Green lifestyle,

where to go?

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Consumer Behavior NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTs

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Marketing SUPERVISOR: Sambit Lenka

AUTHOR: Haina Zhang & Thanh Ha Nguyen JÖNKÖPING May 2020

How social media influencers moderate the

intention – behavior gap within the

i

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Green lifestyle, where to go? How social media influencers moderate the intention – behavior gap within the ecological lifestyle context

Authors: Haina Zhang and Thanh Ha Nauyen Tutor: Sambit Lenka

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Green lifestyle, green lifestyle adoption, intention – behavior gap, consumer behavior, social media influencers, influencer marketing

Abstract

Background: Due to the severe environmental problems, a green ecological lifestyle has gradually become the mainstream trend nowadays. Though the researchers have indicated that consumers who are concerned about environment are more likely to participate in the adoption of green behavior, data shows that there are still not a large portion of green consumers among all intended people. The phenomenon when consumers intend to do an action, but many of them fail to translate intentions into action is called intention-behavior gap, which is contributed by plenty of barriers. Together with the emergence of green lifestyle, social media nowadays becomes a part of people daily lives and social media influencers also become an efficient marketing and communication tool as they play a prominent role in spreading awareness and influence the behavior change. The researchers see the potential of SMIs to moderate the IB gap in ecological lifestyle context, hence, the research was built to explore the phenomenon.

Purpose: The purpose of the study is to explore how social media influencers moderate the intention behavior gap in adopting green lifestyle behaviors. To do that, the researchers analyze people’s barriers in adopting ecological behavior and their attitude towards green lifestyle influencers and find the connection. It thereby helps the influencers, marketers to understand the

ii

consumers’ perception in terms of green lifestyle, then discover potential opportunities and propose suitable marketing strategies to ecological company and organization.

Method: Following the purpose of this study, an exploratory qualitative research is carried out using an induction method. Specifically, in-depth interviews with open-ended questions were conducted to have an insight into the participants’ attitude, intention and behavior towards green lifestyle adoption and social media influencers.

Conclusion: The research results show that the social media influencers can moderate the intention – behavior gap within ecolgocial lifestyle adoption by affecting directly to green intended consumers’ behaviors. The influence includes the quality and quantity of contents, the authenticity and credibility from influencers and information, and their personal background and characteristics. The study also points out its delimitations and limitations, proposes several possibilities for managerial implications, as well as some suggestions for future research.

iii

Acknowledgement

Writing this master thesis is a precious opportunity for us to have self-improvement. Also it is an exciting journey with full of challenges and rewarding moments through the teamwork. We would like to express our deep gratitude to those who have helped us to complete this study.

First of all, we would sincerely thank professor Sambit Lenka for being an amazing supervisor who has patiently gave us useful comments and valuable suggestions for improving the research. We appreciated all the valuable feedback, suggestions, discussions, and critics that helped us to develop quality research.

Furthermore, we would like to express our sincere appreciation to our fellow students in the seminar group for their time detailed and helpful feedback during th seminar sessions which helped us to enhance the quality of the thesis.

Last but not least, we are grateful to the participants who spent their precious time for participating in the interviews and contributed to this paper with many interesting points of view.

iv

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background and motivation ... 1

1.2 Purpose ... 4

1.3 Research question ... 5

1.4 Delimitations ... 5

1.5 Thesis structure ... 6

2

Literature Review ... 7

2.1 Eco-lifestyle and IB gap ... 7

2.1.1 Identify ecological lifestyle and ecological consumers ... 7

2.1.1.1 Ecological lifestyle ... 7

2.1.1.2 Ecological consumers ... 8

2.1.2 Intention-behavior gap ... 9

2.1.2.1 Intention and behavior relation ... 9

2.1.2.2 Intention Behavior gap ... 9

2.2 The relevance of SMIs in consumer behavior ... 14

2.2.1 The importance of IM and SMIs ... 14

2.2.1.1 Why influencer marketing is important to study? ... 14

2.2.1.2 Who are social media influencers? ... 15

2.2.2 SMIs and consumer behavior ... 15

2.2.2.1 How SMIs impact on consumers’ intention ... 16

2.2.2.2 How SMIs impact on consumers’ behavior ... 16

2.2.2.3 How SMIs moderate the IB gap ... 16

2.3 Summary ... 17

3

Methodology ... 19

3.1 Research approach ... 19 3.1.1 Research philosophy ... 19 3.1.2 Research design ... 20 3.2 Data collection ... 21 3.2.1 Semi-structured interviews ... 21 3.2.2 Sampling ... 223.2.3 Interview guide and structure ... 23

3.3 Data analysis ... 24 3.3.1 Interview summary ... 24 3.3.2 Analysis method ... 24 3.4 Ethical considerations ... 26 3.4.1 Research ethics ... 26 3.4.2 Research quality ... 26

