F

ROM

F

AST TO

S

LOW

:

C

AN INFLUENCERS

MAKE US SHOP MORE SUSTAINABLY

?

A quantitative study investigating the impact of influencers and their communities on fashion purchase intent and circular behavior

BERTILSSON,ELLINOR

VANALPHEN,LAURA

School of Business, Society & Engineering Course: Master Thesis in Business

Administration

Course code: FOA403 15 cr

Supervisor: Cecilia Lindh Date: June 8, 2020

ABSTRACT

Date: June 8, 2020

Level: Master Thesis in Business Administration, 15 cr

Institution: School of Business, Society and Engineering, Mälardalen University Authors: Ellinor Bertilsson Laura van Alphen

(96/06/13) (94/12/31)

Title: From Fast to Slow: Can influencers make us shop more sustainably? Tutor: Professor Cecilia Lindh

Keywords: slow fashion, social media influencers, influencer marketing, sustainability, purchase intent, circular economy

Research How do social media influencers affect fashion purchase intent? questions: How is slow fashion behavior affected by social media influencers?

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to investigate the possible effects that social media influencers have on slow fashion behavior, in addition to explore the effects of social media influencers on fashion purchase intent.

Method: This research was conducted through a quantitative study and the data was collected using an online survey. The survey was constructed and distributed in collaboration with a research group at Mälardalen University.

Conclusion: This study confirms that influencers have the possibility to influence consumers’ behavior and provides initial insight into how their communities can affect consumers. The study concludes that influencers can persuade consumers to purchase fashion products online. However, there is ambiguity into how much influencers affect consumers. The study showed that the relationship between influencers and their communities is not clear, and especially how the two concepts interact in the way they influence consumers to behave more sustainably. Despite the complex relationship, both have the capability to positively and negatively affect consumers’ slow fashion behavior. While consumers may not employ all behaviors favorable in the slow fashion movement, any positive behavior will make a difference.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend the greatest of thanks to our supervisor Professor Cecilia Lindh for her invaluable guidance and advice throughout the entire process of writing this master thesis. Additionally, we would like to extend warm thanks to the other members of this research group. Cecile, Minda, Victoria, and Adelle, we could not have completed this study without the support

and suggestions provided by you. Lastly, we would like to thank Gustav R. Trocken for his unconditional support.

Lastly, we would like to thank everyone who participated in the survey from all over the world. Without your responses and commitment, the study would not have been possible.

Table of Contents Introduction 1 Research Problem 3 Purpose 4 Literature Review 5 Slow Fashion 5

Social Media Influencers 8

Purchase Intent 11 Hypothesis Development 12 Methodology 17 Research Design 17 Data Collection 18 Operationalization 21 Data Analysis 22

Validity and Reliability 24

Results 26 Correlations 27 Linear Regression 28 Multi-linear Regression 30 Discussion 33 Conclusions 37 Theoretical Implications 39 Managerial Implications 40 Future Research 40 Limitations 42 References 43 Appendices 51

Appendix A. Slow Fashion Familiarity 51

Appendix C. Sample Demographics 53

Appendix D. Operationalization. 55

Appendix E. Question Items Correlations 56

List of Figures

Figure 1: Conceptual Model for Hypothesis Testing 15

List of Tables

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for Constructs 23

Table 2: Cronbach’s Alpha of Constructs 26

Table 3: Spearman’s Rho Correlations for Linear Regression 27

Table 4: Linear Regression Results 29

1 Introduction

The fashion industry is currently experiencing a more dynamic and faster changing environment than ever before (Henninger, Alevizou, & Oates, 2016; Štefko & Steffek, 2018). Despite this, the fashion industry is continuously a huge global market with a revenue of US$1,839 billion worldwide in 2019 and has an expected growth rate of 4.8% per year landing on US$2,198 billion worldwide in 2023 (Lüdemann, 2019). Furthermore, in the eCommerce sector, the fashion category, including apparel, footwear, and bags and accessories, experienced the highest revenues of all categories in 2019, landing on US$620.6 billion. In the eCommerce sector the fashion category is expected to have an even higher growth rate of 9.8% per year landing on US$945.7 billion in 2023 (Rotar, 2020). When a market is as big as the fashion industry, problems arise. The fashion industry has received critique for a long time and most recently the criticism has been about the sustainability of the fashion industry as a whole. This is partly because of the environmental impacts of the fashion sector which ranks among the world’s most polluting industries (Shen, Li, Dong, & Perry, 2017). Even the big fast fashion companies are working towards a more sustainable future, including H&M who created and launched a conscious collection (Ritch, 2015).

Due to the demand from both consumers and companies to create a more sustainable future for the fashion industry, the concept of slow fashion has emerged. As a result of the novelty of this subject, slow fashion is still under researched, to the point that there is not yet an established definition (Štefko & Steffek, 2018). While several authors have tried to define slow fashion (Jung & Jin, 2014; Watson & Yan, 2013), Kate Fletcher who coined the term slow fashion in 2007 defines it as “designing, producing, consuming, and living better” (Fletcher, 2007). Additionally, Fletcher (2007) writes that slow fashion encompasses “designers, buyers, retailers, and consumers [that] are more aware of the impacts of products on workers, communities, and ecosystems”. One of the most

2 important things emphasized in slow fashion is the concept of quality over quantity (Legere & Kang, 2020). While fashion was always meant to be a personal expression, fast fashion companies have transformed the fashion industry into a machine where copies of clothing are being mass produced. Slow fashion emphasizes that clothing should be timeless and durable, in addition to still being used to enhance self-image perception (Štefko & Steffek, 2018).

Meanwhile, consumers’ activity on the internet increases. In the last decades, digitalization, and especially the appearance of the internet has tremendously increased the number of information-communication technologies available (Bognar, Puljic, & Kadezabek, 2019). The internet opened up the possibility of a whole new marketplace, online shopping for consumers. The global eCommerce revenue has increased drastically in the last few years and in 2019 the revenue was US$1,948.4 billion. The upcoming growth is expected to be 9% a year which leads to a revenue of US$2,883.4 billion in 2023 (Rotar, 2020). Due to digitalization and the internet, different social networking sites have emerged (Lou & Yuan, 2019). These developments not only changed consumer buying behavior, but also affected companies’ needs (Faith & Edwin, 2014). As a result of these developments, consumers are more informed, more curious, more demanding, and more knowledgeable about their wants (Faith & Edwin, 2014; Lou & Yuan, 2019). These social networking sites became important sources of information for consumers and subsequently changed into relevant online platforms for social media marketing activities (Alalwan, Rana, Dwivedi, & Algharabat, 2017; Stubb, Nyström, & Colliander, 2019).

