Crisis Management &

Learning Processes

BACHELOR’S DEGREE PROJECT THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Marketing Management AUTHOR: Ella Meyner & Christine Yildiz

JÖNKÖPING April 2020

An exploratory study on internal crisis management

and implementation of learning processes within

nonprofit organizations

i

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Crisis Management & Learning Processes, An exploratory study on internal crisis

management and implementation of learning processes within nonprofit organizations.

Authors: Ella Meyner, Christine Yildiz Tutor: Katrine Sonnenschein

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Crisis Management, Learning Processes, Nonprofit Organizations, Humanitarian

Organizations, Money Collecting Organizations.

Abstract

Background

The existence and threat of crises are present in all environments, and the management of these is a key part of multiple companies’ communication strategies. In the media landscape of today, crises play a central role, and a badly managed crisis can lead to the end of an organization (Penrose, 2000).

Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of how organizations with generally less resources manage unpredictable negative events. This will be done by investigating how nonprofit organizations recognize the importance of implementing learning processes within internal crisis management.

Method

The primary data will be collected through interviews with five organizations within the nonprofit sector in Sweden. The research will allow an analysis of to what extent learning processes are implemented, and what is prioritized within crisis management and learning.

Findings

Throughout this study, it is discovered that organizations highly prioritize learning from a crisis, however, none of the organizations in the study follow a specific learning process. Furthermore, the internal relation to crisis management can differ greatly between the organizations depending on experience and resources.

ii

Acknowledgment

We would like to express special gratitude to the multiple individuals who have supported us throughout this thesis.

Firstly, this thesis would not have been able to be conducted without the participating interviewees. With this being said, sincere gratitude is expressed to all the organization included, Beata Fejer (Cancerfonden), Bo Wallenberg and Anders Mårtensson (Barnmissionen), Lasse Lähnn (Röda Korset), Liv Landell Major (Majblomman), and Maria

Berg (Barnen Framför Allt - Adoptioner, BFA).

Secondly, our tutor Katrine Sonnenschein has contributed with feedback and guidance that has resulted in valuable insights that have increased the overall quality of the thesis. For this, sincere gratefulness is expressed.

Lastly, gratitude to the seminar group is expressed for their comments and feedback during the meetings that have contributed to a higher research quality.

Jönköping, 18th of May 2020

iii

Table of content

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1. Problem ... 1 1.2. Purpose ... 2 1.3. Research Question ... 2 1.4. Delimitations ... 2 1.5. Definitions ... 3 1.6. List of Abbreviations ... 42.

Frame of Reference ... 5

2.1. Crisis management ... 5 2.1.1. Crisis ... 62.1.2. The Manager’s Role ... 7

2.2. Nonprofit organizations ... 8

2.3. Learning Processes ... 9

2.3.1. Double-Loop Learning ... 9

2.3.2. Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) ... 12

2.4. Research Gaps ... 14

4.

Method and Data ... 15

4.1. Research Design ... 15 4.2. Research Philosophy ... 16 4.3. Research Approach ... 17 4.4. Method ... 18 4.4.1. Literature Search ... 18 4.4.2. Sampling ... 19 4.4.3. Interviews ... 23

4.4.4. Analysis of qualitative data ... 25

4.5. Trustworthiness ... 27 4.5.1. Ethics ... 28

5.

Empirical Data ... 29

5.1. Interviews ... 29 5.2. Crisis Planning ... 29 5.3. Managing Crisis ... 30 5.4. Resources ... 34 5.5. Communication ... 35 5.6. Experience ... 386.

Analysis & Discussion ... 40

6.1. Crisis Planning ... 40

6.2. Managing Crisis ... 42

6.3. Resources ... 44

6.4. Communication ... 45

6.5. Experience ... 47

6.5.1. The Manager’s Role ... 49

7.

Conclusion ... 50

7.1. Practical Implications ... 51

7.1.1. Limitations ... 52

iv

8.

References ... 54

9.

Appendices ... 61

9.1. Appendix 1a Questions for Organizations, English ... 61

9.2. Appendix 1b Questions for Organizations, Swedish ... 62

9.3. Appendix 2 Quotes in Swedish ... 64

9.3.1. Quotes on Crisis Planning ... 64

9.3.2. Quotes on Managing Crisis ... 65

9.3.3. Quotes on Resources ... 66

9.3.4. Quotes on Communication ... 67

9.3.5. Quotes on Experience ... 68

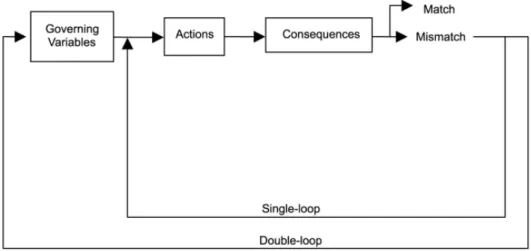

Figure 1- Illustration of Single and Double-Loop Learning ... 11

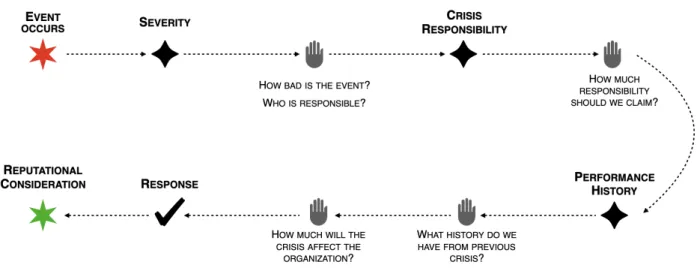

Figure 2- SCCT explained ... 13

Figure 3- Codes & Themes ... 26

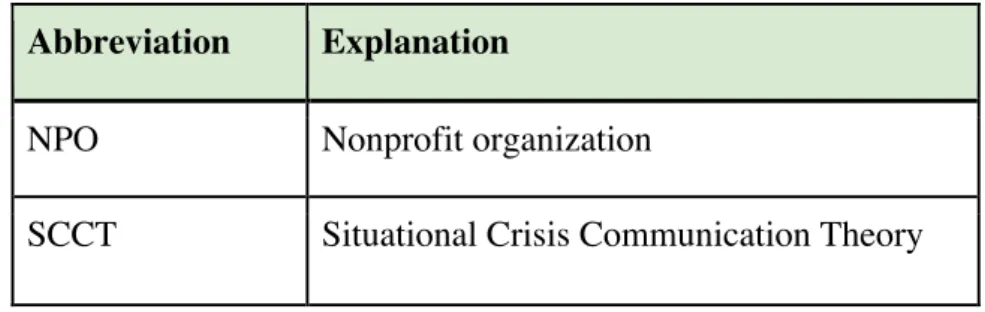

Table 1- Abbreviations ... 4

Table 2- Visual Overview of the Data Collection Process ... 19

1

1. Introduction

This chapter of the thesis includes a discussion of the chosen subject and definitions relevant to the study. Additionally, the purpose is stated as well as the delimitations of the research.

