Raw Data for Peace and Security

The Extraction and Mining of People’s Behaviour

Yannick DellerPeace and Conflict Studies Bachelor’s Degree

15 Credits Spring 2020

Abstract

In 2015, the United Nations Global Pulse launched an experimentation process assessing the viability of big data and artificial intelligence analysis to support peace and security. The proposition of using such analysis, and thereby creating early warning systems based on real-time monitoring, warrants a critical assessment. This thesis engages in an explanatory critique of the discursive (re-)definitions of peace and security as well as big data and artificial intelligence in the United Nations Global Pulse Lab Kampala report Experimenting with Big Data

and Artificial Intelligence to Support Peace and Security. The paper follows a

qualitative design and utilises critical discourse analysis as its methodology while using instrumentarian violence as a theoretical lens. The study argues that the use of big data and artificial intelligence analysis, in conjunction with data mining on social media and radio broadcasts for the purposes of early warning systems, creates and manifests social relations marked by asymmetric power and knowledge dynamics. The analysis suggests that the report’s discursive and social practices indicate a conceptualisation of peace and security rooted in the notion of social control through prediction. The study reflects on the consequences for social identities, social relations, and the social world itself and suggests potential areas for future research.

Keywords: UN Global Pulse, Peace and Security, Instrumentarianism, Big Data and

Artificial Intelligence, Social Control Words: 13’871

We claim human experience as raw material free for the taking. On the basis of this claim, we can ignore considerations of individual’s rights, interests, awareness, or comprehension

On the basis of our claim, we assert the right to take an individual’s experience for translation into behavioural data

Our right to take, based on our claim of free raw material, confers the right to own the behavioural data derived from human experience

Our rights to take and to own confer the right to know what the data disclose

Our rights to take, to own, and to know confer the right to decide how we use our knowledge

Our rights to take, to own, to know, and to decide, confer our rights to the conditions that preserve our rights to take, to own, to know, and to decide

The surveillance capitalist’s Requirimiento1 Shoshana Zuboff

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

1 These declarations are derived from the original Requirimiento by the Spanish Conquistadores that were read

to the indigenous populations of South America. For the original, see National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox (2011), Requirimiento 1510.

List of Abbreviations

AI Artificial Intelligence

BD Big Data

CDA Critical Discourse Analysis

SDG Sustainable Development Goal

UN United Nations

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNGP United Nations Global Pulse

List of Figures

Figure 1: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:3 ... 22

Figure 2: United Nations Development Programme, 2017:7 ... 23

Figure 3: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:19 ... 23

Figure 4: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:3 ... 24

Figure 5: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:18 ... 24

Figure 6: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:6 ... 25

Figure 7: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:5 ... 26

Figure 8: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:23 ... 27

Figure 9: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:22 ... 28

Figure 10: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:22 ... 28

Figure 11: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:15 ... 29

Figure 12: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:8 ... 29

Figure 13: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:24 ... 31

Figure 14: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:22 ... 33

Figure 15: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:22 ... 34

Figure 16: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:22 ... 34

Table of contents

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Research Problem and Aim ... 2

1.2 Purpose and Research Question ... 2

1.3 Relevance for Peace and Conflict Studies ... 3

1.4 Delimitations ... 4

1.5 Thesis Outline ... 5

2 Analytical Framework ... 6

2.1 Discourse ... 6

2.1.1 What is discourse? ... 6

2.1.2 Where can we identify discourse? ... 7

2.2 Instrumentarian violence ... 9

2.2.1 Instrumentarianism ... 9

2.2.2 Violence ... 11

2.3 Theory as an Analytical Lens ... 12

3 Methodology ... 14 3.1 Three-Dimensional Approach ... 14 3.1.1 Text ... 15 3.1.2 Discursive Practice ... 17 3.1.3 Social Practice ... 18 3.2 Material ... 19 3.3 My Position ... 19 4 Analysis ... 21 4.1 Truths ... 21

4.1.1 Peace and Security ... 22

4.1.2 Data as a Resource to be Extracted by New Technologies ... 26

4.2 Power and Knowledge Dynamics ... 30

4.2.1 Knowledge ... 31

4.2.2 Power ... 33

4.3 Construction of the Social World ... 37

5 Concluding Discussion and Reflexivity ... 40

Reference List ... 43

Appendix 2 ... 48

Appendix 3 ... 50

Appendix 4 ... 51

1

Introduction

It is Wednesday afternoon; I have just finished working on my thesis. I realise that I do not have any toilet paper left at home. So, I go to my local grocery store and buy a couple of roles with my credit card – the next thing I know, I get an advertisement on Facebook for toilet paper.

This short account highlights the information society we are currently living in (Mann and Daly, 2018). Most aspects of our lives are by now quantifiable and processed as data (Mbembe, 2019). Over the last couple of years, the use of big data (BD) and artificial intelligence (AI)2 has increased in order to dissect the data we

produce and offer predictions about the future (Zuboff, 2019; Ferguson, 2016; Noble, 2018).

It is in light of these developments that in 2009 the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, announced his new initiative: UN Global Pulse, (UNGP) an initiative using big data (BD) and artificial intelligence (AI) analyses to support peace and security as well as sustainable development (UN Global Pulse, 2020). The UNGP operates via three Pulse Labs, located in Jakarta (Indonesia), Kampala (Uganda), and its headquarters in New York (United States of America) (ibid.). In recent years the Pulse Lab Kampala has experimented with BD and AI in order to analyse social media and radio broadcasts.

The celebratory responses in media and government circles might indicate that these practices could become the norm for peace and security efforts (Wallström, 2019; Verhulst and Hidalgo-Sanchis, 2019; Frischen, 2019).

1.1 Research Problem and Aim

The use of BD and AI for predictive analyses and targeted advertisement is common in the private sector, and while government agencies are slowly catching up, few have paid attention to the use of such technologies in connection to peace and security. Whereas critical scholarly attention has been given to the widespread use of BD and AI for the purposes of predictive analysis and behavioural modification in the “Western” world (Zuboff, 2019; Lyon, 2019; Noble, 2018; Thatcher, O’Sullivan, and Mahmoudi, 2016) only few have addressed other parts of the world (Couldry and Mejias, 2019; Mbembe, 2019).

The underlying discourse3 that motivates BD and AI analyses renders human

activity, behaviour, and experience as a form of raw resource that must be extracted for the purposes of prediction and modification. Human life is thus transformed into a mere object. Employing these technologies based on their underlying discourse is potentially problematic in zones of (post-)conflict as it might eliminate potential for grassroot approaches and dialogue.