In the last years, this relatively new phenomenon of social media marketing has been of interest for various academics and researchers (Stubb et al., 2019; Alalwan et al., 2017). Within this marketing field, there has been an increase in companies using social media influencers to promote a product or service (Ki & Kim, 2019; Lou & Yuan, 2019). This type of marketing is known as influencer marketing. It is defined by Lou and Yuan (2019) as “a marketing strategy that uses the

3 influence of key individuals or opinion leaders to drive consumers’ brand awareness and/or their purchasing decisions”. According to an analysis done by MediaKix (n.d) in 2016, brands worldwide spend around US$1.5 billion on influencer marketing and this is estimated to be US$15 billion in 2020 (Schomer, 2019). Especially in the fashion industry, the use of social media influencers (e.g. influencer marketing) has become a very common tool on different social networking sites (Casaló, Flavián, & Ibáñez-Sánchez, 2018; Schouten, Janssen, & Verspaget, 2020; Wiedmann, Hennigs, & Langner, 2010). Among the different social media platforms, Instagram is one of the most used platforms by companies in the fashion industry (Belanche, Flavián, & Ibáñez-Sánchez, 2020; MediaKix, n.d.). The development of social media entails new conditions for marketers, as they must consider not only how to act in this new digital environment, but also the new actors who are there to influence their customers.

Research Problem

Based on the previous introduction, there are two problems that led to the formulation of this research. First of all, the concept of slow fashion has just emerged. Due to this, there is insufficient information in the literature on this topic. It is considered as necessary to further explore this new phenomenon (Štefko & Steffek, 2018). Second, the concept of influencer marketing has been studied more during the last few years (Stubb et al., 2019; Alalwan et al., 2017). Particularly, there has been an expansion on the effect of influencer marketing on purchase intent, however there is still insufficient information in the literature regarding the effects of influencers on behavior. In addition, to our knowledge, there is no research done that looks at the possible effects influencers could have to change consumers’ fashion behavior towards a more sustainable approach that fits into the concept of slow fashion.

4

Purpose

Considering the recent development of influencer marketing and the emergence of slow fashion, the purpose of this paper is to investigate the possible effects that social media influencers have on slow fashion behavior, in addition to explore the effects of social media influencers on fashion purchase intent. In light off the research gap within slow fashion, we have developed the following research questions:

1. How do social media influencers affect fashion purchase intent? 2. How is slow fashion behavior affected by social media influencers?

With these questions this paper attempts to address the sustainability issues currently experienced in the fashion industry. It aims to contribute to the literature currently available about slow fashion while also advancing the knowledge about social media influencers. Additionally, available literature on slow fashion, purchase intent, and social media influencers will be used to develop a conceptual model. This study will focus on the consumption part of slow fashion behavior, as it is the most undeveloped part of slow fashion and the most related to social media influencers. Further, the paper will have the following structure. In the next section we will conduct an extensive literature review on the concepts covered in this paper, including a hypothesis development. Second, we will provide our methodological approach. Third, the results will be presented followed by the discussion and analysis of those results. Lastly, we will present our conclusions along with the implications and limitations of our research.

5 Literature Review

Slow Fashion

Despite the relative novelty of the concept of slow fashion, some research about the concept has been made. However, it may be important to start off by distinguishing what slow fashion is not. Fletcher (2010) argues that while slow fashion has often been discussed as only less fast than the regular fashion industry, it more importantly is an opportunity to segment and differentiate apparel in a contemporary way. Furthermore, while slow fashion first gained attention as the antithesis to fast fashion, it has later developed into a topic of its own (Jung & Jin, 2014). Moreover, it is important to make the distinction between the slow fashion movement and sustainable fashion and ethical fashion (Mukendi, Davies, McDonagh, & Glozer, 2020). Lundblad and Davies (2016) defined sustainable fashion as a way to “correct a variety of perceived wrongs in the fashion industry including animal cruelty, environmental damage and worker exploitation”. Furthermore, Joergens (2006) defined ethical fashion as “fashionable clothes that incorporate fair trade principles with sweatshop-free labour conditions while not harming the environment or workers by using biodegradable and organic cotton”. Both sustainable fashion and ethical fashion are more concerned with the production and distribution of fashion (Joergens, 2006; Lundblad & Davies, 2016), while the slow fashion movement incorporates the consumption and the recycling and reuse of clothes (Fletcher, 2007; Jung & Jin, 2014), which can be seen in the definition provided in the introduction. To clarify, the slow fashion movement combines sustainable and ethical fashion, while also including the consumption and designing of products (Fletcher, 2007; Jung & Jin, 2014). Adding on to these three definitions, a lot of research has investigated the fashion brands, the retailing of apparel, and the supply chain. However, little to no research has been conducted on what affects the purchasing decision of consumers buying sustainable fashion (Lundblad & Davies, 2016).

6 One of the first articles trying to conceptualize slow fashion was written by Jung and Jin (2014). Through a study of consumers, they found that slow fashion consumers' needs could be divided into five dimensions; equity, authenticity, localism, exclusivity, and functionality. Equity focused on the accessibility of the products through fair trade while authenticity emphasized that the fashion industry should be shifting towards craftsmanship and highly skilled production. Localism highlights the support of local businesses whilst exclusivity accentuates the want from consumers to have diverse clothing. Lastly, functionality focuses on the post-purchase stage for consumers and the way slow fashion clothing is used (Jung & Jin, 2014). All of these dimensions adhere to the definition originally used by Fletcher (2007) in terms of discussing all stages of the supply chain, from designing to consumption. These five dimensions were later used by Jung and Jin (2016) to investigate how these factors affect customer value. They found that only the exclusivity dimension was significant in creating customer value. However, they also found that consumers who perceived value in slow fashion products were more likely to purchase slow fashion items and were willing to pay a premium for these products. Jung and Jin (2016) also concluded that once a customer is willing to purchase slow fashion items, paying a higher price for the products is not an issue.

Legere and Kang (2020) investigated a different approach of consumer behavior into slow fashion by using self-concept theory and moral identity. They found that moral identity had a negative relationship on behavioral intentions towards slow fashion. Despite this result, Legere and Kang (2020) speculate that consumers purchase slow fashion because it is ‘the right thing to do’, rather than wanting to reveal that they do it for their own self-interest. This contradicts the study made by Lundblad and Davies (2016), who found that sustainable fashion consumers were more driven by their internal and egoistical drives rather than altruistic values. Additionally, Legere and Kang (2020) believe that as a result of the fashion industry having a reputation of being

7 environmentally unfriendly, consumers may have a hard time internally connecting that slow fashion is indeed worth paying a premium for. While there is still a dispute over how slow fashion consumers make their decisions regarding purchasing, the recent increase in published articles is starting to narrow the research gap. However, there has not been a significant amount of research into how digitalization may affect the slow fashion movement and specifically how influencer marketing can be used to further develop slow fashion.