1.1. Problem

Due to the high standard to which the public holds nonprofit organizations (NPOs), the general perception is that an NPO is less likely to experience a crisis. However, the literature shows that the risk of a crisis is bigger for an NPO since they are extensively dependent on their stakeholders such as donors and volunteers. Nonprofit organizations also depend greatly on their reputation, and thereof the confidence of their stakeholders, and with the threat that an unmanaged crisis implies, one could assume that crisis management and resolvement would be highly prioritized, but the literature shows otherwise (Sisco, Collins & Zoch, 2010).

As Penrose (2000) explains, 40 percent of the biggest companies choose not to have a crisis communication plan. The reason for this is argued to lay within the belief that the company’s goodwill will protect them, or the confidence of the capital resources that the company obtain. However, when looking at smaller companies, these defense-opportunities seize to exist and reputation becomes a main asset (Penrose, 2000).

Furthermore, even though the NPO is not profit-driven, the financial state still affects it since it is strongly dependent on donations and investments. The loss of revenue would affect the company by, among others, forcing them to let employees go and reallocating resources (McVeigh, 2019). Meaning that an economic crisis could still occur within the organization, a significant challenge that NPOs face (Zhao, 2013). Moreover, an economic crisis within the NPO sector will affect the global economy through, not only unemployment but from a world trade and construction industry perspective, thus, NPOs are severely dependent on the global financial state as well. The NPOs play a vital role in the business environment, and they are equally likely to face a crisis as any other organization. However, they less frequently have a crisis management plan, and this is

2

argued to be due to limited resources (Bridgeland, McNaught, Reed & Dunkelman, 2009). By implementing learning processes, organizations are able to prevent the recurrence of a crisis. Learning processes enables a way of learning from internal events, but also from crises experienced by competitors, which creates a way of learning and handling crisis in a less costly way since it enables the organization to learn without the consequences of a crisis (Wang, 2008).

However, there is a lack of information about how a crisis can be foreseen from the manager’s perspective. Additionally, there is a lack of information about how an NPO learn from a crisis, and to what extent experience aid in conducting business decisions.

1.2. Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to investigate how NPOs recognize the importance of learning processes within crisis management. The research will be done within the context of NPOs since there is a gap in the literature lacking information about how an NPO learn from a crisis, and to what extent experience aid in conducting business decisions. The insights gained through this research will contribute to understanding the learning within NPOs in reference to two learning processes, Double-Loop Learning Theory and Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT).

1.3. Research Question

The gaps in the literature leads to the following research question;

How do nonprofit organizations recognize the importance of learning processes within crisis management?

1.4. Delimitations

The main limitation that will be carefully regarded is to only investigate nonprofit organizations, and that these are all within the humanitarian or money collecting sector

3

and located in Sweden. Multiple of the participant organizations have international operations, but the thesis will be focused on their internal crisis management that is carried out in Sweden. In order to broaden the participant spectra, a specific crisis has not been focused on, hence, the only denominator is that the crisis needs to be internal.

1.5. Definitions

Crisis - “A crisis is defined here as a significant threat to operations or reputations that

can have negative consequences if not handled properly” (Coombs, 2014).

Crisis management plan - “Crisis Management Plan refers to a detailed plan which

describes the various actions which need to be taken during critical situations or crisis” (Juneja, n.d).

Learning process - “A process that leads to change, which occurs as a result of

experience and increases the potential of improved performance and future learning” (Mayer & Clark, 2003).

Nonprofit organization - “Not-for-profit organizations are types of organizations that do

not earn profits for its owners. All of the money earned by or donated to a not-for-profit organization is used in pursuing the organization's objectives and keeping it running” (Kenton, 2019).

Humanitarian - “Humanitarian organizations help to ensure that there is swift, efficient

humanitarian assistance available when sudden natural disasters strike or wars occur or in connection with long-term conflicts” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, 2020).

Money collecting organization - Organizations that engage individuals or businesses to

make voluntary financial contributions to a specific cause (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d).

Stakeholders - “Stakeholders are any group that can affect or be affected by the behavior

4

1.6. List of Abbreviations

In the table below, the main abbreviations used throughout the study are displayed.

Table 1- Abbreviations

Abbreviation Explanation

NPO Nonprofit organization

SCCT Situational Crisis Communication Theory

5

2. Frame of Reference

This chapter includes an overview of the existing literature connected to the field of studies of this paper. This section will be divided into four main subheadings; crisis management, nonprofit organizations, learning processes, and research gaps.

2.1. Crisis management

In the field, the importance of having crisis management within the organizations differs. Since many managers argue that the possibility of a crisis occurring is not equally likely within every organization, some administrators have concluded that crisis management is unnecessary. Simultaneously, other experiences of crises show that a crisis could occur at any moment, which has made crisis management an essential part of these organizations (Spillan, 2003).

“Organizations that prepare for a crisis often employ the use of teams in developing a crisis management plan” (Dorn, 2000). Within a crisis management team, there are often people from different departments, this can range from senior administration to technical operations, but also public or consumer affairs, advertising, and public relations (Barton, 1993). The literature also highlights the importance of having a functional crisis management team. The team together with the organization are in charge of what issues and points need to be considered in the crisis management plan, however, this can be complicated as a result of having several members in the team. Potential issues connected to this can be how much experience and knowledge, or what attitude and motivation the member has, which then can affect structure and execution for the crisis management plan (King, 2002). However, several scholars have implied that having a mix of different individuals and include team-related factors can strengthen the efficiency and effectiveness of the crisis management team (Hirokawa and Keyton, 1995; Klimoski and Jones, 1995). Even if this may not be suitable every time, it is still recommended to have a more diverse group and there are also other factors that can enhance the effectiveness (Hirokawa and Keyton, 1995).