It is, therefore, my aim with this discursive study to engage in an explanatory

critique of the discursive and social practices produced by the UNGP Lab Kampala.

This thesis constitutes an explanatory critique insofar as I want to explore a potential misrepresentation that is discursively produced (Fairclough, 2001). I aim at creating awareness that discourses function as a form of social practice which can contribute to the reinforcement of unequal power relations (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:88).

1.2 Purpose and Research Question

The purpose of this discursive study is to explore how the UN Global Pulse Lab in Kampala claims to contribute to peace and security efforts. I further aim at gaining a deeper understanding of the construction of social identities and relations that result from representations of truth and knowledge that are present in the report by the same

UN Global Pulse Lab. Finally, I hope to offer an explanatory critique on the asymmetric power and knowledge dynamics that are established and reproduced through an instrumentarian discourse. Therefore, I ask the following question:

How does an instrumentarian discourse contribute to the UNGP’s understanding of peace and security and what kind of social relations are the result?

I explore my research question through a critical discourse analysis (CDA) of the report by UN Global Pulse Lab Kampala named Experimenting with Big Data and

Artificial Intelligence to Support Peace and Security (2018). The following

operational questions will help to answer my research question:

§ What forms of truth and knowledge does the text assume and reproduce? § What kind of power and knowledge dynamics does the text construct? § How does the text construct social identities, relations, and the social world?

1.3 Relevance for Peace and Conflict Studies

This study ties into the wider field of Peace and Conflict Studies (PACS) in various different ways. First, this study attempts explore how the UNGP understands peace. There are a plethora of different definitions of peace, but most of them can be summed up in either negative peace, which constitutes ‘the absence of direct violence’ and

positive peace, which actively aims at bringing about ‘social justice’ through the

absence of direct as well as structural violence (Galtung, 1969:183). By understanding what kind of “peace” we are talking about, we can understand why certain actions are promoted. This aspect is a cornerstone of peace research (ibid.).

Second, there is a broad consensus amongst peace scholars that understanding the social, historical, and cultural context of any society or group is a key aspect of engaging in peacebuilding (Lederach, 2005; Reychler and Paffenholz, 2001; van Tongeren et al, 2005). The approach suggested by the UNGP contradicts this consensus by offering an understanding of peace and security that builds on social control, which can be achieved through predictive analysis. The emphasis is on

prevention without understanding the context and thus merely aiming at preventing the symptoms while ignoring underlying root causes and grievances.

Third, for such an initiative as the UNGP to exist, there has to be a conflict. Hence, Somalia and Uganda are seen as sites of conflicts. Although it is beyond the scope of this study to offer a detailed description of the specific cases in Uganda and Somalia, the UNGP initiative can be seen as a response to conflict and, thus, falls into the realms of PACS. If we understand responses to conflict, we can understand how a certain conflict is framed based on underlying assumptions.

Finally, this study opens up a space for discussion revolving around general questions such as: what is peace? How should we attain peace? Who decides what constitutes peace? Do the people living in conflict settings get a voice? What are the power relations that define the landscape of such initiatives? Essentially, I hope to inspire readers to ask themselves what the boundaries of how we should go about ensuring peace and security are.

1.4 Delimitations

As this study is following a strict qualitative design, my own bias as a researcher has to be mentioned. The data I will be gathering and analysing, although subjected to the scientific method of critical discourse analysis, is based on my understanding. I am merely offering a different reading of what the UNGP promotes as “support for peace and security”. This does not mean that my findings have no implications at all, to the contrary, it is my intention to spark a discussion on these issues.

Additionally, I am faced with time constraints. As this thesis may not take longer than two months (I hope), I do not have the opportunity to give a detailed explanation of everything I would like to address. Hence, my focus in this thesis. Even though this thesis is not implicated by any ethical considerations, I would nevertheless like to mention that in no way is it my intention to speak for people living in Somalia and/ or Uganda about their lived experiences. This is a purely discursive study focused on textual material generated by the UNGP and not field research.

1.5 Thesis Outline

The thesis consists of five chapters. The introduction should have introduced the reader to the focus I have in this study. Additionally, I have introduced the methodology as well as my analytical framework. I have positioned my research within the field of Peace and Conflict Studies while highlighting the corresponding relevance for this field of study. Chapter two, Analytical Framework, consists of an outline of theoretical points of departure for my analysis. It consists of a general discussion revolving around theoretical foundations of “discourse” as well as a specific discussion on the theoretical aspects of instrumentarianism. I have chosen not to dedicate a chapter on previous research, as I have embedded this within my analytical framework and method. In chapter three, Methodology, I outline my methodological considerations, discussing the approach to the material using a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). In chapter four, Analysis, I seek to gain an understanding of my material through instrumentarian violence as an analytical lens and CDA as a tool. Finally, in my last chapter, Concluding Discussion and Reflexivity, I reflect on my own insights and interpretations while offering an answer to my research questions. I highlight the implications of this thesis as well as potential areas for future research.

2

Analytical Framework

In this chapter, I will discuss relevant theoretical considerations for my choice of method as well as guiding principles for the analysis. As I have chosen to conduct a CDA, I will elaborate on discourse specific theoretical assumptions. I base this assumption on the notion of discourse analysis comprising a ‘complete package’ in which theoretical and methodological foundations cannot be detached from each other (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002: 4). Essentially, theory and method are intertwined and will thus be operationalised in the Methodology chapter in the form of CDA.

The discussion will, therefore, revolve around issues such as fields, intertextuality, power, and knowledge. The second part of this chapter deals with theoretical points of departure concerning instrumentarianism as logic and discourse. I will be arguing for understanding the instrumentarian logic as a form of hybrid violence encompassing elements of direct, structural, and symbolic violence.

2.1 Discourse

What follows is a general discussion and clarification on what discourse entails, how it is defined, what foundations it relies on, as well as where we can identify discourses.

2.1.1

What is discourse?

I define discourse briefly as ‘a particular way of talking about and understanding the world (or an aspect of the world)’ (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:1). Discourse is ‘a form of social action that plays a part in producing the social world – including knowledge, identities, and social relations – and thereby in maintaining specific social patterns (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:5).

The above-mentioned definition implies a set of subsequent issues which revolve around the central concept of discourse (-analysis). First, discourse analysis allows for a ‘critical approach to taken-for-granted knowledge’ (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:5). As within all social constructivist approaches to understanding the world, the claim to absolute truth is invalid. Rather, human beings are constantly negotiating the meaning of certain events and actions. This process of negotiation involves accessing reality through categories which are products of discourses (Burr, 1995:3).