4

Empirical results and analysis ... 28

4.1 Participants’ behavior ... 28

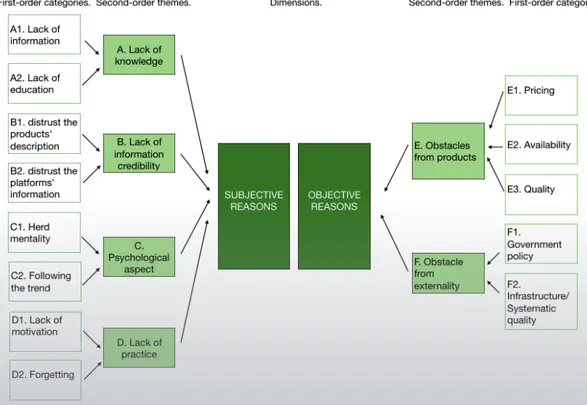

4.2 Intention-behavior gap in green behavior adoption ... 30

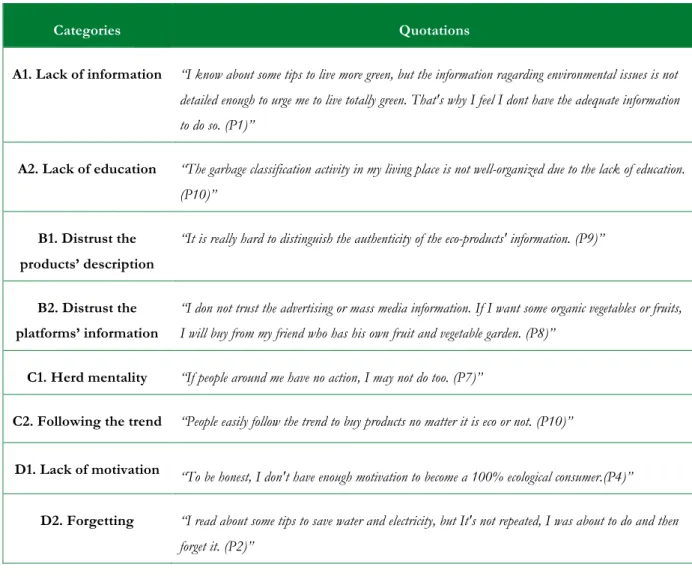

4.2.1 Subjective reasons ... 31

4.2.1.1 Lack of knowledge ... 31

4.2.1.2 Lack of information credibility ... 32

4.2.1.3 Psychological aspect ... 32

4.2.1.4 Lack of practice ... 33

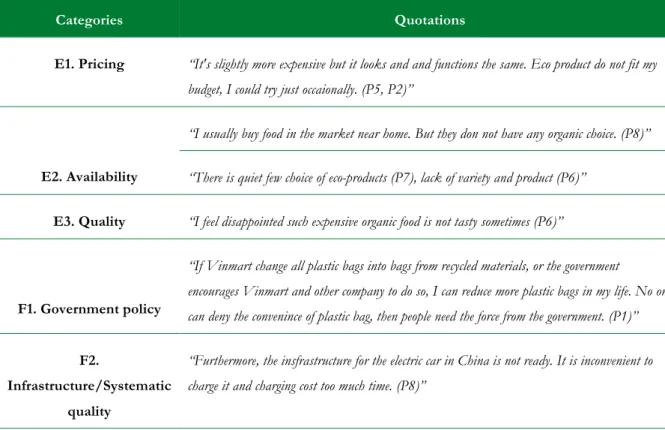

4.2.2 Objective reasons ... 34

v

4.2.2.2 Obstacles from externality ... 35

4.3 How SMIs affect the consumers' behaviour? ... 36

4.3.1 The quality and quantity of contents ... 37

4.3.1.1 Content quality ... 37

4.3.1.2 Content quantity ... 38

4.3.2 The influencers’ trustworthiness ... 39

4.3.2.1 Authenticity ... 39

4.3.2.2 Credibility ... 40

4.3.3 The SMI’s personal branding ... 41

5

Discussion ... 44

5.1 Intention – behavior gap in the ecological context ... 44

5.2 How SMIs moderate the IB gap in ecological context ... 45

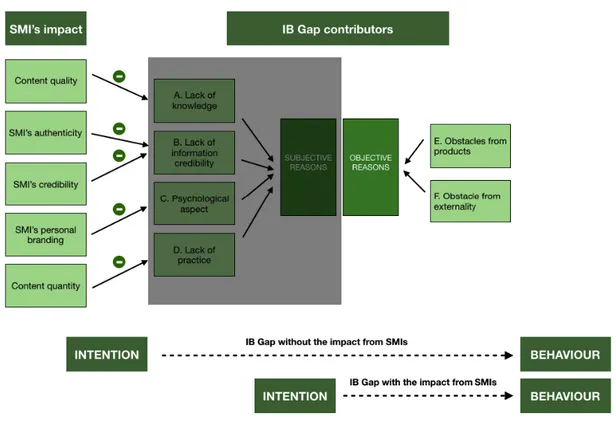

5.3 Final framework ... 47

6

Conclusion ... 49

6.1 General conclusion ... 49

6.2 Theoretical contributions ... 50

6.3 Societal and managerial implication ... 51

6.3.1 Implications for SMIs ... 51

6.3.2 Implications for ecological industry ... 51

6.4 Limitation and suggestions for future research ... 52

vi

List of Figures, Tables and Figures and Abbreviations Figure

Figure 1 Themetic analysis ... 25

Figure 2 Data structure of IB gap in the ecological context ... 30

Figure 3 The impact of SMIs on consumers’ behavior ... 37

Figure 4: How SMIs moderate the Intention behavior gap ... 48

Tables Table 1 Interviewers’ description ... 23

Table 2 Subjective reasons of Intention – Behavior gap in green behavior adoption ... 34

Table 3 Objective reasons of Intention – Behavior gap in green behavior adoption ... 36

Table 4 The impact of social media influencers on consumers’ green behavior ... 37

Appendices Appendix 1: Semi-structured interview questions ... 68

Appendix 2: Interviewer behavior ... 71

Appendix 3 Data analysis for the IB gap in green lifestyle context ... 74

Appendix 4: Data analysis for the impact of SMIs on consumers’ green behavior ... 76

Abbreviations

IB gap: Intention-Behavior gap SMIs: Social Media Influencers IM: Influencer marketing

1

1 Introduction

This chapter provides a summary of the authors' intentions and expectations throughout the thesis. Firstly, information regarding the background and motivation of the research issues is given. Subsequently, from the identified gaps in previous studies, the research purpose and the research questions are proposed. Lastly, this section also mentions the delimitations, as well as the structure of the whole paper.

1.1 Background and motivation

In the recent 100 years, the world population has increased from 1.5 billion to 7.8 billion in 2020 (Brown & Flavin, 1999; Worldometers, 2020). Concurrently, developments have changed people's lives by making them more mobile and comfortable. Subsequently, to meet human requirements, people have created negative impacts on the environment. Some of the most critical environmental threats are worth outlined, that is ambient, water and air pollution, climate change, solid waste, and so forth (Ramlogan, 1997; World Health Organization (WHO), n.d-a; Environmental Protection Agency, 2020).

It can be easily perceived that environmental issues are directly having negative impacts on people's lives. WHO claimed that the world outdoor air pollution in both big cities and remote areas is estimated to cause 4.2 million premature deaths annually and climate change is forecast to cause roughly 250 000 new deaths per year in the 2030 - 2050 period (WHO, n.d-b). Hence, as argued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007), to effectively mitigate environmental issues, people need to adopt environmental-friendly actions. Recently, the environmental-friendly behaviors so-called 'green lifestyle' are being widely adopted among consumers in society (Chen and Chai, 2010) as people are aware that environmental issues can be more critical and adverse to their life. A green lifestyle can be understood as a way of life that aims at minimizing the negative effects on the environment (Pagiaslis & Krontalis, 2014). Thus, not only does it involve in purchasing environmental-friendly products, but it also consists of non-buying activities like simply bringing a reusable bottle or grocery bag, reducing as much as possible the amount of plastic consumption, limiting producing waste, recycling, reusing, and eating a meal plan of plant-based diet (Chwialkowska, 2019).

2

The researchers have pointed out that consumers who are aware of the environmental issues are more likely to get involved in green behavior adoption (Vernekar & Wadhwa, 2011; Khan & Kirmani, 2014; Steg et al., 2014; Coddington, 1990; Laroche et al., 2001; Cheah & Phau, 2011). However, there is still not a substantial portion of green consumers among all people. Empirical evidence suggested that while the numbers of consumers motivated by green consumerism values are considerable, a change in their behaviors is less apparent (Tang & Chan, 1998; Straughan & Roberts, 1999; Akehurst et al., 2012; Kumar, 2016; Futerra, 2005). As for non-buying behaviors, Green Industry Analysis (2017) reported that only 1 per 5 people who claim their awareness about the environment is willing to make an extra effort to change their daily habits to reduce the ecological negative impacts. In terms of purchasing actions, it was found that ecological intended consumers rarely make an actual ethical purchase (Auger & Devinney, 2007; Belk et al., 2005; Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Follows & Jobber, 2000). In general, environmentally friendly products account for only a small proportion of global demand; thus, the global market share for ecological products is estimated to be under four percent (United Nations Environment Programme, 2005). The phenomenon when consumers intend to do something, yet many of them fail to translate this intention into actions is academically called the intention-behavior gap (IB gap) (Faries, 2016). This topic is relatively contemporary in research and recently discovered in different contexts including technology usage (Bhattacherjee & Sanford, 2009), physical activities (Schwerdtfeger et at., 2012; Mohiyeddini et al., 2009), sustainable diet (Fink et al., 2018), healthcare actions (Allom et at., 2013), and so forth. As stated by researchers, the IB gap is contributed by plenty of factors, which are not the same in different fields. Regarding the green lifestyle context, the key discovered obstacles to green consumption are availability, price, insufficient awareness (Pagiaslis & Krontalis, 2014; White & Simpson 2013), lack of effectiveness, social bias, and feminization (Bennett & Williams, 2011; Brough et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the contributors of IB gap in green lifestyle, especially non-purchase behaviors found by researchers still stay sketchy and unsystematic.