Circular Economy. As the world becomes increasingly aware about sustainability issues, solutions are being presented as possible remedies to the issues. Circular economy is a concept that seems to have its roots back in the late 1970s (Geissdoerfer, Savaget, Bocken, & Hultink, 2017), but in recent years the concept has gained significant attention from both academics and practitioners (Kirchherr, Reike, & Hekkert, 2017). The number of published articles regarding circular economy has drastically increased during the latter half of the 2010s. Geissdoerfer et al., (2017) found that the number of publications on the Web of Science discussing the topic of circular economy increased from around 30 in 2014 to almost 110 in 2016. Both Geissdoerfer et al., (2017) and Kirchherr et al., (2017) conducted extensive literature reviews on the topic of circular economy in an attempt to conceptualize it. Geissdoerfer et al., (2017), ended up defining circular economy as “a regenerative system in which resource input and waste, emission, and energy leakage are minimised by slowing, closing, and narrowing material and energy loops. This can be achieved through long-lasting design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling.”. While academics consistently emphasize reducing as a part of circular economy, this is something that seems to be excluded from the discussion by practitioners (Kirchherr et al., 2017). Assumingly, this is due to practitioners not wanting to reduce consumption and an attempt to further economic growth (Kirchherr et al., 2017). The final goal of circular economy is to create a closed loop that excludes inputs into a system and eliminates possible waste leaving the system.

8 Further, the motivation is to make better use of our available resources (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). One industry that needs to move towards a circular economy is as previously mentioned the fashion industry. Specifically, the textile industry needs to move from the take-make-waste model that is most commonly used towards a more circular approach (Koszewska, 2018). While transitioning into a more circular business model is not easy, Fischer and Pascucci (2017) identified two different pathways fashion companies could use to employ a more circular business model and they argued that contracting, financial mechanisms, and coordination are the essential business elements necessary to change in order to develop a more circular production. The slow fashion movement and the concept of circular economy share several similar traits. The most important ones for this study are the slow fashion movements’ goal of reducing consumption through recycling and reusing (Fletcher, 2007) and the ultimate goal of circular economy which is to create a closed loop in the system (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017).

Social Media Influencers

The use of influencers in marketing activities has been around for many years. According to Erdogan (1999), companies have been using celebrities for endorsing their products since the late nineteenth century. Different studies have been conducted to identify opinion leaders. The use of celebrities in marketing communication is called celebrity endorsement, which Bergkvist & Zhou, (2016) defined as “an agreement between an individual who enjoys public recognition (a celebrity) and an entity (e.g., a brand) to use the celebrity for the purpose of promoting the entity”. Other researchers use the concept of opinion leaders, which refers to individuals that have a huge influence on the decision-making process of other people, as well as their attitude and behavior (Casaló et al., 2018; Grewal, Mehta, & Kardes, 2000). Besides celebrities and opinion leaders; friends, relatives, and even colleagues can be considered as influencers because they have an impact on consumers’ choices as well (Godes & Mayzlin, 2004). Even though researchers used

9 different terms to define an individual that has influence on people’s choices, behavior, and attitudes, previous research showed that influencers have been around for many years. However, nowadays the term ‘influencers’ is often in reference to social media influencers (Bognar et al., 2019), which is how it will be referred to in this paper. De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders (2017), refer to social media influencers as “people who have built a sizeable social network of people following them”. Social media influencers are seen as ‘regular people’ that gained a lot of followers by posting and creating content on social media platforms (Lou & Yuan, 2019), whereas celebrity influencers gained fame for their professional talents, such as being an actor, a supermodel, or an athlete (Schouten et al., 2020; Belanche et al., 2020). Compared to the use of celebrities, the use of social media influencers seems to be more effective (Schouten et al., 2020). A study done by Schouten et al. (2020), showed that consumers can better identify themselves with social media influencers and trust them more than celebrities.

In the last years, the popularity of social media influencers has grown dramatically among practitioners and researchers (Uzunoğlu & Misci Kip, 2014; Evans, Phua, Lim, & Jun, 2017; Lou & Yuan, 2019). However, scientific research about this phenomenon is still limited (Schouten et al., 2020; Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, 2019; Ki & Kim, 2019). Previous research showed that influencers have a significant impact on consumers’ behavior as well as their purchase intent (Bognar et al., 2019). Nonetheless, there are other factors involved in the effectiveness of influencers on consumers’ purchase intent and behavior, such as the followers’ trust in the influencer, the informative value of the generated post, the credibility of the influencer (Lou & Yuan, 2019), and the interactivity and personalization of a social media account (Alalwan et al., 2017). Besides, the perceived fit a consumer has with a social media account positively influences the consumer’s intention to follow given advice by an influencer (Casaló et al., 2018). Although there has been some research on influencer marketing and in particular the use and the effectiveness

10 of social media influencer, none of the research done to date has focused on the influence they could have on changing consumers’ behavior towards more sustainable consumption.

Community Behavior. Social media influencers are being used on different platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube (Audrezet, de Kerviler, & Guidry Moulard, 2018). Besides, the popularity of these different online platforms has grown over the last years and now have billions of users worldwide (Casaló, Flavián, & Ibáñez-Sánchez, 2017; Stubb, et al., 2019). According to eMarketer (2019), in 2019, there were around 2.95 billion people worldwide using any social media and it is expected to increase to 3.2 billion users by 2021. Social networking sites (e.g. social media) give consumers the possibility to share information and experiences of products (Park, Shin, & Ju, 2014). Moreover, they create online communities where consumers can connect with each other, as well as with brands (Wolny & Mueller, 2013). Nowadays, social media is used as one of the main sources of information for consumers’ purchasing decision process and an online community affects consumers’ behavior and their perception of a product or brand (Alalwan et al., 2017; Park & Cho, 2012). It not only became a source of information, but it also affected how customers receive information (Lou & Yuan, 2019). In addition, social media has caused a shift to a more empowered consumer (Diffley, Kearns, Bennett, & Kawalek, 2011). Due to the internet and social media, consumers became highly knowledgeable about products and became more involved in marketing activities (Diffley et al., 2011). Moreover, recommendations given by friends on social media are very powerful and as Diffley et al. (2011) stated, these recommendations in turn affect attitude. Other researchers focused on the effect that user’s participation on social networking sites has on brand awareness and brand attitude (Langaro, Rita, & de Fátima Salgueiro, 2015; Zheng, Cheung, Lee, & Liang, 2015). Moreover, there are companies, such as Patagonia, that together with brand ambassadors and influencers, try to encourage sustainable practices with the purpose of selling less and encourage consumers to repair

11 or hand down apparel (Bianchi, 2020). Providing consumers with more knowledge about sustainability could lead to a change in behavior, but currently it is unknown if the use of brand ambassadors or influencers in online communities is an effective way to communicate these practices (Yan, Henninger, Jones, & McCormick, 2020). However, most academics have focused on studying online brand communities with limited or no research investigating online communities surrounding a social media influencer. In this paper, community behavior will refer to the communities that surround an influencer, rather than a brand.

