ensK Botai

Utgiven rav

SvensKa BotanisKa Föreningen

Redigerad av

STEN AHLNER

BAND 60

1966

HÄFTE 4

SVENSKA BOTANISKA FÖRENINGENS

styrelse och redaktionskommitté år 1966.

Styrelse:

J. A. NANNFELDT, ordförande; E. HULTÉN, v. ordförande; L. BRUNKE- NER, sekreterare; S. AHLNER, redaktör och ansvarig utgivare av tidskriften; V. BJÖRKLUND, skattmästare; N. FRIES, G. HARLING, T. HEMBERG,

E. v. KRUSENSTJERNA, T. NORLINDH, W. RASCH, H. WEIMARCK.

Redaktionskommitté:

G. E. DU RIETZ, F. FAGERLIND, N. FRIES, E. HULTÉN, J. A. NANNFELDT, C. O. TAMM.

SVENSK BOTANISK TIDSKRIFT utkommer med fyra häften årligen.

Prenumerationsavgiften (för personer, som ej tillhöra Svenska Botaniska Föreningen) är 45 kronor. Svenska och utländska bokhandlare kunna direkt hos föreningen erhålla tidskriften till samma pris.

Medlemsavgiften, för vilken även tidskriften erhålles, är 35 kronor för medlemmar, bosatta i Sverige, Danmark, Finland, Island och Norge, och kan insättas på föreningens postgirokonto 29 86 eller översändas på annat sätt. Giroblankett för inbetalning av påföljande års medlemsavgift åt följer häfte nr 4. Har inbetalning ej skett före utgivandet av häfte nr 1, utsändes detta mot postförskott, varvid porto debiteras. Medlemmar er hålla i mån av tillgång tidigare årgångar av tidskriften till ett pris av 24 kronor per årgång.

Generalregister över de första 40 årgångarna finnas nu tillgängliga.

SVENSK BOTANISK TIDSKRIFT, edited by Svenska Botaniska Föreningen (The Swedish Botanical Society), is issued quarterly.

An annual fee of 45 Sw. Kr., which includes the journal, applies to mem bers outside Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Norway. The jour nal is available to booksellers for the same amount. Back volumes are available to members at 24 Sw. Kr. according to supply.

A general index, in two parts, to Volumes 1-40 is now available.

ON THE OCCUR HENCE OF YEASTS IN AN ESTUARY

OFF TIIE SWEDISH WESTCOAST.

RY

BIRGITTA NORKRANS.

Marine Botanical Institute, University of Göteborg, Sweden.

Since 1945, a series of studies on the quantitative distribution of marine microorganisms has been published by Russian microbio logists. These investigations which embrace the waters of the Black Sea, the Sea of Okhotsk, the Arctic Sea, and parts of the Pacific Ocean, have been summarized by Kriss (1961). Studies on the yeast

flora in the Indian Ocean have been published by Biiat & Kach-

walla (1955). In 1946 Zobell gave a review for early notes on

yeasts in the sea. These publications cover more or less the investiga tions on yeasts in seawater that have been carried out in recent times until 1960. The situation prevailing at that time in this field is sum marized by Johnsson & Sparrow (1961) in their comprehensive

review “Fungi in Oceans and Estuaries” by the words: “it is substan tially true that knowledge of marine yeasts is at a level somewhat comparable to that of marine fungi prior to 1900”.

Since 1960, however, our knowledge of the occurrence, distribu tion, and taxanomy of marine yeasts has been extended by the work of a number of independent teams. Thus yeasts in the south tempe rate and subtropical regions have been studied: in the Pacific off southern California by inter alia Uden & Zobell(1962) and Uden &

Castelo-Branco (1963), in the western and eastern Atlantic by

Fell el al. (1960), Capriotti (1962) and by Taysi & Uden (1964),

whilst Siepmann & Hönk (1962) have presented data about the

North Atlantic.

The present investigation has been carried out in the Kungsbacka fjorden. This is part of the Kattegatt, and is situated in the north temperate zone. The purpose of this work was to study the occurrence of yeasts in this region, to estimate, approximatively, their numbers relative to the total population of the heterotrophic microflora, and

Su. liot. Tidskr., GO (I960): 4

GSBACKA 5r29' Onsala + 0262 Gottflkttr * Jäven >Ramnö( ;^4 I ordskär . (0278 * s JlållsimcLsii.

