Akademin för hälsa, vård och välfärd

ETHICAL DILEMMAS IN COERCIVE

PSYCHIATRIC CARE IN SWEDEN

As experienced by frontline-workers in their work with adult patients

MATTHIAS RAUCH

Huvudområde: Social Work Nivå: Master

Högskolepoäng: 30

Program: Master’s Programme in Social

Work within Health and Social Welfare

Kursnamn: Thesis in social work Kurskod: SAA062

Handledare: Christian Kullberg Seminariedatum:2021-06-04 Betygsdatum: 2021-06-14

ABSTRACT

Background: The use of coercion is an essential part of psychiatry despite occurrence of harm

to patients and psychiatric staff. Contrasting to a global trend to reduce coercion, the number of coercive admissions and coercive treatment in Swedish psychiatry remains stable. Previous research identified frontline-workers to be especially likely to experience ethical dilemmas in their work with coerced patients. The literature identified for this study explored links between ethical judgement and the use of coercion. Research indicates that ethical dilemmas can lead to moral distress, inconsistency in practice and overuse of coercion. Ethical deliberations in contrast can mitigate moral distress and can decrease use of coercion without detrimental effects to frequency of violence or treatment outcome.

Research question: Which underlying conditions, context, values, power differences and

ethical frameworks are involved in the experience of an ethical dilemma in psychiatric care for coerced patients?

Data collection and analysis: Seven interviews with frontline-workers (nurses, caretakers)

from two different institutions were conducted. Data analysis utilized Siegfried Jägers dispositive analysis that is based on Foucault’s discourse theory.

Results: Participants describe ethical dilemmas as a reoccurring phenomenon that is part of

their daily work. The structural context from which they arise was described with naming impersonal and unchangeable factors such as legislation and hierarchy or a risk-avoidance paradigm. Diametrically dilemmas themselves were experienced within social interaction and characterised by personal values, emotions and empathy. The patient’s best, patient autonomy, the responsibility to provide care to people in need were identified as main values. Descriptions of ethical dilemmas were shaped by ambiguity, but the justification of coercion was presented with a high degree of certainty. The critical interpretation of these findings on the background of previous research led to suggestions of ethical deliberation as tool to detect, reflect upon and resolve ethical dilemmas with the aim to strengthen staff rights as well as patients’ rights, decrease coercion by abolishing arbitrariness of ethical reasoning. However, changes to dissolve sources of power differences would need changes of legislation and orga nization of psychiatry.

1

TABLE OF CONTENT

1 INTRODUCTION ... 3

1.1 Purpose and Research ... 4

2 BACKGROUND AND PREVIOUS RESEARCH ... 5

2.1 Coercive practices in Swedish psychiatry ... 6

2.1.1 Historical development of Swedish psychiatry ... 6

2.1.2 Current psychiatric care in Sweden... 7

2.1.3 Frequency of Coercive practices in Sweden ... 9

2.1.4 Frequency of Coercive practices in Europe ... 10

2.2 Previous research on coercion ... 10

2.2.1 Reduction of coercion ... 12

2.2.2 Coercion in psychiatric practice ... 13

2.3 Ethical conflicts in psychiatric practice... 14

2.4 Ethical Frameworks in psychiatric practice ... 17

2.4.1 Ethical principles ... 17

2.4.2 Conflicts of ethical principles ... 18

2.4.3 Disadvantage of principle-based ethics... 20

2.4.4 The Power, Knowledge and Language complex... 22

2.5 What was missing in regarded research? ... 24

3 THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE... 24

3.1 Philosophical perspective ... 24

3.2 Discourse theory... 26

3.2.1 Critical discourse analysis ... 29

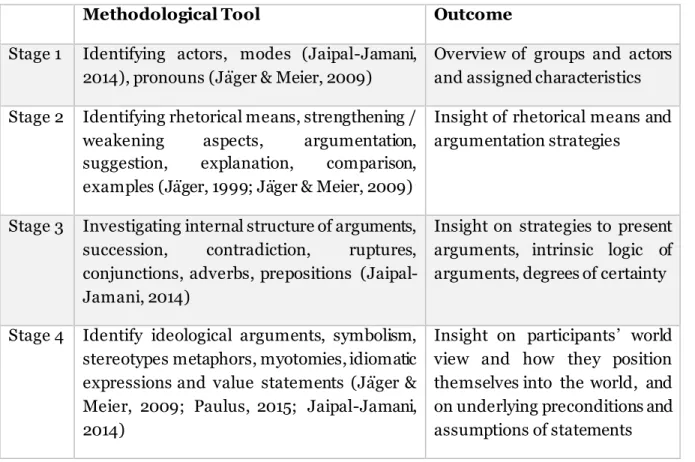

3.2.2 Dispositive Analysis ... 30 4 RESEARCH METHOD ... 31 4.1 Ethical Considerations ... 32 4.2 Data collection... 33 4.2.1 Sampling ... 33 4.2.2 Interviews ... 34

2 4.3 Data Analysis... 35 4.3.1 Material... 35 4.3.2 Process ... 36 4.3.3 First circle ... 36 4.3.4 Second cycle ... 39 5 RESULTS ... 40

5.1 Structural context of ethical dilemmas ... 40

5.2 Context of social actors ... 44

5.3 Use of discourse ... 51

5.3.1 Means to establish knowledge ... 51

5.3.2 Borders of discourse ... 53 5.3.3 Discourse Position ... 54 5.3.4 Power ... 55 6 DISCUSSION... 56 6.1 Discussion of findings ... 57 6.2 Methodological discussion... 64 7 CONCLUSION... 65 REFERENCES ... 67

APPENDIX A: INFORMATION ABOUT THE STUDY - SWEDISH APPENDIX B: INFORMED CONSENT - SWEDISH

APPENDIX C: PERSONAL GUIDE FOR INTERVIEWS – SWEDISH APPENDIX D: RESEARCH TRAIL

APPENDIX E: STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS TOPICS / SUBTOPICS

3

1

INTRODUCTION

The objective of health care is to improve and safeguard the health of the population and individuals. Health care shall be adapted to the needs and unique situation and the individual and their unique perception of health (Hälso- och sjukvårdslag, 2017:30). Within healthcare, the psychiatric field is portrayed as especially challenging and a focus of much debate and contestation (Eastman & Starling, 2006). The debate spans from complete rejection of psychiatry as a form of social control (Szasz, 1994) to the assumption that psychiatric treatment is essential to restore a person’s autonomy (Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2000). This disaccord might be especially drastic as the very foundation of psychiatric practice, namely the medical model of mental illness, the diagnostic process (Davis, 2010) and the efficiency of used treatments, are highly contested (Eastman & Starling, 2006). Consequentially, psychiatry is a medical field with extraordinary disagreement amongst professionals and inconsistency in treatment (Steinert et al., 2001). Treating individuals who are assessed to be incapable to make informed decisions poses an additional challenge.

