#AloneTogether

An exploration of social connectedness through

communication technology during physical distancing

Marsali Miller

Interaction Design

Master’s Programme (120 credits) Thesis Project One - 15 credits Spring 2020

Abstract

This thesis project explores how communication technology can foster the sense of togetherness to maintain the feeling of social connectedness during physical distancing. The current global pandemic COVID-19 is causing billions of people across the world to live in isolation or by physical distancing regulations. The elimination of almost all in-person interactions is affecting people’s mental health and has resulted in many people turning to communication technology to feel a sense of social connectedness.

The project builds upon three main areas of theory: the social and mental effects of physical distancing, designing for crises and design theories about togetherness within communication technology. The design process is guided by a research through design methodological approach, with the aim find out how people who are living in isolation and by physical distancing regulations are using existing forms of communication technology to feel a sense of social connectedness with others and what they need from it. The project addresses two key problematic areas which were identified during the fieldwork and literature review and are explored through prototypes. The prototypes focus on how to create a hang out feeling within online group interactions and how to create the in-the-moment feeling during shared online live experiences.

The outcome of this project includes in a problem framing, design process knowledge, research insights and prototypes that explore how to foster the sense of togetherness within communication technology. The findings from this project intend to contribute knowledge to the research and design community on how to design new or alternative forms of

communication technology that foster social connectedness during physical distancing.

Key words

Communication Technology; Research Through Design; Togetherness; Social Connectedness; Physical Distancing; Designing for Crises; COVID-19; Pandemic

Contents

1.

Introduction ... 6

2.

Background Theory ... 8

2.1 COVID-19: physical distancing ... 8

2.2 Designing for crises ... 9

2.3 Communication technology: loneliness and togetherness ... 11

3.

Canonical Examples ... 13

3.1 Goodnight Zoom ... 13

3.2 Netflix Party ... 14

3.3 Houseparty ... 14

3.4 Messenger Rooms ... 15

3.5 Everybody Headspace ... 16

4.

Methods ... 18

4.1 Literature review ... 18

4.2 Participatory observation ... 18

4.3 Interviews ... 18

4.4 Cultural probes ... 19

4.5 Affinity Diagramming ... 19

4.6 Sketching ... 19

4.7 Prototyping ... 19

4.7 Retrospective Think-aloud Protocol ... 20

5. Design Process ... 21

5.1 Research through design ... 21

5.2 Design process structure ... 21

5.3 Background study ... 22

5.4 Fieldwork ... 22

5.4.1 Participatory observation ... 23

5.4.2 Interviews ... 23

... 24

5.4.2 Cultural Probe Toolkit ... 24

5.5 Preliminary analysis and results ... 29

5.5 Ideation ... 32

5.6 Prototyping ... 35

6. Analysis and Main Results ... 40

7. Discussion and Reflection ... 45

8. Conclusion ... 48

9. Acknowledgments ... 49

10. References ... 50

1. Introduction

The world is currently experiencing the global pandemic COVID-19. Billions of people across the world are living in isolation or by physical distancing regulations. This has resulted in many people turning to communication technology to feel a sense of social connectedness and to replicate as much of their lives online as possible – social life, fitness, work, studies, entertainment and religion. This is affecting people’s mental health and eliminating almost all in-person interactions and could trigger a social recession – “a fraying of social bonds that further unravel the longer we go without human interaction” (Murthy & Chen, 2020). This massive interruption to the way we live is giving people space to pause and reflect on how we use communication technology and what we need from it now, during a crisis, and in the future. It is a time for creativity and experimenting, to find new and inventive ways to get through physical distancing and isolation together (Parker, 2020).

This project aims to use a research through design (RtD) methodological approach to find out how people who are living in isolation and by physical distancing regulations during the COVID-19 outbreak are using existing communication technology to feel a sense of social connectedness with others. RtD is an approach that employs methods and processes from design practice as a method of inquiry (Zimmerman, Stolterman, & Forlizzi, 2010). This approach uses methods and design artefacts to generate knowledge contributions, such as design theory, conceptual frameworks and guiding philosophies, for researchers and designers to build upon in future works (Zimmerman, Stolterman, & Forlizzi). The focus of this project is to explore what people need from communication technology during

physical distancing by identifying the current short comings and what is important to foster the feeling of togetherness online. The findings from this project will contribute knowledge to the research and design community on how to design new or alternative forms of

communication technology that foster social connectedness during physical distancing. Although crises are temporary, it is necessary to design for these times of heightened emotional stress and physical distancing. There are existing online platforms and services that offer the essential support needed at the time of a crises, such as food and shelter. These address the physiological and safety needs according of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the first two tiers of the five-tier model (Maslow, 1943) and address the subsistence need from Max-Neef’s Human Scale Development model – a more fluid and interrelated model of human needs. However, there is a need for tools that address the emotional needs during times of crises, such as togetherness and social connectedness, addressing the third tier of Maslow’s Hierarchy, love and belonging, and affection from Max-Neef’s model. To the best of my knowledge, there are less studies in this area. Therefore, this project intends to contribute to emotional needs by building upon existing theories of designing for social presence within interaction design, the impact of physical distancing and designing for crises.

Research question

How can existing communication technology foster a sense of togetherness to maintain the feeling of social connectedness during physical distancing?

In this project, ‘togetherness’ is defined as the feeling of being close to another person or people emotionally and the ‘hang out feeling’ is defined as the sense of social presence online that allows people to feel like they are hanging out together in-person. Key findings from the fieldwork about online group interactions and shared live online experiences lead to the formulation of two sub research questions. The sub research questions give a focused approach to the main research question by identifying two main problematic areas to explore with RtD prototypes. The key findings and problematic areas from the fieldwork will be described extensively both in the Design Process chapter and the Analysis and Main Results chapter.

RQ 2: How can interaction design features within online communication platforms create

the hang out feeling in group communication?

RQ 3: How can interaction design features within online communication create the

2. Background Theory

This chapter describes the context in which this project is based and background theory that I have built upon throughout the process. First, I will outline the different types of physical distancing regulations that billions of people around the world are experiencing and the mental health implications. Next, I will look at designing for crises within the field of interaction design, followed by theories about loneliness and togetherness within communication technology.

2.1 COVID-19: physical distancing

To prevent the in-person spread of COVID-19 governments are using a range of physical distancing methods, as recommended by the World Health Organisation, such as isolation, quarantine, physical distancing and cordon sanitaire (closed borders). As a result of this, large numbers of people around the world are living in isolation and more people than ever before are experiencing feelings of loneliness (World Economic Forum, 2020).

Isolation

Isolation is the separation of ill or infected people from others to prevent the spread of infection (World Health Organization, 2020). This method is for people who experience symptoms or are diagnosed with COVID-19 and can result in people isolating for up to 14 days.

Quarantine

Quarantine is the separation of people who are not ill but who may have been exposed to an infectious disease (World Health Organization, 2020). This method is for people who have either been in contact with someone who is known to be infected or has been traveling from an area that is known to have a high infection rate. This can result in people quarantining for up to 14 days.

Physical distancing

Physical distancing affects everyone. It requires people to keep a physical distance of two metres from other each other when in public spaces (GOV.UK, 2020). This is to reduce in-person interactions in the community and, therefore, the risk of spreading the disease from people who are pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic. However, physical distancing does not only affect the physical distance between people, it results in business closures, disrupts people’s livelihoods and separates families. Physical distancing has led to the closure of shops, schools, universities, office buildings, gyms, restaurants as well as the cancelation of gatherings and cultural events across the world.