Purchase Intent

Purchase intent is one of the most commonly investigated subjects within the field of marketing. After all, having a company is about making money which is achieved through customers purchasing items. In 2015, Arslan and Zaman (2015) defined purchase intent as “the possibility that a consumer will purchase a product or service in the future”. Purchase intent is a complex subject because it is affected by many different factors, such as personal, psychological, and social factors. Additionally, demographics play a huge role when it comes to how consumers make purchasing decisions (Reddy & Reddy, 2010). Most purchase decisions follow five steps; need recognition, information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase decision, and post-purchase behavior. All consumers use at least one of these steps when making a purchasing decision (Rieke, Fowler, Chang, & Velikova, 2016). Considering the recent growth of digitalization, today’s retailing industry is more dynamic and because of the swift changes marketers must be very aware of what their consumers want (Reddy & Reddy, 2010).

Purchase intent has been investigated both in the field of influencer marketing and slow fashion. Within slow fashion, studies have shown that different factors affect the purchase intent of slow fashion (Jung & Jin, 2016; Legere & Kang, 2020), with a study also showing that consumers are willing to pay a premium for slow fashion items (Jung & Jin, 2016). The factors affecting purchase

12 intent in slow fashion include, but are not limited to, exclusivity and self-transformation (Jung & Jin, 2016; Legere & Kang, 2020). When it comes to influencer marketing, Lindh and Lisichkova (2017) found that the use of influencers is not enough to stimulate the online purchase intent from consumers, but it did increase the consumers’ willingness to ask experts for advice which subsequently increased purchase intent. However, Ki and Kim (2019) found a strong significant relationship between influencers and purchase intent. Furthermore, Chetioui, Benlafqih, and Lebdaoui (2020) found that different factors impact the attitudes towards fashion influencers, which subsequently positively impacts brand attitude and consumers’ purchase intent. They found that factors such as perceived credibility, perceived expertise, trust, and behavioral control positively impact the attitude towards fashion influencers (Chetioui et al., 2020).

Hypothesis Development

The essence of slow fashion is the focus on being sustainable through all stages of the clothing lifecycle, from designing and production to consumption and recycling/reusing of apparel (Fletcher, 2010). Despite this, clothing consumption is at an all-time high (Legere & Kang, 2020), and clothing that is not being reused or recycled are filling up the world’s landfills (Jung & Jin, 2014). The apparel industry in general is not focusing on reducing consumption levels, but is rather focusing on making the supply chain of the fashion industry more environmentally sustainable (Jung & Jin, 2014). However, the slow fashion movement strives to decrease the consumption of clothing and focus on a more sustainable overall approach. They encourage people to buy fewer clothing items at a higher quality and with more timeless designs. This increases the longevity of every apparel item and is often considered slow consumption (Jung & Jin, 2014; Štefko & Steffek, 2018). Slow consumption also follows the trend to strive towards a more circular economy. The focus of a circular economy is to make the whole production process more sustainable, but most importantly to add value after the normal user life of a product is over (Fischer & Pascucci, 2017).

13 The activities that can be used to add value include reusing, refurbishing, recycling, and maintaining. In order to easier achieve a circular economy, activities like maintenance of apparel are important since it is a part of the use phase (MacArthur, 2013). This shows that slow fashion and circular economy have several similar traits and focuses. Therefore, the constructs will be named based on the circular economy literature, as it is more widespread than slow fashion. In the context of this paper, circular buying refers to buying second hand, making the most of the clothes consumers’ own, etc., while circular selling refers to selling clothes to second hand, handing down or donating worn clothes, etc.

In contrast to slow consumption, influencers are consistently promoting the purchase of new products. In line with traditional marketing, influencers are used to promote new products. Either it could be through testing a new product on the market or simply receiving compensation for promoting a new product (De Veirman et al., 2017). Consumers are striving to mimic influencers’ behavior by purchasing items that they are recommending (Ki & Kim, 2019), and digital influencers have been found to increase consumers’ purchase intentions (Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, 2019). To our knowledge, no research has investigated how influencers can affect sustainable purchasing. Because of the focus on new consumption by influencers (De Veirman et al., 2017), it is expected that their power will outweigh the focus on longevity and slow consumption promoted in the slow fashion movement. Thus, the following hypotheses have been hypothesized:

H1a: Community behavior has a negative effect on circular buying H1b: Influencer influence has a negative effect on circular buying

Nevertheless, a trend seen from influencers is the increase of promotion of recycling and reselling of used clothes. Because influencers receive a lot of clothing items for free, their

14 wardrobes are increasingly growing without them using their clothes possibly more than once. Due to this, there has been a recent boom of resale fashion platforms. One example is Depop that sells pieces previously worn by influencers and other celebrities (Graddon, 2019). Other examples are Vinted and United Wardrobe. These apps provide consumers with apparel that is new to them, but at the same time, they decrease consumers’ purchasing of new fashion items and also extend the lifecycle of old items (Lang & Zhang, 2019). BCG (2019) conducted a survey that found that 44% of consumers who sell luxury goods online, do so because they want to empty their wardrobe. While no research has investigated how influencers may promote recycling and reusing of clothing items, the recent trend of more promotion of sustainable behavior should have an effect. Considering the increase in promotion of reusing and recycling of clothes from influencers, the following is hypothesized:

H2a: Community behavior has a positive effect on circular selling H2b: Influencer influence has a positive effect on circular selling

Furthermore, consumers tend to follow recommendations about a product or service given by an influencer, because the given information is perceived as reliable and trustworthy (Akar & Nasir, 2015; Bergkvist & Zhou, 2016; Lou & Yuan, 2019). According to Ki and Kim (2019), consumers have a desire to imitate an influencer which subsequently leads to a higher purchase intent. The more desire a consumer has to imitate, the more likely they are to purchase. Furthermore, Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández (2019) emphasize the effect that influencers have on consumer behavior and the purchase intent towards the advertised product. In addition, the perceived fit a consumer has with an influencer’s platform has a significant relation with purchase intent (Belanche et al., 2020). The more trust a consumer has towards an influencer, the more they follow a given recommendation, and the more inclined they are to buy the advertised product (Schouten et al., 2020; Casaló et al., 2018). According to Schouten et al. (2020), influencers have more effect

