J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

Can commitment save companies

from negative publicity?

The tempering effect of commitment and corporate response

on negative publicity

Bachelor thesis within Business Administration

Authors: Nanci Kasto

Elina Sargezi Micaela Tärnhamn

J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O LJÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

Kan lojalitet rädda företag från

negativ publicitet?

Den dämpande effekten av „lojalitet‟ och „företagsrespons‟ på negativ publicitet

Kandidatuppsats inom Företagsekonomi Författare: Nanci Kasto

Elina Sargezi Micaela Tärnhamn Handledare: Olga Sasinovskaya Jönköping January 2009

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge and extend their heartfelt gratitude to the following

per-sons who have made the completion of this bachelor thesis possible:

We would like to sincerely thank our tutor and mentor Olga Sasinovskaya for her guidance

throughout the writing process.

A special gratitude is dedicated to Erik Hunter, Ph.D. candidate at Jönköping International

Business School, for his patient assistance and support throughout the course of this thesis,

con-tinuously encouraging us to fearlessly plunge even deeper in our research.

Furthermore, we would like to show our gratefulness to our fellow classmates in our tutoring

ses-sion group, for their constructive feedback.

Last but not least, we thank the teachers and the questionnaire respondents for their cooperation,

allowing us to carry out our research experiment.

Nanci Kasto Elina Sargezi Micaela Tärnhamn

Jönköping International Business School 2009-01-07

Bachelor Thesis within Business Administration

Entrepreneurship, Marketing and ManagementTitle: Can commitment save companies from negative publicity?

The tempering effect of commitment and corporate response on negative publicity

Authors: Nanci Kasto, Elina Sargezi, Micaela Tärnhamn

Tutor: Olga Sasinovskaya

Date: 2009-01-07

Subject terms: Negative publicity, corporate response, commitment, brand, attitude, consumer behaviour, experiment.

Abstract

According to Faircloth, Capella & Alford, (2001), a brand is one of the most important assets a company can possess. A brand is what the consumers relate to when differentiating one com-pany from another and therefore plays a vital role for determining competitive advantage. How-ever, in the modern world, with the increasing technology advances, companies are losing more and more control of what is said and spread about their brands. What takes companies years to build can nowadays be destroyed in just a short amount of time.

When dealing with negative publicity, a company‟s actions have a crucial role in determining the outcome of the negative publicity. The theoretical literature suggests that strong respective weak corporate response, will decide whether the consumers‟ brand attitude will be improved or wors-ened. Furthermore, it is also argued that consumers‟ commitment level can temper the effects of negative publicity in the sense that the more committed a consumer is, the more he/she will re-sist a change in brand attitude. Therefore, the purpose of this study is “to examine if consumers’

atti-tude towards a brand is changed depending on strong or weak corporate response to the negative publicity. A sig-nificant aspect is to investigate and further associate the commitment variable to the outcome of change in attitudes as a result of the negative publicity.”

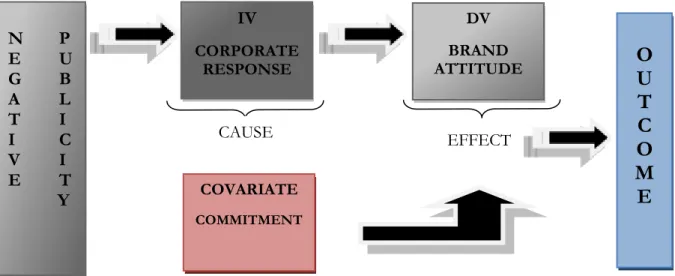

In order to determine the cause-and-effect relationship between corporate response and brand attitude, an experiment was conducted where corporate response was the independent variable and brand attitude was the dependent variable. Furthermore, the commitment variable was in-cluded as a covariate; an independent variable not manipulated by the experimenter but still ex-pected to affect the outcome. Three different questionnaires were created: 1) Negative publicity with weak corporate response, 2) Negative publicity with strong corporate response, and 3) Negative publicity only. The experiment was conducted on consumers in Jönköping.

The results indicate that whether a company decides to reply with a strong or weak corporate re-sponse to negative publicity, it will in the end have an effect on the consumers‟ brand attitude. Furthermore, the results also reveal that a consumer‟s level of commitment reinforces the effect of corporate response on his/her attitude towards a brand. In other words, the degree of the consumers‟ commitment towards a brand can temper the effect of negative publicity, ultimately saving companies from the consequences of negative publicity.

Kandidatuppsats inom Företagsekonomi

Entrepreneurship, Marketing and ManagementTitel: Kan lojalitet rädda företag från negativ publicitet? Den dämpande

ef-fekten av ‘lojalitet’ och ’företagsrespons’ på negativ publicitet

Författare: Nanci Kasto, Elina Sargezi, Micaela Tärnhamn

Handledare: Olga Sasinovskaya

Datum: 2009-01-07

Ämnesord: Negativ publicitet, företagsrespons, lojalitet, varumärke, attityd, konsu-mentbeteende, experiment.

Sammanfattning

Ett varumärke är enligt Faircloth, Capella & Alford (2001), företagets viktigaste tillgång. Varu-märket spelar en viktig roll i att avgöra ett företags konkurrensfördel, då konsumenter relaterar till ett varumärke för att kunna differentiera mellan olika företag. I takt med de ökande teknolo-giska framryckningar i den moderna världen, har företag däremot börjat förlora alltmer kontroll över det som sägs och sprids om företagets varumärke. Det som tar företag åratal att bygga upp kan numera förgöras under en kort tidsperiod.

När det gäller att handskas med negativ publicitet har företagets handlingar en stor inverkan på konsekvensen av den negativa publicitet som företaget har utsatts för. Den teoretiska litteraturen föreslår att stark respektive svag företagsrespons kommer att avgöra om konsumenternas attityd gentemot varumärket kommer förbättras eller försämras. Dessutom menar man att konsumen-tens lojalitetsnivå har en dämpande effekt på negativ publicitet. Ju lojalare en konsument är, des-to mer kommer han/hon att motstå en ändring i attityd gentemot varumärket i fråga trots den negativa publiciteten. Därmed är syftet med denna uppsats att ”undersöka om konsumenters attityd

gentemot ett varumärke ändras beroende på stark eller svag företagsrespons i förhållande till den negativa publici-teten. En betydelsefull aspekt är att utreda och associera den kompletterande variabeln, lojalitet, med de utfallande ändringarna i attityd till följd av negativ publicitet”.

I avsikt att utröna orsak-och-verkan relationen mellan företagsrespons och varumärkesattityd, ut-fördes ett experiment där företagsrespons var den oberoende variabeln och varumärkesattityd var den beroende variabeln. Därutöver, var lojalitetsvariabeln inkluderad som en covariate, dvs. en oberoende variabel som inte var manipulerad av forskarna men som ändå förväntades påver-ka resultatet. Tre olipåver-ka enkäter var utformade: 1) Negativ publicitet med svag företagsrespons, 2) Negativ publicitet med stark företagsrespons, och 3) Endast negativ publicitet. Experimentet ut-fördes på konsumenter i Jönköping.

