J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITYL o c a l C e l e b r i t y E n d o r s e m e n t

- Can You Go Far by Staying Close?

Bachelor Thesis within Business Administration Author: SARA EKBERG 860303-1629

LINN MELLGÅRD 860120-7429 MAGDALENA MICKO 870323-7480 Tutor: HAMID JAFARI

Acknowledgements

The authors of this thesis would like to acknowledge the following people, who have been indispensable to us during the research process:

First of all, we would like to thank our awesome tutor Hamid Jafari who has guided and supported us in times of good and bad. Without him, this thesis would not have been possible.

We would like to thank Erik Hunter for taking time with us and providing us with inspiration. We would also like to thank Johan Larsson for guiding us through the SPSS jungle.

Finally, we would like to thank the students who participated in our survey and our fellow students for their moral support and constructive feedback.

Jönköping International Business School June, 2010

Bachelor Thesis within Business Administration

Title: Local Celebrity Endorsement- Can You Go Far by Staying Close? Authors: Sara Ekberg

Linn Mellgård Magdalena Micko

Tutor: Hamid Jafari

Date: Jönköping, June 2010

Keywords: Celebrity Endorsement, Local Celebrities, Well-known Cele-brities, Celebrity Capital, Reputational Capital, Marketing Communication, Communication Effectiveness

Abstract

Background: Celebrity endorsement consists of a written or spoken statement from a publicly known person, proclaiming the benefits of some product or service. Previous research on celebrity endorsement has proved it very successful in pro-moting brands or companies. Even though many marketing strategies exist, it can be especially effective for newly started ventures to apply celebrity endorsement in their approach. While celebrity endorsement may be a good way to over-come weaknesses, such as liability of newness and lack of le-gitimacy, new ventures often cannot afford to implement this strategy. Therefore, an option to this might be local cele-brity endorsement.

Purpose: This thesis investigates the impact of local and well-known celebrity endorsement on communication effectiveness. Method: The effects of using local celebrity endorsement has been

investigated by combining theories drawn from previous re-search with new insights gained from performing quantita-tive surveys on a sample of 240 participants.

Conclusion: Local celebrity endorsers are perceived more trustworthy and emotionally involved in the endorsement process than known celebrity endorsers. Local celebrities and well-known celebrities are perceived equally expert, attractive and capable of transferring meaning to the endorsed product. Local celebrity endorsement is overall more effective than well-known celebrity endorsement in communicating the endorsement message. It can therefore be a suitable tool for newly started ventures that cannot afford to employ more expensive, well-known celebrity endorsement in their quest for gaining quick reputational capital.