15 on consumers’ willingness to buy a product than celebrities have. The majority of the studies found that there is a positive relation between influencers and purchase intent (Bognar et al., 2019; Ki & Kim, 2019). However, as previously mentioned other research stated that the consulting of influencers is not enough to increase consumer purchase intent (Lindh & Lisichkova, 2017). Furthermore, online brand communities on social networking sites have been found to have a positive effect on brand attitude (Wang, Cao, & Park, 2019), which subsequently leads to an increase in purchase intent (Tiruwa, Yadav, & Suri, 2016; Wang et al., 2019). Previous research has found that influencers have a positive effect on online purchase intent and online communities have an intermediating effect on purchase intent (Ki & Kim, 2019; Tiruwa et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, the following hypotheses are constructed:

H3a: Community behavior has a positive effect on fashion purchase intent H3b: Influencer influence has a positive effect on fashion purchase intent

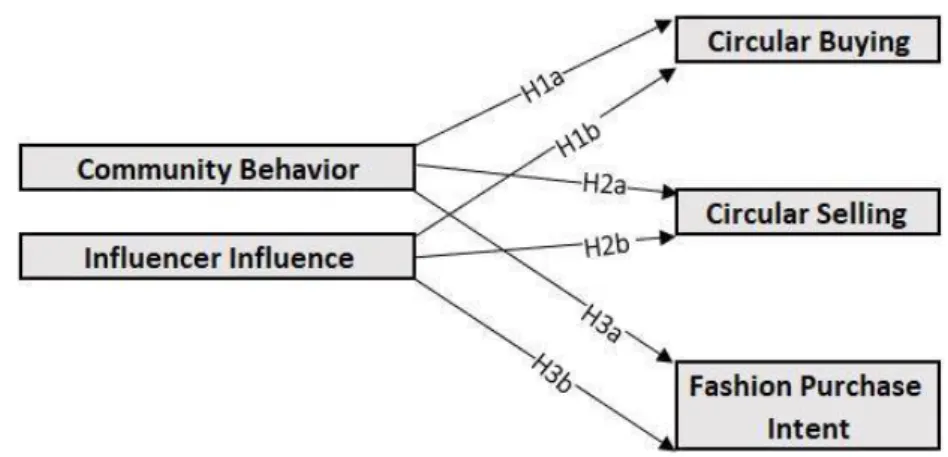

Based on these six hypotheses a conceptual model was developed. The model can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Conceptual Model for Hypothesis Testing

In H1a, H2a, and H3a community behavior is the independent variable with circular buying, circular selling, and fashion purchase intent as the dependent variable respectively. Second, in H1b,

16 H2b, and H3b influencer influence is the independent variable with circular buying, circular selling, and fashion purchase intent as the dependent variable respectively.

17 Methodology

Research Design

Positivism is the philosophical approach chosen for this study. This approach is the most commonly used in social science (Isaeva, Bachmann, Bristow, & Saunders, 2015), due to its aim to find the causal relationships between dynamics in social reality and to formulate universal laws (i.e. generalizations) (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2016, p. 135-138; Isaeva et al., 2015). This research orientation focuses on the belief that knowledge should be objective and based on observable and measurable facts and relationships (Isaeva, et al., 2015). Moreover, positivism argues to predict behavior and law-like generalizations are produced to explain the truth (Ghauri, Grønhaug, & Strange, 2020, p. 18). Additionally, according to the positivist approach, this study was conducted using a quantitative research design using a deductive theoretical development (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 135-138). A quantitative method was seen as most appropriate for the purpose of this study, to explore relationships between influencers, sustainable behavior, and purchase intent. Therefore, quantitative data is best suitable to answer the research questions (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 166-168). The deductive approach is generally used in quantitative research design because it builds upon existing literature to formulate hypotheses which can be tested empirically (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 19).

The data was collected through an online survey, complemented by an extensive literature review conducted with journal articles into the subjects of slow fashion and influencer marketing, and more specifically social media influencers. The online survey was deemed appropriate due to the likelihood of further reach and the possibility of a more diverse sample of respondents, in addition to being the most commonly used method with a positivist approach (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 135-138). Furthermore, the online survey was chosen in order to ensure that the researchers’ own values would not inflict on the results of the study, also according to the positivist approach

18 (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 135-138). The articles for the literature review were collected by searching different databases. The ones mainly used were Google Scholar, Emerald, Scopus, and

Academic Search Elite. Some of the search terms used were ‘slow fashion’, ‘sustainable fashion’, ‘influencer marketing’, ‘social media influencers’, and ‘celebrity endorsement’. Two literature

reviews on both celebrity endorsement and social media marketing were found.

Data Collection

The online survey was created and distributed as a collaboration of a research group at Mälardalen University. The research group consisted of six master students from Mälardalen University, one researcher from Mälardalen University and one PhD candidate from Örebro University. The six students were divided into three groups of two, all focusing on different aspects of slow fashion. Due to this research collaboration, not all question items in the survey are analyzed or mentioned in this study. The survey was translated from English into three different languages; French, German, and Spanish. These languages were chosen because they were believed to create the highest possible reach and target groups who would possibly not feel comfortable answering a survey in English, to further make the respondents more diverse. The translation to Spanish and French was conducted by two students in the research group and the German translation was made by a friend of a member in the research group. The translations were back-translated to ensure the best possible translation and understanding, and to ensure the validity of the study (Brislin, 1970). This back translation is an approach used to test the accuracy of a translation and to identify errors (Brislin, 1970).

The questionnaire was aimed at any respondent who has purchased apparel online. It was targeted at all genders and ages over 18 years. Additionally, all nationalities and professions were welcome to answer the survey. Again, to increase the diversity of the sample and possibly get a more representative sample. The survey was distributed mainly through personal messages on

19 platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and email. Additionally, posts were made on Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram to further the reach. Furthermore, collaborations were made with companies. One example is Slow Fashion World who distributed the survey among their community. In this study, a convenience sample was used, which is a commonly used sample in quantitative research to collect a large data set (Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim, 2016). This convenience sampling technique is a form of non-probability sampling (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 166). In addition, a snowball sampling method was employed and therefore the respondents to the survey were encouraged to spread the survey further (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 303). The snowball sampling method is a convenience sampling that can be used when the goal is to reach a large number of respondents by contacting a smaller number of respondents (Etikan et al., 2016). A limitation of this technique is to accurately determine the response rate (Johnstone & Lindh, 2018). Reminders were sent out to contact people who had not confirmed their responses to the survey. Reminders are generally speaking good to decrease the non-response and ensure a higher response rate (Bell, Bryman, & Harley, 2019, p. 236). Besides, it is also recommended by Dillman, Smyth, and Christian (2014), to send follow-ups earlier and more frequently when using an online survey.

As researchers, it is important to consider the ethical issues that arise when conducting research with humans as the research subject. The respondents to our survey were ensured of anonymity and informed consent was collected through the introductory text of the survey (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 243-245). The participants were introduced to the research project and informed that the study will only be used for scientific purposes and not commercially. No questions were asked in the questionnaire that could possibly be used to identify the identity of respondents. Findings are reported without any alterations being made, even if the result was not as expected (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 243-245).

