Hälsa och samhälle

PREVENTION OF HIV

A field study of Tanzanian nurses’

culturally-adapted prevention work against HIV

GERDA TURESSON

Degree project in nursing Malmö Högskola

51-60 p Hälsa och samhälle

Nursing programme 205 06 Malmö

PREVENTION OF HIV

A field study of Tanzanian nurses’

culturally-adapted prevention work against HIV

GERDA TURESSON

Turesson, G. Prevention of HIV. A field study on the nurses’ culturally adapted HIV-prevention work in Tanzania. Degree project in nursing, 10 credit points. Nursing Programme, Malmö University: Health and Society, Department of Nurs-ing, 2006.

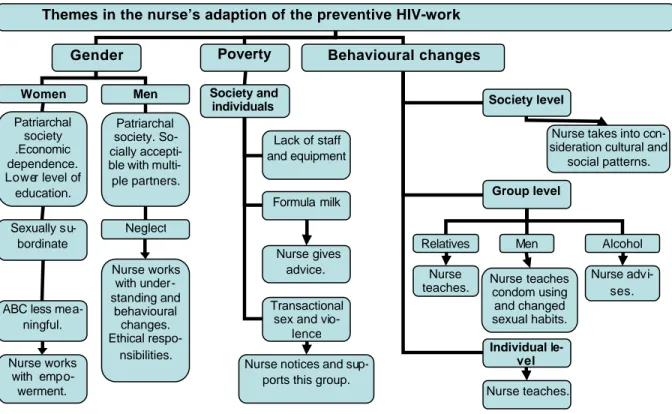

HIV is one of the gravest health problems facing the world today and Tanzania is a country deeply afflicted by the HIV epidemic. The object of this study is to in-vestigate the nurses' HIV-preventive work in the Kagera Region in Tanzania. Leininger's theory on the influence of culture on nurses’ caring work has been used as the theoretical frame of reference. The study is qualitative and the method used is ethonursing. The data has been gathered mainly through participant obser-vation and interviewing. The result reveals that the nurse has chiefly three work tasks related to HIV- prevention: health education, HIV testing and preventing the spread from mother to child. The nurse adapts her mode of work in part according to the cultural and social dimensions in which she works. Three themes showing the interaction of culture within preventative work emerge in the analysis of the result: gender, poverty and behavioural changes.

Keywords: culture, ethnonursing, HIV, Leininger, nurse, prevention, qualitative,

Tanzania.

PREVENTION AV HIV

En fältstudie om sjuksköterskans

kulturanpassa-de preventionsarbete mot HIV i Tanzania

GERDA TURESSON

Turesson, G. Prevention av HIV. En fältstudie om sjuksköterskans kulturanpassa-de preventionsarbete av HIV i Tanzania. Examensarbete i omvårdnad, 10 poäng. Malmö hö gskola: Hälsa och Samhälle, Utbildningsområde omvårdnad, 2006. HIV är ett av de största hälsoproblem som världen som står inför idag. Tanzania är ett land som drabbats hårt av HIV-epidemin. Syftet med denna studie är att un-dersöka sjuksköterskans preventiva HIV-arbete i Kageraregionen i Tanzania. Le i-ningers teori om kulturens påverkan av sjuksköterskans omvårdnadsarbete har an-vänts som teoretisk referensram. Studien är kvalitativ och använder ethnonursing som metod. Datainsamlingen har i huvudsak bestått av deltagande observation och intervjuer. Resultatet visar att sjuksköterskan i huvudsak har tre arbetsuppgif-ter avseende preventionsarbete mot HIV: hälsoupplysning, HIV-testning och att förhindra smittspridning från mor till barn. Sjuksköterskan anpassar delvis sitt ar-bete efter de kulturella och sociala dimensioner som existerar i den kontext hon arbetar i. Tre teman för kulturens inverkan på preventionsarbetet framträder vid analysen av resultatet: genus, fattigdom och beteendeförändringar.

Nyckelord: ethnonursing, HIV, kultur, kvalitativ, Leininger, prevention,

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION 5 BACKGROUND 5 Country background 5 Economy 6 Health care 6 HIV 6Social context of HIV/AIDS in Tanzania 7

The economic impact of HIV/AIDS 7

Prevention 8 Kagera region 8 Ndolage Hospital 9 PURPOSE 9 Limitations 10 Definition 10 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 10 METHOD 11 Selection 12 Gathering data 12 Participant observation 13 Interviews 13 Data analysis 14 Ethical aspects 15 RESULTS 15 Health education 16 Technological factors 16

Religious and philosophical factors 17

Kinship and social factors 17

Cultural values and lifeways 18

Political and legal factors 19

Economic factors 19

Educational factors 20

HIV-testing 20

Technological factors 21

Religious and philosophical factors 21

Kinship and social factors 21

Cultural values and lifeways 21

Political and legal factors 21

Economic factors 22

Educational factors 22

Mother-to-child 22

Technological factors 22

Kinship and social factors 23

Cultural values and lifeways 23

Political and legal factors 24

Education factors 24 DISCUSSION 25 Discussion of method 25 Choice of method 25 Selection 25 Data gathering 26 Ethical considerations 27 Trustworthiness 28

Discussion of the result 29

Gender 30 Poverty 31 Behavioural changes 32 Conclusion 34 Implications 35 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 35 REFERENCES 36 APPENDIX 40

INTRODUCTION

HIV and AIDS constitute a huge problem for the world today. Of all human be-ings who live with HIV, 60 per cent are to be found in sub-Saharan Africa, this despite the fact that they represent a mere ten percent of the world's population. UNAIDS has calculated that 3,2 million people have been infected and that 2,4 million died through AIDS during 2005 (UNAIDS, 2005). There is at present no cure for HIV which means that preventive work is extremely important.

Nurses can play a vital part in the work to prevent more people from being in-fected by HIV. As a fully qualified nurse I will be able to work in countries where HIV is prevalent. In order to perform this work meaningfully, it is important that I gain knowledge of, and insight in, the cultural and social contexts to which a nurse must adapt her work.

Even if one, as a nurse, chooses not to travel and work abroad, it is none the less important to have a cultural perspective even when working in one's own country. Today, we live in a mixed society, continuously interacting with people from dif-ferent cultures. The Swedish Health and Welfare Agency’s (Socialstyrelsen) offi-cial instructions for the nursing profession state that nurses are required to work preventively in order to promote health and fight sickness (Socialstyrelsen, 2005). This field study examines the nurse's preventive work against HIV in Tanzania, a country situated in sub-Saharan Africa and gravely affected by the HIV epidemic. I spent two months in the late summer of 2005 in a country hospital in Ndolage in order to gain understanding of the work being done there. The study could be real-ised thanks to a scholarship from the Sida, a Minor Field Study Scholarship, which is awarded to students who are working on bachelor or masters essays in developing countries. The study is therefore both an examination work and an MFS-report and will also be sent to Tanzania on completion. Appendix 1 contains a list of abbreviations to make it easier to understand the text.