6

2.1.1. Crisis

Not everything that happens to a company is a crisis, hence, a crisis is defined as an event that generates negative and undesirable outcomes (Coombs, 2014). What several of the authors mention is that crisis can both be anticipated but at other times it can reveal itself with little or no warning at all (Spillan, 2003; Coombs & Holladay, 2002; Penrose, 2000). Mano (2010) mentions that the handling of a crisis greatly depends on the level of preparedness within the organization, which then can determine whether the organization survive the crisis or not. There are some components that a crisis needs to have in order to be defined as a crisis, it can either be all of the following or just a few of them. The first component is that the event has to disrupt the operations of the company, and the second one is that it leads to increased governmental regulation. The third and fourth components are connected to that the event creates a bad perception of the firm and/or creates a financial burden. The fifth component states that the event results in management spending their time on an unproductive task. Lastly, the sixth component is when the event results in decreased morale and support from the employees (Keown-McMullan, 1997). Keowon-McMullan (1997) also mentioned that a crisis has four stages; “the prodromal crisis stage; the acute crisis stage; the chronic crisis stage; and the crisis resolution stage”. The first stage, the prodromal crisis stage, is when the crisis is approaching but it is not possible to know when it will occur, hence, one needs to prepare for its occurrence. Secondly, the acute crisis stage is when the crisis has occurred, and the effort is prioritized into resolving the crisis as rapidly as possible while minimizing the damage of the organization. Following is the chronic crisis stage, this is after the crisis has been resolved where the emphasis is put on learning from the event, evaluating the weak parts of the organization, and developing the crisis management plan. Lastly, the crisis resolution stage is after the crisis has occurred, been resolved and the organization has recovered. This is the stage that the organization wants to reach since it implies full recovery or even improvement from the crisis (Keown-McMullan, 1997).

Another point that was stated in the literature is how nonprofits can be more exposed to a crisis compared to a for-profit enterprise since the organizations many times do not have the same resources. In addition, it was shown that some organizations believe that there is not enough time to focus on future crises since the resources need to be allocated to more imminent problems (Spillan, 2003). With this being said, one of the major threats

7

to an NPO is a betrayal of the public’s trust, due to it being one of the ground pillars within the NPOs operations (Sisco, 2012). Losing trust can be done over one single act but rebuilding it takes time (Hinn, 2012).

2.1.2. The Manager’s Role

There are multiple aspects that influence the outcome of a crisis, and it is crucial that the manager understands the situation in order to manage the crisis, and the manager’s perception is what determines the means used for the resolution (Spillan & Crandall, 2002). One other main factor is the crisis manager’s experience and capability to foresee a crisis, enabling efficient crisis resolvement. Furthermore, the history of previous crises within the company also affects the result of the occurring crisis, since the second crisis will affect the organization more than the first one (Sisco, Collins & Zoch, 2010). The crisis can be seen as both an opportunity or a threat, depending on the management’s perception of it, which influence the end result (Penrose, 2000). What Penrose (2000) state, is that there is a correlation between perceiving a crisis as an opportunity and the manager being more open to more diverse solutions, but also being more proactive in the actual planning before anything happens. This is since individuals think that opportunistic situations are more manageable and easier to handle, and if the manager perceives a crisis as a threat, this can restrict the viewpoints and intake of different information. In other words, perception can affect the manager’s willingness to participate in crisis management activities (Penrose, 2000). Besides the perception of an actual crisis, the manager’s perception of learning is equally as important. Mano (2010) states that depending on how a manager prioritizes a good learning climate this will also be noticed in how they perceive changes. Furthermore, stating that there is a linkage between openness to information for problem-solving and the level of crisis preparedness (Mano, 2010).

In previous literature, research shows that managers’ way of analyzing and responding to a crisis have an essential role in managing crises. In an environment where a crisis may occur, a leader has the obligation to make sure that all subordinates understands the situation, as well as make the potential response actions clear. By doing so, managers’ view of a crisis helps enable involved parties to take specific actions, which may aid the

8

organization. Previous literature also states that a manager taking action in a crisis enables personnel to work together despite having different responsibilities, or even operating at different locations (Kapucu, 2007). Additionally, the impact a manager has is dependent, to a high extent, on the information a manager possesses in regard to the situation. Furthermore, research shows that management can recognize signs of a crisis as well as appropriate measurement to prepare or prevent the crisis from happening by having the right information. The management readiness could also aid other stakeholders in coping with the uncomfortable environment following to the possibility of a crisis within an organization (Spillan, 2003). Research also shows that, by managers sharing information, and keeping their stakeholders constantly updated about the situation, they will show more compassion, which is a great advantage when resolving a crisis. Furthermore, it is becoming increasingly important for stakeholders to have a balance between their social and financial interests. Hence, it is nowadays almost equally important to be ethically considerate as it is to gain revenue (Coombs, 1999).

2.2. Nonprofit organizations

Nonprofit organizations exist for the public or common interest and this does not entail generating earning for any stakeholder. There are various types of NPOs and these can be anything from museums to hospitals or universities (Kearns, 1994). The general perception is that NPOs are less expected to find themselves in a crisis since the public holds the NPOs to a higher standard in relation to for-profit organizations. However, the risks are equally present for any organization, and the risk is arguably bigger for an NPO since they are extensively dependent on their stakeholders such as donors and volunteers. Furthermore, an NPO is not profit-driven, however, that does not mean that the economic state does not affect it since they are strongly dependent on donations and revenue (Sisco, Collins & Zoch, 2010). The findings from the literature show that nonprofit organizations are equally prone to experience a crisis as a for-profit company. However, only 60 percent of for-profit companies have a crisis management plan (Spillan & Crandall, 2002).

NPOs generally have fewer resources than similar for-profit organizations, although they have the same goals. In order for NPOs to deliver their message, they need to be more

9

creative with their communication strategies (Sisco, Collins & Zoch, 2010). In the literature, it is also mentioned that NPOs has a harder time handling a crisis due to fewer resources, but also less goodwill, hence, they need to prioritize where to allocate their resources, and in multiple organizations, crisis management is perceived to be a luxury that can not be afforded (Sisco, 2012). Furthermore, mentioned in the literature is that NPOs often tend to learn from other organizations’ mistakes, since that is a way of saving resources while still evolving operations (Coombs & Holladay, 2002).

2.3. Learning Processes

An important part of crisis communication is the multiple learning processes implemented as a part of companies’ crisis management plan (Wang, 2008). Learning processes are based on the assumption that managers learn from past experiences and implement these experiences in order to foresee and prevent future crises (Mano, 2010). In this study, two learning processes will be used as a guidance throughout the research, and these are Double-Loop Learning, and Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SSCT).

