Behavioral Medicine. This paper has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination.

Citation for the published paper:

Torkelson, Eva; Muhonen, Tuija. (2003). The Demand-Control-Support Model and Health among Women and Men in Similar Occupations. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, vol. 26, issue 6, p. null

URL: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026257903871

Publisher: Plenum Press

This document has been downloaded from MUEP (https://muep.mah.se) / DIVA (https://mau.diva-portal.org).

The Demand-Control-Support Model and Health among Women and

Men in Similar Occupations

Tuija Muhonen,

1,3 and Eva Torkelson2Citation:

Muhonen, T., & Torkelson, E. (2003). The demand-control-support model and health among women and men in similar occupations. Journal of BehavioralMedicine, 26(6), 601-613.

1 School of Technology and Society, Malmö University, SE- 205 06 Malmö, Sweden 2 Department of Psychology, Lund University, P.O. Box 213, SE- 221 00 Lund, Sweden 3 To whom correspondence should be addressed; e-mail: tuija.muhonen@ts.mah.se

The Demand-Control-Support Model and Health among Women and

Men in Similar Occupations

The aim of the study was to investigate the main and the interaction effects of the demand-control-support (DCS) model on women’s and men’s health in a Swedish telecom company. According to the DCS model, work that is characterized by high demands, low decision latitude and low support decreases health and well-being. Furthermore, control and support are assumed to interact in protecting against adverse health effects of stress. Earlier studies have failed to consider occupational status and gender simultaneously. Questionnaire data from 134 female and 145 male employees in similar occupations were collected. Correlational analysis supported the main effect hypotheses irrespective of gender. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses indicated that only Demands predicted women’s health, whereas both Demands and lack of social Support predicted men’s health. However, no interaction effects were found for either women or men. Further studies should probe the relevance of the model while considering gender and occupational status.

INTRODUCTION

Psychosocial aspects of the work environment appear to have bearing on employees’ well-being and health (cf. De Jonge and Kompier, 1997; Karasek and Theorell, 1990; Aronsson, 1989). There has been a dramatic increase in long-term sickness absence in Sweden during the last five years, and work-related stress is considered to be one of the underlying causes (Lidwall and Skogman Thoursie, 2001). Research efforts have been focused on assessing the role of specific work characteristics that may be stressful and also on trying to identify factors that can affect the stress and health relationship by mitigating or eliminating the harmful effects of stress (Cooper, Dewe, and O’Driscoll, 2001). Karasek (1979) combined two research traditions: one focusing on lack of autonomy and the other on the demands at work as harmful for mental health (Payne and Fletcher, 1983). During the last two decades the demand-control model (Karasek, 1979) has attracted considerable attention in stress research and has become the dominant model in exploring the relationship between psychosocial factors of the working environment and health.

There are two basic dimensions in the demand-control model: job demands and job decision latitude (also called control, Karasek and Theorell, 1990). By combining these two dimensions, four main types of jobs can be found. ‘High strain jobs’ are characterized by high demands and low decision latitude, and ‘low strain jobs’ are characterized by low demands and high decision latitude. The ‘active jobs’ have high demands and high decision latitude, whereas ‘passive jobs’ have low demands and low decision latitude. According to the model, the high strain jobs, i.e. jobs with high level of demands and low level of control, will give rise to negative health outcomes. It is the combination of high demands and low control that is crucial for health, not the demands per se. The central assumption underlying the model is that work demands contribute interactively rather than additively to predict outcome, but research based on Karasek’s (1979) demand-control model has shown inconsistent results. Several studies have found support for the main effects of control and demands, either additively or functioning as separate predictors for health and well-being (Landsbergis, 1988; Linzer et al., 2002; Pelfrene et al., 2002; Torkelson, 1997). On the other hand, many studies have failed to demonstrate the interaction effect (e.g. Beehr et al., 2001; De Croon et al., 2000; Fletcher and Jones, 1993; Landsbergis, 1988; Pelfrene et al., 2002; Torkelson, 1997). Different kinds of criticism of the model have been raised. Some point out the methodological and conceptual problems (De Jonge and Kompier, 1997; Kristensen, 1995; Van Der Doef and Maes, 1999), others have criticized it as being too simplistic a model (De Jonge and Kompier, 1997; Janssen et al., 2001). Thus, there is a need to increase the number of variables that can be relevant in the stress process.