As the following topic of IB gap, the subject "bridging the IB gap" also has a growing interest among researchers. In terms of ecological lifestyle, the study of Frank & Brock (2018) found out that communicating the advantages of organic groceries at the point of sale helped bridge the IB gap in purchasing organic groceries since the point of sale information emphasized trust and knowledge which can substantially diminish the informational and price barriers. Also, Fink et al., (2018) showed that external factors offering a wider variety of aspects

3

including advertising, pricing, and education contributed to closing the IB gap from the participants' view. Nevertheless, although the IB gap has long been studied, the topic of mitigating the IB gap has only been investigated in recent times. Thus, it remains poorly understood and given implications, especially within the present context of a green lifestyle. Together with the emergence of a green lifestyle, social media nowadays also becomes a crucial part of people's daily life as it plays an important role in spreading awareness of important information (Adewuyi & Adefemi, 2016). Wang et al. (2012) indicated that social media was a type of community through which people could acquire skills, knowledge, which are relevant to their function as consumers in the marketplace. The most influential power of social media is the electronic word of mouth (eWOM) through shares, comments, likes, posts, and conversations that users produce regularly (Phillips et al. 2013, p26; Talavera, 2015). Following the growth of social media, influencers marketing (IM) and social media influencers (SMIs), the social media users who have a voice to the others, are becoming a new trend in marketing and communication. The impacts of SMIs on consumer behavior has been found in different perspectives (Nurhandayani et al., 2019; Nguyen, 2018; Alkhathlan et al., 2019; Lisichkova & Othman, 2017). To be more specific, using SMIs becomes an effective marketing strategy to catch social media users' attention and trustworthiness by influencers' daily life sharing and recommendations (Kietzmann et al., 2011). Lisichkova & Othman (2017) argued that perceived authenticity, together with trustworthiness, credibility, legitimacy, honesty, and expertise of the influencers are the main features that have positive impacts on the consumers' behavior.

The effect of SMIs on consumer behavior has been investigated in several subjects including clothing, cosmetic products (Jensen, 2018; Sudha & Sheena, 2017), but yet not been explored in the context of green lifestyle. Yilmaz & Youngreen (2016) suggested SMIs spread knowledge and information, then urge new behavior adoption; which builds social media and SMIs a potential venue for promoting the green lifestyle. Li Ziqi, a Chinese eco-lifestyle mega SMI in the global market, owns more than 8.7 million international subscribers on YouTube (YouTube, n.d.) (despite YouTube is officially blocked in China) and more than 24.2 million followers on Sina Weibo (Weibo, n.d). She has a strong communication power in terms of ecological lifestyle to the audience, especially in the young generation by her videos, mainly about a healthy and ecological lifestyle in a rural area (Yan, 2019). Therefore, the authors assumed that the impacts on consumers' behavior of SMIs like Li Ziqi can diminish the IB gap in the context of green lifestyle adoption.

4

1.2 Purpose

As all the above-mentioned background information, the present study attempts to discover the impact of social media influencers in moderating the IB gap in green lifestyle adoption. To do that, the researchers aim to thoroughly understand the gap between what environmental intended consumers is about to do and what they do, and investigate how SMIs affect their behaviors to reduce this gap.

Firstly, despite excellent study on obstacles to purchasing ecological products; to date, not so many works comprehensively examined regarding non-purchase behaviors. Thus, the research on what drives people and what holds them back from adopting sustainable behaviors remains an understudied area. Secondly, since the previous studies focused mainly on barriers rather than influences, several researchers called for a better understanding of the factors which can drive their behaviors (Kotler, 2011; Goldstein et al., 2008). Finally, another study recommends future researchers exploring the relevance of social media and social media influencers in avocating green lifestyle adoption (Kumar, 2016), with the emphasis on how influencers help translate consumers' intention to behavioral adoption.

The investigation of social media influencers drives green lifestyle adoption and mitigates the IB gap which bears significant contributions. In terms of theoretical aspects, since the previous work about the ecological IB gap is mainly done on the purchase action, the recent study aims at contributing to the literature of the IB gap in general with exotic insights within non-purchase behaviors. Moreover, by understanding the impact of influencers on consumers, the present paper attempts to propose that using SMIs is a new and efficient method to decrease the IB gap. From the practical perspectives, the study intends to help ecological brands, especially the ecological product supply companies, build an appropriate marketing plan through carrying out further descriptive research from this initial one. Furthermore, as a positive outcome, not only could the results found in this paper help local ecological brands to explore opportunities on these two markets, but it might also provide the social media influencers with insightful information regarding how audiences perceive and value from them.

5

1.3 Research question

To achieve the research purposes of exploring IB gap contributors within the ecological context, as well as discovering how social media influencers influence consumers to minimize the IB gap, the following research questions are developed:

RQ1: Why do ecological intended consumers not to adopt ecological behaviors?

In consideration of previous research about IB gap (Pagiaslis & Krontalis 2014; White & Simpson 2013, Bennett & Williams, 2011; Brough, et al., 2016, Aertsens et al., 2009; Luchs, et al., 2010), the authors expect to explore possible obstacles that prevent ecological intended consumers from adopting purchase and non-purchase ecological behaviors.

RQ2: How do social media influencers moderate the intention - behavior gap within the ecological lifestyle context?

Further than discovering the contributors of IB gap, the authors attempt to understand how people who have a strong impact on social media can decrease this gap since SMIs are becoming a trend due to the growth in the use of social media from consumers (Edelmen, 2017). Therefore, the answer to this research question helps the readers to have insights of consumers in the consideration of social media influencers as a marketing channel.

1.4 Delimitations

To limit the scope and deepen the study, some information and perspectives have been disregarded. Firstly, although environmental problems are gaining more recognition from the public all around the globe, most of the research regarding consumers' environmental behaviors has been focusing on developed countries like the USA, the UK, and Europe. In contrast, study about Asian-based green marketing is relatively sparse (Lee, 2008). Therefore, the present research attempts to set the focus on the Asian market, specifically two countries, China and Vietnam due to the severe environmental issues in those countries. To be more specific, the most populous country China, passed the US to be the largest waste generator in the world in 2014 (Zhang et al., 2016). The World Bank estimated that Chinese urban citizens generate 1.02 kg waste per day in 2012 (Bhada-Tata & Hoornweg, 2012). Regarding Vietnam, as reported by World Air Quality Report, the capital city Hanoi is the 7th air polluted capital city in the world, 2nd in Southeast Asia, with the Air Quality Index being

6

46.9 (µg/m3) (IQAir, 2019). Furthermore, as the huge population in China and Vietnam which is 1,4 billion - rank 1 and 96,4 million - rank 15 in the world respectively (Statistic Times, 2019) and the living habit of collectivism in Asia (Cho, 2011), exploring and validating Asian consumers is potential to find valuable insights and suggestions for marketers and researchers to conduct further research. Besides, to have an insight into the Vietnamese and Chinese market, an in-depth interview technique is implemented in this paper. Due to time and financial restrictions as well as the severe situation of pandemic COVID-19, almost all interviews were conducted via online channels.

1.5 Thesis structure

This thesis is structured in 6 chapters. Chapter 1 reveals the background and motivation to conduct this study. From the given problem, the research questions will be proposed with purposes and intended contributions. Then Chapter 2 presents the literature review, with the aim of identifying relevant concepts within the topic. After that, chapter 3 explains the philosophy framing, and the research approach of this study, describes the chosen research design, approach to data collection, and the utilization of data collection techniques. Chapter 3 also discuss about the ethical considerations and the potential limitations in relation to the chosen methodology. Chapter 4 presents and analyzes the results from the collected data from an exploratory perspective. The in-depth discussion of given findings is found in Chapter 5 in relation to the research purpose, research questions, and previous findings. Chapter 5 also proposes the final framework which concludes and visualizes the above-mentioned findings and discussion. Finally, Chapter 6 concludes this thesis by presenting a general conclusion, the achieved contributions, main limitations, and rooms for the future research.

