Communication for Development One-‐year master

15 Credits Spring/2016

Kenyan Capitalist Narrative

A discourse analysis of online media reporting on the

Global Entrepreneurship Summit 2015 in Nairobi

Abstract

A capitalist world system is dictating how the global economy is organised, and entrepreneurship is suggested as a global solution for economic development. In development practices bottom up approaches such as social entrepreneurship are challenging the traditional donor-based model. The Global Entrepreneurship Sum-mit (GES) is a United States lead initiative to promote entrepreneurship and eco-nomic ties with the Western world. This study analyses the online media discussion around the GES 2015 held in Nairobi, with focus on answering how sampled Ken-yan blog and online news articles construct and contribute to KenKen-yan entrepre-neurship discourse with their reporting around the GES, whether they reflect a more global or local capitalist narrative, and finally what kind of development think-ing the entrepreneurship discourse reflects. A literature review builds context by describing the development of the Kenyan capitalist narrative. The empirical part applies a mixed method approach, with elements from content as well as discourse analysis in studying a sample of 120 Kenyan blog and online news articles. The analysis reveals that the local online reporting around the GES reflects a global capitalist narrative with a highly optimistic attitude towards entrepreneurship as a means to create economic growth as well as social change.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

2. Research questions ... 3

3. Literature review: Capitalism in Kenya ... 4

3.1 Periods of capitalism in Kenya ... 4

3.1.1 Colonial Period ... 5

3.1.2 Neo-‐colonial period ... 7

3.1.3 Post-‐colonial period ... 9

3.1.4 Informationalism & entrepreneurialism ... 13

3.2 Kenya in the 2000s and beyond ... 16

3.2.1 Becoming an East African ICT hub ... 17

3.2.2 Focus on growing entrepreneurs ... 17

3.2.3 Mobile innovation pioneers ... 18

3.2.4 Challenges ... 19

3.3 Capitalism’s effects in Kenya ... 21

3.3.1 Changes in moral economy ... 21

3.3.2 Increasing informal sector ... 22

3.3.3 Environmental concerns ... 23

3.3.4 Capitalism and ethnicity ... 24

3.4 Entrepreneurialism and social entrepreneurship as the new development paradigms 27 3.4.1 Kenyan examples ... 29

3.4.2 Who is a social entrepreneur? ... 30

3.4.3 Problems with social entrepreneurship ... 32

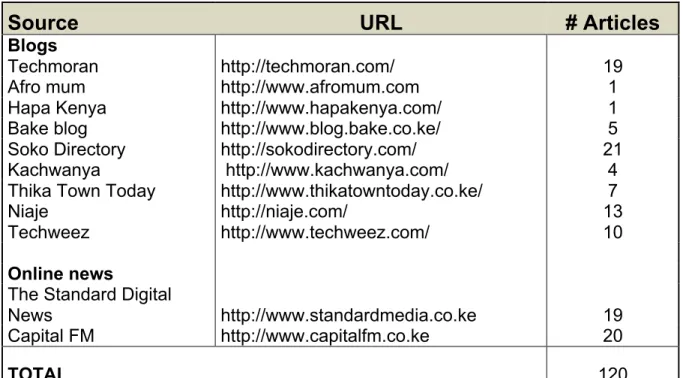

4. Analysis: Kenyan online media reporting on GES ... 33

4.1 Methodology ... 35

4.1.1 Sample selection ... 35

4.1.2 A word-‐frequency analysis ... 39

4.1.3 Software aided analysis and grouping of texts ... 41

4.1.4 Interpretation of obtained discourse themes ... 42

4.2 The sample speaks ... 43

4.2.1 Key themes ... 45

4.2.2 What remains uncovered ... 52

5. Conclusions ... 54 List of References

1. Introduction

Economic development and the private sector are gaining more and more attention within global development discussions. Especially China’s economic growth and increased investment in African countries has put economic activity in the focus of development initiatives. Many actors, from organisations and governments to the advisory high-level panel of the UN Secretary-General, emphasise the importance of economic growth, trade and job creation in poverty reduction actions (Lucci 2012).

In the prevalent global capitalism, governments see it as their duty to create suita-ble conditions for economic prosperity for the country they represent. Large com-panies, previously trusted as stable employers, are constantly cost-optimizing their operations, which results in mass-scale layoffs and worsening global unemploy-ment. Since less and less people will be able to enjoy secure employment, entre-preneurship is seen as an important agenda for battling economic decline and un-employment in the North and South alike. It is therefore very interesting to examine the forms of entrepreneurial activities as a complementing element of more tradi-tional internatradi-tional development. Can entrepreneurship be harnessed to tackle un-employment and poverty?

President Obama has elevated entrepreneurship to the forefront of the United States’ engagement agenda underlining it globally as a means to “expand econom-ic opportunity for all, especially women and youth.” (FACT SHEET: Global Entre-preneurship Summit 2014). One of the instruments for such engagement, The Global Entrepreneurship Summit (GES), was launched in Washington D.C. in 2010. The GES has since expanded, and been hosted by several countries sharing this mission. The 6th Global Entrepreneurship Summit (GES) was organised in Kenya in July 2015 with President Obama as co-host.

Throughout the past decade Kenya and other East-African countries have wit-nessed faster economic growth than ever before in the countries’ history. Kenya,

with an annual economic growth of around 5% (Malingha 2015) is one of the rising economies in Africa. A growing middle class is creating demand for more and more services and people’s rising education level is attracting more foreign investors. There has been a push to create more opportunity, particularly within Information and Communication Technologies, and Nairobi alone hosts several high tech busi-ness incubators, having earned the nickname Silicon Savannah.

Despite of the economic growth, as well as evangelising on entrepreneurship as the way forward, prosperity is not being equally distributed and millions of people continue living in poverty. Large numbers of African people still leave their coun-tries as economic migrants with the hopes of starting a better life overseas. Unem-ployment in Kenya alone is fluctuating around 40%.

Entrepreneurship is nothing new in a country where almost 80% of the work force is trying to make a living in the informal sector, and thus are not part of the formal capitalist system. New, more socially and culturally inclusive models of economic activity, such as social entrepreneurship, have emerged to bridge the gap. Interna-tional development actors are experimenting with profit-making business-like mod-els to complement (or even replace) more traditional NGO lead development initia-tives. Social enterprises are often locally bread, and thus challenging large donor lead projects as more local needs oriented and agile.

Communication for Development (C4D) scholars such as McAnany (2012 a) and Servaes (1999) have emphasised the role of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in facilitating social change. The development and spread of these technologies have not only enabled business opportunities around ICTs but also increased connectivity and emergence of a wider, more participatory, variety and reach of media such as blogs and social media platforms. Communication, in both technology and content, thus holds a key role in enabling change.

This thesis project looks at Kenyan reflections on capitalism, entrepreneurship and development by analysing blog and online news articles around the Global

Entre-preneurship Summit of 2015, a large-scale event that promotes the prevailing eco-nomic and development paradigms.

In the first part a literature review outlines Kenyan appropriation of capitalism, velopment and entrepreneurship by describing how these have emerged and de-veloped from the colonial past till today, and what are their implications. The last chapter discusses entrepreneurship, with a particular focus on social entrepreneur-ship, as the emerging paradigm within international development practice.

