Lean Startup as a Tool for Digital

Business Model Innovation: Enablers and

Barriers for Established Companies

MASTER THESIS

THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 credits PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Digital Business AUTHOR: Maja Beisheim and Charline Langner JÖNKÖPING May 2021

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Lean Startup as a Tool for Digital Business Model Innovation: Enablers and Barriers for Established Companies

Authors: Maja Beisheim and Charline Langner Tutor: Henry Nelson Lopez Vega

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Lean Startup, Digital Business Model Innovation, Business Models, Business Experimentation, Established Companies, Agile Methods.

Abstract

Background: The rapidly changing world of digital technologies forces many companies to

undertake a digital shift by transforming existing business models into digital business models to achieve sustainable value creation and value capture. Especially, for established companies, that have been successful leaders before the dot-com bubble (1995-2000) and whose business models have been threatened by the emergence of digital technologies, there is a need for a digital shift. We refer to this digitization of business models as digital business model innovation. However, often adoption and implementation of digital technologies require tremendous changes and thus, can be challenging for established companies. Therefore, agile methods and business experimentation have become important strategic elements and are used to generate and test novel business models in a fast manner. We introduce lean startup as an agile method for digital business model innovation, which has proven to be successful in digital entrepreneurship. Thus, it requires further empirical investigation on how to use lean startup in established companies for successful digital business model innovation.

Purpose: The purpose of our study is to identify enablers and barriers of lean startup as a tool

for digital BMI in established companies. Thus, we propose a framework showing how established companies can be successful in digital business model innovation by using lean startup.

Method: We conducted an exploratory, qualitative research based on grounded theory

following an abductive approach. Using a non-probability, purposive sampling strategy, we gathered our empirical data through ten semi-structured interviews with experts in lean startup and digital business model innovation, working in or with established companies, shifting their business model towards a digital business model. By using grounded analysis, we gained an in-depth understanding of how lean startup is used in practice as well as occurring barriers and enablers for established companies.

Conclusion: We emphasize that successful use of lean startup for digital business model

innovation is based on an effective (1) lean startup management, appropriate (2) organizational structures, fitting (3) culture, and dedicated (4) corporate governance, which all require and are based on solid (5) methodical competence of the entire organization. Furthermore, (6) external influences such as market conditions, role of competition, or governance rules indirectly affect using lean startup as a tool for digital business model innovation.

Table of content

List of Figures ... iv List of Tables ... iv List of Abbreviations ... iv 1. Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem discussion ... 31.3 Research question and research purpose ... 3

1.4 Outline of the paper ... 4

2. Literature Review ... 5

2.1 Business Model Innovation ... 5

2.1.1 Business Models ... 5

2.1.2 The digital shift – Business Models and Digital Technologies ... 6

2.1.3 Digital Business Model Innovation ... 8

2.2 Lean Startup as a Tool for Digital Business Model Innovation ... 9

2.2.1 Business Experimentation and Lean Startup... 10

2.2.2 Lean Startup ... 10

2.2.3 Digital Business Model Innovation with Lean Startup in Established Companies ... 15 3. Methodology ... 17 3.1 Research Philosophy ... 17 3.2 Research Approach ... 18 3.3 Research Design ... 19 3.3.1 Data Collection... 19 3.3.2 Sampling Strategy ... 21 3.3.3 Interview Design ... 22 3.4 Data Analysis ... 24

3.5 Research Ethics and Quality Insurance ... 27

4. Empirical Findings ... 31

4.1 Lean Startup Management ... 34

4.1.1 Agility ... 34

4.1.2 Digital Tools ... 35

4.1.3 Handling of Hypotheses ... 35

4.1.4 Handling of Minimum Viable Product ... 36

4.1.5 Customer Involvement ... 37 4.2 Organizational Structures ... 38 4.3 Culture ... 40 4.3.1 Corporate Culture ... 40 4.3.2 Mindset ... 41 4.3.3 Personal Culture ... 42 4.3.4 Motivation ... 42 4.4 Corporate Governance ... 43 4.4.1 Management ... 43 4.4.2 Leadership ... 44 4.5 Methodical Competence ... 46 4.5.1 Knowledge ... 46

4.5.3 Teaming... 47

4.6 External Influences ... 48

5. Analysis ... 50

5.1 Framework of Enablers and Barriers for Lean Startup ... 50

5.2 Digital Business Model Innovation with Lean Startup in Established Companies ... 52

5.2.1 External Influences... 52

5.2.2 Methodical competence ... 53

5.2.3 Organizational Structures, Culture, and Corporate Governance ... 54

5.2.4 Lean Startup Management ... 56

6. Conclusion & Discussion ... 58

6.1 Summary ... 58

6.2 Theoretical Implications ... 59

6.3 Managerial Implications ... 60

6.4 Limitations and Future Research ... 62

Reference list ... 64

List of Figures

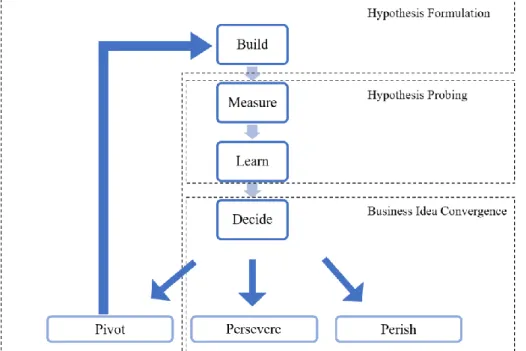

Figure 1: Lean startup hypothesis process (Eisenmann et al., 2012). ... 12

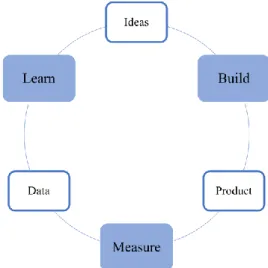

Figure 2: Build-Measure-Learn loop (Ries, 2011). ... 13

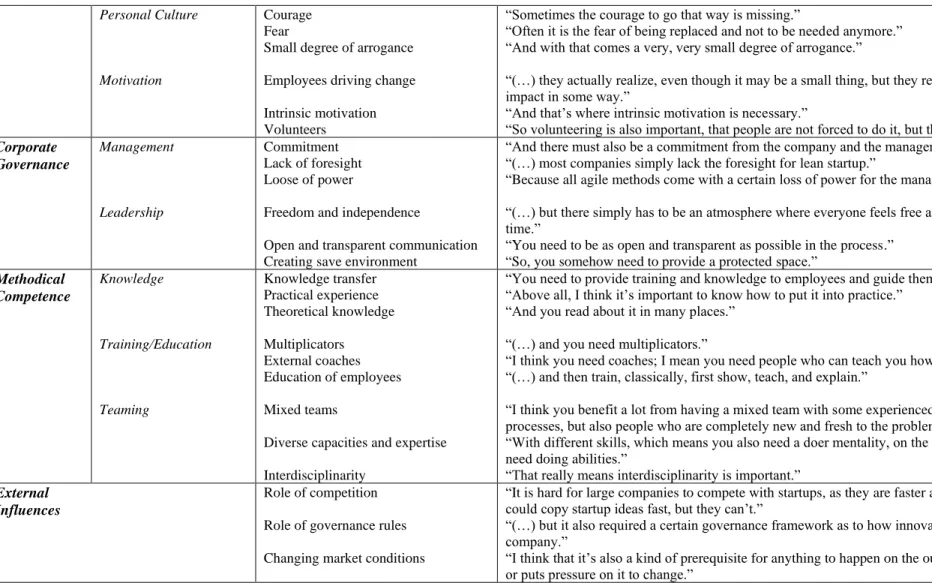

Figure 3: Final coding tree with example codes. ... 26

Figure 4: Enablers and barriers for using lean startup as a tool for digital BMI. ... 50