Frequently encountered examples are persons in psychotic states that renders them unable to make informed judgements, or persons with severe suicidal tendencies or self-harming behaviour, or(Nossek et al., 2018). Such serious conditions can be treated under a special jurisdiction that allows treatment or detention without informed consent and henceforth is called coercive treatment or compulsory care. Coercion clashes with principles of health care that are based on patient participation and informed consent (Sashidharan et al., 2019), a person’s right to act on their own decisions, the respect for a unique personality and their respective needs, as well as the free choice of treatment alternatives. (Tannsjö, 2004). Coercion is potentially curtailing a person’s human rights, autonomy and dignity (SOSFS, 2008:18). Despite the frequent occurrence of harm, to both staff and patients (Andersson et al., 2020) an abolishment of coercion has never been accomplished (Steinert et al., 2010).

Strained by severe psychological and emotional distress or substance abuse, individuals subjected to coercion inherit a potential for vulnerability (Svenska Psychiatriska Föreningen, 2013). That does not mean said persons are powerless or assume a victim status, instead it means that values, knowledges, and institutional mechanisms within psychiatry can create or increase a power imbalance (Norvoll et al., 2017). Power imbalance then can decrease the chance for communication and involvement on equal terms and create possibilities for abuse of power and oppression (O’Brien & Golding, 2003). Power imbalances therefore pose multifaceted challenges from legal, ethical, and therapeutic perspective. (Diseth et al., 2011). A person’s need for care, their ability to make informed judgments and potential harm to themselves or others must be assessed to justify compulsory care. Furthermore, available treatment must be able to restore the patient’s autonomous decision-making ability and improve their health while all potential negative side effects can be justifiable (Svenska Psychiatriska Föreningen, 2013). These assessments however cannot only be made on factual, objective grounds and are therefore inherently value laden (Pelto-Piri et al., 2016). A common denominator of these decisions is the use of normative concepts and formulations and their grounding in implicit knowledges and believes. For example, defining informed decision,

4

autonomy or health improvement is highly dependable on a subjective interpretati0n of legal

or scientific reasoning.

In the years 2017-2019, while working as health care assistant (sjukvårdsbiträde) within an in-patient psychiatric ward I experienced situations that posed moral challe nges and created ethical dilemmas. Amongst my colleagues I observed a diversity of perspectives, approaches and opinions regarding such situations. Informal inquires left me with the question of how ethical dilemmas are experienced and resolved. Writing my master thesis provided me with the opportunity to follow my curiosity while also striving for what Manning (1997) calls moral

citizenship: the obligation of the social worker to elucidate on ethical problems to facilitate

social change and enable democratic dialogue. This endeavour led me to take an active stance as an advocator for social justice, for strengthening the right of disadvantaged individuals and to diminish existing inequalities by identifying and addressing oppressive mechanisms (Weinberg, 2018). Norvoll et al. (2017) argue that the existing measures to improve psychiatric care fell short in paying attention to inherently ethical aspects. Bruun et al. (2018) point out that despite the frequent occurrence and complexity of ethical challenges within psychiatry the measures to counter these problems are widely underdeveloped. Also, it was found that staff’s ethical awareness and the ability to identify and describe ethical problems should be improved (Hem et al., 2014). Failing to reflect on ethical challenges has been found to be a source of overuse of coercion and inequality in treatment (Montaguti et al., 2019). Following the suggestion of Kam (2014) this study utilizes the experience of frontline-workers to inform social change efforts. I therefore decided to focus this study on the ethical challenges of coercive psychiatric care as experienced by psychiatric staff. The identification of ethically challenging experience provides insight that can contribute to improvement of ethical conduct (Weinberg, 2014). Thus, this knowledge is relevant to inform future practice and increased reflection on ethical challenges within psychiatry, consequently improving the quality of care reduce coercion and finally increase social justice. In summation, this study has been targeted to explore coercive practices within psychiatry as they are potentially harmful to staff and patients. Since efforts to reduce coercion benefit from ethical reasoning I chose to focus on ethical dilemmas in connection to coercion. To enable change, a critical perspective was chosen to investigate the norms, values and implicit knowledge which are source for justification of coercion. The focus on power differences allows to discover abuse or oppression but also identifies where change is possible in current practice

1.1 Purpose and Research

The purpose of my study is to investigate frontline-workers’ experiences of ethical dilemmas regarding coercive psychiatric care for adult patients.

From this purpose derives my research question:

Which underlying conditions, context, values, power differences and ethical frameworks are involved in the experience of an ethical dilemma in psychiatric care for coerced patients?

5

2

BACKGROUND AND PREVIOUS RESEARCH

Identifying relevant literature was done in several steps over the period several months1. The process was purposeful rather than systematic. The starting point of the literature search was to identify books and articles that concerned psychiatry, coercive treatment, discourse analysis and healthcare ethics utilizing the mälardalens högskolan’s library-database. From this initial search relevant fields of interest, authors and key words were identified. Consecutively more focused searches were conducted mostly aimed to identify relevant research articles . In this regard I also identified literature from texts’ reference lists and searched for additional literature from authors that frequently appeared during searches. This way I narrowed my focus to research that was most in line with the field of inquiry. Although the initial steps of literature resulted in large numbers of findings enabling me to focus on the most recent research the very focused search especially regarding ethics in regard to coercion resulted in only few findings. I therefore decided to regard relevance for my study as a stronger criterion than for example novelty. However, recent research was preferred, when available, especially regarding clinical studies. In line with my literature search the following chapter first presents information about the background of coercion and gradually narrows its focus to specific ethical dilemmas.

Foucault’s historical analysis of madness

The choice to start the presentation of previous research with the work of Foucault has several reasons. Firstly, reading Foucault’s texts demarcated the starting point of my literature research. The second reason is the immense importance of Foucault’s thought on the theory and perspective that guided my study. Additionally, this paragraph demonstrates how discourse research on psychiatry can concern a very wide scope of societal processes. Lastly Foucault’s research regarded the time span from the antiquity until the modern age which is much wider and earlier than all my other sources.

Foucault conducted the genealogical analysis of the history of madness by analysing historical text and art that extended to gain understanding how and from where psychiatry arose as a modern science (Foucault, 2000). This research revealed that societal developments created rather rapid shifts and changes in the treatment of people with psychiatric disease (Foucault, 2002). Foucault (2012) argued that madness must be seen neutral as a form of knowledge or adaptation to the world. Additionally, Foucault (2002) descripted circumstances were madness wasn’t seen as negative but for example an expression of godliness, or artistry. In contrast the problematization of madness from regnant groups, has repeatedly served the function that exceeded the scope mental health. Foucault argues for example that

1 At one time during my study, it was unclear if I would get permission to conduct interviews. At this

time, I decided to extensively complement my initial literature research in case I would be forced to change my study design into a literature research. While gaining a wealth of new information this also created a less linear way of literature search

6

institutionalizing mad people was used as means to control the poor, to discourage them to lead unproductive lives or to imprison them without the need of a justice system. Wider implications were for example reinforcement social order and ethical or religious dogmas. The establishment of medical institutions for treating the mentally insane cleansed the treatment of the mad from moral or religious connotations and instead accentuates its scientific value. Still psychiatry remained a normative force where the cure of madness means a return to normal behaviour (Foucault, 2002) by utilizing codified practices such as prescriptions and treatments (Foucault, 2000). Foucault also points out that the development of mental institutions outside of the frame of the hospital generated the outsider role in the medical realm that psychiatry still inherits in the modern era (Foucault & Rabinow, 1986).