An important extension of the demand control model was made by adding social support as a third dimension (Johnson, 1986). A decrease in health and well-being is expected to be found in the work situations that are characterized by high demands, low decision latitude and low support. The extension of the demand-control model to include social support has been advocated by several researchers (Cooper et al., 2001; Fletcher and Jones, 1993; Kristensen, 1995).

Social support can be defined in different ways, e.g. House (1981) has divided social support into four different types: emotional, appraisal, informational, and instrumental social support. Further, social support can refer to problematic situations either in private life or at work. One way to measure social support at work is in terms of the source of the support, i.e. whether support is received from one’s supervisor, colleagues/coworkers and/or friends or family (Greenglass, 1993).

Social support can have a main effect, i.e. alleviate stress directly or act as a buffer in interaction with the stressors (Cooper et al., 2001). The assumption underlying the buffering hypothesis is that support, especially under high stress, will moderate the association between

stressful experiences and health effects (Cohen and Wills, 1985). Some studies have supported the buffering hypothesis showing that support diminishes the adverse health effects of stress (Chay, 1993; LaRocco et al., 1980; Kirmeyer and Dougherty, 1988; Moyle and Parkes, 1999), whereas other studies have failed to show the buffering effects of social support (Frone et al., 1995; Jennings, 1990). Some studies have also found support for the three-way interaction hypothesis, i.e. that control and support synergistically buffer the negative effects of high demands (Janssen et al., 2001; Landsbergis et al., 1992; Parkes et al., 1994).

A considerable amount of empirical research has originated from the demand-control-support model (see e.g. reviews by De Jonge and Kompier, 1997; Van Der Doef and Maes, 1999). De Jonge and Kompier (1997) conclude in their review that a majority of the studies, especially epidemiological ones, support the model when it comes to the main effects, but that there is as yet no strong support for the interaction (buffering) hypothesis.

A random selection of participants, in order to attain a large representative sample, is often viewed as a characteristic of good research, but there are also negative sides to it, as pointed out by Kristensen (1995). One of the negative side effects is that the results show an average picture without revealing how the situation is at the specific work environments and for individual employees (Kristensen, 1995). By focusing on the stress process in a specific organization it is possible to take into consideration stress-prohibiting measures, and thereby increasing the practical implications of the results.

Earlier studies have often been conducted on either predominantly male (Janssen et al., 2001; Karasek, 1979; Linzer et al., 2002), or predominantly female samples (Albertsen, Nielsen, and Borg, 2001; De Jonge et al., 1996; Beehr et al., 1990; Landsbergis, 1988; Rodriquez et al., 2001). According to Vermaulen and Mustard (2000) it is unclear whether there are gender differences concerning the relationship between demands at work and psychological distress.

Furthermore, only a few studies have compared men and women working in the same type of job and in similar organizational settings (Piltch et al., 1994). When studies do not control for occupational status it is impossible to know whether the differences found are due to gender or status (Colwill, 1995). Van Der Doef and Maes (1999) report in their review that studies with male or mixed samples were more often supportive of the DCS model than studies with predominantly female samples. There is a need for studies that consider both gender and occupational status simultaneously when investigating the demand-control-support model. The aim of the present study was to examine the DCS model among women and men at the same organizational levels, and working with equivalent tasks in the sales division in a Swedish telecom company.