7

2 Literature Review

In this chapter, the literature review will be presented following three parts: Eco-lifestyle and Intention-behavior gap in this context, the relevance of social media influencers (SMIs) in ecological lifestyle, and the summary. The first part gives the readers the definition of ecological lifestyle, ecological consumers, and the previous work done in the topic IB gap. After that, the second part presents what has been studied in influencer marketing, who are the social media influencers; the research about the importance of IM and SMIs in affecting consumer behavior. Finally, the summary sums up the background and points out the study room for this research.

2.1 Eco-lifestyle and IB gap

2.1.1 Identify Ecological lifestyle and Ecological Consumers

2.1.1.1 Ecological lifestyle

‘Green lifestyle’ or ‘ecological lifestyle’ can be defined as a modern way of living to diminish as much as possible the negative impacts of humans on the environment, to effectively mitigate the alarming environmental issues (Chwialkowska, 2019). This term arose from the recognition of environmental degradation with notable issues including global warming, air and water pollution, acid rain, desertification, and so forth (Ramlogan, 1997). It can be easily noted that environmental issues are having negative impacts directly on people's lives with a dramatic increase in the number of deaths due to air pollution, hazardous waste, and climate change (WHO, n.d.; The Environmental Protection Agency, 2017). Many consumers, nowadays, start to exert an attraction towards environmental-friendly actions called ecological lifestyle after recognizing that environmental issues are becoming more critical (IPCC, 2007). This way of living is being widely adopted more commonly among consumers (Chen and Chai, 2010). Green lifestyle behavior involves purchasing environmental-friendly products (Pagiaslis & Krontalis, 2014) and non-buying activities like simply carrying a reusable coffee cup, grocery bag, reducing the amount of plastic (Chwialkowska, 2019). In terms of business, many firms have voluntarily adopted different actions that initiate ecological product innovation within their product development (Pickett-Baker and Ozaki,

8

2008). Thus, consumers also react with a positive perception and purchase their products (Sony et al., 2015).

2.1.1.2 Ecological consumers

‘Ecological intended consumers’ are people who feel a responsibility towards the environment and aim to express their values through consumption (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005), while ‘ecological consumers’ are defined as individuals who show actual daily behaviors which cause the least negative impact on the environment (Roberts, 1996). Hailes (2007) considered a green consumer as the one who combines the act of consuming green products following environmental preservation. Therefore, green consumers might have purchase behaviors (Pagiaslis & Krontalis, 2014) or the other non-purchase behaviors (Chwialkowska, 2019).

As for non-purchase behaviors, there are two main types of activities that a person has can be considered ecological or green lifestyle, that is avoiding using environmental-harmful products and protecting the environment through conservation activities (Hailes, 2007; Laroche et al., 2001; Pickett et al., 1995). Firstly, eco-lifestyle consumers often avoid buying products that they perceive as being harmful to their health and also the environment during production (e.g. made from ingredients coming from threatened habitats), usage and disposal (e.g. plastic-made products), energy consumption (e.g. petrol vehicles), and over packaging (Hailes, 2007). Secondly, ecological consumers also attempt to protect the environment by different conservation activities; for example: reusing, recycling, saving energy, planting trees, etc (Laroche et al., 2001). Pickett et al. (1995) created a scale focusing on conservation activity, which comprised numerous behaviors: disposition, recycling goods, being aware of packaging, saving the resources, etc. According to Pickett-Baker & Ozaki (2008), recycling is an environmental behavior that consumers engage with that most among all activities. In general, a person that can be considered as a green consumer will adopt at least one of these activities: carry a reusable coffee cup, bring a reusable grocery bag, reduce the amount of plastic use, limit produce waste, recycle and reuse, buy products locally, eat a plant-based diet (Chwialkowska, 2019) limit produced waste, recycle and reuse, buy products locally, eat a plant-based diet (Chwialkowska, 2019).

In terms of purchase behaviors, green consumers buy and use products that are not harmful to the environment (Sony et al., 2015). Green products include organic food, environmental-friendly cosmetics, sustainable consumer goods, ecological medicines, and even green

9

vehicles. Green purchasing emerges from beliefs about the personal and environmental benefits of green products (Bang et al., 2000; Jansson et al., 2010). In recent times, consumers are more conscious of health and environmental aspects, which makes them willing to pay a higher price for eco-friendly products (Cheah & Phau, 2011; Khan & Kirmani, 2015). A public opinion poll revealed that consumers indicated a preference for ecological products over normal ones when all other aspects are the same (Ginsberg & Bloom, 2004). Subsequently, a growing number of retailers and manufacturers are adapting to use environment attributes as a key point of product differentiation and development.

2.1.2 Intention-Behavior Gap

2.1.2.1 Intention and behavior relation

The intention is the instruction that people have to guide themselves to perform particular actions in certain ways (Triandis, 1980). Intention can be inferred from the personal answers in the form “I intend to do X”, “I plan to do X", or “I will do X” (Triandis, 1980). Specifically, in the eco-lifestyle context, the intention is the thought of consumers that can be “I plan to reduce the plastic consumption" or “I will try to save electricity". Behavior, whereas, is an action that occurred at the end of an individual's decision-making process (Ajzen, 1991). Bergner (2011), consider behavior as an attempt of the individual to bring about some state of an affair like by changing existing states. In the researching field, behavior can be regarded as an action a person does to contribute to environmental sustainability, which is discussed in part 2.1.1. The relationship between intention and behavior can be well explained that individuals’ behaviors are affected by their intentions to behave (Ajzen, 1991). For example, the intention to reduce plastic consumption leads to the behavior of bringing the clothing bags to replace plastic bags when the consumers are doing grocery shopping.

2.1.2.2 Intention Behavior gap

It was suggested by Ajzen (1985) that intention was the most important predictor of behavior. However, in 1991, this researcher acknowledged that people might not always have sufficient control over the execution of actions to achieve their intentions. The phenomenon when consumers intend to do an action, but many of them are unsuccessful to translate their intention into real action was called ‘Intention-Behavior gap’ (IB gap) or ‘word-deed gap’ (Faries, 2016; Sheeran, 2002, De Pelsmacker et al., 2005; Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Auger & Devinney, 2007). The IB gap has been widely studied in both the psychology and consumerism perspectives (Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Elliot & Jankel-Elliot, 2003). As for

10

consumerism perspectives, according to Auger & Devinney (2007); Carrigan & Attalla (2001), consumers do not walk their talk as many researchers believe, the explanation of which exists primarily in the way social desirability twists the measures of intention.

IB gap problems have stimulated researchers in different fields including physical exercise (Sniehotta et al., 2005; Rhodes & Dickau, 2012), ethical consumption (Hassan et al., 2016, Carrington et al., 2010), health and dietary (Kothe et al., 2015, Vanessa et al., 2013), technology usage (Bhattacherjee & Sanford, 2009). Specifically, data in health behavior research specified that intention predicted a mere 30% to 40% of the variation (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Rhodes & de Bruijn, 2013). In terms of physical activities, empirical evidence showed that the proportion of the participating population is relatively low (Dishman & Buckworth, 2001; Martinez-Gonzalez et al., 2001) and the increase in intended participants did not always lead to the rise in actual physical behavior (Milne, Orbell, & Sheeran, 2002). This IB gap was also found in IT usage research. Sheppard et al., (1988) illustrated that the average correlations between human intention and behavior were just around 0.58 in general. The gap between intention people possess and their overt behavior is generated by plenty of contributors. As suggested by Sheeran et al., (2005), barriers that control the behavior from intention go from the individual to the situational perspectives. Triandis (1980) pointed out that low facilitating conditions could prevent the performance of intended behavior. It was also argued by Triandis (1980) that certain behaviors are more likely to be controlled by habits than by conscious intention, the factor that is considered by researchers as the final section to perform activities. A more potent contributor to the IB gap derived from social psychology literature is the attitude strength (Krosnick & Petty, 1995; Pomerantz et al., 1995, Holland et al., 2002). This stream of the study suggested that people holding bolder attitudes toward the environment demonstrate a stronger association with their behavior, whereas those with lighter attitudes might have a weaker connection.