2.1 Coercive practices in Swedish psychiatry

2.1.1 Historical development of Swedish psychiatry

Svensson (1996) identified the first practices of compulsory care in Swedish healthcare in the 1300s. Mad people were not considered as humans and referred into the responsibility of medical or clerical personal before the 1800’s. The first specialized treatment with corresponding facilities was established in 1824. Georg Engström who led one of the hospitals publishes the first diagnostic manual in 1832 (Hildebrand Karlén, 2013). The development of specialized treatment and diagnostics contributed to the establishment of psychiatry as science in its own right as early as 1860 (Flygare, 1999). At the turn to the20th century, compulsory care debuted including treatment additional to incarceration (Svensson, 1996). The first law to coercively treat people was aimed to mitigate social damage of exuberant alcohol and in 1927 the first specialized psychiatric ward opened in Malmö (Flygare, 1999). Treatment in this and similar wards was always involuntary until 1931 (Flygare, 1999) when intensive efforts were made to strengthen the focus on treatment (Christophs, 2002). In the wake of several pharmaceutical discoveries, the focus of psychiatry shifted towards medicine (Jersild, 2000) and enabled the development of more open institutions and treatment approaches (Flygare, 1999). In this shift of paradigm, prevention and voluntary treatment became more important than coercive treatment (Christophs, 2002). This trend was amplified by the growing influence of psychoanalysis and resulted in the sector psychiatry reform that aimed at closing large state institutions and shifted towards a treatment embedded in community (Jersild, 2000). Compulsory treatment of substance users however retained repressive tendencies. Public movements that pressed for the criminalization of drug and alcohol use started in the 1930s (Hildebrand Karlén, 2013) and in 1989 the consumption of illegal drugs was considered a crime. In 1982 the law on compulsory care for substance abusers (LVM) was crafted under the jurisdiction of the National Board Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen) (Christophs, 2002). Despite virtually no available scientific research on efficacy of used measures, the law was further tightened in 1989 (Arlebrink & Larsson-Kronberg, 2005). Regarding psychiatry as a whole, the deviance from the medical tradition was only temporary. The publishing of the first Swedish translation of the DSM III diagnostic manual demarcated a return to the biomedical focus of Swedish psychiatry (Hildebrand Karlén, 2013). In the 1980s Sweden stood out in

7

comparison to other countries with a high frequency of coercive care as coercive care was always justified when a person suffered from a psychological disease. To counteract this trend, the requirement for coercive care was changed to include the need for treatment and the introduction of the term serious mental disorder (allvarlig psykisk störning). In this line of legal formulation, legislation on psychiatric coercive care (LPT) and forensic psychiatric care (LRV) were introduced 1992 (Svensson, 1996). In 1994 the restructuring of psychiatric institutions and the responsibilities between municipality, provinces and state resulted in the organization of mental health care as they remain until today. As of 2000 general Swedish psychiatry ranked below global average, raising doubts if the self-prescribed goal of providing the best available treatment is met (Jersild, 2000). Swedish psychiatry retained a strong biomedical focus (Hildebrand Karlén, 2013) for example in regard to newer developments on research focus of genetics and neuropsychiatry (Jersild, 2000), overreliance on randomized controlled trials regarding evidence-based practice (Sundgren, 2011) and the reliance on data of foreign agencies as for example the US-American food and drug administration FDA (Topor & Denhov, 2011).

2.1.2 Current psychiatric care in Sweden

Psychiatric care in Sweden is embedded within the larger healthcare system. Healthcare and psychiatric care share the same standards for quality of care and legislation according to the Swedish law on healthcare Hälso- och sjukvårdslag (HSL). Special legislation regarding coercive treatments in psychiatry has supplementary character (Lag om Psychikiatriskt Tvångsvård, 1991:1128). Consequently, principles such as patient participation, humane and

appropriate treatment, respect for a person’s integrity, the focus on harm prevention and the

patients’ right to the best quality of care available, are also guiding compulsory care. According to the Swedish board of health and welfare, legislation on coercive practices serve the assurance of legal security, transparency and safeguarding of equal treatment (SOSFS 2008:18).

Legislation regarding coercion

The coercive care of adults in Sweden is largely regulated by three laws: LPT- Lag om

psykiatrisk tvångsvård, LRV - Lag om rättspsykiatrisk vård and LVM - Lag om vård av missbrukare i vissa fall. For a better grasp of the larger context of coercion, differences and

commonalities, I decided to shortly present all three laws in this paragraph. However further on my study only concerned psychiatric care according to LPT.

LPT is mostly concerning immediate care within hospitals and psychiatric hospitals. LRV is a law that imposes forensic psychiatric care in cases when persons commit a crime while influenced by a severe psychological disorder. Forensic psychiatric care operates under the same legal principles in regard to coercive measures, and assessment for psychiatric treatment but the decision for forensic care must be part of a court ruling. The treatment for patients has to be provided by specialized psychiatric institutions for forensic psychiatric care (Socialstyrelsen, 2008). LVM is the law that regulates compulsory care of substance abusers,

8

who will be treated in specialized institutions (SiS LVM-hem). The compulsory treatment in regard to LVM is exceptional in a sense that it legitimizes imposed treatment even against an informed decision of a competent person. A second difference is that the social committee (Socialnämnden) on municipal level is responsible to apply for this form of care in court and not medical professionals as in case of other compulsory care (Christophs, 2002). Despite focusing on different problematics and groups, all three laws aim at rehabilitation and to reinstate a persons' ability to make autonomous decisions, to enable voluntary care and to ensure that positive outcomes from care are long lasting. Another shared goal is the protection of individuals and society from harm (Christophs, 2002). The Swedish legislation allows only certain, specific coercive measures. These are mechanical restraint, seclusion, forced medication, and body searches. In addition, the restriction of electronic means of communication (e.g., mobile phone, computer) and the inspection of mail and packages can be assigned by the leading psychiatrist if deemed necessary. All coercive measures have to be documented.

