© 2019 MA Healthcar

e Ltd

Abstract

Background: Persons with dementia may have severe physical and psychological symptoms at the

end of life. A therapy dog used in their care can provide comfort and relieve their anxiety. The dog handler guides the dog during the interaction with the patient Aim: To describe the impact of therapy dogs on people with dementia in the final stages of life from the perspective of the dog handler. Methods: Interviews were conducted and analysed using qualitative content analysis.

Findings: The dog provides comfort and relief through its presence and by responding to the

physical and emotional expressions of the dying person. Conclusions: Interactions with dogs were found to have a positive impact on persons with dementia and eased the symptoms associated with end of life according to the dog handlers.

Key words: l Animal-assisted therapy l Dementia l Palliative care l Therapy dog

I

n 2016, 47 million people had been diagnosed with dementia across the world, and this figure is expected to rise to 131 million by 2050 (World Alzheimer Report, 2016). Impairment in cognitive function is commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behaviour, or motivation for a patient with dementia (Van der Steen et al, 2014). As dementia is a progressive illness for which there is no cure, the disease should be recognised as a condition that ultimately requires palliative care (World Health Organization (WHO), 2018). Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life of the ill person and their family, and through its approach has a person-centred focus that aims to alleviate suffering and provide holistic care (WHO, 2011; Van der Steen et al, 2014).However, the behavioural and psychological symptoms associated with dementia are challenging in terms of the provision of effective symptom management (Husebo et al, 2011). In the later stages of the disease and towards the end of life, symptoms like depression, apathy, and agitation are common, as are physical issues like dysphagia, incontinence, myoclonus, and seizures

(Hugo and Ganguli, 2014). However, people with dementia are less likely to be referred to palliative care teams; they are prescribed fewer palliative care medications; they are unlikely to be assessed for existential needs before death; and they often lack adequate pain relief (Lillyman and Bruce, 2016). Dementia ultimately leads to a need for palliative care to mitigate symptoms that are physical and existential, and according to Hermans et al (2017), one of the many challenges in the provision of care is to relieve palliative symptoms that people with dementia may experience at the end of their life.

A person-centred perspective of healthcare is described as helping to create a positive care environment for the person with dementia, improving the caring climate, and reducing the stress level of caregivers (Edvardsson et al, 2014). Often pharmacological treatment, such as the use of neuroleptics, is administered to address a number of symptoms and behaviours; however, there are often side effects, and phar-macological treatments only provide temporary relief (Guthrie et al, 2010; Treloar et al, 2010; Huybrechts et al, 2012; Kales et al, 2012).

Previous research has shown that therapy

Dog handlers’ experiences of therapy

dogs’ impact on life near death for

persons with dementia

Anna Swall, Åsa Craftman, Åke Grundberg, Eleonor Wiklund,

Nina Väliaho and Carina Lundh Hagelin

Anna Swall

Senior lecturer, RN, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Health and Social Studies, Dalarna University, Sweden Åsa Craftman Senior lecturer, Department of Nursing Science, Sophiahemmet University, Sweden Åke Grundberg Senior lecturer, Department of Nursing Science, Sophiahemmet University, Sweden Eleonor Wiklund Ms in Nursing, Palliative Care, Lund, Sweden

Nina Väliaho

Ms in Nursing, Palliative Care Unit, Borås, Sweden

Carina Lundh Hagelin

Associate Professor, Senior Lecturer, RN, Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Sweden and Karolinska Institutet, Department of Neurobiology, Care Science and Society, Stockholm, Sweden

Correspondence to: Anna Swall

© 2019 MA Healthcar

e Ltd

dogs may function as a non-pharmacological alternative that works to decrease the challenging symptoms of dementia, including agitated behaviour, aggression and apathy (Nordgren and Engström, 2014; Martini de Oliveira et al, 2015; Swall et al, 2017; Scales, 2018). Therapy dogs have been shown to have a positive effect on the social behaviour of people with dementia and increase interaction with their environment, family and staff members (Bernabei et al, 2013; Swall et al, 2016) and decreased signs of depression (Perkins et al, 2008; Moretti et al, 2011; Mossello et al, 2011; Bernabei et al, 2013). Interaction with a therapy dog may also have a positive effect on the physical capabilities of people with dementia (Nordgren and Engström, 2012; Swall et al, 2014), alongside their memory and ability to express feelings and their overall quality of life (Swall et al, 2015).

