REGISTERED NURSES’ EXPERIENCES OF MEETING PATIENTS’

SPIRITUAL NEEDS IN A HOSPITAL SETTING IN PERU

Bachelor of Science in Nursing, 180 credits Bachelor’s Degree Project, 15 credits Date of Examination: August 27th 2019 Course: 51

Author: Brenda Soto Ticona Supervisor: Marie Tyrrell

ABSTRACT Background

Spirituality is within into every person even though the spiritual experience is always individual. Well-being and happiness are related to the amount of spirituality influencing one’s life. Patients spiritual distress and needs often emerge from their experience of suffering. Acknowledging patients’ spirituality needs, and possessing skills to meet such needs, are crucial to provide holistic care; unmet spiritual needs can could increase patient´s suffering. Spiritual care is included in registered nurses’ responsibility, although the focus and involvement of spiritual care, depends on their personal experiences. Aim

The aim was to examine registered nurses’ experiences of meeting patients’ spiritual needs in a hospital setting in Peru.

Method

A qualitative design was performed with semi-structured interviews. Nine registered nurses were interviewed, the collected data was analysed with a qualitative content analysis.

Findings

Three categories were found in the analysis; Recognition of professional responsibilities in

providing spiritual care, Integrating spiritual care into clinical practice and Impact of spiritual care. The findings show how holding a holistic view impacted the delivery of

spiritual care. Conclusion

It is difficult to use specific strategies to meet spiritual needs since needs are

individual. Meeting spiritual needs must always be done with respect for the patients’ ways of expressing their spirituality. Being available and listening are important elements of meeting patients’ spiritual needs. Spiritual care is recognised as an inseparable part of holistic care and the involvement of spiritual care is essential for patients healing. Keywords: Peru, Registered nurses’ experiences, Spiritual care, Spiritual needs.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ... 1

BACKGROUND ... 1

The Peruvian context ... 1

Spirituality as a concept ... 2

Spirituality in the context of health care ... 3

Study Rationale ... 5 AIM ... 5 METHOD ... 6 Design ... 6 Study Participants ... 6 Data Collection ... 7

Data Processing and Analysis ... 7

Ethical Considerations ... 8

FINDINGS ... 10

Recognition of professional responsibilities in providing spiritual care ... 10

Integrating spiritual care into clinical practice ... 11

Impact of spiritual care ... 13

DISCUSSION ... 14

Discussion of Findings ... 14

Discussion of Method ... 15

Conclusion and relevance for the clinical practice ... 17

Further Studies ... 17

REFERENCES ... 18

1 INTRODUCTION

Spirituality and health care have long been related to each other, however, health care today is poorly equipped to meet patients’ spiritual needs due to the decreased influence of spirituality in health care (Sivonen, 2017). The lack of spiritual care may lead to unrelieved spiritual distress and increased suffering among patients (Clark & Hunter, 2019). The World Health Organization [WHO] (2007) states that providing spiritual care is included in registered nurses’ professional responsibilities. Hence, the neglected of spiritual needs and inadequate performed spiritual nursing care, motivated our interest to explore the topic through this study.

The influence of spirituality in the Peruvian society, and its health care is considerable (Ministerio de Salud, 2007), with this in mind, conducting the study in Peru was motivated. In order to perform the study in Peru a Minor Field Study (MFS) was carried out, MFS is a program intendent for university students and is financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida, n.d).

BACKGROUND The Peruvian context

Peru is located in the western part of South America and has approximately 31 million inhabitants (WHO, n.d) with different ethnicities influenced from Africa, Europa, East and the native Inca (INPEDA, 2010). Peru is considered a religious country where the majority of the Peruvian population are Roman Catholics (Vaggione, Morán & Fáundes, 2017). The health care system in Peru

The United Nations Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development Goals was adopted by world leaders in 2015 and was developed to achieve a better and sustainable world for all. The agenda includes 17 goals and all countries are required to participate and take action in order to reach the goals by 2030 (United Nations [UN], n.d). Governments have an

important role in reaching the goals through applying national policy guidelines and standards. By ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being, the Peruvian government tackles issues within Goal 3; Good health and well-being (UN, 2017).

There are different types of organisations that provide health care in Peru. The Ministry of Health (MINSA) is controlled by the Peruvian government and is responsible for the healthcare sector and provides health services for 60 percent of the population (Gob, 2018). Essalud is a social health insurance for all the Peruvian population, which is

attached to the ministry of labour and employment promotion, and provides health services for 30 percent of the population, and the remaining 10 percent is provided health services from private or other sectors, such as churches and other denominations (WHO, n.d). The mission of the health care providers in Peru is to protect the dignity of the person, to promote health, and to prevent diseases. The core of the health care service is to promote an individual care at the center. Health care offered should be accessible in all parts of the country, for the entire Peruvian population. The foundation consists of respect for the natural course of life, fundamental rights, quality of care, and to contribute to the development of the society (Gob, 2018).

2 Nurse education in Peru

The Congreso de la República (2002), in accordance with the International Council of Nurses [ICN] (2012), states that registered nurses’ essential responsibilities include promotion and maintenance of health, prevention of illness and relieving of suffering. Registered nurses’ main professional responsibility is to provide nursing care to people whom are in need of care. When providing nursing care, human rights, traditions, values and spiritual beliefs of the person, family and society must always be respected and taken into consideration (ICN, 2012).

The Congreso de la República (2002) states that to obtain the title of registered nurse and work in the nursing profession in Peru, the person must have a university degree connected to the Peruvian Nursing College. Nurse education consists of a four-year theoretical

educational programme followed by one year internship. The Peruvian nurse education aims to provide the necessary knowledge and practical skills to offer comprehensive care to people, based on their physical, psychological and social needs (WHO, 2017). The nursing curriculum also includes the recognition, respect and support for people’s spiritual needs and it highlights the importance of nurses’ professional responsibility towards spiritual care (Universidad Nacional de centro del Perú, 2017).

Spiritual influences in Peru

The 28th article of Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) states that everyone has the right to manifest one’s religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, observance and traditions. Both religion and spirituality influence the Peruvian society, the religious institutions are part of the national agreement, and have the participation for the vision of the country in the future (Ministerio de Salud, 2007), and also is Peru one of the few countries in South America where the majority (54,2 percent) of the population are indigenous peoples, the spirituality for the indigenous people is significant by becoming part of the basic and having a strong connection, such as "La Pachamama" which is the mother earth (INPEDA, 2010).

Walter, Masias, Muñoz and Arpasi (2013) studied the individual influence of spirituality in 397 study participants living and working in Peru. The result of their study shows that over half of the participants were influenced by spirituality in their everyday-life and a large proportion of participants were influenced by spirituality in their working-life. The result also shows that well-being and happiness is related to the amount of spirituality

influencing one's life, the majority of the employees with high influence of spirituality expressed the sense of well-being and happiness (Walter, et al., 2013).

Spirituality as a concept

Spirituality is within every person but the spiritual experience is always individual and subjective (Baldacchino, 2006). Spirituality can be found in different aspects such as religion, values, culture, beliefs of and existential questions (McSherry & Cash, 2003). Sivonen (2017) describes spirituality as a connection to the innermost and centremost of the human being, in this context, spirituality is seen as a strength, and excellence which becomes an element for achieving life ascendance.

3

Leeuwen et al. (2006) emphasize that spirituality, as a part of the human function, is expressed in various ways, depending on the person’s experience, perception, and meaning of life. With this approach spirituality includes all individuals, even agnostics and atheists (Miner-Williams, 2006).