Resultaten påvisar att vare sig ett företag väljer att hantera negativ publicitet genom stark eller svag företagsrespons, kommer resultatet att ha en inverkan på konsumenternas varumärkesatti-tyd. För övrigt visar resultaten att nivån av konsumentens lojalitet gentemot ett varumärk kom-mer att förstärka effekten av företagsresponsen på kundens varumärkesattityd. Med andra ord, graden av konsumenters lojalitet mot ett varumärke kan dämpa effekten av negativ publicitet och därmed rädda företag från degeneration av varumärket till följd av negativ publicitet.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem discussion ... 3 1.3 Purpose ... 4 1.4 Delimitations ... 4 1.5 Disposition ... 52

Frame of Reference ... 6

2.1 What is a Brand? ... 7 2.2 Attitude ... 82.2.1 The ABC Model of Attitudes ... 8

2.2.1.1 Hierarchies of Effects ... 8

2.2.2 The functionality theory ... 9

2.2.3 The impact of brand attitude and brand image on brand equity...10

2.3 Levels of involvement ...11

2.4 Negative publicity ...12

2.5 Corporate Response to Negative Publicity ...13

2.6 Brand Commitment ...15

2.6.1 Brand Commitment and Brand Loyalty ...15

2.6.2 Outcome of commitment...15 2.6.3 Resistance to change ...16 2.6.4 Constancy of Attitudes ...16 2.6.5 Counter-arguing communications ...17 2.6.6 Information processing ...17

3

Hypotheses ... 18

4

Method ... 20

4.1 Purpose of research ...20 4.2 Research method ...20 4.3 Research approach ...214.4 Data collection methods ...21

4.5 Experiment ...22

4.5.1 Choice of product category ...22

4.5.2 Choice of target brand ...23

4.5.3 Design ...23 4.5.3.1 Commitment ... 24 4.5.3.2 Brand attitude ... 24 4.6 Experiment elaboration ...25 4.6.1 Scenario 1 ...25 4.6.1.1 Negative publicity 1 ... 25 4.6.1.2 Corporate response 1 ... 25 4.6.2 Pilot Study ...25

4.6.2.1 The results from the pilot study ... 26

4.6.3 Scenario 2 ...27

4.6.3.1 Negative publicity 2 ... 27

4.6.3.2 Corporate responses 2 ... 27

4.7 Participants ...28

4.8 Procedure ...28

4.9.1 Validity ...29

4.9.1.1 Demand Characteristics ... 29

4.9.2 Reliability ...29

4.9.3 Generalizability ...30

4.10 Empirical findings received through SPSS ...30

5

Analysis ... 36

5.1 Hypothesis 1 ...36

5.1.1 Further assumptions to H1 ...37

5.1.2 Why less significance than expected? ...39

5.1.2.1 Assumption 1 ... 39

5.1.2.2 Assumption 2 ... 41

5.2 Hypothesis 2 ...41

6

Conclusion ... 46

6.1 Critique of study and method ...47

6.2 Further research ...48

References ... 49

Appendices

Appendix 1 Pilot study A: Negative publicity and weak corporate response. Appendix 2 Pilot study B: Negative publicity and strong corporate response. Appendix 3 Experiment 1: Negative publicity and weak corporate response. Appendix 4 Experiment 2: Negative publicity and strong corporate response.Figures

Figure 2.1 Three Hierarchies of Effects ... 9Figure 2.2 Evaluation and Purchase Models ... 12

Figure 4.1 Cause-and-effect relationship ... 22

Figure 4.2 The „post-test only/control group‟ design ... 23

Figure 4.3 Histogram of „Total commitment scale‟ with normality curve ... 32

Figure 4.4 Histogram of „Total brand attitude scale‟ with normality curve... 32

Figure 5.1 Correlation between „Scale of commitment‟ and „Scale of brand‟ ... 43

Figure 5.2 Correlation between „Scale of commitment‟ and „Scale of brand‟ with red and blue arrows ... 45

Tables

Table 4.1 Reliability statistics for the commitment scale (SCommit) ... 33

Table 4.2 Reliability statistics for the brand scale (SBrand) ... 33

Table 4.3 Homogeneity of regression slopes statistics... 34

Table 4.4 Statistics on Levene‟s Test of Equality of Error Variances ... 34

Table 4.5 Statistics on Tests of Between-Subjects Effects ... 35

Table 5.1 P-value and Partial Eta square for „Group‟ ... 36

Table 5.2 Difference in mean between the three groups of weak, strong and neutral corporate response ... 38

Table 5.3 Statistics on Pairwize comparison ... 39

Table 5.4 P-value and Partial Eta square for „SCommit‟ ... 41

Table 5.5 Mean for attitude towards brand, after negative publicity and corporate re-sponse (without the commitment variable) ... 42

Table 5.6 Mean for attitude towards brand, after negative publicity and corporate re-sponse (with the commitment variable) ... 42

1

Introduction

This chapter will provide the reader with a background description of the study, which in turn will lead to the dis-cussion about the problem the authors have distinguished. Followed by this, is a formulation of the purpose and the research questions. Furthermore, a disposition of the upcoming chapters and their content is depicted.

1.1 Background

More than 40 years ago, Brendan Behan, an Irish playwright, claimed that “All publicity is good- except an obituary notice” (Various authors, 2005, p.124). It did not matter what they wrote about you, all that mattered was that you got some public recognition. In those days, this made sense. Not only were there few media channels, but in the 50‟s and 60‟s, they looked different from today. There existed another sense of ethical and moral standards within journalism, one that they seldom abounded (Stewart, 2002). With time, and the development of society, all of this has changed. Not only has there been an explosion of media channels, but also recognition of that the dirtier a story is the better. This makes one wonder if all publicity is still considered good publicity.

Everywhere in society, individuals are being bombarded with advertising. Whether it is on the television, the radio, the Internet or big billboards on the streets, consumers cannot escape the messages companies are trying to force on them. Marketers are always trying to take this fight for consumers‟ attention to the next level. In this battle, having a strong brand can be a competitive advantage. According to Faircloth, Capella & Alford, (2001), a brand is one of the most impor-tant assets a company can possess. Therefore, one can understand the importance of a consumer with a favourable brand attitude. Brand attitude is the sum of the consumer‟s overall evaluation of the brand (Aaker, 1991) and can be influenced by different factors. It might be various keting messages about product attributes, point-of-purchase displays, packages and other mar-keting stimuli (Solomon, 2002).

Not all messages that reach the consumers are however controlled by the company. This can be considered as both an advantage and a disadvantage. With the rising costs of advertising, and the consumers‟ constant attempts to avoid ads, media coverage can be helpful in sustaining a strong brand. A study conducted by David Ogilvy, demonstrated that about six times as many people would rather read an article about a product than an ad for the same product (cited in Harris & Whalen, 2006). Theodore Lewitt (1969, p. 47) wrote in his book, The Marketing Mode, that “…when a message is delivered by a third party, such as a journalist or broadcaster, the message is delivered more

persuasively”. Publicity is simply considered being more credible as compared to advertising

(Har-ris & Whalen, 2006). Negative publicity in particular, is considered to have a stronger effect on brand images, mostly because of the negativity effect. It explains that negative information is perceived as being more diagnostic, and can say more about a product or company, than positive publicity can (e.g. Fiske, 1980; Skowronski & Carlston, 1987). Therefore, just as companies can enjoy the rewards positive publicity can bring, they can suffer the damages of negative publicity (Dean, 2004).