When using a therapy dog in the care of people with dementia, the handler schedules visits based on the person’s needs, as assessed by a registered nurse or physisian, and guides the therapy dog team during its interaction with the person with dementia.

There has been a gradual increase in the use of therapy dogs in the care of older persons, which has resulted in a need for greater knowledge and research on the subject (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2014). The handler’s experiences with therapy dogs and persons with dementia near the end of life may contribute to an understanding as to how such therapy can be used. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the experience of dog handler’s visits to persons with dementia nearing the end of life.

Methods

Design and setting

A qualitative descriptive methodology with semi-structured interviews was conducted. The criterion for inclusion was that the participant had to be a dog handler with experience of dog therapy for dementia patients. The participants were enrolled through convenience sampling of suggested names of dog handlers from the founder of the therapy dog school. Potential participants were contacted and invited by phone or e-mail by the first author, who also provided information about the study. A written information sheet was attached to an invitation to participate. Interested participants contacted the first author to confirm their interest and to select an interview time and place; they also confirmed their participation with written informed consent.

Participants

A total of 11 dog handlers were asked to participate and seven handlers accepted and were eligible to participate. The handlers worked at seven municipal nursing homes in metropolitan areas in Sweden. They were all women and had worked for 3–7 years as handlers. Two were registered nurses, one was an occupational therapy assistant, and four were caregivers. They were aged between 43 and 65 and had worked in the care of older people for 20 to 37 years.

Data collection and analysis

The interviews were conducted and audiotaped by the first author (AS) between April and June 2014. These took place at the handler’s

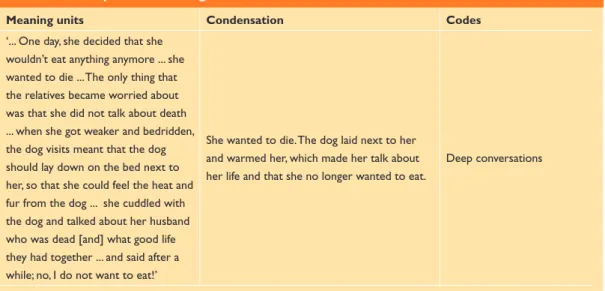

Meaning units Condensation Codes

‘... One day, she decided that she wouldn’t eat anything anymore ... she wanted to die ... The only thing that the relatives became worried about was that she did not talk about death ... when she got weaker and bedridden, the dog visits meant that the dog should lay down on the bed next to her, so that she could feel the heat and fur from the dog ... she cuddled with the dog and talked about her husband who was dead [and] what good life they had together ... and said after a while; no, I do not want to eat!’

She wanted to die. The dog laid next to her and warmed her, which made her talk about her life and that she no longer wanted to eat.

Deep conversations

Table 1. Example of meaning units, condensation and codes

© 2019 MA Healthcar

e Ltd

workplace. The interviews lasted between 22–96 minutes, and the participants were asked to talk about situations when they had visited people with dementia with their therapy dog. The answers were followed by probing questions.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and then analysed using qualitative content analysis, as described by Graneheim and Lundman (2004; 2017). The transcripts were read to gain a full understanding of the text. In the second part of the analysis, the text was divided into meaning units, since parts of text included sentences and phrases related to the aim of the study. The meaning units were then condensed and abstracted into codes (Table 1). A code can be assigned to discrete objects, events, and other phenomena connected to the text. Following this, the context (Graneheim and Lundman, 2004) became visible in the codes that emerged from the text.

The steps in this analysis were helpful in structuring the text and allowed for movement back and forth in the different levels of analysis. The codes were then compared for differences and similarities connected to the overall aim of the study, and then further grouped into four sub-themes and two overall themes (Table 2).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Board of Research Ethics (2010/220–31/1). The handlers were informed in both oral and written form about the aim of the study, how the interviews would be recorded, and how they could withdraw their participation at any time.

Interviewing people with dementia in the last phase of palliative care would not have been ethically acceptable and in light of this, the handlers of the dogs were interviewed for this study.

Findings

The results emerged in one theme and three sub-themes.