O’Brien, Kinloch, Groves and Jack (2019) explain the difficulties of defining the concept of spirituality by pointing out the association between spirituality and religion. WHO (1990) states that spirituality refers to those aspects of human life which have to do with experiences which exceed sensory phenomena. Salgado (2014) explains further that

spirituality is not the same as religion, although for many people, the spiritual dimension of their lives includes a religious component. According to Chan (2010) religion can be seen as part of spirituality in which humans can practice or express their spirituality within their faith. Having a faith or belief in something that is greater than oneself could refer to as having a role model within spirituality, for instance, having a faith in God (Rosengren, 2017). A belief can be described as the human’s innermost strength, which originates from spirituality, and can help humans to overcome their fears and difficulties in life (Tirrell et al., 2019).

Spirituality is mainly described in history of health care as ethics and morals which had a strong influence in the early days of the nursing profession. For instance, Florence Nightingale believed that the integration of spirituality was essential for nursing care (Sivonen, 2017). Having a spiritual belief is considered a resource of strength in registered nurses’ working life (Näsman, Nyström, & Eriksson, 2012). Daher, Chaar and Saini (2015) mean that nursing is a moral profession built on values and that registered nurses’ morality is affected by their spiritual health and belief.

Spirituality in the context of health care

According to WHO (2007) the spiritual dimension of the patient is included in providing a holistic care. Holistic care implies seeing the patient as a whole person and to provide such care involves focusing on the patient’s physical, social, mental and spiritual needs (Chan, 2010). Despite this, the spiritual dimension gets less attention compared to other

dimensions of the patient (Hodge & Horvath, 2011; Rocha, Pereira, Silva, de Medeiros, Refrande & Refrande, 2018). O’Brien et al. (2019) emphasise that acknowledging patients’ spiritual needs and possessing skills to meet such needs are crucial to provide holistic care. O’Brien et al., (2019) emphasize the importance to include spirituality in the individual care planning in order to highlight patients’ spiritual needs, therefore the healthcare providers needs to give the spiritual care depending of the patient’s individual

circumstances, wishes or belief. According to Puchalski (2013) Spirituality is part of the basis for holistic and person-centered care, which is grounded in values of compassion and service to others. Yardley, Walshe and Parr (2009) emphasize the importance of meeting spiritual needs by pointing out reports of decreased satisfaction with health care when patients’ spiritual needs were unmet.

Spiritual health

Spiritual health is defined as a person’s spiritual awareness which creates a personal development with a conscious, dynamic, universal and multidimensional morally growth (Jaberi, Momennasab, Yektatalab, Ebadi & Cheraghi, 2017). Spiritual health is essential for one’s physical and emotional well-being, and the growth of spiritual health helps

4

patients to transcend their suffering (Egnew, 2005). Braun et al. (2016) means that patients suffering can be relieved through a holistic approach that includes focus on spirituality and the relieving of spiritual distress. Suffering is a physical, psychological, spiritual or

existential experience of pain, anxiety or distress (Arman, 2017). Patients spiritual needs often emerge from their experience of suffering (Baldacchino, 2006; Chan, 2010;

Ramezani, Ahmadi, Mohammadi & Kazemnejad, 2014). Depression, sense of loneliness and loss of meaning in life can be indicators to identify a person whose spiritual health is at risk (Daher et al., 2015).

Spiritual needs mostly concern purpose and meaning, values and fulfilment in life; For example, it can be a need to express belief or values, but also a need for strength and hope (McSherry, 2006). McSherry (2006) claims also that spiritual needs are connected with the other aspects as psychological, physiological and social, and therefore, a holistic approach to health care is a prerequisite in order to understand an individual's needs. According to McClain, Rosenfeld & Breitbart (2003) it is common for patients to turn to religion for answers to their spiritual needs, but others can also find strength through their

non-religious spiritual beliefs. There is an ability to find or sustain meaning in one's life during terminal illness might help to deter end-of-life despair to a greater extent than spiritual well-being rooted in one’s religious faith (McClain, Rosenfeld & Breitbart, 2003). Palatta (2018) explains that the Person-Centered Care delivers a multidimensional perspective on the person in relation to her or his disease and overall health, and the environment around the person. Promoting Person-Centered Care can help the caregiver to provide an optimal and individual care. Chan (2012) mean that patients need to feel

acknowledged by the health care personnel in order to feel comfortable talking about their spiritual needs. Further Pedersen and Sivonen (2012) explains the importance of focusing on identifying the reason for spiritual distress in order to understand better the patient as an individual and discover how to meet their needs.

Spiritual care aims to relieve patients’ spiritual distress by identifying and meeting their spiritual needs (Braun, Kornhuber, & Lenz, 2016). Harrison, Young, Price, Butow and Solomon (2009) reviewed 94 supportive care studies which showed up to one half of the patients in the study indicate that their spiritual needs were unmet. According to Mourão et al., (2017) unmet spiritual needs can create a profound impact on the patient’s symptoms and increase their suffering.

Tirrell et al., (2019) mean that patients are capable of finding meaning in their suffering through their spiritual belief, which also creates strength to face difficulties and trials that appear related to their suffering. Further Clark and Hunter (2019) explains that finding meaning in suffering helps patients to cope better with their disease and leads to transcendence of suffering.

According to Leeuwen et al. (2006), meeting patients’ spiritual needs are included in registered nurses’ responsibility, although the focus and involvement of spirituality, depends on their personal experiences and commitment to the subject. Mamier, Taylor and Winslow (2019) studied the prevalence of spiritual care amongst registered nurses with different religious and spiritual beliefs. Their findings show that registered nurses practice in spiritual care increased, regardless of their own religious or spiritual beliefs, if they had received spiritual training.

5

According to Battey (2012), there are many reasons why registered nurses find it hard to meet patients’ spiritual needs, the most common reason is described as the absence of spiritual care in the nursing education. The lack of knowledge about spirituality among registered nurses creates barriers in interacting with the patient’s spiritual thoughts and questions (Battey, 2012). Leeuwen et al. (2006) explains further that registered nurses believe they should not attempt to approach a patient's spiritual distress if they are not able to follow it through. Selman et al., (2018); Steinhauser and Balboni (2017) argue that registered nurses’ confidence regarding meeting patients’ spiritual needs can increase by focusing on listening and spiritual valuation in nursing education. Minton et al. (2018) highlights the importance for health care personnel to acknowledge that patients’ spiritual inquiries may not always need to be answered and that silence can encourage patients to express their inner concerns, further (Selby, Seccaraccia, Huth, Kurppa, & Fitch, 2017) explains that listening should be the main focus to meet patients’ spiritual needs. By means of the health care personnels’ ability to listen and be sensitive to patients’ spiritual needs, patients can experience sense of hope which helps to transcend their suffering (Chan, 2010). Although there are unanswered questions about the content of spiritual care, meeting patients’ spiritual needs is included in registered nurses’ professional

responsibility (Battey, 2012; Chan, 2010; Leeuwen et al., 2006; O’Brien et al., 2019; WHO, 2007).

Study Rationale

The responsibility of health care personnel to address patients’ spiritual needs has been stressed, and there is a great amount of research that emphasizes the importance of spiritual care and to relieve patients’ spiritual distress. However, there is a lack of knowledge about how to meet patients’ spiritual needs.