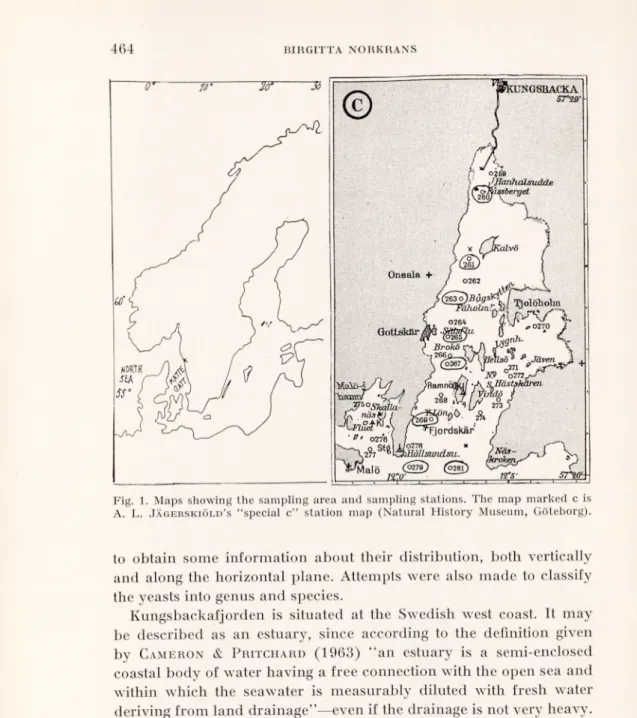

C-Fig. 1. Maps showing the sampling area and sampling stations. The map marked c is A. L. Jägerskiöld’s “special c” station map (Natural History Museum, Göteborg).

to obtain some information about their distribution, both vertically and along the horizontal plane. Attempts were also made to classify the yeasts into genus and species.

Kungsbackafjorden is situated at the Swedish west coast. It may be described as an estuary, since according to the definition given by Cameron & Pritchard (1963) “an estuary is a semi-enclosed coastal body of water having a free connection with the open sea and within which the seawater is measurably diluted with fresh water deriving from land drainage”—even if the drainage is not very heavy. Extensive zoological studies by A. L. Jägerskiöld in the Skagerack-

Kattegatt region during the years 1922-39 included also this area. The map C (Fig. 1) is just a part of A. L. Jägerskiöld’s station map,

the “Special C” for this area, where his sampling stations are given. In the autumn of 1963, a marine zoological group from Göteborg instituted a reinvestigation of Kungsbackafjorden and decided to

exploit in part the station system used by Jägerskiöld. By the courtesy of the group, the present author has been given the oppor tunity of getting samples from some of the sampling stations of the western part of the estuary, for which tanks are due to Fil. mag.

Leif Gustafsson and Fil. mag. Ingemar Olsson. The eight stations

concerned, all located along the deepest part of the estuary, are designated by the numbers 260, 261, 263, 265, 267, 269, 279 and 281 on the map. The sites originally known as 260 and 261 have been slightly changed, and are now designated by 260A and 261A2, respectively. They are marked on the map by a cross, the other sampling stations being indicated by a circle.

Methods.

Samples were collected in sterile flasks with a Valås-sampler (Swedish patent no. 177629 produced by Valås Mekaniska Verkstad, Ljungskile, Sweden). The 600 ml samples were run through sterile Co5 membrane filters (Göttingen). After filtration, each filter was suspended in 10 ml of sterile sea water, thus giving a 60 fold concentration of the microorganisms. Generally, one ml of the concentrated suspension was plated for yeast determinations, but for determinations of the total microflora samples were plated also after suitable serial dilutions. All samples were processed within the day of collection. To reduce the injuring effect of the plating procedure to a minimum, all the steps were performed as quickly as possible and the molten nutrient agar was precooled to 42°C before plating and not more than 10 ml per plate was used (cf. Gunkel 1961).

The isolation media used had the following composition:

1. Glucose 1.0 g, Bacto yeast-extract 0.1 g, agar 18.0 g, aged seawater 1000 ml (Medium GYA). pH about 6.0.

2. Glucose 10.0 g, malt-extract 3.0 g, Bacto yeast-extract 3.0 g, Bacto- pepton 5.0 g, agar 15.0 g, aged sea-water 1000 ml (Wickerham 1951, Medium \VA). pH about 6.0.

3. Glucose 5.0 g, MgS04-7H20 0.5 g, KH2P04 0.5 g, NH4C1 0.5 g, ferri- citrate solution (1% ferricitrate, 0.64% citric acid) 1 ml, malt-extract 5.0 g, agar 15.0 g, distilled water 1000 ml (“Hagemmalt-agar” = Medium HA). pH about 5.0.