BACKGROUND

It is important in a qualitative study to highlight the context of the phe nomenon that is being studied. This chapter paints therefore a picture of Tanzania as a coun-try and illustrates the existing health standards. It describes the situation concern-ing HIV and deals with possible explanations for it beconcern-ing so widely spread and also includes basic preventive measures.

Country background

Tanzania is situated just south of the equator in East Africa (appendix 1). In 1964 Tanzania became independent from the former colonial power Great Britain. The leader of the liberation movement Julius Nyerere became the first president and remained in power for 22 years in the one-party state of Tanzania. His goal, as expressed in the Arusha declaration of 1967, was to create a socialist state based on African terms. His vision was that the entire society should function as a fa

m-ily and that development would be brought forward through national mobilisation, state owned villages and collective farming. But the war against Idi Amin’s Uganda 1978-1979 had a severe effect on the Tanzanian economy. This, in com-bination with external debts, destabilised the economy and in the middle of the 1980s Nyerere’s socialistic system broke down. In 1995, the first election involv-ing several parties was held (ibid). Nyerere’s successor as president, Benjmin Mkapa ruled for ten years and resigned after the elections this autumn. The winner of the elections and the coming president is Jakaya Kikwete, who also represents the Revolutionary party (CCM) that still completely dominates the political life of Tanzania (DN, 19/12 2005).

The country is home to over 120 different tribal groups, the majority of which are

of Bantu origin. There are also small, but economically significant, populations of Asian and Arabic origin. Swahili and English are the official languages which connect the 35 million inhabitants, even though many tribal languages are spoken. Christians represent about 45 % of the population and Muslims slightly more than one third. The remainder are adherents of traditional, indigenous religions. Two thirds of the Christians are Catholics and the rest are Lutherans, Pentecostals, Baptists and others (Landguiden, 2005).

Economy

Agriculture accounts for a little less than 50 % of the gross domestic product (GDP) and it is in this sector that two thirds of the population earn their liveli-hood. Most of them are self-sufficient, living on small "chambas" using old-fashioned tools. The proceeds are low and production is highly dependent on weather conditions since artificial irrigation is scarce. Other important sectors are manufacturing, tourism, mining and industry (Sida, 1999; Landguiden, 2005). Ac-cording to gross economic and social indicators, Tanzania is ranked as one of the world’s poorest countries. In 1983 the rural poverty was 65 % but in the mid 1990s it had declined to 50 % (Sida, 1999). Figures from 2000/2001 show only a modest decline in poverty over the past ten years, and significant discrepancies between urban and rural areas. In rural areas, poverty is much higher, 39 %, than for example in Dar es Salaam where it is 18 % (Sida, 2004). The country’s econ-omy is heavily dependent on financial aid from other countries (Landguiden, 2005).

Health care

In the 1960s, under the socialist regime, a national health care system was estab-lished in Tanzania. The ambition was to offer free health care to all citizens. Un-fortunately however, due to the large budget cuts in the 1980s, this was not real-ised. Today, the Tanzanians pay fees to visit the doctor and there are shortages of medicines. Missionary health care and traditional healers complement the state health care (ibid) and there is a great shortage of doctors - only two per 100 000 inhabitants. The population growth is 1,8 % and a new born has a life-expectancy of 46 years (Sida, 2005). The most common diseases are malaria, tuberculosis, diphtheria and AIDS (Landguiden, 2005).

HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a virus that has spread quickly over the world since the beginning of the 1980s when it was first given serious attention. The virus has severe consequences for those who become infected, since they sooner or later acquire AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), which causes death. HIV comes in to the blood system and connects to, and attacks, cells

from the immunity system (T-lymphocytes) and it subsequently changes the DNA in the cells. In this way the virus becomes a permanent part of an infected per-son’s nuclear proteins. Thereafter follows a latent period during which time the virus awaits external stimuli from which it can begin to reproduce itself. When many cells have been affected the immunity system becomes greatly weakened and the body is incapable of defending itself from many of infections. At this stage the body can acquire opportunistic diseases, for example infections of the respiratory organs, the gastric system, the skin and the nervous system. The ind i-vidual will now have developed AIDS (Ericsson & Ericsson, 2002).

Since1983, when the first cases of AIDS were recorded in Tanzania, the HIV epi-demic has spread all through the country and affected all segments of the society. Towards the end of 2002 it was calculated that more than 1,8 million people were infected by HIV and almost 800 000 of these had developed AIDS. Data based on househo ld surveys indicated that the seroprevalence among adult Tanzanians is 7 % with large regional discrepancies (NACP, 2005). Over 80 % of HIV infections are transmitted primarily through heterosexual contacts. Although sexual beha v-iour is obviously a major determinant in the spread of HIV, there are also other contributing factors. For example, the risk for infection increases with the preva-lence of other sexually transmitted diseases and mother–to–child transmission is another important factor. Poverty and migration, due to political conflicts and wars, also increase the expansion of the epidemic in the society (Kapiga & Lugalla, 2002).

Social context of HIV/AIDS in Tanzania

In order to understand why HIV has spread to the extent to which it has in Tanza-nia, it is important to be aware of the social, political and economic changes that have occurred during the last four decades. After independence from the British in 1961, Tanzania adopted a socialist system in order to reduce the social differences and to stimulate economic growth. These policies led to improvements in the so-cial welfare of large groups in the rural areas and were by many regarded as a model. However, the result was a social and economic crisis in the beginning of the 1980s. Agricultural output and export revenues fell, the budget deficit in-creased and Tanzania became dependent on foreign aid in order to finance the na-tional budget. To deal with these problems, Tanzania adopted so called structural adjustment policies (SAPs) according to an agr eement with the World Bank in 1986. This policy centred on privatization, deregulation of the economy and de-valuation of the currency to stimulate foreign investors. The outcome of these market-oriented policies could hardly be described as a success, since major parts of the population saw their living conditions deteriorate due to rising unemplo y-ment and increasing inflation (Kapiga & Lugalla, 2002; Landguiden, 2005). The rapid expansion of HIV/AIDS is to some extent caused by the deterioration of social and economic conditions that has taken place during the last twenty years. The increasing costs of living and poverty have made worse the already existing gender inequalities and deepened women’s economic dependence on men. Many studies show that poorer women are more likely to practise high-risk sexual be-haviour and therefore many face an increased risk of HIV infection (Kapiga & Lugalla, 2002; Sida, 1999).

The economic impact of HIV/AIDS

The spread of HIV has had a profound impact on Tanzania's economic develop-ment. The relationship between HIV/AIDS and economic development is

com-plex. While it certainly has a profound negative effect on economic growth, the situation is accentuated by the fact that poorer countries have inadequate means to combat the epidemic. In addition, several studies point to the fact that poverty is a major factor which causes the spread of HIV. In the Kagera region of Tanzania, the BNP fell from 268 to 91 US dollars between 1983 and 1994. Even if there are several factors that explain this decline, it is widely believed that AIDS plays an important role (NACP, 2005).