Table of Contents

1

Introducing Celebrity Endorsement ... 1

1.1 Background to Study: Celebrity Endorsement, A Good but Expensive Idea ... 1

1.2 Problem Discussion ... 2

1.3 Purpose: Investigating Communication Effectiveness of Local and Well-known Celebrity Endorsement ... 3

1.4 Research Questions ... 3 1.5 Delimitations ... 3 1.6 Definitions of Concepts ... 3 1.7 Thesis Outline ... 6

2

Theoretical Framework ... 7

2.1 Choice of Theory ... 72.1.1 The Importance of Reputational Capital ... 8

2.1.1.1 Reputational Capital for Newly Started Ventures ...8

2.1.1.1.1 Liability of Newness ...8

2.1.1.1.2 Lack of Legitimacy ...9

2.1.1.1.3 Lack of Financial Capital ...9

2.1.2 Celebrity Endorsement in Depth ... 10

2.1.2.1 Risks Associated with Celebrity Endorsement ... 11

2.1.2.1.1 Controversial Celebrity Endorsers ... 12

2.1.2.2 The Hefty Price Tag of Celebrity Endorsement ... 12

2.1.2.3 Celebrity versus Non-Celebrity Endorsers ... 13

2.2 Choosing the Right Celebrity ... 13

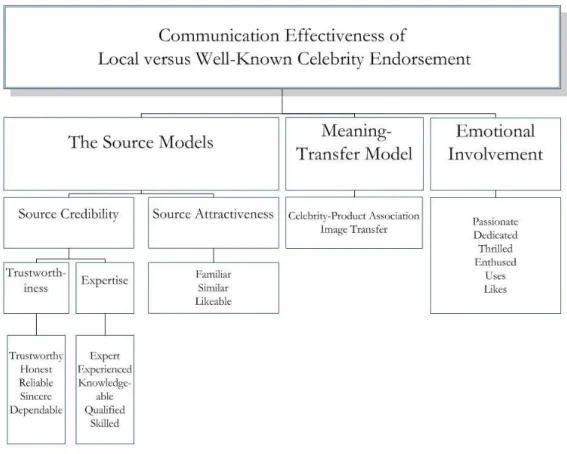

2.2.1 The Source Models ... 13

2.2.1.1 Source Credibility Model ... 14

2.2.1.1.1 Trustworthiness ... 14

2.2.1.1.2 Expertise ... 14

2.2.1.2 Source Attractiveness Model ... 14

2.2.2 Comments on the Source Models ... 14

2.2.3 The Meaning Transfer Model: Cultural Meaning and the Celebrity Endorser ... 15

2.2.4 Emotional Involvement ... 16

2.2.5 Summary of Models ... 17

3

The Local Endorser: Why it should Work... 18

3.1.1 Celebrities with Benefits ... 18

3.1.1.1 Trustworthiness ... 19

3.1.1.2 Expertise ... 19

3.1.1.3 Attractiveness ... 19

3.1.1.4 Emotional Involvement ... 20

3.1.1.5 Meaning Transfer ... 20

3.2 Communication Effectiveness of Local and Well-known Celebrity Endorsement ... 20

4

Methodology ... 22

4.1 Inductive or Deductive Approach ... 22

4.1.1 Chosen Method: Deductive Approach ... 22

4.2 Qualitative versus Quantitative Research Approach ... 23

4.2.1 Intensive and Extensive Data Collection ... 23

4.3 Research Strategy ... 23

4.3.1 Survey Design ... 24

4.3.1.1 Independent and Dependent Variables ... 24

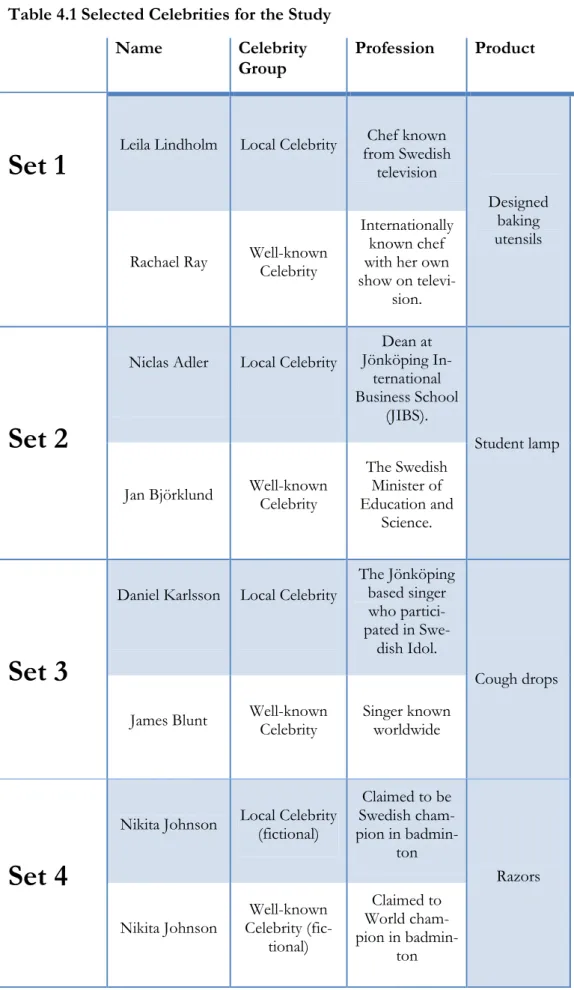

4.3.2 Choosing the Right Celebrity ... 24

4.3.2.1 Matching the Celebrities with Suitable Products ... 26

4.3.3 Designing Survey Questions ... 26

4.3.3.1 Chosen Survey Questions to Measure Communication Effectiveness ... 26

4.3.3.1.1 Pilot Study ... 28

4.3.3.2 Likert Scale, Also Called the Summative Scale ... 28

4.4 Survey Procedure ... 28

4.4.1 Background ... 28

4.4.2 Celebrity Advertisements ... 29

4.4.3 Participants ... 29

4.5 Validity and Reliability ... 29

4.5.1 Increasing Internal Validity ... 30

4.5.1.1 Reliability Tests ... 30

4.5.2 Increasing External Validity ... 30

4.5.2.1 Multiple Experiments... 30

5

Findings and Analysis ... 32

5.1 Data Analysis ... 32

5.2 Overview of Findings ... 33

5.2.1 Comparison of Mean Values ... 34

5.2.2 Hypothesis 1: Credibility ... 35

5.2.3 Hypothesis 2: Attractiveness ... 36

5.2.4 Hypothesis 3: Emotional Involvement... 37

5.2.5 Hypothesis 4: Meaning Transfer ... 38

5.2.6 Hypothesis 5: Communication Effectiveness ... 39

5.3 Analysis in Accordance with Theoretical Framework... 42

5.3.1 Credibility ... 42

5.3.2 Attractiveness ... 43

5.3.3 Emotional Involvement ... 43

5.3.4 Meaning Transfer ... 43

5.3.5 Communication Effectiveness ... 44

5.4 Analysis of Celebrity Endorsement Today ... 45

6

Conclusion ... 46

7

Limitations, Suggestions for Future Research and

Final Thoughts ... 47

7.1 Limitations ... 47

7.2 Suggestions for Future Research ... 47

7.3 Final Thoughts ... 48

References ... 49

Appendix 1: Source Credibility Scale (Ohanian, 1990) ... 54

Appendix 2: Survey Introduction and Questionnaire

(Swedish) ... 55

Appendix 3: Survey Introduction and Questionnaire

(English) ... 59

Appendix 4: Advertisement Leila Lindholm (Including

English example) ... 63

Appendix 5: Advertisement Rachael Ray ... 65

Appendix 6: Advertisement Niclas Adler ... 67

Appendix 7: Advertisement Jan Björklund ... 69

Appendix 8: Advertisement Daniel Karlsson ... 71

Appendix 9: Advertisement James Blunt ... 73

Appendix 10: Advertisement Nikita Johnson (Local) ... 75

Appendix 11: Advertisement Nikita Johnson

(Well-known) ... 77

List of Tables

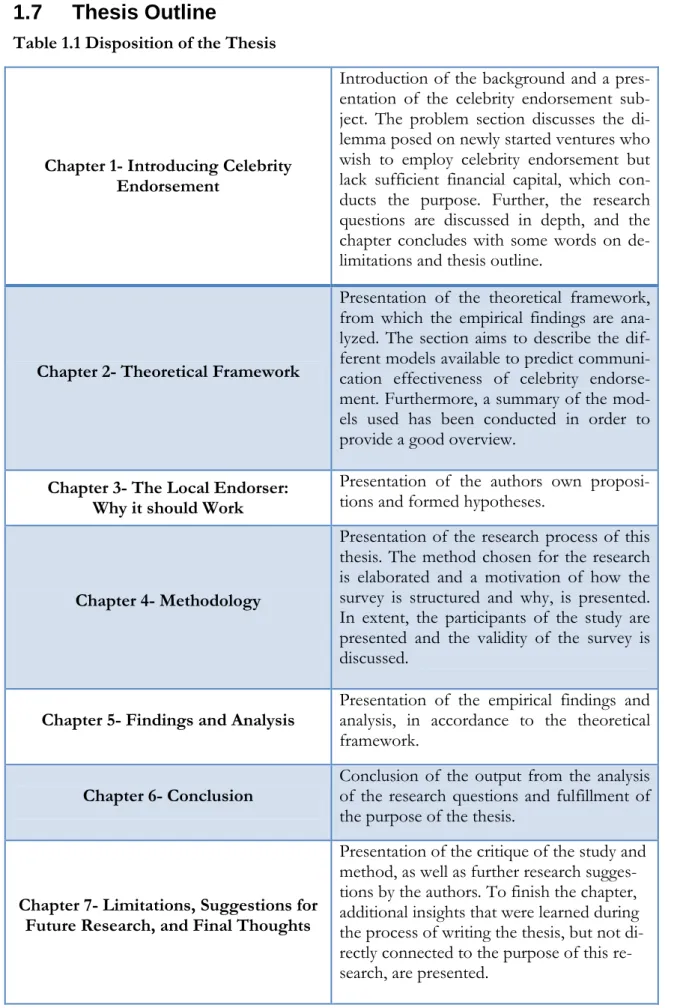

Table 1.1 -Disposition of Thesis 6

Table 2.1 -Summary of the Theoretical Models Covered 17

Table 4.1 -The Selected Celebrities for the Study 25

Table 4.2 -How Research Questions are Measured in the Survey 27 Table 5.1 -Mean Values for Local and Well-known Celebrity Endorsers 34

Table 5.2 -Statistical Results for Trustworthiness 36

Table 5.3 -Statistical Results for Expertise 36

Table 5.4 -Statistical Results for Attractiveness 37

Table 5.5 -Statistical Results for Emotional Involvement 38 Table 5.6 -Statistical Results for Celebrity-Product Association 39

Table 5.7 - Statistical Results for Image Transfer 39

Table 5.8 - Statistical Results for Communication Effectiveness 40 Table 5.9 - Statistical Results for Purchase Intentions 41 Table 5.10 -Statistical Results for Attitude towards the Advertisement 41