Although the term ‘social distancing’ has become more common in the news, the term physical distancing the recommended by the World Health Organisation. Dr Maria Van Kerkhove argues that physical distancing does not mean that people have to socially disconnect from loved ones as technology allows people to keep connected in many ways without physically being in the same space (World Health Organisation, 2020). Kerkhove highlights that mental health is just as important as physical health during the COVID-19

Cordon sanitaire

Cordon sanitaire dates back to the 14th century to prevent the spread of plagues and has

been used since to prevent the spread of contagious diseases. More recently, it was

implemented as an effective measure during the SARS epidemic in 2003. It is the restriction of people entering or leaving an area that is infected to prevent spreading the disease. During the current outbreak of COVID-19 many countries have closed their borders to both non-citizens and countries with a high infection rates of the disease.

Research from previous global health pandemics show that public safety measures such as physical distancing and quarantine often have significant psychological impacts in the community. Studies suggest it can lead to increased rates of depression, anxiety, stress, fear and the feeling of isolation from the rest of the world (Brooks et al., 2020), (Douglas,

Harrigan, Douglas & Douglas, 2009). Common world-wide reactions to the outbreak of COVID-19 include stress and anxiety about the health of loved ones, personal health (especially for the risk groups), the disruption of access to regular medical care, loss of income, pre-existing mental health issues and stigma of the perceived risk of spreading the disease, for example, age, race, ethnicity, disability (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Researchers suggest that short periods of isolation can cause increased anxiety and depression within days (Murthy & Chen, 2020). Further, the COVID-19

pandemic could have long lasting effects on the social infrastructure of people’s lives and communities in the form of a social recession – “a fraying of social bonds that further unravel the longer we go without human interaction.” (Murthy & Chen, 2020). The impacts of physical distancing build upon the pre-existing and growing problem of loneliness within the modern world.

2.2 Designing for crises

Although crises are temporary, it is necessary to design for these times of emergency and heightened stress to be prepared for crises that may arise in the future. Crises cause both cognitive impairment and emotional stress, as nearly all of people’s cognitive resources are consumed. Designing for crises exists in fields such as architecture and interiors where the worst-case scenario is built into the infrastructure of the design, for example, fire escapes. More recently, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Avio Interios, an Italian design studio and manufacturer of airline seats, presented a two new product concepts Glassafe and Janus Seat to tackle the issue of physical distancing in airplanes (Avio Interiors, 2020). However, to the best of my knowledge, there is less in terms of designing for crisis within the field of interaction design. There are existing online platforms designed specifically for the response to crises such as conflict and natural disaster. Ushahidi is an online platform that was developed in 2008 to map reports of violence in Kenya after the post-election violence (Ushahidi, 2017). Since then, it has been used in response to crises including the Syrian conflict and earthquakes in Nepal. However, these existing tools are often specific to both events and locations and independent from more commonly used applications rather than being integrated in existing and commonly used platforms. One exception is

Facebook’s Safety Check and Community Help. As people often quickly turn to social media after a crisis, Facebook released the Safety Check feature in 2014 that was inspired by people's use of social media to connect with friends and family after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. It allows users to quickly let their Facebook friends know that they are safe after a crisis in their area by marking their profile is safe. The tool has

developed over the years from a feature that only appeared after a natural disaster in the relevant area, to becoming a permanent feature on Facebook for a wider range of crises including natural disaster, man-made disaster and terror related. Most recently it has been developed into the Community Help feature with offers a wider range of services as it is a platform specifically, "to connect people who needed help with those who could offer help.” (Chethan, 2017). The feature is location based and allows people to offer and search for essentials including food, water, shelter, transportation and equipment. More recently, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been new features added to existing location-based platforms and new products designed to address the essential needs. Both Google Maps and Apple Maps have added features to their platforms that show COVID-19 testing sites in the United States of America (Peters, 2020). Further, Sidewalks Widths NYC is a new interactive map created by urban planner Meli Harvey that displays the widths of all of New York’s sidewalks and the ability of pedestrians to practice physical distancing (Sidewalk Widths NYC, 2020).

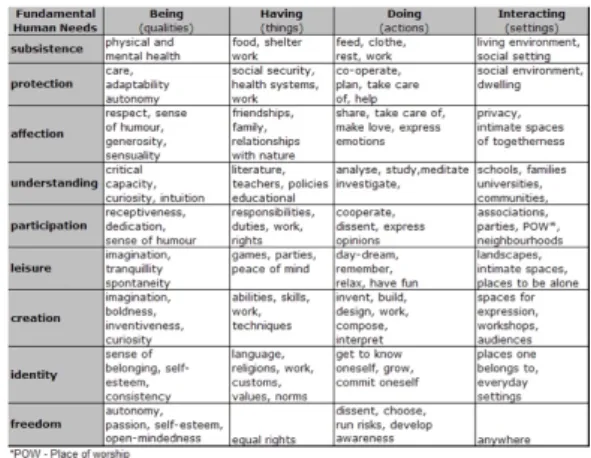

These existing tools address the essential needs in response to a crisis. According to

Maslow, they address the first two tiers of the Hierarchy of Needs - physiological and safety needs (Maslow, 1943) (Figure 1.). According to Max-Neef’s Human Scale Development model, an alternative and more fluid and interrelated model of needs to Maslow’s, these products address the subsistence need, which is the need for physical health that can be met with having food and shelter (Figure 2.). Maslow and Max-Neef’s models provide theoretical knowledge on human needs that can assist designers when designing for crises by focusing on needs such a food and shelter or emotional needs. However, there is also a need for tools that address the emotional needs during times of crises, such as togetherness and social connectedness, similar to the third tier of Maslow’s Hierarchy, love and

belonging, and the affection need from Max-Neef’s model which is met with friend and family relationships. To the best of my knowledge, there are less studies on this area, therefore this project intends to contribute in this area within interaction design by designing for emotional needs during physical distancing.

According to Huang et. al (2015), both physical and emotional proximity to a crisis should be considered when designing for emotional support and togetherness. In their study on the effects of proximity to a crisis on online information sharing behaviours, Huang et. Al found that emotional proximity emerged as a salient theme and did not always correlate with physical proximity.

Figure 1. Simply Psychology. (2020). Exploring Maslow’s Hierarchy of

They define emotional proximity as:

“A connection between a person and a disaster event. This connection can be mediated by an interpersonal connection, i.e. a close relationship with someone who is physically affected by a disaster, or through an experiential connection to the geographic location of the event.”.

Huang et. al suggest that people who feel emotional proximity to a crisis situation turn to social media to for both information about the crisis and to connect with those who are experiencing the crisis in-person. Communication technology has allowed people from across the world to respond to crises and come together online for help and information. However, there is a need for a greater sense of togetherness online at a time of emotional stress and physical distancing during a crisis.