Procedure according to LPT

In case of a suspected serious mental disturbance as assessed by a licensed physician, a person can be brought to a specialized psychiatric institution for psychiatric assessment. This process can also be initiated or enforced by police. Examples for serious mental conditions are: psychosis, delusion, state of confusion / disorientation, severe depression, suicidal thoughts, severe personality disorders, extreme reaction to crisis, withdrawal complications, dementia, and acute drug influence (Socialstyrelsen, 2008). A physician has the possibility to decide on involuntary admission for the duration of 24 hours (kvarhållningsbeslut). Alternatively, a specialized psychiatrist can decide on coercive admission for the maximum duration of 4 days (vårdintyg). Preconditions is a person’s imperative need for specialized psychiatric in-patient care which is caused by a serious psychiatric disorder. The assessment on coercive care includes the patient’s ability to make an informed decision about their need for treatment and the dangerousness of the person to themselves or to other people. The decision on involuntary admission must be reported for court ruling. After the psychiatric assessment, a psychiatrist has the authority to order use of coercive measures if deemed necessary. Within four days a specialized senior psychiatrist (chefsöverläkare) has to confirm the necessity of coercive admission. This way the duration of coercive admission extends up to four weeks (intagningsbeslut). Any prolongation of this time period has to be confirmed by court ruling. The patient has the right for a legal consultant, a support person and must be informed about their rights and the possibility to appeal to the decision on coercive admission. There is also a procedure for converting ongoing voluntary treatment to coercive care (konvertering) when an immediate threat to the persons’ health is caused by a severe mental disorder. Additionally, there is the possibility for involuntary community care according to LPT which then is called

9 2.1.3 Frequency of Coercive practices in Sweden

In Sweden, the national board of health and welfare (Socialstyrelsen) draws national guidelines, publishes recommendations, and provides statistical reports about health care and social services. Utilizing several national statistical registers, the board provides data on amongst other psychiatric care. This way data on psychiatric care as well as the frequency of coercive measures is publicly available. A short summary of the latest available data (from 2019) gives an overview.

Patients treated under coercive care (Table 1 and Table 2), where sometimes admitted on several occasions during the year. While almost double the amount of adolescent patients where female, coercive admission of adults was predominantly regarding male patients

Table 1: coercive care 2019 Table 2: coercive community care 2019

data obtained from Socialstyrelsen (2021a)

The classification of diagnosis was categorized according to the ICD 10 standards. In all psychiatric care the predominant diagnoses were: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; mood / affective disorders as well as mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (Socialstyrelsen, 2021).

Table 3: coercive measures 2019

Coercive measures documented within psychiatric care Patients Occasions

Restraint 1.299 3.693 Seclusion 1.098 3.556 Forced medication 2.256 5.883 data obtained from Socialstyrelsen (2021a)

In 2019, in general psychiatric care the most frequent coercive measure was forced medication (Table 3). Episodes of restraint majorly lasted between up to 4 hours and on 193 occasions between 4 and 72 hours. Seclusion episodes for the most part lasted less than 8 hours and in 53 occasions between 3 and 30 days (Socialstyrelsen, 2021a).

While mechanical restraint seemed to be used rather consistent over time, an increasing trend over the course of the last 10 years can be observed in the use of seclusion and the use of forced medication and coercive care overall (Figure 1).

Statistics on coercive hospitalized care (LPT)

patients occasions patients under 18y 1767 3316 patients 18y or older 12.044 20.258

Statistics on patients in coercive community care (ÖPT)

patients occasions patients under 18y 1767 3316 patients 18y or older 1351 2267

10

Figure 1: frequency of coercion over time

data obtained from Socialstyrelsen (2021a)

2.1.4 Frequency of Coercive practices in Europe

Despite EU efforts for equal standards and measurements in healthcare in general and psychiatry in particular, the comparability of psychiatric care and the use of coercive measures is still challenging. Differences between the member countries in health-care systems and standards, definitions, as well as legislation and documentation in regard to coercive care render it imprecise to directly compare reported numbers of each country. Several research projects have been conducted to overcome this problem. A repeated study in 10 European countries researched coercive measures that patients experienced after being involuntarily admitted to psychiatric care. This research initiative called EUNOMIA found the overall rates of coercive measures in Sweden to be close to the average usage. Forced medication however was an exception with a higher frequency in Sweden compared to other countries. The staff per bed ratio which can be seen as indicator for allocated resources in Swedish psychiatry ranked amongst the highest in Europe (Kallert et al., 2005; Raboch et al., 2010; McLaughlin et al., 2016).

2.2 Previous research on coercion

The effects of coercion on patients in relation to its severity is relatively understudied (Kersting et al., 2019) and there is a lack of research on long-term effects (Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2000). Negative effects found in systematic literature reviews include death, medical complications (Kersting et al., 2019), trauma and re-traumatization, negative feelings (Chieze et al., 2019), social stigma, and distrust towards psychiatric institutions (Sashidharan et al., 2019). In a meta-study Soininen et al. (2014) found both positive (safety and attention) and negative (demeaning, traumatic) effects of coercive measures. Most qualitative studies though have

0 5000 10000 15000 20000 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Restraint Seclusion Forced medication Coercive admissions

11

shown detrimental effects of restraint and seclusion (Sailas & Fenton, 2000). Seemingly contradicting, the use of coercion itself was not found to be a predictor for decreased improvement (Kjellin & Wallensten, 2010) nor changed rates of readmission (Jaeger et al., 2013; Seo & Rhee, 2013). There are several studies that concluded that coercion can cause improvement, for example on the long-term adherence rate of addiction treatment programs (Burke & Gregoire, 2007; LaFave et al., 2008) or to assure treatment for people that cannot be reached otherwise (Kortrijk et al., 2010). The comparability of these findings is limited due to focus on different aspects of coercion and the lack of a shared definition, standards or terminology of coercion and its respective practices (O’Brien & Golding, 2003). Formal coercion for example as defined by legal terms is very different to perceived coercion (Seo et al., 2012; Norvoll & Pedersen, 2016; Wynn 2018). Some legally coerced patients did not perceive coercion and that some patients that were not formally coerced reported a high amount of perceived coercion. A partial explanation of this divergence was found in the lack of information on legal status or the usage of informal coercion (Hem et al., 2014).

O’Brien and Golding (2003) define informal coercion as the use of authority to override a persons’ decision. Informal coercion can span from giving incentives, using personal relationship as leverage (Szmuckler & Appelbaum, 2008), attempts of persuasion, stalling, to manipulation, withholding of information and threats (Bingham, 2012). Another typical example is the locked door on wards that hinder even voluntary admitted patients from leaving (Gather et al., 2019). It is not always possible to distinguish informal from formal coercive measures or voluntary compliance from forced compliance (Sjöström, 2006). Although informal coercion can be seen as less intrusive or less drastic than formal coercion or even as a means to avoid formal coercion (Nossek et al., 2018), these measures can have similar negative impacts on staff or patients e.g., trauma and feelings of powerlessness (Andersson et al., 2020). Gather et al. (2019) point out that informal coercion has no legal guidelines to follow and a lack of documentation makes abuse of these measure less likely to be discovered (Välimäki et al., 2001). As a workaround, some studies on coercion use multiple measures for coercion and include measures for formal, informal, and perceived coercion or focus on the experience of coercion. The perception of coercion was found to be dependent on how the relationship between staff and patient was experienced (Iversen et al., 2007) the possibility of participation, the feeling of being respected and the trust in the staff to act in the patient’s best interest (Andersson et al., 2020). Patient preference and familiarity with certain treatments also affected the perception of coercive measures (Georgieva et al., 2012), as well as the way they were carried out (Hem et al., 2014). Due to individual differences, Georgieva (2012) concludes that no universal assumptions can be made on either effectiveness or intrusiveness of any coercive practice. Molewijk et al. (2017) found that the lack of principled guidance creates uncertainty with staff whether a chosen coercive measure is appropriate. Furthermore, staff cannot rely on that their perception of coercion matches the experience of their patients (Ranierei et al., 2015).