List of Tables Table 1: Overview of Interview Partners. ... 20

Table 2: Overview of categories and sub-categories with example codes and quotes. .. 33

List of Abbreviations

BM Business Model

BMI Business Model Innovation MVP Minimal Viable Product

1. Introduction

___________________________________________________________________________

This thesis examines lean startup as a tool for digital business model innovation in established companies. The purpose of this part is to familiarize the reader with the research field by introducing and bridging the main topics of business models and business model innovation with digital technologies and lean startup. Further, it discusses the problem statement and identifies research gaps, leading to the purpose and research question of this study.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

Every company explicitly or implicitly operates with a business model (BM), predicting what customers want and need (Teece, 2010), describing how companies create and deliver value, identifying customers and how companies engage with them (Amit & Zott, 2012a; Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Teece, 2010). To achieve sustainable value creation and value capture as well as customer satisfaction, companies are required to continuously question and rethink their BM to stay competitive (Achtenhagen et al., 2013; Amit & Zott, 2012b). Especially, digital technologies have revolutionized how industries operate and how value is created and captured in businesses (Dal Mas et al., 2020). This led to a transformation of business structures and activities and requires companies to make organizational-wide changes (Brynjolfsson & Hitt, 2000).

The rapidly changing world of digital technologies empowers the digitization of products and processes and forces many companies to follow that digital shift to keep up with the competition and to fulfill customer and market needs (Chanias et al., 2019). Over the past years, new technologies changed the nature of products and services, customer relationship management, organizational structures, business operations, and even whole BMs (Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Chanias et al., 2019; Correani et al., 2020; Rachinger et al., 2019; Westerman & Bonnet, 2015). Thus, there is a need for companies to reinvent themselves to successfully adopt digital technologies. However, besides opportunities such as increased flexibility, reactivity, and product individualization, the digital shift also presents challenges such as the complexity of using and implementing technology or changing customer behavior and preferences, as well as legal requirements (Rachinger et al., 2019). For this study, we focus on a digital shift in the context of business model innovation (BMI), caused by the adaptation and implementation of digital technologies. Often, existing BMs are successful for a certain time period but need to be adapted to new market conditions, forced by digital technologies, and if not, they risk failing

Charline Langner (Achtenhagen et al., 2013). Therefore, BMI can be a powerful tool as it provides potential for new products and services, and new markets (Amit & Zott, 2012b). In this context, digital technologies are a facilitator of BMI which can either force BMs to change completely, by replacing old ones, or they can advance value creation and delivery by extending existing BMs (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013). Thus, adapting digital technologies shifts existing BMs towards digital BMs. Therefore, we define digitization of BMs as digital BMI.

Especially established companies whose BMs have been threatened by the emergence of digital technologies (Chanias et al., 2019), require a digital shift (Ross et al., 2016; Sebastian et al., 2017). These companies have often been established leaders before the dotcom bubble (1995-2000) and thus, experienced rather low competition and steady success. Mainly, these established companies belong to traditional industries, such as finance, retail or automotive. Often, their original BM does not include digital components and hence, is not prepared for today’s competition (Ross et al., 2016). A good example of an established company, shifting its BMs by adapting digital technologies, is Philips Lightning, as it moved from selling light bulbs, electricity, and installations to selling lights as a service on a pay-per-use basis (Tekic & Koroteev, 2019). In comparison to so-called born-digital companies which started in the digital era such as Google, Amazon, or Facebook, established companies need to make tremendous changes when adopting and implementing digital technologies (Ross et al., 2016). In most cases, their processes, organizational structures, or BMs are not designed for adapting novel digital technologies (Chanias et al., 2019). The challenge for these established companies is to reinvent their BMs and to adopt digital technologies as well as to make strategic changes, while simultaneously taking advantage of their well-established business and maintaining their customer relationships (Sebastian et al., 2017). Many traditional companies are too slow and cautious in transforming processes (Westerman & Bonnet, 2015). Also, established companies often perceive digitization as a challenge rather than an opportunity for change.

Therefore, agile methods and business experimentation have become important strategic elements. They are used to generate and test novel BMs in a fast manner (Bocken & Snihur, 2020). One of these agile methods within the context of business experimentation is lean startup (Ries, 2011). This method is a customer-centric approach aiming to identify the preferences and needs of customers through feedback loops and step-by-step adjustments of products and services. Lean startup has mainly been investigated for BMI within digital entrepreneurship

(Ghezzi, 2020; Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2020). Also, it has proven to be an agile, innovative, and successful method to facilitate change processes (Balocco et al., 2019). Yet, research has not examined how lean startup can be successfully used as a tool for digital BMI in established companies.

1.2 Problem discussion

In comparison to the dynamic environment of startups, established companies need to undertake tremendous changes to shift from a traditional business to the digital economy (Ross et al., 2016). Still, many of these large enterprises are in an early stage of adopting and implementing digital technologies (Sebastian et al., 2017). Often, established companies lack organizational structures and capabilities to make fast decisions and hence, have difficulties transforming (Ross et al., 2016). Over the past years, the agile approach of business experimentation became an emerging topic in BMI (Bocken & Snihur, 2020). However, this approach is mainly used in startups and entrepreneurial contexts, given the dynamic and fast-changing environment. In line with these business experimentations, agile methods are gaining more and more interest not only for startups but also for established leaders. However, established companies seem to struggle with adapting to the new, agile, and experimental work environment and fail to implement methods like lean startup (Bocken & Snihur, 2020). Still, academic understanding of lean startup is only emerging (Bocken & Snihur, 2020). Thus, it needs further investigation to enrich current theory and discover enabling and hindering factors for applying lean startup in established companies. As lean startup has proven to be a successful tool for BMI in (digital) startups, we aim to identify success factors for established companies.

1.3 Research question and research purpose

The purpose of our study is to identify enablers and barriers of lean startup as a tool for digital BMI in established companies. By doing so, we aim to propose a framework showing how established companies can be successful in digital BMI using lean startup. Thus, the research question which shall be explored is:

What are enablers and barriers of lean startup as a tool for digital business model innovation?