Second, the knowledges we access are contingent (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:5). In other words, everything we know today is a product of historical and cultural development, and as such, there are certain forms of knowledge that are less accepted or ignored entirely. The notion of contingency implies that knowledge, reality, truth, and therefore discourses are constantly changing, some faster than others, but they are not a fixed thing (ibid.).

Third, knowledge is created through social interaction in which we construct common truths and we compete about what is true and false (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002: 5). Thus, knowledge, as well as discourse, should be seen as processes rather than fixed absolute states. Seemingly objective and absolute forms of knowledge can, therefore, be contested.

Fourth, there exists a link between knowledge and social action (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:6). Depending on what we understand to be true, we act accordingly. In other words, different social understandings of the world lead to different social actions, and therefore, the social construction of knowledge and truth has social consequences (Gergen, 1985:269). Additionally, a discourse can be seen as social action itself as it constitutes the social world, social identities, and social relations (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002). Hence, there exists a reciprocal, mutually reinforcing relationship between social action and knowledge.

2.1.2

Where can we identify discourse?

Discourse is everywhere humans are. Social and physical objects, as well as our creating of and access to them, are mediated by systems of meaning in the form of discourse (Laclau and Mouffe, 1990). This essentially means that we can see the manifestations of certain discourses in everyday objects. Granted, some might appear

to be less identifiable than others, but in essence, even a playground can be seen as a manifestation and reinforcement of discourses (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:130).

Another sphere where discourses can be identified – and where they are at work! – is in language (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:12). More specifically, discourses, discursive patterns, as well as their transformation and maintenance can be observed in text (ibid.). “Text” denotes not only a classical understanding as in “written words”, but rather refers to numerous forms, such as visuals, audibles, as well as the written word (Creswell, 2009; Chambliss and Schutt, 2019). The structure, presentation, even the selection of specific words, are all influenced by certain discourses coming into play. A text is not limited to one discourse and one discourse is not limited to one specific text. The use of language always draws on already established meanings (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:7). In other words, there exists intertextuality and

interdiscursivity (Fairclough, 1995). Intertextuality denotes the referencing (implied,

manifest, unconscious) of elements an individual text makes to other texts (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002). Interdiscursivity, on the other hand, is the sum of all discourses that are present in a text (ibid.). Consequences of intertextuality can be seen in the gradual historical development of certain discourses, knowledge, and corresponding actions based on these discourses (Kristeva, 1986:39). This applies especially within a field, which can be described as a ‘relatively autonomous social domain obeying a specific social logic or discourse’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1996:94). Therefore, actors within a field may struggle to attain the same goal (e.g. bringing about sustainable peace) and are linked to each other in a conflictual way due to their common aspiration of achieving said goal but vary significantly in how they go about attaining their goal (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:72).

Not only is a text influenced and shaped by a specific discourse, but it also reproduces or contends discourses. How texts are created is dependent on the functioning(s) of power that is at work. In other words, power is responsible both for creating the social world and for the particular ways in which that world is formed and can be talked about, ruling out alternative ways of being and talking (Foucault, 1977). Power, and by extension discourse are thus a productive and constraining force (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:14). If such a discourse becomes a constraining force, which does not allow differing interpretations or actions, then this discourse can be labelled as ideological or hegemonic (Laclau, 1990:34). These objective discourses are historical outcomes of political processes and struggles and are therefore referred

to as sedimented discourses (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:36). This is not to say that sedimented discourses cannot change over time, rather that change happens only gradually.

2.2 Instrumentarian violence

This section is dedicated to providing an understanding of instrumentarianism (Zuboff, 2019). In the second part of this section, I will provide an overview of different forms of violence and correspondingly define my understanding of violence. I then highlight, how and why instrumentarianism constitutes a form of hybrid violence. Finally, I elaborate on how theoretical foundations about discourse as well as the notion of instrumentarianism as a form of violence will be applied in my analysis.

2.2.1

Instrumentarianism

Instrumentarianism as logic or discourse refers to ‘the instrumentation and instrumentalisation of behaviour for the purposes of modification, prediction, monetisation, and control’ (Zuboff, 2019:352). In this sense, instrumentation refers to the omnipresent material architecture of sensate computation which renders, interprets, and actuates human experiences (ibid.). Instrumentation encompasses action, processes, equipment, and software necessary for big data and artificial intelligence analyses in order to mine and make sense of human behaviour through sensors.4. Instrumentalisation, on the other hand, refers to the social relations which

orient the user of such types of predictive analyses to the human experience itself (ibid.). In other words, instrumentarianism translates human behaviour and experience into (big-)data that can be collected. As a result of this translation, an architecture which is capable of making sense of this data is created. This architecture is present in the form of physical infrastructure as well as AI.

4 Sensors include devices such as smartphones, computers, and other smart accessories (fridges, watches, Alexa,

Born out of surveillance capitalism’s5 imperatives, instrumentalisation essentially

transforms the human experience, behaviour, even the very essence of “being human” into a mere commodity to be mined and transformed into profit (Couldry and Mejias, 2019; Thatcher, O’Sullivan, and Mahmoudi, 2016). Human experience, existence, and behaviour are thus transformed into objects for consumption or predictive analysis. Aspects of agency or for that matter, “will”, are deliberately (although sometimes unconsciously) erased. As a result, what it means to be human is re-defined. Human experience, behaviour, life itself is represented as computable and manipulatable through the application of technology (Mbembe, 2019:95). Therefore, instrumentarianism renders subjects and objects as a standing reserve, accessible at all times – they become Bestand (Heidegger, 1991:298; Bernstein, 1991:133-134).

Instrumentarianism as a logic or discourse is intertwined with (surveillance-) capitalism and thus requires limitless expansion (Zuboff, 2019). This results in continuous innovations in technology and the exponential growth of the material architecture (Zuboff, 2019; Couldry and Mejias, 2019; Berry, 2019). More sensors are created and new sources for data are identified in order to capture as much of the human experience as possible (Zuboff, 2019:234-235). To give an example of how this translates to our everyday life, one might think of “smart” refrigerators that analyse one’s food behaviour. These processes can be summarised in two interrelated

imperatives of instrumentarianism. First, the extraction imperative which constantly

requires that more data (i.e. raw data) is continuously extracted or mined (Zuboff, 2019:87). Second, the prediction imperative necessitates that in order to accurately predict human behaviour, ever more sources for extraction are identified (Zuboff, 2019:200-201). If both imperatives are combined, a state of certainty through social

control can be achieved (Zuboff, 2019).