Several studies focus on identifying patient or staff characteristics in correlation to the frequency of coercive measures. A comprehensive example is a complete population study that Thomsen et al. (2017) conducted by cross-referencing national statistics of Denmark. They identified factors for increased the risk of being exposed to coercive measures, for example:

12

being admitted for the first time, being a younger male with lower economic background, social struggles or with immigrant background. To eliminate patient characteristics as influence factor Steinert et al. (2001) conducted a vignette study and measured agreement to coercive care between groups of professionals, finding that agreement over compulsory admission was similar with the tendency of psychiatrist to decide for coercion and the tendency of social workers to agree the least. Age was identified as influence factor for preference of coercion. Interestingly, the decision psychiatrists made were similar to the decisions of laymen. In a Norwegian vignette study by Aaslund et al. (2018) Psychiatrists also were found to be the most likely to make decisions in favour of coercion und psychologist least likely. A positive correlation between hierarchical position and likeliness to approve coercion could be identified. Also a high degree of agreement on suggested illegal practices, showed the division between practice and legislation. Lützén et al. (2000) utilized a moral sensitivity questionnaire to research influence factors on decisions about coercion. They discovered differences in ethical judgment depending on professional status, work field or gender. Psychiatric staff was for example less sensitive to the threat of patient autonomy. These findings suggest assessments on coercion are influenced by factors other than the patient’s mental health or situation. They might partially explain regional difference in usage of compulsion even within countries e.g., Sweden (Kjellin et al., 2008) or Finland (Välimäki et al., 2001).

2.2.1 Reduction of coercion

The aforementioned research plays an important role to reinforce the development towards a decreased usage of coercion within psychiatric treatment and substantiates this process with scientific evidence. Molewijk et al. (2017) complement this aspect by pointing out the lack of evidence for coercive practices and the amounting knowledge on its negative outcomes. More specific, there is no available research that can be used as evidence for the therapeutic safety (Soininen et al., 2014) effectiveness of seclusion and restraint (Happell & Harrow, 2010) compulsory community treatment (O’Brien et al., 2009) or involuntary treatment in general (Sjöstrand et al., 2015), regarding the treatment of mental illness. Furthermore, there is dearth of evidence for whom and in which situation coercion can contribute to improved treatment outcomes (Sashidharan et al., 2019). Kersting et al. (2019) conclude that the current psychiatric practice cannot be justified by existing research. Chieze et al. (2019) conclude that both potential risk of coercive practice and the lack of evidence for its therapeutic value should amount to the decision to reduce its use as much as possible. Goulet et al. (2017) confirm a global trend towards avoiding or reducing compulsory elements within psychiatric care. To concisely present current research on efforts to reduce coercion I draw on systematic reviews. Starting with Scanlan (2010) who stated that all earlier reviews failed to produce conclusive results. Scanlan therefore chose to compare specific measures and interventions instead of whole programs. Consecutively, Goulet et al. (2017) conducted a review based on Scanlan’s findings. Both reviews found similar aspects of effective intervention programs and concluded, that research indicates that a program with a broad approach and multiple perspectives are most likely to reduce duration and frequency of restraint and seclusion. Reduction of restraint and seclusion were not correlated with higher numbers of assault or violence on the wards (Goulet et al., 2017). However only two RCT studies were included in

13

these reviews and all but one study had high risk of bias. Dahm et al. (2017) conducted a systematic literature review that only included RCT design studies. Their findings indicated that several approaches appear to be effective to reduce coercive measures. However, the overall quality of the studies was not seen as adequate for producing reliable evidence. All above mentioned reviews stated, that further research on effectiveness of coercion reduction methods is necessary. Furthermore, a better understanding has to be gained about, exactly why promising interventions are successful (Sashidharan et al., 2019). Chieze et al. (2019) pointed out the specific need for research to inform policy on the reduction of seclusion and restraint. As cumulating evidence points out that it is potentially counterproductive to only introduce the goal of reduced coercion without having a robust knowledge on procedure and alternatives how to achieve this reduction. In this sense the danger of policy mandated goals without provision of guidance or resources can contribute to a worsening of the situation in regard to safety and quality of care (Landweer et al., 2010).

2.2.2 Coercion in psychiatric practice

Studies that focused on performed coercion found disparities between research and practice. Diseth et al. (2011) point out that the number of compulsory admissions in Norway increased despite comprehensive efforts to reduce them. As presented in the earlier chapter, statistics about the use of coercion in Swedish psychiatry show a similar development. To explain the contradiction between the recommended decrease and practical increase of coercive measures, I turned to research about justification and reasoning for the use of coercion. Starting with the findings of a literature review from Happell and Harrow (2010) who researched nurses’ attitudes toward coercion and found that perceived usefulness often was a justification for potential ethical intricacies. Kersting et al. (2019) also found the conviction that evidence for therapeutic value of seclusion and restraint would exist. Unproven assumptions (Sashidharan et al., 2019) and habits (Happell & Harrow, 2010) as well as tradition (Norvoll et al., 2017), institutional culture and policy were identified as factors that were given more importance in the usage of restraint and seclusion than scientific evidence on safety or therapeutic value (Steinert et al., 2010). Wynn (2018) found that a perceived lack of alternatives to coercion was a main argument for its continued use. Another argument was the prevention of harm and injury to patients themselves or other persons (Wynn, 2018; Kersting et al.,2019) despite indications that the occurrence of injuries is higher during seclusion and restraint episodes compared to when non-coercive alternatives are chosen (Huckshorn, 2006). Other justifications for the use of coercion were the advantage of early intervention on treatment outcome (Molewijk et al., 2017) or that a majority of patients confirm the necessity of coercive measures retrospectively (Priebe et al., 2010). However personal experience of coercion can influence which coercive measures are assessed to be adequate (Mielau et al., 2016). Practical reasons like lack of staff or other resources, as well as strong hierarchical organization with lack of possibility to challenge decisions of superiors (Jansen et al., 2019) were found. Other findings suggest the conviction of professionals that a reduction of coercion is not possible, because it already is only used in extreme cases (Sailas & Fenton 2000). Accordingly, nurses described no ethical conflict in using restraint or seclusion per se. Hence, it can be said that the execution of intrusive measures like restraint or seclusion doesn’t automatically pose an ethical dilemma for staff (Hem et al., 2014; Deady & McCarthy, 2010).

14

2.3 Ethical conflicts in psychiatric practice

In psychiatry ethical decision making is essential for day-to-day practice (Landweer et al., 2011). Ethical awareness enables practitioners to identify and resolve ethical challenges and enable conscious decision making (Montaguti et al., 2019) to take an active stance for patients’ rights and to have clear standards for justification when coercion is necessary (O’brien et al., 2009). Ethical awareness has proven effective to reduce moral distress and the usage of coercion (Norvoll et al., 2017). Hem et al. (2014) argue that research and ethics should inform each other to decrease ambiguity, enable clearer practice and decreases injustice.