To answer our research question and to build our framework, we conducted semi-structured interviews with experts in lean startup and digital BMI, working in or with established

Charline Langner companies that are shifting towards a digital BM. By doing so, we gained an in-depth understanding of occurring barriers and enablers for lean startup in established companies given our diverse interview partners. We identified internal and external factors facilitating and hindering lean startup in established companies. Also, we outline necessary organizational changes required to succeed in digital BMI with lean startup. Our study contributes to current theory of agile methods and lean startup, BM, and BMI. Thus, we combine lean startup and BMI, specifically digital BMI, by investigating lean startup as a tool for digital BMI and extending it to established companies. Further, we provide practical implications on how such companies can use lean startup or what to consider when already working with the approach.

1.4 Outline of the paper

The thesis is structured as followed. In chapter 2, the study’s theoretical background is outlined. Namely our main research fields BMs, BMI, and lean startup as well as their connections regarding the research purpose. Also, we show how digital technologies influence these areas. In chapter 3 we describe the methodology and research design. We will provide an overview of our sampling, data collection, analysis process, and illustrate how our empirical research met quality criteria and ethical principles. In chapter 4 we present our empirical findings, by outlining enablers and barriers for established companies when using lean startup as a tool for digital BMI. Our findings are then analyzed in chapter 5. Highlighting main factors hampering and facilitating lean startup in established companies and discuss those in the context of existing theory to answer our research question and to propose our framework. Finally, we will conclude our study in chapter 6 by showing findings, highlighting enablers and barriers when working with lean startup in digital BMI, giving theoretical and practical implications, discussing limitations to our work, and proposing further research.

2. Literature Review

___________________________________________________________________________

This section examines the current state of literature regarding the phenomena under study. The literature collection process is described along with a literature review of relevant topics, including business models, business model innovation, and lean startup.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This study links different fields of research, specifically BM, digital BMI, and lean startup approaches. The research question emerged from combining these research areas. To gather relevant scientific articles and findings within these fields and to answer the research question appropriately, different scientific databases, such as Web of Science and Primo, were used. Further, to assure that only relevant and contemporary literature is used, we filtered our search for the newest publications as well as most cited publications. Specifically, relevant academic articles, used for this research, were collected by combining different search terms, like “Business Model Transformation”, “Business Model Innovation”, “Digital Business Model Innovation”, “Business Experimentation, “Lean Startup Approach” and “Established Companies”. We also used relevant articles to identify further appropriate academic sources for our study to assure high quality of research. More specifically, to get a deeper understanding of specific theories and themes, we used backward citation searching. The purpose of the literature review is to give an overview of relevant theories, definitions, and findings of our research frame. Moreover, it serves as a fundamental grounding for the empirical part of our study.

2.1 Business Model Innovation

In this chapter, we are outlining the terminology of BMs and digital shift of BMs to address the topic of BMI and further introduce the term digital BMI.

2.1.1 Business Models

The topic of BMs has gained much popularity in the research area of strategic business and business innovation. Before the introduction of the BM concept, scholars used organizational design or business strategy to describe aims and purpose of a company (Keen & Qureshi, 2006). However, nowadays there is a need to distinguish between business strategy and BM, as business strategy rather defines how a company is making business. Opposing to that, BM answers the question of what a company is doing (Keen & Qureshi, 2006). Still, these two concepts are closely linked as strategic analysis of companies is an inevitable element for BM design (Keen & Qureshi, 2006; Teece, 2010). Every firm is grounded in a BM, even if the company itself does not express it directly (Chesbrough, 2007; Foss & Saebi, 2018; Teece,

Charline Langner 2010). Many academics contributed to defining the term BM, however, there is still no mutually used definition (Foss & Saebi, 2018). Nevertheless, most scholars have agreed that BMs function to create, deliver, and capture value (Chesbrough, 2007; Foss & Saebi, 2018; Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Teece, 2010).

BMs are seen as a way to create value for customers and how the business turns market opportunities into profit through different actors, activities, and collaborations (Rajala & Westerlund, 2005; Zott & Amit, 2007). Afuah (2004) describes BMs as a set of activities a company performs, how it performs those and when it performs them. They represent all elements of a company’s business activities, their relationship, and interaction (Rachinger et al., 2019). Correspondingly, BMs define the building blocks of value chain, creating value by defining a set of activities from raw materials through to final consumers. BMs also outline structures of revenues, costs, and profits of a company when delivering value (Teece, 2010). Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) created a tool, named Business Model Canvas, which visually illustrates nine building blocks of any BM. Namely user segment, value proposition, channels, user relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partners, and cost structure. Because of the more customer-driven world, companies are obliged to rethink their business strategy and to complement revenues with a suitable BM to respond to the two main dimensions of BMs, specifically value creation and value capturing (Amit & Zott, 2012b; Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013). Value creation describes the identification of customers and their engagement with a company, whereas value capturing marks how novel value is delivered to customers and how money is made with it (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013).

2.1.2 The digital shift – Business Models and Digital Technologies

Digital technologies are directly linked to the development and transformation of BMs as they change how firms produce and deliver value (Keen & Qureshi, 2006; Vaska et al., 2020). They create value in a new way for businesses, optimize customer experience, and build new capabilities which support overall business activities (Dörner & Edelman, 2015). Thus, they make it necessary for companies to undertake a digital shift. In our study, we define digital shift as the transformation of a company’s existing BM towards a digital BM by adopting digital technologies. By doing so, digital technologies influence business activities by advancing BMs or even making former successful BMs now obsolete (Kiel et al., 2017; Tongur & Engwall, 2014). Baden-Fuller and Haefliger (2013) reflect on the correlation of digital technologies and

BMs, indicating to which extent and when digital technologies require changes in BMs to gain a competitive advantage. The authors claim that digital technologies and BMs interact constantly in a two-sided way (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013). Hence, the choice of a specific BM can determine how digital technology can be made profitable, but also digital technologies can influence the possibilities of BMs. Consequently, focus on customer engagement as well as value creation is increasing. To capture this novel creation of value, digital technology needs to be intertwined with the right BM (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013; Teece, 2010).

Integrating digital technologies into BMs reshapes and improves customer value propositions and leads to greater customer interaction and collaboration (Berman, 2012). Thus, it brings opportunities across the entire organization. As a result, digital technologies increase the speed of change and lead to transformations across industries (Bharadwaj et al., 2013). Implementation of digital technologies is completely reshaping traditional business strategies as business practices can now be carried out across boundaries of time, distance, and function (Banker et al., 2006; Ettlie & Pavlou, 2006; Kohli & Grover, 2008; Rai et al., 2012; Sambamurthy et al., 2003; Straub & Watson, 2001; Subramaniam & Venkatraman, 2001; Tanriverdi & Venkatraman, 2005; Wheeler, 2002). In this context, digital technologies are seen as an influence on three dimensions: (1) externally, meaning to digitally enhance customer experience, (2) internally, meaning to influence business operations, decision-making, and internal structures and (3) holistically, stating that all business segments are being affected, which leads to completely new BMs (Hess et al., 2016, 2020; Kaufman & Horton, 2015; Schuchmann & Seufert, 2015). Hence, digital technologies can change individual business elements within a BM, the complete BM, adding on different components of value chains, or the recombination of networks of different actors within a BM (Schallmo & Williams, 2018). To what extent a BM will be changed depends on the degree of implemented digital technologies.