Hypotheses

The following six hypotheses (H1–H6) were tested:

1. Demands, control and social support will have main effects on health symptoms. Demands will be positively related to health symptoms (H1), whereas control and social support will have a negative relationship to health, indicating that increasing control and support are related to fewer symptoms (H2, H3).

2. There will be interaction effects between demands x control and demands x social support in alleviating the relationship between demands and health (H4, H5).

METHOD

Participants and procedure

Questionnaires together with a covering letter (explaining the purpose of the study, its anonymous character and the voluntary nature of participation) were mailed to 422 employees in a Swedish telecom company. The company develops internet based services, products and individual solutions to solve communication needs for both small and large businesses and organizations. Like other telecom companies, the studied company has had a turbulent period including several organizational changes that have resulted in the reduction of staff.

All the managers (45 women and 67 men) in the sales division were included in the study. At the non-managerial level a random sample of 155 women and 155 men among the employees in the same division was selected. Two reminders were sent to the participants, yielding a response rate of 67%.

The group of participants consisted of 134 women (40 managers and 94 non-managers), and 145 men (60 managers and 85 non-managers). Two participants had not specified their gender. The mean age of the participants was 43 years, most of them (82%) were married and nearly all (94%) were working full-time. A minority (37%) of the participants had university education and the length of employment was 15 years on average.

Measures

Demographics. The demographic questions included gender, age, education (1 = university degree or 0 = not), organizational level (1 = managerial position or 0 = not), and length of employment.

Demands. Job demands were assessed by 11 items concerning how often participants faced different stressors at work (α = .70). Items describing sources of stress, e.g. quantitative overload, home–work conflict, relationship to supervisor and colleagues, were selected from Dallner et al. (2000). These items were further developed after a discussion with a group of employees in order to guarantee that the demands were work-specific and relevant for the studied population. Response alternatives ranged from 1 (very rarely) to 4 (very often). 2

Control. Three items (α = .81) from Dallner, et al. (2000) were used to measure perceived control at work. A sample item is: ‘Can you influence decisions that are important for your work?’ Respondents rated the three items on a scale ranging from 1 (very rarely) to 4 (very often).

Social support. Perceived social support was measured by three items adopted from Dallner, et al. (2000). Participants were asked to indicate on four-point scale how often they received social support from colleagues, from their supervisor, and from their family or friends (1 = very rarely, 4 = very often) when facing problems at work. The reliability coefficient for social support was α = .55.

Health symptoms. Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) developed by Derogatis et al. (1974) was used to assess health symptoms. HSCL-25 is a widely used scale to measure psychological and physical well-being. It has been utilized in different settings, both in epidemiological studies (Sandanger et al., 1998), and in organizational studies (Bekker, Nijssen & Hens, 2001). HSCL-25 consists of 25 items measuring symptoms such as headaches, insomnia, feelings of hopelessness and tension (α = .94). The respondents indicated the intensity of different symptoms on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (not bothered) to 4 (extremely bothered).

Statistical analysis

In order to describe the sample, descriptive statistics as well as t tests and χ2 analysis (for dummy variables) were computed. To investigate the main effects of demands, control and social support on health symptoms, both correlations (Cooper et al., 2001) and multiple regression analyses (De Croon et al., 2000; Morrison and Payne, 2001) were carried out. Interaction effects were tested by using multiple regression analysis, which is a common practice (Morrison and Payne, 2001).

Health was used as a dependent variable, and demands, control, support and their interaction terms were used as independent variables in the multiple regression analysis. As the aim was to test a theoretical model (Licht, 1995), the forced entry method was used in four steps as described below. In the first step organizational level (coded as a dummy variable) was included in the regression analysis model as a control variable since the participants could be at either the managerial or non-managerial level. At the second step demands, control and support were entered into the equation. To test the interaction effects of demand, support and control, the interactions terms demand x control and demand x support were entered at the third step. Finally, at the fourth step the three-way interaction term demand x control x support was entered into the model.

