bigger home program. Activities and techniques of physical, cognitive, social and functional nature, according to client’s needs. Per session 35 min for the main purpose of the session and 30 min to work with daily life activities. 10-15 minutes counselling the family or the main caregiver, 5-10 minutes for orientation.

Pre-test, intervention 1, post -test 1, 6 weeks withdrawal, post-test 2, intervention 2, post-test 3 Significant improvement in participants’ cognitive skills and functional independence. Informed consent obtained Azab et al. 2015 Jordan RCT To investigate the short -and long-term effect of CIMT** as a home-based therapy program.

n=37

Subacute stroke stage Control group n=17 (12 men, mean 58 years/ 5 women, mean 55 years) Intervention group n=20 (16 men, mean 58 age/ 4 women, mean 60 years)

Control group: 4 weeks, 3x/week, 40min/session traditional therapy (occupational therapy and physiotherapy)

Intervention group: 4 weeks, 3x/week,

40min/session traditional therapy (occupational therapy and physiotherapy)+ CIMT 6-7h/day, 4 weeks

Traditional therapy without the use of the mitt. CIMT was supervised and encouraged by a trained family member. Encouraged to practice full functional activities.

Pre-test, intervention, post-test 1, assessment after 6 months Significant improvement on Barthel Index for the intervention group compared to the control group. After 6 months follow-up, Barthel Index indicated that the obtained profits were maintained. Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent obtained

Barzel et al. 2013 and Barzel et al. 2015 (findings) Germany RCT To evaluate the efficacy of ‘CIMT at home’, compared with conventional therapy, with regard to participation in daily life activities. To explore the effects six months post-intervention.

n = 144

Chronic stroke stage Control group (n=71), 45 months post-stroke Mean 65 age Intervention group (n=82), 56 months post-stroke Mean 62 age

Control group: 4 weeks, 10 occupational therapy sessions (or 250 to 300 minutes). ‘Therapy as usual’ in the patients’ homes or at the therapists’ practices.

Intervention group: CIMT 4 weeks, 5 days/week, 4-6h/day of which 2h/day with non-prof coach +5 occupational therapy home visits (250-300min); first 2 visits 50–60 min/first week -make an individually tailored home training program, focusing on everyday practice and to instruct non-professional coaches.

3 home visits of 50–60 min in the next 3 weeks to supervise the progress. Patient receives 2-3 additional exercises weekly (10–15 exercises in total). Pre-test, intervention, post-test 1, assessment after 6 months Home-based CIMT enhances the use of the stroke-affected arm in daily life activities more effectively than

conventional therapy. At 6 month follow-up, upper limb performance in both groups had improved but quality of movement in the upper limb had a significantly higher improvement in the intervention group.

Ethics committee approval and informed consent obtained Chiu and Man 2004 Hong Kong RCT To evaluate if an additional home training on bathing devices would improve the rate of use, personal independence and service satisfaction. n=53 Assumption of subacute stage Age 55-92, mean 72 years Control group (n=23) Intervention group (n=30)

Training of devices with both groups while they were in the hospital.

Control group: pre-discharge home visit to prepare a suitable environment, no treatment post-discharge.

Intervention group: 2 sessions, max 3 in the use of bathing devices immediately after discharge. Demonstration, education, safety, bathing practice

Pre-test, intervention, assessment after 3 months

The intervention group improved significantly in performance and satisfaction. The use of bathing devices was relatively higher in the intervention group (96.7%) than in the control group (56.5%). Personal independence and functioning were found to be better in the intervention group. Ethical approval obtained Hermann et al. 2010 US Case study To examine the efficacy of a telerehabilitation arm program. n=1

Chronic stroke stage 62-year-old man

4 weeks, 2x/week, 30 min/ online occupational therapy session

+ 3x/week, 2x 30min/day unsupervised Online therapy focused on increasing affected upper-extremity use during daily life activities

Pre-test (week 1), intervention (week 2-5), post-test (week 6)

Reduced impairment and functional limitation in the upper limb. Enhanced satisfaction and performance in activities of daily life.

Consent form approved and informed consent obtained

identified by the participant. Occupation-based, task-specific practice of activities of daily living. Unsupervised home sessions: tasks and functional activities. Goals were related to basic activities of daily life tasks (dressing and eating) and

instrumental activities of daily life.

Johnson & Schkade 2001 US Case study To explore the usefulness of a new occupational therapy approach (Occupational Adaptation Frame of Reference) in treatment of mobility problems. n=3 Assumption of chronic stroke stage Age 65-88

4 weeks, 2x/week, 45min/session

Skill-based activities and practice of meaningful activities with focus on adaptation when performing meaningful activities, based on Occupational Adaptation Frame of Reference

Pre-test, intervention, post-test

All participants

improved in mobility and overcame their

occupational challenges. They showed internal adaptation and applied new skills.

Informent consent obtained

* acute stage (1-7 days), subacute stage (7 days – 6 months) and chronic stage (6 months post-stroke) [15] ** Control Induced Movement Therapy