It is argued that digital technologies bring new opportunities for the conceptualization of BMs as well as novel forms for organizations to create and capture value (Vaska et al., 2020). Opposing to that, drastic changes resulting from the emergence of novel digital technologies (e.g. mobile technologies, cloud computing, big data, etc.) make it extremely hard for established companies to stay ahead of competitors that are born-digital and familiar in handling novel digital technologies. According to Piccini et al. (2015), traditional structures of whole

Charline Langner industries are being transformed with the introduction of novel digital technologies, which contains many challenges concerning BMI. However, the new digital environment forces all companies to adapt to these changes brought by digital technologies to stay competitive (Subramanian et al., 2011). Especially for established companies, this can be a challenging task. 2.1.3 Digital Business Model Innovation

BMs are capturing how value is created and delivered (Chesbrough, 2007; Foss & Saebi, 2018; Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Teece, 2010) and digital technologies in this context are a great source of innovation and an enabler for advancing and developing BMs (Rachinger et al., 2019). However, the highly competitive and rapidly changing business environment today implicates that BMs became a significant factor for competitive advantage (Berends et al., 2016) and are also an important source of innovation (Rachinger et al., 2019). Therefore, it is beneficial for companies to change their process of value creation and capturing (Berends et al., 2016) and to develop appropriate capabilities to innovate their BMs (Chesbrough, 2010). Berends et al. (2016) describe BMI as a “multi-step, multi-mechanism learning process” (p. 200), meaning that it is rather a loose trail-and-error-process of making changes and adjustments, and learning from these to develop new BMs. However, BMI does not only result in completely novel BMs and can also be the outcome of innovating existing ones (Rachinger et al., 2019).

Often, novelty and efficiency are key aspects named in BMI (Amit & Zott, 2012b). However, in large enterprises, this expectation can conflict with traditional setup and structures as managers see existing business threaten and are therefore less willing to experiment (Chesbrough, 2010). There is a conflict between existing and new business (Berends et al., 2016; Christensen, 2003) that makes BMI challenging for established companies, also referred to as ambidexterity of exploitation and exploration (O'Reilly & Tushman, 2004). The term ambidextrous organization describes companies that maintain and protect their established business while giving space for new, disruptive innovation beyond their existing products and services (O'Reilly & Tushman, 2004). In this context, existing structures can both facilitate or hamper BMI, as resources might be useful for innovation processes, but existing structures could also lead to inertia as opportunities might not be perceived as such (Berends et al., 2016). Thus, it is challenging to balance between exploiting existing businesses while exploring potentials for innovation growth (O'Reilly & Tushman, 2004). Hence, established companies need to identify what made them successful in the past and predict what can work in the future,

to make appropriate changes regarding their BM. The difficulty is to understand the complexity of BMs and to make right assumptions about different elements of a BM and their interactions (Berends et al., 2016). Also, it is hard to predict whether or not a BM will be successful (Berends et al., 2016). Generally, it is key to identify and understand barriers of BMI within the organizational context and to make necessary changes in leadership, culture, and organizational structures accordingly (Berends et al., 2016; Chesbrough, 2010). Therefore, it is important for established companies to learn through experimentation (Chesbrough, 2010) and to build an effective learning process to be innovative and to create novel BMs (Berends et al., 2016). Also, it is necessary to understand, that experiments can and will fail and that it requires an open culture allowing such failures to learn from them (Berends et al., 2016; Chesbrough, 2010). According to Chesbrough (2010), it requires internal leaders to drive experimental change in BMI to create new and better value propositions. Coming back to the phenomenon of ambidexterity, it is crucial to drive cultural change while maintaining existing businesses and to find a solution how both can coexist and later be combined within a company (Chesbrough, 2010).

As we argue that established companies need to undertake a digital shift of existing BMs by adopting digital technologies, we define digitization of BMs as digital BMI. In this context, the influential character of digital technologies on BM has three different dimensions: (1) Digital technologies can lead to optimization of existing BMs, meaning cost efficiency by using digital technologies for instance. In this context, optimization refers to digitization of products and services. (2) Digital technologies can transform current BMs, meaning an extension of existing BMs or changing individual elements by adopting digital technologies. Thus, they digitize processes and decision-making. And (3) digital technologies can empower the development of novel BMs, that either replaces or accomplishes existing ones by completely changing value propositions (Berman, 2012; Matzler et al., 2016; Rachinger et al., 2019). Therefore, we define the three dimensions of digital BMI as (1) optimization, (2) transformation, and (3) novel BM creation, meaning that established companies are to some extent adapting and implementing digital technologies in their BMs.

2.2 Lean Startup as a Tool for Digital Business Model Innovation

In the field of digital entrepreneurship, lean startup has already been used as a tool to validate and innovate BMs (Ghezzi, 2020) and is a scientific approach for a fast go-to-market strategy

Charline Langner (Tohanean & Weiss, 2019). In the following, we introduce lean startup as an agile method for digital BMI and further bring it into the context of established companies.

2.2.1 Business Experimentation and Lean Startup

Lean startup can be used to advance innovation processes by bringing lean thinking into organizations (Balocco et al., 2019) and to continuously reinvent BMs. Such a task requires experimentation and customer involvement (Xu & Koivumäki, 2019), which are essential aspects covered in lean startup. Business experimentation is a new, emerging field in BMI, and it is argued that experimental learning significantly influences innovation processes (Berends et al., 2016; Weissbrod & Bocken, 2017). Meaning, that organizations that constantly experiment with innovative ideas and concepts are more likely to be successful with the intent (Chang et al., 2012). Build-measure-learn cycles (Ries, 2011) enable every size of company to think and operate like a startup and convert ideas into feasible products and services. By using this approach, it is less about following a clear plan and rather doing a trial-and-error experiment (Xu & Koivumäki, 2019). Research revealed that business experimentation not only enables learning and innovation but also reduces uncertainty, can help to interact and communicate with customers and other stakeholders, and also helps to overcome organizational inertia (Bocken & Snihur, 2020). Thus, BMI needs to be seen as an ongoing process that requires appropriate mechanisms (Tohanean & Weiss, 2019).

2.2.2 Lean Startup

In 1997, the term lean philosophy was introduced by Womack & Jones (1997) initiated with novel development to put high emphasis on customers’ interest. Novel customer value at that time changed production systems and business activities in the entire construction industry. Inspired by the Toyota Production System, where it is all about reducing waste in industrial processes, the authors introduce „five principles of lean”, namely (1) create value for customers, (2) identify value streams, (3) create flow, (4) produce only what is pulled by customers, and (5) pursue perfection by continuously identifying and eliminating waste (Womack & Jones, 1997). Those principles demonstrate a high focus on customer value that is implied by the lean philosophy (Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2020). It also shows a customer or user-centric approach.