The presence of the dog and interaction

with the dog provide comfort and relief

at the end of life

The dog helps the person to ‘open up’

The presence of the dog created physical warmth, which helped people with dementia to ‘open up’ and talk about things that they otherwise did not mention in other interactions with healthcare professionals. Existential talk with the dog about approaching death was common, as well as

exploring the topic with the dog handler as communication was facilitated by the calming presence of the dog. The handlers described how the dog’s presence seemed to facilitate interaction and aid deeper conversations about life.

‘... many talk about their own future death ... a man with aphasia, he talked to the dog when he was approaching the end of his life: “Soon, I won’t be here anymore” ... and he did not look at me; he was talking to the dog the whole time …’ (Mandy)

When persons with dementia spoke to the dog, different topics related to their quality of life were raised: for example, that the person no longer wanted to eat, which the dog handlers interpreted as being a wish to die. Occasionally, persons talked about death with the handler as well, and they expressed their feelings.

However, persons with dementia also conversed only with the dog and expressed their feelings only to the dog—for example, their sadness and grief that their lives were ending. The handlers described in the study that they felt one of the reasons that persons with dementia shared deep, psychological and existential feelings and emotions with the dog, is that the conversation did not feel pressured as they did not have to answer any questions. They also knew that the information they shared with the dog would stay there.

The function of the dog as receiver and reliever The dog functioned as a ‘receiver and reliever’ of the emotional burden of a person with dementia in a way that the dog handler believed contributed to symptomatic relief, both physical and mental: for example, there was a reduction in pain and anxiety, and an increased sense of wellbeing for the person. The relief usually occurred when there was physical contact between the person and the dog.

Sub-themes Theme

●The dog helps the person open up

●The dog functions as a receiver and reliever ●The dog is responsive

and inspiring

●The presence of the dog and interaction with the dog provide comfort and relief at the end of life

© 2019 MA Healthcar

e Ltd

‘... and every time she opened her eyes and saw the dog, she said, “So wonderful” ... She had a good last night, because otherwise she had a lot of anxiety, but that night was good for her ...’ (Beth)

The handlers described how the presence of the dog with its warm body had not only a calming effect, which they believed increased the person’s sense of wellbeing, but also relieved many of the end-of-life symptoms.

They described aspects such as calmer breathing and reduced hyperventilation and anxiety, as well as reduced pain. The handlers also described one important role of the therapy dog, that it had a unique ability to be a comforting presence with the person with dementia and was able to reduce the anxiety that can be felt at the end of life:

‘... it (the dog) does everything from encouraging and stimulating to ... just being there … and a common thing in the final stage in life is the suppression of death anxiety ...’ (Ann)

Here the dog functions as a reliever and receiver, as described by the handlers, since it helps the person with dementia have peace of mind, which in turn allows the person to focus on positive things and not the difficult situation they find themselves in. The conversations between the person with dementia and the handler were prompted by the dog’s presence and were about life at present, life that was lived, and future life, which often focused on death.

The dog is responsive and inspiring

The handlers described how the dog was responsive and how there was a connection between it and the dying person. Often, interactions with the dog made situations positive, and the dog’s responsiveness acknowledged the person with dementia and helped them focus on the present.

Handlers also described situations in which the presence of the dog had a physical effect on the person: for example, some who had not spoken for a while and who had been lying in bed for some time suddenly opened their eyes when the dog was close. Furthermore, the handlers described how the presence of the dog led to a shift in focus from the person with dementia’s situation to the dog and its wellbeing. One woman on her last night alive was focused on the dog’s comfort, which was demonstrated by her asking the staff to shut the window as she was

concerned that the dog was cold.

Dog handlers also described other patients who suddenly wanted to sit up or eat despite earlier unconsciousness. In these situations, the handler knew that the person and the dog often had a history of visits together.

‘... we had a man ... he was approaching death ... dogs had been a big part of his life ... the dog climbed up so that it was within sight ... his daughter said: Do you see the dog ...? And then he opened his eyes and then he saw the dog … he had a smile all over his face, and then he fell asleep ... the third time he woke up and smiled ... he started to pat the dog ... the physiothera-pist and the daughter were shocked ... he had not used that arm for a very long time ... he died the following morning.’(Christine)

‘The caregiver contacted me ... “I think it is close now, that (name of a lady) is going to pass away ... and I’m just wondering if you could come up with the dog because she has developed a relationship with the dog. She is unconscious, but she may still sense that the dog is close by” ... the dog put its head on the bed beside her ...Then suddenly she opened her eyes and said “Is my dog here? My cousin? ... yes…you!” And then she began moving and wanted to sit up in bed to have a snack ...’ (Nelly)

The dog handlers described their own personal feelings when people with dementia showed a desire to live; they found a sense of meaningfulness in the moment with the dog that motivated and inspired them. It seemed like the dog’s responsiveness gave persons with dementia the energy and motivation to become more physically active—that is to say, despite being close to death, to use parts of their body that they usually did not use.