List of Figures

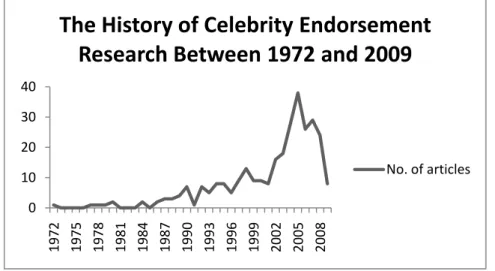

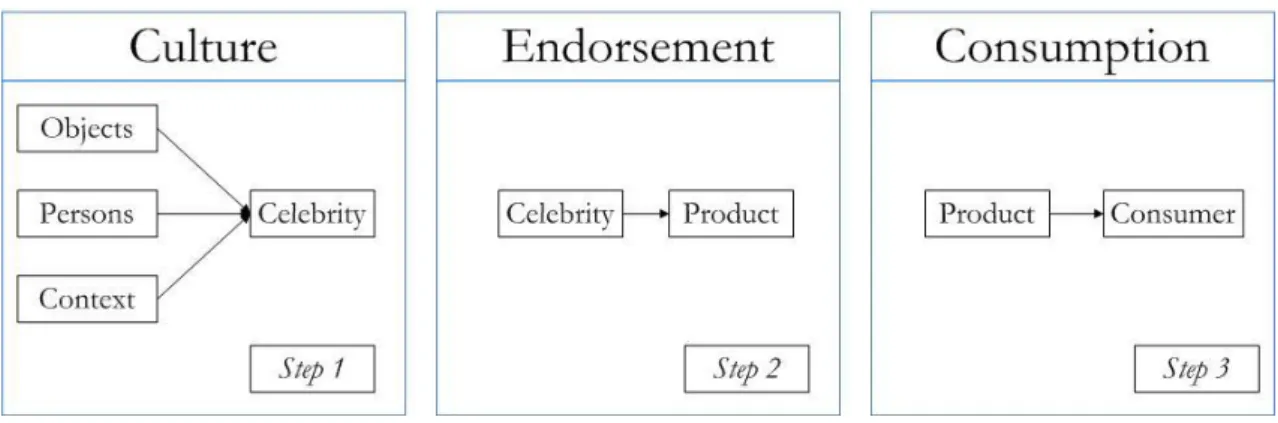

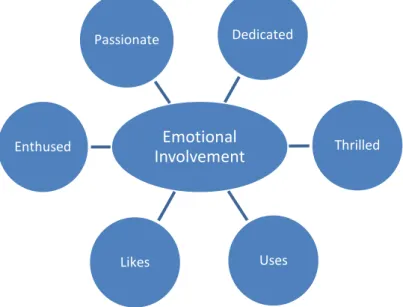

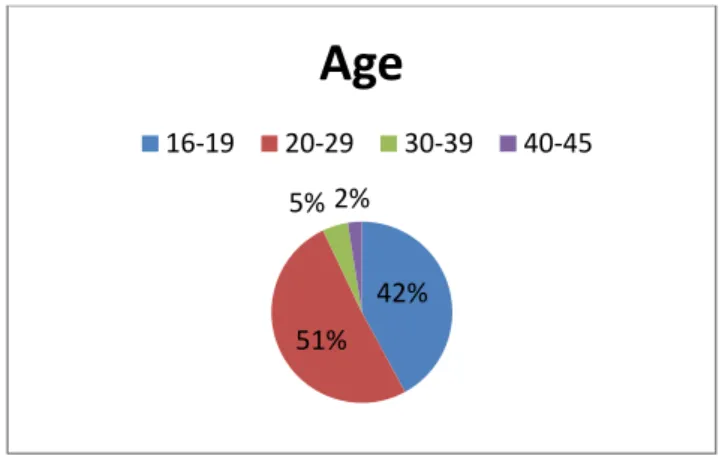

Figure 2.1 -Published articles from Google Scholar ranging between 1972 and 2009 7 Figure 2.2 -Meaning movement and the endorsement process 15 Figure 2.3 -The latent emotional involvement dimension and corresponding items 16 Figure 3.1 -Proposed model to test communication effectiveness 21 Figure 5.1 -Diagram showing the survey participants‟ age distribution 33 Figure 5.2 -The participants‟ gender distribution in the local celebrity group 34 Figure 5.3 -The participants‟ gender distribution for well-known celebrity group 34 Figure 5.4 -Diagram presenting the mean values of communication effectiveness 40

List of Pictures

Picture 2.1 -Johnny Cash 10

1

Introducing Celebrity Endorsement

This chapter introduces the background of this study and guides the reader into the subject of celebrity en-dorsement. The problem section discusses the dilemma posed on newly started ventures who wish to employ celebrity endorsement but lack sufficient financial capital, which conducts the purpose. Further, the research questions are discussed in depth, and the chapter concludes with some words on delimitations and the thesis outline.

1.1 Background to Study: Celebrity Endorsement, A Good but

Expensive Idea

New venture creation can today almost be seen as mesmerizing as rushing for gold was 1848-1855. The thought of becoming rich over night is capturing the masses, and striving to become an entrepreneur is probably more popular today than ever. Once a new venture is started however, it generally faces some difficulties that will not be overcome overnight. Stinchcombe (1965) introduces the argument that new organizations suffer from liability of newness, which means the higher propensity of younger organizations to die. This is com-posed of their dependence on the cooperation with strangers, low levels of legitimacy and inability to effectively compete with established organizations. Delmar and Shane (2004) further develop the concept of new ventures‟ lack of legitimacy. They propose that firms can reduce the hazard of organizational death and facilitate the transition to other organiz-ing activities by undertakorganiz-ing activities to generate legitimacy.

In order to survive, new ventures need to try to overcome the weaknesses of liability of newness and lack of legitimacy (discussed in section 2.1) as soon as possible. While many strategies to overcome these exist, one way to gain more attention, visibility and generate legitimacy is to use celebrity endorsement. The power of celebrity endorsement is captured in the following quote:

“Your client, whether they are an athlete or an actor or an actress, has intangible assets: a name, a reputa-tion, a credibility and an image. All of those attributes may be combined into something that could be made into a brand.” (Brian Dubin, quoted in Towle, November 18, 2003)

The celebrity endorser, as defined by McCracken (1989, p.310), is “any individual who en-joys public recognition and uses this recognition on behalf of a consumer good by appear-ing with it in an advertisement.” The use of celebrity endorsement in marketappear-ing communi-cation activities has risen remarkably. Solomon (2009) states that 20 percent of American advertisements feature celebrities. Even though celebrity endorsement in some cases can have negative consequences for the firm (Andersen, 1983; Marchand, 1985; Mehta, 1994; Ainsworth, 2007), most researchers agree that celebrity endorsement can, to differing de-grees, benefit the firm by increasing communication effectiveness (Kamen, Azhari, & Kragh, 1975; Friedman & Friedman, 1979; Atkin & Block, 1983; McCracken, 1989; Silvera & Austad, 2004; Forehand & Perkins, 2005). McCracken (1989), states that the attractive and likeable qualities of the endorsers are transferred to the products being endorsed. Cele-brities also create and maintain attention and achieve high brand name and advertisement recall rates (Friedman & Friedman 1979). Given that there is a good match between the endorser, product, and target audience, celebrity endorsers are more effective than non-celebrity endorsers in generating attitudes towards advertising and the endorsed brand, in-creasing purchase intentions, and inin-creasing sales (Erdogan 1999).

However, a major problem for new venture start-ups that has been ignored in this context is their lack of financial capital. Naturally, a lack of financial capital translates into problems of financing large celebrity endorsements. The price of endorsement contracts are not al-ways disclosed, but usually average between $200,000 and $500,000 (Johnson, 2005) and can reach up to $30 million (Talmazan, 2009).Even if large celebrity endorsements simply cannot be afforded, smaller celebrity endorsements may be. With this in mind, it can be of interest to investigate whether or not newly started ventures, with lack of financial capital, can benefit from investing in smaller celebrity endorsement. As it is argued later on, this thesis proposes that local celebrity endorsement can be at least as effective as well-known celebrity endorsement in overcoming liability of newness and lack of legitimacy. In this context, local celebrity endorsement can be generated by using celebrities famous in a smaller geographical region, a certain market, industry, community or other niche.

1.2 Problem Discussion

The field of celebrity endorsement already enjoys academic attention. However, a subfield has been detected which is yet to be researched. New ventures often suffer from liability of newness and lack of legitimacy (Stinchcombe, 1965; Delmar & Shane, 2004). Therefore, they find themselves in the need to create fast reputational capital (defined in 1.6). New ventures urgently need to create attention, interest, respect and demand. This is important today, when the environment of competing for attention is more severe than ever. For newly started ventures, this environment is even tougher due to the lack of adequate mone-tary capital (Schaefer, 2006). Therefore, it could be of interest to investigate whether or not the wanted attention can be gained effectively, without large sums of money.

One way for businesses to create reputational capital is through the use of celebrity en-dorsement (Hunter, Burger & Davidsson, 2008). The aim is to transfer some of the celebri-ty‟s image and brand to the business (McCracken, 1989). However, the problem is since newly started ventures often lack sufficient financial capital, they cannot afford to use ex-pensive celebrity endorsement. This thesis tries to solve this problem by investigating if lo-cal, and therefore cheaper, celebrity endorsement may be as effective as well-known celebr-ity endorsement. Until now, research has focused on other themes. There are extensive studies covering whether or not celebrity endorsement is beneficial (Agrawal & Kamakura, 1995) and cases where celebrity endorsement can have negative effects on the brand (Shimp & Till, 1998; Farrell, Karels, Montfort, & McClatchey, 2000). Other studies focus on what determines the communication effectiveness of the endorsement (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Hovland, Janis & Kelly, 1953; Kahle & Homer, 1985; McGuire, 1985; McCracken, 1989). However, no study so far focuses on the theme of this thesis. There-fore, the study is conducted by combining general theory of celebrity endorsement with the performance of a study consisting of widely distributed surveys with manipulated variables. This study is significant since the specific topic has not been researched previously, and it may be of great value for new ventures that find themselves in the described situation. If it is found that local celebrity endorsement is as effective, this can open up many opportuni-ties for new ventures, as well as other financially constrained firms, to explore.

1.3 Purpose: Investigating Communication Effectiveness of

Local and Well-known Celebrity Endorsement

This thesis aims to investigate whether a local, and therefore a lot less expensive celebrity, might be an as effective endorser as a well-known celebrity, given the right contextual set-ting.

By researching the effect which local and well-known celebrity endorsement can have on the communication effectiveness of newly started ventures, the authors wish to make an important theoretical contribution.

The key research purpose of this thesis is to:

Investigate the impact of local and well-known celebrity endorsement on communication effectiveness.

1.4 Research Questions

This thesis investigates whether or not local celebrity endorsement can be as effective as well-known celebrity endorsement. In order to fulfill this, the following research questions are developed:

1. Can local celebrity endorsers be viewed at least as credible as well-known celebrity endorsers? 2. Are local celebrity endorsers perceived equally attractive as well-known celebrity endorsers? 3. Can local celebrities be perceived at least as emotionally involved in the endorsement process as

well-known celebrities?

4. Can local celebrities be as capable of transferring meaning to the endorsed product as well-known celebrities?

The research questions are further discussed and developed along with related literature and formed hypotheses in sections 2.3 and 2.4.