2.1.3 IB gap in eco lifestyle context

The intention – behavior gap has also been found in the consumption of society within the ecological purchasing context. In terms of purchasing behavior, intended ecological consumers infrequently translate into actual ethical purchasing at the cash register (Auger & Devinney, 2007; Belk et al., 2005; Carrigan & Attalla, 2001; Follows & Jobber, 2000; Shaw et al., 2007). For example, Bissonnette & Contento (2001) found in a survey of 651 students

11

that they had supportive attitudes to organic foods since they believed organic food was healthier, tastier, and beneficial to the environment. Yet their perceptions were not bold enough to encourage them to buy organic food regularly. Another study expressed that only 3% of the population purchase ethical products, while 30% of consumers claimed they would do (Futerra, 2005). As for non-buying behavior, a report by the RoperASW (2002) specified relatively disappointing results with environmental responsibility, that is, 59 percent of the population never thought of participating in environmental activities and only 1 in 5 environmental-aware individuals is ready to make an additional effort and alter daily habits to reduce the ecological footprint (Green Industry Analysis, 2017). Another study expressed that while 30% of consumers stated they would purchase ethically, only 3% did (Futerra, 2005). As for non-buying behavior, a report by the RoperASW (2002) specified somewhat disappointing results with overall environmental concern, that is 59 percent of the general population never thought of participating in environmentally friendly activities and only 1 in 5 environmental-aware individuals is willing to give an additional attempt and adjust daily habits to lessen the ecological footprint (Green Industry Analysis, 2017).

IB gap in eco-lifestyle purchasing and consumption has been a new and exciting topic for researchers to study for the last two decades (Follows & Jobber, 2000; Carrigan & Attala, 2001; Gupta & Ogden, 2006; Auger & Devinny, 2007; Carrington et al., 2010). Researchers have studied and found factors that cause the gap between behavior and intention in eco-lifestyle context, yet primarily in terms of purchase behavior.

Firstly, personal determinants include socio-economic characteristics like age, gender, education level, income, recognition, motivation, personal values and norms, habits, abilities to act; among those of which recognition, value, and habit have been considered as barriers to ecological behaviors (Carrington et al., 2010; Van de Velde et al., 2009; Tanner & Kast, 2003; Gollwitzer, 1999; Koths & Holl, 2012; Hughner et al., 2007). A study by Van de Velde et al., (2009) revealed that consumers’ consciousness had become a major factor for sustainable purchasing behavior. Similarly, according to the results of a survey by Tanner & Kast (2003), personal factors including beliefs about environmental values were required to advocate sustainable consumption of green products. Szmigin et al. (2009) used the term “cognitive dissonance”, which is the lack of ability to rationalize the purchasing behavior of eco-intended consumers, to call a factor coming from the recognition that facilitates the ecological IB gap. Moreover, Carrington et al. (2010) conceptually suggested the extent consumers translate their intentions into buying behavior depending upon their prior

12

planning. Therefore, the lack of planning can be called actual behavioral control which would lead to control over the buying experience (Carrington et al., 2010). Besides, the received information regarding the ecological field is also a huge contributor to the ecological IB gap since responsible consumers have a particular need for information (Koths & Holl, 2012; Hughner et al., 2007 ). The consumers who feel inadequately informed about the environmental issues, social performance of ecological lifestyle, and the emergence of eco products have a high ‘cognitive dissonance’, which later leads to mental pressure when choosing between normal and ecological products (Hughner et al., 2007). As a consequence, the more consumers feel overwhelmed by the volume of information communicated unofficially, the larger is the lack of transparency and trust (Koths & Holl, 2012).

Secondly, several situational barriers relating to the act of behaving including the purchase situation, as well as consumption options, have also been found by researchers (Zeng & Wei, 2007; Hughner et al., 2007; Chen, 2007; Zanoli, 2004; Honkanen et al., 2006). Many existing surveys on ecological consumption agreed that ecological products were more pricey than conventional products, which constituted the most important purchase barrier (Aertsens et al., 2009; Hassan et al., 2009). Specifically, in the Chinese market, consumers are willing to pay only 5–10% of the premium for green food if they get access to reliable information on green food (Zeng & Wei, 2007). Additionally, aspects of the buying environment were also mentioned by researchers. For example, the low consumption of green products is partly due to the lack of availability, when the products are not easy to discover on shelves and consumers have to buy in different places (Hughner et al., 2007) Convenience-oriented people usually avoid additional effort (Chen, 2007; Zanoli, 2004). Moreover, satisfaction with the quality of conventional goods and lacking additional benefits from organic products also prevent the purchase of consumers (Honkanen et al., 2006). As quality is one of the most important aspects to consider buying a product, consumers would tend to choose values in personal use rather than values in the environment when comparing normal and ecological goods. (Honkanen et al., 2006).

Finally, social factors covering societal norms relating to the cultural aspect, mass media in a region, as well as the situation in a social group, country, or region are also worth mentioning. For example, Chinese governments have made attempts to encourage citizens to consume green food and high-quality food. However, they still have been struggling with food safety issues by controlling soil contamination (Liu et al., 2012), pesticide residue (Shi, Lv, & Feng, 2011), and food processing (Zhou, Helen, & Liang, 2011).

13

In general, from all the above-mentioned information, the factors contributing to the IB gap in the eco-lifestyle context have been well understood in terms of purchase behavior. However, as for non-purchase activities as being described in part 2.1.1, it remains poorly investigated.

2.1.4 Bridging the IB gap

Similar to the IB gap, the topic of moderating the IB gap also has a growing interest among researchers in different contexts. Armitage & Conner (2001) illustrated that variables in the theory of planned behavior including attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control can partially bridge the IB gap. Besides, there has been much discourse on potential variables to moderate the IB gap, which is personality (MacCann et al., 2015; Monds et al., 2015), self- efficacy, action control (e.g. self- monitoring, effort) (Sniehotta et al., 2005), and planning or implementation intentions (Sniehotta et al., 2005; Reuter et al., 2008; Wieber et al., 2015). Milne et al. (2002) in research about bridging the IB gap in physical activity indicated that volitional power and motivational factors remarkably raised the likelihood to practice exercise. Furthermore, evidence has been found pointing out that self-regulation practices (Abraham, Sheeran, & Johnston, 1998) and perceived self-efficacy (Coumeya & McAuley, 1994; Estabrooks & Carron, 1998) can be used to describe the additional variance in affecting consumer behavior.

In the last decade, researchers started to study the approach to moderate the IB gap in terms of ecological lifestyle. For example, Frank & Brock (2018) found that communication at the point of sale helped bridge the gap between the consumers’ intention and their actual purchase to buy organic groceries. Category-specific and products’ environmental differentiation at the point of sale can emphasize the truthful knowledge, which substantially reduces the perception of informational and price barriers and changes behavior towards organic groceries (Frank & Brock, 2018). Further, Sultan et al. (2019) demonstrated the influence of perceived communication, satisfaction, and trust increased desirable behavior and reduced the gap in the intention-behavior relationships in the theory of planned behavior. Fink et al. (2018) showed that the higher number of external factors offers a wider diversity of aspects including advertising, pricing, and education that contribute to closing the intention-behavior gap from the consumers’ view.