2.3.1. Double-Loop Learning

The Double-Loop Learning Theory is based on the concept of learning from a past crisis that evolved from an abrupt change in their environment and implementing the changes necessary for successful crisis management (Mano, 2010). When discussing the double-loop learning, one may link it to single-double-loop learning as well and for that reason it will be briefly explained. “One might say that participants in organizations are encouraged to learn to perform as long as the learning does not question the fundamental design, goals, and activities of their organizations” (Argyris, 1976), this is part of what the single-loop learning entails. Usually, when working with a task, feedback automatically comes from the surroundings, and this can both be positive or negative, but it informs whether the goal was achieved or not. Generally, in accordance with this feedback, the operation is often adapted to be more efficient, which is why it is called single-loop learning. The literature states that single-loop learning is most suitable in static and passive environments, however, most business environments are neither static nor passive (Tagg,

10

2010). This is the reason why authors often argue that double-loop learning is a more suitable way of learning since it focuses on more than just changing the objectives, it also includes questioning the assumptions (Cartwright, 2002).

Double-loop learning takes a deeper look into the norms and the structure that the organization has. With this learning process theory, the organization raises questions and looks at other alternatives and perceptions, but also other types of ways that the firm can address problems they have and could come across in the future (Cartwright, 2002; Mano, 2010). Argyris (1976) states that “the unilateral control that usually accompanies advocacy is rejected because the typical purpose of advocacy is to win; and so, articulateness and advocacy are coupled with an invitation to confront one another's views and to alter them, in order to produce the position that is based on the most complete valid information possible and to which participants can become internally committed”. What Argyris is implying is that only a skilled leader could accomplish what the double-loop learning entails. What is also highlighted about the double-loop model is how people and groups need to be open about changes in order to succeed, but this can mean questioning the basic way of how things are handled in the organization which is not something everyone are comfortable with (Argyris, 1976). Double-loop can be connected to how organizations evaluate and develop their communication and marketing activities. It also shows how important the manager’s openness and planning skills before a crisis occurs is. Furthermore, this model points out that there is a difference between routine problems and if an organization is considering where the problem occurred from and also understanding how to use the knowledge to future events. With this in mind, if the managers do not reflect and just do by routine, new knowledge that may be needed in order to develop effective strategies may not be seen (Blackman & Ritchie, 2008).

The difference between single and double-loop is further distinguished in Figure 1 by Argyris & Schön (1996). The main components of the models are Action, Consequences,

Match, Mismatch and for the double-loop Governing variables is added. Firstly, Action

is the step taken to manage the crisis. Secondly, the Consequences refers to the result of the action taken, these can be both expected and unexpected. Thirdly, the match and mismatch regard to the fact if the action was appropriate or not, if it is a match, the goal is reached. If the goal is not reached, it becomes a mismatch and the process starts over

11

with a new action. In the double-loop model, governing variables are added, and these are the variables that are considered when deciding an action since they will be affected by the decisions, and are also variables that impact the company (Anderson, 1997).

Figure 1- Illustration of Single and Double-Loop Learning

Source: Argyris & Schön (1996)

There are several researchers that have developed the double-loop learning model since Argyris created it in 1978, this has for example been done by McElroy (1999). His point of view is that many companies have already made a shift from single-loop learning to double-loop learning. He argues “learning when it moves, from simply performing to improving ‘how we do things’”, and when people not only reference rules, but also constructively challenge rote responses; they construct alternative scenarios to play out likely outcomes, test promising new ideas, and replace old rules if new approaches produce more successful outcomes in practice” (McElroy, 1999). This is something that Argyris & Schön (1996) agree upon, and also states that “double loop learning will promote inquiry, challenging current assumptions and actions and leading to new theories-in use”. McElroy (1999) further continues saying that this assumption is only correct if there is an ongoing challenge, however, there are no grounds to that this is correct. Earlier it has been stated that the double-loop process is challenging and tests learning throughout the business operations, however, it is argued that it is only done initially when a problem emerges (Blackman, Connelly & Henderson, 2004).

12

2.3.2. Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT)

Extensive research has been done in regard to the learning process named Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT), developed by Timothy Coombs year 2002. This theory is a common denominator between multiple articles, and the theory builds on attribution theory, hence, that individuals are driven to understand and control their environment. In the SCCT, one evaluates the crisis, the responsibility attributed to it, and then matches an appropriate crisis response. Additionally, SCCT connects the aspects that should be considered when deciding a crisis response, such as assumptions and relationships, to protect the organizational reputation (Munyon, Jenkins, Crook, Edwards & Harvey, 2019). The SCCT empowers organizations and managers in particular, with the tools to protect the organizational reputation impacted during a crisis. After categorizing the existing crisis in a fitting cluster, the manager can decide upon a calculated response action by choosing a crisis response strategy (Coombs & Holladay, 2002). In the utilization of the crisis response strategies, previous research indicates that in more than 90 percent of the cases, various combinations are used. Furthermore, when a single crisis response strategy was used, it was often described as ineffective (Kim, Avery & Lariscy, 2009).

Working with your reputation is stated by multiple authors to be important, hence, a reputation can be both positive and negative, and it is regarded as an intangible asset for the organization. In context, the reputational asset, can attract customers but also repel them, which can lead to future investment in the company or loss of revenue. When looking at NPOs, the reputational asset can create a competitive advantage (Bryson, 2004). “A reputation develops through the information stakeholders receive about the organization” (Fombrun & Van Riel, 2004). The information the stakeholders receive can be both firsthand and second hand, hence, it can be communicated from the organization directly to the public, or for example through the media. Most commonly, the stakeholders obtain a great part of the information from the media. This is why working closely with external communication is highly important (Coombs, 2007). Reichart (2003) states that stakeholders often compare similar organizations and their standards, and then form their opinion of the organization from a reputational standpoint. An expectation gap appears when an organization fails to meet the stakeholder expectation, which can lead to a negative impact on the reputation.

13

Figure 2 illustrates the components and flow of the SCCT model, developed by the authors in order to describe the theory as a whole. It starts with an event of some kind, and the first step is then to realize the severity. This is done by evaluating the severity of the event and also who carries the responsibility. It then comes to the question of responsibility, hence, how much responsibility should the organization claim? This is depending on previous performance history, meaning that one evaluates what crisis has occurred before, and how much a new crisis would affect the organization. After evaluating these factors, a response is decided based on reputational consideration, which is the last step of the process when handling a crisis according to the SCCT (Coombs, 2004).

Figure 2- SCCT explained

Source: Developed by the Authors.

Previous research surrounding SCCT and crisis communication theories, in general, has put a lot of emphasis on the for-profit business environment, and the reputational impact of how crises affect nonprofit organizational has not been documented to the same extent. The neglection in the research area indicates a gap in the existing literature. Research has shown that there is a great importance of reputation as an asset for all organizations, and that is no different for NPOs. However, published literature regarding public relations practitioners states that organizations in the past, that have experienced a scandal or

14

reputational damage have been impacted negatively, where some never recovered (Hillary, Fussell & Sisco, 2012).