The second part of the thesis examines the type of sentiments, thoughts and ideas provoked by The GES and the way this discourse enforces or contrast the findings of the literature review. The sample of analysis consists of blog and online news content published before, during and after the summit that took place on July 24th and 25th, 2015.

2. Research questions

This study analyses the discussion around the Global Entrepreneurship Summit 2015 facilitated by digital media channels, including blog and online news articles.

The research is focused around answering the following questions:

How do Kenyan blogs and online news construct and contribute to Kenyan entre-preneurship discourse with their reporting around the Global Entreentre-preneurship Summit 2015?

Do the texts reflect a more global or local capitalist narrative? And what kind of sentiments, thoughts and ideas arise?

As mentioned, entrepreneurship and for profit activities have increasingly been linked with development. Thus it is of interest to also pose the question:

3. Literature review: Capitalism in Kenya

A capitalist world economy, a term coined by Immanuel Wallerstein (in Hoogvelt 2001), refers to the current dominant world system of how social and economic life is organized in the majority of the world. The term ‘capitalism’ is used throughout this thesis as referring to this predominant system. Interestingly capitalism has been able to shift and transform during the course of history, being demonstrated and enhanced via various political structures: from its early emergence as Europe-an mercEurope-antilism Europe-and colonialism, through post war US hegemony Europe-and the cold war and to today’s globalized information age, reaching all continents.

In the following Literature Review I outline the progress of the capitalist narrative and its effects in Kenya: how the nation has developed through colonial times and early days of independence to its current position as one of the fastest growing economies in the African continent, and how this is reflected from a social and cul-tural point of view. In parallel I reflect on the history of development approaches with focus on communications.

3.1 Periods of capitalism in Kenya

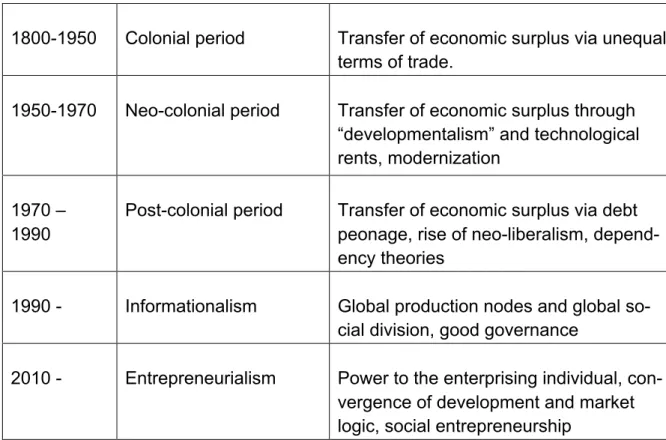

For the framework of analysis I use an adaptation of Hoogvelt’s (2001) division of the development of capitalism presented in the below table 1. I complement Hoog-velt’s division with Castells’ concept of Informationalism as the fourth stage, and conclude the chronology with the current trend of promoting entrepreneurship as the means of (economic) development, named here as ‘entrepreneurialism’.

The foundation for Kenyan capitalism is laid in the colonial period. Followed by neo-colonial and post-colonial periods, when Kenya enters the global economic space as an independent nation, and becomes the target of development action from the West. In the 1990s and 2000s innovations within communication break more barriers of economic development, and promoting entrepreneurship becomes

one of the main storylines in the current capitalist narrative. The below chapters elaborate on this chronology.

1800-1950 Colonial period Transfer of economic surplus via unequal terms of trade.

1950-1970 Neo-colonial period Transfer of economic surplus through “developmentalism” and technological rents, modernization

1970 – 1990

Post-colonial period Transfer of economic surplus via debt peonage, rise of neo-liberalism, depend-ency theories

1990 - Informationalism Global production nodes and global so-cial division, good governance

2010 - Entrepreneurialism Power to the enterprising individual, con-vergence of development and market logic, social entrepreneurship

Table 1. Periods of capitalist development in Kenya 3.1.1 Colonial Period

The Industrial Revolution and subsequent increase in population lead the world powers to seek new ways to expand, thus began the colonial period and European nations’ race to conquer more territories. Colonial ties and favourable production relations helped Western Europe accumulate wealth and establish a strong posi-tion as the “power region” in the world. In order to keep the colonies up to a certain level to serve the motherland, the colonizers took up many efforts to develop and modernize the colonies. They built infrastructure and established educational

insti-tutions to better equip the local societies for serving the needs of the economy. Commercialism and civilization went hand in hand. (Hoogvelt 2001)

Kenya first became a protectorate under Britain in 1895 and later a crown colony in 1920. The time under a colonial rule was about keeping a fine balance between European settlers, foreign capital and indigenous class forces (Swainson 1977).

A small European settler class had established estates to produce various agricul-tural products on the fertile lands. With direct ties to the colonizer, and more accu-mulated capital on their side, they were politically powerful and held out of propor-tion influence in the local administrapropor-tion. The settlers expected support from the local administration in fulfilling their interest, including favourable taxation, regula-tion and supply of labour (Swainson 1977).

One example of such arbitrary governance is the Coffee Plantation Registration Ordinance from 1918 that forbade Africans from growing coffee and thus pushing them to be available for wage labour in the European estates. In another ruling from 1935, Marketing of Native Produce Ordinance restricted wholesale marketing only to Europeans (Ake 1996). Such charters made it difficult for Africans to devel-op any other skills than manual labour thus making sure that the economy was to develop in the hands of white capitalists.

In 1923 however, the colonial administration declared that native people’s interests were to be paramount in British territories. This lead to political disagreements and power battles between the metropolitan admin in Britain and local settler admin over the rights of African and Asian Kenyans to political representation in the colo-ny. In the end the settlers managed to assert their power, finally forming a Europe-an minority stronghold in the late 30s. (Swainson 1977)

Brett (In Swainson 1977) portrayed the settlers as first 'economic nationalists’ meaning that they had the power over capital and were promoting domestic accu-mulation. Due to the more protective policy and more internally allocated

invest-ments, Kenyan production capabilities exceeded those of other East African colo-nies. Subsequently however this higher concentration of internal accumulation helped to establish production base as investment was allocated in the means of production. After WW II there was enough capital to facilitate the emergence of industrial manufacturing.

3.1.2 Neo-colonial period

Coming to the tumultuous first half of the 20th century, colonialism as the hegemon-ic organization of international production relations had come to a halt. According to Hoogvelt (2001) the very success of such global wealth accumulation had creat-ed contradictions and a necreat-ed to change, in order to successfully move forward. As capitalist markets and market institutions had been set up, including foreign planta-tion ownership, long-term concessions for mineral exploraplanta-tion and full ownership of multinational companies’ subsidiaries, there was less resistance for political inde-pendence in the colonies. The colonial period thus set a structure for international capitalism to continue ruling in the following, neo-colonial era.

The late 1940s and early 1950s introduced “developmentalism”, a top down planned development approach with roots in the rebuilding efforts of war torn Eu-rope. Referred to as the period of modernization in development theory, the time emphasised the importance of investment and technical change to increase local industrialisation (Hoogvelt 2001). Development became somewhat of a political weapon in the midst of the cold war, as capitalist West competed with the socialist East to keep the Third World countries in their respective spheres of influence and trade (Moyo 2009).