1.5 Delimitations

The focus of this thesis is the effectiveness of local celebrity endorsement, used by newly started ventures that target local markets. Due to time constraints, the authors were re-stricted in their choice of method. More specifically, the survey is only made available in eight versions. This number could have been higher if more time had been available. Also due to time constraints, the base of the study is restricted to Jönköping, Sweden and the participants are all located within the Jönköping area. Additionally, because the authors had financial limitations, the advertisements presented in the surveys are made by the authors, not a graphic designer.

1.6 Definitions of Concepts

This part presents the frequently used concepts according to occurrence, to facilitate com-prehension of the thesis.

Endorser:

There are different types of endorsers; celebrities, experts, and typical consumers (Fried-man & Fried(Fried-man, 1979). The celebrity endorser is discussed in the definition below. The expert is an individual or a group that has acquired superior knowledge concerning the en-dorsed product class. This expertise is gained through education, training or experience (Friedman & Friedman, 1979). Friedman and Friedman (1979) argue that the typical con-sumer, who is an average person, also can act as an endorser. This person is assumed to represent an individual in everyday life, with no previous experience of the product class. An endorser can also be called a spokesperson, human brand, et cetera. Basically, it is someone who expresses their support toward a brand or a product.

Celebrity Endorser:

A celebrity is in general someone who is widely known for something they have achieved. The celebrity can, for example, be a sports figure, actor or entertainer (Friedman & Fried-man, 1979). It can be anyone who is recognized by the public (McCracken, 1989).

As mentioned above, a celebrity is someone who is acknowledged by the public. This fa-mous individual will, as an endorser, use their recognition and transferring it to a product or a service through advertisements (McCracken, 1989). By using an endorser, companies hope to use the endorser‟s personality and personal values to gain attention from the public (Knott & James, 2004).

Local Celebrity:

The definition of the word local is according to Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary “primarily serving the needs of a particular limited district”. The local celebrity can be fa-mous within a society, niche, industry or market. Examples of local celebrities can be news reporters, politicians, religious leaders, popular bloggers or famous radio DJ:s. It can also be a chef at a well-known restaurant, an anchorman or a social figure.

An example of a local celebrity is the locally known singer from Uddevalla, Sweden; Lasse Matilla. A more well-known celebrity in this example is the Swedish singer Timbuktu, who is widely known all over Sweden. Another example of a local and a well-known celebrity is Tina Nordström and Martha Stewart. The first mentioned is a chef who is famous in the Swedish cooking world. Martha Stewart is famous in the same niche, but in an international perspective.

An endorser is someone who “…recommend[s] (as a product or service) usually for financial compensation” (Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary).

One definition of a celebrity is someone who is in “the state of being well known” (The Oxford Pocket Dictionary of Current English).

A local celebrity is in this thesis defined as someone who is famous within a region, city or culture.

Well-Known Celebrity:

It can, for example, be an internationally known movie star, singer, athletic star or enter-tainer. This type of celebrity often has a large influence on the public. A well-known celeb-rity receives extensive attention in the media and can be known globally. Some parts of the public can even be obsessed with the internationally well-known celebrities (Maltby, Day, McCutcheon, Martin & Cayanus, 2004).

Reputational Capital:

Reputational capital is the perceptions and associations made by the consumers about the company (Suh & Amine, 2007). Reputational capital can also be known as „corporate per-sonality‟ and „corporate reputation‟ (Suh & Amine, 2007). By having a good reputation, the firm stabilises customer demand for its services or products (Jackson, 2004).

Celebrity Capital:

Celebrity capital is also known as celebrity equity (Louie, Kulik & Jacobson, 2001). Com-panies hope to transfer the celebrity‟s favourable awareness and associations to the brand or product. Since newly started companies often lack reputational capital (Stuart, Hoang & Hybels, 1999; Delmar & Shane, 2004) they can use the reputation of others, such as celeb-rities, to improve their reputation (Rao, 1994; Yiu & Lau, 2008). When using celebrity capi-tal a company desires to increase its market position by strengthening its brand. The inten-tion of using celebrity capital is to create positive reacinten-tions and attitudes among the target audience. It is also used to increase attention and transfer the celebrity‟s image to the prod-uct and the character of the good (O Mahony & Meenaghan, 1998).

Communication Effectiveness:

The desired communication outcome is often to prompt action, in this case increased pur-chase intentions (Drogan, 2006). In this thesis, communication effectiveness refers to how successful an endorser is in communicating the message of the advertisement and brand to the public. If the message is successfully conveyed, it should translate into positive attitudes toward the brand, and increased purchase intentions. Communication effectiveness can therefore, from the company‟s side, most easily be measured by increased purchases. This could be done, for example, by comparing revenues before and after an advertisement campaign.

A well-known celebrity is defined as someone who is famous worldwide or nation-wide.

Communication effectiveness can be described as the degree to which the desired communication outcome is achieved (Drogan, 2006).

Jackson (2004) defines reputational capital as an intangible asset that is intended to generate profit in the long run.

Celebrity capital consists of a celebrity‟s past behaviour, reputation, public awareness, their favourability and personality (Hunter et al., 2008).

1.7 Thesis Outline

Table 1.1 Disposition of the Thesis

Chapter 1- Introducing Celebrity Endorsement

Introduction of the background and a pres-entation of the celebrity endorsement sub-ject. The problem section discusses the di-lemma posed on newly started ventures who wish to employ celebrity endorsement but lack sufficient financial capital, which con-ducts the purpose. Further, the research questions are discussed in depth, and the chapter concludes with some words on de-limitations and thesis outline.

Chapter 2- Theoretical Framework

Presentation of the theoretical framework, from which the empirical findings are ana-lyzed. The section aims to describe the dif-ferent models available to predict communi-cation effectiveness of celebrity endorse-ment. Furthermore, a summary of the mod-els used has been conducted in order to provide a good overview.

Chapter 3- The Local Endorser: Why it should Work

Presentation of the authors own proposi-tions and formed hypotheses.

Chapter 4- Methodology

Presentation of the research process of this thesis. The method chosen for the research is elaborated and a motivation of how the survey is structured and why, is presented. In extent, the participants of the study are presented and the validity of the survey is discussed.

Chapter 5- Findings and Analysis Presentation of the empirical findings and analysis, in accordance to the theoretical framework.

Chapter 6- Conclusion Conclusion of the output from the analysis of the research questions and fulfillment of the purpose of the thesis.

Chapter 7- Limitations, Suggestions for Future Research, and Final Thoughts

Presentation of the critique of the study and method, as well as further research sugges-tions by the authors. To finish the chapter, additional insights that were learned during the process of writing the thesis, but not di-rectly connected to the purpose of this re-search, are presented.

2

Theoretical Framework

In this section the theoretical framework is presented, from which the empirical findings are analyzed. The section aims to describe the different models available to predict communication effectiveness of celebrity en-dorsement. Furthermore, a summary of the models used has been conducted in order to provide a good over-view.

Celebrity endorsement, as it is known today, was first introduced in the early 1970s. Since then, it has been applied as well as researched extensively. This graph shows that the inter-est of celebrity endorsement has increased and gained more attention during the last ten years.

Figure 2.1 Published articles from Google Scholar ranging between 1972 and 2009, collected by the authors using the keyword „celebrity endorsement‟ Due to its popularity, the research on celebrity endorsement has focused on numerous amounts of different themes which are brought up later in the chapter. The following sec-tions guide the reader through the general topics of celebrity endorsement, describe the dif-ferent models applied and introduce the concept of local celebrity endorsement; which has not been academically researched and tested before.

2.1 Choice of Theory

There are many theories employed in celebrity endorsement research. The theories used in this thesis are chosen since they are well known and often used in the area of celebrity en-dorsement. There are some similar theories that overlap each other, such as the match-up hypothesis and the meaning transfer model. The match-up hypothesis is used in this thesis to complement the statements of the meaning transfer model and employed in the process of matching the celebrities with the respective products for the survey.

The following sections present the theory chosen to illustrate the problem statement of this thesis, namely that newly started ventures who wish to use celebrity endorsement as a way to gain reputational capital, most often cannot afford it.