For the single family in which a member falls ill with AIDS, this means disaster. Usually the woman in the family will have to take care of the sick family member, resulting in lower household incomes. The expenses for drugs and funerals are high and the economic burden is all the more heavy since Tanzania is one of the poorest countries in the world, where many people live on subsistence level. The capacity to cope wit h the cost of AIDS is often further undermined by stigma, which leads to social exclusion and weak support from local networks and com-munity resources (Russel, 2004; Tibaijuka 1997).

Prevention

So far neither vaccine nor cure for HIV/AIDS exists, so the only way of reducing the spread of the epidemic is to control the ways of infections. Knowledge of HIV/AIDS, of how it spreads and of possible ways of prevention, is absolutely vi-tal in order to make people realise the risks involved. Every section of communi-ties must co-operate to get through with the information (Egerö et al, 2001). The purpose of parts of the preventive work in African countries is to change the sexual behaviour in heterosexual relations. The information has been formed around three key messages: A-B-C or “Abstention”, “Be faithful” and “use Con-dom”. Abstention means that you should not engage in sexual relations before marriage and is above all intended for young people, for example young women who have sexual relations with older men. The other two messages build on the fact that fidelity and condom use reduce the risk of HIV- infection (ibid).

Preventive HIV-work among young people includes so called IEC-campaigns: in-formation, education and communication. The forms of these measures are often socially concreted and locally adapted and the focus is on empowerment and ca-pacity-building for behaviour change (Patel et al, 2002).

30 % of the HIV-positive women transfer their virus infection to their baby. Con-sequently preventive work also focuses on this relation. This work includes giving pre-natal care, the offer of anti-retroviral drugs and counselling on all available feeding options (Mc Growan & Shah, 2000).

Another important part of preventive HIV-work is testing and counselling. When people learn about their HIV-status, they normally want to protect both the m-selves and others and this positive change of behaviour can lead to a significant reduction in infected in areas with high HIV- incidence (Killow et al, 1998). Kagera region

The Kagera region is situated in north-western Tanzania on the western shore of Lake Victoria. Approximately 2,3 million people live in this part of the country and the regional capital is Bukoba. The first cases of AIDS in Tanzania were dis-covered in the Kagera Region in 1983. Since 1987 a research group, Kagera AIDS Research Project (KARP), has recorded the prevalence and the incidence of the

disease in Kagera and also studied changes in the sexual behaviour of the popula-tion (ibid). Prevenpopula-tion measures, such as health educapopula-tion, distribupopula-tion of con-doms, AIDS- information in schools, voluntary HIV-counselling and HIV-testing have been performed in the region. The results from these interventions show changes in sexual behaviour, for example an increase in the use of condoms, in continence, in keeping to one sexual partner and in voluntary HIV-testing (Lugalla et al, 2004).

Ndolage Hospital

In Muleba district, in which the Ndolage Hospital is situated, 56 km south of Bu-koba town (appendix 1), the estimated prevalence of HIV- infections has declined from 10 % in 1987 to 4,7 % in 1999 (KARP, 2005). The decrease in the preva-lence of HIV is not entirely due to fact that fewer are infected. It is also because people have died through AIDS due to a lack of anti-retroviral medicines and thus are no longer present in the statistics (The Economist, 2005).Ndolage Hospital is a voluntary agency run since 1928 by the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Tanza-nia (ELCT). There is also a nursing school which, since 1954, has been incorpo-rated within the hospital. The hospital is financed by patient fees, a small govern-ment grant and grants given by different donors, for example the Danish Mission and the United Evangelical Mission in Germany. Formerly, the hospital received many donations from abroad which helped keep the patient fees very low but nowadays, these donations have been reduced, making the hospital highly de-pendent on patient fees for running costs. This has reduced the availability of the service for the poor and has had a profound effect upon women and children (Kato, 2004).

The hospital has a capacity of 260 beds shared by six different wards, an opera-tion theatre, four health centres and it supervises twelve dispensaries. The hospital also runs five Maternal and child health care (MCH) clinics (ibid). The hospital’s catchments area is very homogenous being situated in Tanzania and nearly all of the patients belong to a tribe called Haya and speak their own language. Most of the people in this rural area are peasants.

PURPOSE

As shown above in the background section, HIV and AIDS have had very severe effects on life in large parts of Africa, not least in the Kagera region of Tanzania. In order to stop the spread of the virus, preventive work, in which nurses play a very important role, is vital. The purpose of this study was to investigate nurses’ preventive HIV-work in the Kagera region in Ta nzania.

The main research que stions are:

? How do nurses carry out their preventive HIV-work in the Ndolage area in the Kagera region of Tanzania?

? What are the problems and difficulties facing nurses in their daily work with HIV-prevention and how do they handle them?

? What are the main cultural factors that explain the ways in which the pre-ventive work is performed?

Limitations

The study does not include the investigation of preventive work that was carried out by professional groups other than nurses. Neither have I studied the preven-tion of HIV-infecpreven-tion among nurses or their workplace policy. Prevenpreven-tion of HIV- transmission through blood transfusion is also excluded from the study.

Definition

I use the term prevention as meaning preventing disease, ill health and complica-tions, as well as the promotion of health in all integrated parts of care. The pur-pose of prevention is to discover and take measures, not only concerning existing problems, but also for possible future problems and threats (Ehnfors et al, 1998).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This chapter will deal with the theoretical foundation on which this study is based and which in addition also was used as an instrument for understanding the pre-vailing culture on the countryside of north-western Tanzania. The founder of this theory, Madeleine Leininger (1995) has many years of experience in nur sing from different cultural environments. Her background as both a nurse and an anthro-pologist has resulted in a theory which illustrates the influence of culture over the health-care needs of individuals and the nursing care.

When Leininger began her career as a nurse in the 1940s in the United States, she realised that there were two important elements missing in nursing: care and cul-ture. She started by studying cultural differences concerning the view of nursing in both western and non-western cultures and this resulted in a theory of transcul-tural care - Culture Care Theory. The aim of transcultranscul-tural care is to persuade nurses to move from a unicultural point of view to a holistic and multicultural per-spective. By this, Leininger means that nurses, in order to perceive the patient's whole needs, must realise that there are not one single but many different cultures that affect the patient’s caring needs. Leininger aimed at pointing out the impact of culture on the behaviour of the individual as well as showing that the nurse has to offer care adapted to the prevailing culture in order to meet the needs of the pa-tients and, also, to be able to take ethical aspects into consideration (Leininger, 1995).

Leininger defines caring as an activity with the purpose of giving support or assis-tance to an individual or a group of people. Care is, according to Leininger, the very unique essence of nursing and is always to be found in a cultural context.

Culture is defined as ways of life of individuals or groups with respect to values,

conceptions, norms and actions. These ways of life are learned and passed on within the group and across generations. Culture could also be described as a framework for human behaviour and as a tool for solving our problems (Lein-inger, 1995).