Before the regression analysis was conducted, the scales for social support and control were reversed, so that high values represent an adverse condition (Johnson, 1986). The predictor variables were converted to standard scores in accordance with the study by De Croon et al., 2000. If there are interaction effects the interaction terms should increase the explained variance over and above that accounted for by the main effects, i.e. there should be a significant increment in the R2 (Cohen and Cohen, 1983) at the third and the fourth step.

To find out whether there were gender differences in the model, separate analyses were conducted for women and men. According to Albertsen et al. (2001), possible gender effects might be concealed when the analysis is not divided by gender.

RESULTS

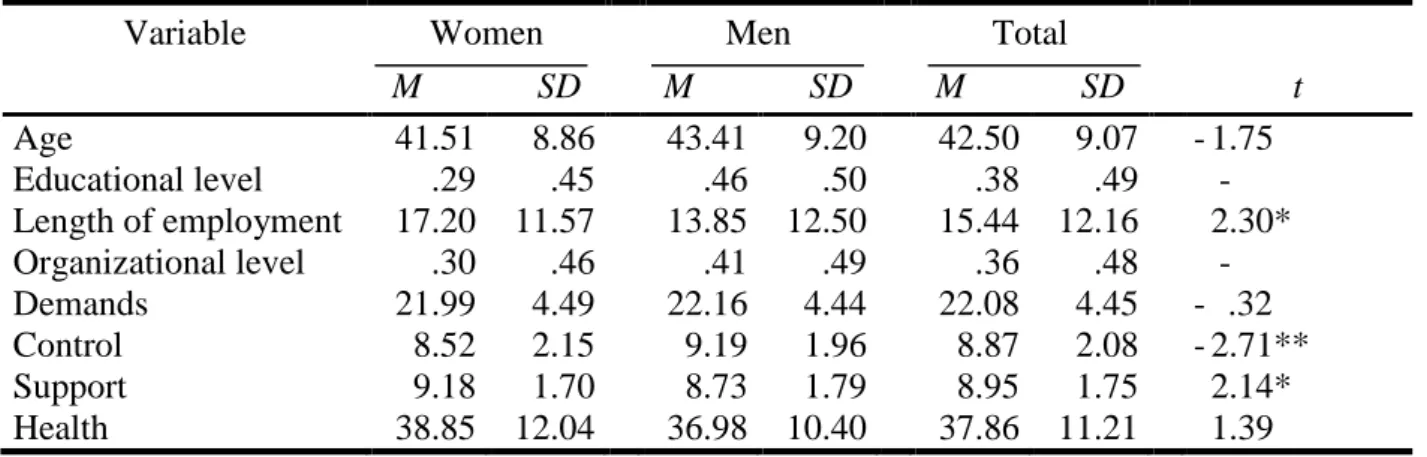

Table 1 presents means and standard deviations of the studied variables for women and men separately, as well as for the total group. Also, t-values, where appropriate, can be found in the table, indicating gender differences among the variables. There were no gender differences concerning age, demands and health symptoms. Women perceived more social support and had been employed in the company longer than men. Men had university education to a greater extent than women (X2 (1, N = 277) = 8.25, p<.01), and also, they were found more often than women at the managerial level (X2 (1, N = 279) = 4.03, p<.05). Further, men perceived more control than women.