Ries (2011) and Blank (2013) firstly transferred lean philosophy from the manufacturing industry to the entrepreneurial world. The idea of lean startup evolved when Eric Ries was confronted with the failure of his products getting traction (Leoveanu, 2018). As an engineer,

he figured that the problem had to do with technical problems of the products. However, it turned out that he just spent a lot of time building things nobody was interested in (Ries, 2011). With this experience, he was not alone, as 75% of startups failed in the initial startup phase due to traditional approaches (Blank, 2013). The commonly known manner to create a BM was to build a business plan with a five-year prospect, which was pitched to investors. If the pitch was successful, the business plan would be realized and brought to market. Only then would entrepreneurs get feedback from customers about products or services. This means, entrepreneurs would find out if the initial business idea was a hit or miss, only after a product was already available on the market when lots of time and money was already spent (Blank, 2013). So, there was a need to change this process, making the creation of novel BMs less risky.

As a solution, different lean startup approaches have been introduced (Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2020), such as lean startup (Ries, 2011) and customer development methods (Blank, 2013). Ries (2011) and Blank (2013) define lean startup approaches as a startups’ way of identifying all preferred features of a business idea, activities, and processes of customers and which are non-relevant, or even not wanted. To reduce uncertainty about a business’s viability, startups need to iterate their business ideas as quickly as possible applying the method of learning-by-doing (Gans et al., 2019; Ott et al., 2017). Getting the right business idea quickly to market has a positive impact on its success in the long run (McDonald & Gao, 2019; Zott & Amit, 2007). Therefore, lean startup is a useful tool helping to iterate business ideas quickly, up to the point where entrepreneurs are able to formulate a sound BM and make early assumptions about its feasibility (Blank, 2013; Ries, 2011). The method contains two main features. Firstly, formulation of hypotheses in nine areas of a business idea (called Business Model Canvas) and secondly, the approach of getting-out-of-the-building, meaning that each hypothesis will be tested by interviewing customers and other stakeholders (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Ries, 2011). The Business Model Canvas is used to visually illustrate the complete extent of a business, its goods, services, parties involved, and how ownership of goods/services will be exchanged. Each of the nine building blocks withholds assumptions about the business idea and is being used as hypotheses to test BMs (Leatherbee & Katila, 2020). The goal is to test all hypotheses with potential customers to build a strong BM with (dis)confirmed hypotheses (Leatherbee & Katila, 2020). The canvas supports lean startup as it causes entrepreneurs to ask the right questions, such as: Who are the customers?, What are you building for them?, What is the value proposition?, What are the right channels to reach your customers?, How do you

Charline Langner keep existing customers and how do you get new ones?, What are your pricing tactics?, What is your revenue model?, What resources do you need and which partners do you need? (Blank & Euchner, 2018). Traditionally when building a BM with the canvas, building blocks were filled in as facts, without testing them. With lean startup, the fields are being filled with hypotheses that are being tested out-of-the-building with potential customers (Blank & Euchner, 2018). The method makes initiation of a new BM less risky, as it uses experimentation instead of planning, valuable customer feedback instead of making assumptions, and intuition and an iterative design process instead of traditional time-consuming and costly perfectionistic design upfront (Blank, 2013). Lean startup, therefore, reduces uncertainty about a business idea’s viability and helps to indicate if there is an actual customer need as well as to quickly decide whether to stick with a BM (persevere), to change/adapt it (pivot), or not proceed with the idea (perish) (figure 1).

Figure 1: Lean startup hypothesis process (Eisenmann et al., 2012).

Lean startup makes use of a hypothesis-driven attempt, in which innovators and entrepreneurs formulate their business intent into measurable hypotheses. These hypotheses are incorporated into a lean startup Business Model Canvas and can furtherly be combined with formulation of user stories as well as use cases and first estimate business cases. In a following step, these hypotheses are being tested with potential customers. If an entrepreneur decides to persevere with a BM, it will then be translated into a minimum viable product (MVP). Eisenmann et al. (2012) define a MVP as the smallest set of activities needed to disprove a hypothesis. Ries

(2011) describes it as a product that combines just a few features which makes it possible for early adopters to give useful feedback for further product development. Early adopters are involved in hypotheses testing through experiments with a MVP, where they give feedback while using it. This process is highly valuable for the development, as a product is based on customer needs, opposed to the approach of basing evaluations on secondary data or desk research or even pure assumptions (Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2020). Based on experiments’ results with early adopters and lead users, hypotheses can be proven right or wrong. Continuous testing and improving are referred to as build-measure-learn loops (Ries, 2011). In these loops (figure 2) a MVP is built (Build), then customer feedback is given and evaluated (Measure) and from those insights, learnings are being generated (Learn).

Figure 2: Build-Measure-Learn loop (Ries, 2011).

MVPs, as well as BMs, will be adapted according to customers’ preferences (Ries, 2011). Thus, a MVP is used to validate or invalidate assumptions (Blank & Euchner, 2018). This process is repeated until all hypotheses are validated through MVP testing. According to Eisenmann et al. (2012), at that point, a product or service achieves its approved product-market-fit. In addition, this process helps not only to validate hypotheses but also to improve products as such. Nobel (2011) additionally highlights the emphasis on speeding up the process, as with lean startup companies do not need to spend several months perfecting a full-featured product but rather launch a quickly developed MVP. Therefore, build-measure-learn cycles shall be executed quickly to fail early and to succeed sooner (Brown & Katz, 2019; Ries, 2011). In turn, MVPs help companies to quickly market products that are highly relevant for their customers and have a proven product-market fit.

Charline Langner Many startups have succeeded with lean startup (Leatherbee & Katila, 2020), such as Dropbox and Zappos, however, it still has some limitations. Ladd (2016) argues that despite its well-deserved popularity, the method requires strict tailoring and needs to be used with care. It is crucial to generate unique and testable hypotheses, which can be challenging as lean startup does not per se guides through the process (Bocken & Snihur, 2020). Literature states that continuous testing of multiple hypotheses decelerates the process and leads to disheartened and impatient founders (Ladd, 2016). Moreover, it is argued that the customer-centric approach presents some pitfalls, as it is difficult to capture non-biased and valuable customer feedback to confirm hypotheses (Felin et al., 2019; Ng, 2014; Nirwan & Dhewanto, 2015). Also, heavy reliance on customer feedback is harshly criticized, as customers might not necessarily have better knowledge of a business idea or product (Felin et al., 2019). The customer-centric approach also leads to focus on what customers want today and fails to predict what will occur in the future (Mollick, 2019). Additionally, novel business ideas are always harder to understand for customers and tend to be initially disliked by them (Christensen et al., 2013). It is even argued that regulatory and administrative barriers hinder the process of obtaining customer feedback and as a result slow down the whole BMI process (Nirwan & Dhewanto, 2015). Therefore, it is questionable if lean startup helps to generate radical BMs and hence, is rather a tool for incremental change (Felin et al., 2019; Mollick, 2019). Another critical aspect is handling MVPs, as established companies often hesitate to create a perceived inferior product, that might fail to satisfy existing customers’ needs (Nirwan & Dhewanto, 2015). Opposingly, according to Zuzul and Tripsas (2020) entrepreneurs that strongly rely on their original business idea might be less successful than entrepreneurs that continuously update their BM, which is a favorable aspect supporting lean startup. Also, it is argued that a BM idea can be both radical and incremental when applying lean startup, as it is not a tool to generate novel business ideas but rather to test if an idea is solid (Bocken & Snihur, 2020). Despite the skepticism (Felin et al., 2019; Ladd, 2016; Nirwan & Dhewanto, 2015), lean startup has been adopted around the world as a popular solution to avoid business failure (Nirwan & Dhewanto, 2015) and is a successful tool for BMI (Leatherbee & Katila, 2020). Opposing to its popularity in the business context, lean startup has not been thoroughly investigated in empirical research (Leatherbee & Katila, 2020). Hence, it is necessary to fill this research gap and to examine how established companies can successfully use lean startup as a tool for digital BMI.