Due to the limitless expansion, we are gradually habituated to technology observing and listening to us and, hence, what was once perceived as an incursion of privacy and surveillance, is now normalised (Zuboff, 2019; Ferguson, 2017). There are some who react to this process with a nod to 1984 and reference ‘Big Brother is watching’ (Orwell, 2008; Couldry and Mejias, 2019). Advocates of instrumentarianism, on the other hand, argue that as technologists, they have an

ethical obligation to alleviate suffering (Zuboff, 2019). To them, individual human beings are prone to making irrational decisions, leading to both individual and collective suffering (Ferguson, 2016). As a result of this, it is ethical to influence

individual behaviour through technology (Zuboff, 2019; Ferguson, 2016.). In these

justifications, we can identify the moral imperative of ‘if it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do so’ (Singer, 2015). Therefore, instrumentarianism aims at constructing and promoting the well-being of people through a more controlled society, where there is less unpredictable and negative behaviour (Zuboff, 2019:427-429). The goal of instrumentarianism is to replace society as we understand it with a condition of certainty based on prediction and modification of human behaviour. Consequently, instrumentarianism is a logic that aims for the totality of knowledge.

2.2.2

Violence

I understand violence in general terms as ‘present when human beings are being influenced so that their actual somatic and mental realisations are below their potential realisations’ (Galtung, 1969:168). In addition, a distinction should be made between direct, structural, and symbolic forms of violence6. First, direct violence refers to an

event in which at least one actor inflicts observable damage to a victim (Galtung, 1990). Such damage occurs in the spheres of survival needs, well-being needs, identity needs, and freedom needs (Galtung, 1990:292). Of particular interest to me is the notion of socialisation constituting a form of direct violence. Any socialisation is forced, a kind of brainwashing, while offering no choice for alternatives (Galtung, 1990:293). In connection to the instrumentarian logic then, the act of changing human behaviour based on a moral imperative through the violation of privacy of the individual, can be seen as a form of forced socialisation and, therefore, an act of direct violence upon identity needs.

Second, structural violence must be seen as a process with non-identifiable actors which has exploitation of ‘underdogs’ by ‘top-dogs’ at its centre (Galtung,

1990:292-6 I am excluding Galtung’s definition of cultural violence on purpose. Including it would exceed the scope of my

294). There exists an ‘unequal exchange’ between parties (Galtung, 1990:293). As a result of this unequal exchange, it is possible that the ‘underdogs’ experience harm (ibid.). Extracting and mining data for predictive analysis and behavioural modification without the explicit consent for such practices should be seen as a form of unequal exchange resulting from exploitation, hence constitutes a form of structural violence.

Finally, symbolic violence is exercised upon a social agent with their complicity (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 2004). This is a form of violence in which the victim and in some cases the perpetrator are not aware of committing an act of violence (ibid.). It is initially established as a result of asymmetric power relations among social groups (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 2004:272). As a result, the victim ends up being complicit in the act and perpetuation of violence. The extraction and analysis of user generated data (e.g. social media posts, call-ins to radio broadcasts) for the purposes of prediction and behavioural modification, without explicit consent for such practices, combined with complicity or negligence to this process, should, therefore, be seen as a form of symbolic violence. This is further reinforced by the asymmetric power relation between the few (technologists) who have the ability to extract and predict the behaviour of the many.

As a result of this discussion, I understand instrumentarianism as an inherently violent logic based on its exploitative processes and aim of modifying individual’s behaviour to achieve one’s own ends. Consequently, this leads to social control without the necessity of terror (Zuboff, 2019). Additionally, another violent aspect has to be seen in the asymmetric power relations between the technologists and the individuals from whom data is extracted and the complicity of the latter.

2.3 Theory as an Analytical Lens

To summarise the key features of instrumentarianism then is to, based on the prediction and extraction imperatives, extract, predict, control, and change human behaviour. These features serve as the operationalisation of instrumentarianism as a theoretical concept and thus enable me to make sense of the discursive and social practices in my analysis.

As the basis of my CDA, the theoretical point of departure of discourse highlights the powerful practices in creating certain narratives while excluding others and can, therefore, shed light on asymmetries in power relations. The concept of instrumentarianism as a form of violence serves as an analytical lens for the discursive and social practices constituted by UNGP and is complementary to CDA. Hence, I will utilise a multiperspectival approach, encompassing theoretical foundations about discourse as well as instrumentarianism as a form of violence in order to get a more thorough understanding in my analysis of the material (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:4).

3

Methodology

In this chapter, I will outline the practical application of my critical discourse analysis (CDA) method. In general, the aim of CDA is to engage in an explanatory critique of certain communicative events and corresponding social practices (Fairclough, 2001:235-236). As I have stressed in my introduction, there is a lack of critical literature in regard to utilising Big Data and Artificial Intelligence analyses for supporting peace and security efforts. I have chosen to conduct a CDA based on its appropriateness for highlighting asymmetric power relations and misrepresentations. As such, I want to focus on the critical aspect of the method in order to investigate what forms of knowledge and discourses are assumed and reproduced in the text. In conjunction with offering a critical explanation of the discourses present and actions promoted in the report, I want to highlight how discursive practices function as a form of social practice (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:88).

The chapter is divided into a description of how I intend to apply the CDA as well as an additional discussion on my motivations for choosing the material for the analysis. To conclude this chapter, I specify my own position in relation to the topic I am exploring.

3.1 Three-Dimensional Approach

What follows is a description of the practical application of a CDA. The section is divided into elaborations on textual, discursive practice, and social practice dimensions of analysis.

3.1.1

Text

Through the detailed analysis of linguistic features of a particular text, it is possible to investigate how discourses are ‘activated textually and arrive at, and provide backing for, a particular interpretation’ (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:83). In other words, by looking at the textual dimension of a text, it is possible to identify certain representations of reality. This means that I will identify what the text assumes to be true and what forms of knowledge are (re-)produced. This can be done by looking at the specific wording (Fairclough, 1992:190). The use of discourse specific words and vocabularies conveys meaning and has a normative function which excludes differing interpretations of meaning (Fairclough, 1992:191). Within a specific discourse, the meaning of words does not tend to change rapidly and, hence, presents itself as established (ibid.). The meaning that is conveyed by specific words can be investigated through the analysis of different linguistic elements. Nominalisation7, whereby a noun stands-in for a verb that conveys a process, has the effect of reducing agency and absolving an agent from responsibility (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:83). Nominalisation can be seen in, for example, the statement: ‘[…] to inform the methods of analysis and the interpretation of the results’ (Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:9; emphasis added). The noun ‘the interpretation’ stands-in for the verb ‘interpreting’. The nominalisation in this statement lets the process of interpretation appear as naturalised, while at the same time concealing who is responsible for the process of interpreting. This move could indicate a conscious removal of agency through nominalisation in order to appear objective or scientific in going about interpreting results.