Table 1 about here

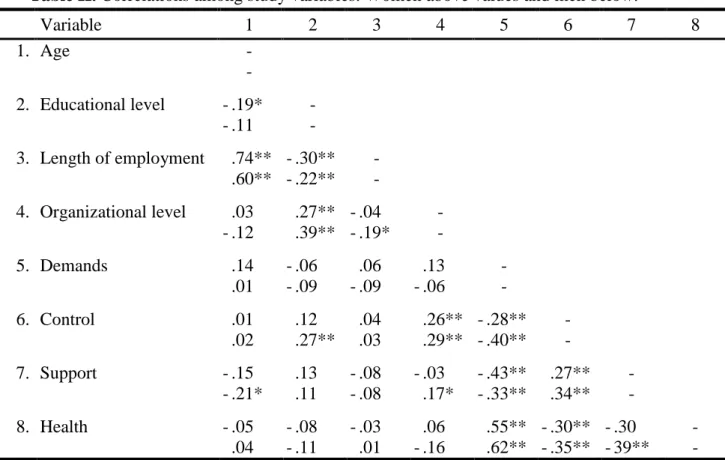

In Table 2, correlations between the studied variables can be found. The above values in the table apply for women, and the below values for men. The hypotheses concerning the main effects (H1, H2, H3) were supported regardless of gender. As expected, demands had a significant positive relationship with health symptoms, whereas control and support were negatively related to health symptoms.

both women and men. The results show that organizational level did not contribute significantly to the explained variance in health symptoms either for women or for men.

Demands had a main effect on women’s health symptoms, whereas control and social support did not contribute to increment in explained variance in women’s health symptoms. No two- or three-way interaction effects were found. This means that the results of the regression analysis for women supported only H1, whereas the other hypotheses (H2–H6) were not substantiated.

The results for men showed that both demands and social support had a main effect on their health symptoms, thereby supporting H1 and H3. Just as among women, control was not significantly related to men’s health symptoms, and thus H2 was rejected. Interaction term demands x control had a significant β-coefficient, but there is not a significant increment in R2, which means that its unique contribution to the explained variance in health symptoms was not large enough. There was no three-way interaction effect. Hypotheses 4, 5 and 6 were therefore rejected.

Table 3 about here

The overall model accounted for 33 per cent of the variance in the health symptoms for women and 46 per cent for men. The model seems therefore to apply better to men than to women in the present study.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to investigate the main and the buffering effects of control and social support based on the DCS model (Karasek, 1979) among employees in a Swedish telecom company. Women and men at the same organizational levels and working with equivalent tasks in the sales division were included in the study. In this way both gender and occupational status were considered, which has not been done in earlier studies testing the model.

The results showed a significant positive correlation between demands and health symptoms, indicating that increasing demands were related to increasing symptoms. Social support and control had a significant negative relationship to health symptoms, indicating that increasing support and control were related to fewer symptoms. These results supported hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 for the whole sample, irrespective of gender.

The results of the multiple regression analyses revealed a somewhat different picture for women and for men. Demands had a main effect for women’s health symptoms (supporting H1), whereas both demands and lack of social support acted as predictors for men’s health symptoms (supporting H1 and H3). Control did not predict health either for men or women, and therefore the results did not support H2. Furthermore, the results of the multiple regression analyses did not show any interaction effects for either demand x control, demand x support, or demand x control x support. Thus, the interaction hypotheses (H4, H5 and H6) were rejected for both women and men. A majority of the earlier studies have also been non-supportive of the interaction effects, even though they have often found support for the three factors (demands, control and support) separately affecting health and well-being (De Jonge and Kompier, 1997; Van Der Doef and Maes, 1999). The fact that control did not contribute to the explained variance in health symptoms either for women or for men may be due to shared variance among the predictor variables. It is also noteworthy that lack of social support predicted health symptoms for men but not for women. This is contrary to earlier research that has shown that social support is specially beneficial for women’s well-being (Greenglass, 1993).

no two- or three-way interaction effects were found; it is not evident that increasing control or support would decrease health symptoms for the employees. Demands appeared to be crucial for both women’s and men’s health, and therefore the most important practical implication would be to reduce the demands at work.

Karasek’s model (1979) was originally based on a male-only sample. Van der Doef and Maes (1999) conclude in their review that those studies that have not supported the model have been conducted with predominantly female samples. However, the results of the present study did not support the interaction effects either for women or for men. Whether or not the DCS model is more suitable for capturing the strain for men in their work environment than it is for women requires further study.