In fall 2003, an inspection of Skandia and its subsidiary company Skandia Liv created one of Sweden‟s worst corporate scandals (Olsson, 2004-02-05). It became public that the private cus-tomers of Skandia Liv had been neglected by internal affairs, where multibillion affairs had been made without any documentation. Furthermore, the inspection showed that not only had there

pense of Skandia, but also that the costs for two bonus programs were estimated to over two bil-lions SEK. The costs for these bonus programs should have been considerably less, but the pe-riod for one of the programs had been extended and the max limit for the other had been re-moved. This took place without the awareness or approval of the committee (Olsson, 2003-10-29). All of these events damaged Skandia‟s 150 years –old brand. The customer satisfaction level was prior to these events estimated, on an index of 0-100, to approximately 55. In the period be-tween fall 2003 and 2004, this had decreased to just above 40. The image of Skandia, and con-sumers‟ loyalty towards the company, were impaired the most (Eklöf, 2007-11-12).

In December 2007, another corporate scandal covered all front-pages in media. It was revealed that one of Sweden‟s most recognized grocery stores, ICA, was selling out-of-date meat. They re-labelled the out-of-date packages with a postponed expiration date, and sold to the customers. In addition, it turned out that old meat was used to make minced meat (Hernadi, 2007-12-06). Nor-dic Brand Academy did an attitude-investigation in order to see the effects of the scandal on ICA and their brand. The companies are judged on an index from 0-100. From being in top three with a score of 76.2, ICA fell to an index of 58.9. The scandal damaged the company‟s image (Nilsson, 2007-12-22). What is interesting though, is that, for the two last weeks in December 2007, the meat sales increased with 10-15 percent compared to the same period in 2006 (TT, 2008-01-09).

The examples illustrate how sensitive brands are. A company‟s image can truly be damaged by negative publicity. Both Skandia and ICA would probably have preferred that they were never exposed to the negative publicity. However, the outcome does not have to result in a bad way. It is up to the company to influence the outcome, both in the public opinion, and a company‟s credibility (Newsom, Turk & Kruckeberg, 2004). The degree to which consumers attitudes are changed due to negative publicity may differ depending on what actions the company takes to restore and preserve the brand image (Dawar & Pillutla, 2000).

Referring back to the cases with Skandia and ICA, they both dealt with their crises in different ways. The measures taken by Skandia, were to fire the whole board of management, and to ap-point a new CEO. They also performed an extensive analysis both internally and externally through independent investigations (Skandia, 2003-12-01). For the case of ICA, the company re-sponded quickly, and announced that the corporate group would take whatever necessary actions to make sure that such an event would never occur again. All of the 1400 stores would be certi-fied in provision management, and that an outsider part would inspect the stores‟ control pro-grams (TT, 2007-12-06). ICA was willing to take responsibility, and to minimize the damages as soon as possible by notifying the public about what was going on. Skandia was not prepared for this kind of situation they faced, and they acted accordingly. The scandal was revealed to the public in October 2003, however not until December 2003 did Skandia release a press statement with the arrangements they planned to take (Skandia, 2003-12-01).

The way in which these companies dealt with their situations affected the outcome of the nega-tive publicity exposure. In the case of ICA, the neganega-tive publicity was, through the actions taken by the company, turned into something positive in the end as their meat sales eventually in-creased (TT, 2008-01-09). The negative event of Skandia on the other hand, ended up in a tough situation with an outcome that was not in favour of their brand image. Leslie Gaines-Ross, Bur-son-Marstellers, an expert on companies‟ reputations and confidence, said ”It will take four years to

exculpate Skandia’s brand” (Resume, 2003-10-27).

If by responding strong, a company can attenuate the outcome of negative publicity, then maybe the saying “All publicity is good- except an obituary notice” is still valid after all. The two cases, Skandia and ICA, have indicated that this might be the case and the theoretical literature seems to sup-port this notion as well. Petty, Cacioppo and Schumann (1983), claim that strong corporate

re-sponses with well-built arguments have been proven more likely to result in positive attitudes than for a response containing relatively weaker arguments. However, this would assume that consumers would react to both negative publicity and corporate responses in a homogenous way, and that their change in brand attitudes would be determined by the way a company han-dles negative publicity. Studies done by for example Ahluwalia, Burnkrant and Unnava (2000), have proven the opposite. According to them, the consumer‟s level of commitment is a key de-terminant in the way individuals process negative information, and the outcome of it. They argue that the more committed a consumer is, the more likely he/she is to counter-argue negative in-formation, and be more resistant to attitude changes towards a brand that has been exposed to negative publicity. If this would be the case, then maybe consumers‟ level of commitment could also attenuate the effects of weak corporate responses.

1.2 Problem discussion

It is becoming more and more obvious that the brand is no longer in the control of marketers, but rather there has been a shift in balance in the direction of external parts. It is nowadays well known that consumers and the media have a great impact on how a brand is perceived. Fur-thermore, since the media has a tendency for reporting negative news over positive (Dennis & Merrill, 1996), it is more likely that companies will be exposed to negative publicity (Dean, 2004). In addition, with the continuous growth of the World Wide Web, it no longer exists boundaries that limit the extent publicity reaches out to the public. Companies are losing more and more control on what is said and spread about their products and brands. What can be learned from the cases of ICA and Skandia is that even strong and well established brands can be damaged by negative publicity. It takes a long time to create and develop strong brands but it takes only a short amount of time to destroy it.

A brand can however recover, but this will depend on the way in which companies decide to re-spond to the negative publicity. Millar and Heath (2004, p. 2) write, “Rere-spond well and survive the

cri-sis; respond poorly and suffer the death of the organization’s reputation and perhaps itself”. Controlling what is

said about a company is close to impossible. Learning how to deal with it is achievable.

Existing commitment literature has mainly focused on researching the commitment variable in the context of negative publicity, mostly because of the negativity effect, without taking other variables into account (e.g. Ahluwalia et al., 2000). However, corporate response is viewed as a critical element affecting the outcome of the negative publicity. The literature on corporate re-sponse has often been brought up in contexts of unknown brands (e.g. Dean, 2004). This be-cause there has been a main focus on understanding the effects of strong and weak corporate re-sponse, and less focus on the underlying factors to why for example strong corporate responses are perceived as strong. Accordingly, the authors believe that it would be interesting to investi-gate whether the commitment variable can influence the consumer reaction to corporate re-sponse, and what effect it might have in a negative publicity context. Is it possible that commit-ted consumers will be more resistant to attitude changes even in cases of weak corporate re-sponse? Does commitment even matter, or is the way a company responds to negative publicity of greater importance, in regards to consumers‟ attitude towards a brand?

With regards to this field of interest, this thesis will try to extend the current literature on nega-tive publicity, corporate response and commitment as well as further try to appreciate the value of a committed consumer to a company.