To achieve holistic care, registered nurses are required to see patients as a whole person and meet their physical, social, mental and spiritual needs. Spiritual needs receive less attention compared to the other domains within holistic care, despite the fact that it is regarded as one of the professional responsibilities of a registered nurse. The lack of spiritual care training and knowledge about spirituality among registered nurses puts them in a position where they feel reluctant to interact with patients’ spiritual thoughts and questions. This can lead to unrelieved spiritual distress among patients which can become an obstacle to achieve health and well-being.

Enhanced understanding about how to meet patients’ spiritual needs are needed, hence, this study wishes to investigate the experiences of registered nurses in meeting spiritual needs in a hospital in Peru.

AIM

The aim was to examine registered nurses’ experiences of meeting patients’ spiritual needs in a hospital setting in Peru.

6 METHOD

Design

In order to gain an understanding of the studied phenomenon through registered nurses’ experiences, a qualitative design with semi-structured interviews was performed. With an inductive approach this qualitative design enabled an understanding based on nurses´ subjective (experiential) perspectives (Polit & Beck, 2017).

Study Participants Inclusion criteria

The selection of participants was based on criteria which corresponded to the aim of the study. Three inclusion criteria were chosen; to be a registered nurse according to the regulations in Peru, working at the hospital were the interviews were conducted, and speak Spanish.

Sample method

The participants were recruited by using a convenience sampling method, also referred to as volunteer sampling. According to Polit and Beck (2017), this sampling method is appropriate when the most convenient available participants, who correspond to the

inclusion criteria, ought to be recruited. Considering the framework of a Bachelor’s Degree Project and acknowledging the limit of time for conducting the research, a convenience sample of nine participants were considered suitable in order to gather enough variations of experiences.

Recruitment process

To get in contact with registered nurses who corresponded to the inclusion criteria, a hospital in Peru was contacted via phone and a brief information letter describing the study was sent via mail four months prior to the study performance (Appendix A). The

generation of data at the hospital was approved by the director of the hospital who signed an approval form (Appendix B). Furthermore, written and verbal information about the study were given on site to registered nurses working at the hospital before they were asked to participate in the study. The hospital is connected, and belongs to a Christian institution and is built on the values; honesty, commitment, responsibility, aid, morals, respect and faith in God.

Description of study participants

The participants in the study were nine women working as registered nurses in Peru, their working experience as registered nurses varied between five months to thirty-six years. All participants were employed at the same hospital in Peru but were working in different wards; emergency, trauma, neonatal, intensive care unit, pediatrics, gynecology and epidemiology.

7 Data Collection

The data was generated through semi-structured interviews. During semi-structured interviews the interviewer uses an interview guide as support and guidance but forms the interview through the dialogue with the participant (Polit & Beck, 2017). The interview guide was conducted based on four topics containing related questions which responded to the aim of the study (Appendix D). The interview guide was initiated with General

questions followed by Meaning of concepts to clarify a corresponding perception of

significant concepts before carrying out the interview. The following topics were

Experiences of responsibility toward spiritual care and Experiences regarding spiritual care, which were designed to answer the studies aim. Additional questions were prepared

as follow-up questions, if the participants answers needed to be clarified or if further information would be of interest for the study. To facilitate for the participants to speak freely about the topics narrative descriptions, the questions were designed with an open-ending in order to avoid short answer such as “yes” and “no” (Polit & Beck, 2017). Pilot interview

A pilot interview was conducted, also referred to as practice interview, with the purpose to verify the technical equipment and the content of the interview guide (Polit & Beck, 2017). Transcription of the pilot interview was made with the aim to recognise potential needs for changes of questions, in order to obtain in-depth information which answered to the aim of the study. The pilot interview was used in the study since the interview guide was complete without any changes made before the following interviews.

Interview sessions

The interviews were conducted at a hospital in Peru and Spanish was the language of use during the interviews, one of the authors is a native Spanish speaker and conducted the interviews. Both authors were present during the interview sessions, one conducted the interviews and one managed the technical equipment. In order to create a comfortable atmosphere for the participants, the interview sessions were carried out in a secluded part of the hospital during the participants working hours. To ensure the accuracy of the content when transcribing the interviews, an audio-recorder was used during the interviews (Polit & Beck, 2017). One participant did not feel comfortable being audio-recorded and in compliance and respect for the participants wishes the interviewer took notes instead. The participants were welcomed to decide where the interview sessions were to be conducted, according to (Danielson, 2017) this helps the participants to feel more confident, which is preferred since the quality of the interviews decreases if the participants are stressed or not comfortable (Mårtensson & Fridlund, 2017).

Data Processing and Analysis

Transcription is the transformation from a verbal interview to a written text, the aim is to create the possibility to analyse the collected data (Polit & Beck, 2017). The audio- recorded interviews were translated and transcribed, verbatim, from verbal Spanish to written English. All interviews that have been performed was transcribed and included in the data analysis, Henricsson and Billhult (2017) explains that including all interviews strengthens the credibility of the study. To simplify the understanding of the transcriptions, markings were used, (I) for the interviewer and (P) for the participant. As a bilingual

8

speaker and translator for the interviews (author Soto) it was important to be self-conscious about the risk of modifying terms as do not contain the same certain equivalent words and phrases during translating the transcriptions (Brislin, 1970). When difficulties arouse in translating certain slang expressions used by the participants, a colleague who spoke English was consulted for further clarification.

A manifest qualitative content analysis was used to analyse the data since the essence of the collected data can easier be understood by condensing the data into smaller meaning units (Polit & Beck, 2017). The manifest content is referred to what the text actually says (Granheim & Lundman, 2004). An inductive approach was used which intends to examine a certain phenomenon without bias (Polit & Beck, 2017). Pre-understandings always influences a person’s perceptions, and this awareness was kept in mind to minimize the risk of subjective interpretations of what was said during the interviews (Priebe & Landström, 2017). Therefore, the authors discussed their pre-understandings before and during the study; to strive not to influence the research process. First, the authors read through the transcripts individually, and after that summaric thoughts about the data were shared that gave an overall view of the content. This decreased the risk of imprinting values to the information and increased the credibility (Polit & Beck, 2017).