20 The survey contained sixteen questions, including five questions regarding demographics. The demographics questions included questions about age, gender, nationality, level of education, and current profession. These questions were chosen to be able to give a background description of the sample of respondents. Additionally, due to the novelty of the concept of slow fashion, a question about the respondent’s familiarity with the concept was asked. Respondents were asked to answer ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘don’t know’ if they were familiar with the concept of slow fashion, and if they answered ‘yes’ they were asked to provide their opinions of the concept. The results show that only 28.1% of the respondents were familiar with the term slow fashion. The full distribution of this question can be found in Appendix A.

The questionnaire was published on the 29th of November, 2019 and data was collected until the closure of the questionnaire on the 15th of April, 2020. The sample consisted of 717 respondents, but one of the respondents was removed from the analysis because none of the question items were answered. The sample consisted of 69.5% women and 29.5% men. 1% of the sample did not want to disclose or chose the option other. The age of the respondents was dominated by people born between 1980-1999, with 79.9% of the sample being in that age group. The respondents were from 59 different countries. The full list of countries can be found in Appendix B. The countries that were mostly represented were Sweden with 32% of the respondents, followed by Mexico and the Netherlands with 14% and 13% respectively. All countries with less than ten respondents were merged into one category that is called “other”, to ensure that respondents could not be identified based on their nationality. More information about the demographics of the sample can be found in Appendix C. Age, gender, and education were tested with cross tabulations to ensure that there were no significant differences in the sample due to demographic characteristics. No significant differences were found.

21

Operationalization

The question items used were mostly based on existing literature, but some were slightly modified to fit the purpose of the study. Moreover, some question items were made in collaboration with the research project group, but based on existing literature. To measure community behavior two question items were asked: one to measure if being part of an online community is important; and one to measure if connecting with people online that have similar values is important. These items were based on previous literature on online communities and social networking sites (Zhou, 2011; Bishop, 2007; Liu, Shao, & Fan, 2018). The independent variable influencer influence measures the likeliness a customer will buy or like a product or brand based on a positive review given by an influencer. This variable is measured by the following two question items, ‘I am more

likely to buy a product if an online influencer reviews it positively.’, and ‘I am more likely to like a brand if an online influencer reviews it positively.’. These questions are based on the existing

literature on influencers (Bognar et al., 2019; Casaló et al., 2018).

The dependent variables are circular selling, circular buying, and fashion purchase intent. Measuring circular selling asks about habits towards selling apparel and sustainability. A single item was used to measure circular selling on. The following question item, ‘I sell my old clothes

for environmental reasons.’, was taken from Cho, Gupta, and Kim, (2015). To ensure the reliability

of a study, it is more preferable to have multiple-item measures instead of a single-item measure (Marsh, Hau, Balla, & Grayson, 1998; Sarstedt & Wilczynski, 2009). However, lately researchers have been arguing for the possible use of single item constructs (Bergkvist & Rossiter, 2007; Diamantopoulos, Sarstedt, Fuchs, Wilczynski, & Kaiser, 2012). Additionally, several articles have used single item constructs to measure for example age (Johnstone & Lindh, 2018), and Riordan and Griffeth (1995), used a single-item construct to measure intention to turnover. Thus, while multiple-item constructs are preferred, single-item constructs are acceptable.

22 Furthermore, to measure circular buying, three question items were used. These were developed in collaboration with the research project group and based on the literature on circular economy and circular fashion (Koch & Domina, 1997; Cho et al., 2015). These question items are measuring the reuse of clothing, buying behavior of timeless fashion items, and the intention to wear clothes or shoes for a longer time; ‘I only buy fashion items that are timeless (i.e. not based

on seasonal trends)’, ‘I reuse clothing in order to make the most out of them.’, and ‘I don't mind wearing the same clothes or shoes for many years, as long as they look and feel fresh.’. These

question items represent a circular buying behavior. Finally, to measure fashion purchase intent, four question items were asked that cover the increasing number of purchases and the change in time, inspired by Anastasiadou, Lindh, and Vasse (2019), who got influenced by Beldad, Hegner, and Hoppen (2016), and Hausman and Siekpe (2009). These question items provide estimations of future purchasing of fashion products. Like ‘I believe I will buy more fashion products in the future

than I do now.’ and ‘I intend to keep buying fashion garments from the online retailers I buy from today.’. All question items were measured using a seven-point scale ranging from ‘Totally

Disagree’ to ‘Completely Agree’ and an eight option ‘Don’t know’ was added to this scale. This created an alternative option for the respondent so they would not be forced to answer question items. This was done for ethical reasons (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 27.). The full operationalization table can be found in Appendix D.

Data Analysis

The data was analyzed using the analytical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). The response rate was calculated and resulted in 72.21%. This response rate was calculated from the personal messages sent to potential participants. The posts on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram were not included in the calculation, due to the fact that it is hard to know how many

23 people were reached by the post. However, the personal messages sent through one of these platforms were included in the calculation.

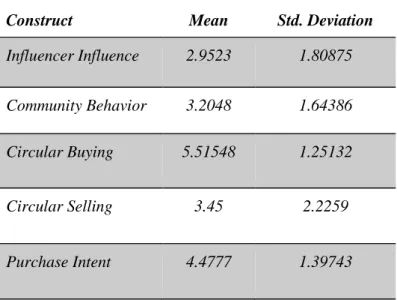

First, a Spearman rho test was carried out to see the correlations between question items in order to create the best possible constructs. Second, the internal consistency of the constructs was tested by using the Cronbach’s Alpha test (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 86). Consequently, the question items were compounded into the different independent and dependent variables. A Spearman rho was accomplished to measure if the variables were actually related to each other (Bell et al., 2019, p. 324-325). This test was chosen because a Spearman correlation coefficient is used when two variables are both measured on an ordinal scale (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 204). The Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient ranges from -1 to +1, where a negative sign indicates a negative correlation between the variables (Hinton, Brownlow, McMurray, & Cozens, 2014, p. 303). The five constructs created were community behavior, influencer influence, circular buying, circular selling, and fashion purchase intent. The descriptive statistics for these variables can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Constructs

Construct Mean Std. Deviation

Influencer Influence 2.9523 1.80875

Community Behavior 3.2048 1.64386 Circular Buying 5.51548 1.25132

Circular Selling 3.45 2.2259

24 To test the hypotheses, linear regression tests were performed. A linear regression test is used to describe the relationship between the dependent and the independent variable (Schneider, Hommel, & Blettner, 2010). Linear regression was used to better understand the relationship between the variables (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 210). With a linear regression, a single independent variable is used to predict the value of the dependent variable (Hinton et al., 2014, p. 313-317). The examination of the relationships between the independent and dependent variables is achieved by means of t-values (Lindh & Lisichkova, 2017). The general guideline is that a t-value should be equal or greater than the absolute value of two (Silvia et al., 2014, p. 116). Apart from a linear regression, three multi-linear regressions were performed to assess the strength of the relationship between two independent variables and one dependent variable (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 547). A multi-linear regression is usually performed when there are two or more independent variables predicting the value of one dependent variable (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 547-551). Moreover, a multi-linear regression was chosen to see if the results would be different compared to the results of the executed linear regressions.