2.3 Communication technology: loneliness and

togetherness

Loneliness was prevalent before the COVID-19 pandemic, with communication technology being a major factor in this. Ubiquitous computing has revolutionised the way people communicate by allowing their lives to become interwoven with technology resulting in a growing shift of human interaction from face-to-face to screen based. In Alone Together, MIT Professor Sherry Turkle argues that communication technology and social media networks are being advertised as bringing people together, however in reality they are making people lonelier than before. Turkle argues that family homes and communal spaces are no longer a place of social collection, as people are constantly tethered to their mobile devices they are living alone, together. Turkle’s theory is that in a world of constant digital communication people feel more alone than before. Ironically, during the COVID-19 pandemic, nine years after Alone Together was published, #alonetogether has become a trending hashtag on social media as people around the world living in isolation and physical distancing are turning to communication technology to be connected to one another (Koeze & Popper, 2020).

Within the field of communication technology, studies have been conducted to research how to design for the sense of social presence and closeness. In the project SynchroMate, Gibbs, Vetere, Bunyan and Howard (2005) explore preliminary ideas about phatic

technology, “technology designed to mediate intimacy by affording serendipitous

synchronous exchanges.". The project studied the role of interactive technologies within intimate relationships and how to design for phatic communication technology –

technology that sustains social interactions, rather than convey information, to maintain social connection. The key findings from this project are that ongoing connectedness or frequent exchanges were crucial to maintaining relationships with less importance placed on the informative value of the exchange (Gibbs, Vetere, Bunyan & Howard). Therefore, when creating the sense of social presence, communication technologies should offer phatic exchanges, which can be either peripheral or focused.

Gibbs, Vetere, Bunyan and Howard coined the term ‘phatic technology’ as they believe that when designing for social connection and relationships:

“It is crucial for designers to break away from the notion that communicative

exchanges must necessarily be about the conveyance of message, and informational context.”

The concept of phatic technology challenges interaction designers to:

“Find ways to support and encourage phatic exchanges alongside the forms of information exchanges supported by existing devices.” (Gibbs, Vetere, Bunyan & Howard).

Further, in the study The Impact of Social Presence on Feelings of Closeness in Personal Relationships, Gooch & Watts (2014) explore the two phenomenological concepts of social presence and closeness within communication technology and personal relationships. They define social presence as, “a short-term feeling that is only experienced during an act of communication,” which contributes and increases the feeling of closeness. Gooch & Watts argue that closeness is a longer-term concept and can be maintained regardless of the communication technologies that people use, therefore, researchers and designers should focus on creating technologies that foster the in-the-moment feeling of using technology and the sense of social presence.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a surge in popularity of live streaming on different digital platforms such as Instagram. Live streaming is a feature that has existed on platforms before COVID-19 that allows users to stream live videos to their followers and includes a comment section for viewers to communicate in real time. During the COVID-19 pandemic, while people around the world are isolating, Instagram Live has become a popular tool for streaming live music performances, Q&A sessions and fitness classes. During the pandemic DJ D-Nice’s physical distancing dance party live stream went viral with over 100,000 people viewing at one time, and triggered a trend in musicians, artists and nightclubs hosting live streamed music gigs and dance parties on Instagram Live. The significance of Instagram Live is that anyone can join at any time to experience the in-the-moment feeling of a live event at time where almost all large-scale events are cancelled. The real time display of how many people are watching the live stream and names of accounts as they join the audience allow people to feel part of a shared experience and community. During DJ D-Nice’s nine hour ‘Club Quarantine’ live stream, celebrities and politicians virtually attended, such as Michelle Obama, Drake, Oprah Winfrey and Mark Zuckerberg, sharing a moment with the rest of Instagram’s community.

Summary

Technology should not be a permanent substitute for in-person social connection and interaction, however, at a time where billions of people are living in isolation or physical distancing, it can offer a sense of togetherness. Physical distancing and isolation go against the human drive for social connection, therefore, now more than ever people need a sense of social connectedness. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people are turning to

communication technology to connect with one another and share experiences together by trying to replicate their social lives and interactions online. In response to the need of social connectedness online during the COVID-19 pandemic, communication technology platforms are adding new features to try and re-create the hang out feeling which are discussed the following chapter Canonical Examples.

3. Canonical Examples

The chapter includes forms of communication technology, and features within digital platforms, that are canonical examples of fostering a sense of togetherness online by creating the hang out feeling and the in-the-moment feeling. I will focus mostly on current examples that are being widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1 Goodnight Zoom

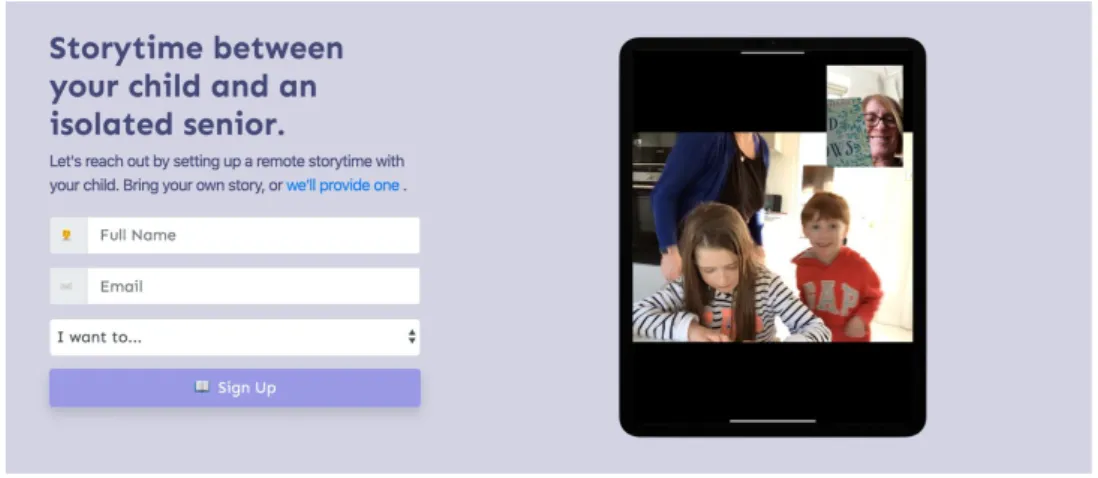

Goodnight Zoom 1 is a new product that was released in March 2020 in response to the

COVID-19 pandemic and trend in people using Zoom during this time (Figure 3.). It is an online service that pairs up young families with isolated seniors from nursing homes for a remote story time (Goodnight Zoom, 2020). The service uses the existing platform Zoom for the story reading sessions and provides access to children’s books online if they are

required. The product aims to foster the sense of togetherness and social connectedness by connecting young families with isolated seniors through a virtual story reading. Goodnight Zoom both recreates the in-person activity online and gives the online gathering meaning by addressing the issue of isolation causing loneliness among seniors.

Zoom Video Communications2, Inc. is a cloud-based video conferencing service. The

service has been available since 2013 though has experienced a surge in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Zoom was not designed to be a social network, however, it has become many people’s go-to communication tool during isolation for both social and professional meetings. In addition to Goodnight Zoom, users have been experimenting with Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic by adapting it to fit their needs to replicate many areas of their lives – social life, work life, studies, entertainment and fitness, through online dance classes, lectures, birthday parties and virtual pubs. Although Zoom has become the most popular platform during the pandemic (Asthana et al., 2020) (Koeze & Popper, 2020), it is designed for formal conference meetings and it does not foster more spontaneous and relaxed interactions.