1.3 Purpose

The purpose of this study is to examine whether consumers‟ attitude towards a brand is changed depending on strong or weak corporate response to the negative publicity. A significant aspect is to investigate and further associate the commitment variable to the outcome of change in atti-tudes as a result of the negative publicity.

In order to fulfil the purpose, the following research questions will be addressed:

RQ 1: Is the consumers‟ brand attitude changed due to weak or strong corporate response? RQ 2: Is the consumers‟ reaction to the corporate response influenced by their level of commit-ment towards the brand?

1.4 Delimitations

There are several variables that are expected to have an impact on consumers‟ attitude towards a brand. However, this research is only focusing on the variable/covariate of commitment and how this is related to consumers‟ attitude in a context of negative publicity that is addressed by corpo-rate response. Further, there is no intention of scrutinizing the underlying rationale for the con-dition of commitment. In other words, there is no interest in examining why consumers are committed. The interest lies in the aspect of to which degree commitment matters in relation to negative publicity and corporate response.

Other delimitations have been made concerning the choice of data gathering for the experiment and hypothesis testing. The sample has been delimited both geographically and demographically since the target was for university students at Jönköping International Business School. The sample is intended to represent a population of consumers in Sweden between the ages of 18-30 as that was the age range for people taking part in the experiment.

1.5 Disposition

Chapter 1- Introduction

Chapter 2- Frame of Refer-ence

Chapter 3- Hypotheses

Chapter 4- Method

Chapter 5- Analysis

Chapter 6- Conclusion

In this chapter, an introduction to the subject is pro-vided, followed by the problem the authors have ob-served. The reader will hence get an insight into the subject, before getting introduced to the purpose of the study and research questions.

This chapter presents the reader with an overview of the theories and studies made within the fields of: Atti-tude towards brands, negative publicity, corporate re-sponse and commitment. This frame of reference will later support the analysis of the empirical findings through the use of SPSS.

This chapter clarifies to the reader which hypotheses are to be tested. The hypotheses are derived from the theoretical foundation presented in the frame of refer-ence section, within the field of negative publicity, negativity effect, corporate response, level of com-mitment, and brand attitudes.

In this chapter, the authors explain how they have gone about collecting information about the subject, and how the empirical findings have been reached. The procedure is described in detail, allowing the reader to be able to follow the discussion. The chapter is concluded with a discussion of the study‟s reliability and validity. Furthermore, a subchapter is devoted to describe in detail, how the authors have gone about when receiving the empirical findings through the use of SPSS.

This chapter describes the hypotheses testing, whether the stated hypotheses are to be accepted or rejected. It is followed by an analysis of the results, where a con-nection is drawn to the frame of reference.

In this chapter, the conclusions drawn from the study are presented, followed by a critique of the study and method, and suggestions to further research.

2

Frame of Reference

This chapter presents the reader with an overview of the theories and studies made within the fields of: Attitude towards brands, negative publicity, corporate response and commitment. This frame of reference will later support the analysis of the empirical findings through the use of SPSS.

The purpose of this study involves investigating the effects of negative publicity and corporate response on consumers‟ attitude towards brand. Therefore, the theory on brand and brand atti-tude are presented. It is important to understand how they are defined in the theoretical litera-ture and to comprehend the meaning of brand attitude, as it is the effects on this topic that will be measured. Furthermore, it is necessary to recognize what can influence consumers‟ attitude towards a brand and what this might depend on, as this will help clear any questions raised in the analysis. Therefore, the ABC-model and the functionality theory will be presented in order to shed some light on these fields of interest.

The two contrasting purchasing behaviours, high and low involvement, are depicted in order to explain the authors‟ choice of a high-involvement product in the research experiment (further clarified in chapter 4). A purchase is highly involving if the consumer is likely to carry out exten-sive evaluation, where the attributes that are highly weighted by the consumer will influence the formation of his/her brand attitude. A typical low-involvement situation on the other hand, is a repeat purchase and a habitual behaviour that does not require the formation of brand attitude. In order to conduct an experiment where the effects of negative publicity and corporate re-sponse on brand attitude are measured, the respondents are acquired to be highly involved and have formed a brand attitude toward the chosen product. The choice of a low-involvement product is therefore redundant, but explained for the sake of clarification.

The interest in negative publicity and corporate response lies in the fact that they are assumed to have an influence on consumers‟ attitude towards brand. It is therefore of importance to discuss what previous research argue about these two areas, in order to get a deeper understanding of how and why they can have an impact on consumers and their attitude towards a brand.

The role of the commitment variable in this research is based on the outcome effect and its moderating role of influencing consumer behaviour. The particular interest lies in the aspect of which degree it will affect consumers‟ attitude towards brand when exposed to negative publicity and whether it will have a potential change in their brand attitude. As the research questions in-volves investigating if commitment can influence the outcome of corporate response, prior stud-ies within the commitment literature will act as a foundation when explaining the findings in the analysis and conclusion. Hence, the theory presented constitutes a central framework supporting the view of commitment as a significant and interesting variable when studying consumer prefer-ences, attitudes and corporate response to negative information.

The theory on negative publicity, corporate response and commitment are important parameters when developing hypotheses, and are determining factors for the analysis and conclusion.

2.1 What is a Brand?

One of the most important professional aspects for marketers is their ability to create, maintain, protect and even enhance the brands of their products and services. Usually brands are defined from a managerial point of view, providing insufficient knowledge on what a brands means to the consumers. De Chernatony and Riley (1998) developed a theory of the brand by presenting a broad range of brand definitions. According to Bengtsson (2002) a brand can be described as a legal instrument, a logo, a company, a shorthand, a risk reducer, an identity system, an image in the consumers‟ minds, a value system, a personality, a relationship, and growing entity.

There are several definitions of a brand, each emphasizing different aspects of its meaning. One traditional definition of the brand is stated by Aaker (1991), where brand is a:

“…distinguishing name and/or symbol (such as a logo, trademark, or package design) intended to identify the goods or services of either one seller or group of sellers, and to differentiate those goods or services from those of com-petitors” (Aaker, 1991, p. 7).

In this definition the role of the brand is to create an object that stands out in front of its com-petitors, focusing more on the strategic activities of branding, disregarding that the consumers are the targets for the brand building activities. A similar definition is given by Keller (1998), also focusing on the brand‟s ability to differentiate between two products:

“A brand is a product, then, but one that adds other dimensions to differentiate it in some way from other prod-ucts designed to satisfy the same need” (Keller, 1998, p. 4).

Even if this definition might seem right from a managerial perspective where the aim is to build brands that are identifiable and yet different from competing brands, nonetheless the role of the brand for the consumer needs to be seen in a different way. As Heilbrunn (1999) points out it should also define the meaning of consumption, and the consumer‟s reason for consuming the brand for what it may bring:

“A brand may be viewed not solely as a sign added to products to differentiate them from competing goods, but as a semiotic engine whose function is to constantly produce meaning and values” (cited in Bengtsson, 2002, p.

18).

Brand and products are in a sense not only endorsed to satisfy consumer needs, but they are also consumed for the meaning they bring to a consumer‟s life. By understanding what makes the term „brand‟ meaningful for the consumer, it is easier to conclude which elements build up the notion of a brand (Bengtsson, 2002).