4. Meat-extract (Liebig) 5.0 g, Bacto-pepton 10.0 g, NaCl 5.0 g, agar 15.0 g, distilled water 1000 ml (Medium MPA). pH about 7.0.

Medium HA, having a low pH value was designed preferentially for fungal growth, the MPA medium for bacterial growth.

Plates were run in duplicate and incubated either at 25°C for 3-14 days or att 14°C for 7-20 days before the colonies were counted. The total number of colonies (T) was counted as well as the number of yeast colonies (Y), distinguished by macroscopic and microscopic morphology. Colonies of mycelium-forming fungi (M) and actinomycetes (A) are on some occasions presented separately in the Tables.

From the Tables, the number of bacteria colonies are obtained by subtract ing the number of yeast colonies and mycelium-forming fungi from the total number of microorganisms. For samples and media giving T-values >10,000/1, the number of yeasts and mycelium-forming fungi can not be given with accuracy. In these cases, the fungal values have been either omitted entirely in the Tables at low fungal density or—at higher density of fungal flora—given within brackets.

The absolute number of bacteria may be somewhat too low since the MPA may be a too heavy medium for some marine occurring bacteria. The relations between the numbers at the different sites and dates are, however, very likely correct. Though no statistics were compiled, the Tables enable us to express an opinion on the yeast content of the different samples examined and to compare them with one another.

For the identification and classification of the different yeast strains, single-colony isolates were tested according to the diagnostic procedures given in detail by Kreger-van Rij (1964) and Lodder & Kreger-van

Rij (1952). The procedures include morphology tests in malt-extract solu tion and slide cultures with rice and potatoe agar, sporulation tests on a number of media known to promote spore formation and—if necessary—use of known mating types. In addition tests were performed for fermentation capacity and ability to assimilate carbon compounds. The latter was tested by an auxanographic method in “short” or—if necessary—in “long” runs, involving 30 different carbon compounds. In cases of negative results with the auxanographic method, the tests were repeated in liquid media. The capacities for nitrate assimilation, arbutin splitting and starch formation were also tested. In addition, the lipolytic activity for the strains was tested by a method given by Sierra (1956).

Results and Discussion.

A total of 80 samples were collected from eight stations during 12 days between February 1964 and July 1965. The samples were examined for the aerobic heterotrophic microflora with special attention paid to the yeast flora. The results are collected and pre sented in Tables I—III.

Yeast occurrence. The tests showed that yeasts do occur in this water area, though only 48 of the samples constituting 60 % of the samples examined were yeast positive.

Since the largest number of fungal colonies were obtained on HA and GYA media (see Tables I and III) these values represent the most probable number for yeasts (Y) and mycelium-forming fungi (M) occurring in the samples concerned. Sometimes, larger values for mycelium-forming fungi were obtained on HA than on GYA, whereas

Table I. Minimum numbers of aerobic colony-forming microorga

nisms per 1000 ml of water.

The data refer to samples taken at station 267 on two different dates at various vertical casts. The numbers are calculated from counts of three different media i.e. glucose- yeast agar (GYA), "Hagem”-malt agar (HA) and meat-pepton agar (MPA). Total number (T), number of yeasts (Y), mycelium-forming fungi (M) and actinomycetes (A).

S = surface.

6 March 1964 9 April 1964

Depth GYA HA GY A MPA

T Y M A T Y M A T Y T 267 S 17,000 (170) (200) (300) 6,000 66 1,000 0 55,000 (33) 160,000 1 m 85,000 2,400,000 3 m 64,000 (230) (70) (33) 433 233 200 0 5 m 30,000 (230) (270) (0) 933 233 400 0 19,000 42,000 8 in 48,000 (260) (270) (133) 600 67 400 0 14-15 m 10,000 0 67 0 100 67 0 0 192 96 1,000 20 m 3,000 0 33,000

the contrary relationship was obtained for yeasts, probably reflec ting their generally higher pH tolerance. Great differences, however, were not observed. The largest total number of colonies formed (T) were generally obtained on MPA (see Tables T—III) and represent approximately the same as the number of bacteria colonies. The quantitative value obtained in a given sample for a particular group of microorganisms on that medium which gave the largest number, will be referred to as the “maximum number”. The Mmax generally are higher than the Ymax, for the positive samples ranging from 17 to 510. However, the numbers of both fungal groups were always small in comparison with the bacterial number obtained from Tmax values and running up to millions. The value of 2,400,000 (Table 1, 9 April, 1 m), seems to be caused by an incidentally intense occur rence of Cgtophaga sp.; other high Tmax values (see Tables III and VI) will be discussed later.