0 10 20 30 40 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008

The History of Celebrity Endorsement

Research Between 1972 and 2009

2.1.1 The Importance of Reputational Capital

It is crucial for companies to be well known and to have a good reputation in order to be able to compete with other firms. According to Jackson (2004), reputation is everything in today‟s society. Often, before deciding which company to invest in or from what company to buy products, presumptive buyers tend to gather information about the competing firms. However, sometimes they find it difficult to gather enough information. In these cases consumers usually compare the different companies‟ reputations to make their deci-sion process easier. Jackson (2004) defines reputational capital as an intangible asset that is intended to generate profit in the long run. Petrick, Scherer, Brodzinska, Quinn and Ainina (1999) argue that it is time consuming to build a reputation, especially for newly started companies.

Even though the process of building a reputation is time consuming, a firm‟s reputation is very fragile. Damaging the reputation can be easily and quickly done (Petrick et al., 1999). An example of such an incidence is when the car company Toyota used the celebrity Mi-chael Irvin from Dallas Cowboys as their endorser. In 1996, Irving was caught by the po-lice with prostitutes and drugs. This action affected Toyota remarkably, since the company had planned to use Irving in a series of advertisements worth $500,000. Only thirteen Toyota dealerships survived this event. Toyota did not only lose trust from the public, the company also lost the money it had invested in the Dallas Cowboys star and had to find a new alternative for Irving, which meant even more expenses (Lane, 1996).

Reputational capital measures the trustworthiness, reliability, credibility, responsibility and accountability of a company (Petrick et al., 1999). An effective way to gain reliability is to guarantee service, innovation and quality. Reputational capital is an important factor, and when used properly it can help companies in the process of obtaining great benefits and competitive advantage (Petrick et al., 1999; Jackson, 2004). Other companies will consider firms with a positive reputational capital that stress its fair play and honesty, as a potential strategic partner. Furthermore, Jackson (2004) states that good reputation often results in customer loyalty. By having a good reputation a firm stabilises customer demand for the firm‟s services or products.

2.1.1.1 Reputational Capital for Newly Started Ventures

For newly started firms it is important to build a good reputation fast (Székely & Sabot, 1997). A company cannot start from scratch and expect to be able to sell its stock or bonds to the public right away. The company needs to gain customer trust and prove itself trust-worthy and reliable. This can take years to obtain and is not easily done (Székely & Sabot, 1997).

2.1.1.1.1 Liability of Newness

Newly started companies suffer a higher risk of failure than more established and skilled firms. New businesses will most likely lack the expertise that these firms posses (Stinch-combe, 1965). Moreover, established firms usually have complementary assets organised, that newly started organisations do not have (Teece, 1986). As mentioned previously, a firm‟s reputational capital is often a factor that determines if a firm is seen as a potential business partner. This is disadvantageous for newly started firms since they initially lack re-putational capital (Delmar & Shane, 2004; Stuart et al., 1999). Newly started ventures do not have any existing relationships with suppliers or customers, which makes it difficult for them to compete with established firms (Stinchcombe, 1965). Since newly started ventures are not seen as liable as established firms, it is essential for them to build an awareness of

being legitimate. If they do not, it is difficult to endure the competition from established companies (Delmar & Shane, 2004). Newly started ventures should quickly develop rou-tines within the organization to be able to compete with other firms (Delmar & Shane, 2004).

2.1.1.1.2 Lack of Legitimacy

Stinchcombe (1965) argues that legitimacy is a social judgment of appropriateness, desira-bility and acceptance. Stinchcombe also states that legitimacy makes it possible for compa-nies to gain access to other resources. Legitimacy can be used in a strategic way to help companies increase resources and growth (Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002). Gaining legitimacy helps newly started firms to overcome the liability of newness (Stinchcombe, 1965). Re-searchers argue that legitimacy is one of the most important factors for new venture sur-vival. Zimmerman and Zeitz (2002), state that legitimacy is present in every company that has survived its start-up.

Legitimacy is described as the equivalence between norms, values, and expectations of so-ciety, and performance of the organization (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975; Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990). To gain legitimacy a newly started company must prove itself desirable by engaging itself in things seen as legitimate; such as respecting rules, undertaking values and norms in its field and demonstrating competence (Shepherd, 1999). Zimmerman and Zeitz (2002) believe that fewer companies would fail if they managed to acquire, build and use legitima-cy even before the start-up. Hunter et al. (2008) claim that when using a celebrity endorser, the company might gain legitimacy through the celebrity‟s reputational capital. As celebrity endorsers are well known and often seen as trustworthy, this might be reflected in the new-ly started venture. By using celebrity capital they can be perceived as a more legitimate and reliable company by potential business partners (Hunter et al., 2008). People are usually not willing to purchase products where they lack knowledge. Even if some people do know about the products, they are skeptical towards newly started firms since they lack credibili-ty. Customers do not know whether the firm will deliver products with good quality or not (Glynn, Motion, & Brodie, 2007).

2.1.1.1.3 Lack of Financial Capital

Statistics state that only two-thirds of new ventures survive more than two years, and 44 percent stay alive for more than four years (Schaefer, 2006). Schaefer (2006) describes sev-en pitfalls for newly started firms; 1) You start your business for the wrong reasons, 2) Poor management, 3) Insufficient Capital, 4) Location, Location, Location, 5) Lack of Planning, 6) Overexpansion, and 7) No website. Number three on this list is insufficient capital, which shows the importance of funding a newly started venture.

According to Cooper and Gimeno-Gascon (1991), there is a relationship between the initial amount that is invested in the newly started firm and the performance of the firm. Out of eight former studies that investigated this relationship, six of the cases performed better when the initial capital was higher. For example, more financial capital will allow a firm to buy more assets. Cooper and Gimeno-Gascon (1991) also state that higher initial financial capital will increase the possibilities of survival, since the owner can afford to make mis-takes and have time to figure out solutions to problems that might occur. A common rea-son for the lack of financial capital is an underestimation of the money needed. This might force the end of a newly started venture. Funds to cover the first couple of years may be needed, since many newly started ventures take a year or two before the business can

sur-vive on its own profits (Schaefer, 2006). If the new venture wishes to invest in a marketing strategy, such as celebrity endorsement, it is essential to have sufficient financial capital since it is expensive (Talmazan, 2009).

2.1.2 Celebrity Endorsement in Depth

The phenomenon of celebrity endorsement is widely used today. As mentioned previously, Solomon (2009) states that celebrity endorsement is present in 20 percent of all American advertisements. However, what many people do not know is that celebrity endorsement has been present since the nineteenth century. At that time, the celebrities used for en-dorsements were royalties. Nevertheless, the intentions regarding the strategy of achieving recognition and increasing value to the product through customers‟ social desires, were the same as today (Almquist & Roberts, 2000).

Due to a strong development of the media and an increase in number of famous people, celebrity endorsement has grown. One major event in the beginning of the 1970s which is said to have changed advertising strategy was when Johnny Cash appeared in Amoco (also known as American) Oil‟s commercials. This was the first time a person from the enter-tainment industry, who was known nationwide, endorsed a company. Amoco Oil knew be-fore it chose Johnny Cash as endorser that there were risks, since motorists already op-posed Cash no matter of his prior popularity and familiarity. Nevertheless, Amoco Oil de-cided that the benefits from using Cash were more than the negative attention he con-veyed. As Amoco Oil expected, soon after Cash‟s first commercials the company received hundreds of letters, which were mainly negative. However, the marketing management de-partment believed in their choice and was confident that if only the motorists got familiar with Cash, their negativity would decline (Kamen et al, 1975).

1

Since its beginning, when used correctly celebrity endorsement is proven to be advanta-geous (Friedman &Friedman, 1979; McCracken, 1989; Silvera & Austad, 2004; Forehand & Perkins, 2005). An important aspect of this marketing strategy that must be considered wisely is the selection of endorser. Friedman and Friedman (1979) performed a study where three endorser types were compared; celebrity, expert, and typical consumer. They surveyed the different endorsers with different products to design the most effective match up. The conclusion made by the study was that celebrities work best, with some exceptions.

1 Picture: Johnny Cash, retrieved 2010-0318, from http://zishan.com/Amoco/

For instance, if the product is complex and high in financial, performance or physical risk, it is better to choose an expert endorser.