Studying ethical conflicts, their perception, their effect on individuals and available coping strategies has been done in a multitude of ways. Findings from interview-, survey- and focus group studies with healthcare practitioners, have found that ethical dilemmas were based on a multitude of factors that either conflicted with each other or left uncertainty. Ambiguity also remains for the definition to coercive practices, since it is a spectrum spanning formal and informal coercion with no clear border. Deliberations on coercion entail conflicting aspects for example coercion being useful to guarantee care, or being a hindrance for a relation based on trust or therapy outcome (Molewijk et al., 2015). Tension can arise from external factors like disagreement with colleagues or be internal when e.g., personal convictions clash with professional values (Deady & McCarthy, 2010). As different roles and identities overlap it is often difficult or even impossible to draw clear distinction of principles and responsibilities (Norvoll et al., 2017).

Psychiatrists’ ethical challenges

Professional roles are described to entail contradictions that are hard to reconcile. Psychiatrist for example experienced the expectation to care for patients in line with Hippocratic principles but also the responsibility to protect society from dangerous individuals (Austin et al., 2008). Influencing factors on the decision for compulsory admission have been described as unclear. The definition of capacity for example can be too narrow to match the complexity of the unique problems, situation and circumstances that accompany a mental health crisis. In contrast, legislation that leaves room for inconsistent interpretations can be perceived as too broad (Sjöstrand et al., 2015). Factors for assessing coercive care such as diagnostic classifications, severity of symptoms or ability to partake in decision making are fluctuating and changing or might be based on flawed assumptions (Eastmen & Starling, 2006). While dealing with highly circumstantial and changing problem backgrounds, psychiatrist need to make an assessment in one particular point in time (Molewijk et al., 2015). Psychiatrist report that they perceive an expectation to make accurate decisions about competence, treatment outcome and dangerousness, which are not proportional to their actual abilities (Sjöström, 2006). These expectations from different stakeholders are persisting, despite frequent incidences that indicate that decisions of psychiatrists often are flawed (Austin et al., 2008). Professional methods of decision making are influenced by the biomedical model of psychiatry and the established use of coercion for centuries of psychiatric practice (Norvoll, 2017). Despite this rather consistent background, psychiatrist describe a change of the bioethical paradigm that is driven by research on the inefficiency of coercive treatment, which changes the foundation of

15

their profession. These changes are seen both as challenging and necessary (Sjöstrand et al., 2015).

Nurses’ ethical challenges

Another well researched profession is the psychiatric nurse. Nursing practice is described as intrinsically ethical, concerning responsibility for the well-being of the patient that relies on a relationship of trust and empathy as well as sound, professional knowledge (Andersson & Fathollahi, 2020). This responsibility on its own can lead to conflicting emotions as well as clashes of personal and professional values (Lützén, 2010). Another stressor is the immediate exposure to a person’s suffering (Deady & McCarthy, 2010) which can result in a mutual nurse - patient dependability and vulnerability (Terkelsen & Larsen, 2016). Psychiatric nurses report struggles when the available treatment is perceived as insufficient or when the patient’s condition seems to worsen (Jansen et al., 2019). The particular situation of nurses being on the frontline while also being subordinated by professional hierarchy can lead to conflicts. Nurses reported being conflicted when forced to enact coercive measure when the measure was perceived as unjustified or an outcome of bad treatment conditions. Additionally, not being able to participate in important treatment decisions, achieve changes in psychiatric care practices or not daring to act in accordance to own convictions were reported (Jansen et al., 2019). Similar conflicts arose when measures were decided by colleagues, too (Deady & McCarthy, 2010). Assessments on coercion have been described as problematic due their nature of appearing in pressured situations (Lind et al., 2004). Some nurses used informal coercion to mediate between conflicting principles (Andersson &

Fathollahi,

2020). The existence of ethical struggle was seen as adequate and necessary in regard to the perceived responsibility and the potential vulnerabilities of patients. (Deady & McCarthy, 2010). A survey study conducted by Lützén et al. (2000) confirmed differences in perception of ethical dilemmas between psychiatric nurses and psychiatrist also depending on the field of work when comparing general practice with psychiatric practice.Other professions’ ethical challenges

The suffering of patients can pose a moral challenge as the ability to provide help and support is limited. This can lead to feelings of powerlessness and that one’s work is not good enough – as found in a study with Swedish psychotherapists (Dahlqvist et al., 2009). O’Donnel (2008) found in their survey study on health care social workers that ethical issues arose from a complex set of professional values that are hard to fulfil. Ethical climate in the organization was the most crucial factor for ethical stress.

The presented findings indicate that occupation/profession can have an influence on the type of ethical dilemma health care professionals experience. These differences can lay ground to fruitful discussions and support among staff (Kontio et al., 2010) and improved practice (Landweer et al., 2010) or on the contrary lead to conflicts and disagreement about treatment options and professional values (Deady & McCarthy, 2010). However, occupation is one of

16

many factors that can influence the perception ethical conflicts in psychiatric practice and several ethical conflicts seem to be perceived in similar ways across occupational lines. For example, weighing the interests of different stakeholders, like the wellbeing of the patient or the safety of staff and other patients (Kontio et al., 2010; Landweer et al., 2010) or the best interest of the patient conflicting with the needs of their relatives that are involved in support and care as well (Sjöstrand, et al. 2015; Dahlqvist et al., 2009; Norwoll et al., 2018). The implications from legislation and the lack of clear guidelines has been identified to be another shared concern (Molewijk, 2015; Sjöstrand, et al. 2015; Deady & McCarthy). Other conflicts were uncertainty about the patient’s best interest and clashes between personal and professional convictions (Hem et al., 2014, Andersson &

Fathollahi,

2020). Coercion as a means to compensate for lacks in the healthcare systems was deemed problematic, too. Lastly the misuse, overuse and the lack of awareness of ethical aspects underlying perceived conflicts on coercion can be found across occupational categories (Haugom et al., 2019; Molewik et al., 2015).Ethical deliberations on cases

Another type of research gained insight on ethical challenges by analysing cases, that were taken up with an ethical committee or an ethical consultation unit. Specific case descriptions provided information about which type of situations was most frequently perceived as challenging. Alexius et al. (2002) found that decisions on coercion were most often based on medical criteria such as symptom severance and treatment effectiveness. Legal as well as ethical aspects were partially recognized as valid but not treated with the same importance. When medical concepts failed to match the complexity of reality ethical dilemmas can arise, as found in a study on cases of coercion within Swiss healthcare (Montaguti et al., 2019). Decisions that could not be based on medicinal reasoning alone led to incoherent practice due to a lack of a clear ethical framework. A mismatch between perceived difficulties in making decision with the inability to express ethical reasoning resulted in heightened influence of personal bias. Consequences identified were: dangers of abuse, inadequate assessment and preventative cases of coercion. Molewijk et al. (2016) found that despite a heightened ethical awareness on Norwegian psychiatric wards, a tension between different principles led to perceived difficulties. They described the rupture between personal, and professional conviction on what constitutes the right and legal requirements for coercion. Notwithstanding this backing of an action or decision by legislation didn’t lead to closure when it was conflicting with personal and professional values. Clashes of principles were described as social and situational and tightly connected to changing roles and professional identities. With a similar study design Bruun et al. (2018) researched cases from Danish ethics committees. They found that different roles and expectations led to an ambiguity of responsibility and that ethical challenges arose in the context of a relationship to the patient or their relatives. These unique situations could not be accounted for when using general rules and guidelines that are drafted for all patients e.g., house rules and routines and standard treatment procedures. An uncertainty of benefits and potential harm was perceived as especially challenging when weighing short-term against long-term effects. Also, difficulties arose during cooperation with other state institutions or the wider social context of the patient. Bingham (2012) studied a