As Bengtsson (2002) further explains when the consumers recognize brands that they are famil-iar with, a number of elements besides the brand name constitute their experience of the brand. The consumer‟s experience might be equally, if not more, affected by visual elements such as lo-gotypes and package design, as the brand name itself. There is a close relationship between the brand and its endorsed products. In some aspects the product is considered to be a dimension of the brand (Kapferer 1997; Melin 1997) on the other hand the brand can also be a dimension of the product. Consumers might look for a specific kind of product that is available under differ-ent brands, e.g. shampoo which is available under differdiffer-ent brands, and any of the available brands can be considered adequate. In this case the brand is considered to be a dimension of the product and the brand can work as an attribute. In other cases the brand can be of high impor-tance to the consumer and the product becomes a dimension of the brand. In other words, what value consumers put into the word „brand‟ can be everything from physical entities such as products, to abstract elements such as meanings.

2.2 Attitude

Attitude is an abstraction that has no one absolute meaning or definition. Nevertheless the most widely used definition is formed by Allport (1954) who describes attitude as:

“A mental and neural state of readiness, organized through experience, exerting a directive or dynamic influence upon the individual’s response to all objects and situations with which it is related” (cited in Williams, 1992, p

98)

Attitude is also described as a durable organization of motivational, emotional, perceptual, and cognitive processes with respect to some aspect of the individual‟s world (Krech & Crutchfield, 1948).

These definitions provide the following main characteristics of attitudes:

Attitudes are related to a person or an object that is part of the individual‟s environment. To some extent, they form the way the individual perceives and reacts to this environ-ment, and the way we extract information from the environment. Ultimately they are motivational by affecting our perception of the goals we strive for.

Attitudes are learned and are relatively enduring. They can change, but usually not rap-idly.

They involve evaluation and feeling (Williams, 1992).

2.2.1 The ABC Model of Attitudes

An attitude is composed of three components: Affect, behaviour and cognition (the ABC model of attitudes). Solomon (2002) explains that affect refers to the way a consumer feels about an atti-tude object. Behaviour entails the person‟s intention to do something in regards to the attiatti-tude ob-ject, and cognition refers to the beliefs a consumer has about an attitude object. The aim of this model is to emphasize the interrelationship between knowing, feeling and doing. Therefore, a consumer‟s attitude towards a product cannot be determined by merely looking at their belief about the product. Although researchers traditionally believed that attitudes were formed in a fixed sequence of cognition, followed by affect and behaviour, it has also been proven that de-pending on the consumer‟s level of involvement and circumstances, attitudes can be formed from other hierarchies of effects as well (Solomon, 2002).

2.2.1.1 Hierarchies of Effects

The above mentioned components are all important, but their importance will vary depending on a consumer‟s level of motivation with regards to the attitude object. The concept of the hier-archy of effects has been developed by researchers in the field of attitude to explain the relative

impact of the following three components (Solomon, 2002),which have been illustrated in figure

2.1:

The standard learning hierarchy describes how a consumer approaches a product decision as a

prob-lem-solving process, where the consumer first forms beliefs about a product by gathering knowl-edge (beliefs) regarding relevant attributes (Solomon, 2002). Then the consumer evaluates these beliefs and forms a feeling about the product (affect) (Erickson, Johansson & Chao, 1984). Eventually, based on this evaluation, the consumer engages in behaviour, such as buying the product or supporting the brand. This hierarchy assumes that a consumer is highly involved in making a purchase decision (Ray, 1973).

The low-involvement hierarchy describes a consumer who initially does not have a strong preference

for one brand over another, but acts on the basis of limited knowledge and later forms an evaluation only after the product has been purchased or used (Krugman, 1965). The attitude is formed through behavioural learning in which the consumer‟s choice is reinforced by good or bad experiences of the product after purchase. According to Solomon (2002) this hierarchy indi-cates that not all purchase decisions are carefully considered through assembled sets of product beliefs, which means that it is not always beneficial to carefully communicate information about product attributes as a marketer. As consumers are not willing to gather and process complex brand-related information, they will instead be swayed by principal behaviour-learning such as responses caused by conditioned brand names, point-of-purchase displays, packages and other marketing stimuli.

The experimental hierarchy depicts consumers who act on the basis of their emotional reactions.

Solomon (2002) explains that this aspect highlights the idea that attitudes can be strongly influ-enced by intangible product attributes such as package design in combination with consumer‟s reaction to accompanying stimuli such as brand name, advertising, and the setting in which the experience occurs. Research indicates that the mood a person is in, when being exposed to a marketing message, influences how the message is processed, to what degree the information presented will be remembered, and how the person will feel about the item and related products in the future (Aylesworth & MacKenzie, 1998; Lee & Sternthal, 1999; Barone, Miniard & Ro-meo, 2000; Aaker & Williams, 1998).

Figure 2.1- Three Hierarchies of Effects (Solomon, 2002)

2.2.2 The functionality theory

In addition to the above mentioned components, it is important to understand the reasons for why people hold on to particular attitudes. As a matter a fact, the key to attitude formation is the function the attitude plays for the consumer. The functionality theory, which claims that attitudes ex-ist because they serve a function for the individual, was developed by psychologex-ist Daniel Katz.

Low-Involvement Hierarchy: ATTITUDE Based on be-havioural learning processing

Beliefs Behaviour Affect

Beliefs

Standard Learning Hierarchy:

ATTITUDE Based on cognitive in-formation processing Affect Behaviour ATTITUDE Based on he-donic con-sumption Beliefs Behaviour Affect Experimental Hierarchy:

The following are four attitude functions as identified by Katz (1960):

The utilitarian function (also known as instrumental or adjustive function): This function is related to the

basic principles of reward and punishment, implying that consumers develop attitudes towards products, based on whether the products provide pleasure or pain. As a result, people gain atti-tudes that are perceived as being helpful in achieving desired or avoiding undesired goals (Katz, 1960).

The Ego-defensive function: The ego-defensive function embodies the attitudes that are formed to

protect the person from external threats or internal feelings. In a sense, this allows people to avoid acknowledging their deficiencies. Attitudes of negative prejudice help the individual main-tain a sense of superiority over others in order to susmain-tain his or her self-concept (Katz, 1960).

The value-expressive function: This function expresses the consumer‟s central values or self concept.

A person forms an attitude towards a product not based on its objective benefits, but because of what the product says and expresses about him/her as a person. These attitudes are highly rele-vant to lifestyle analysis, which investigate how consumers develop a cluster of activities, inter-ests, and opinions to express a particular social identity (Katz, 1960).

The Knowledge function: Some attitudes are formed as a result of a need for order, structure or

meaning; and occur often when a person is in an ambiguous situation or confronted with a new product. Katz (1960) further argues that knowledge is gathered and sought in order to give meaning to what would otherwise be perceived as an unorganized and chaotic universe.