1

https://goodnightzoom.com/

2https://zoom.us/

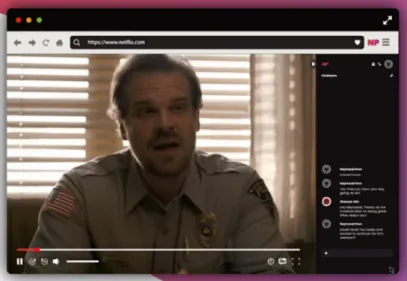

3.2 Netflix Party

Netflix Party 3 is a new extension available for the streaming platform Netflix which allows

groups of friends to remotely watch films and TV series alone, together online (Figure 4.). Users create a party group, decide what to watch and invite their friends using the URL for a virtual movie night. The main display is the synchronised video shared on all of the users’ screens, it also includes a chatroom feature on the right-hand side where users can send messages and share their reactions to what they are watching in real time. Groups are able to customise their Netflix Party by creating user icons and nicknames, uploading

screenshots, emojis and GIFs. Netflix Party is significant as it is one of the first mainstream online streaming platform extensions to attempt to create the hang out feeling for its users by hosting a virtual movie night. At a time where people around the world are isolating and physical distancing, Netflix Party allows groups of friends to feel a sense of togetherness online. Although users can share an experience by simultaneously streaming a movie together and communicating through messages, it is still far from the experience of being together in the same room. For example, as users cannot see or hear one another when using Netflix Party, they cannot see each other’s reactions or cannot experience

interactions, such as laughing together, that add the sense of social presence and to the experience of watching something together in-person.

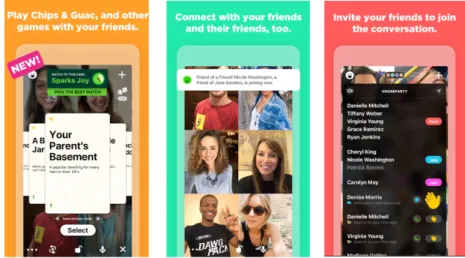

3.3 Houseparty

Houseparty 4 is one of the digital pioneers of creating the hang out feeling online as it

allows users to create virtual rooms for spontaneous video calls with their friends (Figure 5.). Unlike other video calling platforms, users do not need to call or invite other people. Users receive a notification when their friend opens the application and can instantly join video chats with them. This spontaneous way of interacting online in groups without scheduling meetings or sending invitations appeals to those who are looking for

alternatives to structured video calling platforms such as Zoom. According to Houseparty’s CEO Sima Sistani, it offers the “next best thing to hanging out in real life.” (Sistani, 2019).

3

https://www.netflixparty.com/

Further, during video calls, users can move between virtual rooms and play online games that are included in the application.

Houseparty was released in 2016 and initially received a lot of attention among young people and was installed by 35 million users (Singh, 2020). However, downloads of the application were declining until the COVID-19 pandemic. It experienced a surge in popularity with people across the world turning to communication technology to feel a sense of social connectedness. The company revealed that in March 2020 there were 50 million sign-ups, further it became the No.1 social application in 82 countries and No.1 in 16 countries (Perez, 2020). As one of the first platforms to attempt to create the hang out feeling online, Houseparty sparked a trend in communication technology platforms such as Facebook’s Rooms. However, Houseparty is limited in the sense that it is designed for a young tech-savvy audience and is only available on smartphones. This makes it far from ubiquitous and unsuitable for inter-generation communication, which is needed during the COVID-19 while billions of people from all ages groups and families are physical distancing from each other.

3.4 Messenger Rooms

Messenger Rooms 5 is a new feature on Facebook that focuses on what Facebook calls

“virtual presence” (Figure 6.). According to Facebook’s CEO Zuckerberg, the company is focusing on new products that help people stay connected and offer the sense of social presence – being able to feel like you are with a person when they cannot physically be there. The new feature Rooms allows users to create a virtual room and either invite specific friends and share an invitation link or allow any of their friends on Facebook to enter the virtual room at any time. The aim is to create the hang out feeling online rather than a scheduled meeting with a start and end time and formal invitations. Zuckerberg argues that this serendipitous approach allows for new kinds of interaction that technology did not offer before, further he argues that these kinds of interaction will remain in

demand after physical distancing regulations have eased (Newton, 2020).

5

https://www.messenger.com/rooms

The main concept of Rooms is that it allows for serendipitous interactions, however for this to occur users need to leave the virtual room unlocked to their Facebook connections. As the average user has hundreds of connections on Facebook and as anyone who has access to the virtual room link can enter, even if they are not connected to the host on Facebook or have a Facebook account, this allows for ‘roombombing’ - unwanted guests entering the virtual space and causing disruption. To prevent this, users can lock the room or only allow specific friends to enter, however, this safer option contradicts with the main concept that Zuckerberg promotes of serendipitous interactions as people cannot spontaneously ‘drop by’.

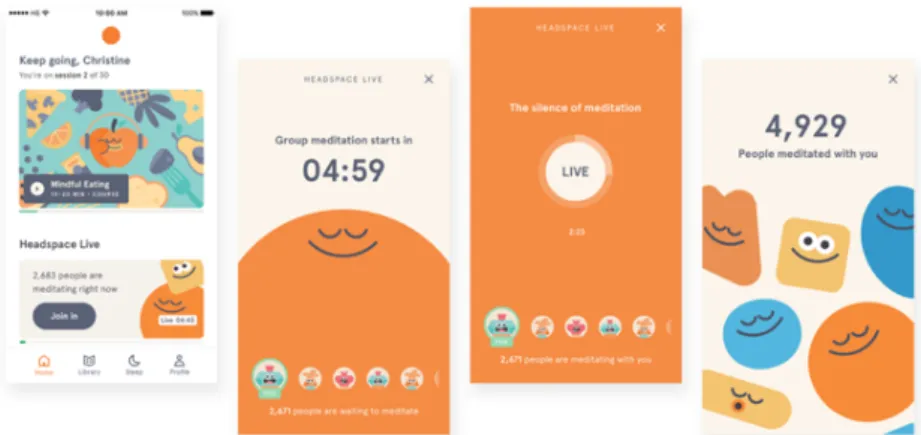

3.5 Everybody Headspace

Everybody Headspace 6 is a group meditation feature which was added in 2019 to the

Headspace application (Figure 7.). It allows users from across the world to join daily live meditation sessions. Users can see on the home screen of the application when the next group mediation will start, how many people are waiting to meditate together and have the option to join the virtual waiting room five minutes prior to the live session starting.

Everybody Headspaces provides minimal information about the participants as it simply displays how many other users are taking part in the group mediation in real time. This feature creates a sense of anticipation online which adds to the in-the-moment feeling. At the end of the live mediation session, the application displays how many people the user meditated with to further foster the sense of togetherness. Headspace hopes that this feature will, build a sense of community for people using the application (Headspace, 2019). The significance of Everybody Headspace is that it allows the Headspace community to be a part of a shared live experience with other people from across the world. It creates an in-the-moment feeling as users share their experience without communicating, but just by simply knowing that there are other people doing the same thing as them at the same time, together. Although this feature fosters the sense of togetherness and in-the-moment feeling, it does not foster the sense of social connectedness as the participants cannot interaction with one another.

Figure 6. Facebook Messenger Rooms. (2020). https://www.messenger.com/rooms

Summary

The platforms and features discussed in this chapter inspired this project as they are examples of how to foster a sense of togetherness online by creating a hang out feeling or in-the-moment feeling. This project builds up the concept of a virtual space for

spontaneous interactions and a virtual waiting room for shared online live experiences. Although these examples offer a range of ways to foster togetherness online, during the rush for almost all in-person interactions to be online during the COVID-19 pandemic, they are limited in terms of what people need which will be discussed extensively in the Analysis and Main Results chapter.