2.4. Research Gaps

To summarize, the main gaps found when reviewing the literature was that there is a lack of information about how an NPO learn from a crisis, and to what extent experience aid in making decisions. The existing literature is to a large part also written from a theoretical standpoint, currently, there are not many organizational examples used to further strengthen the arguments surrounding the theory. Furthermore, a gap exists in how NPOs regard to their risk of experiencing a crisis, and how they are reasoning about allocating their resources since they, in general, have fewer resources and therefore maybe less prone to prioritize crisis management. Additionally, there is a lack of information about what crisis signals can be foreseen from the manager’s perspective, and to what extent experience is relevant in the situation. Lastly, it is mentioned in the literature that organizations learn from other organizations, however, it is not stated how this is done.

15

4. Method and Data

This chapter describes the research design, research philosophy, and research approach that was used in this study. Furthermore, this chapter includes an overview of the data collection, sampling method, and the interviews along with an analysis of the qualitative data. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the trustworthiness and ethics of the research conducted.

4.1. Research Design

In order to conduct research and answer the research questions stated, there are four possible approaches. These approaches are descriptive, exploratory, explanatory, and evaluative design of the research. A descriptive research question starts with what, when, where, who or why, since the purpose of the question is to get a descriptive answer. Furthermore, an exploratory approach is an effective way of asking open-ended questions which will lead to a deeper understanding of the subject. There are multiple ways of conducting an exploratory study, where interviews are the most commonly used tool to collect data. Explanatory studies present a relationship between variables, hence, the purpose is to analyze a situation and by doing so, explain the connection between variables. Lastly, the evaluative study focuses on the effectiveness of an organizational strategy, policy, initiative, or process by analyzing the functionality of it (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2016). The research will be conducted from an exploratory standpoint since the aim of the thesis is to gain a deeper knowledge and obtain a deeper overall understanding of the topic. Additionally, by using an exploratory study, the aim is to understand the patterns and to identify ideas that arise throughout this process.

The methodology of a research is either qualitative, quantitative, or a mixture of both. Quantitative data is connected to numerical data, examples of this could be questionnaires, statistics or graphs, while qualitative data is described as data in a non-numeric form (Saunders et al., 2016; Collis & Hussey, 2014). However, Saunders et. al. (2016) emphasize that it might be necessary to have an open-ended question in a questionnaire, hence, a mixed method is sometimes considered. In this study, a qualitative approach will be used to collect data, and the primary data will be collected using interviews, which is a non-numeric form of data collection. The existing theories

16

surrounding learning processes will be put into perspective when connecting it to crisis management and thus investigate and modify theories already recognized (Saunders et al., 2016). As stated previously, the literature has not established any clear learning process specifically for NPOs, and this creates questions of how learning is implemented for organizations that are not profit-oriented. Therefore, qualitative research can be argued most suitable for this study since this study pursues to answer the research question by gathering data through observations and interviews by studying social phenomena (Dudovskiy, 2016).

4.2. Research Philosophy

Research philosophy is a way of guiding the process, and it is important to acknowledge philosophical assumptions when conducting the study since this helps to understand the area of research and guides the study (Creswell & Poth, 2018). These assumptions will be regarded through a research paradigm. A research paradigm is based on the assumptions of people, concerning their knowledge and personal views about the world. Furthermore, it becomes a tool to analyze and interpret concepts and results surrounding the research. When conducting the research there are different paradigms that need to be taken into consideration, which are interpretivism, pragmatism, and positivism. Positivism was founded on the idea that social reality is objective, it identifies the data collected in a qualitative way with propositions that then will be tested, based on theories. Interpretivism, however, was established based on the criticism of positivism. Interpretivism was created on the assumption that social reality is in our minds, and therefore subjective and investigable. Pragmatism is described as a way of using multiple paradigms in the same study, which will lead to a more evolved answer of the research question (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Given the paradigms existing in research philosophy, interpretivism will be used to conduct the research by integrating the individual perceptions and their expectations through social constructions (Dudovskiy, 2016). Since the understanding of learning processes within a nonprofit organization is the objective, the interpretivist approach will provide the opportunity to identify findings that are accurate and reliable. Moreover,

17

when analyzing the learning processes in crises, elements connected to social constructions will not be avoidable since the way a person acts in the brink of a crisis differs depending on the individual, which yet again points toward interpretivism (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Interviews will be conducted and used as primary data. Furthermore, from the primary data, it will be possible to bypass the deficiency that can be created by exclusively looking at secondary data and not taking social perspectives and organizational differences into consideration. Also, the secondary data will be collected by using a variety of sample keywords and articles.

4.3. Research Approach

Three main approaches that could be used when conducting the research are induction, deduction, and abduction (Saunders et al., 2016). Firstly, the inductive approach is based on understanding the data collected and the knowledge related to the observation made (Thomas, 2003). Furthermore, the approach is used to collect data which will lead to untested conclusions being presented (Given, 2008). A deductive approach is developed from a theory or a conceptual framework and is commonly used as a research strategy when developing a hypothesis to test the theory. By forming a hypothesis and examining the premises as well as testing them, the findings could be analyzed. If the result does not match the hypothesis, then it is false, and the hypothesis should be rejected (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2013). Abduction, however, is the operation of stating a hypothesis connecting it to known patterns. It is based on anomaly or surprising information that occurs in the research and makes it possible to develop a new hypothesis (Dew, 2007). The approach uses a combination of deduction and induction since the strategy moves both from theory to data and from data to theory (Saunders et al., 2016).

This thesis focus on developing the already existing theories within the field of study which is inductive reasoning. The aim is to understand to what extent learning processes are implemented, and this will be done by conducting interviews where open-ended questions are asked. The data will be collected and used to further analyze the research area, and by connecting it to existing theory the intention is that it will allow for valuable findings to emerge. Throughout the thesis, the inductive approach is used, however, with

18

minor exceptions since the study does not aim to develop new theory, hence, an existing theory is present when analyzing the data. The exceptions mainly appear in the interview questions, since some of the questions were developed towards the background of the existing theories. Despite the presence of these abductive elements in a minor part of the thesis, the research approach is overall inductive.