17

case to exemplify legal and ethical conflicts that arose when a patient was neither agreeing on care but nor resisting, causing an informal case of coercion. Their conclusion was that the de-facto detention, although a frequent occurrence in psychiatric care, cannot be ethically or legally justified. They promoted a strengthening of legal rights also for patients that are not formally coerced, to diminish power imbalance between psychiatry and patients.

2.4 Ethical Frameworks in psychiatric practice

The research I elucidate on in this segment focus on the aim to make ethical decisions visible by transforming them from an internal struggle of individuals (Weinberg, 2014) into a shared and debatable process, that is embedded in the broader context of institutional, socio-political background and society (Rahimi, 2014). While insight on coercive practices and ethical dilemmas in concrete context is valuable, the provision of a framework is necessary to research the relation between values, the broader background and the unique circumstances and their influence on each other (Landweer et al., 2011). Furthermore, frameworks may also improve the possibility to develop a common language for addressing ethical concerns, for debate, documentation and for policy.

2.4.1 Ethical principles

Principle ethics aims to contribute universally applicable rules, that can be guidance for specific situations, to inform decisions and behaviours (Abma et al., 2010). To increase equality in practice, principle ethics bare the advantage to offer orientation and enable to train staff to base decisions and reflective thought on agreed standards, rather than subjective convictions (Weinberg, 2018). In bioethics the principles that are commonly found in regard to healthcare are: autonomy as the right and ability to make decision independent from external interference, beneficence as the principle for doing good based on a person’s values,

nonmaleficence as in avoiding harm and unwanted consequences and justice based on equal

rights, fairness and equal worth of every human being (Zolnierek, 2007). However, there is no universal agreement and variations such as the principle of responsibility or carefulness (Wynn, 2006), respect, dignity, and safety (Kontio et al., 2010). To overcome a lack of clear ethical principles both research and practice might be informed by international conventions as Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) from 1948, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) from 2006 (Callaghan & Ryan, 2012), the European convention on human rights and biomedicine from the European Council from 1997 as well as the Declaration of Hawaii from the world psychiatric association from 1977 (Tannsjö, 2004). The entailed ethical principles are seen to inform both policy, institutional rules such as codes of conducts (Weinberg, 2018) healthcare legislation, insurance policy (Olsen,2003) and evidence-based practice (Flynn, 2002). Principles therefore entail a profound importance. In the next step I aim to elucidate on identified clashes of principles.

18 2.4.2 Conflicts of ethical principles

Autonomy vs paternalism

The respect for a person’s autonomy is based on the assumption that an adult person is the most capable person to determine their best interest (Cherry, 2010) is almost universally appreciated (Giordano, 2000). Judgement on autonomy is dependent on the capability to make informed decisions and to act in accord to rational thought. Therefore, autonomy is interwoven with the concept of free will, natural will (Hall et al., 2004), true will (Sjöstrand et al. 2015) as well as competence of informed decision making (Tännsjö, 2004) Hence, the justification of coercion is based on the assumption that a person’s capability can correctly be assessed (Olsen, 2003). Coercive acts intruding a person’s autonomy it poses a conflict of interests as well as legal and ethical principles that needs to be accommodated (Nossek, 2018). One possibility to justify infringement of autonomy is a paternalistic standpoint. In contrast to autonomy, paternalism means that a person’s best interest is distinguished by someone else than the person themself. Arguments for paternalism could be a greater knowledge or experience or the inability of the concerned person’s autonomous decision-making capability (Zolnierek, 2007). In psychiatric practice paternalistic disruption of a patient’s autonomy is justified with being in the person’s best interest, restoring their autonomy or by assuming a patients’ natural will (Hudson, 2019). Another line of argument identified is that it is not the coercive practice that disrupts the patient’s autonomy but instead the underlying condition (O’Brien & Golding, 2003). This reasoning, however, can lead to a fallacy that every coercion is justified, once a person is assessed of not being competent, possibly resulting in overuse or abuse of coercion, inadequate ethical reasoning, bias on treatment decisions and otherization of patients (Olsen, 2003). Hudson (2019) add that the assumption of knowing a patient’s true will or best interest can lead to dismiss every unwanted wish or behaviour of the patient as caused by mental disease. Another danger is that the resistance of a patient against a treatment may not be seen as a valid expression of disagreement when the patient is assessed as not competent (Callaghan & Ryan, 2012). As a result of arising challenges some research is focused on clearly distinguishing the limits in which paternalism can justify coercion. As pointed out by Sjöstrand and Helgeson (2008) the only permissible justification for coercion is the restauration of autonomy, which is only valid if a person lacks capacity to make informed decisions and when the coercive measures are aiming at improving the patient’s situation (Nossek, 2018). The lack of capacity in this regard cannot be applied on a general level but must only concern specific decisions that are relevant for treatment. Consequently, the restoration of autonomy that exceeds decisions relevant for treatment are not the responsibility of psychiatry and therefore cannot justify paternalistic reasoning. As in somatic healthcare, a competent person must be allowed to make decisions even if they are seen as wrong by experts. By implication that prohibits assessing a person’s autonomy solely on the refusal of psychiatric care (Sjöstrand & Helgeson, 2008). Still upholding these stricter criteria would not prevent all criticism. Williamson (2014) for example criticized the concept and definition of autonomy as idealistic and misleading, neglecting a person inter-dependability in social relations. Similarly, Abma et al. (2010) argue that in a social reality where people rely on and support each other, absolute autonomy is impossible. Autonomy as a dichotomous criterion can therefore not serve as a variable for decisions on coercion. Rather autonomy and paternalism should be regarded as a continuous spectrum (Olsen, 2003).

19 Beneficence vs non-maleficence

When it is established that a person’s coercive treatment is justified another assessment concerns the balance between benefits and the harm the patient might experience undergoing certain measures. This process can have influence on coercion as some psychiatrist decide against coercion even if is justified, when potential harm outweighs the expected benefits (Sjöström, 2006); and also determine the specific course of action chosen for the coercive treatment. The inherent challenge is that neither positive nor negative outcomes of any measure can exactly be determined (Cherry, 2010). To avoid not being able to act at all when a person is suffering (Weinberg, 2018) availability of possible best treatment and high probability of treatment success can serve as proxy (Szmuckler & Appelbaum, 2008). Justification then is only possible for the least restrictive coercive measure that will achieve improvement (O’Brien & Golding, 2003). Hudson (2019) specify that coercion is not justified when it is only aimed at avoiding future harm.