Within culture Leininger distinguishes two different perspectives - emic and etic. Different cultures have their own perceptions and cultural insights which is knowledge gained from the inside of the environment, an emic perspective. It is essential that nurses gain access to, and an understanding of these emic perspec-tives. All too often, such knowledge is not made available to people not fully

trusted by the individual belonging to a special culture and the nurse can therefore not gain insight to the patient's "secret" way of thought. Emic is derived from the knowledge of somebody inside the cultural environment in question, while etic is derived from a more universal point of view outside the culture. Nurses mostly have an etic perspective in their profession. Ethnohistory and environmental con-text are, apart from culture, two central concepts when studying care from a cul-tural perspective. Environmental context comprises physical, ecological, socio-political and cultural settings, which give meaning to how care manifests itself among human beings. Ethnohistory is derived from the historic incidents and ex-periences among individuals or groups of people, which explain human patterns of living within special cultural contexts over short or long periods of time (ibid). In order to help nurses understand what elements that influence the cultural envi-ronment of the patient, Leininger has developed a model, the so called Sunrise

Model. This model can be used as a cognitive map of the culture care theory to

fa-cilitate trans-cultural care. The Sunrise Model shows how the structural, cultural and social dimensions (seven factors shown in appendix 2) affect the patterns and practices of nursing care and thereby the state of the patients’ health. Furthermore, the model shows how care in a given cultural context is influenced in part by tra-ditional generic care as well as by the professional nursing care. Included in the model are also three major modalities: preservation/maintenance, accommoda-tion/negotiation and repatterning/restructuring with respect to culture care. The purposes of these are to guide nursing judgment or actions to provide cultural con-gruent care and in turn to be beneficial to the people nurses serve. The Sunrise Model is normative in the sense that Leininger insists that nurses should be aware of the importance of social and cultural factors and the adva ntages to be found from adapting traditional nursing (ibid).

METHOD

In this chapter I will begin by explaining my choice of method. Following this, I will continue with my selection and mode of procedure in collecting data and conclude with my analytical procedure. As Dahlgren et al (2004) recommends, I will write in an active form, I- form, in this chapter.

My choice of method was based on the fact that the study was made as a Minor

Field Study (MFS) in a developing country. The aim of the MFS study is to gain

understanding of which preventative measures nurses at the Ndolage Hospital adopt with regards to HIV. Dahlgren et al (2004) writes that in order to investigate phenomena unknown to the researcher, a qualitative method is the most suitable. A qualitative approach makes for a deeper understanding as to the insight people have of themselves and of their environment. The goal is to conceptualise the meaning of phenomena and human activity and also to discover new concepts, hypothesis and theories.

I chose ethnonursing as a qualitative method first and foremost because it is ex-tremely useful when studying nursing phenomena in natural contexts and envi-ronments. It is a method also most suitable for situations where prior knowledge is limited. The aim of ethnonursing is to present a holistic illustration of the culture and the impact this has on the nurse's way of working (Leininger, 2001).

Lein-inger, who developed this method defines ethnonursing as ”a qualitative research

method using naturalistic, open discoveries, and largely inductive modes to document, describe, explain, and interpret informants´ worldview, meanings and symbols, and life experiences as they bear upon actual or potential nursing phe-nomena” (Leininger, 1997, p 42). Her purpose with her method is to guide nurses

towards a deeper understanding of transcultural nursing. The aim of ethnonursing is to understand the diversity and universality of care, i e to discover differences and similarities in nursing. In order to achieve this goal, it is essential to illustrate and differentiate between emic and etic data which stand for different perspectives of culture. Leininger has also developed tools and strategies that can be used in the method, for example her Stranger-Friend Enabler that is meant to be a help for the researcher to move from a stranger to a friend. I didn’t use any of these tools in the study (Leininger, 2001).

Selection

An ethnonursing study requires both key informants and general informants. In a mini study it is recommended to use between six and eight key informants and be-tween twelve and sixteen general informants. Key informants are people who have reliable and relevant knowledge of the field on which the study focuses. General informants have only broad insight and shallower depth of knowledge concerning the field of study. Information from both key and general informants facilitates the identification the diversity or the universality of ideas concerned with the care of humans (Leininger, 2001). The criteria used in selecting key in-formants for the study was that they worked in the Ndolage Hospital as nurses, that they were knowledgeable concerning prevention of HIV and that they could speak English. Regarding general informants, the requirements were much the same but without the necessity of special working knowledge on the preve ntion of HIV.

With the help of a gate-keeper, a person who smoothes the way forward for a re-searcher (Polit et al, 2001), I was able to start my observations at the hospital soon after I had arrived at Ndolage towards the end of July. I made contact with my first informant through general observations and the many informal conversations that arose. I chose other informants though the so called snowballing technique which means that the first informant is used to identify the next informant and so forth (Dahlgren et al, 2004).

The six key informants all worked as counsellors, which meant that they had re-ceived advanced training and are responsible for testing for HIV and giving coun-cil on HIV. The two general informants were ordinary nurses working at the Ndolage Hospital who had no special working tasks involving the prevention of HIV.

Gathering data

The gathering of data was performed during August and September 2005 at the Ndolage Hospital. Suitable methods with which to gather data within the field of ethnonursing are participant observation and interviewing. The use of several means of gathering information, so called triangulation, increases the credibility of a study in so much as it presents the opportunity of comparing and evaluating gathered data. In this way, both conscious and subconscious knowledge will be made available (Dahlgren et al, 2004; Leininger, 2001). The gathering methods I used were for the most part, participant observation and interviewing. In order to gather additional information, I analysed the various official regulative

frame-works for nurses. These methods made possible the gathering of both emic and etic data.

During the spring of 2005, prior to departing for Tanzania, I spent approximately four weeks studying literature on the relevant subjects. Dahlgren et al (2004) stresses the importance of being thoroughly prepared on subjects on which one in-tends to interview.

Participant observation

Participant observation is usually more associated with anthropology but this method can be used in other areas of study. The method means that the researcher observes and follows a group of individuals in order for example to learn and un-derstand its' culture, social patterns and work routine (Dahlberg, 1997). The ob-servations allow for an inside perspective of the subject being studied. This hap-pens through a mixture of personal experiences, observations and informal discus-sions (Dahlgren, 2004).

The first two weeks in Ndolage I began with participant observation in order to gain a general impression of how hospital work was organised. I followed nurses in their daily work on the wards which gave me a better understanding of the con-texts. The field notes I made both during the day and at the end of each working day focused on the purpose of the study and the components in the Sunrise model. I observed both the behaviour of the nurses and the circumstances in which the beha viour took place. This notes served as the base for my observational data. By the third week I had identified two of the key informants after which, my observa-tions centred around studying these nurses in their work, with HIV prevention. I did this in order to gain an understanding of what they were doing and how they went about their tasks. The remaining seven weeks, when not interviewing or transcribing, were used for observational work.