Discussion

In this study, one overarching theme was clear: that the presence of the dog and the interaction with the dog provide comfort and relief at the end of life. These results suggest that the presence of a therapy dog stimulates persons with dementia in a way that allows them to communicate when habitually they have difficulties expressing themselves. The dog was perceived to be a collocutor in a mutual conversation in which emotions, difficult questions, and existential feelings were expressed. Similar findings are voiced by Krause-Parello and Gulick et al (2013): the

❛

The third time

he woke up and

smiled ... he

started to pat

the dog ... the

physiotherapist

and the

daughter were

shocked ... he

had not used

that arm for a

very long time❜

© 2019 MA Healthcar

e Ltd

presence of a dog led to profound talks about life, concerns, and existential thoughts. In this study, the handlers felt that the dog’s presence affected the person as a whole: physical benefits were thought to be pain relief; emotional benefits were being able to express emotions and discuss difficult topics; the social benefit was friendship with the dog; and the spiritual benefits were the thoughts about the difficult but important topics persons with dementia raised in response to having the dog around.

Pain at a late stage of life is common. To reduce pain, opioids are commonly used. However, these medications have a number of side effects (Thomas et al, 2008). Patients with dementia can be under-treated with pain relief because of symptoms of dementia that overshadow symptoms of pain (Lillyman and Bruce, 2016). In this study, the handlers felt that some of the persons with dementia who received therapy dog visits experienced less pain when the dog was physically close to them. The dog seemed to lessen their pain and worries, and to decrease this part of their suffering. Engelman (2013) found that a dog could both distract and relax the person, which in turn decreased the level of pain they experienced.

Interaction with the therapy dog is described in previous studies by Swall et al (2016; 2017). Interactions with the dog brought with them memories from the past and present, while inspiring the person to exhibit sorrow and joy to the dog. In the present study’s findings, the handlers described how the dog did not require anything from the person with dementia. The findings show that comfort was found in the undemanding relationship with the dog: the person directed the situation in ways they were comfortable with, and they could care for the dog by giving it treats, petting it, or brushing it. This allowed the persons with dementia to behave in a way that allowed them to forget that they have a reduced capacity to do the things that they used to enjoy.

Some persons with dementia were able to shift focus from their difficulties of nearing the end of life to the dog and the dog’s wellbeing. This could mean that the relationship with the dog could give comfort (Sand and Strang, 2013). Furthermore, Swall et al (2016) found that the therapy dog’s visits seemed to help those with dementia forget their disease, at least for the moment, as they engaged with the dog and its wellbeing.

Yet for some, the presence of a dog seemed to have little effect. The handlers described how the sense of anxiety in some persons with dementia

was strong and how they often closed themselves off. One aspect to consider is whether these persons suffer from an anxiety that is so strong that they can barely cope at the end of life, causing them to be unable to interact with the environment, the dog included. Although Gibbons et al (2006) found that anxiety disorders in people with dementia are commonplace, the presence of a dog did seem to reduce the level of anxiety in some patients.

Methodological considerations

Data were collected by way of semi-structured interviews with handlers from diverse professions and workplaces who had received the same training at the therapy dog school: this can be seen as a strength as they were able to apply the therapy in the same manner.

The trustworthiness of the study was supported by the cooperation of authors during the data analysis. While the first author (AS) took the lead, the last author (CL) read and discussed the steps of the analysis. The four remaining authors (ÅC, ÅG, EW, NV) then reviewed the analysis, and when opinions differed, these were discussed until a consensus was reached. The opportunity to move back and forth between the different levels of the analysis and the original data was considered important in terms of increasing the trustwor-thiness of the study.