4.4. Method

4.4.1. Literature Search

With the frame of reference in mind, all the data has been collected from electronic- and physical sources. The electronic data consists of a mix of scientific articles and electronic books, where the majority has been obtained from Google Scholar, however, in the frame of reference section, only academic journals have been analyzed and used. The main reason Google Scholar was used is because of the wide range of academic journals and data it obtains. Despite that, one problem that appeared was that we did not have access to some articles on some databases. This was solved by using other databases that our University had access to, it often was a database where the scientific article originated from. This was, for example, SAGE journals online, Scopus, and Taylor & Francis Online. Aside from these databases, the majority of the articles were still collected from Google Scholar, since it displays the most relevant articles within the research field, and this, for instance, can be controlled by looking at how many have quoted the article. In regard to the physical sources, the books were all accessed through the library at Jönköping University. The data collection process is found and summarized in Table 2.

19

Table 2- Visual Overview of the Data Collection Process

Frame of References

Databases Google Scholar, SAGE journals online, Scopus, Taylor & Francis Online, Academia

Main Theoretical Fields Crisis Management, Nonprofit Organizations, Learning Processes

Search Words Crisis Management; Execution Plan; Crisis Management Execution Plan; The View of Crisis Management Execution Plan; Perception of Crisis Management; Crisis

Nonprofit; NPO; Not-for-profit; NPO Health Organizations; Nonprofit Sector Crisis; Handling Crisis NPO; Healthcare; Humanitarian Organization

Type of Literature Scientific articles, Books, E-Books

Criteria to Include an Article The search word had to match either the title of the article, be in the abstract, be one of the keywords or be included in the content when searching in the text.

Year Span of the Articles 1976 to 2019

Source: Developed by the Authors.

4.4.2. Sampling

Taking into account that this study uses the research philosophy interpretivism, the most relevant method of collecting data was qualitative. The most suitable alternative then was using interviews to get the primary data. Given that it would be impossible to reach to all nonprofit organizations in Sweden, a sample representing the field was used. Considering that the main objectives of this thesis are to explore how nonprofit organizations manage internal crisis and what can be learnt from that, a non-probability approach was most relevant when selecting the sample. In other words, the sample was not randomly chosen (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The organizations were included in the research based on some

20

requirements that they had to fulfill. The first requirement was that they all had to be within the humanitarian or money collecting sector. In addition to that, the organization needed to be a “90-konto”, which translates to “the 90 account”. The be qualified to be a “90 konto”, an organization is only permitted a maximum of 25 percent of total revenue invested in administration and the remaining 75 percent of total revenue should go to the end cause (Insamlingskontroll, 2020). The interviews were conducted in Swedish since that is the native language of the respondents. The data has been translated into English afterwards, and effort has been put in translating the quotes as accurately as possible so that the translated statement would uphold the same meaning as in its original version. The Swedish quotes can be found in Appendix 2. This thesis has one main type of respondent which is the participants from the organizations. The rationale behind interviewing several different organizations is to examine their opinions and viewpoint of internal crisis management. Furthermore, to investigate if there is any type of similarities in previous research but also to see if there are any links to the expert’s point of view.

The sampling method used for this thesis is called judgmental or purposive sampling, this means that the participants were selected for a number of reasons. The judgmental method works in the sense that the participants are contacted because of either their expertise and/or earlier experience within the specific topic. In other words, the participants have knowledge in the field and therefore are in a position to share relevant insights and opinions. If the person contacted were not suitable as a participant, they forwarded the email to the correct person within the organization, which is an example of how snowballing or network sampling works (Collis & Hussey, 2014). For this thesis, the most suitable person to answer in the interviews would be managers in the crisis management department. Preferably the Head of Crisis Management/Communication, due to the fact that they are responsible for everything happening both internal and external and therefore having most insights into how the organization is dealing with this matter. Due to the fact that not all organizations have a crisis management department, other employees responsible for this type of task were selected. The participants in the interviews have positions as Secretary-General (Bo Wallenberg), Head of International Department (Anders Mårtensson), Head of Crisis Management and Emergency Preparation (Lasse Lähnn), and Press, Public Affairs (Liv Landell Major). Other positions participant has are

21

Responsible for Internal Communication & Employer Branding (Beata Fejer) or Operations Manager (Maria Berg). With this, a variety is seen of people having different positions at the organizations.

Due to that the interviews are being conducted in a time of crisis in forms of the Covid-19 virus, all interviews were done by telephone to eliminate any unnecessary risk. 37 organizations were contacted, and out of these, five organizations had the ability to participate in the study. Out of these five, three are some of the biggest NPOs in Sweden, and one is one of the biggest internationally, for this reason, it is possible to be confident with the subset. There are over 430 active organizations in the “90 konto” (Dagens Industri, 2017), hence the 37 organizations that were contacted and offered to participate were carefully chosen and not randomly picked. A full list that contains more details of the interviews can be found in Table 3.

22

Table 3- Interviews

Name Organization & Mission Statement

Position Date of the Interview Interview Length Technique Bo Wallenberg Anders Mårtensson Barnmissionen: We are working for a world where everyone can live a worthy life (Wallenberg, 2020). Secretary-General Head of International Department 2020-03-02 00:41:32 Telephone

Lasse Lähnn Röda Korset: When a crisis and disaster occurs, we act quickly on the site. The Red Cross fight to make sure that no one is left alone in a crisis (Röda Korset, 2020).

Head of Crisis Management and Emergency Preparation

2020-03-03 00:43:23 Telephone

Beata Fejer Cancerfonden: The goal is for fewer people in Sweden to suffer from cancer and more to survive the disease (Cancerfonden, 2020).

Responsible for Internal Communication & Employer Branding 2020-03-06 00:27:48 Telephone Liv Landell Major Majblomman: We work to combat child poverty in Sweden. This is done by distributing financial aid, influence decisions, and fund research, which will give children in Sweden what they are entitled to (Majblomman, 2020).

Press, Public Affairs

2020-03-17 00:40:01 Telephone

Maria Berg Barnen Framför Allt - Adoptioner: We work in the best interests of the children through adoption, sponsorship, and assistance (BFA, 2020).