2.2.3 Digital Business Model Innovation with Lean Startup in Established Companies

As startups offer new products and BMs at a high speed, they put traditional actors and especially established companies under high pressure (Edison et al., 2018). Startups are constantly in close collaboration with potential customers, indicating gaps in existing market offers to find new, scalable BMs. This means, for established companies in order to compete with these disruptive players, they need to find new ways of creating and capturing value (Rejeb et al., 2008). Therefore, a high focus for established companies is put to innovate and act like startups to regain leading positions as well as to compete with startups. They realize that startups are no longer ankle-biters, but serious competitors that can take over their business or even to disrupt entire markets and that there is a need to rethink their BMs (Blank & Euchner, 2018). Thus, established companies start adapting startup techniques to compete with startups, but oftentimes fail to implement tools as an end-to-end solution for growth. Rather they use it for experimentation but are not capable to bring new BMs to scale and market (Blank & Euchner, 2018). Especially for established companies, digital BMI can be a huge challenge as they might not be used to the fast-paced digital environment. Therefore, business experimentation is needed to react faster to new market conditions by continuously creating and testing hypotheses about novel or changed BMs (Bocken & Snihur, 2020).

Especially, because established companies rely on and aim to fulfill existing customer needs while simultaneously gaining new customers, the customer-centric approach of lean startup can help them to do both. In this way, they centralize all their efforts to their main and necessary business operations, focusing on what customers want and need (Ries, 2011). Through low-cost experimentations with MVPs, new ideas can be tested easily and fast with customers, and thus implement a startup mentality in large enterprises (Bocken & Snihur, 2020) without making huge investments or long-time planning (Mansoori, 2017; Ries, 2011). Moreover, continuity is a major advantage of lean startup as a tool for BMI. As pointed out before, it is important for any company to continuously rethink its BM to stay competitive. With feedback loops, as an essential part of lean startup, established companies can constantly challenge and reinvent their business. In this context, it is important to truly understand customer needs and work closely together with them to generate learnings from customers rather than selling them something (Mansoori, 2017; Xu & Koivumäki, 2019). Ghezzi (2020) outlines the importance of simple heuristics instead of abstract guidelines to successfully apply lean startup and make use of existing resources. Further, lean startup requires agility on every level in terms of culture

Charline Langner and organizational structure (Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2020) as BMI or change in general, especially grounded in digital technologies, forces companies to adapt in the way they think and act. Such agile structures can be found in (digital) startups (Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2020) and thus needs further investigation in established companies that are facing a digital shift. Xu and Koivumäki (2019) explain challenges of lean startup with an enormous change from existing procedures to agile methods. Before, companies predicted what customers want. Now, by including them in the process it shifts to customers telling companies what they want, thus altering the competitive landscape and forcing companies to be primarily fast and agile. Therefore, organizational structures and operational processes need to allow the inclusion of customers as external sources (Mansoori, 2017). However, once an innovative idea is generated, the lean startup process can yield novel and innovative BMs (Bocken & Snihur, 2020) and the lean perspective can help to shift learnings from a small task to an organization-wide implementation in a step-by-step process (Balocco et al., 2019).

According to Ries (2011), the core idea and activities of lean startup offer many benefits for established companies, which is why lean startup has gained interest from companies, such as General Electrics, 3M and W.L. Gore, etc. (Edison et al., 2018). According to a study by the Harvard Business Review on 170 corporate executives, 82% of them are using elements of lean startup in their business context (Kirsner, 2016). Still, many large companies struggle with lean startup. One critical aspect is that they fail to connect innovation teams with operational groups (Blank & Euchner, 2018). Another problematic factor is that oftentimes established companies have managers with a rather traditional leading styles that fail to understand the needs to apply lean startup thinking within a company (Blank & Euchner, 2018). Also, employees of large organizations are motivated for different reasons as startup employees, who are rather motivated by passion and drive to make a difference (Blank & Euchner, 2018). Nevertheless, lean startup is nowadays one of the most common and trusted innovation methods not only by startups and entrepreneurs but also for corporations and policymakers (Leatherbee & Katila, 2020).

However, scientific and empirical insights about using lean startup in established companies are still rare. Hence, there is an urgent need to understand how to successfully use lean startup in those companies (Edison et al., 2018). Thus, we aim to identify enablers and barriers influencing usage of lean startup as a tool for digital BMI in established companies.

3. Methodology

___________________________________________________________________________

This chapter provides an overview of our research environment outlining the research’s underlying philosophy, our research approach, and design, as well as data analysis including quality insurance and ethical considerations.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

3.1 Research Philosophy

Research philosophy consists of the ontological and epistemological view of a study. Ontology describes basic assumptions researchers hold about the nature of reality and existence, basically how we see the world (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). For this study, we ground our assumptions on relativism. Relativism defines reality as a subjective product of how individuals see the world, as reality depends on individual perspectives, and truth is created subjectively by individuals (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). This perspective suits our study best as we generate our data from interviews with diverse experts, with different knowledge, experience, and expertise in lean startup for digital BMI and each one perceives reality differently. Furthermore, we generate our knowledge through our observations and gathered data from interviews and hence, build a multi-sided truth of the investigated topic. In relativism, scientific laws are not predefined but created by people (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Hence, we explore heterogeneity of opinions on our research themes digital BMI and lean startup, as we also include different standpoints and perspectives, due to the different roles of the respondents. Epistemology describes how knowledge is generated in terms of how researchers enquire the physical and social world, or simply how we know what we know and how we investigate the world (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Based on our relativistic ontological viewpoint, our study’s underlying epistemology is social constructionism. Social constructionism aligns with the perspective that reality and knowledge are created by people and it is important to acknowledge individual perspectives (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). We base our findings and emerging knowledge on our interviewees’ experience and therefore, need to see reality in different ways even though we aim to develop a common understanding by identifying certain patterns and similarities. From a social constructionism position, we as researchers are reflective observers. Thus, we take active part in the research by interacting with interview partners, interpreting our findings, developing deeper understanding of the topic, as well as explaining and generalizing the research phenomenon and its outcome. By doing so, we gather rich data about lean startup as a tool for digital BMI in established companies and construct an understanding of the

Charline Langner research fields lean startup and digital BMI to later generalize our knowledge through theoretical implications.