There are several limitations in this study that should be noted. First of all, since this is a single cross-sectional sample we cannot make causal claims about the directions of the relationships discovered. Second, the variables were measured by self-reports, which can lead to inflated correlations attributed to common method variance (Beehr et al., 2001). Third, the alpha value for social support was rather low, which can be due to the fact the measure consisted only of three items. As pointed out by Cortina (1993), alpha is affected by the number of items. This implies that it might be better to regard the different dimensions of social support separately and also use more than three items to measure each dimension. Finally, the sample consisted of a specific group of employees, and one should therefore be cautious in generalizing the results beyond the study. However, the usefulness of employing specific groups in working life to expand our understanding of the stress process has been emphasized e.g. by Kristensen (1995). The positive side of using a sample of this kind is that the studied organization has been able to make use of the results. The disadvantage is that the generalization of the results to other organizations becomes problematic.

In sum, the results of the correlation analysis showed that demands, control and social support had main effects on health symptoms regardless of gender. Increasing demands were related to increasing health symptoms, whereas increasing control and support were related to decreasing symptoms. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses, on the other hand, showed that demands had a main effect on women’s health, whereas both demands and lack of social support had main effects on men’s health symptoms. The results were not supportive of the DCS model in the sense that no interaction effects were found for either women or men. It is necessary to further investigate the relevance of the DCS model for both women and men in similar posts and occupational settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was financially supported by AFA (Labor market insurance), a Swedish insurance company, grant PA 06:00.

REFERENCES

Albertsen, K., Nielsen, M. L., and Borg, V. (2001). The Danish psychosocial work

environment and symptoms of stress: the main, mediating and moderating role of sense of coherence. Work Stress 15: 241-253.

Aronsson, G. (1989). Swedish Research on Job Control, Stress and Health. In Sauter, S. L., Hurrell, Jr. J. J., and Cooper, C. L. (Eds.), Job Control and Worker Health, Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp. 75-88.

Beehr, T. A., King, L. A., and King, D. W. (1990). Social support and occupational stress: talking to supervisors. J. Vocat. Behav. 36: 61-81.

Bekker, M. H., Nijssen, A., & Hens, G. (2001). Stress prevention training: sex differences in types of stressors, coping, and training effects. Stress Health 17: 207-218.

Chay, Y. W. (1993). Social support, individual differences and well-being: a study of small business entrepreneurs and employees. J. Occup. Organiz. Psychol. 66: 285-302. Cohen, J., and Cohen, P. (1983). Applied Multiple Regression/correlation Analysis for

Behavioral Sciences, (2nd ed.), Erlbaum, Hillsdale NJ.

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98: 310-357.

Colwill, N. L. (1995). Sex differences. In Vinnicombe, S., and Colwill, N. L. (Eds.), Women in Management, Prentice Hall, London, pp. 20-34.

Cooper, C. L., Dewe, P. J., and O’Driscoll, M. P. (2001). Organizational Stress: A Review and Critique of Theory, Research, and Applications, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl Psychol , 78: 98-104.

Dallner, M., Elo, A-L., Gamberale, F., Hottinen, V., Knardahl, S., Lindström, K., Skogstad, A., and Ørhede, E. (2000). Validation of the General Nordic Questionnaire, QPSNordic, for Psychological and Social Factors at Work, Nord 2000:12, Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen.

De Croon, E. M., Van Der Beek, A. J., Blonk, R. W. B., and Frings-Dresen, M. H. W. (2000). Job stress and psychosomatic health complaints among Dutch truck drivers: a

re-evaluation of Karasek’s interactive job demand-control model. Stress Med. 16: 101-107. De Jonge, J., and Kompier, M. A. J. (1997). A critical examination of the

demand-control-support model from a work psychological perspective. Int. J. Stress Manag. 4: 235-258. De Jonge, J., Janssen, P. P. M., and Van Breukelen, G. J. P. (1996). Testing the

Demand-Control-Support model among health-care professionals: a structural equation model. Work Stress 10: 209-224.