Other linguistic features I use, are modality and transitivity8 (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:83-84; Machin and Mayr, 2012:105-107). I investigate modalities in the form of epistemic and deontic (Fairclough, 1992). Depending on what kind of modalities are present in the text, differing consequences for the discursive construction of social relations, knowledge, and meaning systems are the result (ibid.). The modality of truth can serve as an example. The author(s) of a text, when using an epistemic modality of truth, indicates a full commitment to the statement and its

7 Nominalisation as a linguistic feature is further explained in Appendix 1. 8 For a detailed explanation of modality and transitivity, see Appendix 1.

underlying features (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:84). As such, epistemic modality establishes an unconditional truth.

Finally, in order to highlight ideological consequences of statements, transitivity should be considered in a textual analysis (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:83; Machin and Mayr, 2012:104). Transitivity highlights how events and processes are connected or disconnected from subjects and objects (ibid.). Depending on the form (passive/active) present in the text, certain social situations may appear as normal or natural (Machin and Mayr, 2012:108.). In general, the use of a passive transitivity indicates a loss of agency on the part of the subject. The author reveals through their choice of transitivity, who is worth to be considered a subject, in essence, who is worthy of agency.

In order to better explain how these three concepts will be applied, I offer the following example:

Small data and methods of analysis used with small data cannot respond to these new challenges [new types of war, conflict, and violence]. We need to strengthen our analytical capacities, use new types of data and develop new methods. (Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:3)

An epistemic modality in the form of truth can be observed by using the word ‘cannot’ in an unconditional way. The word does not allow alternative interpretations or relativisation. The truth that is established is that ‘small data and methods of analysis used with small data’ are not sufficient for today’s challenges. Having established this truth, we can observe a deontic modality in the second sentence. This is indicated by the word ‘need’. The deontic modality that is constructed through the use of the word ‘need’ has to be seen as an obligation. This obligation, in turn, stresses the necessity of utilising ‘new types of data and develop[ing] new methods.’

This short passage uses an active transitivity, which is indicated by the relation between the subject (‘small data and methods of analysis used with small data) and how the verb ‘cannot’ is constructed. The second part of the statement – ‘We need to strengthen our analytical capacities, use new types of data and develop new methods.’ – is constructed actively as well. Based on the modality and transitivity observable in the text, I can draw conclusions about what kinds of truths and knowledges the text assumes and reproduces as well as who is endowed with agency and, thus, responsibility.

In general, the textual dimension of analysis serves to identify categories of meaning that are produced in the text. These categories are in turn used as pointers in order to explore discursive references.

3.1.2

Discursive Practice

The second dimension focuses on the production and consumption of the specific text (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:81). Aspects of consumption include how other texts could be building on the knowledge and discourses that are produced in the UNGP Kampala report. The production of a text highlights intertextuality and

interdiscursivity. In essence, I can investigate what kind of material the text is built

on (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002). I make a distinction between manifest and implied intertextuality. Manifest intertextuality is observed when the text uses direct quotation or explicitly references other material (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:73). Implied intertextuality, on the other hand, is more interpretational, as I as a researcher try to find out how the text reproduces accepted meanings and truths that were established in another text without having a clear reference.

In my analysis, I therefore use the pointers which were derived from the textual analysis. These pointers can be seen either in specific wording or in a general meaning category that is conveyed. For instance, wording that is used within a specific vocabulary might indicate an implied intertextual relationship. As an example, the word “mining” might refer to the coal industry. Through this move, I will be able to identify the discourses my text is reproducing or contesting.

Interdiscursivity refers to the various discourses that can be observed in a text

(Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:73). It highlights what kind of discourses are articulated

together in one text (ibid.). The articulation of discourses might occur in a conflictual

way, as in one discourse being staged as more legitimate or truthful than another, which in turn allows for investigations of the order of discourse (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:56). If discourses are not presented in a conflictual way, then assumptions about a creative interdiscursive mix can be made (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:73). The mix of multiple discourses and thus the creation of a new discourse, serves, on the one hand, to reinforce and reproduce truths and knowledges, and on the other hand, indicates action towards socio-cultural change (ibid.). This being said, the

analysis of discursive practices will show me how the relationship between text and social practices is mediated.

3.1.3

Social Practice

The analysis of social practices entails a dual focus. First, exploring the relationship between the discursive practice and its order of discourse (Fairclough, 1992:237). Social practices are attempts to constitute the social world, social identities, as well as social relations (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002). Correspondingly, I will be investigating the network to which the discursive practice belongs (ibid.). In general, the order of discourse refers to the system or network which constitutes what can and cannot be said (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:71). As such, the order of discourse is the sum of all the discourses, which are at play within a specific social domain or institution (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:72). Hence, the order of discourse is both a structure and a practice (ibid.).

This is where the logic of instrumentarianism will be used. Through adopting an analytical lens based on instrumentarianism, I can make sense of the socio-cultural implications created through the text (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002:86). More specifically, as I have shown in the previous chapter, instrumentarianism is built on the notion of extracting, predicting, controlling, and changing human behaviour and as such will serve as a point of reference in analysing the social world, social identities, and social relations that are constituted through the text.

Based on the three dimensions of CDA and the theoretical foundations of “discourse” I have mentioned in the previous chapter, the following guiding questions serve as my operationalisation:

§ What forms of truth and knowledge does the text assume and reproduce? § What kind of power and knowledge dynamics does the text construct? § How does the text construct social identities, relations, and the social world?

3.2 Material

My main material for the analysis will be the report on Experimenting with Big Data

and Artificial Intelligence to Support Peace and Security (Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018).

I present relevant statements in my analysis by “boxing” them rather than using direct quotations. This serves to provide context and allows the reader to easily identify the relevant statements. This being said, as I am interested in aspects of interdiscursivity and intertextuality, I must incorporate additional material9 in order to highlight how

and where the text ties in. Hence, I consider this material occupying an assisting role, whereas the document stated above is my main material of analysis (Charmaz, 2006:35).