Interviews

Qualitative interviews aim at gaining a broader understanding of a phenomena as well as an inside, emic, perspective. Characteristic for this kind of interview are the open-ended questions which means that one encourages the informants to speak freely in their own words with the dual aim of gathering information and persuading them to be a part of the interview and share knowledge (ibid). The interviewing started during the fourth week of my stay in Ndolage when I used a semi-structured interview guide based on the aims of the research project and also on Leininger's Sunrise Model (appendix 3). A pilot interview was made with one of the key informants with a view to ascertaining the validity of the guide and checking to see if adjustments were needed. I had not intended to in-clude the pilot interview in the study, but the answers were so detailed that I thought it fitting that they be included.

The interviews lasted an average of 90 minutes and were held in English which is the standard language used in Tanzania for nursing education and is also the lan-guage used in the field of medicine. The interviewing was fairly free in order to gather as much information as possible, but I was careful in making sure that all the subjects on which I had planned to interview were covered. I made a prelimi-nary analysis after each interview in order that newly surmised knowledge could be used in forthcoming interviews (ibid). In a similar fashion, I developed my

in-terview guide somewhat from information that shed light on areas and subjects formerly not included.

At the beginning of each interview I made small-talk with the informant on eve-ryday matters in order to become familiar, which is something Kvale (1997) rec-ommends in order to create a pleasant atmosphere. At the conclusion of the inter-view, I gathered background information on factors concerning age, years of em-ployment etc. These subjects can sometimes be regarded as sensitive and personal so starting the interview with such information is not recommended (Dahlgren et al, 2004). Kvale (1997) advises concluding an interview by asking the informant if he or she has any question and this was a tactic that I adopted.

A total of eight nurses/midwives (nearly all nurses in the hospital were also quali-fied midwives irrespective of whether or not they worked in this field) were inter-viewed, five of whom were women and three men. Their ages varied between 28 and 40 and their working experience varied between 2 and 13 years. Four of the six key informants worked both as nurses and counsellors and two worked full-time as counsellors and other HIV related work. The two general informants worked as ordinary nurses. I met with two of the key informants on numerous oc-casions besides during their formal interviews in order to obtain a relevant in-depth insight as recommended by Leininger (2001).

The informants proposed the times for the interviews while I chose the venues which resulted in six of the interviews being held in my rooms I Ndolage which offered a secluded place. Two of the interviews took place in the hospital in pri-vate rooms.

Data analysis

The interviews were taped and afterwards transcribed verbatim, which means that the recorded material was transferred into text. Since I did not have access to a computer in Ndolage the transcripts were made by hand. In order to check for mistakes, I listened to the recordings a second time while reading the transcripts. Once the interviews had been transcribed, it was the written text that formed the basis for further work and analysis (Kvale, 1997).

Leininger (2001) divides her analysis of qualitative data into four phases, which I have tried to follow in my work. During the first phase I documented and gathered data from interviews and participant observations. While the first phase was still proceeding, I began the second phase, where, based on the gathered data, I started to identify descriptions and categories based on the gathered data. This meant that I read the text several times in order to be well acquainted with it and to receive an initial understanding of it. I followed this procedure after each interview as well as after all the interviews and observations were completed. After each read-ing I marked interestread-ing places in the margin. In the material of gathered data I compared similarities and differences. By going back to the informants to ask again about information which had been given in the interview or been noted while observing, I could either confirm or reject as invalid the information. I car-ried out the major part of the second phase in Tanzania because I wanted to have this as a background for further data gathering. According to Dahlgren et al (2004) analysis of qualitative material is a permanently ongoing process. Gather-ing of data, reflection on the research process and analysis of new information are interwoven in a joint activity for the researcher while performing field work.

In the third phase, I focused on finding patterns in the categorisations derived from the second phase. During this phase, which was carried out in Sweden dur-ing Autumn 2005, the material was grouped accorddur-ing to the seven perspectives used in Leininger’s Sunrise model and according to the nurses’ major tasks of work. Then I copied the original transcripts, reread and regrouped the material and compared this with the first groups. This procedure was done in order to find out if there was any discrepancy between the groups. To make the material more tan-gible, I then cut out the relevant parts from the interviews and observations and put them into heaps on the floor so that a physical pattern became visible. After-wards, I checked that the result of the analysis answered the study's subjects in question and covered all the perspectives in Leininger’s Sunrise model. The result from the third phase will be presented in the next chapter.

In the fourth and final phase of the data analysis, I spent time on creative thought which resulted in three major abstract themes. These themes arose from previous phases of the analysis and therefore also from Leininger's sunrise model. A fusion of certain of Leininger's perspectives was effected which subsequently proved to have inter-relating connections within aspects of nurses’ work. These three themes will be presented in the discussion of the result.

Ethical aspects

Several ethical aspects were taken into consideration before performing the study. Working as an outsider in a totally new environment, with a very different set of cultural rules compared to those experienced so far, I had to have deep ethical awareness. I went abroad and worked as a student on my own, but I had to take into careful consideration the fact that I might be looked upon as a representative of the white, western culture (Juntunen, 2000).

Before each interview the informants signed an agreement form, giving them in-formation about the purpose of the study, stating that they would stay confidential and that they could leave the study whenever they wanted to without giving any explanation (appendix 4). The informants also had to give permission for the in-terviews to be tape recorded. In the report, no information has been given which could be traced back to a specific informant. To be able to protect the anonymity of the informants, the figures chosen to represent the informants are randomised and give no hint of the order of the interviews.

I obtained ethical permission to perform the study from the ethical appeal board at Malmö University during the spring of 2005. The Swedish church, the General Secretary of the North-western department of ELCT in Tanzania and the head master of Ndolage nursing school gave their approval during the spring of 2005 to my request to come to Ndolage to perform the study. When I had arrived at Ndolage the doctor-in-charge at the hospital also gave his approval.

RESULTS

In this chapter the answers to the questions in the study will be accounted for, ac-cording to the data gathered in Tanzania, which preventive work the nurses carry out, and how and why they do it.

The result is based on eight formal interviews and participating observations dur-ing two months, in which are included informal interviews and studies of official regulations. In the account of the results, which follows below, I will not distin-guish between data received from the different methods of gathering. The presen-tation is an attempt to give a comprehensive picture, partly with the purpose of describing the context where in the nurses´ work.

The result is divided into three main groups based on the different parts of the nurses’ preventive work. Those three groups, health education, HIV-testing and mother-to-child, are presented from seven different angles, all derived from Lein-inger's Sunrise model as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Analytical frame work of nurses’ preventive work

Dimensions Types of nurses’ preventive HIV-work

Health education HIV-test Mother-to-child

Technological fac-tors Transport Technical Equipment Transport Test ability Transport Test ability Single dose

Religious and phi-losophical factors

Abstention, Be faithful and (Condoms)

Test before marry

Kinship and social factors

Family structure- Patriarchal

Relatives

Divorce Family structure- Patriarchal Husbands’ neglect Cultural values and lifeways Behavioural change Stigma Roomers Multiple partners Behavioural change Mens’ neglect Stigma breastfeeding TBA

Political and legal factors Government pro-grammes Guidelines Government pro-grammes Guidelines Government pro-grammes Guidelines

Economic factors Poverty- Patient Staff Foreign aid NGO Government Free test NGO Government Feeding options Free service Educational fac-tors Educational level Language Knowledge Educational level Language Counselling Educational level Language Knowledge Health education

By health education is meant the kind of work nurses carry out when teaching and informing in different contexts. The target group here is not a specific one, more the public at large, although relatives of HIV-positive patients form a certain tar-get group in addition to other groups at risk.