Operations Manager

2020-04-07 00:15:55 Telephone

23

4.4.3. Interviews

There are several approaches on how to collect qualitative data, and focus groups, protocol, observation, interviews, and diaries are just a few examples of them. In regard to this type of thesis and research, interviews or focus groups are considered to be the most suitable option. It is decided to only conduct interviews since gathering respondents for the focus group would be problematic due to some of the organizations do not have the time, money, or enough employees to participate in this type of occasion. Furthermore, conducting focus groups would be problematic due to the difficulty of finding a suitable time and place where all are able to attend since the organizations are located in different parts of the country. In terms of using interviews when collecting data, the participants that take part will be asked questions related to the topic with the intention to collect information on what they feel, think or do in specific situations. Since the purpose of the thesis is to gather insights of how nonprofit organizations work with crisis management and what learning process that can be implemented to this, open-ended questions will be used rather than closed questions. Meaning the questions asked will not be able to be answered with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’, instead, each question will be discussed and result in deeper insights (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Interviews can either be semi-structured or unstructured. When using unstructured interviews, the interviewer does not prepare questions in advance instead they are developed while conducting the interview. In contrast, in semi-structured interviews, the questions are prepared by the interviewer beforehand, however, some new questions may arise during the interview, such as follow-up questions for example (Collis & Hussey, 2014). For this research study, open-ended questions were developed in advance and asked during semi-structured interviews. The questions were divided into firstly background questions about previous experience and about the organization in general. The following questions were about general perception concerning crisis and different responsibilities within the organizations. An example of such a question is “What is your view on crisis management in the company? How do you work with it?” Lastly, the questions focused on learning processes in more specific terms, one question asked was “What routines do the organization have after the crisis? How do you follow-up after a crisis?”. The questions were developed by the authors to enable a discussion that could lead to valuable insights and findings within the research area. Not all questions resulted

24

in usable findings per se, however, they helped create a comprehensive view and a rewarding discussion of the opinions and experience in the subject. If requested, the questions were shared with the interviewee beforehand.

The interviews lasted between 16 and 43 minutes and are from which the empirical data was collected. The quotes used in this section is translated from Swedish, the original Swedish quotes can be found in the Appendices 2, and if requested, the recordings can be provided. The questionnaires are attached both in Swedish, since that is the language that interviews were held in, and in English, and these can be found in Appendices 1a and 1b. In order to have successful interviews, there are a few factors one has to take into account. The first point is the researcher’s knowledge about the topic and the organization’s interviewing. Hence, to be able to conduct a high standard interview, the researcher needs to have general knowledge about the subject. Secondly is credibility, when using the semi-structured method, the questions were prepared before the interview to place. This is so that the interviewees that wanted to prepare beforehand could, for example, if they wanted to discuss any question with a colleague. Thirdly is the chosen location, this is in regard to both the interviewer and the interviewee. Most important is that the interviewee felt comfortable with the location since the whole research is dependent on their participation. All the interviewees that participated in the research chose the location themselves since the interviews were done by telephone. This is why the fourth and last issue is regarding the appearance of the researcher, which is connected to the dress code, behavioral standard, and time management, however, this was not extensively relevant for this study since the interviews were conducted by telephone (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2016).

Techniques that can be used when conducting interviews include face-to-face, telephone, or online (Saunders et al., 2016). Face-to-face and telephone were considered to be the most suitable methods for this type of research. However, as mentioned previously about the Covid-19 virus, all the interviews were conducted through telephone. The advantages when using telephone interviews is that there is no travel cost in regard to geographical distance, but at the same time the personal contact remains. On the other hand, there can be some limitations when using this technique as well. Many times, when conducting a telephone interview, it is during working hours which then can restrict the participant find

25

time for the interview. Another problem can be that the respondents might not be as open to answering questions when talking on the phone which then will affect the quality of the answer. The recording was made of the interviews as validation for trustworthiness, but also to use for transcription later on (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The interviewees approved to be recorded before the interview was started and the recording was made through a mobile telephone since a high quality of sound was as desired. Notes were taken during the interview to complement the recording. After each interview was held, a transcription of it was made so that the data could be used in analyzation section.

4.4.4. Analysis of qualitative data

When conducting semi-structured interviews, as stated by Saunders et al. (2016), a variation of questions will be asked, and all might not be relevant for the end discussion. They are still included and important for the flow of the interview, and additional questions might be added during the interview in order to explore the research question further.

Thematic analysis is a tool used when conducting qualitative research. The method identifies existing patterns within the data collected and it provides a theoretical framework used to identify the themes that exist within the data. Moreover, the analysis makes it possible to avoid producing a complete grounded theory analysis within qualitative research. By using thematic analysis as a tool, it attempts to capture the experiences and the reality of the participants, which in this case is from the interviews. In addition, the analysis can also be used to further explain the existing discourses and the effects of it. In order to form a thematic analysis, the data will be coded to identify the common themes within the data. Firstly, the data shall be collected and transcribed, this will be done to interpret the data as well as an opportunity to become more familiar with the data. The transcription will be done in an ethical and precise way, without any changes to the nature of the quotes. Furthermore, the data analysis will be done through coding, which is an essential process of identifying important aspects of the data collected (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Furthermore, after analyzing the data, allocating codes, and analyzing the similarities that have been presented in the coding, common themes in the data will be shaped.

26

From the interviews, it was possible to find fourteen suitable codes and five common themes, shown in Figure 3, that aligned with the previous research, and since the answers from the interviews did not differ notably, the trustworthiness of the research result is argued to be high. Hence, similar answers indicate that a level of saturation has been reached, which is essential in trustworthy results and conclusions (Tay, 2014). For this reason, it is possible to argue that additional interviews are not necessary since it would not add value to the study, hence, the answers provided by the empirical data are regarded as trustworthy.

Figure 3- Codes & Themes

27

4.5. Trustworthiness

As mentioned by Saunders et. al. (2016) there are four main aspects that need to be considered when conducting research, and these are reliability, validity, interviewer, and interviewee bias. However, since this study will be conducted through qualitative and semi-structured interviews, the reliability is not considered relevant, since the aim is to gather thoughts and opinions, not necessarily stated facts. The organizations included operate during different circumstances, hence, they might have diverse opinions about what is most essential in the questions.

The interviewer and interviewee bias are where the interviewee might induce a false response due to the fear of being overheard, or the interviewer might allow one’s own subjective view to influence accurate recording and interpreting of participants’ responses (Saunders et al., 2016). However, this risk was reduced through various measures taken both before, during, and after the interviews. Firstly, the interview was asked to be held in a separate, quiet location where there was nothing to disturb the interviewee. Secondly, the respondent was always put in focus, and all questions were open-ended and developed to guide the interviewee giving the necessary information. The interviewee bias was further decreased by formulating the questions in a way where they were not asked to talk about their company in specific but rather the experience of crisis management within the company (see Appendix 1a). Asking the participants to talk freely about their experience on the subject helped limit both interviewer and interviewee bias. Furthermore, emphasis was put on creating an environment where the participant felt comfortable by asking about their experience and opinions, hence, further decreasing the interviewee bias.