Communication for Development (C4D) as a concept emerged around the same time with focus on the widening reach of mass media (Servaes 1999).

Early C4D Scholars such as David Lerner observed that mass media was increas-ingly introducing the modern world of the West to the traditional peoples (McAnany

2012 a) However, as the more top-down, one-size-fits-all modernization approach to development, also communication at the time was a more one-way, sender-to-receiver process (Servaes 1999), Several communications professionals, such as Childers (in McAnany 2012 a), who were involved in the development initiatives were pointing out that the lack of communication with the local people was often a reason behind failure of projects.

New organisations and aid programmes driving modernization included US initiat-ed International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. According to Nulty (2009) the latter organisation first focused on sustainable and equitable develop-ment, and encouraged Third World countries to develop their own industries but soon changed this policy and pushed for countries to welcome and provide incen-tives to foreign firms.

The third world countries made several pleas for better access to markets, reforms in international monetary systems, changes in aid flows and establishing orders of conduct for multinational corporations. However, the international bodies did not show much response to these requests. (Hoogvelt 2001) According to McAnany (2012 a) this more proactive approach to endogenous and self-reliant development was to contribute to a future C4D turn toward the discourse around participation and empowerment in the coming decades.

According to Ake (1996) many African leaders also saw the ideology of develop-ment as a way to strengthen their own internal stance, to use it as a “strategy of power that merely capitalized on the objective need for development”. An ethos of hard work was established as East African leaders changed the nationalist slogan from Uhuru (freedom) to Uhuru na kaze (loosely: “freedom means hard work”). Achieving development would require utmost obedience and conformity. By using the ideology and discourse of development local leaders found a way to justify sin-gle party systems and criminalization of political oppositions thus strengthening their political hegemony.

Kenya was reflecting the global transformation with a reorganisation of the econo-my. International financial capital was gaining more ownership and control and large multinational companies were entering the market. Creating an industry of indigenous cash-crop agriculture for the world market became the priority of the Kenyan state. The settler’s monopoly of production and distribution in Kenya was to come to an end. The procedure was outlined in the Swynnerton plan of 1954. Increased aid from the metropolitan admin was targeted to create the surrounding enabling structure such as healthcare and education. (Swainson 1977)

This transformation was reflected also on a political level. The settler minority had to give up power for the rising local middle class, supported by the metropolitan administration. However, Europeans dominated the political entities. This created juxtaposition between the interests of European businessmen, larger farms running on international capital and smaller scale settlers who had benefitted from more nationalistic policies. At the same time there was more pressure from the Africans to dismantle the unfair policies including land ownership. The situation culminated in an armed conflict between the British armed forces and local rebellions of the Kikuyu tribe known as the Mau Mau movement. The conflict underlined the urgen-cy of an African political representation.

Under the leadership of the main party KAU (Kenya African Union) and its leader Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya finally became independent in 1963 with an indigenous bourgeoisie replacing the European settler class. (Swainson 1977)

3.1.3 Post-colonial period

The colonial times had left behind poor organisation of the state and a wide gap between the local bourgeoisie elite and a poor majority population in most third world countries. According to Hamza Alavi (in Swainson 1977) many newly inde-pendent countries inherited a state apparatus that was not developed by native bourgeoise but by foreign imperialists and was thus capable of subordinating

do-mestic classes and emphasizing foreign interests. Swainson (1977) with many so-cialist academicians of the time states that East-Africa was forced to integrate to foreign capitalism. Whereas according to Ake (1996) prominent African leaders, including Kenyatta, believed that overcoming the humiliation of colonization re-quired the nations to become more competitive and to overcome economic and technological barriers actively seeking to “catch up with the West”.

To keep internal unrest at a low, the local elite would stir up nationalistic feelings in the newly established independent nations by blaming foreign companies of con-tinued imperialism. Towards the 1970s many third world countries had established nationalization policies, which meant that foreign owned companies were sold to local bourgeoisies or taken over by the state. (Hoogvelt 2001)

However, the countries needed capital to maintain production, and in the absence of efficient local financing instruments, they had to seek funding from international banks. This lead to the rise of debt as a form of extracting and transferring eco-nomic surplus from South to North. Global deregulation actions started in the 1980s formed a variety of financial institutions and funding instruments, which helped formulate and strengthen the power of financial capital markets. Coming to the 1990s, lending and debt had become an industry of its own. By the end of the 1980s the cumulative third world debt was 1 trillion USD, a third of combined de-veloped world GDP (Hoogvelt 2001), and it had cancelled out many economic gains realized from development efforts in the 1960s and 1970s. This meant that the countries’ focus shifted to managing debt payment schedules over promoting development projects (McAnany 2012 a).

The fact that many Third World countries were not modernizing and developing at a desired pace sparked criticism towards the development efforts. Dependency theory, a popular development paradigm originating from Latin America spread also among underdevelopment critics in East Africa.

system, stating that directing foreign investment inflows to export industries was contributing to the surplus extraction in favour of the core. Thus denying the pe-riphery the opportunity for internal accumulation and forming a greater dependency of the periphery from the economic core countries. (Swainson 1977)

Postcolonial theorists, such as Fanon (In Swainson 1977) also criticised the local African middle class of acting in favour of neo-colonialism and thus hindering the nation from advancing beyond its colonial peripheral stance.

There was also a deepening chasm between the civil society and the state. Cor-ruption was on the rise and the nationalistic economy was only benefitting a narrow elite who would engage in private accumulation at the expense of the state. 1970s oil crisis had caused prices of necessities to rise on a level that less people could afford. The amount of aid allocated to social causes rose from 10% in the 1960s to over 50% by the end of the 1970s. (Moyo 2009)

This gave way to the emergence and growth of the third sector as many INGOs entered the countries and shifted developmental activities closer to the grass root level. The over all focus of aid in Africa moved more towards rural projects and so-cial issues such as ever increasing population and poverty. (Hoogvelt 2001)

In the 1980s the international development community started to officially recog-nize the need for more participatory approaches. Facilitating local dialogue and giving more emphasis to cultural factors started to gain ground among develop-ment initiatives (Servaes 1999). Servaes contrasted the until then prevailing mod-ernization and dependency theories of development with a new multiplicity para-digm, stating that there is no universal path to development, but “it is an integral, multidimensional dialectic process differing from country to country.” According to him every society was to be responsible for defining their own development strate-gy based on local needs. However, apparent failures in government-led moderni-sation efforts, debt crisis in 1970s and subsequent fiscal crises in developing coun-tries lead to Western lead neo-liberalism as a megatrend within international

de-velopment policy. The focus was shifting from poverty reduction more towards as-sisting developing world governments in adopting free market policies, such as cutting down on civil servants and privatizing state owned facilities (Moyo 2009).

Post-imperialist writers, such as Becker (in Hoogvelt 2001) have argued that during this period power-relations between nations became of lesser importance. Instead, power was shifted more and more to international corporate players, which con-tributed to the emergence of a new type of class division. Instead of socially divid-ed nation states, the world began to witness a global class partition, thus breaking away from the prevailing colonial core vs. periphery paradigm.