2.2.3 The impact of brand attitude and brand image on brand equity

Brands have for many years been part of the marketing scene, but lately the future of brands has been questioned (Light, 1994). As a consequence, researchers have focused their efforts on de-veloping a deeper understanding of how strong brands can be created and nurtured to avoid death of brands. Hence, to overcome the brand challenges, researchers and marketers have iden-tified a role for the brand equity construct. Although brand equity has been proposed as a finan-cial instrument for capturing and measuring brand value, marketers need to enhance the manage-rial aspects of brand equity to cope with the threats to their brand; and avoid managemanage-rial failure which will lead to the loss of one of the firm‟s most vital assets (Faircloth et al. 2001).

Brand equity has been defined by the Marketing Science Institute (Baldinger, 1989) as a financial asset as well as a set of favourable associations and behaviours. Farquhar (1989) describes that brand equity to a consumer is the result from a positive evaluation, or attitude towards the branded product. Brand equity can according to Keller (1993) also result from the consumer‟s brand knowledge memory structure, which in turn is composed of brand image and brand awareness.

Brand image is made up of the perceptual beliefs about a brand‟s attributes and attitude associa-tions; these two elements are in turn often seen as the basis for an overall evaluation of, or atti-tude, towards a brand. Brand attributes are the tangible and intangible features and the physical characteristics of the brand (Keller, 1993). In some respect, brand image is formed from the as-sociations related to the brand, while brand attitude is the sum of the consumer‟s overall evalua-tion of the brand. Brand associaevalua-tions are the linked memories a consumer has to the brand (Aaker, 1991). Faircloth et al. (2001) simplify these expressions even further by describing brand equity as the biased consumer actions towards an object, brand image as the perceptions related to the object, and finally brand attitude as the evaluation of the object.

As brand image is considered to be the combined effect of brand associations (Biel, 1992), it is an important element of brand equity. Research has proven (Krishnan, 1996) that high equity

brands have more positive brand associations and thereby more brand image, than for low equity brands. In addition, positive brand image is more likely to be connected with preferred brands than non-preferred brands (Kwon, 1990). The positive brand image triggers an associative mem-ory network of the brand, which in turn affects consumer decision making, which in the end contributes to brand equity. The research conducted by Faircloth et al. (2001) reveals that brand image did indeed directly influence brand equity. In addition they concluded that brand attitude, as being a type of brand association and a part of brand image, had an indirect effect on im-proved brand equity. Brand equity can therefore be manipulated by providing brand associations and signals to consumers, which will result in images and attitudes that influence brand equity. Conclusively, investment in image focused marketing and brand building is beneficial and can ul-timately lead to enhanced brand equity. As Faircloth et al. (2001) point out, brand equity should not be considered as a balance sheet asset; even if this provides valuable measurements for the marketer, it does on the other hand, not provide guidance for creation of brand equity. Firms are encouraged to create brand images that have been developed and proved to have positive brand equity effects, while marketers should manage brand image and brand attitude, and not brand equity. In addition, Faircloth et al. (2001) emphasize that marketers should create and manage positive brand attitudes as one of the brand associations which through synergy creates the de-sired brand image.

2.3 Levels of involvement

As the supply of products increase, it becomes even more important for consumers to evaluate the available brands in each product category. Even if brands in general may be perceived as similar, it does not automatically mean that they will be equally preferred. Jobber (2007) explains that the reason is that consumers make preference and similarity judgments based on different product attributes. The extent to which consumers evaluate a brand is expressed as their level of

involvement, which is defined as the degree of perceived relevance and personal importance

com-plementing the choice of brand.

The consumer is likely to carry out extensive evaluation, if a purchase is highly involving. Jobber (2007) further clarifies that high-involvement purchases generally include purchases with high expenditure or personal risk, such as buying a house or a car. Low-involvement purchases are the opposite and require simple evaluations about purchases.

The two involvement situations, as shown in figure 2.2, call for different evaluative processes where the high-involvement purchase behaviour is described by the Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) theory of reasoned action, and the low-involvement situation with the simple decision making process which has been best depicted by Ehrenberg and Goodhart (1980).

The Ajzen and Fishbein model (1980) proposes that an attitude towards a brand consists of a set of beliefs about the brands attributes, which are the perceived outcome that result from buying the brand. The attributes that are highly weighted by the consumer will have a large influence on the formation of brand attitude, which constitutes the consumer‟s overall impression and evalua-tion of the brand. The evaluaevalua-tion of the brand is not limited to personal beliefs of the brand, but it is also affected by outside influences, such as the opinions of important others in regard to the purchase of the brand. Conclusively, consumers are highly involved in the purchase to the extent that they evaluate the consequence of the purchase and the opinion of others in regards to it. The Ehrenberg and Goodhart model (1980) explains that a typical low-involvement situation is a repeat purchase of fast moving consumer goods. In this case awareness precedes trial and if it is satisfactory, it will lead to repeat purchase. In a sense, the behaviour becomes habitual and does

importance of the purchase is limited, it does not necessitate the evaluation of alternatives as suggested in the Ajzen and Fishbein model (1980). Awareness precedes behaviour, behaviour precedes attitude, and the consumer is passive and does not actively seek information. As a re-sult, any of the several available brands may be considered adequate.

Figure 2.2- Evaluation and Purchase Models (Jobber, 2007)

2.4 Negative publicity

Negative publicity is defined as “…the non-compensated dissemination of potentially damaging information

by presenting disparaging news about a product, service business unit, or individual in print or broadcast media or by word-of-mouth” (Reidenbach, Festervand & MacWilliam, 1987, p. 9).

A company or a product can suffer from negative publicity. It can be directly through a media exposure about a product defect, or indirectly by making unfavourable aspects about a company, such as social or ethical questions, public (Weinberger, Allen & Dillon, 1981; Veiga & Matos, 2005). Negative publicity can have damaging effects on a corporate image if not managed cor-rectly (Dean, 2004).

Reidenbach et al. (1987) have identified four possible effects publicity can have on companies. According to the authors, the consumers can have favourable (unfavourable) attitude towards the company, and an unfavourable (favourable) attitude towards the product. The first effect is where the company receives positive publicity, and the public has a positive attitude towards both the company and the product. The second is where the company has been exposed to nega-tive publicity, and the public has thus a posinega-tive image towards the product but not towards the company. The consequences of the negative publicity about the company can result in decrease in product sales, even though no product defect was involved in the negative publicity. The third effect is when the product receives the negative publicity. The effects on the company image in this case are, according to Reidenbach et al. (1987), not severe. The reasons behind this effect are that the public expects some product related problems along with beliefs that the company will handle the issue in a correct way. Therefore, the company will not receive a negative image from

Subjective norms

Low involvement: Ehrenberg and Goodhart repeat purchase model

Awareness Trial Repeat

pur-chase Normative

beliefs

Purchase

intentions Purchase

High involvement: Azjen and Fishbein model of reasoned action

Personal

the public. The fourth and last effect is when both the product and the company receive negative publicity, and hence the image for both is negative. In this situation, the negative publicity origi-nates from a product defect, and the way the company has handled the situation has resulted in a negative image for the company as well (Reidenbach et al., 1987).