14

2.2 The relevance of SMIs in consumer behavior

2.2.1 The importance of Influencer Marketing and Social Media Influencers

Nowadays, people are getting exposed to a social media world. The digital 2019 report (We Are Social, 2019) claimed there were 3.48 billion social media users by Jan 2019, 9 percent growth since 2018. Moreover, active users spend more than 2 hours daily on the most popular social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and so forth. The report also showed the specific data for each social media platform performance. For instance, Tik Tok, a Chinese social media platform company, has more than 800 million active users, 60% from China, and the rest from oversea countries like India, American, Vietnam (We Are Social, 2019).

2.2.1.1 Why influencer marketing is important to study?

According to Noor & Henricks (2011), social media is defined as powerful platforms to attract the target customer through creative content and strategies. Using social media platforms like YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Tik Tok, etc., become increasingly popular in business, to draw the target customers’ attention. Influencer marketing (IM) is also one of the trendiest and most dominant market strategies (Edelman, 2017). The most influential power of social media and influencer marketing is electric Word of Mouth (eWOM) (Liu et al, 2015). The eWOM exists everywhere; for example, in the interactions of users with their friends, families, even strangers through shares, comments, likes, posts, via Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, Tik Tok, etc.

As influencer marketing has become a channel to the business, several successful research regarding IM has been carried out in terms of clothing, cosmetic products. For example, in the beauty industry, influencer marketing can help brands to reach the new target consumer groups efficiently since the strong impact on eWOM contribute coniderably to the brand’s reputation (Jensen, 2018). In the field of fashion, researchers also proved that personal blogs affect young women purchasing behaviors significantly through bloggers’ positive comments, as female consumers enjoy having a reliable source telling them opinions on the products and trust texts by someone they like (Sudha & Sheena, 2017).

15 2.2.1.2 Who are Social Media Influencers?

Social Media Influencers (SMIs) are the users who have a big voice to the others in the digital world. Ogilvy (2017) classified social media influencers into 3 main types: traditional mass awareness influencers (celebrities, etc.), digital and micro influences (YouTubers, Instagrammers, etc.), and consumer-driven brand advocates (consumer advocates, etc.). With different perspectives, Edelman (2017) suggested classifying SMIs in 2 categories: Mass influencers and Micro influencers, based on the followers’ size. The former group has more than one million followers/subscribers on social media platforms, whereas the later have less than this number of fans. The brands and companies can consider to choose the most suitable SMIs to collaborate with, in order to gain the best performance.

In terms of the ecological lifestyle context, there is a growing number of social media users who are creating and shareing attractive and informative content on their channels. Their information spreads out among the digital society and their names become well-known day by day. For instance, Li Ziqi is one of the most successful SMIs in China in the research context. She is a Chinese eco-lifestyle mega SMIs in the global market who owns more than 8.7 million international subscribers on YouTube (YouTube, n.d.) (despite the fact that YouTube is officially blocked in China) and more than 24.2 million followers on Sina Weibo (Weibo, n.d.). She has a powerful communication impact in terms of ecological lifestyle to the audiences, especially the young generation. Her video content is primarily about a healthy and ecological lifestyle in a rural area in China. She shares to the audience a self-sufficient and laid-back life in a rural area with breath-taking nature and also Chinese ancient traditions. Thus, she receives a huge amount of positive responses from followers on social media. On the other hand, in the Vietnamese market, Giang oi and Helly Tong are also worth mentioning as successful SMI advocating green lifestyle. They are all promoting the sustainable and positive way of living of a modern citizen and also having a huge influence on the young generation in this country. Based on above-mentioned information, the authors realized the significance to examine eco-SMIs as a new and efficient way to drive the followers’ green behaviors to contribute to the ecological industry.

2.2.2 SMIs and Consumer behavior

Consumer behavior is a topic about how consumers act to meet their needs including engaging, purchase intention, evaluating, buying, using, and the process of decision making

16

(Engel et al., 1986; Schiffman & Wisenblit, 2015). Many researchers have investigated the importance of IM & SMIs and how SMIs impact the consumers from different perspectives, such as the connection to customers’ intention, behavior, brand recognition, etc. (Nurhandayani, Syarief & Najib, 2019; Nguyen, 2018; Alkhathlan, Alotaibi, & Saad, 2019; Lisichkova & Othman, 2017).

2.2.2.1 How SMIs impact on consumers’ intention

It was found by researchers that SMIs in IM are the keys to address the messages to the audiences. Nurhandayani, Syarief, & Najib (2019) claimed SMIs contribute to the consumers’ intention in a positive correlation. Using SMIs becomes a strategy or channel that can catch social media users’ more attention and trustworthiness, especially by influencers’ daily life sharing or recommendations (Kietzmann et al, 2011). The factors regarding influencers and their impacts on consumers’ intentions have been explored. Lisichkova and Othman (2017) found out that SMIs impact on consumers’ online purchase intention positively based on the main features such as perceived authenticity, together with trustworthiness, credibility, legitimacy, the expertise of the influencers and their honesty.

2.2.2.2 How SMIs impact on consumers’ behavior

Regarding how the audiences’ behaviors are influenced by SMIs, Zhu & Chen (2015) pointed out the self-esteem could affect the decision-making process, that is, emulating or copying the SMIs’ styles (e.g.: buy same clothes, bags, shoes; visit same places; have the same lifestyle.), for instance. Forbes (2013) found a surprising result that social media users would not consider the KOLs’ recommendations when they buy an in expensive item. They also suggested that future studies to do with the market outside the United States and with a more specific type of product. Hu, Zhang, & Wang (2019) proved that SMIs can increase the consumers’ trust in the adoption of the applications including structural assurance, download volume, and online ratings positively.

2.2.2.3 How SMIs moderate the IB gap

In order to study transferring the intention to the actual behaviors, Lou and Yuan (2019) tested with a model to investigate six effect components for SMIs that make messages trustworthiness. Balaban and Mustatea (2019) found similar results about the credibility of the SMIs in Romania and Germany. Furthermore, some researchers also proposed the strategies and authenticity management framework to help SMIs manage authenticity to

17

resolve the tension trust from followers and build a win-win relationship with the brand or partner (Audrezet, Kerviler, & Moulard, 2018). In the term of the ecological lifestyle context, based on the minority influence model and social learning theory, Chwialkowska (2019) explored how sustainable lifestyle influencers drive the green lifestyle adoption and map the process of behavior change.

2.3 Summary

Firstly, previous research about IB gap in ecological behavior context has well investigated in terms of buying behavior of green products like organic food (Fink et al., 2018), greengrocery goods (Frank & Brock, 2018), ethical products (Carrington et al., 2010). However, to date, little is known on the IB gap regarding non-purchase behaviors including information sharing, disposal, recycling, and reusing. Thus, the research on what holds people back to have a green lifestyle remains an understudied topic and demands for further investigation (Kotler, 2011, Goldstein, et al., 2008, Mick, 2006)

Secondly, the promotion of ecological lifestyle and green products is relatively a novel topic in the field of influencer marketing. Nguyen (2018) suggested future research examining the impacts of SMIs on their followers in different industries. There have been several studies (Lou & Yuan, 2019; Balaban & Mustatea, 2019; Audrezet, Kerviler, & Moulard, 2018) stated several methods to bridge the IB gap, that is increasing the SMIs’ content credibility and trustworthiness. However, In the context of the green lifestyle, there are not so many researchers who have done a specific study about how SMIs moderate the consumers’ ecological lifestyle IB gap. Chwialkowska (2019) conducted a study focusing on the SMIs’ informational and normative influence and explored how SMIs communicate and drive green lifestyle adoption. This research provided a steady foundation for the authors to understand more deeply how SMIs encourage followers to adopt green behaviors and mitigate the IB gap.