Derogatis L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, 1-15.

Fletcher, B. C. and Jones, F. (1993). A refutation of Karasek’s demand-discretion model of occupational stress with a range of dependent measures. J. Organiz. Behav. 14: 319-330. Frone, M. R., Russell, M., and Cooper, M. L. (1995). Relationship of work and family

stressors to psychological distress: the independent moderating influence of social

support, mastery, active coping, and self-focused attention. In Crandall, R., and. Perrewé, P. L. (Eds.), Occupational Stress, Taylor & Francis, London, pp. 129-150.

Greenglass, E. R. (1993). Social support and coping of employed women. In Long, B. C., and Kahn, E. (Eds.), Women, Work and Coping, McGill-Queen’s Univ. Press, Montreal, pp. 154-169.

House, J. S. (1981). Work Stress and Social Support, Addison Wesley, London. Janssen, P. P. M., Bakker, A. B., and De Jong, A. (2001). A test and refinement of the

demand-control-support model in the construction industry. Int. J. Stress Manag. 8: 315-332.

Jennings, B. M. (1990). Stress, locus of control, social support, and psychological symptoms among head nurses. Res. Nursing Health 13: 393-401.

Johnson, J. V. (1986). The Impact of Workplace Social Support, Job Demands and Work Control upon Cardiovascular Disease in Sweden, Dept. Psychol., Univers. Stockholm, Sweden.

Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: the implications for job redesign, Adm. Sci. Quart. 24: 285-308.

Karasek, R., and Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. Basic Books, New York.

Kirmeyer, S. L., and Dougherty, T. W. (1988). Work load, tension, and coping: moderating effects of supervisor support. Personnel Psychol. 41: 125-139.

Kristensen, T. S. (1995). The Demand-Control-Support Model: Methodological challenges for future research. Stress Med. 11: 17-26.

Landsbergis, P. A. (1988). Occupational stress among health care workers: a test of the job demands-control model. J. Organiz. Behav. 9: 217-239.

Landsbergis, P. A., Schnall, P. L., Deitz, D., Friedman, R., and Pickering, T. (1992). The patterning of psychosocial attributes and distress by “job strain” and social support in a sample of working men. J. Behav. Med. 15: 379-405.

LaRocco, J. M., House, J. S., and French, J. R. P. Jr. (1980). Social support, occupational stress, and health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 21: 202-218.

Licht, M. H. (1995). Multiple regression and correlation. In L. G. Grimm & P. R. Yarnold, Reading and understanding multivariate statistics. Washington, DC: American

Psychological Ass.

Lidwall, U., and Skogman Thoursie, P. (2001). Sickness absence during the last decades. In S. Marklund (Ed.), Worklife and Health in Sweden 2000, National Institute for Working Life, Stockholm, pp. 81-100.

Linzer, M., Gerrity, M., Douglas, J. A., McMurray, J. E., Williams, E. S., and Konrad, T. R. (2002). Physician stress: results from the physician worklife study. Stress Health 18: 37-42.

Morrison, D., and Payne, R. L. (2001). Test of the demands, supports-constraints framework in predicting psychological distress amongst Australian public sector employees. Work Stress 15: 314-327.

Moyle, P., and Parkes, K. (1999). The effects of transition stress: a relocation study. J. Organiz. Behav. 20: 625-646.

Parkes, K. R., Mendham, C. A., and von Rabenau, C. (1994). Social support and the demand-discretion model of job stress: tests of additive and interactive effects in two samples. J. Vocat. Behav. 44: 91-113.

Payne, R., and Fletcher, B. (C). (1983). Job demands, supports, and constraints as predictors of psychological strain among schoolteachers. J. Vocat. Behav. 22: 136-147.