Another strategy that can be used by companies when deciding on whom to endorse its products is the match-up hypothesis (Kamins, 1990; Misra & Beatty, 1990; Till & Busler, 1998). The match-up hypothesis concerns the fit between the endorser‟s image and the product or brand. The hypothesis suggests if the fit between the endorser and product is successful, the endorsement will be more effective. A fit between these two also implies that the celebrity endorser‟s image matches the product‟s characteristics (Kamins, 1990;

Misra & Beatty, 1990, Till & Busler, 1998). Many studies claim that different attributes of the celebrity will affect the outcome of an endorsement. Kamins (1990) performed a study in relation to the physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser to establish if an attractive endorser is more effective than an unattractive endorser. Kamins (1990) concluded that physically attractive celebrity endorsers are more effective in a particular product group (especially vanity related products). For other types of products there is no difference of influence between the physically attractive and unattractive celebrity endorser.

Celebrity endorsement is effective, especially if the intention is to increase awareness (Alm-quist & Roberts 2000). Nevertheless, the effectiveness may vary due to positive and nega-tive variables that must be considered as trade-offs when choosing the strategy (Kamen et al., 1975). One positive aspect of celebrity endorsement is that positive feelings towards the celebrity endorser may be transferred to the endorsed product. Another positive effect is the possibility of free advertisement through the celebrity in question and their spotlight, when they appear in other contexts (Silvera & Austad, 2004). When reviewing prior re-search it is safe to say that celebrity endorsement is a successful concept when used proper-ly and when the endorser is matched-up with a product well-suited for them.

2.1.2.1 Risks Associated with Celebrity Endorsement

When a company uses celebrity endorsement, there are certain risks that should be consi-dered. These risks are described in this section.

When a celebrity endorses a product or brand, a link between the two is formed that relates the image of celebrity on to the product or brand and vice versa (Andersen, 1983). If nega-tive information is revealed about the endorser it might reflect neganega-tively on to the brand the celebrity is endorsing and transfer the negativity from the celebrity toward the brand (Andersen, 1983).

If the celebrity „over-shines‟ the endorsed product, the targeted customers will only recall the spokesperson, not the product or brand itself. This is called the vampire effect where the “celebrities suck the life-blood out of the product dry” (Evans 1988, as cited in Erdogan, 1999, p. 303). A different risk connected to the just mentioned problem is if a celebrity en-dorses multiple products (Marchand, 1985). This may confuse audiences, who might have trouble connecting the celebrity with a particular brand, hence ruining the purpose of cele-brity endorsement. Another risk that is impossible to control is controversial behavior by a spokesperson that might damage the image of the endorsed brand (Marchand, 1985). There are recent studies regarding the effects arising when negative information about a ce-lebrity endorser is revealed (Ainsworth, 2007). Ainsworth (2007) tested to which extent young customers are affected by negative information concerning a celebrity endorser. The study suggests that companies choosing celebrity endorsement need to worry more about the strength of association between a product or brand and the celebrity, rather than the negative information that can be revealed about the celebrity. Ainsworth (2007) continues

to argue that customers may not be turned off from a product or brand simply if a celebrity endorser is involved in a controversial incident. However, the nature of the controversy will have an impact on the consumer base; rape and murder accusations are such occur-rences that definitely would turn customers away from a product or brand.

2.1.2.1.1 Controversial Celebrity Endorsers

There are few possibilities for companies to control the behavior of their endorsers, ac-cording to Marchand (1985), and there are many examples of celebrity endorsements that have gone terribly wrong. One endorsement incident that definitely could not be controlled was when James Garner, who was a spokesperson for beef, had a heart attack resulting in a triple bypass (Trout, 2009). This was probably not the message that the beef company wanted to portray. Other endorsement deals that went down the drain involved Kobe Bryant. Bryant was endorsing McDonalds, Sprite, and Nutella when he was charged with sexual assault (Trout, 2009). Once again, probably not the message these companies wanted to portray.

Celebrity endorsement can also fail since there is no assurance that the spokesperson stays faithful to the company. One example of this is when the former tennis star Martina Hingis promoted an Italian sneaker company that also made tennis-gear. This endorsement was working smoothly until Martina Hingis sued the Italian company claiming that the gear it provided caused her injuries (Trout, 2009). A current major endorser who has made a lot of money from endorsement contracts is Tiger Woods (Farrell & Van Riper, 2008). The massive endorser and golf-professional, Tiger Woods, was recently involved in a sex-scandal where it was revealed that he had cheated on his Swedish wife, Elin Nordegren. When the scandal was exposed there were discussions on how his troublesome personal life would affect his lucrative endorsement deals (Gregory, 2009; Talmazan, 2009). The risks the companies face from staying with Woods could escalate if other scandals unwrap involving the golf champion and have dreadful consequences for the companies.

If the choice of implementing celebrity endorsement in the marketing strategy is made, Till and Shimp (1998) argue that there is no possibility for the companies to control the celebri-ty‟s future behavior. Any negative news regarding the celebrity might decrease the appeal of the celebrity, hence transfer negative feelings towards the endorsed brand. Furthermore, the risk is greater for newly started firms rather than well-known established brands (Till & Shimp, 1998).

2.1.2.2 2The Hefty Price Tag of Celebrity Endorsement As stated throughout this thesis, celebrity endorsement is a phenome-non that is increasing. However, the average compensation paid to spokespersons is also increasing (Agrawal & Kamakura, 1995). Some celebrities, such as Tiger Woods, today earn more money as a spokes-person than in their original profession (Farrell, 2008). Even though the average profitability from the usage of celebrity endorsement is high, the original investment is costly for the company (Agrawal & Kamakura, 1995). Depending on the celebrity, the endorsement could cost millions of dollars over a period of many years. The infamous

2Picture: Tiger Woods, retrieved from

http://mcsearcher.wordpress.com/2009/09/13/tiger-woods-waal-papers/

model Linda Evangelista made a remarkable statement regarding the payment she de-mands: "I won't get out of bed for less than $10,000 a day" (Supermodelguide.com). Another celebrity with a high price tag for taking part in commercials is Christy Turlington. She endorsed Maybelline‟s products for a mere $3 million, which only involved twelve days of work a year (Supermodelguide.com). Tiger Woods, who earns $100 million a year through endorsement contracts, certainly has a high price on his endorsement skills. To mention a few, his deals include a $30 million contract with Nike, $20 million with Accen-ture, and $15 million with Gillette (Talmazan, 2009). Studies have been conducted to test whether the large investment of celebrity endorsement is a wise decision or not, and have shown both positive and negative results. However, the average outcome is that investing in celebrity endorsement is a profitable strategy (Agrawal & Kamakura, 1995).

2.1.2.3 Celebrity versus Non-Celebrity Endorsers

Even though there has been many studies proving the effectiveness of celebrity endorse-ment, given that the match between celebrity and product is successful (Kamen et al., 1975; Friedman & Friedman, 1979; Atkin & Block, 1983; McCracken, 1989; Silvera & Austad, 2004; Forehand & Perkins, 2005), there are studies questioning the use of celebrities in ad-vertising (Mehta, 1994; Almquist & Roberts, 2000). These studies question whether a cele-brity endorser is better than a non-celecele-brity endorser. If a company creates a character, typ-ically with an anonymous model, to represent its products in advertisements, it can have to-tal control over the endorser. The company can freely assign preferred characteristics de-sired for the brand. If a celebrity is chosen as endorser, the match-up with the product is what will make or break the advertisement (Tom, Clark, Elmer, Grech, Masetti & Sandhar, 1992). There are researches in both directions; however, the majority supports celebrity en-dorsement rather than non-celebrity enen-dorsement. Mehta (1994) suggests that there may be more focus on the celebrity rather than the endorsed product or brand. Atkin and Block (1983) suggest in their study that celebrity endorsement is more effective on teenagers; however, celebrities in advertisements are apprehended as more competent and trustwor-thy than non-celebrity endorsers in all age groups. The study also confirms that a more positive reaction will be present towards an advertisement starring a celebrity than an iden-tical advert with a non-celebrity. The celebrity endorser is described as strong, interesting, effective, and important. Other studies show that celebrity endorsers attract more attention to an advertisement since there is a massive stream of messages for consumers to filter (Kamen et al., 1975).

2.2 Choosing the Right Celebrity

When firms search for a celebrity to endorse their brand, their aim is for the communica-tion effectiveness to be as high as possible. Choosing the right celebrity is the first crucial step in the endorsement process, which makes it important to do so with care (Kamins, 1990; Misra & Beatty, 1990). Previous research has established various models that provide the tools to predict communication effectiveness of a possible endorsement (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Hovland, et al., 1953; Kahle & Homer, 1985; Ohanian, 1990; Erdogan, 1999; Hunter et al., 2008; Hunter, 2009). These models can guide firms in the process of finding and choosing the right celebrity that matches their brand. This section will summarize the source models, the meaning-transfer model and the concept of emotional involvement.