Kenya had experienced an industrial shift towards manufacturing in the 60s and 70s with multinational companies driving international capital and thus also national economy. As many other newly independent African states, Kenya was welcoming foreign investment. Though simultaneously trying to secure the vitality of Kenyan based firms via “Africanization” policies, such as the 1967 Trade Licensing Act, that forbade noncitizens from trading specified products in all non-urban areas and later restricting distribution exclusively to the Kenya National Trading Corporation. In the post colonial years the government also pushed education so that Africans would be more qualified and able to take the jobs until then held by Europeans (Nulty 2009).

In 1980 Kenya became one of the first African countries to accept IMF surveillance and to receive a World Bank structural adjustment loan. Widespread privatisation, liberalisation, de-regulation and commercialisation including the spread of com-mercial and private credit (also via microfinance) accelerated both Kenya’s and other East African countries’ transformation into neoliberal market societies. (Wiegratz & Cesnulyte 2015)

3.1.4 Informationalism & entrepreneurialism

Coming to the late 1980s and early 1990s, capitalism was once again restructuring itself. In a faster moving capitalist system prone to cyclical recessions, rigid mass-manufacture systems had become too slow for keeping up with the ever more globalized competition. New, more agile and lean, production methods were gain-ing ground.

The share of internationally traded manufactured goods in total world production had been rising steadily from the 70s till 90s. Thus, to gain access to new markets, capital needed to become more mobile and firms more efficient in their communi-cation. This need was answered by deregulation of markets and new innovation in information technology, which benefitted especially the high-tech sector and finan-cial corporations. (Castells 2010)

New information technology enabled integration of global financial markets and contributed to the disassociation of capital flows from national economies. In the 90s the continued integration of global markets and maximizing comparative ad-vantages of location again boosted productivity (and capitalists’ profits). The in-creasingly global competition created distortion as it made some companies, sec-tors, regions and ultimately countries more productive than others, rendering some of them obsolete. (Castells 2010)

According to Castells, a new social and technical division of labour has created a new information based industrial culture. The new economy, or Informationalism, entails a globally networked industrial model where knowledge is the main value-adding element, and where co-operation between global production units, partners and subcontractors is real-time.

The new economy meant even faster production cycles and thus greater invest-ment needs, as heightened competition equalled constant re-engineering and in-novation of new products and services. This increased speed has certainly affected

the way people work and live their lives. Long secure careers, serving the same large conglomerate throughout one’s working history have become more and more rare.

Informationalism according to Castells (2010) has also created a need for more short-term consultancy based and entrepreneurial employment. Individual compa-nies’ life spans are shorter but innovation and development happens in global knowledge networks, which creates powerful clusters of several smaller companies within the same domain. A good example of this was the late 90s dot.com boom which laid a foundation for the current information technology start-up phenome-non.

The Chinese have invested heavily in the African continent in the recent years, and Western critics are calling this a second wave of colonialism. Lee (2011) answers the criticism by pointing out that African countries are far from the top of countries receiving Chinese investment. In fact the US is number one and nobody claims that China is colonizing them. Perhaps the West indeed deserves to be called out a bit on their patronising attitude. It should be up to African governments and com-panies to decide whom they do business with. Leino (2015) aptly describes how African industry elite is busy doing business with the Chinese who expect a return on their investment, while the Western countries are “pouring cash in because of the good of humankind”…“Let them white boys help us out. We are too busy mak-ing money.” While the benefits in terms of buildmak-ing infrastructure and creatmak-ing jobs are eminent, the Chinese are criticised of importing much of the managerial em-ployees and higher skill demanding labour from the homeland (Lee 2011), employ-ing local Africans as wage labourers as was the case in the colonial period.

The economic successes and growth have injected new kind of economic optimism and inspired many prominent African business leaders to take development into their own hands. An example is the Nigerian business tycoon Tony Elumelu, who has coined the term ‘Africapitalism’ and calls fellow African businessmen to take

charge of the development of Africa via long-term investments in sectors that can create both economic prosperity and social wealth (Hirsch 2013).

The emergence of new communications technologies have also had a tremendous effect on development practice, enabling a whole new level of participatory, em-powering, democratizing, and sustainable modes of communication (McAnany 2012 a). McAnany suggests that the efficiency achieved in business via improved communications technologies is also translatable to striving for social benefit.

Although advances in communication technologies provide great liberties and act as catalyst to change, they have also brought about a greater responsibility in terms of content. Communication networks are prone to disseminating entirely new formats of propaganda with harmful intentions. Terrorist groups, such as Al Sha-baab in Kenya, are known to use sophisticated digital media campaigns for recruit-ing members.

McAnany (2012 a) criticises national leaders for the lack of direction and aware-ness of how the technological advances can be translated into social purposes or how people’s participation in the use of these technologies is crucial to improving their lives. Encouraging participation and making use of new technologies are man-ifested in the prevailing C4D and development paradigm of social entrepreneur-ship, which is discussed more in detail in chapter 3.4.

In the late 1990s, after a period of neo-liberal economic reforms, Kenyan govern-ment shifted priority more towards basic human needs, such as issues around wa-ter, sanitation, air pollution and land degradation, that were a potential hinder to development. For example in 1997 only 44 per cent of Kenyans had

ac-cess to basic sanitary facilities. (Nulty 2008)

Despite of the re-shifted focus and managing to extend compulsory primary educa-tion to almost all, Nulty however argues that Kenya has not taken enough aceduca-tion in the 21st century to ensure needed change. He criticizes the government of

regres-sive policies catering to the interests of the elite and middle-class, while neglecting the most vulnerable. For example demolition programs initiated by president Kibaki with the Ministry of Roads, Public Works and Housing have displaced thousands of people in Nairobi’s squatter settlements – without any form of compensation of-fered. According to Nulty (2008) Kibaki’s program came to an end thanks to public outcry from NGOs, which he claims are left in charge of the country’s social devel-opment.

The following chapter discusses Kenyan situation in the post millennium years.

3.2 Kenya in the 2000s and beyond

Modern day Kenya has established itself as the key driver of economic

co-operation in East Africa. With an annual GDP growth of around 5% for many con-secutive years, Kenya has been one of the fastest growing nations in sub-saharan Africa (The World Factbook and Odero et al. 2015). Major trade facilitation and in-frastructure investments include the Port of Mombasa, the improvement of the northern corridor road network and the construction of the Standard Gauge Rail-way to link Mombasa to Kampala. (Odero et al. 2015)

Coming to the 2010s the Kenyan government has committed to a national long-term development policy that aims to transform Kenya into a middle-income coun-try by 2030 (from its current lower middle-income status). The strategy is outlined in Kenya Vision 2030 with the aim of creating a “Globally Competitive and Pros-perous Nation with a High Quality of life by 2030” The strategy consists of three pillars, Economic, Social and Political, suggesting reforms and targets to all three areas respectively, for example achieving annual economic growth of 10%, invest-ing in cross-section of human and social welfare projects and programmes, as well as forwarding democratic and transparent governance. (Kenya Vision 2030)

3.2.1 Becoming an East African ICT hub

Kenya has traditionally relied heavily on agriculture and tourism. However, the new strategy intends to increase the variety of industries, and seek to grow the role of particularly Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and Digital Ser-vices.