What has profoundly been observed and demonstrated in the theoretical literature when discuss-ing negative information and the effects of it is the negativity effect (Ahluwalia et al., 2000). The advocates of this theory say that when individuals are exposed to negative information, it will re-ceive more weight than positive information (Fiske, 1980; Skowronski & Carlston, 1987; Mahes-waran & Meyers-Levy, 1990). The explanation for this is that the negative information is per-ceived as being more diagnostic for classifying objects in categories (Maheswaran & Meyers-Levy, 1990; Skowronski & Carlston, 1987). Negative information can hence say more about a product, than positive or neutral information can. For example, if a product is exposed to nega-tive publicity, the consumer can categorize it as being poor in quality. Posinega-tive or neutral infor-mation on the other hand, would not have helped them to categorize it, since one expects that products will have such qualities (Herr, Kardes & Kim, 1991). Negative information is more in-formative and diagnostic for the consumer in the decision making process, and hence, is given more weight (Ahluwalia et al., 2000).

What has so far been discussed and assumed is that consumers react to negative information in a homogenous way. However, studies have shown that there are factors that can moderate the im-pact of the negativity effect on consumers (Ahluwalia et al., 2000). For example, it has been shown that individuals‟ prior attitudes and beliefs will influence the effect of negative informa-tion. If the negative information is in accordance with the receiver‟s prior beliefs, it will just con-firm what the receiver believed. Hence, the negative information will be accepted. (Sherif, Sherif & Nebergall, 1965; Edwards & Smith, 1996). Conflicting information, on the other hand, will be examined more thoroughly, and attempts will be made to undermine that information (Edwards & Smith, 1996).

Ahluwalia (2002) has in a study investigated whether brand familiarity and involvement can in-fluence the negativity effect. The study demonstrated that when consumers are familiar with a brand and have a positive attitude towards it, they are more likely to counter-argue the negative information. They will perceive the information as being less negative and try to defend their at-titudes, compared to consumers who are not familiar with the brand. The consumers will hence put more weight on the positive information, since it is consistent with their attitudes. Positive information is thus perceived as being more diagnostic (Ahluwalia, 2002).

2.5 Corporate Response to Negative Publicity

The unexpected is never expected. In the area of marketing, if the unexpected event is impera-tive enough, it can lead to devastating declines in market share, loss of public trustworthiness, and major losses in profit. The corporate image is in that sense essential to all organizations and is further a central concept in the field of public relations (Moffitt, 1994).

An organizational crisis is suggested to be defined as: “A threat to high-priority values of the

organiza-tion, (2) which present a restricted amount of time in which a response can be made, and (3) be unexpected or un-anticipated by the organization” (Hermann, 1963, p.64).

Crisis research addressing various marketing issues is viewed to be fairly limited, especially con-cerning effects of different corporate responses on critical marketing variables (Dawar, 1998). Yet, there exists some research dealing with this issue. According to a study conducted by the

nificant purchase influence (after product quality and handling of complaints (Dawar & Pillutla, 2000). However, even if a crisis calls into question the future success or existence of an organiza-tion, the crisis can lead to either positive or negative organizational outcome depending on ac-tions taken (Marcus & Goodman, 1991) When it comes to corporate crisis derived from negative publicity, corporate response can therefore be argued to constitute a decisive factor influencing consumer attitude towards the company and the brand. Once the negative company-related inci-dents have occurred, they have the great potential of both directly and indirectly affecting large numbers of people. If the company is blamed for a serious negative incident, the brand equity and customer loyalty may drop rapidly (Jorgensen, 1994). Nevertheless, the degree to which con-sumers attitudes are changed due to negative publicity may differ depending on what actions the company takes to restore and preserve the brand image. For that reason, corporate response could be argued to constitute a vital tool for decreasing the potential impact the negative public-ity may have on consumers‟ attitude towards the brand.

When consumers are unexpectedly presented with highly negative information or company-related disasters, they are very likely to respond by first trying to understand the cause of the in-cident, and search for explanations for the occurrence (Weiner, 1986). Consumers are however rarely provided access to first-hand information about company-related incidents, which give them no choice but to rely on third party sources such as the media or company representatives (Weiner, 1986). The interesting matter is then how consumers react to given explanations, if there are at all any explanations presented.

Results of an experiment designed by Menon, Jewell & Unnava (1999) showed that strong cor-porate response and arguments caused less damage to the brand attitude when faced with nega-tive publicity. Conversely, no-comment responses as well as weak argument conditions indicated higher damage to the brand image. Consequently, this experiment provided the basis for the no-tion that high corporate response can make a significant difference in the outcome effect of negative publicity. In other words, strong arguments are more likely to result in positive attitudes, than for a response containing comparatively weaker arguments (Petty et al, 1983). What is im-portant to keep in mind though, is that the consumer perceptions are far more imim-portant than the actual reality. The central point is not whether the business in fact is responsible for the nega-tive act, but whether the firm is thought to be responsible for it by the audience. Certainly, if the firm is not to blame for the act, this can be an important module of the corporate response. Nonetheless, as long as the audience perceives the firm to be at blame, the brand image is threat-ened (Benoit, 1997).

The way in which a company manages this corporate response with intention to influence the consumers‟ attitude is in the literature referred to as „Impression Management‟. More explicitly, it relates to the process by which people, or in this case companies, control others‟ impressions of them (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). Schlenker (1980) argues that impression management can be es-pecially important in response to serious negative events.

In relation to Impression Management, a company‟s response can take multiple forms. In prac-tice, corporate response to crisis varies from stonewalling to support-communication and un-conditional product recall (Dawar & Pillutla, 2000). Stonewalling refers to a denial of responsibil-ity and absence of corrective measures or no communication at all, whereas the support com-munication refers to a statement of responsibility. This usually entails some kind of apology to consumers along with some sort of remedy such as product recall or free replacement. Most cases usually fall somewhere in-between these “extremes”. For instance, a company may express that corrective action is to be taken, but states no responsibility taking, extended apology or product recall (Dawar & Pillutla, 2000). Besides responding directly, firms can thus to some ex-tent restrict and control information that is harmful to their reputation by selecting appropriate response strategy. The strategy to not respond at all for a company facing negative publicity is

particularly chosen when the company cannot refute the publicized information. Consumer reac-tion to this lack of response informareac-tion appears to be an increased desire for whatever informa-tion available (Worchel, 1992). Hence, the company should preferably give some kind of re-sponse and, as referred to the crisis management literature, „tell their own story‟ (Meyers & Ho-lusha, 1986). In other words, management is advised to give its own explanation for what caused the incident. Often, more than one factor may be potentially responsible for a particular incident

2.6 Brand Commitment

Marketers are nowadays well familiar with the fact that keeping an existing customer is ordinarily less costly than acquiring new ones. Accordingly, factors determining consumers‟ decision whether to stay or exit a brand relationship has become a focal point in business marketing. These factors of loyalty in a brand relationship are to be dependent upon a range of variables where the term brand commitment is viewed to function as a significant variable, potentially affect-ing the outcome of negative information in this brand-attitude context (Sekar & Unnava, 2001).