2.2.1 The Source Models

„The Source Models‟ refer to two models; namely source credibility model and source at-tractiveness model. These models originate from the study of communications (Ohanian,

1990), but have later become common models applied in the field of celebrity endorse-ment. Both models aim to determine under which conditions the source, in this case the endorser, is persuasive and influences attitude and opinion change (Erdogan, 1999; Hunter, 2009).

2.2.1.1 Source Credibility Model

The source credibility model implies that potential consumers are more open to persuasion when the source, in this case the endorser, presents itself as credible (Hovland, et al., 1953). The source credibility model demonstrates that the communication effectiveness of a mes-sage depends on the perceived level of trustworthiness and expertise of the endorser (Hov-land & Weiss, 1951; Hov(Hov-land et al., 1953). Hov(Hov-land et al. (1953) assume that if communica-tors are perceived trustworthy and show expertise, they are seen credible, and therefore persuasive.

2.2.1.1.1 Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness refers to the perceived honesty, integrity and believability of the endorser. Ohanian (1990) maintains that the value of trustworthiness can be capitalized by employing endorsers who are alleged as being honest, reliable, sincere and dependable.

2.2.1.1.2 Expertise

Expertise is defined as the ability of the source to make truthful statements. Expertise con-sists of the possession of knowledge, experience and skills (Erdogan, 1999). The value of expertise can be capitalized by employing endorsers who are alleged as being experienced, knowledgeable, qualified and skilled (Ohanian, 1990).

2.2.1.2 Source Attractiveness Model

Although attitude change may often be related to physical attractiveness of a celebrity (Kahle & Homer, 1985), attractiveness in this sense does not only refer to physical appear-ance. It includes all characteristics that a consumer may view as attractive in an endorser. These may be characteristics such as intellectual skills, personality properties, lifestyle, or athletic ability (Erdogan, 1999). Research has shown that attractive endorsers are more fective communicators than unattractive endorsers. The McGuire model states that the ef-fectiveness of the message depends on the familiarity, similarity and likeability of the source (McCracken, 1989). McGuire (1985) assumes that if communicators are perceived to hold these attributes, they are seen attractive by consumers, and therefore persuasive. Familiarity is here defined by McGuire (1985) as knowledge of the endorser, similarity as the seeming resemblance between the endorser and the consumer, and likeability as affection for the endorser as a result of their physical appearance and behavior.

2.2.2 Comments on the Source Models

The source models have been researched and confirmed in many studies (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Hovland, et al., 1953; Kahle & Homer, 1985; Erdogan, 1999; Hunter et al., 2008; Hunter, 2009) and it may be safe to say that the communication effectiveness of ce-lebrity endorsement activities to some extent relies on the credibility and attractiveness of the source. However, these models have been criticized (McCracken, 1989 & Hunter, 2009) for not portraying all the elements that determine communication effectiveness. In the light of this, the alternative meaning transfer model and the concept of emotional involvement will be introduced to complement the source models.

2.2.3 The Meaning Transfer Model: Cultural Meaning and the Celebrity Endorser

As already established, the effectiveness of celebrity endorsement can be explained in many different ways. According to the meaning transfer model as developed by McCracken (1989) in criticism to the source models, the effectiveness of celebrity endorsers depends on the cultural meanings which they encompass and the meanings they bring to the en-dorsement process. The model both shows how meaning is transferred from celebrity to product and from product to consumer (see figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Meaning movement and the endorsement process, adapted from McCracken (1989) Celebrity endorsers differ in gender, age, status, personality and lifestyle types (McCracken, 1989). These characteristics combine to produce a myriad of different meanings available for the marketer to employ in the endorsement process. The celebrity world has all types to offer; such as the careless young partygoer Paris Hilton, the mature philanthropist Angelina Jolie, the „crazy slob‟ Jack Black and the unreliable heartbreaker Charlie Sheen. By this, McCracken (1989) makes a point that the celebrity world contains more than simply „credi-ble‟, „attractive‟ and „expert‟ individuals. McCracken states that the best endorsements stem from successful meaning transfers.

In practice, the meaning transfer process begins with the advertiser choosing what mean-ings to attribute to the product (McCracken, 1989). Basically any meanmean-ings can be decided, depending on the marketing plan. Well created advertisements succeed in conveying these meanings to the consumer. Celebrity endorsers contribute to this process by letting their own cultural meanings be ascribed to the product, which is later transferred to the con-sumer. It is important to point out that celebrities are much more successful in delivering meanings to the product, than the anonymous model that otherwise might be used to bring meaning to an advertisement (Kamen et al., 1975). Celebrities can convey their meanings with more precision and can offer their ranges of already well-known personality and life-style meanings that an anonymous model cannot. It is important that the advertisement is created to show similarities between the celebrity and product, so that these meanings can be easily absorbed and accepted by the consumer (McCracken, 1989).

To conclude the discussion of the meaning transfer model, it should be noted that the model does not disregard the source model concepts of credibility, expertise and attrac-tiveness. It merely shifts the debate and considers credibility not in terms of the manner in which celebrities communicate a message, but the manner in which celebrities communicate a meaning. This also suggests that a celebrity may be extremely credible for transferring some meanings, but may be much less credible for other meanings (McCracken, 1989).

Emotional Involvement Dedicated Thrilled Uses Likes Enthused Passionate 2.2.4 Emotional Involvement

So far, it has been expressed that the communication effectiveness of a celebrity endorser depends on its trustworthiness, expertise (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Hovland et al., 1953), attractiveness (McGuire, 1985) and meaning transferred to the product (McCracken, 1989). „Emotional Involvement‟, as suggested by Hunter (2009), is an additional concept to also be categorized as a measure of credibility. “Perceived Emotional Involvement measures in-ferences being made about the endorser‟s attitude towards the product and attitude to-wards working with the product” (Hunter, 2009, p.44). Hunter proposes that higher per-ceived emotional involvement increases the communication effectiveness of celebrity en-dorsement.

Emotional involvement refers to a celebrity endorser‟s motivation to be part of the adver-tisement. The individual terms that compromise emotional involvement are: like and use, which measure a celebrity‟s attitude towards the product, and passion; enthusiasm; dedica-tion and being thrilled which measure a celebrity‟s attitude towards working with the prod-uct (Hunter, 2009).

“Many consumers said they like seeing celebrities whom they think really use the products – especially if the ad is funny.” (The NPD Group/Celebrity Influence Study, May 2006)

2.2.5 Summary of Models

The models described above have been chosen as the theoretical foundation to base the investigation on.

Table 2.1 Summary of the Theoretical Models Covered

Model Focus Celebrity

characte-ristics Implications

Source Credibility Trustworthiness and

expertise

Honest, reliable, sin-cere, dependable, ex-perienced,

knowledge-able, qualified and skilled

The celebrity should be perceived as being

a credible source of truthful statements

Source

Attractive-ness Attractiveness Familiar, similar and likeable

The celebrity should be perceived attractive

by the consumers

Meaning Transfer

Compatibility

Holds compatible identi-ty,

personality and life-style

There should be com-patibility between the brand and the

celebri-ty

Emotional

Involve-ment Motivation

Perceived to like and use the product, show

passion, enthusiasm, and dedication and

be-ing thrilled about the collaboration

Make sure that the ce-lebrity is motivated to work with the product and appear in the

3

The Local Endorser: Why it should Work

This chapter presents the authors own propositions and hypotheses formed.

So far, the presented previous research has established that in order for a celebrity endorser to be effective in their communication, they should be perceived as trustworthy, expert and attractive. They should also be perceived as being emotionally involved in the endorsement process. Further, it is important that there is a successful meaning transfer between the ce-lebrity and product, as well as the product and consumer.

The main hypothesis of this study is that employing local celebrity endorsement can be as effective as traditional, well-known celebrity endorsement. It is important to establish this because many firms, especially new ventures, lack the sufficient financial capital needed for investing in typically expensive celebrity endorsement. Therefore, the previous research on general celebrity endorsement that serves as the theoretical framework is now applied to the idea of using local celebrity endorsement. This part is the authors own integration and acts as the first part of developing and supporting the hypothesis before testing it empiri-cally.