Technological factors

To travel to many of the information meetings held for bigger groups that the nurse is responsible for, they either go by motorbike or on foot. The nurse may di-rect people who want to take a HIV-test to other hospitals should it be found more convenient or she could bring testing equipment herself to a certain group who wants to undergo a HIV-test. This she does because in the countryside of north-western Tanzania there are huge transportation difficulties, due to the infra struc-ture being underdeveloped and with very fe w bus routes or car owners, which of

course reduce people’s possibilities to go to the hospital. Many people living in this area are peasants who earn practically no money at all and in consequence could not afford any means of transport should there happen to be such in exis-tence.

“…and the other thing is that it’s so expensive, the way of transportation, and they can’t finance it.” (Informant 5)

When teaching individuals or groups, the nurses rely only on themselves to bring the message across to their audience. They do not have the use of any technical equipment such as over head projectors or printed material such as brochures.

Religious and philosophical factors

An important part of the nurses’ preventive HIV work is to teach ABC. The nurse does not focus her teaching on condoms and how they are used, but on faithful-ness and abstention. The target group for teaching the use of condoms is not the general public, but married couples where one or both parties are HIV-positive. This shows that the values of the Lutheran church, ELCT, partly limit the work of the nurses. However, some of the nurses point out that they adjust their teaching to current conditions and accordingly, they sometimes teach about condoms to people who are not married. The Ndolage hospital is run by ELCT and the staff is obliged to follow the policy and the Christian set of values that this organisation support. ELCT fear that if you teach how to use a condom to prevent HIV trans-mission, people may misinterpret the message and feel free to have many sexual contacts.

“The church says that we are not supposed to teach the people about how to use condoms. But the government say that you have to use condoms. So it’s confusing, but we are cancellers. We have to teach them those main gears. That is to use condoms, stay away from sex (…) and to be faithful.” (Informant 8)

Kinship and social factors

Teaching and prevention of HIV often includes the whole family. However it is the patient’s own decision to tell his or her next of kin that he/she is HIV-positive, but if and when they have done so, the whole family is offered education. This procedure is explained by the fact that the average family in Tanzania lives very closely together in a very limited space. Therefore it is extremely important that the rest of the family is informed if one family member is HIV-positive. Generally it is family members who take care of the AIDS-patient and of course it is most important that they are aware of how the disease is transmitted in order to be able to protect themselves and to prevent further contagion. That the sick person is taken care of at home is mainly due to the prevailing poverty; there are not enough hospital beds and people often can not afford to pay for the hospital treat-ment that can be obtained.

“…because after discharge we are not longer staying with the patient, the relative will take care at home. So because of the contagion we have to teach the relative so they understand. (...) We also have to teach the relatives about how the disease is spread.” (Informant 5)

A difficult part of the nurses’ informative work is that which is directed specifi-cally towards women. The nurses are greatly aware of women’s subordinate posi-tion in society and take this seriously into consideraposi-tion in their work. An appar-ent problem is that women often do not dare to tell their husbands that they are HIV-positive. Therefore nurses endeavour to strengthen women to persuade them

to tell their husbands and the rest of the family; this being a condition for increas-ing understandincreas-ing by those affected. The main reason for these difficulties is that family structure in Tanzania is strictly patriarchal, especially in rural areas. Men bring an income to the family through wage earning while women tend to stay at home looking after the children and cultivating their small- holdings. This leads to the fact that most women are economically dependent on their husbands. In Tan-zania there is also a cultural tradition to pay more attention to the views of older people than to those of the younger ones say, which confirms women’s subordi-nate position.

“Yes, we are teaching, but it’s still a problem. Many women are still depending on men, it’s still a problem. (…) Yes, even about sex. When everyone can come and say:

-I want to h ave sex with you.

And you say yes, yes. They are taught to say –no.” (Informant 4) Cultural values and lifeways

The nurses teach that people are to have only one sexual partner or abstain totally from sexual relations in order to decrease the transmitting of the disease. If people can not live according to those rules, the nurses then recommend the use of con-doms. This teaching is founded in the Christian message as mentioned above but also in the prevalent cultural circumstances in Tanzania, since it is a rather com-mon practice that the man marries more than one wife. Cultural practice also al-lows the man to have numerous sexual relations outside his marriage, which is not an unusual phenomenon.

“We are teaching them to use protection, it’s condom. And to stop their sexual habit, if you can’t stop it you have to use condom.” (Informant 1)

“And for male it’s no problem to have other wives or female outside. But for female according to our culture it’s impossible for the male to know that maybe his wife has a boyfriend outside.” (In-formant 6)

The nurses focus part of their preventive work on persuading people to change their behaviour. This work includes the identification of risk categories, especially exposed to contagion, such as fishermen, students, alcohol users and drivers. For example, people who drink alcohol are considered to be at greater risk because they may loose their judgement and perhaps not protect themselves when entering into sexual activity. These groups are given advice and education about how their behaviour may put them at danger. Reduce the use of alcohol and drugs, not be-come unemployed, not have many sexual contacts and be faithful to your partner are some of the messages brought to the patients in order to make them under-stand the importance of changing their behaviour.

”We educate the people to change their behaviour to prevent to get HIV. Some with drug, polyga-miefamily, so we advice them to change (…) if somebody drink alcohol they are not aware so they can play sex without protection. We are advising them to trust in God. To have a business (…) then they have no time to have sexual. Because if you are doing anything that can keep them busy to remove that desire of having sex. And some others they do play sex because they don’t have nothing so they get money for their life.” (Informant 1)

The education carried out by the nurses also aims at reducing rumours spread about HIV. To explain how the virus is spread, and that HIV is a disease with which anybody could be stricken, is a way of combating those rumours. The nurses want people to come to the hospital for HIV-testing, and to receive medica-tion and informamedica-tion about with which kind of disease they have been infected

and why so. Accordingly, it is extremely important that there are no false notions are prevailing, which may lead to people turning to ”traditional healers” where they will be subject to treatment that will not help them.

”Whenever the patient comes to get tested and found that he or she is positive. She may think that she is withed and there is times when they go to the traditional healers. But it’s not so common (…) we tell them that it’s not because of a witch. We tell them that it’s like any other disease.” (In-formant 8)

HIV is a disease, which is highly stigmatising. People dare not tell others that they are infected because they fear the consequences. Previously it was common be-haviour to exclude HIV-positive persons from the community, they were not al-lowed to share food or glasses or blankets with the rest of the family. But as years have gone by, the stigma has weakened and the HIV-positive patients’ situation has improved. The nurses are fully aware of the prevailing stigmatisation and are of course endeavouring to minimise it. If the stigmatisation is reduced, people may find it easier to speak openly about the contagion, which could lead to a re-duction of the transmittance of the infection. Accordingly, informing and teaching about HIV to the general public as well as to the family members of a HIV-positive patient has the highest priority in addition to supporting the patient when he/she is to tell his/her family about a positive test result.