Safety vs risk

Weinberg (2018) implicates, that psychiatric institutions are influenced by a societal and economic development that aims for risk assessment and risk control, in consequence imposing normative judgement and corrective measures on people that might be experienced as a high risk to an established order. Cleary et al. (2009) found that the expansion of community care only left the most severe problems for hospitalization, creating a response of increased safety measures, such as a drastic increase of locked wards. However, they add that this measure also was used to exert more control on patients and to be able to use staff more efficiently. This development practically puts psychiatrist in charge of both patient care and the safety of society even though this role is neither explicitly stated nor legally substantiated. This contradiction can leave psychiatric professionals in a tension field of conflicting interests (Hudson 2019). Risk avoidance builds on the assumption that it is possible to exactly determine or predict risk or dangerousness (Wynn, 2006). Contrastingly Cherry (2010) found that the accuracy of psychiatric risk assessment is not higher than common sense judgements, leaving doubts on the trustworthiness of these assessments. Callaghan and Ryan (2012) propose to abolish the double agency of psychiatry and solely focus on treatment by removing the risk of future harm from the assessment of need for treatment. Concerning future harm Szmuckler and Appelbaum (2008) elaborate that neither in criminal justice nor in somatic care prevention of future harm is used for coercion and that an exception of this rule for psychiatric practice is not reasonably justifiable.

Protection of individuals vs protection of others

Health care professionals serve the purpose to offer care while also being responsible for the safety of staff and other patients, forcing them to make decisions about coercion that are not primarily concerned with the need for treatment (Landweer et al., 2010). These decisions cannot be made objectively, and the protection paradigm could even result in coercing persons

20

with capacity(O’Brien & Golding, 2003). Giordano (2000) identified that in the justification for coercive treatment risk assessment varied depending on the person who is at risk and differ on whether individuals are assessed to be danger to themselves or to be a danger to others. It could be argued if cases of detention of people that endanger others is justified are the responsibility of psychiatry. A clear distinction between involuntary detention and involuntary treatment must be made (Sjöstrand & Helgeson, 2008). In this regard Szmuckler and Appelbaum (2008) emphasise that protection of others cannot be regarded as aim of health care hence, it cannot justify coercive treatment. Similarly, Tannsjö (2004) argue for a strict division of the criminal justice system and psychiatry to avoid overlaps and conflicting responsibilities.

Patient participation and responsibility

The participation of patients in treatment is embedded in the principles of health care, it’s positive impact on outcome is confirmed by research and furthermore it is strengthening democratic processes. The ethical advantage of self-management of chronical diseases (as many mental diseases are) coincides with economical effectiveness (Williamson, 2014). However, enabling participation in psychiatric care has proven to be challenging. A high degree of participation would mean to only provide information to patients and let them make all decisions themselves. However, this may be an overwhelming task and experienced as a lack of support especially in a mental health crisis. A balance between expert advice, moral support and participation must be found. While providing support, participation can be increased by involvement of persons of trust and legal representatives. Furthermore, advanced directives in which people can state their wishes and preferences for treatments in case of crisis was suggested (Liégeoi & Eneman, 2008). Additionally, a reduction of paternalistic actions that rob patients of the chance to overcome their problems themselves, potentially reducing their ability to cope and experience self-efficacy would be necessary (O’Brien & Golding, 2003). That would even imply to let patients make seemingly unreasonable decision if they are not harmful (Zolnierek 2007), but also transferring some responsibility for harmful consequences of a person’s actions from the psychiatric staff back to the patients (Williamson, 2014). On a larger scope patient participation would need to create possibilities for involvement and influence on public health policy balancing individual interests against collective interests. Williamson (2014) warn that an increase of participation should not only be based on economic justification.

2.4.3 Disadvantage of principle-based ethics

Although, principle-ethics seem to be the predominant approach for the development of policy and practice guidelines (Zolnierek, 2007), several researchers point out its limits and drawbacks. Principles are an abstract construction with unclear definition and limits. The level of abstraction makes principle- ethics hard to translate into concrete practical advice (Dellwing, 2010) as it would be necessary to be able to know and assess all rele vant information and reach an unbiased conclusion (Abma et al., 2010). This impossibility leads to a difference in interpretation potentially causing incoherent practice. As Alexius et al. (2002) found in a

21

study with Swedish psychiatrist, despite shared definitions of principles no consensus could be found in how to apply them to cases. Another aspect is that principles might not be suitable to mirror complex realities (Lützén et al., 2000) and therefore are of very little relevance for everyday practice (Landweer et al., 2010). Olsen (2003) point out that principles create the impression that clear binary answers are possible to determine right from wrong even though most influence factors that contribute to these assessments are ambiguous, fluctuating and gradual between extreme positions. The universality of principle ethics could lead to an assumption that they represent an incontestable truth, rather than debatable normative viewpoints. Utilizing principles also might foster routine decision making that neglects attention to specific circumstances. In this line of thought Weinberg (2018) questions the assumptions that equal treatment and moral consensus would necessarily contribute to a better society. When practice and policy is based on principle ethics it might contribute to increased pressure on practitioners making them responsible for adequate decisions while failing to provide the necessary resources or conditions to enable such decisions - in consequence justifying economic interests with the claim to improve social justice. When utilizing principle-ethics as a framework for research Wren (2012) considers that the idealistic principles might not be shared by the participants therefore decreasing the validity of findings. Adding to that problem is that research about ethical principles is conducted retrospectively and therefore do not correctly reflect the influence on ethical principles at the point of decision making.

Supplements and alternatives to principle-based ethics

When principle-ethics fails to deliver guidance, it could lead to situations where practitioners are not able to make a decision on ethical grounds (Dellwing, 2010). Therefore, complementary, or alternative approaches are developed. The requirements for such an approach are diverse and extensive. Olsen (2003) emphasises that a practical approach needs to regard both the assessment of the elements considered in a decision as well as the decision itself. This would mean a renunciation of binary positions toward gradual measures. Furthermore, Olsen argues to extend the scope of ethical decisions making from only regarding the most critical decisions towards all decisions made, as they implicitly carry ethical considerations. Szmuckler and Appelbaum (2008) note that an ethical framework both has to enable decisions, ensure inclusion of relevant information and stakeholders and also enable discussion on ethical grounds and convictions. The normativity of underlying values and convictions of the ethical framework has to be communicated as well (Abma et al., 2010). Weinberg (2014) adds that the ethical frame must be suitable to address ethical issues that are found in the wider socioeconomic and political background and eventually foster far reaching changes.

As both ethics and psychiatric practice are embedded in social action, several researchers (e.g.: Olsen, 2003; Weinberg, 2018; Zolnierek ,2007) propose that social relationships should be a centre of ethical frameworks. The focus point of such frameworks would not be on general principles but the concrete situation in which they occur. The professionals’ focus then should be on support that could improve the situation and strengthen the patient’s stance while