Validity and Reliability

Validity of the question items was ensured by using already established question items used in other studies as much as possible, which is also known as face validity (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 86). Some items had to be slightly altered in order to fit our research topic of slow fashion, which may have decreased the validity of those question items. Moreover, the p-value was used to test the statistical significance between the dependent and independent variables. The p-value should always be less than 0.05 but preferably even lower (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 537). A p-value lower than 0.05 signifies that the relationship is statistically significant and that the results did not occur due to chance (Saunders et al., 2016, p. 537). Additionally, the linear regression test performed a t-value test. The t-value test also tests the statistical significance of the relationship between the

25 variables. In this case it validates whether the independent variable is associated with the dependent variable.

To ensure the reliability of the research, all the question items used an ordinal scale to avoid confusion for the respondents. Spearman’s Rho was used to test the correlations between question items to create constructs. All of these correlations can be found in Appendix E. The question items were then grouped into constructs and were tested by a Cronbach’s Alpha test to see how closely the question items are related to each other. Cronbach's Alpha tests the internal consistency of a construct (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 86). The Cronbach’s Alpha ranges from 0 to 1, where a low correlation between items indicates low reliability between the question items (Ghauri et al., 2020, p. 245). There is still a debate among researchers on what Cronbach’s Alpha score is preferable for a measure to be reliable (Hinton et al., 2014, p. 357). According to Hinton et al., (2014, p. 364), a score from 0.50 to 0.70 indicates a moderate reliability and a score from 0.70 to 0.90 shows a high reliability, and everything above 0.90 indicates an excellent reliability. The variables Community Behavior, Influencer Influence, and Fashion Purchase Intent were examined with a reliability test, and all variables showed a Cronbach’s Alpha higher than 0.70, indicating high reliability. Therefore, these constructs all had an acceptable internal reliability level (Hinton et al., 2014, p 357). The variable Circular Buying showed a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.536, which indicates a moderate reliability level. The construct Circular Selling was not tested because it is a single-item variable. All of the Cronbach’s Alpha values can be found in Table 2.

26

Table 2.Cronbach’s Alpha of Constructs

Reliability Statistics

Cronbach's Alpha N of Items Community Behavior 0.749 2

Influencer Influence 0.918 2

Circular Buying 0.536 3

27 Results

Correlations

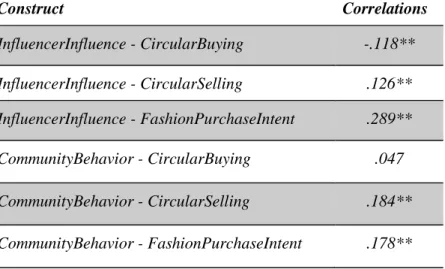

The Spearman’s rho test was used to check the correlations between the constructs. All correlations were found to be significant at the 0.01 level except for the relationship between community behavior and circular buying. This implies that all the other constructs show a relationship and the results are statistically significant and valid. The relationship between influencer influence and circular buying is -.118** indicating a negative relationship. Between influencer influence and circular selling the coefficient is .126** which shows a positive relationship. When it comes to influencer influence and fashion purchase intent, the relationship is .289** which shows that it is a positive correlation. For the dependent variable community behavior, its relationship with circular buying was insignificant. This means that there is no, or a very weak, relationship between the two constructs. For community behavior and circular selling the correlation coefficient r is .184**, showcasing a positive relationship. For the last constructs. community behavior and fashion purchase intent the coefficient was .178** which also implies a positive relationship. All the Spearman’s rho correlations can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Spearman’s Rho Correlations for Linear Regression

Construct Correlations InfluencerInfluence - CircularBuying -.118** InfluencerInfluence - CircularSelling .126** InfluencerInfluence - FashionPurchaseIntent .289** CommunityBehavior - CircularBuying .047 CommunityBehavior - CircularSelling .184** CommunityBehavior - FashionPurchaseIntent .178** **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

28

Linear Regression

To test the hypotheses a linear regression test was run using SPSS. Five out of six hypotheses were confirmed when using the linear regression test. For hypothesis H1a, community behavior

has a negative effect on circular buying, the hypothesis received a low t-value and a high

significance score indicating that there is no relationship present. Therefore, H1a was rejected. H1b, influencer influence has a negative effect on circular buying, was found to be supported. The regression received a t-value of -3.092 which is over the desired number of an absolute value of 2 and a significance level of .002. The correlation showed a negative effect from influencer influence indicating that the more influence an influencer has, less circular buying occurs. Thus, hypothesis H1b is supported. Further, hypothesis H2a, community behavior has a positive effect on circular

selling, was found to have a t-value of 4.812 and a significance level of .000. Additionally, the

correlation was positive thus indicating that community behavior has a positive effect on circular selling. Therefore, H2a was supported. H2b, influencer influence has a positive effect on circular

selling, was also supported. The t-value was 2.925, the significance was .004, and the correlation

was positive which all contributed to the confirmation of the hypothesis. Lastly, H3a, community

behavior has a positive effect on fashion purchase intent, and H3b, influencer influence has a positive effect on fashion purchase intent, were both found to be supported. H3a and H3b were

found to have a significance level of .000 and t-values of 4.812 and 7.283 respectively. They both had positive correlations, thus supporting both hypotheses presented. All regression results are summarized in Table 4.

29

Table 4. Linear Regression Results

Hypothesis Construct t-value Significance Beta B Supported

H1a CommunityBehavior - CircularBuying 1.571 .117 .060 .046 No H1b InfluencerInfluence - CircularBuying -3.092 .002 -.118 -.081 Yes H2a CommunityBehavior - CircularSelling 4.812 .000 .181 .249 Yes H2b InfluencerInfluence - CircularSelling 2.925 .004 .111 .139 Yes H3a CommunityBehavior - FashionPurchaseIntent 4.812 .000 .173 .149 Yes H3b InfluencerInfluence - FashionPurchaseIntent 7.283 .000 .287 .222 Yes

The implications of these results are that the independent variable of influencer influence is effective in affecting all the dependent variables while community behavior was not able to affect circular buying. The negative effect that influencer influence has on circular buying implies that their influence does not make consumers buy second hand items. However, the positive effect that influencer influence has on circular selling indicates that they can generate a more sustainable behavior through consumers recycling or reusing clothing items purchased. The results showed that community behavior also had a positive effect on circular selling, which further indicates that our peers have the possibility to influence consumers to donate used clothing. Lastly, both community behavior and influencer influence showed an expected positive relationship with fashion purchase intent. This implies that both influencers and the community surrounding them can persuade consumers to purchase fashion online.