Vertical distribution. In order to examine the probabilities for a regular vertical distribution of yeasts in this seemingly random distribution, the material was tentatively grouped in a way that can be seen in Fable IYa. To classify the material into surface and bottom samples seems easily motivated, whereas the other three apparently

T

a

b

le

II

.

M

in

im

u

m

n

u

m

b

er

s

o fae

ro

b

ic

co

lo

n

y

-f

o

rm

in

g

m

ic

ro

o

rg

an

is

m

s

p

er

1 0 0 0m

l

o

f

w

at

er

.

O CD SS § g St p t-T3 c p 4S p 3 —< O Cd a> . p ^ £ Ph « g, £ & £ üß P cd . P o P O C3 “ft«1 c« ' || S « <DC/3 id £ ^ •£ T3 §, <3 § 'So c/7 < P JS» t-. .£ 01 2 ÜC c 01 cd oi O» 01 c 01 £ 5 p p o_> %- D P £ P CJ a> 1^ tH 00 C « os c SX-o T3 “ C Ch ^ * O ^ >1 oSS ^ as ; C 03 , O ■p c/53 cd O, -«•a •o „ <u tu ■S J3 H ~Se. Bot. Tidsk,

27 N o v . G Y A 6 7 17 17 17 >■< 0 0 33 17 H 4 ,5 0 0 2 1 ,5 0 0 10 ,0 0 0 67 500 100 4 N o v . GY A 83 167 0 50 333 0 17 11 7 >" 0 0 50 17 5 1 0 0 17 0 H 1 ,0 0 0 1 ,6 8 0 2 ,8 3 0 1 ,0 0 0 1 ,4 0 0 700 18 3 2 ,0 7 0 30 S ep t. G Y A <■< 1 3 3 1 3 3 0 33 33 0 0 K* 0 33 33 33 0 0 0 H 1, 25 0 3 .0 0 0 4 .0 0 0 1 .0 0 0 6 ,0 0 0 750 3 ,0 0 0 2 8 A p ril 19 64 MPA H 28 ,0 0 0 2 0 ,0 0 0 2 1 0 ,0 0 0 5 8 .0 0 0 1 1 3 ,0 0 0 4 6 .0 0 0 1 1 .0 0 0 H A 33 67 67 67 33 67 67 K* 0 0 0 0 33 0 0 H 3 3 134 6 7 2 ,0 0 0 67 3 .0 0 0 1 .0 0 0 GY A 3 3 67 o o H 2,00 0 1 0, 0 00 8 7 .0 0 0 8 0 .0 0 0 4 2 .0 0 0 1 8 .0 0 0 3 ,0 0 0 D ep th 26 9 S 1 m 3 m 5 m 8 m 14 m 2 0 m 2 2 -2 3 m 2 5 -2 6 m 3 0 m ■„ 60 (1966): 4

T

a

b

le

H

I.

M

in

im

u

m

n

u

m

b

er

s

o

f

ae

ro

b

ic

co

lo

n

y

-f

o

rm

in

g

m

ic

ro

o

rg

an

is

m

s

p

er

1 0 0 0m

l

o fw

at

er

.

T h e d a ta ref er to sa m p le s ta k en a t d if fe re n t si te s in th e es tu a ry on fo ur d if fe re n t d a te s, a t v a rio u s v er ti ca l ca st s. T h e n u m b er s are ca lc u la te d fro m co u n ts of fo u r d if fe re n t m ed ia i. e. g lu co se -y ea st agar (G Y A ), “ H a g em ” -m a lt a g ar ( H A ), g lu co se -y ea st m a lt p ep to n agar (W A) a n d m ea t-p ep to n a g a r (M P A ). T o ta l n u m b e r (T ), n u m b e r o f y ea st (Y ). S = S u rf a ce B = B o tt o m . o o o I> o o o o o < Ph o CD o o o o o o 00 ©^ CD to q o' CD o' ©^ ©" q to ©^ to q o to o © to o CM o rH T-H CM k o o o o o o o i> CO o o o o o o o > o O CD oo o o o o o o o o oo o o o o o to o o o o o to o COCO T-H T-H toCD oto oo CM toCO toI> CMto 00o o 05 05 I> to CD _ co r» o >> o o I-" l> o o CD oo CD CD CD CD a '—• CM CO < CO 00 X o o o o CO o o o o o o o o o o CO o ■'■f o o o to to o t-1 O to to o rH to to to l> to 1^- T-H CM co T_| CM CM _ _ 1^ l> CO o 1> o o o TH CO CO CM T-H T-H CM -r '—" s—' N—•" k o CO o o o o o o o o o o O o o CD o o o o o o o o L_, O CO o o o o o o o to 00 o o o o to CO to o CO o to to CO CO o 1-1 to o < o o o o o o o o o Ph o o o o o o o o o o o o 00 Ö o CM o C-H © J-, o CO CD l> CO to o .—1 o CO CO CO CD o o 00 k I> 1il