3.2 Research Approach

Based on our research philosophy we conducted an exploratory, qualitative research. Coherently with our ontology and epistemology, we choose grounded theory as the underlying methodology, following an abductive approach. Thus, we aim to collect and analyze data by identifying common patterns to extend existing theory and eventually generating new ones (Saunders et al., 2012). In comparison to deductive or inductive research, the abductive approach allows us to explain, develop, and change the theoretical framework at any time in the research process (Saunders et al., 2012). It is a mixed approach of inductive and deductive that aims to derive novel insights from gathered data to contribute to existing theory and thus emphasizes researchers to acquire a deep understanding of the topic beforehand (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). As we investigate lean startup as a tool for digital BMI, we intend to contribute to and extend current theory about lean startup and BMI. Thus, we combine fields of lean startup and BMI, extending BMI in the digital context and investigate both in a new context within established companies.

Therefore, we choose grounded theory by Charmaz (2000) as it aligns best with our relativism and social constructionism viewpoint, as well as the abductive approach. As we aim to identify enablers and barriers of using lean startup for digital BMI in established companies, we consider different perspectives of our interviewees due to different roles within or without company boundaries, years of experience, and expertise of each respondent. We used literature to get familiar with lean startup and digital BMI to design our theoretical framework by combining these fields and putting them in the context of established companies. However, we did not use any pre-assumptions regarding our research purpose when conducting the research and analyzing the data. In general, grounded theory examines a research problem without making prior assumptions where theory emerges from data by continuously comparing it with each other to identify common patterns (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). However, Charmaz’s (2000) approach allows and recommends prior familiarization with literature to get a pre-understanding of the topic and thus to better examine data later in the research process. Compared to other approaches of grounded theory, the main difference in Charmaz’s (2000) approach is that results should emerge from the interaction between research subject and researcher. Therefore, we understand our role as reflective observers and co-creators of

meaning by interacting with our interview partners. Rahmani and Leifels (2018) show how an abductive approach can be used with grounded theory arguing that even though the literature review is influencing the research question, there is no need to direct data collection and analysis towards any pre-defined theories. Similar to our study, we developed our research question based on the identified gap in literature but not used existing concepts to analyze our data, rather we aimed for “surprising facts” emerging from data (Saunders et al., 2012).

3.3 Research Design

3.3.1 Data Collection

The collected qualitative data consist of primary data, which is conducted through semi-structured interviews with diverse experts of lean startup usage for digital BMI. Aligning with

our study’s purpose, to understand enablers and barriers of lean startup for established companies, we collected data from ten in-depth, semi-structured interviews. The interviewees are all experts in lean startup as a tool for digital BMI in established companies, as they all have been or are working in/with established companies using lean startup. A detailed description of our experts, their roles, and experience with lean startup as a tool for digital BMI in established companies, is shown in table 1.

We used in-depth, semi-structured interviews, as we want to explore deeper meanings, patterns, and relations of different fields concerning the usage of lean startup for digital BMI in established companies. As most of the experts work in different industries with different roles and perspectives (table 1), we thrive to cover as many aspects as possible for using lean startup in different established companies. Therefore, semi-structured interviews appear as the most appropriate method. Moreover, we wanted to be flexible with questions throughout the interviews, to make sure to react and cover areas that we initially did not think about. Thus, semi-structured interviews allow to make answers comparable but still give space to spontaneously react to responses and to ask follow-up questions (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). We did not conduct completely structured interviews, as they tempt us to make assumptions before having the interviews as well as to leave out important insights, which we do not cover with our planned interview questions. Also, as we aim to explore which enablers and barriers established companies face when working with lean startup, we refrain from working with

unstructured interviews. Without giving any guidelines and setting a frame, we would not collect useful and appropriate data on our intended research, which is why we choose to have a semi-structure (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Charline Langner

Table 1: Overview of Interview Partners.

Interviewee Job Description Industry External/ Internal Perspective

Date Length Background & Experience with Lean Startup

Respondent 1 Project & Innovation Manager & Product Owner New Business Logistics Internal perspective

30.03.21 58 min Uses Lean Startup method for the last six months for an internal intend to create novel digital business models within the boundaries of an established company.

Respondent 2 Management Consultant, Agile Coach & SAFe 5.0 SPC

Consulting External perspective

01.04.21 65 min Works as an external coach for established companies that are using the lean startup method for digital business model innovation.

Respondent 3 PhD. Advisor and Lecturer on Business Model Innovation and Customer Value Creation Consulting/ Education External perspective

02.04.21 70 min Acts as an external coach for business model innovation for 13 years. Teaches business model innovation with lean startup for the last six years.

Respondent 4 Agile Coach and Digital Consultant for digital Transformation and New Work

Consulting External perspective

06.04.21 62 min Acts as a digital coach for the last nine years, mainly for established companies that are in the process of digital transformation. Has had one big project for two years where he consulted an established firm in the process of digital transformation with the help of the lean startup method.

Respondent 5 Innovation Lead Production (B2B)

Internal perspective

06.04.21 66 min Acts as lean startup ambassador for three years. Was commissioned by management of an established firm to work as an innovation lead with lean startup in order to create novel digital business models and to digitally transform the traditional and existing business models of the established company for the last two years. Respondent 6 Innovation

Manager

Consulting External perspective

08.04.21 63 min Acted as an external coach for one year for established companies that practice (digital) business model innovation and used lean startup method in this context.

Respondent 7 Innovation and Technology Consultant

Consulting External perspective

08.04.21 58 min Works as an external consultant for different traditional companies that are in the process of digital transformation and supports them with digital business model innovation with lean startup method. Respondent 8 PhD. Organizational Development Consultant Corporate Incubation Automotive Industry (Innovation Lab) Internal perspective (Corporate incubation)

16.04.21 61 min Set up and worked for almost four years as a business accelerator for the corporate organizational development in form of an innovation lab of a big corporate automotive group. There, different initiatives for digital business model innovation were practiced with the lean startup method.

Respondent 9 Organizational Development Consultant Corporate Incubation Automotive Industry (Innovation Lab) Internal perspective (Corporate incubation)

21.04.21 56 min Colleague of Respondent 8. Worked for three years at the innovation lab of a big corporate automotive group. Different initiatives for digital business model innovation were practiced with the lean startup method.

Respondent 10 Founder of Innovation Hub; Agile Coach Innovation Innovation Hub External perspective

23.04.21 59 min Background in a digital factory incubation lab of a big automotive group. Founder of an innovation hub where organizations are supported to master innovation in a digital world since one and a half years. Works with different agile methods, inter alia Lean Startup, to develop digital business models, products and services for and with established medium-sized enterprises.

3.3.2 Sampling Strategy

As a sampling method, we used non-probability sampling with purposive sampling, as we aim to identify reasonable specimens of the researched phenomenon (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). As our research purpose is to understand enablers and barriers of lean startup for established companies, we need experts that are familiar with the research topic, that have broad experience and knowledge within this field. Meaning, that only a small collection of individuals has the required expertise, in working with lean startup as a tool for digital BMI, which we can choose from. With probability sampling methods the data sample could be biased, as not everybody has expertise and experience working with lean startup for digital BMI in established companies.