The liberalization of Kenyan ICT market through the Kenya Communications Act of 1998 helped introduce a wide range of telecommunication services offered by local micro and small ICT companies as well as larger international firms (Wamuyu 2015). The 2009 arrival of under sea fibre optic Internet cables have enabled an Information and Communications Technology (ICT) policy, which intends to push the Kenyan economy more into technology and to become a major ICT outsourcing hub, rivalling typical IT outsourcing destinations like India and China.

The aim is to create up to 30,000 jobs for locals in the IT outsourcing sector. Companies like Kencall, Horizon, Ken-Tech and Techno Brain as well as other numerous ICT service providers are now competing of outsourcing work from in-dustrialized countries. (Kenya’s push to become an outsourcing hub)

Wamuyu (2015) however criticises large multinationals, often partially or fully owned and managed by foreigners, for putting smaller local ICT firms out of busi-ness by creating an environment impossible to compete in. IT conglomerates such as Google, IBM and Intel all have their regional offices in Kenya (Entrepreneurship in Kenya fact sheet).

3.2.2 Focus on growing entrepreneurs

Despite of the overpowering presence of multinationals, the faith in entrepreneur-ship is high and state lead initiatives have been introduced to encourage and coach prospecting entrepreneurs via developing their skills and informing them

about the steps of starting a business. For example, Enterprise Kenya, an initiative by Kenya’s Ministry of ICT and ICT Authority to support and build the Kenyan tech-nology entrepreneurship ecosystem by facilitating innovation, increasing aware-ness and helping to gain access to capital and other forms of entrepreneurial sup-port (Mulligan 2015).

Many companies and universities co-operate with small business centres offering entrepreneurship education and organising innovations competitions for students. Numerous accelerator programs and incubators such as Nailab and co-working space iHubhave stemmed from the global technology start-up movement and are examples of initiatives aiming to elevate local start-ups in Nairobi. Thus the nick-name Silicon Savannah.

3.2.3 Mobile innovation pioneers

Kenya is a poignant example of social change enabled by innovations in communi-cation technology. The country has embraced mobile communicommuni-cationswith an im-mense growth, going from only 17,000 mobile subscribers in 1999 to 30,5 million of voice/SMS and 12,3 million of mobile Internet subscribers in 2013 (Wamuyu 2015). In 2012, there were over 70 mobile phone subscriptions per 100 Kenyans whereas the sub-Saharan African average was 53 (Provost 2013).

Kenya’s reputation in mobile innovation is well known. Disruptive mobile inventions cover multiple sectors in Kenya, including mobile money, mobile health, mobile agriculture, m-commerce, and mobile banking applications. Many of these are un-known in the West. According to the Economist (2013) a third of Kenyan GDP is flowing through a mobile money-transfer system set up by a private telecommuni-cations company.

The digital space has enabled faster deployment of innovation and development of a budding start-up scene around mobile services. The world-famed M-Pesa mobile

payment service, as well as the mobile microfinance service M-Shwari and “pay-as-you-go” home solar systems provider M-Kopa, are examples of a highly devel-oped innovation infrastructure. Another example is the global mobile taxi service Uber, which is helping to create a more reliable and safe taxi network in Nairobi.

There are also examples of more peculiar social phenomenon, such as a whole village deciding to move location to a place in a higher altitude and thus better mo-bile connectivity (Impiö 2016).

3.2.4 Challenges

Despite of faster growing economy, poverty reduction in Kenya is still hindered by rampant corruption on a state level as well as within economic structures. Also, the economy’s reliance on primary goods with stagnated prices eats into the growth potential. (World Factbook) The traditionally lucrative tourism sector has been suf-fering greatly due to the recent terror attacks and threat.

The dominance of the agricultural sector, in which over 80% of Kenya’s population work at least part-time, is keeping the country from diversifying its industries. Yet, over 75% of all agricultural output comes from small-scale, rain-fed farming or live-stock production (World Factbook). Thus the grand masses are not benefitting from innovation and jobs within growing sectors, such as ICT. In a country of over 40 million people, with unemployment around 40%, creating a few thousand new jobs is nothing but a drop in the vast ocean. The real challenge for Kenya, is how to in-clude the informal sector - the millions of people making a meagre living out of odd jobs - as part of the national economic system.

Economic development of a country is often coinciding with the emergence of a strong middle class. African countries have, however been lagging behind in estab-lishing a middle class, and have thus only in the recent decade started to catch up with the rest of the developing world (Handley 2015). Nevertheless, income

ine-quality is still the widest in Sub Saharan countries when measured with the Gini-index1. South Africa leads the global income gap measure with the Gini coefficient above 60, whereas Kenya ranks right below the top 10, with the figure fluctuating around 45.

According to Handley (2015) the development of a middle class in Kenya has been slow due to a close connection of the bourgeoisie (the owning class) and a large and bureaucratic state apparatus. Himbara (in Handley 2015) describes the key alternative methods of accumulation: directorships in foreign companies and em-ployment as a civil servant, a traditionally very sought out position in Kenya.

The Economist (2013) argues that African people have the capital and technology available to improve their lives but Africa's entrepreneurs are often obstructed by inefficiencies like high level of bureaucracy. Bottom third countries in the World Bank's ease-of-business ranking are almost all in Africa. For example, according to The Economist (2013) Mombasa, East Africa's main port suffers from bottlenecks, and border and customs handling is still too costly and bureaucratic, which is a ma-jor hinder to trade.

In terms of rankings and numbers Kenya is still lightweight in global comparison. The GEI index, developed by the Global Entrepreneurship and Development (GEDI) Institute, is a way to measure the dynamism and quality of an entrepre-neurship ecosystem. Based on the information gathered from 30 dimensions of entrepreneurship (of which 15 institutional and 15 individual) the index illustrates “the entrepreneurial attitudes, abilities, and aspirations” of the entrepreneurial cli-mate at a national, regional and local level. (Ainsley, 2014) Kenya appears as 85th on the global and 5th in the regional level (The US ranks as 1st). Risk capital and tech sector get the highest score whereas start-up skills, risk acceptance, cultural

1 The GINI-index measures the income distribution of a country's residents as per their net income and helps to estimate the gap between the rich and the poor. On a scale between 0 and 100, 0 represents perfect equali-ty and 100 perfect inequaliequali-ty (Income Gini coefficient).

support and opportunity perception score lowest (GEDI - Kenya). Thus we can as-sume that lacking entrepreneurial skills and supporting infrastructure are holding Kenyans back when it comes to founding companies. Personal networks (family, friends) are still the main source of support (including funding) (Impiö 2016).

3.3 Capitalism’s effects in Kenya

While capitalism has gained ground as the global dominant economic system, it is necessary to examine its effects on the social and cultural aspects. A key question is: how does a capitalist world order affect people’s perceptions of social, political and cultural norms and values? And what kind of changes does this trigger in mor-al economies i.e. what people consider as acceptable and proper in earning a liv-ing and beliv-ing a member of a community?