4. Methods

This chapter briefly describes the methods that I conducted during the project. The

following chapter Design Process will elaborate on how I applied these methods to research how communication technology can foster the sense of togetherness and social

connectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.1 Literature review

A literature review was conducted as an initial research method to explore relevant theories and to form the theoretical framework of the project. This also included exploring the design space in which the project intends to contribute to by researching relevant projects and canonical examples of products. The databases used for the literature review were ACM Digital Library, ResearchGate, MAU Library and Malmö University Electronic Publishing. This method was conducted to formulate the brief and gain an understanding of the topic area and previous studies that this project could build upon.

4.2 Participatory observation

Ethnography encompasses several qualitative and exploratory research methods which aim to deeply experience and understand the user’s world for design empathy and insight (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 60). Participatory observation is a form of ethnographic research and is both a data collection and an analytic tool that is used to gain a greater understanding of a phenomena from the participant’s point of view (DeWalt, 2010, p. 9, 19). Participatory observation is an ethnographic research method which involves the

researcher placing themselves into the participant’s context as a participating member of an activity to gain a first-hand experience while observing the group. This method allows the researcher to share the same experience with the other participants which provides in-depth insights and a greater sense of empathy. In comparison to auto-ethnography, participatory observation removes the formal structure of the research playing the observer role. However, by playing the role of the participant, there is the risk of the researcher influencing the other participants’ behaviour. This method was conducted to gain a greater understanding and insights into the experience of using communication technology to feel a sense of social connectedness during COVID-19.

4.3 Interviews

Interviews are a way to collect qualitative information about people’s personal experiences (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 102). Semi-structured interviews are part of ethnographic research which include a combination of closed and open-ended questions, often

accompanied by follow up questions. The dialogue can meander around the topics on the agenda, rather than a standardised survey, and may delve into unforeseen issues

(Newcomer, Hatry & Wholey, 2015). Semi-structured interviews were conducted to gain insights into people’s personal experiences of using communication technology during the COVID-19 pandemic as they are more conversational than structured interviews, this

were chosen as method over surveys as they allow for more in depth responses through open ended questions which can be tailored for the interviewee’s personal experiences during the interview.

4.4 Cultural probes

Cultural probes are a collection of interactive tools that are given to participants to use in their natural settings over period of time. This method is part of ethnographic research and is designed to elicit responses that can provide insight into people’s daily lives, thoughts and values (Boucher et al., 2018), (Gaver, Dunne & Pacenti 1999). The aim of this method is to collect “inspirational data” and stimulate imagination (Gaver, Dunne & Pacenti 1999). According to Boucher et al. (2018), cultural probe tasks are designed to be simple and easy for participants to engage with and open to the participants’ interpretation. Cultural probes can include tasks that require quick responses as well as longer-term reflection, with an affective tone that ranges from relatively neutral to playful, making them enjoyable and potentially intimate. Cultural probes were chosen as a method for this project as it allows for insights into the participants daily life and experiences and can result in imaginative and unique outcomes. The participants were sent a cultural probe toolkit, a collection of cultural probe methods, which involved four tasks to provoke a range of responses. The tasks included a dairy task, the Love Letter and Breakup Letter task, a photograph task and a creative challenge called ‘Hack it’.

4.5 Affinity Diagramming

Affinity diagramming is an analysis method used to map observations and insights gathered from research methods by clustering them based on affinity. This method was conducted to synthesise the qualitative data gathered from the research methods and consider the significance of each insight before formulating general and overarching themes (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 12).

4.6 Sketching

Sketching is central to both design thinking and producing concepts. According to Buxton (2007), sketching is a process to explore ideas rather than convey defined ideas. Ssketches are quick and disposable and are the by-product of sketching (Buxton). This method was chosen as it is a quick way to explore ideas, identify problems in concepts and iterate with further sketching.

4.7 Prototyping

Prototyping is a method conducted to explore designs for interactive artefacts and to represent different states of an evolving design (Houde & Hill, 1997). Houde & Hill argue that, rather than producing the artefact’s identical attributes, designers should focus on addressing one of the fundamental questions about the interactive artefact being designed: What role will the artefact play in a user’s life? How should it look and feel? How should it be implemented? (Figure 8).

This method was conducted to test theories that were generated from the key fieldwork findings and insights. Prototypes are research tools within RtD which explore a problematic situation to generate knowledge. According to Zimmerman, Forlizzi & Evenson, the final output of a RtD methodological approach is a concrete problem framing and series of artefacts – models, prototypes, products and documentation of the design process (Zimmerman, Forlizzi & Evenson, 2007).

4.7 Retrospective Think-aloud Protocol

Think-aloud protocol is an observational method that involves participants to complete a task using a prototype and articulate what they are thinking, doing or feeling (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 180). This self-reporting method is used to evaluate a product and reveal aspects that of a product that delights, confuses and frustrates the user (Martin & Hanington). Retrospective think-aloud protocol involves the participant first completing the task using the prototype then retrospectively talking about their experience.

Retrospective think-aloud protocol was conducted in this project as the focus was on the evaluation of the concept as a whole, rather than a traditional usability test. This way of conducting the method allows the participants to reflect upon the experience and concept as whole rather than small details.

5. Design Process

This chapter describes the RtD methodological approach I conducted and structure of the design process. It describes how I applied each method during the design process to research how communication technology can foster the sense of togetherness and social connectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5.1 Research through design

The methodology in this project has been guided by a research through design (RtD)

approach. RtD is an approach that employs methods and processes from design practice as a method of inquiry (Zimmerman, Stolterman, & Forlizzi, 2010). RtD uses methods and design artefacts to generate knowledge contributions, such as design theory, conceptual frameworks and guiding philosophies, for researchers and designers to build upon in future works (Zimmerman, Stolterman, & Forlizzi). I chose to conduct a RtD approach for this project to explore the sense of togetherness experienced when using communication technology at a time of physical distancing to contribute knowledge for future works. This project integrates knowledge and theories from different disciplines and intends to

contribute theories for new forms and features within communication technology.

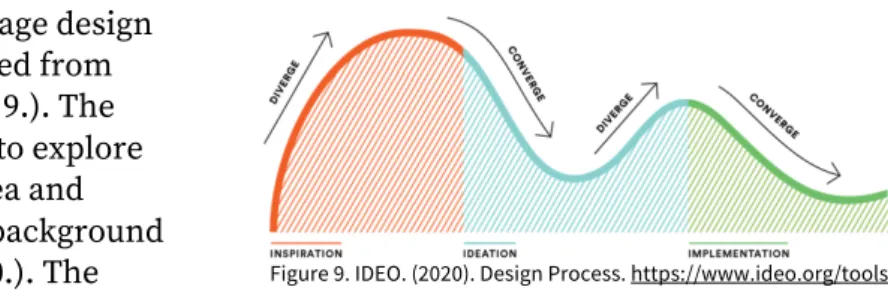

5.2 Design process structure

This project followed a four-stage design process which has been adapted from IDEO’s design process (Figure 9.). The first stage is a divergent stage to explore the context of the research area and gather data which involved a background study and fieldwork (Figure 10.). The

second stage is a convergent stage to analyse and synthetize data gathered from fieldwork. The third stage is a divergent stage to generate ideas and concepts from the analysis to test in the fourth stage. The final stage is a convergent stage, to test and analyse the concepts and produce theories addressing the research questions.