To get in contact with potential interviewees, we first did online research on professionals working with lean startup for digital BMI in established companies. Therefore, we searched for the keywords “Lean Startup” and “Business Model Innovation with Lean Startup” on Google and LinkedIn. From there we identified several persons that appear to be experts in using lean startup for digital BMI. To detect if a person was specifically suitable for our study, prior we set different criteria for selecting our interviewees. First, the person needed to have knowledge and a deep understanding of lean startup. To ensure this criterion, we checked their working experience with lean startup, and we only contacted individuals if they directly stated that they are/have been working with lean startup. All our experts explicitly mentioned in their online communication, either on their LinkedIn profile or on the respective company website, that they have been/are working with lean startup. Some experts are moreover acting as lean startup ambassadors or are teaching lean startup. This is how we made certain that they have deep understanding and knowledge within the field of interest. Another criterion which we set, was that the experts understand lean startup as a tool for BMI, and not only as an agile working method as such. To ensure this criterion, we asked the experts how they work with lean startup. We only set an interview, if the individuals stated that they use it as a tool for BMI. Furthermore, we made sure that the experts use lean startup for BMI in companies that are facing a digital shift, meaning that the experts have experience with using lean startup for digital BMI. This leads to another criterion that we set priory. As lean startup is commonly known as a method for startups, we needed to make sure that the experts work with established companies and not for/with growing companies and startups. To ensure this we asked the experts directly for/with which types of company(ies) they use lean startup. Again, we only scheduled interviews with

Charline Langner experts that explicitly mentioned that they use lean startup in/with established companies. Also, it was interesting for us, to understand if a person acts as an external coach or consultant, uses lean startup within company boundaries, or in-between both positions, e.g. in a corporate incubation position. This way, we made certain that we cover different perspectives of using lean startup to get a holistic understanding. Only if a person corresponded to all above-named criteria and was indicated to be suitable for our research intend, we scheduled an appointment for an expert interview.

To avoid sampling bias, we aim to make data collection as representative, yet still comparable, as possible (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). For this, we chose diverse interviewees, that all work with lean startup for digital BMI in established companies, but in different positions and perspectives (table 1). Meaning, that we interviewed experts that function as external consultants as well as employees working with lean startup as a tool for digital BMI and people that function as innovation leaders, supervising usage of lean startup for digital BMI. Also, some of the experts act as corporate incubators, for instance in corporate innovation labs, meaning they work independently in parallel to the core business of established companies to innovate existing BMs. Thus, we have different perspectives (internal and external) on using lean startup as a tool for digital BMI. This helps us to critically reflect on empirical findings. Additionally, all interviewees have different years of experience within the field. Moreover, all experts work in different markets, reaching from the automotive industry, finance, to production and manufacturing. Still, all respondents work for/with established companies in Germany that were founded before the dotcom bubble (1995-2000) and are now facing a digital shift of their existing BMs.

3.3.3 Interview Design

We conducted ten semi-structured interviews between 30th of March and 23rd of April 2021 using an interview guide (appendix 1) containing a set of pre-defined questions. The interviews lasted on average one hour and thus, we gathered more than ten hours of interview recordings (table 1). We did not specify an explicit number of interviews that we planned to conduct, as we aimed for knowledge saturation. This was achieved with the 9th interview and confirmed with the 10th, as no new data derived.

The interview guide was developed with different fields of our research purpose and key findings from the literature review. Also, the interview guideline was tested with one expert

before the planned interviews to detect unsuitable topics and to see if the interview guideline works in practice. This expert was a suitable choice to test the interview questions, as the expert has been recently using lean startup for digital BMI in an established company. There the expert started several projects, applying lean startup, to create novel, digital BMs. The company was founded in 1885, is very conservative, and is slowly proceeding in the digital transformation process, which makes it fit perfectly to our criteria. Also, the expert has theoretical knowledge from his academic background. From the feedback of the test respondent, we learned that some questions were still too narrow and needed to be rephrased to not bias the interview outcome. Also, it was a helpful trial on how to lead respondents through the interview guide.

The interview guide covers two main topics: First, general understanding of the topic and how the respective companies use lean startup and secondly, the experts’ experience with lean startup as a tool for digital BMI in established companies. During the interviews, we asked our experts four open questions about their experience with lean startup as a tool for digital BMI, two questions about positive aspects as well as three questions concerning which barriers and difficulties they experienced and how they dealt with them. Also, we asked six questions about advantages and drawbacks of lean startup as a tool for digital BMI in established companies. As we used a semi-structured interview guide, during the actual interviews we adapted some additional open questions (see optional questions in appendix 1), which came up spontaneously as a reaction to the respondents’ experiences. Accordingly, we added some questions concerning the experience with handling digital BMI in general and the potential for improvement.

All interviews were conducted digitally, using online video platforms, namely Zoom and Microsoft Teams, as those were our respondents’ preferred platforms. This approach was most suitable, as the respondents were all spread around different locations in Germany. All interviews were conducted in German, transcribed with the software trint.com, and then manually checked for errors. We choose to conduct interviews in German as our participants felt more comfortable with using their mother tongue and we expected to get a more detailed description of their thoughts and opinions about their experience of using lean startup for digital BMI in established companies.

Charline Langner

3.4 Data Analysis

Aligned with our methodology, we use the open approach of grounded analysis to analyze our gathered data. Grounded analysis is a holistic approach in qualitative research, often used in combination with grounded theory methodology, aiming to develop a theory based on given data (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). We see this technique as suitable for our study as it gives us the possibility to not only confirm existing theory on lean startup and digital BMI but also to discover new findings to get deeper understanding of the research phenomena. As we are using an abductive approach and aim to identify enablers and barriers of lean startup as a tool for digital BMI, grounded analysis offers us to explore novel insights about the research topic, beyond the usage in digital startups, in the context of established companies. Therefore, we intend to compare different perspectives of our research participants and their experience of using lean startup in established companies to derive new knowledge. Thus, we aim to contribute and extend existing literature about lean startup and digital BMI from using it in startups to the use in established companies. Through constant comparison of the data, following the seven steps of grounded analysis, we identified common patterns in form of codes and categories and built a holistic understanding and theory of the studied phenomenon. The seven steps are (1) Familiarization, (2) Reflection, (3) Open or initial coding, (4) Conceptualization, (5) Focused re-coding, (6) Linking, and (7) Re-evaluation (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Following these principles, we first familiarized ourselves with the data by listening again to interview recordings and going through interview transcripts. We already started with familiarization in the data collection process by writing notes during the interviews, listening to our recordings, and reading interview transcripts several times. We made initial comments and frequently discussed our impressions and thoughts after each interview. Whenever we identified interesting new topics related to lean startup as a tool for digital BMI, we adjusted our interview guide for the next interviews. These adjustments are illustrated in our interview guide (appendix 1) as optional questions emerging from the interviews. After conducting all interviews, we reflected on the data in the context of our study asking what enablers and barriers occur when using lean startup for digital BMI in established companies. Afterward, we went through our interview transcripts for initial coding once more, by summarizing the most important quotes from our interviewees in codes. For the first coding, we worked together taking the first data set (Respondent 1) to identify and discuss a first set of codes that seemed