The interviews with the seven handlers took place where they worked. Only two of the handlers were colleagues at the same nursing home. This can be seen as a strength considering how colleagues and working climates can affect one another. The dog visit procedures and the prescriptions may vary from team to team. It is possible that the handlers’ opinions about the dog and its presence may be mostly positive due to the handlers’ close relationship with their dogs and that as a result, negative and less positive situations were not brought up. However, questions about less positive experiences were also asked during interviews to mitigate this.

The results demonstrate the handlers’ experiences of observed interaction between the therapy dog and the person with dementia at the end of life.

It is possible that the dog handlers’ experiences do not fully reflect what the person with dementia experiences in these situations: this must be taken into consideration. Interviewing persons with dementia at the end of life is often not possible, and as a result of this, there is little research on persons with

© 2019 MA Healthcar

e Ltd

dementia during palliative care. As such, further research is needed and this study contributes to this important area of care.

Conclusion

Interactions with the therapy dog were found to have a positive impact on persons with dementia and their situation according to the handlers; therefore, the use of therapy dogs may be beneficial for many healthcare institutions. According to the handlers, the dog’s physical closeness seemed to have a calming effect, and the persons with dementia appeared healthier while in the presence of the dog, with experiencing some relief from end-of-life symptoms and associated anxiety. Studies are needed to increase knowledge in the field and to consider the therapy dog as a nursing intervention and in some cases a complement to non-pharmacological treatment in the palliative phase for persons with dementia.

Declaration of interests: the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement: this work was supported by the Agria Djurförsäkring, Demensförbundet, Sophiahemmet University, Sophiahemmet Research Foundation, Queen Silvia Fund for Education and Research, Kung Gustav V’s and Queen Victoria’s Foundation, Ragnhild and Einar Lundström Foundation, Svenska Kennelklubben and Dalarna University

Bernabei V, De Ronchi D, La Ferla T et al. Animal-assisted interventions for elderly patients affected by dementia or psychiatric disorders: a review. J Psychiat Res. 2013; 47(6):762–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jpsychires.2012.12.014

Edvardsson D, Sandman PO, Borell L. Implementing national guidelines for person-centred care of people with dementia in residential aged care: effects on perceived person-centredness, staff strain, and stress of conscience. Internat Psychoger. 2014; 26(7):1171– 1179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214000258 Engelman SR. Palliative care and use of animal-assisted

therapy. Omega (Westport). 2013; 67(1–2):63–67. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.67.1-2.g

Gibbons LE, Teri L, Logsdon RG, McCurry SM. (2006). Assessment of anxiety in dementia: an investigation into the association of different methods of measurement. J Geriat Psych Neurol. 2006; 19(4):202–208. https://doi.

org/10.1177%2F0891988706292758

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Methodological challanges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurs Educat Today. 2017; 56(9): 29-34.

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurs Educat Today. 2004; 24(2):105–112. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

Guthrie B, Clark SA, McCowan C. The burden of

●

IJPN

tia: a population database study. Age Ageing. 2010; 39(5):637–642. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/ afq090

Hermans K, Cohen J, Spruytte N, Van Audenhove C, Declercq A. Palliative care needs and symptoms of nursing home residents with and without dementia: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017; 17(10):1501–1507. https://doi.org/10.1111/ ggi.12903

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002 Hugo J, Ganguli M. Dementia and cognitive

impair-ment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014; 30(3):421–42. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.001

Husebo BS, Ballard C, Sandvik R, Nilsen OB, Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2011; 343: https://doi-org/10.1136/bmj.d4065

Huybrechts K, Gerhard T, Crystal S et al. Differential risk of death in older residents in nursing homes prescribed specific antipsychotic drugs: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2012; 344:e977. http://dx. doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e977

Kales HC, Kim HM, Zivin K et al. Risk of mortality among individual antipsychotics in patients with dementia. Am J Psych. 2012; 169(1):71–79. https:// doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030347 Krause-Parello CA, Gulick EE. Situational factors

related to loneliness and loss over time among older pet owners. West J Nurs Res. 2013; 35(7):905–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945913480567 Lillyman S, Bruce M. Palliative care for people with

dementia: a literature review. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2016; 22(2):76–81. https://doi.org/10.12968/

ijpn.2016.22.2.76

Martini de Oliveira A, Radanovic M, Cotting Homem de Mello P et al. Nonpharmacological Interventions to reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2015; 218980. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/218980 Moretti F, De Rochi D, Bernabei V et al. Pet therapy in

elderly patients with mental illness. Psychogeriat. 2011; 11(2):125–129. https://doi.