In sum, various theoretical perspectives are providing the foundation for supposing that the impact of social media influencers as a mediator of intention – behavior gap, which can contribute to significant growth in the actual behaviors in ecological behavior adoption. The research of Chwialkowska (2019) identified the several key features of social media communication driving green lifestyle adoption, which is informational and normative influence, which might be a potential approach in mitigating the IB gap to green behavior

18

adoption. From these considerations, the authors conducted an exploratory study intending to find more possible factors contributing to the IB gap in non-purchase green behavior and investigate how the gap between intention and behavior in this context is diminished with social media influencers were included as a mediator.

19

3 Methodology

This chapter attempts to explain the methodological aspects assosicated to the research purpose. Firstly, the authors describe the research philosophy and elaborate on the reasons of choosing the the constructivism paradigm. Secondly, the authors continue to clarify the exploratory nature of the current study and why the inductive approach is chosen. The use of qualitative semi-structured interviews is also outlined and described. Thirdly, the authors comprehensively point out the main steps to analyse data using the inductive approach. Finally, the ethical considerations and quality of the research are futher discussed.

3.1 Research approach 3.1.1 Research philosophy

In order to conduct a successful study, establishing a appropriate philosophical standpoint for the researchers is necessary. In other words, the way researchers view the world will shape the study. The ontological, epistemological, and methodological assumptions as paradigms enable researchers to state viewpoints and guide study (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Therefore, the type of paradigms must be selected appropriately and contributed to the research purpose. Understanding what ontological and epistemological assumptions is could improve the quality of the research (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson & Jaspersen, 2018). Ontology helps scholars to find what constitutes reality, while epistemology assists researchers to understand how people know that that is a reality (Bryman, 2012; Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

The ontology is to consider the constitution of reality with has two types, that is realism and relativism. Epistemological beliefs are decided by ontological beliefs. Relativists hold the belief in different versions of reality since it is established by the way people see things and it develops and changes by people’s experiences (Killam, 2013). Relativism can be utilized as subjective measurements to interpret the reality shaped by a context and applied in the similar contexts. In this study, the authors attempt to explore the consumers’ perception of the IB gap in ecological context and how SMIs moderate the IB gap and urge consumers to adopt a green lifestyle involving both purchase and non-purchase behaviors. Hence, relativism with a subjective view is appropriate for the research purpose. After the authors showing ontology and epistemology of this study, the constructivism paradigm is conducted for this research,

20

which supports the researchers to explore the multiple realities and discover the underlying meanings by interpreting the knowledge (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). The constructivism paradigm helps the authors gain an in-depth understanding of how SMIs diminish the IB gap in the ecological lifestyle context by exploring participants’ perspectives of realities within their experiences.

The methodology is chosen based on ontological and epistemological beliefs. Qualitative approach is considered to be appropriated. Qualitative research supports researchers to interpret the data in a natural setting and have an insight into the phenomena (Ospina, 2004). In accordance with the qualitative methodology, this study aims to understand and gain an intensive overview of the IB gap and how social media influencers bridge this gap in the ecological lifestyle context. In line with the qualitative research, an inductive approach is chosen to analyze from data to theories, from a specific observation to a general and logical conclusion. Although induction has a problem that people cannot expect the future to like the past, it is still a useful way to know the truth or experience from the past and contribute to the future more or less. The researchers can understand clearly about participants’ thoughts and actions and will conclude logically how social media influencers bridge the IB gap in an ecological context.

3.1.2 Research design

The purpose of the research design is to structure the research activities, select the right sample, collect and analyze data reasonably, and accomplish the research purpose (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Based on the research purpose, each research can be classifed into three different types: exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory study (Saunders et al., 2016). According to Saunders et al. (2016), the explanatory research is conducted to explain the relationship between cause and effect of variables. Descriptive research, in the other hand, is utilized to give definition to a viewpoint, perception, and behavior that are held by a group of people; or a certain subject. Finally, the exploratory research aims to discover specific ideas and insights from the data. Because this study aims to gain an in-depth understanding of the IB gap and how social media influencers can bridge this gap in an ecological lifestyle context, descriptive or explanatory research is not considered appropriate. Furthermore, exploratory research also aims to develop and creates new knowledge (Saunders et al., 2016). Hence, an exploratory research design will be conducted.

21

Based on the study purpose the researches formulated two research questions (why and how questions) and aligned with the philosophical standpoints and the exploratory research design, a qualitative study will be conducted. The sources of information for this research are the primary data through the semi-structured interview to collect. In order to fit the schedule and costs of the research, snowball sampling will be executed. Due to fulfilling the research question, the collected data were analyzed using the thematic analysis method, which is commonly utilized for qualitative data (Thomas, 2006). In the below section, the researchers will discuss the process of data collection, data analysis, and also consider about ethical issues and reseach quality.

3.2 Data collection

3.2.1 Semi-structured interviews

According to Myers (2013), interviews, observation, and fieldwork are the three most common type used by researchers for collecting data in qualitative research. Among these three, interviews are the most widely used techniques, by which the researcher can gain various data from people in different roles, settings, and background biography (Myers, 2013). The interview method makes use of a specific guidelines of questions to explore the research topics and in-depth experiences from interviewers (Charmaz, 2014). The recent study aims to understand and gain an intensive overview of the IB gap and how social media influencers can bridge this gap in the ecological lifestyle context. Thus, interviews is the most relevant method of data collection for the researchers to apply in the present research.

The interview method consists of three different types classified by the structure, that is highly structured, semi-structured, and unstructured interviews (Easterby-Smith et al., 2013; Myers, 2013). Saunders et al. (2009) indicated that exploratory research requires the flexibility in data collection; thus, it is more effective for researchers to utilized semi-structured or unstructured interviews. These two types can help to gather more open answers, compared to the other type. Furthermore, according to Easterby-Smith et al. (2018), a semi-structured interview permits consistency and structure through pre-formulated questions while allowing flexibility and adaptation in each of meetings with individual participants. Considering the purpose of getting new insights, unfold new dimensions about IB gap as well as the influence of SMIs in an ecological context, the researchers choose semi-structured interviews as the most suitable method to conduct.

22

3.2.2 Sampling

The sampling technique in research is divided into two main, that is probability and non-probability (Saunders et al., 2009). Probability technique can minimize the sampling errors since it gives all people in the whole population a chance to be selected, while non-probability technique might cause sampling errors as it selects samples for a specific purpose with a predetermined purpose of selection (Babin & Zikmund, 2016). In research in the field of marketing, the non-probability sampling technique is more preferable for researchers as in this field it is not possible to obtain an overall list that is completely suitable for the particular purpose of the researcher (Saunders et al., 2009). In the present study, the non-probability technique is the most suitable due to the initial approach of exploratory research. This approach requires an in-depth analysis and relatively small sample size is acceptable. Thus, actively choosing appropriate participants based on researchers’ consideration is efficient to achieve the study purpose (Babin & Zikmund, 2016; Saunders et al., 2009). To be more specific, since ecological life is a relatively new term especially in the delimitation market, the use of non-probability sampling techniques can enable the authors to reach interviewees who already have an idea about the topic. Nevertheless, to minimize the potential risk of subjectivity and prejudice, the authors as the roles of interviewers, attempt to avoid interrupting the informants when they are sharing their experiences and ideas during the semi-structured in-depth interview.