In this thesis, a local celebrity is defined as someone famous within a region, niche, cate-gory, market or culture. The value of local celebrities might be understated. In today‟s soci-ety, it can appear that everything is a race to the top. The ultimate aim is to appear on top lists, employ top achievers, associate with A-listers, appear in the Fortune 500, and be the overall „Number 1‟. It is easy to simply focus on the mass market, rather than niche mar-kets. Therefore, the value of local celebrities is easily overlooked. What should be kept in mind is that local celebrities often may experience the same type of attention from the pub-lic as a well-known celebrity, although in the limits of their particular region or context. For newly started ventures, this may be especially true as recent research by Pae, Samiee and Tai (2002) shows that localized advertising messages are especially effective when brand knowledge is low. This is because these types of new and unknown brands require creative and culturally-compatible advertising for each market (Pae, et al., 2002). Further, it was found that consumers perceive local advertisements to be more interesting, less irritating, and generally preferred them to foreign commercials. Local advertisements were even pre-ferred in terms of purchase intentions (Pae, et al., 2002). The bottom line is that firms should look beyond mass marketing and explore the values of niche markets with their re-spective local celebrities.

3.1.1 Celebrities with Benefits

The authors of this thesis propose that the benefits of using a local celebrity in marketing communications could be many. The most obvious, of course, is their more reasonable price tag compared to well-known celebrities. Intuitively, the lesser known the celebrity is to the general public, the less she or he will be able to charge for the endorsement contract. Some local celebrities might even see this as a good opportunity for wanted publicity, and the deal could be closed at an even lower price than expected. Also intuitively; local, less-known celebrities are more likely to be easier to reach out to and employ. They probably have fewer items and commitments on their agenda and not as many people and opportun-ities fighting for their attention.

Perhaps most importantly, the local celebrity can be easier to relate to. Local celebrities are more likely to be seen in their everyday life and therefore be viewed as more real. A local celebrity is someone who is seen more as an average person, someone approachable by the

masses. An important theoretical finding in this context is that local commercials (involving a local celebrity) seem to „naturally personify‟ cultural traits that local consumers under-stand and can relate to (Pae et al., 2002).

It has also been established that choosing the „right‟ celebrity is not simply about fame lev-el. Rather, the perceived fit between the product and the celebrity may be as important to consumers (The NPD Group/Celebrity Influence Study, 2006). Arguably, it will be easier to successfully fit a local brand with a local celebrity.

Finally, assumptions could be made about the negative aspects of celebrity endorsements. One of the major concerns of using celebrity endorsement is the risk for a negative image transfer to take place between the celebrity and the product. This can happen if the celebri-ty is involved in a real or alleged scandal, or if negative information is revealed about the celebrity (Andersen, 1983). Although it cannot be said with certainty, local celebrities can very well be assumed less prone to be involved in a scandal and in turn negatively affect the company. The argument is that local celebrities are not surrounded with as much media at-tention as well-known celebrities. This decreases the risk for false negative information about the celebrity to arise.

Under the following sub-headings, the benefits of using a local celebrity endorser will be discussed briefly in terms of the following concepts used throughout the thesis.

3.1.1.1 Trustworthiness

As stated in the section above, local celebrities are thought to be easier to relate to. It also seems that this may have positive effects on the effectiveness of celebrity endorsement. Erdogan (1999) contents that in order to gain communication effectiveness, the chosen endorser should be one that people can relate to and is similar to the target group. This is because consumers more easily can trust these individuals. As it seems, a local celebrity should be perceived more trustworthy than a more famous celebrity.

3.1.1.2 Expertise

Perceived expertise is pointed out as the second important condition for being a credible communicator (Hovland, 1953). However, it is hard to guess whether or not local celebri-ties can be perceived at least as expert as better known celebricelebri-ties. There might not be a distinction between local and well-known celebrities in possession of knowledge, expe-rience and skills. However, since expertise also is defined as the ability of the source to make truthful statements (Erdogan, 1999), it could be presumed that since local celebrities might be trusted more, they are also „trusted to be expert‟ if so is portrayed.

Hypothesis 1: Local celebrity endorsement can be viewed at least as credible as well-known celebrity endors-ers.

3.1.1.3 Attractiveness

The communication effectiveness of the message partly depends on the familiarity, similari-ty and likeabilisimilari-ty of the endorser (McCracken, 1989). Arguably, celebrities that are local and seemingly closer to the public may be perceived more familiar and similar. Most notable is probably the similarity characteristic. Similarity is a reoccurring factor of importance in the study of influence and persuasion. Apparently, human beings inherently rely on the people around them for how to think, feel, and act. It is also said that influence is often best when exerted horizontally rather than vertically (Cialdini, 2001). In other words, people are more likely to be influenced by an endorser who seems closer to them. However, this being said

about the first two characteristics making up attractiveness, it cannot be predicted whether local celebrities should be more likeable than better known celebrities or not.

Hypothesis 2: Local celebrity endorsers can be perceived equally attractive as well-known celebrity endorsers. 3.1.1.4 Emotional Involvement

Local celebrity endorsers are likely to be more emotionally involved than a well-known ce-lebrity endorser. Recall that emotional involvement refers to the cece-lebrity endorser‟s moti-vation to appear in the advertisement (Hunter, 2009). Even if the financial compensation for a well-known celebrity will be much higher, other factors can motivate a celebrity to take part of the endorsement. For a local celebrity, an endorsement contract may be very desirable since it may provide needed visibility and attention. A local celebrity might there-fore be more motivated to stay in good terms with the company in question, and make a true effort to live up to its expectations for the endorsement. In short, an endorsement contract could be a „bigger deal‟ for a local celebrity than a well-known celebrity, and they are more likely to make sure to keep it such.

On the other side of the coin, newly started ventures cannot provide any prestige that oth-erwise might be rubbed off on celebrities who land a major contract with one of the larger brands such as Nike, Coca Cola or L‟Oréal. Therefore, employing a well-known celebrity might outright be a bad idea. Even if they receive the sufficient financial compensation, they will unlikely show any signs of emotional involvement. If the newly started venture has yet to prove its worth, the celebrity is fairly unlikely to get involved more than neces-sary in the endorsement process.

Hypothesis 3: Local celebrities can be perceived at least as emotionally involved in the endorsement process as well-known celebrities.

3.1.1.5 Meaning Transfer

As McCracken (1989) argues, it is the cultural meaning of the celebrity that is important in the endorsement process. As already stated, consumers understand and relate more easily to local cultural traits (Pae et al., 2002). Of course, a local celebrity would personify these in a much more realistic way than a well-known superstar. Therefore, local celebrities would be more successful in transferring true meaning to the endorsed brand. In addition, local celebrities are thought to be more compatible with smaller, newly started ventures. There is a more natural „fit‟. Usually, the new ventures start out very local anyway, so there is no need to try to gain unneeded attention and employ an expensive well-known celebrity. Hypothesis 4: Local celebrities can be as capable of transferring meaning to the endorsed product as well-known celebrities.

3.2 Communication Effectiveness of Local and Well-known

Celebrity Endorsement

Below is a proposed model that extends to include not only the source models, but also the meaning transfer model as well as emotional involvement to measure the communication effectiveness of local and well-known celebrity endorsers. Ohanian‟s (1990) source credibil-ity scale is used in determining the celebrcredibil-ity characteristics for the trustworthiness- and ex-pertise-dimensions. As for attractiveness, the characteristics are drawn from McGuire‟s (1985) research. In the context of predicting the effectiveness of local versus well-known celebrity endorsement, these characteristics are more suitable than those proposed by

Oha-nian (1990). The reason for this is since the focus lies on attraction based on recognition as opposed to merely physical appeal. Also, it has been important to include the concept of meaning transfer since local celebrities are believed (by the authors) to be perceived as more compatible with the brands of smaller, newly started ventures than larger celebrities would be. Emotional involvement is also important, as local celebrity endorsers are as-sumed to show higher emotional involvement in the endorsement process than larger cele-brity endorsers might. This model should be well suited to be used in the testing of local and well-known celebrity endorsement. From this, the last hypothesis can be formed, which serves to capture the purpose of the study.

Hypothesis 5: Local celebrity endorsement can be at least as effective as well-known celebrity endorsement.

Figure 3.1: Proposed model to test communication effectiveness of local versus well-known celebrity endorsement, created by the authors