2.6.1 Brand Commitment and Brand Loyalty

As numerous researchers have stated, brand commitment is a vital paradigm of the relationship-marketing theory (Dwyer, Schurr, & Oh, 1987; Morgan & Hunt, 1994) The term commitment is according to Kiesler (1971) defined as “the psychological attachment” (cited in Ahluwalia, 2001, p.458) and is further viewed as a close antecedents to behavioural loyalty (Beatty, Sharon, Kahle & Homer, 1988). Brand commitment is thus observed as closely related to the term of brand loyalty, and authors have even suggested the two constructs to be the same (Assael, 1998). How-ever, recently, researchers hold the view that the interrelation between the two constructs should not be interpreted as the same variable but distinct ones, although related (e.g. Ahluwalia et al., 2001; Beatty et al., 1988; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Researchers have suggested brand commitment to be an attitudinal element of brand loyalty where the definition of brand loyalty could be de-fined as “repeat buying, or experiencing the offering combined with a positive attitude” (Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978, cited in Arantola, 2000, p.8). Relationship commitment on the other hand, is defined as “behavioural and attitudinal state of the member based on experience and including intentions to act in the future” (Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978, cited in Arantola, 2000, p.8).

Additionally, Robertson (1976, p.19) offers a definition of commitment in the particular con-sumer behaviour context as “the strength of the individual's belief system with regard to a product or a

brand.” The larger the number of distinctive attributes and more prominent they are, the greater

the commitment.

2.6.2 Outcome of commitment

The interest in the commitment variable has often been related to the outcome effect and its moderating role of influencing consumer behaviour. More specifically, the outcome effect for this study concerns the aspect to which degree it will affect consumer response to negative pub-licity and a potential change towards brand attitude. This interest paradigm derives from prior studies stating for instance that commitment is strongly related to resistance to change (e.g. Ahluwalia et al., 2001). Kiesler and Sakumura (1966, p. 349) argue that “the effect of commitment is to

make an act less changeable”. Further, numerous studies support the conception that resistance to

change increases along with the higher degree of commitment (e.g. Halverson & Pallak, 1978; Kiesler & Sakumura, 1966). Even though the term resistance is argued to also be positively associ-ated with other variables such as the attitude centrality (Rokeach, 1960) and the level of position

involvement (Freedman, 1964), resistance to change is yet an important association with the variable of commitment which is further discussed in the following subsection.

2.6.3 Resistance to change

Commitment effects have been studied in various relation contexts. Social psychologists have in-voked notions to explain why attitudes may be resistant to change. The commitment variable has for instance been linked to adversity and interpersonal relations, where adversity refers to negative experience resulting in lower satisfaction with a relationship. Studies of this field have shown that people highly committed to a person tend to consider an attractive alternative (person) less fa-vourable as a means of resisting change and maintaining their commitment in the original rela-tionship (Johnson & Rusbult, 1989). For instance, Johnson and Rusbult (1989) conducted a hy-pothesis testing of relationship commitment presenting the result that committed subjects, when confronted with a highly attractive potential alternative partner had inferior attitudes toward the alternative.

In marketing context, the issues of preference stability and commitment have, as previously men-tioned, been primarily discussed in association with brand loyalty but also with consumers‟ resis-tance to persuasive communication. The concepts used to explain these observations are in fact taken from social psychology. In the marketing literature however, recent work on commitment has corroborated the main outcome of resistance to change in the brand context (e.g. Ahluwalia et al., 2001; Pritchard, Havis & Howard, 1999). Previous studies have shown that highly brand-committed consumers resisted changing their attitudes towards the specific objective when deal-ing with negative publicity compared to low brand-committed consumers (Ahluwalia et al., 2000). For instance, the hypothesis for one study was that low commitment consumers would show greater attitude change in the negative information situation compared to positive informa-tion, whereas high commitment consumers were expected to react conversely. The results of the study were as expected. For the strongly committed consumers, negative information did not re-sult in a significant attitude change and thereby confirming that the higher degree of commit-ment, the more resistant is the attitude to change (Ahluwalia et al., 2000).

These theories generate a concluded assumption that commitment refers to a tendency to resist change in preference in response to conflicting information. It further provides sufficient sup-port to the idea that commitment is a characteristic variable that has potential to influence the outcome of negative publicity among consumers.

2.6.4 Constancy of Attitudes

Constancy refers to the durability of the attitude. More explicitly, while resistance to change refers

to the act of making the attitude more difficult to change when an influential or counter-attitudinal message is presented, constancy refers to the extent to which an attitude remains un-changed in spite of confronting messages (Krosnick & Petty, 1995). Given that commitment is expected to strengthen the related attitude, hypothetically, expectations would be to find the atti-tude created by committed consumers to be more constant in comparison to those non-committed consumers.

In the interpersonal relationship literature, constancy or stability of a relationship has been studied rather comprehensively. Empirical work within this field has acknowledged commitment as the strongest interpreter of constancy (Rusbult & Martz, 1995). These studies support the view that commitment increases the constancy of the related attitude. However, studies within the market-ing field are less extensive when it comes to persistence of attitudes associated with brand-commitment. Yet, some studies have been carried out. For instance, an exploratory study by

Fournier (1998) was based on in-depth interviews, with the objective to understand brand rela-tions in the consumer context. Some aspects of the findings support the idea that the existence of commitment results in more stable attitudes.

2.6.5 Counter-arguing communications

An explanation to why committed consumers are less likely to change their attitude towards a brand may be explained by means of counter-argumentation (Chen, Reardon, Rea, & Moore, 1992). Some researchers further suggest that highly committed consumers even counter-argue messages that are both exceedingly logic and convincing (Abelson, 1986). For that reason, the counter-arguing aspect can be viewed as one significant explanation to why committed consum-ers resist brand attitude change. Previous marketing studies thus reason this counter-arguing phenomenon to be the mediating variable between commitment and attitude change (Ahluwalia et al., 2000). For instance, in a recent study by Ahluwalia et al. (2000) committed consumers of the target brand, Nike, were recruited and exposed to negative publicity concerning the brand. The cognitive responses followed by the presented information were implied as counterargu-ments and supportive argucounterargu-ments defending the brand in its favour. The outcome of this study thus confirmed the notion that counterarguments mediate the effects of negative information on attitude change for committed consumers. In other words, consumers appear to defend and pro-tect their brand attitudes by counter-arguing communications when confronted with information that is inconsistent with their attitudes (Ahluwalia et al., 2000).

2.6.6 Information processing

In addition to the resistance to change-effect as an outcome of commitment, it has also been studied that the presence of commitment influences the information processing. The relationship be-tween commitment and information processing has for instance been discussed by Robertson (1976). He argues that influential communication is successful under low/non commitment con-ditions because there is little propensity to protect low/non commitment beliefs. Ahluwalia et al. (2000) further support the notion that commitment moderates the analytical and questioning in-clination of information. Accordingly, it is argued that selective processes are operational under high commitment conditions, and the influencing extent thus decreases with the higher com-mitment. In addition, the comprised literature by Ahluwalia et al. (2000) interestingly suggests that negative information has a higher degree of analytical tendency and as a result, consumers focus more on negative information than on such positive. Ahluwalia et al. (2000) further argues that high committed consumers are expected to counter-argue negative information to a larger extent than low committed consumers who find negative information more analytical.