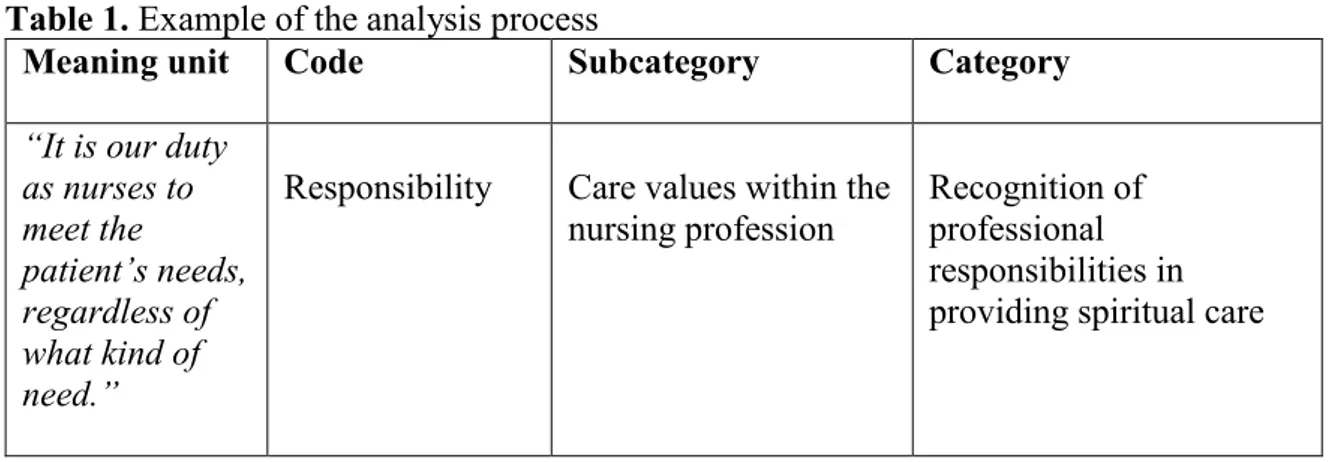

After having read the data form a whole, meaning units were generated from the texts. Meaning units consist of words, sentences or paragraphs which has a common meaning of relevance to the aim of the study (Granheim & Lundman, 2004). The next step in the content analysis was to condense the meaning units into codes, which consisted of one or a few words. Coding is the foundation of creating categories and subcategories which can be seen as clusters of meaning units with the same substance (Granheim & Lundman, 2004). Quotations were presented in the reporting of findings, which strengthens the credibility of the analysis process (Danielson, 2017). Example of meaning unit, code, subcategory and category that emerged during the content analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Example of the analysis process

Meaning unit Code Subcategory Category

“It is our duty as nurses to meet the patient’s needs, regardless of what kind of need.”

Responsibility Care values within the

nursing profession Recognition of professional responsibilities in providing spiritual care

Ethical Considerations

The World Medical Association [WMA] (2013) states in the Declaration of Helsinki that no human who is capable of giving informed consent ought to be included in a research without a voluntary consent. Freely-given informed consent was received from all the participants before the interviews (Appendix C). In accordance with Helgesson (2015), a comprehension of the meaning to participate was established through verbal and written

9

adequate information about the study, covering the study’s aim and method as well as the right to regret and discontinue the participation during the whole study, without any consequences for the participant or explanation needed. The interviews were audio-recorded with the purpose to minimize the risk to unintentionally modify the participants answers due to subjective thoughts and assumptions. The participants voluntary decided if the interview were to be recorded or not after being informed about its purpose.

All research related to human must always protect the participants’ life, health, dignity, integrity, autonomy, privacy and confidentiality (WMA, 2013). In accordance with Helgesson (2015), eventual risks for the participants were evaluated and precautions were made before and during the study in order to minimize the risks for participation. The confidentiality of the participants was an ethical consideration in focus throughout the study. To maintain confidentiality of the participants all collected data was stored out of reach from unauthorized people, only the authors were authorized, the audio-recorded interviews were erased after being transcribed as well as the transcriptions after finishing the study (Polit & Beck, 2017). Furthermore, the participants personal information was not presented in the study, nor the name or location of the hospital where the participants were recruited from to minimize the risk for recognition of the participants. The both authors had reflected and talked about the cultural differences, but the author who conducted the interview have the same culture as the participants which was not a barrier.

The aim to generate new knowledge from research ought to be evaluated and balanced with the rights and interest of the study participants, the interest of research can never be prioritised over the interest of the participants (WMA, 2013). The benefits and risks was considered in order to legitimate the study, in accordance with the Swedish Research Council (2017), the participants’ effort and time spent participating in the study was balanced with a method which answered the aim of the study.

10 FINDINGS

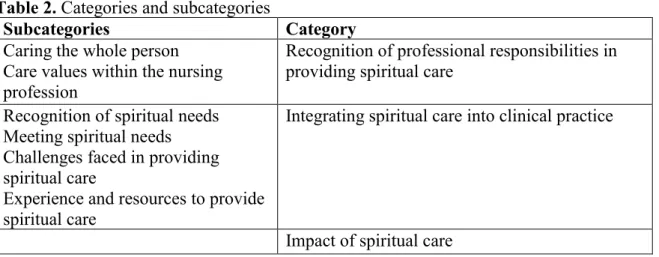

The final categories and subcategories are presented in Table 2. The findings in this study are presented under three categories and six subcategories. The categories found were

Recognition of professional responsibilities in providing spiritual care, Integrating spiritual care into clinical practice and Impact of spiritual care. The categories and

subcategories are presented under separate headings. Table 2. Categories and subcategories

Subcategories Category

Caring the whole person Care values within the nursing profession

Recognition of professional responsibilities in providing spiritual care

Recognition of spiritual needs Meeting spiritual needs Challenges faced in providing spiritual care

Experience and resources to provide spiritual care

Integrating spiritual care into clinical practice

Impact of spiritual care

Recognition of professional responsibilities in providing spiritual care Caring the whole person

The participants emphasised the importance of providing holistic care and explained their responsibility as seeing a person as a whole and meeting all needs of the patient. Holistic care was recognised by the participants as integral care, where the physical, psychological, social, emotional and spiritual parts of the patient are included and always needs to be respected and taken in consideration when caring for patients.

“I think that it [spiritual care] is included and is part of it [holistic care], because holistic care is everything, complete, where spiritual care comes in, so it cannot be

separated.”

In order to respect the patient’s integrity and right to decide how they view and express their spirituality, the participants expressed the need to be sensitive toward patients’ spirituality. If patients wanted to talk about spiritual concerns, the participants emphasised the importance to be careful and give thoughtful answers in order to gain the patient’s trust.

“Always, always with respect, respect is important, knowing that there are other beliefs and other ways of thinking about spirituality or existence. You want to establish a good

relationship and trust, that's why you have to be careful.”

Care values within the nursing profession

Relieving patients’ spiritual distress was described as the registered nurses’ main responsibility toward spiritual care. The participants perceptions of their responsibility within spiritual care was explained as praying with or for the patient, create trust, and initiate conversations, listen to the patient, calm the patient with medication if it needed, be supportive and give hope.

11

“Talk to the patient, give support, it may happen that the patient feels anxiety due to the situation and then we as nurses should try to relieve the anxiety and explain that it can

happen to anyone or so.”

The participants explained that if they noticed that a patient need spiritual…If patients’ spiritual needs appear overly advanced for the registered nurses to approach, their responsibility to involve other professions were recognized. In order to address the right skills to meet the needs the patient’s doctor or the chaplaincy of the hospital were involved.

“Well, when I see that the patient needs spiritual care, I try to plan my day to be able to talk with the patient during the day because time is needed for this and at the same

time see if it is me who can give that resource or if a contact with the chaplaincy is needed.”

Integrating spiritual care into clinical practice Recognition of spiritual needs

The first method to identify patients’ spiritual needs was to observe the patient and look for symptoms that could indicate that the patient suffered from spiritual distress. The

participants explained that they observed the patient as a whole, facial expressions, body language and the sound of their voice. If the patient was worried or concerned, felt anxious, sad or depressed could indicate that they suffered from spiritual distress. If the patient was worried or concerned, felt anxious, sad or depressed could be a symptom as indicate spiritual distress. The participants emphasised the importance of listening, be available and receptive in order to create trust and give the opportunity for the patients to talk about their spiritual concerns.

“Well, in my experience, the observation, the observation of the person, if the person looks depressed or worried then I make a conversation with the patient and also identify the

spiritual needs that the patient has. More than everything is the dialogue and observation.”

If the patient is going through a difficult experience, for example a severe disease or pain, the participants explained that looking for symptoms was not needed because the spiritual needs are obvious when the suffering is severe.

“In my own experience, what I experienced, was for example when I had patients who were in advanced pregnancy but due to clinical problems had a miscarriage, I can say that I

have seen the suffering of the couple up close.”