The main material is labelled as a report. More specifically, due to the content of the document, it can be seen as a technical report since it describes the process, progress, and results of the application of BD and AI tools as well as specific software. The experimentation process lasted for three years and focused on the analysis of radio broadcasts in Uganda and social media analysis in Somalia. The report was published in 2018 and was part of the UN Global Pulse annual reporting in 2018. The document is entirely written, and solely available, in English. It is accessible only through the UN Global Pulse website or affiliated UN agencies.

Initially, I have selected this report simply out of curiosity. Its title resonated with me and as a student of Peace and Conflict Studies, everything that could potentially support peace is of interest to me. After the first reading, I chose the material as an object of my analysis due to the potential problematic socio-cultural implications; initially, my suspicion and curiosity motivated this study.

3.3 My Position

As I am writing this paper based on my own curiosity and suspicion, the choice of this specific topic stems from my overall irritation with the lack of more critical voices in response to BD and AI practices in general. More specifically, over the course of

my studies in PACS, I developed an understanding of peace as a process based on mutual respect, dialogue, and understanding the specific socio-cultural and historical contexts in which conflicts and their solution develop. This sentiment is best summed up in the concept of ‘soul of place’ (Lederach, 2005). I am troubled by the idea that predictive analyses based on BD and AI are being used in Uganda, which is still facing two wars at the moment and could potentially be further exploited by “experimentation”. At this point, I want to highlight that I do consider this work

political. This is inherent to CDA, as one tries to highlight misrepresentations and

social injustices (Fairclough, 1992). Nevertheless, I have continuously questioned my own assumptions and conclusions during the research process and will elaborate on this further in my concluding discussion10.

4

Analysis

In this chapter, I will provide the insights I have gained from my analysis. In order to make sense of my chosen material, I adopt the three-dimensional model of communicative events as outlined in the previous chapter (Fairclough, 1992). In order to answer my research question, I will follow my guiding questions and use those as analytical sections. Therefore, I will start by investigating what kinds of truths the text assumes and reproduces. The identification of assumed and reproduced truths allows for an analysis of power and knowledge dynamics, which will be discussed in the second section. The final section in this chapter is dedicated to exploring, based on the truths and dynamics the text constructs and reproduces, the constitution of the social world, social identities, and social relations. In general, the textual dimension consisting of linguistic features serves as a point of departure for investigating not only the production of truths, but additionally for indicating intertextual references. Throughout the analysis, I will draw connections to the logic of instrumentarianism and emphasise its violent aspects.

4.1 Truths

In this section, I will elaborate on the different forms of truth and knowledge the text is assuming and stating. Linguistic features such as modality (epistemic and deontic) and nominalisation serve as pointers for constructions of truth. There are two main truths that are established in the text. First, peace and security, as well as sustainable development, are phrased and represented in a particular way. Second, individuals’ behaviour and experience are labelled as free, raw data to be mined and extracted through new technologies. The textual dimension of analysis offers a point of departure into investigations of intertextuality and interdiscursivity since language can be seen where discourses are manifested, reproduced, contested, and in general articulated (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002; Fairclough, 1992). This, in turn, allows me

to explore what other texts the report is building upon – in essence, what forms of knowledge and truth the text is reproducing.

4.1.1

Peace and Security

As the title of the report Experimenting with Big Data and Artificial Intelligence to

Support Peace and Security indicates, the main goal is to achieve peace and security.

There is no clear definition offered throughout the entire text what exactly is meant by peace and security. Nevertheless, the text uses the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) as well as Agenda 2030 of the UN interchangeably for peace and security (Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:3-6).

Here, ‘Sustainable development is built’ constitutes a form of nominalisation by replacing the verb and its adverb “developing sustainably”. The effect of this move is that responsibility for the action is lost in the transformation. As such, we do not know

who is responsible for ‘sustainable development’, only what. An additional effect is

that nominalisations, in general, serve the purpose of letting events appear as if they would just happen. In other words, nominalisations as a linguistic feature can naturalise certain processes and emphasise an effect (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002). In the quote above, this means that the naturalising effect has to be seen in the effects contributing to the nominalised process. As we will see below, through the construction of this nominalisation, ‘the foundations of a peaceful, just and inclusive society and institutions’ are naturalised, in other words, declared true, for the process of sustainable development.

We can also observe the construction of an epistemic modality in this sentence. By utilising the auxiliary verb ‘is’ as a prefix to ‘built’, we are left with a condition of absolute certainty. If, for example, there would have been the modal verb “might [be]”, then certainty and hence truth could be contested. It would, therefore, allow for alternative ways of “building sustainable development”. In this case, alternative

approaches to “building sustainable development” are neglected in the text. Therefore, certainty and commitment to this particular truth are expressed and reinforced.

As one might have noticed, the first statement includes a footnote. This is an indication of manifest intertextuality. Hence, this form of truth is based on prior knowledge from another source. In this case, the sentence refers to the United Nations Development Programme report (2017):

The overall content of the sentence resembles the one from the UN Global Pulse report. There is, however, a slight difference. Whereas in the report, there is a clear, certain, and absolute conviction regarding the necessity of ‘peaceful, just and inclusive society and institutions’ through utilising ‘is built’ – in the Journey to

Extremism in Africa, this is to an extent relativised by using the word ‘calls.’

Additionally, the statement in Figure 2 clarifies that it is ‘Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16’ which ‘calls for’ and not ‘sustainable development’ in general as indicated in Figure 1. There is also no form of nominalisation regarding “developing sustainably” [goal] in Figure 2 as compared to Figure 1, and thus does not create a naturalised form as in the first statement. Hence, there is a slight discrepancy between the two statements, although the core of both can be seen as the same. Hence, the report reproduces and even exaggerates the intertextual knowledge and truth it relies on. In the report, there is another representation of how peace and security can be achieved:

It is emphasised in the text that it is ‘essential’ to be able to identify social tensions early enough in order to effectively address them. After the statement, an example from the research that UNGP Pulse Kampala has conducted, is offered. In the first sentence of Figure 3, a truth is claimed by simply using the word ‘are’ without any relativisation. Having established that ‘collective reactions powered by rumours and

Figure 2: United Nations Development Programme, 2017:7

misconceptions’ constitute the reasons for challenges to sustainable peace, we are then presented with a solution. The solution in this statement consists of ‘early identification is essential’. The word ‘essential’ indicates the urgency and necessity of the proposed action/solution consisting of ‘early identification’. As such, a deontic modality, and thus an obligation to act, is constructed. The connection between ‘challenges for sustainable peace’ and the obligation that is created in the form of ‘early identification’, implies that sustainable peace and by extension security are perceived as either reliant on or constituted by ‘early identification’. This representation of peace and security can be further observed in the following statement:

The focus here lies with ‘early warning systems’ which inform peace and security processes. Contrary to previous statements in relation to peace and security, there is no form of nominalisation present. Hence, the responsibility lies with the indicated ‘we’. The ‘we’ in this case stands for the UN Global Pulse Lab in Kampala. As a result of not constructing a nominalisation in this statement, the emphasis lies on the process itself as opposed to the effects. Hence, the process of ‘analysing data from social media and public radio broadcasts to extract insights’ is put into the foreground here. We can observe the necessity of ‘early warning systems’ and the identification of changes in the following statement:

In addition to conveying the same emphasis on the process of identification, there is another construction of deontic modality. The modality is constructed through the words ‘we need to’, hence, again, stressing an obligation in relation to ‘identify changes in the behaviour of population groups’. What is more, there is a form of nominalisation present. ‘The behaviour of population groups’ replaces “how populations/individuals behave” and thus renders an emphasis on the effect of ‘might pose a risk to others’ as a result. Through this emphasis on the effect, the proposed measures are thus constructed as necessary in relation to the effect. There is, however,

Figure 4: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:3

another form of modality which, in this case, is epistemic. The word ‘might’ points at a possibility that certain population groups pose a threat to others, and hence, the possibility requires an action in the form of the obligation I presented above. The importance of early identification is further stressed in the following statement:

In this segment, there is another form of epistemic modality in the form of truth present. It is clarified through the unconditional use of the word ‘rely’ wherein ‘effective prevention and conflict mitigation’ is dependent on identification of trends ‘as they emerge and to monitor’. Hence, the text reinforces the necessity of ‘early warning systems’, ‘timely identification’, and ‘monitor[ing]’. In addition, there are two cases of nominalisation in which the verbs “preventing” and “mitigating” are transformed into nouns. This erases responsibility and stresses the effect more than the process. Hence, the nominalised words appear as natural processes, or in other words, “it is common knowledge that”.

The textual analysis, thus far, highlights how peace and security are represented as either dependent on or equated to early identification and monitoring. In other words, prediction is the main means of achieving peace and security. Prediction which can lead to ‘effective prevention’. As a result, the representation of monitoring, early warning systems, as well as early identification and detection correspond to the instrumentarian logic, which is reliant on predicting human behaviour for the purposes of social control. I have already pointed out the manifest intertextual relationship of the report in constructing and reproducing the specific discourse on peace and security. There is, however, an additional implied intertextual relationship. If we recall Figures 1, 3, 4, and 5, and their emphasis on obligations indicated through deontic modalities, which are constructed through words such as ‘need’ and ‘essential’, we can identify an implied discourse on a “moral obligation to do good”. The implied intertextual relationship can be traced back to the notion ‘If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, then we ought, morally, to do it’ (Singer, 1971:231). We can see this narrative reproduced in an interview by Robert Kirkpatrick, director of UN Global Pulse: ‘how much privacy risk is appropriate is going to depend on the

types of harms we have an opportunity to prevent’ (Tan, 2019). A core feature of instrumentarianism lies within the proponent’s intention to utilise technological means for prediction in order to achieve the betterment of society or to do “good” (Zuboff, 2019). We can observe how this parallels with the moral obligation implied in the text – in essence, a moral obligation to bring about peace and security.

4.1.2

Data as a Resource to be Extracted by New Technologies

I have pointed out in the previous subsection that the main goal of the UN Global Pulse Lab Kampala is to support and ultimately achieve peace and security. In the context of how to achieve this goal, the following is stated in the text:

The word ‘challenge’ in this paragraph is constructed in an unconditional manner. It thus serves to create an epistemic modality of truth. It simply is as described in this text. The content of the statement then indicates that ‘traditional ways of doing analysis’ are challenged by the ‘new types of war, conflict and violence’. In general, it is never defined what exactly constitutes new types of war, violence, and conflict in the text. Additionally, the second sentence in this paragraph serves to establish another truth by creating an epistemic modality. By claiming that small data and methods of analysis ‘are no longer sufficient’, hence not allowing relativity, and without giving any reference or proof for this claim, a truth is established.

The last sentence serves to provide a solution based on a modality of obligation, which is established by inserting the words ‘we need to’ and thus stressing urgency and necessity. In addition to the obligation that is presented in the text, it is also implied that ‘new types of data’ and ‘new methods’, which enable ‘real-time and comprehensive information’ have to be seen as the solution to the previously established problem. There exists an implied intertextual relationship regarding this claim. The necessity and superiority expressed in this sentence, are manifestations of a discourse on data-ism. Brooks (2013) best describes how proponents of data-ism

refer to big data and artificial intelligence: ‘everything that can be measured should be measured; that data is a transparent and reliable lens that allows us to filter out emotionalism and ideology; that data will help us do remarkable things — like foretell the future.’ Hence, there is a similarity in the way the UNGP refers to the utility and necessity of new types of data as well as new methods of analysis, and how data-ism is coined.

The notion of traditional means and sources of doing analysis being insufficient, is further reinforced in the statement presented in Figure 1, by claiming that ‘small data and methods of analysis used with small data cannot respond to these challenges’ (Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:3). The modality in this statement is clearly emphasised by the word ‘cannot’ and, thus without a doubt, establishes an unconditional truth of small data being insufficient. As the content, as well as the modalities of these statements, indicate, the obligatory solution has to be found in big data as opposed to small data – hence, the title of the report. The following statement highlights this further:

The first sentence in this paragraph serves to create a form of deontic modality. More specifically, it creates a form of permission, which is indicated through the word ‘allows’. Hence, the permission is granted ‘to conduct analysis of big data’. This is in turn emphasised in the following sentence, which establishes an ‘exciting’ truth by comparing the utility of the new form of data to ‘other means of doing analysis’ (read: traditional, small). In addition, the word ‘QataLog’ stands in for the verb extracting and mining. It therefore has to be seen as a form of nominalisation, which erases responsibility and, in turn, emphasises the effect of ‘inform[ing] humanitarian and peace efforts’. Further, since QataLog is a tool for analysing ‘big data’ and we now know that it ‘captures people’s voices’, we can assume that people’s voices are a form of data. The process that is encompassed by ‘QataLog’ is described in the following statement:

QataLog is described as a data ‘mining’ tool, which is used to ‘extract’ data from social media and radio broadcasts. This kind of vocabulary is reminiscent of the natural resource industry (Couldry and Mejias, 2019). The text therefore draws on an implicit intertextual relationship corresponding to vocabulary usually employed in the spheres of, for instance, the coal industry11. Generally, the resources that are mined

and extracted in this industry, are labelled as ‘raw’, as in ‘unrefined’ and must, thus, be subjected to a refinement process conducted by a specialised company, in order to create value (Zuboff, 2019; Couldry and Mejias, 2019). The notion of data constituting a form of resource is visible in several instances. It is most pronounced in the following statement:

‘Data mining’ (standing-in for the verb: mining [data]) is used as a noun in this sentence, which is another form of nominalisation, in order to let the process appear

natural. Since ‘data mining’ is applied to ‘language’, we can assume that language is

perceived as a form of data. Additionally, the language Acholi is constituted here as a ‘low-resource’ language. Hence, data in this context has to be seen as a form of resource. More specifically, data is a resource that has to be mined and extracted for the purposes of analysis (read: refinement). We can therefore observe the instrumentarian logic at work in this kind of formulation. If we recall one of the features of instrumentarianism, extraction of raw data, for the purposes of prediction we can see how peace and security being represented as dependent on ‘early warning systems’ and prediction in general, we now realise that the prediction is enabled by

11 The peculiar vocabulary can be observed here: World Coal Association (2020). Figure 9: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:22

the aspect of conceptualising ‘language’ and ‘people’s voices’ as a form of raw data to be extracted. The notion of raw data being established can be seen in this statement:

In the context of analysing ‘hundreds of hours of content’ from radio broadcasts, which as we have seen earlier, is comprised of ‘people’s voices’, we can observe an epistemic modality present in the usage of the word ‘are’. The particular phrasing does not allow for any alternative interpretations except than ‘in the form of raw data’. Hence, we can see how the text establishes the truth that data from radio broadcasts is in fact raw.

I have previously mentioned how there exists an implied intertextual relationship between the specific vocabulary in this text as well as the general vocabulary utilised in the natural resource industry. There is an additional intertextual relationship, however:

The ‘private sector companies’, which are referred to in the text, are comprised of big technology companies such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon. More specifically, Google has to be seen as the founder of the data vocabulary (Zuboff, 2019; Couldry and Mejias, 2019). Therefore, by reproducing the particular vocabulary exemplified by ‘mining’, ‘extracting’, ‘raw data’, the knowledge and truth surrounding the discourse on big data and artificial intelligence analyses is reinforced. As a consequence, people’s voices, their behaviour, and ultimately their experience is constantly represented as being raw data, ready to be harnessed. We can see here another nod to instrumentarianism in the form of the instrumentation of human experience (Zuboff, 2019:352).

There is additionally one more intertextual relationship concerning the utility of big data analysis. If we recall Figure 8, we notice the emphasis in the text on how

Figure 11: Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018:15

‘people’s voices’ are captured where it was previously not possible. The content of this statement thus serves to highlight the utility and the potential big data and artificial analyses entail. The discourse surrounding this kind of sentiment is described as Data Philanthropy (Zuboff, 2019). It entails the belief that big data and artificial intelligence analyses can actually represent reality as it is, due to its unprecedented large scale (ibid.). As such, the process of instrumentalisation (Zuboff, 2019:352) is at work, insofar as the Pulse Lab Kampala is oriented towards big data in order to create early warning systems – in essence, predictive analysis. The intertextual relationship can be traced to a board member at Google, and a proponent of data philanthropy, who claims that as a result of computer mediated big data and artificial intelligence analyses ‘behaviour, which was previously unobservable, is now observable’ (Varian, 2014:30).

In summary then, by constructing nominalisations, epistemic and deontic forms of modality, as well as through manifest and implied intertextual references, the truth of the utility as well as necessity of new technologies in the form of big data and artificial intelligence analyses is reproduced. Data is represented as a raw resource that has to be extracted for the purposes of predictive analysis. The two instrumentarian imperatives, extraction and prediction, are present as a result.

4.2 Power and Knowledge Dynamics

So far, I have presented how, and what kinds of truths, are assumed and reproduced in the text. First, peace and security are represented as either dependent on or equated to early identification and monitoring. In other words, prediction is the main means of achieving peace and security. Second, new technologies in the form of big data and artificial intelligence analyses are framed as superior to old and traditional methods of analysis. In addition, content derived from individual’s experiences is to be perceived as raw data for extraction and mining.

In this section I will investigate the dynamics of power and knowledge that are created by this communicative event. In order to assess the knowledge dynamics, I will mainly focus on indicators of order of discourse as well as mixed

interdiscursivity. In the context of power dynamics, I will highlight how the text

utilises transitivity in order to assign agency in various situations.

4.2.1

Knowledge

One of the essential features of instrumentarianism is coined by ‘expansion for expansion’s sake’ (Zuboff, 2019:201). Expansion is necessitated by the prediction imperative, which states that early warning systems have to be fed with ever more data in order for accurate predictions about reality to be possible (Zuboff, 2019:199-202). Expansion creates ever new methods and sources of data collection, based on the prediction imperative, which renders instrumentarianism a logic or project of

totality (Zuboff, 2019:399). Hence, alternative approaches to data collection and

analyses are not possible within the discourse of instrumentarianism. Everything must be bigger, faster, more efficient – more total.

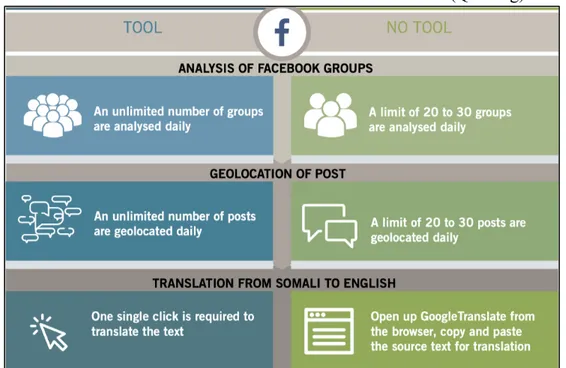

In the context of the UN Global Pulse Lab Kampala report, we can observe in

Figure 13 (below) a similar portrayal of the benefits of QataLog compared to ‘no

tool’, which refers to ‘traditional methods of analysis using small data’ (Pulse Lab Kampala, 2018). This segment serves to portray the benefits QataLog offers in relation to social media data mining and analyses compared to traditional analysis of social media. The left column describes the benefits the ‘tool’ (QataLog) offers,