3.3.1 Changes in moral economy

Handley (2015) argues that instead of responding to the incentives of the market, African key economic actors have been criticised of succumbing to pressures from the moral economy (or economy of affection). Wiegratz & Cesnulyte (2015) have studied the effects of adapting to a capitalist society on moral economies in Kenya and Uganda. They noticed that there has been a notable shift replacing a more community oriented “traditional African mind-set” with a more individualistic “every-one for themselves” thinking advocated largely by both governments as well as commercial media.

A facilitated capitalist discourse has diminished expectations towards the state and public provisions and instead endorsed individual ambition, determination

and enjoyment by becoming ‘modern’, tough and financially savvy, and taking care of oneself. Wiegratz & Cesnulyte (2015) point out that it is particularly questionable in a territory, where moral economies are traditionally based on priding oneself

over being a respectable community member and helping one’s family and neigh-bours, and continue by arguing that in a capitalist society taking care of and help-ing others becomes a subordinate priority to securhelp-ing material wellbehelp-ing. Changes in the material realities combined with growing economic insecurity influence changes in values that people perceive as important.

In their research case on Kenyan sex workers Wiegratz & Cesnulyte (2015) ob-served that when choosing between a secure stable income and judging

the respectability of said income, the financial aspect is emphasised and priori-tised. This is a good example of a monetized society with advanced processes of commodification that is bringing many life spheres, such as sex trade, to markets. The influence of a neo-liberal climate is normalizing professional groups that in the ‘old moral economy’ would be deemed as questionable. When communities start relying more on the spending of women who earn from prostitution, it be-comes framed as business as usual, which helps advance the moral restructuring process. Wiegratz & Cesnulyte cite the example of a Kenyan landlady that prefers renting rooms to women who sell sex, rather than families who are often less relia-ble rent payers.

3.3.2 Increasing informal sector

Another significant societal change in Kenya is the increase of the informal sector. According to Thieme (2015), an informal economy stems from the increased ab-sence of public services for the country’s majority living in material poverty, as the vast available workforce tries to make a living via capitalizing on this gap left by the state. Public services like sanitation, water and waste handling are examples of monetized services in Nairobi’s informal settlements.

The informal sector is growing due to unplanned urbanisation with fast growing informal settlements and neoliberal economic policies leading rising unemploy-ment. This touches especially the youth that find it increasingly difficult to get

for-mal employment. According to Thieme (2015) masses of young people are socially and politically vulnerable and in danger of being excluded and exploited. At the same time however, the youth are able to move fluidly and come up with creative ways of making a living. Though with often blurring the lines of what is legal versus illegal. Thus youth are “left to their own devices to create their own social worlds” where they shape their own alternative economies, rejecting formal institutions and authorities. In Nairobi slums the youth bond over friendships and place-based youth collectives forming networks to conduct economic activities in, matching those to the alternating economic realities and demands of their neighbourhood. (Thieme 2015)

The informal tactics of making a living, the so-called hustling, include a portfolio of money making activities and strategies connected with everyday street practices of “hanging about” (Thieme 2015) The hustlers – the micro entrepreneurs of sorts – who often call themselves businessmen and ladies, do small scale odd jobs, such as street vending, cleaning services, passenger and goods delivery, food prepara-tion and other everyday tasks as a service.

3.3.3 Environmental concerns

Kenya is famous for its lush and diverse natural habitat. Driving a capitalist econo-my is raising concern for environmental sustainability. More than 75% of Kenya’s population is directly dependent on land and natural resources for livelihood. And over 40% of the country’s GDP is derived from natural resources. Therefore sus-tainability topics and managing the effects of climate change are a high priority for the government. (Odero et al. 2015)

The legislation concerning the environment has been improved in the recent years and there are multiple regulations dedicated to the protection and sustainable management of natural resources. However, the level of quality and applicability of these laws has been disputed and the government has received plenty of critique

for lack of efficient national policies on natural resources management. Many lo-cals, among them climate and energy advocacy officer Kevin Kinusu of Hivos, a Dutch development organisation, exclaim that “the market forces and extreme hunger for a cash economy has been given dominance at the expense of our envi-ronmental and natural resource health.” (Gathigah 2014)

For example many rain-fed smallholder farms, that form a 75% majority of the total agricultural output, are encroaching on water catchment areas, which are threaten-ing the balance of the local ecosystems. Farmthreaten-ing land is scarce and natural areas are being converted to hard cash generating real estate projects.

(Gathigah 2014)

3.3.4 Capitalism and ethnicity

Ethnicity, or “tribalism” is a key concept in the discussion of African development and politics, being cited among many scholars as one of the biggest contributors to problems, such as instability, inequality, slow pace or failure of development as well as corruption. Modernist discourse has regarded “tribalism” as something to be defeated with development/modernization (Gĩthĩnji 2015). In this context it is interesting to examine what is the role of ethnicity in explaining economic prosperi-ty/poverty and distribution of resources?

In the past, prior to colonialism and the spread of capitalism, ethnic communities in Africa were formed around land ownership, they shared a language, culture as well as a primary form of production. The membership of an ethnic group determined ones share of resources, which were controlled by local ethnic elites. With the in-vasion of capitalism the resources, i.e. land became more scarce, thus raising its value and benefitting the elite. Individuals entering the capitalist sector in search of opportunities could however challenge the elite power (Gĩthĩnji 2015). This would suggest that capitalism could potentially dismantle existing ethnic power structures.

According Gĩthĩnji (2015), ethnic ties have been able to survive a capitalist disrup-tion due to networking, meaning the sharing of informadisrup-tion and assistance on op-portunities in the capitalist sector, as well as safety nets among members of an ethnic community. For example, migrants in the colonial motherlands often formed societies and clubs for helping each other settle and organise their livelihoods.

Recreation of ethnicity in post-colonial Africa was facilitated by two forms of capital-ist expansion, firstly the creation of territorial state that would entail multiple ethnici-ties within, and secondly the creation of a territory wide economy that was adminis-tered by an outsider, i.e. the colonial authority separate from the local economies. Local ethnic elites would be included into the national elite based on the number of individuals they represented (Gĩthĩnji 2015). In Kenya the Kikuyu, the largest tribe has until this day been holding the majority of positions of political and economic power.

Kanyinga (in Gĩthĩnji 2015) argues that “ethnic group representation shifts both with changes of power and ethnicity of the head of state and the shifting alliances that the head of state employs to maintain power”. According to Gĩthĩnji (2015) mem-bership in a large ethnic community is not beneficial for employment. The political and ethnic biases especially in the public sector can be either a barrier of a bridge to employment for a person. In Kenya a highly centralized government is the domi-nant employer and employees are appointed from the centre. Gĩthĩnji (2015) “All large ethnicities that have not had a president do badly.“

Kenya is a multi-ethnic country where more than 40 tribes as well as Asian and European immigrants have managed to live mostly in peace, excluding the 2007 hostilities stemming from the juxtaposition and suspected mischief of two compet-ing presidential candidates, opposition challenger Raila Odcompet-inga, a Luo and presi-dent elect Mwai Kibaki a Kikuyu, the largest tribe, who many feel has been ruling the political and economic sphere in Kenya for too long. (Ibelema 2014)

The lines of different ethnicities are not necessarily fixed, but cultural adaptation and mixing has also occurred in Kenya. Also the colonial regime is said to have created ethnic groups such as the Abaluhyia, Kalenjin and Mjikenda in Kenya to better control the population. Coinciding with the new constitution and the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in particular concerning the distribution of resources the number of ethnic communities demanding to be recognized al-most doubled from the officially counted 42 as different groups made claims on resources (Gĩthĩnji 2015).