“The stigma in the community can be reduced in many ways…if the client can be open to her and the relatives it can reduce also the stigma. And what we are doing is the teaching relatives.” (In-formant 4)

Political and legal factors

The government has realised the great impact of the spreading of HIV and the kind of threat it poses on the country. They are therefore educating counsellors, who are to give advice on HIV and AIDS as well as to perform the tests. At the hospital there are six nurses and one doctor who are working as counsellors, two of whom are full time employed and the rest working according to a duty roster system. The two full time-nurses are employed by the Danish and German churches’ missionary organisation, NGO. The nurses follow the guidelines for medical workers distributed by the Ministry of Health. The guide lines explain how work within the national programme against AIDS is to be carried out in or-der to reduce the spreading of the virus and thus saving the lives of more people.

Economic factors

There are three different financiers within the preventive HIV work. The Tanza-nian government pays for the education of counsellors and for the antiretroviral treatment of pregnant women. The missionary organisation belonging to the Dan-ish church finance the AIDS Control Programme (ACP) where there is a full time employed nurse and the corresponding German organisation employs a nurse working only with counselling and testing of pregnant women.

Most nurses state that they can not perform their work in a satisfactory way be-cause of lack of staff. Due to shortage of finance of the hospital there is frequently only one nurse on each ward, responsible for 20-30 patients. The nurse can not find the time needed to give correct and detailed advice and to start a discussion with the patients. The nurses often have to choose between giving advice and test-ing more patients over havtest-ing a longer conversation with a stest-ingle patient, where the former alternative is most often the obvious choice. Likewise the nurse fre-quently has to give advice to groups instead of to individuals.

”I’m working but it’s very busy because I can’t go to everyone. And even on Monday and Friday the work I’m doing is very busy, because it can make me to misuse care for somebody. Because if there are many people (…) I think the time can be short whether to help those people who are out-side. So I’m doing which is possible” (Informant 4)

The nurses teach patients on several separate occasions in order to make them aware of the risks of transmitting the disease. One such occasion is connected to deliveries when mothers are asked to bring their own plastic sheets to lie upon during the expulsion phase. They are also asked to bring their own clothes and fabrics both for themselves and for the baby. After the delivery she is taught how to wash her blood-soiled garments so that nobody else will come in contact with her blood. The reason for this procedure is that there is a lack of both staff and material at the hospital.

”They ask about, they know that maybe after a delivery they wash the clothes from patients of this one who deliver. They say that, why t hey say it’s get infected when I wash the clothes. We answer that you can have a wound and in this the blood can come in. That is why nowadays we advice the mothers after delivery to wash their own clothes not to transmit.” (Informant 7)

Educational factors

The educational standard of the patients is often at a low level. Usually they have finished Primary School, only very few move on to Secondary School. Most pa-tients however are able to read and write. Nurses use methods such as role play, asking questio ns, discussion and sometimes ”brainstorming” when teaching, de-pending on what kind of group they are teaching. The recipients have no difficul-ties understanding because the nurses adapt the intellectual level to their audience.

“But even those who just go to primary school understand, they do. They understand what you are talking about.” (Informant 3)

The nurses speak at least three different languages in order to be able to commu-nicate in a satisfactory way with the patients. In the area surrounding the hospital in Ndolage mainly two languages are spoken: Kihaya and Swahili. The minority people, Haya comprise the dominating population in the close proximity of the hospital; their language being Kihaya. In Primary School Swahili is the teaching language which leads to the fact that most people are bilingual, although not all the old patients speak Swahili. The language used within the medical field is Eng-lish.

The knowledge of HIV among patients has increased during later years and nowadays most people know how HIV is transmitted and how to protect oneself from the virus. In one field ignorance is still extensive, how HIV can be transmit-ted from mother to child.

“Yes they know very well. They know. Even prevention they know.” (Informant 7)

HIV-testing

HIV-testing is directed towards the general public and the purpose is to persuade people to change their sexual behaviour after they have gained knowledge of their serostatus. The test is offered free of charge because financial reward should not be the reason why people do not wish to undertake the test.

Technological factors

To undergo the test the patients have to go to the hospital, which may be awkward due to the transportation difficulties mentioned above under the paragraph, Health education (see page 16).

Since several years past, the hospital has offered HIV-tests, two different types of test are used, Cappilius and Determine.

Religious and philosophical factors

One of the targets groups for testing are couples who are getting married. This custom has been common for a number of years, it was initiated when the go v-ernment asked the churches to take care of this. The procedure followed is that the parents of the couples usually decide that the young ones are to undergo the test and then the priest sends them to the hospital where it is carried out. When the re-sult is ready, it will be given both to the marrying couple and to the priest.

”Sometimes we get premarried. We get couple for premarried. They come for counselling and some they won´t tell themselves their serostatus. So they come and be counselled and be tested.” (Informant 6)

Kinship and social factors

The possibility of taking a HIV-test has caused some women to consider divorce when they have had a negative result in order to protect themselve s when kno w-ing that their husband have many sexual partners. It is true to say however that di-vorces are still very unusual due to the patriarchal family structure and the

women’s subordinate position, but the practice has started to occur.

“So when the mother maybe know that she can take the opportunity to make a test and to see if she is safe. And after knowing she can decide maybe if she will separate and safe her life.” (Informant 6)

Cultural values and lifeways

According to all nurses, there has been a shift in people’s behaviour in relation to HIV-testing. They say that HIV-testing has increased and that more people take the test than before.

”Yes there have been changed behaviours and the number who come to be tested before was very few. But now the number is rising. It means that people are very hoping then the previous days to test.” (Informant 4)

Not as many men as women undergo the test and this the nurses try to take care of in different ways, one way being that they have educated the chiefs in the villages and explained to them that they have to talk with the villagers about this subject so as to make them understand the importance of testing.

”…in the villages to inform those village leaders to talk about this issues so that people will be willing to come.” (Informant 2)

Political and legal factors

As mentioned above the government has distributed guidelines for how HIV-testing is to be carried out and is also responsible for educating those nurses who carry out that work.

Economic factors

The major part of the HIV-testing, which is free, is directed towards the general public, the purpose being that people should undergo the test voluntarily. The missionary organisation belonging to the Danish church runs ACP, working with HIV prevention, employs one nurse full time. The government pays for HIV-tests on patients staying at the hospital and for some of those who voluntarily come to the hospital for testing. In addition the government educate nurses and counsel-lors.