Meeting spiritual needs

To meet patients’ spiritual needs, the participants explained that a good relationship and communication with the patient are crucial to obtain their trust and reach the patients inner thoughts. The participants did not have any specific strategies, since every patient needs to be treated individually, but efforts were made to make the patient comfortable enough to talk about spiritual concerns through showing kindness and the availability to listen. If the registered nurses experienced that a patient had spiritual needs, they tried to make time during their working day to talk with the patient.

12

“Communication, I have no strategies but if the patient needs to talk it is important that we listen to them. There is no strategies or protocols to use, it is only your own ability to see

the whole person and address their needs.”

If there was an opportunity to pray with or for the patient the participants asked the patients if they would like to receive this kind of spiritual care, the registered nurses explained that almost everyone accepts and even though it does not relieve all the suffering, it usually calms the patients and ease their distress.

“It is difficult to alleviate the patient's distress entirely but through prayer and giving words of encouragement and support it can help to diminish.”

Challenges faced in providing spiritual care

When it comes to meeting patients’ spiritual needs, the participants expressed different obstacles which obstructed them from providing spiritual care, the patient’s relatives were described as an obstacle for many of the participants.

“Often the obstacle are the relatives, because not everyone believes or they have another belief that do not allow me or makes it difficult for me to find spiritual needs and it is hard

for me to reach.”

Some participants expressed difficulties in meeting patients’ spiritual needs, specially when the patient prefer to not talk or express it, but it can also be that the patient were or want not receptive to spiritual care, and it should be respected. It is important to know that not all the patients needs spiritual care.

“The non-believers might not think they have spiritual needs because they don’t see them.”

These situations were experienced as difficult to encounter, the registered nurses felt the responsibility to relieve the patient's spiritual distress, regardless of what kind of belief or religion they have.

“It does not matter what religion you possess it is important to fill out the emptiness that patients feel when they have spiritual needs.”

Some participants expressed that they did not feel comfortable meeting patients’ spiritual needs, they often felt reluctant to talk with patients about their spiritual matters due to uncertainty regarding the subject and the feeling of not finding the right words. Despite this, the registered nurses still thought that talking about spiritual issues with the patient is included in their responsibility. Participants who did not feel reluctant to meet patients’ spiritual needs explained that they often helped out their colleagues and they recognized it as their responsibility.

“There is nothing that obstruct me to meet the patients’ needs but many of the nurses working here find it difficult therefore it is included in my responsibility to help my

colleagues to meet spiritual needs.”

Experience and resources to provide spiritual care

The participants explained that knowledge about spirituality is fundamental to give spiritual care and most of the registered nurses had received theoretical spiritual care

13

training during their nursing education. All the participants explained that the most

important knowledge was obtained by practical experiences, either during internships or at the time they started to work as registered nurses and interacted with the patients.

“Yes, I have received knowledge from my education but after my internships I really started to understand how important the subject is for the patients, I learned the

techniques, wear to sit near the patient and how to talk to the patient.”

All the participants emphasised the importance of their own spiritual belief, it was commonly explained as the main resource to provide spiritual care. The participants explained that their own spiritual belief gave them strength and helped them to talk about difficult and sensitive matters with patients.

“I learned about spiritual care but my own spiritual belief has been my best resource to meet spiritual needs.”

Impact of spiritual care

The participants described that they could see patients recovering faster if their spiritual needs were met, spiritual care calms the patient and relieves their distress and anxiety. The participants also experienced that patients received strength and hope from spiritual care which could be used as resources for patients to overcome their disease and to achieve well-being.

“A good spiritual well-being affects how the patient is feeling in general, all parts, if the person feels good psychological and are able to get spiritual care, the patient will get

better faster.”

Many patients also showed their gratitude after received spiritual care, the registered nurses often felt appreciated afterwards and they saw that spiritual care made difference and helped the patient.

“From my experiences as a nurse can I see and notice the spiritual care that are given to the patients, it is a great help for them, because in the end when they go home they use to

say thanks a lot señorita I feel better. So in that way I have seen that it helps, a lot the spiritual care.”

The participants described that they felt good and satisfied on a professional level when they succeeded to meet patients’ spiritual needs. Talking with patients about their spiritual matters often established a good relationship built on trust and an opportunity to

understand the patients better, some participants explained further that it also strengthens their own spiritual belief or that they felt the need to strengthen it outside their work, in order to give spiritual care.

“It was mostly from my practical experience that I started to realize that I need to recognize my own spiritual belief and strengthen it […], and as a result I received better relationships with my patients, because I could understand them better.”

14 DISCUSSION

Discussion of Findings

The main findings in this study show how holding a holistic view impacted the delivery of spiritual care. Spiritual care is seen as a domain within holistic care and not an individual entity. This influences how the participants worked in meeting patients’ spiritual needs and providing spiritual care.

The findings show that the spiritual dimension of holistic care is viewed as important as other dimensions of care, and that the participants view the patient’s spiritual needs as their responsibility to encounter. This is in line with O’Brien et al. (2019); Chan (2012) who states that spiritual needs ought to be seen and treated as important as other needs of the patient. On the other hand, the findings show that patients’ spiritual needs could be

overlooked due to time limitations and other needs are in these cases prioritized. Research show that spiritual needs often are neglected by health care personnel (Rocha et al., 2018), not only due to lack of time but also as a result of lack of knowledge regarding spiritual care (Battey, 2012). All the participants in this study did receive spiritual care training during their nursing education and other research show that registered nurses are more likely to perform spiritual care if they received training in it (Mamier et al., 2019). Yet the participants could feel reluctant to interact with patients’ spiritual concerns due to the uncertainty of being able to give the right answers or find the right words. Research show that reluctance of meeting patients’ spiritual needs is common (Leeuwen et al., 2006), on the other hand, O’Brien (2019) argue that registered nurses should feel confident meeting spiritual needs, considering that answers are not always needed in response to spiritual concerns. Listening is often enough to ease patients spiritual distress (Selby et al., 2017), and silence encourage patients to reflect upon their inner concerns and to find ways to express them (Minton et al., 2018). Thereby, being available and listening can be seen as important elements of identifying and meeting patients’ spiritual needs which is confirmed by the participants in this study.

The participants described that they identified spiritual needs by observing the patient and looking for signs which indicate that the patient suffers from spiritual distress. This way of working in identifying spiritual needs is in line with Daher et al. (2015) who states that symptoms of spiritual distress indicate that a person’s spiritual health is at risk, and that these symptoms ought to be recognised in order to identify spiritual needs. Other research show that these symptoms often emerge from the experience of suffering (Baldacchino, 2006; Chan, 2010; Ramezani et al., 2014), further the findings in this study show that spiritual needs can be identified out of patients’ suffering by seeing beyond the obvious. This leads to the reflection that the participants may obtain a holistic approach toward patients’ suffering which in line with Braun et al. (2016) helps to recognise and relieve patients spiritual distress.

The findings show that praying, with or for the patient, is offered as spiritual care if the patient show symptoms of spiritual distress. This is in line with Minton, Isaacson and Banik (2016) who argue that nurses with the competence to pray should take advantage of it in order to provide broader spiritual care. The participants in this study referred to the chaplaincy when the patient needed more skilled spiritual care, this is in accordance with Fitch and Bartlett (2019) who further emphasise that registered nurses, who does not possess the ability to pray or meet patients’ spiritual needs, should be competent to

15

recognise symptoms of spiritual distress in order to involve another profession with the right competence. This could for example be the chaplaincy of the hospital, but it is of great importance not to generalise beliefs and spiritual needs, what kind of help and from who must be decided of the patient (Minton et al., 2016). This in line with the participants who described how they always respected the patients’ ways of expressing their beliefs and spiritual needs.