Figure 9. IDEO. (2020). Design Process. https://www.ideo.org/tools

5.3 Background study

An initial literature review was conducted at the beginning of the project explore relevant theories and to form the theoretical framework of the project. During this stage the brief for the project was still open for adjustments and focused on the topic of communication technology and togetherness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Once establishing a

theoretical framework, a review on relevant interaction design projects and canonical products was conducted to explore the design space in which the project intends to contribute to.

The databases used for the literature review were ACM Digital Library, ResearchGate, MAU Library and Malmö University Electronic Publishing. In addition, The Guardian podcasts, TED Talks videos and Dezeen’s ‘Daily coronavirus architecture and design briefing’ were also used to research communication technology during COVID-19 and designing for crises. The initial keyword search terms used were ‘togetherness’ and ‘communication technology’ to explore theories and design studies in this area. This was followed by ‘social isolation’, ‘loneliness’ to gain an understanding of how communication technology has both causes social isolation and tackles the issue of loneliness. To research theories and design studies conducted in the field of designing for crises, key words including, ‘crisis, ‘pandemic’ and ‘interaction design’ were used. Further, the literature review also included researching RtD methodology.

5.4 Fieldwork

The fieldwork consisted of participatory observation, interviews and cultural probes. This stage was conducted to gain an understanding and insights into how people were using communication technology to maintain the feeling of social connectedness during physical distancing. As aim of the study is focused on people living in isolation or physical

distancing, participants from Scotland, UK were chosen as they were living in ‘lockdown’ at the time of the project. There were 10 participants who took part in the study living in different locations in both cities and rural areas across Scotland. There were six females and four males, seven of the participants were in the age group 25 – 30, two participants were 30 – 40 and one was 65+ years old. A varied age range was chosen to gain insights into cross-generational communication. Participants from different locations within Scotland to gain a wider demographic and insights in to experiences of people living in different social contexts.

At the time of the fieldwork, the UK’s lockdown required all the participants to work or study from home (GOV.UK, 2020). Further, they were required to stay at home with the exception of going outside for one hour of exercise a day and shopping for essentials. Participants were only allowed to interact in-person with the people that they lived with and were only allowed outside in groups of up to two people while keeping a physical distance from others. At the time of the interviews and cultural probe toolkits, the lockdown regulations had been in place for five – seven weeks.

The participants were informed of the aim of the study and provided both written and verbal consent to take part in the study (Appendix 1 & 2). Participation in the study was voluntary and all of the research activities were optional.

5.4.1 Participatory observation

Participatory observation was conducted both to experience and observe how it feels to take part in group video call during physical distancing. I participated in two group video call with family members who were living in different households and by physical

distancing regulations (Figure 11.). The participant group was inter-generational and based across Scotland while I was living in Sweden. When the participatory observation was conducted, the participants had not interacted with each other in-person for five-plus weeks. The video calls were conducted on Zoom as this was the platform that the

participants were using to communicate with each other on a weekly basis during physical distancing to replace their in-person social gatherings. Participatory observation allowed me to observe how it feels to try to connect and hang out with family members remotely who were unable to see each other in person.

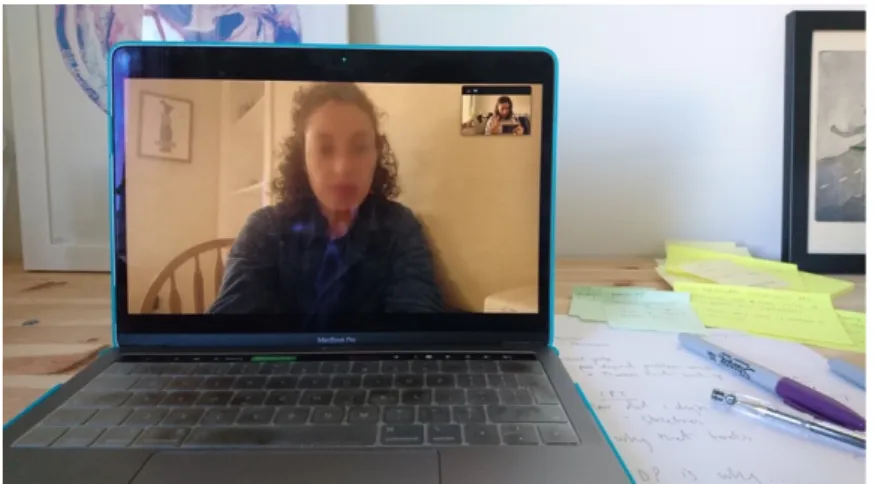

5.4.2 Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants to gain insights into their experiences of using communication technology during the COVID-19 pandemic to foster a sense of togetherness and maintain the feeling of social connectedness (Figure 12.). The interviews were conducted remotely due to the physical distancing circumstances. Zoom was chosen to conduct the interviews as it was the most common platform amongst the participants. The interviews were conducted after the cultural probes were sent to the participants and before they had been returned, so the participants were sensitised to the topic though had not provided any insights yet. As the interviews were semi-structured, they covered key topics rather than pre-determined questions, to allow flexibility for each interview to be adapted to the experiences of each interviewee (Appendix 3, 4 & 5). The main topics that guided the interviews included:

• The participant’s experiences of using communication technology to interact with people during

physical

distancing• The forms of communication technology that participants are using during

physical

distancing and different experiences of using them• The sense of social presence and togetherness when using different types of communication technology

5.4.2 Cultural Probe Toolkit

In addition to the interviews, a collection of cultural probe tasks were sent to participants via email with the intention to gain insights into the participant’s daily life and experiences using communication technology while physical distancing. The cultural probe toolkit included four tasks ranging from quick responses to longer-term reflection and was issued to the participants for two weeks. The playful and informal tone of the tasks aimed to be engaging and provoke imaginative and unique outcomes. The tasks were sent together as a toolkit along with an information letter (Appendix 6). Each task was sent as a Word

Document and included: a description of the task, the length of time required to complete the tasks and examples of possible outcomes.

The Diary

Participants were sent a diary template and asked to use it for seven days to write about their experiences of using communication technology (Figure 13.). The aim of the dairy was to find out the role communication technology played in their daily lives, how it fit into their routine and gain insights into their experiences of different types of interactions. The dairy included optional questions that encouraged both qualitative and quantitative

answers.

The questions in the diary included:

• What type of communication technology did you use? • Did you plan to use it with others? How did you schedule it? • How long did you use it for to interact with others?

• How close did you feel to the person / people you interacted with both before and after?

The participants were asked to return the diary document via email 14 days after receiving it, allowing them leeway when completing the task. This method allows for longer-term reflection on their behaviour and habits and for participants to express themselves freely in their own time and words. (Appendix 10).

The Love Letter & the Breakup Letter

The Love Letter and Breakup Letter is a playful method that intends to bring out people’s emotions about a product in a familiar format of a letter. The task is a personal letter written to a product which often reveals profound insights about what people value and expect from products (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 114). The participants were sent a template of both a love letter and a breakup letter and were asked to choose a form of communication technology that they had been using recently to keep in touch with others during physical distancing to write the letters to (Figure 14.). The participants were asked to focus on their experience of using the platform when interacting with other people. This method was conducted to gain insights into what delights and frustrates people about the experience of using a certain form of communication technology when interacting with others during physical distancing. (Appendix 11).