Some scholars like to credit Kenyan Asians for the country’s economic achieve-ments. For example Himbara (in Chege 1998) claims this is due to commercial skills, determination and hard work, as well as Asians’ strong family units that sup-port entrepreneurialism. Whereas local Africans are said to lack business skills and culture, and are hindered by cultural norms that undermine entrepreneurial initia-tives. Chege (1998), however argues against this, crediting economic growth (as well as decline alike) a multi-racial effort.

According to Fafchamps (2000) market integration in Kenya can be largely ex-plained with network effects - the variables measuring socialization and information sharing – that often determine the access to trade and bank credit. Fafchamps (2000) argues that African and female entrepreneurs, who often runsmall, inexpe-rienced microenterprises, have been excluded from trade credit practices and thus many business opportunities due to lack of connections in relevant networks. At the same time however, the government’s attempts to restructure the ethnic repre-sentation of business networks may jeopardize the level of market sophistication, as this could mean a substantial loss of network capital (Fafchamps 2000). Thus hindering economic growth, as such capital would have to be re-gathered.

Gĩthĩnji (2015) argues that Kenya is “horizontally unequal and ethnicity plays an important part in obtaining economic opportunities at the top of the distribution”, and rather than correct historical inequalities, the Kenyan state has only managed to worsen the differences. The feared loss of network capital can partly explain

this. To provide people across different ethnicities equal access to opportunities, Kenyan political economy would require a large restructuring. There must be clear guidelines for the line ministries on how to deal with inequality as well as incentives to being a Kenyan citizen as opposed to an ethnic citizen (Gĩthĩnji 2015).

3.4 Entrepreneurialism and social entrepreneurship as the new development paradigms

This chapter looks at entrepreneurship and particularly social entrepreneurship as the current trend in tackling global development challenges; its opportunities, ex-amples, as well as a number of challenges.

International development organizations have been turning towards private sector practices in search for efficiency to answer the growing criticism for billions of “wasted” aid monies (Dolan & Roll 2013). Socially conscious but profit-making, demand instead of funding driven ventures have challenged aid-based develop-ment as the new developdevelop-ment paradigm (McAnany 2012 a).

More and more development programs are linked with promoting inclusive busi-ness and entrepreneurship as a means to take one’s economic destiny into one’s own hands, especially among the youth. Organising massive-scale events like the Global Entrepreneurship Summit, tell that promoting entrepreneurship as a means out of poverty (while also creating favourable business linkages) is high on the governmental agendas.

Thieme (2015) among many however, challenges entrepreneurship’s newly found role in development, arguing that “The Corporation” has become “an opportunistic agent of development as market-based approaches have mainstreamed claims to poverty alleviation, access to basic needs, and partnership with the entrepreneurial poor”. The reaction is two-fold: Some see this as immoral while others welcome it as a significant step up in efficiency (Thieme 2015). Thieme (2015) questions the

rationale of using business as a vehicle for development by arguing that new busi-ness development is challenging enough in low-income markets with highly infor-mal economic structures and rapidly growing, unplanned urban areas. “Businesses should stick to their fundamental competencies of growth through sustained in-crease of supply and demand, rather than hope to address the multi-dimensionality of poverty through enterprise.”

The ‘triple bottom line’ is another often mentioned concept that argues against Thieme and other critics. According to it businesses can stand on the three princi-ples of sustainability, i.e. be environmentally and socially responsible while also being profitable (Triple bottom line 2009). Though here the common critique is that whenever a company is in crisis and needs to react, environmental and social ben-efit usually have to be sacrificed for winning in profit. Reid & Griffith (2006) point out that the priority of the different alternative bottom lines differ from one social enterprise to another and there is no one model for organising those.

Dolan & Roll (2013) discuss the role of Base of The Pyramid (BoP) models in in-cluding informal economy and the poor as part of market capitalism or “making un-usable Africa un-usable to capitalism”. BoPs, or inclusive businesses, aim for a win-win situation whereby the poor get access to life-improving goods such as solar lanterns, sanitary pads, and cooking stoves at a reasonable price, and entrepre-neurs get to tap into new markets. However, Dolan & Roll argue that global corpo-rations may be taking advantage of BoP approaches in harnessing Africa’s under-productive, yet potentially dynamic entrepreneurs to serve the surplus extraction of transnational capital.

Defenders of more entrepreneurial approaches, such as Yunus (2010), claim that charity-based development can make people passive receivers. In contrast, social entrepreneurship treats its beneficiaries with greater personal dignity. Paying a fair price for the goods and services makes people self-reliant and active participants in the economic system, which Yunus says to be highly empowering. He however

acknowledges that there is a place for charity when people face a sudden loss, for example in times of a catastrophe and due to illnesses, or very young or old age.

3.4.1 Kenyan examples

Entrepreneurship is by no means a new concept in Kenya. As discussed above, a large informal sector has emerged with self-employed “hustlers” working on a number of small-scale ventures. Many companies and organisations are trying to come up with solutions on how to include the hustle economy as part of the formal economy. Many of these initiatives take the form of social entrepreneurship, such as the below examples.

Large multinational companies are partnering with NGOs and local governments for providing business skills training, internships, innovation competitions, grants and other types of support for cultivating small businesses. Creating jobs and fos-tering micro-entrepreneurship are common goals in the development discourse. Examples of multinational corporation supported development projects include the likes of Microsoft’s Tucoworks, an online employment and training platform for young people. Large Western state aid agencies such as USAID and the British DFID have also taken up entrepreneurship support programmes. For example, USAID has partnered with local organizations in training business and vocational skills, mentoring and supplying financial and employment linkages to disadvan-taged Nairobi youth. Another programme is called Yes Youth Can, where Kenyan youth across rural communities are supported to form savings and credit coopera-tives (SACCOs) that provide loans for youth entrepreneurship and microenterprise development. (Entrepreneurship in Kenya fact sheet)

Advances in communication technology are also enabling more and more varied C4D initiatives. International media and communications conglomerates like Face-book and Google are facilitating regional development via connectivity projects. For example, Facebook’s Internet.org aims to connect the world by making the Internet

(and most importantly Facebook and its network of services) more affordable and accessible to everyone (Internet.org). Google has contributed in digital develop-ment by helping make public transportation more accessible for Nairobi commuters by introducing a mapping service of official bus stops in the city (Mindock 2015). Local examples of successful social ICT enterprises include open source

crowdsourcing technology innovator Ushahidi that stems from mapping reports on violence during 2008 political turbulence, and Icow, an agricultural information ser-vice designed to help farmers enhance productivity.