The participants emphasised that patients spiritual distress can ease by prayers and even though it may not relieve distress altogether, it can leave the patient with hope (Fitch & Bartlett, 2019). On the other hand, research show that patients can experience hope by means of the health care personnel’s ability to listen and be sensitive to patients’ spiritual needs (Chan, 2010). Research show that unmet spiritual needs can increase patients suffering and that hope helps to transcend suffering (Chan, 2010; Mourão et al., 2017), which is confirmed by the participants in this study who emphasised that spiritual care helps the patients healing. This leads to the reflection that the involvement of spiritual care is essential for patients healing, as in line with Egnew (2005) who states that healing is a sense of personal wholeness that involves a person’s spiritual dimension.

The findings show that it is difficult to use specific strategies to meet spiritual needs since needs always are individual and ought to be encountered with respect for the patients’ autonomy. This way of meeting spiritual needs is in line with O’Brien et al. (2019); Pedersen and Sivonen (2012) who argue that spirituality should be included in the individual care planning, and the focus should be on finding the reason for developing spiritual distress, in order to better understand the patient and discover how to meet their needs.

The participants in this study may be more aware of the spiritual dimension of care than usual since it is an exceptional situation as the participants worked in a religious setting, this is confirmed by Leeuwen et al. (2006) who argue that the focus and commitment to spiritual care depends on personal experiences of spirituality. Further the findings show that personal spiritual beliefs are used by the participants as a main resource to meet patients’ spiritual needs, which is in line with Tirrell et al. (2019) who explains that

spiritual beliefs can be a resource of strength for registered nurses in their working life. On the other hand, research show that there is a risk of misinterpreting the patients’ spiritual needs by only recognising the patients’ spiritual dimension through one’s own belief (Sivonen, 2017). This leads to the consideration that the participants may base their

knowledge and skills out of their own belief, which could be a barrier in order to recognise spiritual needs of patients with other beliefs.

Discussion of Method

The study was carried out as an empirical study due to lack of previous published research in the field. A qualitative method with interviews was considered the most appropriate method to use, since it enables the opportunity to understand experiences from subjective and narrative perspectives (Polit & Beck, 2017). In accordance to Granheim and Lundman (2004) the credibility of the study increased by choosing the most appropriate method and collect enough data necessary to answer the aim of the study. In order to study the

phenomenon empirically and unconditionally an inductive approach for the study was chosen (Henricson, 2017). However, the claim that research can be inductive has received

16

criticism since it is not possible to be completely unconditional due to previous knowledge that creates a pre-understanding of the studied phenomenon (Henricson, 2017).

A convenience sample method was used to recruit the most readily available persons willingly to participate. The disadvantage of this sampling method is that those who are available may not be able to provide the most information-rich source for answering the aim of the study (Polit & Beck, 2017). On the other hand, sampling by convenience is time saving and considering the limitation of time for the study’s execution it was the most appropriate method to use (Polit & Beck, 2017). Few criteria were used to establish a wide variety of experiences (Polit & Beck, 2017), the participants worked in a wide range of wards in the hospital. The variations in the participants experiences added to the transferability of the results of this study (Granheim & Lundman, 2004). On the other hand, all participants were recruited from the same hospital, the workplace’s values and guidelines may have affected the participants’ descriptions of their experiences, and the participants own belief may also be affected. The authors had reflected about it, and both emerged that it is positive to get supported from the hospital leaders by getting lectures and knowledge but in the other hand the workplace´s values and guidelines should not affect the own´s spirituality.

Both authors participated in each interview, a disadvantage is that it can be disturbing or incommode to the participant (Danielson, 2017), but it helped to obtain relevant

information from the interviews and to minimize the risk of forgetting important words and the meaning of what was said (Danielson, 2017). Limits of audio recordings may be that the participant becomes nervous or causes the participant to become uncertain about their opinion and not dare to speak freely (Polit & Beck, 2017).

The findings in this study reflects the individual nurses’ experiences, and due to the exceptional situation conducted this study in Peru, where the religion are connected

strongly with the culture and that the participants worked in a religious hospital setting, the transferability of the study decreased since the participants in the study had knowledge and support of spirituality. On the other hand, the findings can be transferred to registered nurses in similar contexts where the registered nurses work from the same values as the participants in this study (Polit & Beck, 2017). The authors comes from a rather secular country with no experience of Christian or religions hospitals, and it has discussed and reflected the own view of spirituality, religion in health care between each other, it helped to not let the authors preconceived perceptions affect the interviews nor the analysis. The authors had also discussed continuously their perceptions of the subject, because of, the context of this study differed from the health care context in Sweden, where the religion is not prominent in the same way.

The ethical standpoints and aspects that were made in this study were followed by being aware of protecting the participants’ identity, integrity and autonomy above all. The method was designed to answer the aim of the study which compensated for the

participants’ effort and time that was given during. The eventual risks for participating in the study were evaluated and the risk of intruding their integrity was considered due to interview questions regarding their personal spiritual belief. Precautions were made by formulating the questions regarding the subject with a sensitive approach and informing the participants that all questions are voluntarily to answer. All participants were open

17

about their belief and practices which provided in-depth information about their experiences.

Conclusion and relevance for the clinical practice

The aim of the study was to examine registered nurses’ experiences of meeting patients’ spiritual needs in a hospital setting. The findings showed that it was difficult for these study participants to use specific strategies to meet spiritual needs since needs always are individual. Hence, how patients wish to receive spiritual care must always be respected. The participants mainly used their own belief as a resource to meet spiritual needs. There was a risk of misinterpreting patients’ spiritual needs by only recognising spirituality through one’s own belief. Meeting patients’ spiritual needs should always be done with respect for the patients’ ways of expressing their spirituality. Being available and listening were important elements of identifying and meeting patients’ spiritual needs, as well as observing the patient and looking for symptoms of spiritual distress. These symptoms often emerged from the experience of suffering. A holistic approach toward patients’ suffering helped to recognise and relieve patients spiritual distress. Spiritual care was recognised as an inseparable part of holistic care and the involvement of spiritual care is essential for patients healing. To summarize, the study has provided understanding of the importance of meeting patients´ spiritual needs and provide spiritual care in various hospital settings and countries, from a person-centred perspective.

Further Studies

This study has provided understanding about registered nurses’ experiences of meeting patients’ spiritual needs in a Peruvian context. Considering that it is worldwide a relatively unexplored research area, further research is needed. To enhance the knowledge about challenges and nursing skills in meeting patients’ spiritual needs, further research is needed in various non-religious hospital settings.

18 REFERENCES

Arman, M. (2017). Lidande. I L. Wiklund Gustin & I. Bergbom (Eds.), Vårdvetenskapliga

begrepp i teori och praktik (pp. 213-223). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Baldacchino, D. R. (2016). Nursing competencies for spiritual care. Journal of Clinical

Nursing 15, 885–896.doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01643.x

Battey, B. W. (2012). Perspectives of Spiritual Care for Nurse Managers. Journal of

Nursing Management 20(8), 1012–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01360.x

Benkel, I., Molander, U., & Wijk, H. (2016). Palliativ vård: ur ett tvärprofessionellt

perspektiv. Stockholm: Liber.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-Translation for Cultural Research. Journal of

Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

Billhult, A. (2017). Bortfallsanalys och beskrivande statistik. In M. Henricson (Ed.),

Vetenskaplig Teori och metod: Från idé till examination inom omvårdnad (2nd ed., pp.