Another key aspect that is connected to the level of trustworthiness of the research is dependent on the credibility. When the researchers evaluate and describe their experience as researchers, the credibility increases, and to be able to do this, self-awareness is required (Koch, 2006). The researchers’ self-awareness is therefore revealed in three aspects. Firstly, when initiating the research process, emphasis was, to a great extent, put on learning about research methods. It was also highly prioritized to gain as much knowledge about the different theories, the business area, and crisis in detail prior to initiating the data collection process (Cope, 2014). What also adds to this aspect of

28

credibility is that one of the researchers has studied a course in Crisis Management and gained valuable knowledge and experience within the subject. Secondly, throughout the interviews, particular attention was put on creating an environment in which the participants felt comfortable and trusting towards the researchers. This was done by acting professionally and being careful to provide all the necessary information prior to the interviews. By doing this, the credibility of the data collected increases. Lastly, tutoring seminars, workshops, and lectures were attended during the course of the research process, were guidance and peer-evaluation contributed to the development of the study (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

4.5.1. Ethics

When conducting interviews, it is of great importance to conduct the research and interviews in a manner that does not cause any harm nor distress, hence, the choice of interview methods and questions is important (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2016). For this reason, all the participants were asked to permit that the interview was recorded, and they were also given the option of being anonymous. Additionally, the participants were informed that they will be quoted and that they will be asked for approval before publication. The intention of asking for consent was to protect all parties involved. Before the start of every interview, the purpose of the data collection was explained as well as what the information will be used for. This is particularly important since collecting information and using it for other reasons would be considered unethical behavior. No data will be altered to fit an ulterior motive, by doing so, the information collected will be able to be analyzed in an ethical way which will lead to the research questions being investigated in an adequate way. Furthermore, the interviews held were established without any external benefits that could affect the participant’s answers.

29

5. Empirical Data

This chapter includes findings that are relevant to the empirical data collection. Presented in this section is the empirical data that has been collected from interviews held by the researcher, this will be displayed in quotes from the interviewees and connected with arguments and theories within the study. The data is divided into two sections, one with the organization's view on crisis management and the second on learning processes.

5.1. Interviews

The findings of the qualitative data consist of the five interviews from the nonprofit organizations. Important to highlight is that the template for the questions was adapted depending on how the interviewee answered the question, this is to obtain as much information as possible. While interviewing the organizations, some viewpoint was shared, but there were also questions in which the answer and general opinion differed depending on which role and experience the participant had, and also depending on the size of the organization. In order to perform a thematic analysis, this section is divided according to the five themes shown in Figure 3.

5.2. Crisis Planning

One fact that all organizations had in common was that they have a crisis management plan to some extent, Anders Mårtensson states

“Yes, we have a plan for how to act. Within the organization we have who should contact who. It is not like we have a habit of it, we are as surprised everytime it happens.”

Anders Mårtensson (Barnmissionen) 6:36

The same goes for BFA, who is a smaller organization with only 7 employees. Maria Berg answers the following on their viewpoint of having an action plan.

“We have an emergency plan, absolutely, that was developed with the board. I feel that in this small type of organization that we are, where we have very high demands on what

30

we need to deliver and so on, internal crisis management falls very low on the priority list.”

Maria Berg (BFA) 3:02

Additionally, Beata Fejer explain the action plan of Cancerfonden

“The focus is mainly to foresee the crisis and work predictively by actively counteract crisis by maintaining high quality in the everyday operation and make sure that small mistakes do not grow into confidence crisis or reputations that creates unnecessary harm or confusion. We know that the public confidence for Cancerfonden is crucial for us to achieve our vision: to beat cancer.”

Beata Fejer (Cancerfonden) 5:47

5.3. Managing Crisis

In regards to managing a crisis, Lasse Lähnn states that Röda Korset have one person that has the main responsibility, he also adds that

“We have a viewing function since many years back, however, we have increased their responsibility allot to the extent that there is one employee in the preparedness who works around the clock nationally. And this person has the responsibility to analyze the world and control all the time what's going on in the society, both within the organization and in the society.”

Lasse Lähnn (Röda Korset) 9:34

However, Röda Korset has had a major crisis in the past, caused by the management, Lasse Lähnn previously mentioned in the interview that

“There is an event that affects us a lot, that still to some extent affects us and that was in relation to Johan af Donner.”

31

The quote refers to the crisis where the fundraiser manager embezzled millions from Röda Korset, a crisis that highly impacted them in the past since it resulted in a major confidence crisis affecting them both fiduciarily and economically. Even though it happened over 10 years ago, they have not yet fully recovered and the organization still needs to work with this regularly when the question is brought up. They always have in mind the risk of experiencing another crisis, since they are convinced that a second crisis would highly damage the organization further, even more than the first time.

All organizations agree that the crisis plan is a living document that is constantly changing, Liv Landell Major shares that

“There are always things that can get better, I personally am particularly interested in how different actors act in the media.”

Liv Landell Major (Majblomman) 19:10

Furthermore, Lasse Lähnn shares that in regards to learning from past crises they have implemented an evaluation and learning system that they have developed in order to evaluate different crises depending on the type and thereof magnitude of the event. Additionally, he explains

“...there are routines for how we, through different workshops and questionnaires conclude the learning, and then also a learning-plan for how much time each thing should take once it is implemented.”

Lasse Lähnn (Röda Korset) 20:39

Cancerfonden have a similar process where they learn by

“By making a thorough and profound evaluation and being concrete in what we need to change.”

Beata Fejer (Cancerfonden) 10:13

32

“Well, at those events where we have had a bigger crisis we have done a, well what to call it, a summary and a follow-up to identify what we did and how it turned out, and what learning can come from it.”

Maria Berg (BFA) 7:37

Liv Landell Major agrees with the importance of evaluating the event by stating that

“I think it is the most obvious thing within crisis management, going back and see, briefing each other.”

Liv Landell Major (Majblomman) 30:17

There is also a learning possibility in observing other organizations, Bo Wallenberg explains that

“We are 34 organizations that meet kind of regularly. Then you have special meetings for the management within the organization, and you have special training for the staff that works in the field and so on. And here we are very open with each other and I have attended many meetings where an organization gets to tell what happened when they experience a major crisis.”

Bo Wallenberg (Barnmissionen) 14:02

BFA has a regulatory that they work against together with other adoption agencies. Which is also where they mainly get their knowledge and directives form, this is similar to how Barnmissionen works

“There is another organization that we have been a part of, FRI, Frivilliga Organizationers Intresse (voluntary organizations interest). They are the ones organizing the 90 accounts. They have had many of these. As soon as there is a crisis within an organization, they want the organizations to share their experience as soon as it has passed. ‘That this is what we did and this happened’.”