3.4.2 Who is a social entrepreneur?

A social entrepreneur according to Martin and Ostberg (in McAnany 2012 b) is someone who has courage, drive to take direct action, creativity and capability to transform an unjust social situation. It is important for a social entrepreneur to facili-tate participation, listen and synthesise locally sourced information and efficiently communicate goals and results to benefit the project and its stakeholders. Com-munication element is thus particularly important for a social entrepreneur.

A social entrepreneur may create a social enterprise to solve a social problem via self-sustaining means. The concept has been popularized by social entrepreneur-ship pioneers Muhammad Yunus of the micro-lending institution Grameen bank, as well as Bill Drayton of the social change consultancy Ashoka Foundation. Accord-ing to Drayton (in McAnany 2012 a) creative problem solving has contributed to economic growth in the business world, and there should be no reason why it could not be applied to tackling social problems.

Social entrepreneurship is not to be mixed with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), which is something that companies may take up in order to seem like a “good neighbour” or a concerned member of the community. These are charitable activities, such as cleaning the environment, helping local elderly or children etc. (Yunus 2010).

Social entrepreneurs are motivated by the drive to solve people’s problems, a tradi-tional business by the desire to make money. Can these motivations be combined in a mutually beneficial way? According to Yunus (2010) governments can use so-cial enterprise partners in testing out solutions to different problems, empowering people in vulnerable positions as well as addressing problems faster and more effi-ciently.

Development projects of large funding institutions lack focus and continuity and often stumble on unnecessary bureaucracy. Thus they are less scalable and po-tentially lose in impact (McAnany 2012 b). A social enterprise strives to be self-sustaining and make profit that it can reinvest back to the business. Yunus (2010) brings forward the idea that foundations may invest in such social ventures. This kind of interlinking of business and non-profit actors is becoming more and more popular. Foundations may invest grant money into a social business entity that seeks to solve a problem by launching a business around a cause. This so-called Impact Investment model has received a lot of attention in development discus-sions.

Reid & Griffith (2006) emphasise the local perspective on social entrepreneurship. Social entrepreneurs often emerge from within local communities that include the main beneficiaries, clientele and employees of these social enterprises. Large insti-tutional funders cannot be on the driver’s seat but the creator of the social innova-tion must be able to control it to be able to grow the initiative and make the deci-sions based on their own needs.

Business ventures are more agile and scalable which leaves more room to trial and error type learning. Successful businesses often have repeatable models. An or-ganization typically stems from a local context and is able to grow and scale up, and the idea is then replicated for a new organization in a different context. This is a proven pattern in for example many online businesses. Development projects can potentially benefit from this type of agile approaches in applying new

innova-tion and technologies stemming from local peoples’ needs.

3.4.3 Problems with social entrepreneurship

According to Dey and Steyaert (2012) in contrast to traditional business entrepre-neurship, social entrepreneurship studies may not lend itself to enough critique and that it is perhaps too easily accepted as something innately good. Seen as an eco-nomically justified, often de-politicised “blueprint for dealing with societal problems” social entrepreneurship may become just a vehicle for providing quick fixes for the problems of the capitalist system without ever reaching to the deeper root causes. (Dey and Steyaert 2012) Similarly Reid & Griffith (2006) warn from succumbing to the common assumptions such as social entrepreneurship being more democratic and different in contrast to (inefficient) development efforts.

According to McAnany (2012 b) many people have had a hard time putting the words ‘social’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ in the same term. Dey and Steyaert (2012) also argue that some non-profit social enterprises are too focused on following a more business like “market logic” and strategies, which may be drawing attention and resources away from their social mission. According to Eikenberry (in Dey and Steyaert 2012) this may hamper the non-profit sector’s appeal towards donors as people get the message that their donations are not needed anymore. Overly rely-ing on economic thinkrely-ing in this context may result in understandrely-ing social entre-preneurship primarily as a means for correcting market failures and inefficient state lead social apparatus.

McAnany (2012 a) sees also so called development dependency as a potential hinder with impact investing. Bringing in outside institutional funding may discon-tinue the initiative when the money runs out, and there is no return model connect-ed to the business logic.

world. Key Performance Indicators are set to measure and drive the business’ op-erations towards fulfilling the set goals. In the social entrepreneurship world how-ever the metrics for quantifying and measuring impact, and thus the method for defining success, is not as clear (McAnany 2012 b). Social impact is a multidimen-sional topic and the effects may not be realised until a longer time has passed. This poses challenges for all stakeholders including the entrepreneurs, their opera-tional environment as well as investors who have to adjust their expectations of return for longer term.

Finally, the representation of social entrepreneurship often focuses around on high achieving individual social entrepreneurs who have given it all up to follow a higher calling. Dempsey and Sanders (in Dey and Steyaert 2012) argue that this is nor-malising a distorted understanding that in order to have a “right” to a moral sense of satisfaction from one’s work, one should sacrifice some level of personal emo-tional, social and physical well-being compensated with the motivation of meaning-fulness gained from working in the non-profit sector.

4. Analysis: Kenyan online media reporting on GES

The previous chapter outlined the development of the Kenyan capitalist narrative. The following empirical part of the thesis looks at online media reporting on the Global Entrepreneurship Summit, a high-level event with the purpose of promoting entrepreneurship for economic development. The chapter begins with a brief intro-duction to the Kenyan mediascape, with focus on online media, and continues with explaining the methodology, concluding with the analysis of the online text sample.

According to McAnany (2012 a) both communication technology, as well as con-tent are important elements for achieving social change. The focus of the Kenyan mainstream media has traditionally followed the changes in political climate from post-independence “Voice of Kenya” to becoming the state’s propaganda

depart-ment. The 1990s started a wave of liberalization and introduced new media agents into the industry. (Amutabi 2013)

According to Ogenga (2010) the political and economic environment, to an extent, still influences the manner in which the Kenyan media operates, and points out that the media’s interest is to maximize its owners’ profits “just like any other business organization in capitalism”. In the late 2000s, following the extensive reporting around the controversy of the 2007 elections, the government introduced further regulating legislation, as well as an organisation, the Media Council of Kenya, to act as self-regulative mechanism for the media (Ogenga 2010). This is prone to complicate the media’s strive to function as a watchdog in exposing government scandals and other issues of public interest.

Interactive communication platforms have enabled Kenyan media take a turn to-wards more citizen journalism and fight these limitations (Ogenga 2010). Internet access is not anymore a privilege of the few, but available to the masses via inex-pensive mobile handsets. Internet usage penetration stands at 70%. Kenyans are also active on social networks, with for example over 5 million Facebook users. (Internet World Stats)

Innovation in communication technology helps disseminate a wider variety of con-tent in the form of numerous online magazines, blogs and social media accounts. Blogging is becoming more and more popular and organised. As an example, sev-eral focused technology blogs such as Techweez and TechMoran write about global as well as local technology news. A community called The Bloggers Associ-ation of Kenya (BAKE) aims to empower and improve the quality of online content creation, and awards prominent blogs in an annual vote. (About BAKE)

Kenyans have also caught up on personal branding and cultivating opinion leader-ship. Savvy social media personalities are investigating, supplying information and facilitating conversation about multiple topics, including entrepreneurship. For ex-ample, local media outlet Capital Group features a video log series called Ask