265-273). Lund: Studentlitteratur

Braun, B., Kornhuber, J., & Lenz, B. (2016). Gaming and Religion: The Impact of Spirituality and Denomination. Journal of Religion & Health, 55(4), 1464–1471. doi:10.1007/s10943-015-0152-0

Chan, M. F. (2010). Factors Affecting Nursing Staff in Practising Spiritual Care. Journal

of Clinical Nursing, 19(15–16), 2128–2136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02690.x. Clark, C. C., & Hunter, J. (2019). Spirituality, Spiritual Well-Being, and Spiritual Coping in Advanced Heart Failure: Review of the Literature. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 37(1), 56–73. doi: 10.1177/0898010118761401

Congreso de la Republica. (2002). Ley del Trabajado de la Enfermera(o). Retrieved from http://www.essalud.gob.pe/downloads/c_enfermeras/ley_de_trabajo_del_enfermero.p df

Daher, M., Chaar, B., & Saini, B. (2015). Impact of patients' religious and spiritual beliefs in pharmacy: From the perspective of the pharmacist. Research in Social & Administrative

Pharmacy, 11(1), 31-41. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.05.004

Danielson, E. (2017). Kvalitativ forskningsintervju. In. M. Henricson (Ed.), Vetenskaplig

teori och metod: Från idé till examination inom omvårdnad (2nd ed., pp. 143-153). Lund:

Studentlitteratur.

Egnew, T. R. (2005). The meaning of healing: transcending suffering. Annals of family medicine, 3(3), 255–262. doi:10.1370/afm.313

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of

19

Fitch, M. I., & Bartlett, R. (2019). Patient Perspectives about Spirituality and Spiritual Care. Asia-Pacific journal of oncology nursing, 6(2), 111–121. doi:

10.4103/apjon.apjon_62_18

Gob.pe. (2018). Ministerio de Salud. Retrieved 29 November, 2018, from https://www.gob.pe/739-ministerio-de-salud-que-hacemos/

Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B., (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing

research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education

Today, 24(2), 105-112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

Harrison, J. D., Young, J. M., Price, M. A., Butow, P. N., & Solomon, M. J. (2009). What Are the Unmet Supportive Care Needs of People with Cancer? A Systematic Review.

Supportive Care in Cancer 17(8), 1117–1128.doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0615-5.

Helgesson, G. (2015). Forskningsetik. Lund: Studentlitteratur

Henricson, M. (2017). Diskussion. In M. Henricson (Ed.), Vetenskaplig Teori och metod:

Från idé till examination inom omvårdnad (2nd ed., pp. 411-420). Lund: Studentlitteratur

Henricson M., & Billhult. A. (2017). Kvalitativ Metod. In. M. Henricson (Ed.),

Vetenskaplig teori och metod: Från idé till examination inom omvårdnad (2nd ed., pp.

111-117). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Hodge, D. R., & Horvath, V. E. (2011). Spiritual Needs in Health Care Settings: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of Clients’ Perspectives. Social Work, 56(4), 306–316. Retrieved from

https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=5&sid=60971b36-dfd0-4705-8524-512550db877e%40sdc-v-sessmgr02

Instituto Nacional de Desarollo de Pueblos Andinos, Amazónicos y Afroperuano. (2010). Aportes para un enfoque intercultural. Retrieved from

http://centroderecursos.cultura.pe/sites/default/files/rb/pdf/Aportes%20para%20un%20enf oque%20interculral.pdf

International Council of Nurses. (2012). The ICN Of Ethics for Nurses. Retrieved 19 November, 2018, from

https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/2012_ICN_Codeofethicsfornurses_%20eng.pdf

Jaberi, A., Momennasab, M., Yektatalab, S., Ebadi, A., & Cheraghi, M. A. (2017). Spiritual Health: A Concept Analysis. Journal of Religion and Health, 1-24. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0379-z

Jafari, M., Ebad, T. S., Rezaei, M., & Ashtarian, H. (2017). Association between Spiritual Health and Depression in Students. Health, Spirituality & Medical Ethics Journal, 4(2), 12-16. Retrieved from

https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=123620510&site=ehos t-live

20

Lecaros, V. (2015). Los cátolicos y la Iglesia en el Perú. Un enfoque desde la antropologia de la religión. Retrieved from

http://132.248.9.34/hevila/Culturayreligion/2015/vol9/no1/2.pdf

Leeuwen, R. V., Tiesinga, L. J., Post, D., & Jochemsen, H. (2006) Spiritual Care:

Implications for Nurses’ Professional Responsibility. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(7), 875-884. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01615.x

Mamier, I., Taylor, E. J., & Winslow, B. W. (2019). Nurse Spiritual Care: Prevalence and Correlates. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 41(4), 537–554.

doi:10.1177/0193945918776328

McClain, C. S., Rosenfeld, B., & Breitbart, W. (2003) Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet 361(9369), 1603-1607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13310-7

McSherry, W., & Cash, K. (2003). The language of spirituality: an emerging taxonomy.

International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41, 151-161. doi:10.1026/S0020-

7489(03)0014-7

Miner-Williams, D. (2006). Putting a puzzle together: making spirituality meaningful for nursing an evolving theoretical framework. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 811-821. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01351.x

Ministerio de Salud. (2007). Plan nacional concertado de salud: Situación de salud y sus

principales problemas, capítulo 2 (deposito legal No. 2007-0800). Retrieved 1 December,

2018, from http://bvs.minsa.gob.pe/local/MINSA/000_PNCS.pdf

Minton, M. E., Isaacson, M., & Banik, D. (2016). Prayer and the Registered Nurse (PRN): nurses’ reports of ease and dis-ease with patient-initiated prayer request. Journal of

Advanced Nursing (Wiley-Blackwell), 72(9), 2185–2195. doi: 10.1111/jan.12990

Minton, M., Isaacson, M., Varilek, B., Stadick, J., & O'Connell-Persaud, S. (2018). A willingness to go there: Nurses and spiritual care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(1–2), 173–181. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13867

Mourão, P. C., Gomes, T. E., Cordeiro, T. M. de F., Tenório de Almeida, C. A., Andrade, S. M., & Perrelli, V. M. (2017). Impaired religiosity and spiritual distress in people living with HIV/AIDS. Revista Gaucha de Enfermagem, 38(2), 1-7. doi:

10.1590/1983-1447.2017.02.67712

Mårtensson, J., & Fridlund, B. (2017). Vetenskaplig kvalitet i examensarbetet. In M. Henricson (Ed.), Vetenskaplig Teori och metod: Från idé till examination inom omvårdnad (2nd ed., pp. 421-438). Lund: Studentlitteratur

Näsman, Y., Nyström, L., & Eriksson, K. (2012). From Values to Virtue: The Basis for Quality of Care. International Journal for Human Caring, 16(2), 50–56.

doi.org/10.1177/0969733017695655

O’Brien, M. R., Kinloch, K., Groves, K. E., & Jack, B. A. (2019). Meeting Patients’ Spiritual Needs during End-of-Life Care: A Qualitative Study of Nurses’ and Healthcare

21

Professionals’ Perceptions of Spiritual Care Training. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(1– 2), 182-189. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14648

Palatta, A. (2018). Person-Centered Care: The “GPS” to Overall Health. Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry (15488578), 39(6), 412. Retrieved from

https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=130402631&site=ehos t-live

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2017). Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence

for Nursing Practice (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Priebe, G., & Landström, C. (2017). Den vetenskapliga kunskapens möjligheter och begränsningar - grundläggande vetenskapsteori. In M. Henricson (Ed.), Vetenskaplig teori

och metod: Från idé till examination inom omvårdnad (2nd ed., pp. 25-42). Lund:

Studentlitteratur

Puchalski, C. M. (2013). Integrating spirituality into patient care: an essential element of person-centered care. Pol Arch Med Wewn, 123(9), 491-497. Retrieved from

http://pamw.pl/sites/default/files/PAMW_2013-09_Puchalski.pdf

Ramezani, M., Ahmadi, F., Mohammadi, E., & Kazemnejad, A. (2014). Spiritual care in nursing: a concept analysis. International Nursing Review 61(2), 211-9. doi:

10.1111/inr.12099

Rosengren, A. L. (2017). Tro – en kraftkälla i vårdandet. I L. Wiklund Gustin & I. Bergbom (Eds.), Vårdvetenskapliga begrepp i teori och praktik (2nd ed., pp. 309-314).

Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Rocha Pereira, R. C., Pereira Ramos, E., Silva, R. M., de Medeiros, A. Y., Refrande, S. M., & Refrande, N. A. (2018). Spiritual needs experienced by the patient´s family caregivers under Oncology palliative care. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 2635-2642. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0873

Rudolfsson, G., Berggren, I., & Barbosa, A. (2014). Experiences of Spirituality and Spiritual Values in the Context of Nursing – An Integrative Review. The Open Nursing

Journal, 8(1), 64-70. doi: 10.2174/1874434601408010064

Salgado, A. (2013). Revisión de estudios empíricos sobre el impacto de la religión, religiosidad y espiritualidad como factores protectores. Propósitos y Representaciones,

2(1), 121-159. doi:10.20511/pyr2014.v2n1.55

Sandvik, B. M., & McCormack, B. (2018). Being person-centred in qualitative interviews: reflections on a process. International Practice Development Journal, 8(2), 1–8.

doi:10.19043/ipdj.82.008

Selby, D., Seccaraccia, D., Huth, J., Kurppa, K., & Fitch, M. (2017). Patient versus health care provider perspectives on spirituality and spiritual care: The potential to miss the moment. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 6(2), 143–152. doi: 10.21037/apm.2016.12.03

22

Selman, L. E., Brighton, L. J., Sinclair, S., Karvinen, I., Egan, R., Speck, P., & Hope, J. (2018). Patients’ and caregivers’ needs, experiences, preferences and research priorities in spiritual care: A focus group study across nine countries. Palliative Medicine, 32(1), 216– 230. doi:10.1177/0269216317734954

Sida. (n.d). Sidas stipendier och praktikprogram. Retrieved 28 April, 2019, from https://www.sida.se/Svenska/engagera-dig/sidas-stipendier-och-praktikprogram/

Sivonen, K. (2017). Ande. I L. Wiklund Gustin & I. Bergbom (Eds.), Vårdvetenskapliga

begrepp i teori och praktik (2nd ed., pp. 139-152). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Steinhauser, K. E., & Balboni, T. A. (2017). State of the Science of Spirituality and Palliative Care Research: Research Landscape and Future Directions. Journal of Pain &

Symptom Management, 54(3), 426–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.02.020

Swedish Research Council. (2017).God Forskningssed (VR1708) ISBN-No: 978-91-7307- 352-3

Tirrell, J. M., Geldhof, J. G., King, E. P., Dowling, E. M., Sim, A. T., Williams, K., Iraheta, G., Lerner, V. J., & Lener M. R. (2019). Measuring spirituality, hope and thriving among Salvadoran Youth: Initial Findings from the compassion international study of positive youth development. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48(2), 241–268. doi:

10.1007/s10566-018-9454-1

United Nations. (2017). Peru: Taking Action for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Peru_Government.pdf

United Nations. (n.d). About the Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved 15 April, 2019, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ United Nations. (1948). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved 19 April, 2019, from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf United Nations. (2008). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of indigenous People. Retrieved 15 April, 2019, from

https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Universidad Nacional de centro del Peru. (2017). Diseño Curricular Carrera Professional de Enfermeria. Retrieved from

http://www.uncp.edu.pe/sites/uncp.edu/files/pregrado/enfermeria/_pdf/diseno-enfermeria.pdf

Vaggione, J. M., & Morán, C. T. (2017). Themes in the Debates on the Regulation of Religion in Latin America. In J. M. Vaggione & C. T. Morán (Eds.), Laicidad and

Religious Diversity in Latin America (pp. 1-20). Springer International Publishing

23

Vincensi, B. B. (2019) Interconnections: Spirituality, Spiritual Care, and Patient-Centered Care. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 6(2), 104–110. doi:

10.4103/apjon.apjon_48_18

Walter, A., Masias, M., Muñoz, E., & Arpasi, M. (2013). Espiritual en el ambiente laboral y su relación con la felicidad del trabajo: Revista de investigación, (4), 9-33. Retrieved from

http://www.ucsp.edu.pe/images/direccion_de_investigacion/PDF/revista2013/Espiritualida d-y-felicidad-en-el-trabajador.pdf

World Health Organization. (1990). Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/39524/WHO_TRS_804.pdf?sequence=1& isAllowed=y

World Health Organization. (2007). People-Centred Health Care: A policy framework. Retrieved from

http://www.wpro.who.int/health_services/people_at_the_centre_of_care/documents/ENG-PCIPolicyFramework.pdf

World health organisation. (n.d). Peru. Retrieved 1 December, 2018, from http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/countries/per/en/

Yardley, S. J., Walshe, C. E., & Parr, A. (2009). Improving Training in Spiritual Care: A Qualitative Study Exploring Patient Perceptions of Professional Educational Requirements.

24

APPENDIX A

Stockholm, Sweden 2018

Dear xxx,

We are two nursing students from Sophiahemmet University in Stockholm, Sweden. We are writing you this letter as a request to perform a research for our Bachelor’s thesis at the xxx hospital.

The research area for the study is registered nurses’ experiences of meeting patients spiritual needs. The concept of spirituality has been carefully studied from a theoretical perspective, but spirituality is rarely observed in today's health care. We paid attention to the lack of focus on spiritual care during our nursing internships, even though providing spiritual care is included in registered nurses’ responsibilities. Due to the lack of focus on spiritual care, the objective with our research is to expand knowledge and describe strategies for registered nurses to encounter patient’s spiritual needs.

The data for the study will be collected through interviews, the plan is to perform six to eight individual interviews with registered nurses. All data will be treated and stored confidentially.

Preliminary interview questions:

• Is spiritual care training included in the nursing curriculum? What are your experiences of learning about spiritual care?

• What are your practical experiences as a nurse of identifying a person’s spiritual needs in a hospital setting?

• How do you feel, meeting patients’ spiritual needs? The research will be conducted in the end of Mars, 2019.

Best regards,

25 APPENDIX B Xxx, Peru 2019 Elsa Helg, +46761669226 elsa.helg@stud.shh.se Brenda Soto Ticona, +46700174038

brenda.sototicona@stud.shh.se Supervisor, Marie Tyrell marie.tyrell@shh.se

I hereby approve that Elsa Helg and Brenda Soto Ticona are allowed to perform their interviews for their Bachelor’s thesis at the xxx hospital during April, 2019.

____________________________ Place and Date

____________________________ Signature

___________________________ Name