org/10.1111/j.1479-8301.2010.00329.x

Mossello E, Ridolfi A, Mello AM et al. Animal-assisted activity and emotional status of patients with Alzheimer’s disease in day care. Int Psychogeriat. 2011; 23(6):899–905. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S1041610211000226

National Board of Health and Welfare. Therapy dog for older persons in municipal care. 2014. https://tinyurl. com/ybl3djn7 (accessed 30th January 2019) (article in Swedish)

Nordgren L, Engström G. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on behavioural and/or psychological symptoms in dementia: a case report. Am J Alzhei-mers Dis Other Demen. 2012; 27(8):625–632. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1533317512464117.

Nordgren L, Engström G. Effects of dog-assisted intervention on behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Nurs Older People. 2014; 26(3):31–8. https://doi.org/10.7748/

nop2014.03.26.3.31.e517.

Perkins J, Bartlett H, Travers C, Rand J. Dog-assisted therapy for older people with dementia: a review. Australas J Ageing. 2008; 27:177–182. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00317.x

Sand L, Strang P. When death challenges life—about existential crisis and coping in palliative care (Närdöden utmanar livet—Om existentiell kris och coping i palliativ vård). (ss155–163). Stockholm: Natur and kultur; 2013

Scales K, Zimmerman S, Miller SK. Evidence-based nonpharmacological practices to address behavioral

© 2019 MA Healthcar

e Ltd

and psychological symptoms of dementia. Gerontol. 2018; 58(1):88–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/ gnx167

Swall A, Ebbeskog B, Lundh Hagelin C, Fagerberg I. ‘Bringing respite in the burden of illness’—Dog handlers experience of visiting older persons with dementia together with a therapy dog. J Clinic Nurs. 2016; 25(15–16):2223–2231. https://doi.

org/10.1111/jocn.13261

Swall A, Ebbeskog B, Lundh Hagelin C, Fagerberg I. Can therapy dogs evoke awareness of one’s past and present life in persons with Alzheimer’s disease? J Older People Nurs. 2015; 10(2):84–93. https://doi. org/0.1111/opn.12053

Swall A, Ebbeskog B, Lundh Hagelin C, Fagerberg I. Stepping out of the shadows of alzheimer’s disease: a phenomenological hermeneutic study of older people with alzheimer’s disease caring for a therapy dog. Int J Qualitat Studies Health Well-being. 2017; 12(1): 1347013. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2017.13 47013

Swall A, Fagerberg I, Ebbeskog B, Lundh Hagelin C. A therapy dog’s impact on daytime activity and night-time sleep for older persons with Alzheimer’s disease—a case study. J Clin Nurs Studies. 2014;

https://doi.org/10.5430/cns.v2n4p80

Thomas JR, Cooney GA, Slatkin NE. Palliative care and pain: new strategies for managing opioid bowel dysfunction. J Palliat Med. 2008; 11(1):S21–2. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2008.9839.supp Treloar A, Crugel M, Prasanna A et al. Ethical

dilem-mas: Should antipsychotics ever be prescribed for people with dementia? Br J Psych. 2010; 197(2):88– 90. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076307 Van der Steen J, Radbruch L, Hertogh C et al. White

paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med. 2014; 28(3):197–209. https://doi. org/10.1177/0269216313493685

World Alzheimer Report. Improving healthcare for people living with dementia. 2016. https://tinyurl. com/y99ffoj6 (accessed 28th January 2019) World Health Organization. Palliative care for older

people. 2011. https://tinyurl.com/y7g7v8cg (accessed 28th January 2019)

World Health Organization. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide World Health Organization. 2018. https://tinyurl.com/y7h9e6mm (accessed 28th January 2019)

Key points

● Research has shown that therapy dogs may function as a non-pharmacological alternative that works to decrease the challenging symptoms of dementia, including agitated behaviour, aggression and apathy

● This study has shown that interactions with therapy dogs provide comfort and relief at the end of life for persons with dementia

● The presence of a therapy dog stimulates persons with dementia in a way that allows them to communicate, when habitually they have difficulties expressing themselves