Take a Photo

The Take a Photo task was inspired by the common cultural probe task of giving

participants a disposable camera with instructions to take photographs of different aspects of their personal life to reveal insights about the participants (Gaver, Dunne & Pacenti 1999). Participants were asked to use their smartphone to take a photograph of their go-to place when using communication technology to interact with others (Figure 15.). This method was conducted to gain insights into how communication technology fits into their daily lives by providing a glimpse of their environment.

Hack it

The Hack it task was inspired by the way that people are adapting existing forms of

communication technology during the COVID-19 pandemic to replicate parts of their lives that would usually happen in-person, for example, virtual dance classes, virtual pubs and virtual music concerts. This task challenged the participants to reappropriate a form of communication technology using it for something new and write a brief description about their experience focusing on how it worked and what could have made the experience better (Figure 15.). This method was conducted to gain insights into what participants need from communication technology to socially connect during COVID-19 beyond their existing features and purposes. (Appendix 12).

5.5 Preliminary analysis and results

Affinity diagramming was used to analyse and synthesize the data gathered from fieldwork. This method was chosen as it allows for each unique insight to be considered before

generalising the data into overreaching themes. The interviews were analysed first, followed by each method within the cultural probe toolkit in order to both analyse the results and the methods themselves (Figure 16.). As each method was being analysed, interesting insights and quotations were gathered on post-it notes and roughly grouped in clusters of common themes (Figures 17 & 18). As there was a large amount of data to analyse, the process involved several iterations of clustering. Once all of the insights were gathered and clustered into groups, common themes emerged, such as issues with group video calls and participating in shared online live experiences. Key words were written on post-it notes and added to the groups. The key words included: group communication, simultaneous activities, social structure, dynamics, pressure, live experiences, closeness, peripheral and focused. The words were intentionally not specific to a communication technology platform in order to keep the process open and focused on concepts rather than specific platforms. Problem areas were formed for each group summarising the main issues from the insights and were written on larger post-it notes in a different colour and added to the clusters.

02 The Love Letter

& the Breakup Letter

Love LetterDear Zoom,

Thanks for being there for me during quarantine. I feel like we know each other so well now. You are more reliable and interesting than some of my human friends. Thank you for connecting me to yoga classes and friends around the world without having to sign up. You are so simple and straightforward. You are a millenials platform. You make my ex Skype look like a dusty old antique. You barely ever freeze. You let me see everybody’s faces in gallery view. You let me record hilarious family moments and you never ask me to input my personal details. You let me have more than 4 people in a chat (I’m looking at you Watsapp video grrrr) and we don’t all have to share the same type of email account (like you Microsoft Teams, you are so yesterday). You are so dreamy.

Yours always, Alannah

Breakup Letter Dear Zoom,

You ASSHOLE. I always loved Watsapp video way more than you anyway. Who needs you when I have Microsoft teams?! Apparently you’re not even that secure and you’re probably using all of my yoga moves and family gossip to manipulate me through advertising. TRAITOR. What’s with only letting one person speak at a time as well?! Have you ever heard Irish people have a conversation? If you don’t all talk over one another you clearly all hate each other. It’s evident that you were not created with the Irish in mind and for that, I can never forgive you. They are my people. Instead I will go forward and use several different more complicated platforms to replace you and shun you forever.

DON’T CALL ME. But watch me walk away. I wish it could have been different but Marsali said that it couldn’t.

Yours never, Alannah

The key results from the fieldwork lead to the formulation of the sub research questions. The research questions give a focused approach to the main research question by defining two areas to explore with RtD prototypes. The two areas that were chosen to focus on were group video calls, as this was the most common form of interaction amongst the

participants during physical distancing, and shared online live experiences, such as fitness classes, as seven of the participants mentioned regularly participating in these events

Figure 17. Affinity mapping

Findings from the affinity diagramming method suggest that group communication on video calls can feel forced and unnatural as only one person in the group can speak at a time in order to be heard. Participant E describes their experience of group video calling as, “a series of one-on-one conversations while everyone else waits their turn,". This can lead to uncomfortable silences as people do not know when to speak or wait for someone else to start speaking. This formal meeting style structure of interactions does not foster a feeling of hanging out as it does not allow for side conversations or for people to easily move between conversations which can be done during in-person group interactions. These findings lead to the development of the hypothesis that fluid and flexible interactions that allow for spontaneous conversations within group communication fosters a hang out feeling. To test the hypothesis a sub research question was formulated:

RQ 2: How can interaction design features within online communication platforms create

the hang out feeling in group communication?

Further, the findings suggest that when participating in shared online live experiences that would usually be in-person, for example yoga classes, fitness classes or exams, people can feel a sense of togetherness simply by doing the same thing at the same time as others. In the fieldwork interview participant A argues, “other people doing the same thing at the same time as you online is a form of connection with other humans.”. However, when there is not an opportunity to interact with others either before or after the activity, people can feel detached.

In the Diary task, participant A describes their experience of doing an exam online that would usually be done in-person:

“I video called a classmate after an online exam to see how she was. It’s strange doing exams without the familiar faces of your comrades who are in the same boat as you. It was nice to see another washed out face.”.

Further, participant A describes their experience of feeling togetherness while participating in an online yoga class:

“At the end of the class, the teacher unmutes the class for a meditation using mantra to feel more connected. Some people chant, some people mute themselves again, some people don’t chant. I chant. Afterwards, we say goodbye and everyone wishes each other good wishes for the day to come. It is one of the most genuine

interactions I have had online.”.

These findings lead to the development of the hypothesis that the opportunity to

communicate with other participants before or after shared live experience online fosters the in-the-moment feeling. To test the hypothesis a sub research question was formulated:

RQ 3: How can interaction design features within online communication create the

5.5 Ideation

The ideation process developed common themes from the affinity diagramming into sketches and concepts while considering background theory from the literature review. To explore ideas that address the sub research questions, two user scenarios were formulated and developed through a journey map (Figures 19 & 20.). The scenarios were: the user wants to hang out with their friends/ family spontaneously and the user wants to be a part of a shared online experience. The first scenario addresses research question two by focusing on fostering the hang out feeling and the latter addresses research question three by focusing on creating the in-the-moment feeling. The journey maps were quick sketches and explored a range of different possibilities for how new features within communication technology could allow people to hang out with friends and family online spontaneously and allow people to be a part of a shared online experience. The sketches mapped out the user’s journey would step-by-step and included different routes and options.

As Zoom was the most common platform for both group video calls and online live

experiences during physical distancing amongst the participants, the concepts were based on this platform. After establishing the two scenarios, the existing user journey on Zoom was mapped out step-by-step, for example, the process of a user setting up group video call on Zoom and the process of joining a live yoga class (Figure 21.). Problematic areas in the existing journey were identified, such as the cold and impersonal waiting room in Zoom that does not provide the user with any information on the other participants prior to joining the video call or allow for social interactions (Figure 22.).

Once identifying the areas that the concepts would focus on, another set of journey maps sketches were created to explore the specific stage in the existing journey that the

prototypes would focus on improving. The sketches mapped out each stage of the journey including the information provided to the user and the opportunities for interactions. For example, before entering the virtual waiting room the user can see how many other participants are in the waiting room and once entering the waiting room they have the option to interact with them with a message or video call (Figure 23.).