30

Multi-linear Regression

When running the multi-linear regression, the results became quite different from the results when running the linear regression. Only three out of six hypotheses were confirmed. H1a was still rejected, however for a different reason. With a t-value of 3.307 and a significance of .000 the relationship was found to be significant. However, the relationship was found to be positive with a Beta of .142, therefore H1a was rejected. For H1b, there was no significant difference and the hypothesis was still supported. The t-value was -4.336 and the significance score was .000, with a Beta coefficient of -.186 thus confirming H1b. Furthermore, H2a was found to be supported while H2b was found to have a non-significant relationship. H2a and H2b had a t-value of 3.953 and 0.890 respectively, with H2a having a significance of .000 and H2b having a significance of .374. H2a had a Beta coefficient of .169, thus confirming the positive relationship that was hypothesized. Lastly, H3a was rejected due to insignificance while H3b was supported. H3a had the low t-value of 1.033 and the high significance score of .302, which leads to the rejection of the hypothesis. H3b received a t-value of 5.934 and a significance score of .000, with a positive Beta coefficient of .268. This leads to the confirmation of hypothesis H3b. All multi-linear regressions results can be found summarized in Table 5.

31

Table 5. Multi-linear regression

Hypothesis Construct t-value Significance Beta B Supported

H1a CommunityBehavior - CircularBuying 3.307 .001 .142 .109 No H1b InfluencerInfluence - CircularBuying -4.336 .000 -.186 -.129 Yes H2a CommunityBehavior - CircularSelling 3.953 .000 .169 .234 Yes H2b InfluencerInfluence - CircularSelling 0.890 .374 .038 .048 No H3a CommunityBehavior - FashionPurchaseIntent 1.033 .302 .047 .040 No H3b InfluencerInfluence - FashionPurchaseIntent 5.934 .000 .268 .207 Yes

The results from the multi-linear regressions show that there is a positive relation between community behavior and circular buying, whereas influencer influence has a negative effect on circular buying. This implies that while the influence of an influencer cannot make us buy more circularly, the communities surrounding them can. Moreover, the results show a non-significant relationship between influencer influence and circular selling, which implies that the influence of influencer would not have an effect on consumers selling their used clothes. However, the results show that community behavior has a positive effect on circular selling. This indicates that a community could make a consumer sell used clothing. Lastly, the results show no significant relationship between community behavior and fashion purchase intent, but a significant positive relationship between influencer influence and fashion purchase intent. The implications of this is that while an influencer can persuade consumers to purchase fashion, the communities surrounding them are not enough to encourage purchases.

The implication of the difference between the two tests, linear regression and multilinear regression, is that even though the behavior between two concepts was tested (see the confirmed

32 hypotheses in the first test) and supported, they may not be supported when put into context with other concepts. This case concerns the effect of Influencer Influence on Circular Selling (H2b) and Community Behavior on Fashion Purchase Intent (H3a), with them not being significant when put into context with the other. This indicates that these are not behaviors related to each other, i.e. they may concern different people or have different causes and should be tested in separate models, or investigated separately.

33 Discussion

Influencers are commonly used to promote brands and products (Ki & Kim, 2019). Previous studies have shown that influencers have an impact on consumer behavior (Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, 2019). Moreover, companies are increasingly using online influencers as part of their marketing strategy (Lou & Yuan, 2019). The findings of this study showed a positive relationship between the influence of influencers and purchase intent, as suggested by prior literature (Bognar et al., 2019; Ki & Kim, 2019), thus confirming H3b. This result was confirmed both when investigating the variable alone and in combination with community behavior. However, when comparing the influence of influencers and the influence of experts on purchase intent, Lindh and Lisichkova (2017) found that the impact on consumer purchase intent is not only explained by the influence of influencers. Consumers also seek information from experts in their decision-making process. Besides experts, previous studies showed that online communities have an effect on consumers’ perception of a brand or product and their attitude towards a brand or product (Wang et al., 2019), which subsequently could lead to higher purchase intent. A positive attitude towards a brand or product increases the purchase intent (Tiruwa et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). This is in line with the findings of this study, that confirmed H3a when using linear regression, and showed that community behavior has a positive effect on fashion purchase intent. However, H3a was not confirmed in combination with influencer influence, due to the non-significant relationship. This could be due to the fact that different researchers think that the relationship is affected by consumers’ willingness to participate in the community (Langaro et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2015).

Besides influencers, there are different social media platforms that created different communities (Wolny & Mueller, 2013). These platforms are commonly used to share information and experiences (Park et al., 2014), where the community affects consumers’ behavior (Alalwan et al., 2017; Park & Cho, 2012). These communities usually exist of people who share the same

34 values. Therefore, these communities might have the possibility to stimulate a more circular behavior when it comes to the use of fashion products. In the fashion industry, not only consumers but also companies are demanding a more sustainable environment. This has led to companies creating more sustainable clothing (Ritch, 2015). However, as Kirchherr et al., (2017) pointed out, practitioners often decided to leave out the ‘reduce’ part out of their definitions of circular economy, while academics included it. Reducing is important in both circular economy (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Kirchherr et al., 2017) and the slow fashion movement (Fletcher, 2007). However, some companies are persuading consumers to buy less. For instance, the well-known company Patagonia has implemented an influencer marketing strategy that emphasizes more sustainable practices and especially prolonging the life-cycle of their products (Bianchi, 2020). The findings show that both community behavior and influencers have a positive effect on circular selling. Both H2a and H2b were supported in the linear regression, and are in line with previous research. Therefore, communities and influencers could potentially help to stimulate a more circular behavior when it comes to the divestment of clothing. However, when combining the two concepts, only community behavior had a significant effect on circular selling, thus only confirming H2a. Nevertheless, these results show that there is a possibility that this could lead to a shift away from the take-make-waste model currently used in the fashion industry (Koszewska, 2018), and is also in line with what the slow fashion movement stands for as it is related to the reuse and recycling of apparel (Fletcher, 2007). Moreover, reusing and recycling clothes increases the lifecycle of fashion products (Lang & Zhang, 2019).

While it has previously been investigated how influencers affect purchase intent (Ki & Kim, 2019; Lindh & Lisichkova, 2017), no research to our knowledge has investigated the possible effects of how influencers affect more sustainable consumption patterns. In accordance with previous research, we found that influencers have a positive effect on fashion purchase intent (Ki