Pelfrene, E., Vlerick, P., Kittel, F., Mak, R. P., Kornitzer, M., and De Backer, G. (2002). Psychosocial work environment and psychological well-being: assessment of the buffering effects in the job demand-control (-support) model in BELSTRESS. Stress Health 18: 43-56.

Piltch, C. A., Walsh, D. C., Mangione, T. W., and Jennings, S. E. (1994). Gender, work, and mental distress in an industrial labor force: an expansion of Karasek’s job strain model. In Keita, G. P., and Hurrell Jr., J. J. (Eds.), Job Stress in a Changing Workforce:

Investigating Gender, Diversity, and Family Issues, American Psychological Association, Washington DC, pp. 39-54.

Rodriquez, I., Bravo, M. J., Peiró, J. M., Schaufeli, W. (2001). The Demands-Control-Support model, locus of control and job dissatisfaction: a longitudinal study. Work Stress 15: 97-114.

Torkelson, E. (1997). Expert and Participatory Perspectives on Stress in Stage Artists. (In Swedish with English summary). Dept. Psychol., Lund Univ., Sweden.

Van Der Doef, M., and Maes, S. (1999). The job demand-control(-support) model and psychological well-being: a review of 20 years of empirical research. Work Stress 13: 87-114.

Vermaulen, M., and Mustard, C. (2000). Gender differences in job strain, social support at work, and psychological distress. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 5: 428-440.

Table I. Descriptive statistics of the study variables for women, men and for the total group. Variable Women M SD Men M SD Total M SD t Age 41.51 8.86 43.41 9.20 42.50 9.07 - 1.75 Educational level .29 .45 .46 .50 .38 .49 - Length of employment 17.20 11.57 13.85 12.50 15.44 12.16 2.30* Organizational level .30 .46 .41 .49 .36 .48 - Demands 21.99 4.49 22.16 4.44 22.08 4.45 - .32 Control 8.52 2.15 9.19 1.96 8.87 2.08 - 2.71** Support 9.18 1.70 8.73 1.79 8.95 1.75 2.14* Health 38.85 12.04 36.98 10.40 37.86 11.21 1.39 Note. n = 131–134 for women ; n = 141–145 for men. * p <.05, **p<.01. Potential range: Demands

Table II. Correlations among study variables. Women above values and men below. Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Age - - 2. Educational level - .19* - - .11 - 3. Length of employment .74** - .30** - .60** - .22** - 4. Organizational level .03 .27** - .04 - - .12 .39** - .19* - 5. Demands .14 - .06 .06 .13 - .01 - .09 - .09 - .06 - 6. Control .01 .12 .04 .26** - .28** - .02 .27** .03 .29** - .40** - 7. Support - .15 .13 - .08 - .03 - .43** .27** - - .21* .11 - .08 .17* - .33** .34** - 8. Health - .05 - .08 - .03 .06 .55** - .30** - .30 - .04 - .11 .01 - .16 .62** - .35** - 39** - Note. n = 130–134 for women ; n = 141–145 for men. * p <.05, **p<.01.

Table III. Summary of multiple regression analyses for predicting health symptoms for

women and men

Variable Women Men B SE B β B SE B β Step 1 Organizational level 1.10 2.08 .04 –1 .68 1.42 – .08 R 2 .01 .02 Step 2 Demands 5.04 1.13 .43** 6.07 0.83 .58** Control 1.49 1.00 .13 0.28 0.83 .03 Support 0.58 1.13 .05 2.59 0.79 .25** ∆R 2 .32** .40** Step 3 Demand x Control 1.42 0.90 .14 1.99 0.75 .21** Demand x Support – 0.96 1.03 – .08 – 0.11 0.69 – .01 ∆R 2 .01 .02 Step 4

Demand x Control x Support 0.21 0.89 .02 – 1.21 0.66 – .16

∆R 2 .01 .01

R 2 .33 .46