Figure 21. Journey map of Zoom existing features

Figure 22. Existing Zoom waiting room feature

Following the journey maps, the next stage of the process was to add a further layer of detail by quickly sketching wire frames of how the concept would work screen-by-screen. (Figure 24 & 25.). The wire frames helped both in making the ideas more concrete and lead to the next stage in the design process of prototyping.

Figure 24. Waiting room concept wire frame

5.6 Prototyping

Following ideation and sketching, the key concepts were transferred into interactive prototypes using the online prototyping tool Figma. The prototypes focus on the role they play in the users’ lives and what features are needed to support it (Houde & Hill, 1997). The purpose of the prototypes is to test the main concept and is not to be a fully functioning prototype or include definite details. The prototypes guide the users through one flow of interactions. According to Buxton (2007), the prototypes could be considered as a sketch as they are quick and only have sufficient fidelity to serve its intended purpose. The intend to explore the problematic areas and to generate knowledge for potential solutions.

Five of the participants from the fieldwork research took part in the prototyping testing. There were two males and three females, three of the participants were in the age group 25 – 30, one was 30 – 40 and one was 65+ years old. The participants were sent an information letter via email briefly explaining each of the concepts, the purpose of a role prototype and how to use Figma to interact with a prototype. Retrospective think-aloud protocol was used which allowed the participants to explore the prototypes independently without the

temptation to ask questions as this could have influenced their experience. After

completing the prototype, a semi-structured interview was conducted on Zoom (Figure 26.). As the interviews were semi-structured, there were main topics that guided the

conversation rather than pre-determined questions to allow for flexibility for the interviews to be adapted to the experiences of each interviewee (Appendix 13, 14 & 15).

The main topics included:

• Their experience of using the prototype step-by-step and any thoughts they had along the way

• How the concept compares to their experience of using Zoom or similar platforms • Changes they would make to the concept

• How they would adapt the concept for a different context than what was shown

5.6.1 Prototype one

Based on the findings in pages 30 - 31, and related to research question two — how can interaction design features within online communication platforms create the hang out feeling in group communication? — I developed the concept that fluid and flexible

interactions within group communication and the opportunity to give an identity a virtual space for communication can create a hang out feeling. Prototype one also builds upon background theory of making meaningful connections online. Priya Parker, author of ‘The Art of Gathering’, argues that giving online gatherings an identity allows for more meaning social connections online during the COVID-19 pandemic as it distinguishes how it is different from the others. This theory is backed up by findings from the Diary task, where participant F describes attending ‘a digital night in the “pub” with pals,’ on Zoom. They discussed how taking part in the virtual pub activity made them feel closer to the other people participating and that giving the online gathering the identity of ‘digital pub’ it made it, “so easy for us to have a drink and a laugh together again.”.

Prototype one aims to create a hang out feel while providing an identity to a virtual space for group video call with the intention to set the dynamics, for example to allow people to feel like they could be back in their family kitchen together (Figures 27 & 28.). To test this hypothesis, the prototype re-imagines the group video call feature on Zoom. The feature allows users to create a virtual space and give it any identity, for example, ‘Family Kitchen Table’. Users can invite contacts into the virtual space and also allow others to drop into the space. When in the virtual space, users can see who else is in the space and move between one-one-one video calls and group video calls within the larger group. This aims to allow conversations to flow and develop organically similar to the dynamic of sitting at a kitchen table. The aim of this prototype is to allow interactions to be more spontaneous and fluid without scheduled start and end times and by allowing people to ‘drop by’. By giving the space an identity, this feature aims to give the group communication a meaning, rather than just another video call, and set the dynamics of the group communication.

Zoom currently offers a breakout room feature within its settings, however similar to the rest of the platform, this feature is suited for conference style meetings with a formal structure. The host of the meeting is the only user who can create the rooms and who can assign people to different rooms. The other users are unable to choose which room they enter and are unable to move between the different rooms. Once the host has decided and set the rooms and participants, all users are automatically transferred from the main group call to the room at the same time and only the host can end the room sessions. In this feature the users do not have control and the interactions are not fluid or spontaneous.

Figure 27. Prototype one, Family Kitchen Table, journey flow

5.6.2 Prototype two

Based on the findings in pages 30 - 31, and related to research question three — how can interaction design features within online communication create the in-the-moment feeling when participating in shared online experiences? — I developed the concept that providing an opportunity for participants to interact with one another before a shared online live experience, similar to a waiting room in real life, would enhance the in-the-moment feeling and feeling of togetherness.

Prototype two features a virtual waiting room for people who are participating in an online shared activity (Figures 29 & 30.). The prototype is based on a yoga class on Zoom, however the concept could apply to other shared live experiences online. When logging onto the class, participants have the option to join the virtual waiting room before the class starts and are notified with how many other people are in the waiting room. When in the waiting room, users can see the other participants and have the option to interact with both the participants and the host through either a message board or video call feature. The opportunity to interact with others before a shared online activity aims to enhance the in-the-moment feeling and feeling of togetherness. The concept includes a countdown to the class starting and once the activity has been finished the users are notified with a message about how many people they shared the experience with to further foster the sense of togetherness, for example, “You shared this experience with 28 other yogis. Namaste.”. This concept inverts the existing waiting room feature that Zoom currently offers. When users are in the existing waiting room, they have no control over entering or leaving the waiting room and do not receive any information about the other users who are either in the waiting room or the meeting. Further, they cannot interact with the other users while in the waiting room. In this feature, only the host of the meeting can accept people from the waiting room into the video call. This feature does not give the user the opportunity for interaction with others or foster a sense of togetherness.

6. Analysis and Main Results

Social structureThe key results found that group video calls were the most popular form of communication among the participants during physical distancing to feel a sense of social connectedness. Zoom was the most commonly used platform while also being a new platform to all of the participants. The findings suggest that group video calls bring people together while providing a virtual space for users to try to recreate the hang out feeling that they would experience during in-person group interactions. Participant B talks about their experience of group video calls during the fieldwork interview, “I think people want to create the same dynamic as they did when they were hanging out together as a group.”. While group video calls were the most popular form of communication for social connectedness, a common problem from the findings was that group video calls can feel unnatural and forced for adult users. Reasons for this include that people do not always know when to speak as only one person can talk at a time, unlike in in-person group interactions, and that social cues such as body language are lost in video calls. However, key observations from both the participatory observation and fieldwork suggest that this is an age specific issue, as children can behave more naturally on video calls. During the participatory observation children (one – five-year olds) added a playful dynamic by putting on spontaneous dance shows, showing demonstrations of their favourite toys and reading to the group from their favourite children’s book (ironically, the book was about germs) (Figure 31).

Participant D described their experience of a group Zoom during the interview:

“It is less natural, it is okay for a business type meeting as they are relatively formal, there is an agreed subject matter, time and structure to it. But for a social thing, it is less relaxed than normal in-person interactions.”.

The formal structure of interactions on communication technology platforms like Zoom such as time limits, scheduled start times and formal invitations can feel unnatural for people who are using Zoom to socially connect. In group video calls only one person can talk at a time in order to be heard, as opposed to during in-person group conversations where people can have side conversations and pick up on social cues that allow a natural flow of conversation.