Saunders et al. (2009) classified non-probability sampling into four main types so-called quota, purposive, volunteer, and haphazard sampling. For the current study, due to the restricted timeline and resources, volunteer sampling was chosen to collect primary data, since it enables the authors to choose interviewees who already have certain experiences in the research topic. Furthermore, snowball sampling is a technique in which existing subjects provide recommendations to recruit samples needed for a research study (Saunders et al., 2009). In fact, for a contemporary research field like eco-lifestyle, there are not so many people who are able and willing to expose their own feelings and perceptions (Yin, 2011). At first, the authors selected several interviewees who consider themselves as “partly green consumers” and know some influencers in this field to participate in the research. After finishing these data collecting sessions with the first interviewees, they were asked to connect the authors with the additional participants who are also suitable the requirements of this study. The process of selecting samples came to the end with 10 participants (Table 1).

23

Certain criteria considered from the literature review was established to select the most suitable participants, which ultimately enable researchers to get rich, relevant, reliable, and data for the analysis. The criteria were as following:

- Consumers who consider themselves having some behaviors of ecological lifestyle. - Consumers who use social media a few hours daily.

- Consumers who are aware of influencers in general and ecological influencers in specific.

Participant

Number Country Information Personal Interview Date Interview Length

P1 Vietnam 23 Salesperson March 17th 53m08s

P2 Vietnam 23 Content Marketing March 17th 67m03s

P3 Vietnam 29 Book Editor March 15th 74m03s

P4 Vietnam 25 Auditor March 15th 63m08s

P5 Vietnam 22 Salesperson March 16th 59m06s

P6 China 28 Banker March 13th 56m56s

P7 China 30 Civil servant March 14th 68m59s

P8 China 30 IT engineer March 15th 128m48s

P9 China 30 IT Manager March 28th 39m40s

P10 China 20 Student April 13th 47m44s

Table 1 Interviewers’ description

3.2.3 Interview guide and structure

Before collecting data, the interview guides and structure were created. As indicated by Esterby-Smith et al. (2018), there are three main features a researcher should take into consideration when designing a semi-structured interview, which is also incorporated in the recent study. Firstly, it is crucial to formulate open-ended questions to encourage participants to reflect on their experiences. Secondly, researchers should expand stories around the topic

24

to keep conversation flow naturally. Lastly, to create a shared understanding, the clarification of any complex concepts used (e.g. ecological, social media influencers, etc.) would be given to participants. Additionally, to keep the interviews going steadily, researchers decided to divide the guide into five different parts: formalities, background information, intention towards green lifestyle, behavior toward lifestyle and perception toward ecological SMIs (Appendix 1). The formalities part is used to generate background understanding of the current research by providing interviewees the study purposes as well as defining the main concepts of ecological lifestyle, IB gap, and influencers. Then, the personal information of interviewees is collected. After that, the interviewers move to the intention and behavior towards the ecological lifestyle part to interpret their barriers toward the ecological lifestyle. To avoid being excessively academic, ‘icebreaker’ questions around the topic are provided before diving into details. Finally, the topic of influencers and their impact on followers is added to close the topic. General questions are asked following by the follow-up questions as ‘probing’ techniques (Esterby-Smith et al., 2018) to extract further information (e.g., Can you please explain more about what you said?, What do you mean by that?, etc.).

3.3 Data analysis

3.3.1 Interview summary

The researchers conducted ten different interviews with so-called “green considered consumers” (Table 1). In total, around 12 hours of data were collected with the semi-structured interviews, all of which were done via video calls. Besides taking highlighted information throughout the interviews, all information was also fully recorded with recording application in smartphones. After conducting each interview, the interviewers made comprehensive summaries by reviewing noted information and re-listening to the recording audio to take out the most standout and relevant information for the analysis part.

3.3.2 Analysis method

The gathered data were analyzed by thematic analysis method, an inductive method which can be applied within both realist and social constructionist approach (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). It is utilized for a multiple types of data including written, verbal, and so forth. Saunders et al. (2009) stated that thematic analysis helped researchers to investigate multiple categories from the transcription of interviews. Additionally, it also contributes to the general and specific discussion as the researchers can group information into different defined

25

themes that contribute to the key findings(Saunders et al., 2009). In the thematic analysis method, the categories are come up by researchers from the development of different codes. These themes are significant enough to explore and explain a research phenomenon and ultimately to give answers to the stated research questions and purpose. By incorporating this type of data analysis, the analysis would express a convincing and systematic insights about the data collected and the research topic (Braun & Clark, 2008).

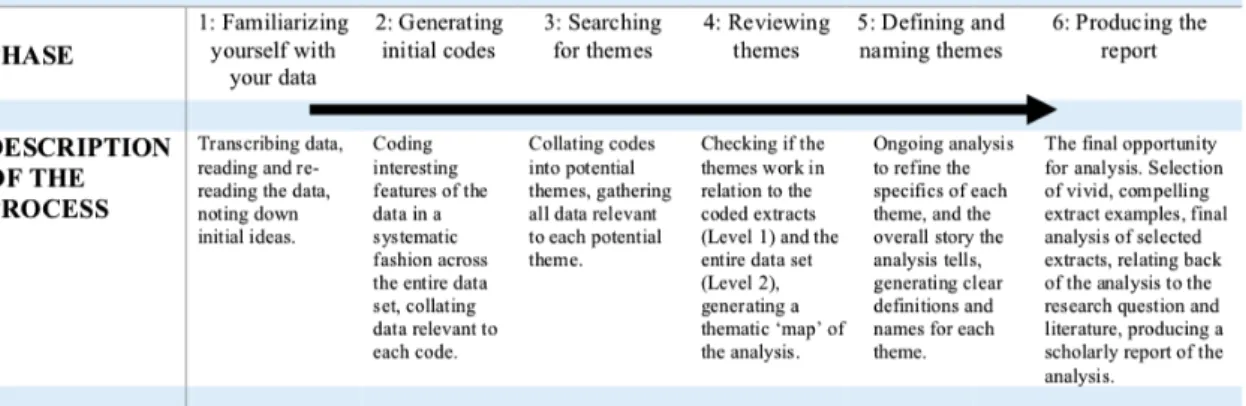

Figure 1 Themetic analysis (Source: Braun & Clark, 2008)

As suggested by Braun & Clark (2008), the chosen method consists of six different steps (Figure 1): the authors familiarize themselves with the data, then generate general codes, discover for themes, review these proposed themes, define themes name, and finally put all the report. In the present research, initially (1st step), the data in the interviews was transcribed from the recorded audios and become a solid foundation for the following analysis. Initial notes were taken based on the research purpose and research question. In line with the inductive approach and exploratory purpose, data were collected as ‘an empty sheet’ for the authors to re-read and individually produced first-level codes across the entire data set. In the 2nd step, initial codes were generated by grouping similar ideas and assigning them into themes accordingly to its characteristics, the core meanings of which were assured to be maintained. When it comes to exploring themes (3rd step), the analysis was done in consort with the second steps where the researchers searched for themes and allocated each characteristic into the right categories. Also, themes were presented with the most interesting and relevant parts of the interview. It is noticeable that the first three steps were done individually with the expectation to find different aspects from collected data. After the authors did coding for characteristics and came up with the ideas of the possible themes, all results were combined to create themes. After that, the findings and analysis are reviewed