Educational factors

As mentioned above nurses take into consideration the educational level of their patients as well as their native tongue when carrying out the HIV-testing. Before testing a patient the nurses pre-counsel them in order to inform about HIV and check how much they already know. They also try to survey the backgrounds of their patients and thus find out whether they have been exposed to the infection or not. The nurse also asks if the patient has a relative with whom he/she could share the result and receive support from. After pre-counselling the blood sample is taken and analysed. The result of the analysis is given during post-counselling. Should the result be negative, the nurse focuses her information on the importance of avoiding risky behaviour in order to keep the patient negative. The nurse also explains the ”window period”, which means that the patient could be infected al-though antibodies are not yet present in blood samples. This makes it necessary to repeat the testing in three months to confirm the negative result. Should the result be positive the nurse prepares herself to meet the crisis reaction that the patient may show. She also directs her patients to groups run by ACP which give support to HIV-positive patients. When counselling, the nurse is not allowed to use any other means of assistance than her own voice. Communication is supposed to be face to face. Only nurses who are trained counsellors are allowed to perform the testing.

”I’m starting with health education, informing, watching the client, informing the client (…) then we educate them and about prevention and knowledge about the transmission (…) and if the client agree to be tested they will be tested. And then they wait for the results and then the results are given according to the condition (…) And after that we give also post-test counselling. And then you plan with the client what he wants to do. If he is negative then you counsel on how he will con-tinue to be negative and also on that he has to be tested after three month. Because that you a re being negative doesn’t mean that you are being sure negative. Because you can be in window p e-riod, so after three month we advice them to come for a second test.” (Informant 2)

Mother-to-child

With Mother-to-child is meant that the nurses direct their preventive work on in-hibiting the transmittance of the disease from mother to child. The child could be infected during pregnancy, delivery or breast feeding. The target group is specifi-cally pregnant women.

Technological factors

The government has decided that every pregnant woman is to be offered counsel-ling and testing through the programme,”Prevention of Mother to Child Transmis-sion” (PMTCT). In this way you can find women who are HIV-positive and offer them free antiretroviral treatment. This has been going on at the Ndolage hospital since August 2004. Medication, Nevirapine, is given as a single dose both to the mother and the newborn baby. Nevirapine reduces the viral load in the blood which limits the risk for the baby to be infected.

As mentioned above (see page 16) transportation difficulties make it hard for the mothers to come to the hospital. However the pregnant women need to come to the hospital several times during their pregnancy in order to have the foetuses checked. Therefore the nurses have the possibility of meeting the women although they do not come as often as recommended. Most women give birth at the hospital and this being another opportunity for HIV-testing the situation is that eventually most women are tested.

Kinship and social factors

The pregnant women come to the hospital to check their pregnancy and on these occasions they are offered an HIV-test. In this way many women are tested and not their husbands. If a woman is found to carry the virus, the nurse tries to per-suade the husband to take the test as well so that preventive information can also be given to him. The patriarchal family structure and women’s subordinate posi-tion however, as discussed above under the subtitle Health educaposi-tion, means that women who receive a positive test result are afraid to tell their husbands. Another reason explaining why husbands do not come to the hospital for testing is simply that they do not want to. The nurses put a great effort into persuading the men to undergo the test, as well as supporting the women to become strong enough to in-form their men about their serostatus. The nurses sometimes suggest that the cou-ple could come to Ndolage hospital together to be tested and in this case the nurses perform the tests on both of them as if they had not already done it on the woman. This serves as a way of avoiding that the woman has to tell about her re-sult to the husband on her own.

”We are facing the problems with the husbands; normally they don’t want to come. And we are not in that position t o say:

-Your wife came here, tested positive.

We are not allowed to do so. So what we are doing is to try to counsel the mother, and if she u n-derstands she will go and tell her husband about her serostatus and convince him to come. And then she will tell t he counsellor and the service will be given to the husband. And we are getting them even if they are not so many.” (Informant 2)

Cultural values and lifeways

The nurses have worked to persuade women to deliver at the hospital under hygi-enic conditions in order to reduce transmittance of HIV. This persuasive work has been necessary because in Tanzania women have traditionally delivered at home with the help of Traditional Birth Attendants (TBA:s). In rural areas there are many TBA:s, who usually do not have any medical education. They do however give women an opportunity to deliver at home and thus lower the costs, both for the actual deliverance and through not needing to pay for transport. Most TBA:s helping with deliveries do not use proper protective equipment to be able to stop the infection from spreading. This is the reason why the nurses at Ndolage hospi-tal have educated TBA:s not to deliver the babies at home but instead convince women about the importance of giving birth at the hospital. This has proved to be a good scheme since now about 90% of the women deliver at the hospital.

”Because nowadays they are strictly telling them not to deliver at home because of the risk of HIV transmission.”( Informant 3)

The nurses try to give the women strength enough to tell their families that they are infected. This is not only due to circumstances as the patriarchal culture in Tanzania, as discussed above (see page 17) but also because a HIV-positive woman is dissuaded from breast feeding in order to protect the baby. To make it

possible for the mother not to breastfeed she has to be able to give a plausible rea-son for this behaviour, which she might find difficult because she fears stigmatisa-tion. The custom in Tanzania is for the mothers to breastfeed and if a mother does not do so, she will be questioned. This leads to women breast feeding even when they know that it entails an increased risk for the baby. Fear of discrimination by their family and relations surpass fear of infecting the baby.

Political and legal factors

The government has decided that in all hospitals where deliveries are performed, prevention is to be practiced according to the guidelines developed for the Moth-ers and Children’s Health service, MCH.

Economic factors

For mothers, preventive HIV-treatment is free. The missionary organisation be-longing to the German church together with the Tanzanian government finance this programme, PMTCT.

The nurses give mothers advice on how to feed their babies and avoid transmitting HIV to them, the advice being as a first choice to substitute breast milk with either ”Milk Formula” or cow milk and secondary for the mother to breastfeed the baby exclusively for three months without giving any other food at all. The last choice is the one that most women choose: breastfeeding for six months and then starting directly to give exclusively normal food. The best choice would be the first alter-native, but due to prevailing conditions, i e great poverty in rural areas, the nurse has to inform about the next two alternatives as well.

”They can’t get cow milk, they are poor you know. And powder milk is very expensive. It’s very expensive. So they can’t pay because they are poor, so they can’t afford to buy it. So they try to breastfeed for at least six month, then they start with porridge.” (Informant 1)

Education factors

The nurses adapt their information to the educational level and the language spo-ken by their patients as mentioned above.

Several nurses relate that level of knowledge concerning the importance of per-forming HIV-tests on pregnant women have risen, the result being that almost everyone who is offered a test agrees to undergo it.

”For the first time the mothers they don’t wanted to be counselled or to be tested. We are just talk -ing together and then she said:

-Oh no, I’m afraid. I can’t be tested.

But know they come themselves and want to be tested. But there is some improvement. They are many and are coming” (Informant 8)

An overall analysis of the result leads to the conclusion that there are three differ-ent themes which stand out as most important to the nurses mode of work. The first theme concerns the patriarchal structure in society, that is to say the social and cultural conditions constituting a hindrance for the preventive HIV-work. The second theme concerns poverty in the Tanzanian society, which entails difficulties on many levels for the nurses. The third theme, as shown through the interviews, is how vital it is that preventive work focuses on changes of behaviour. In the dis-cussion of the result following below I will elaborate on those three themes.