tO o o o o CO CD o o o o o o o k o o o o CO CO o o o o o o o o o o o CO T-H o o o to o o © o CO to o CM CM CD 00 CD to -C o CO l'' o to CO CM CO CD tn o o o o [> CO o o o Tt< o 05 CM CO X < X oo otO oo oo CD l> oo oo oo too to o o k tO Or © cq © © CD CM Tf cm" cm" 1—1 I" rH o CO o o 17 o o o o o o o o o o o k o o o o o o o O k <3o' q©" ©^00 I> CD q CD q CM CD as" oo 1^-" o oo 1—1 th T-H T-H 1 CO B a to s B to B B to & B B B £ B B 05 CM to CM CM to CM to to © C/3 to to to C/3 CP C/3 CQ C/3 CM C/3 CP C/3 CP C/3 CM 7-1 CM < < <c < 05 o y—4 05 o rH to Ph CD CD I> CD CD CD C/3 CM CM CM CM CM CM Sv. Hot. Tidskr., 60 (1966): 4arbitrary groups may be questioned of course. The special hydro- graphical conditions, however, which characterize this water area may admit of such an arrangement. Concerning water of high salini ties in general, hardly any Atlantic water characterized by a salinity

exceeding 35 %0 S will be found, whereas North Sea water of a salinity of 34 to 35 %0 occurs in the deepest parts of the area and above this layer, mixed water e.g. Norwegian coastal water (30) 32-34 %„ S will be found. These masses of high salinity are layered by water from the Baltic current, with salinities ranging from about 15 to 30 %0 S. Sharp haloclines between these water-masses can be observed (see e.g. Pettersson & Ekman, 1891, Steemann Nielsen, 1940, 1964). Furthermore, layering due to the freshwater supply into the estuary also occurs.

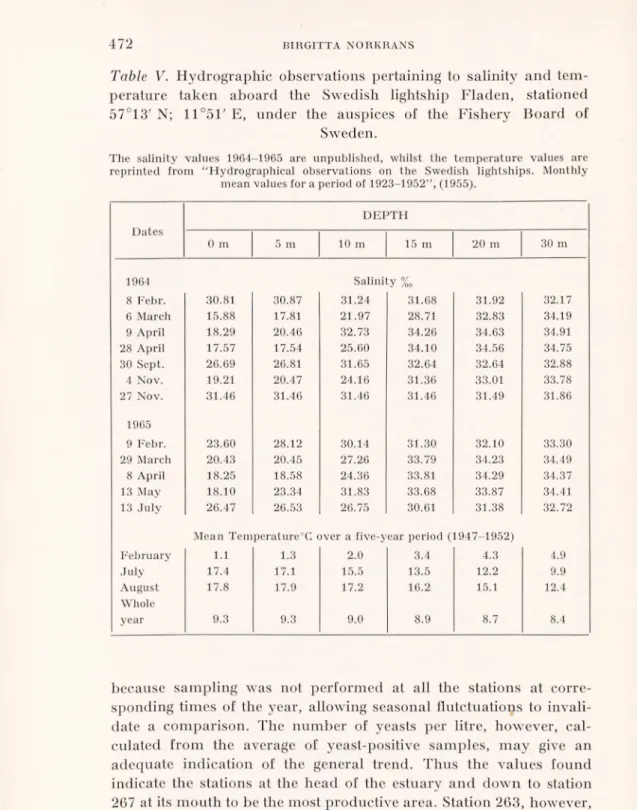

Hydrographical observations are made daily by the Swedish lightships. In Table V, some data for the sampling days are given by the lightship Fladen, positioned at 57°13'N, 11°51' E, from which an approximation for the salinity situation at the outermost sampling stations can be made. At days when a sharp halocline was present, it was found in more than 50 % of the cases between 10 to 20 meters. This might explain the fact that the 14-15 m zone was the one giving the highest percentage of yeast-positive samples, as interphases between watercurrents of different salinities are known to accumu late organic matter (Kiuss 1961).

The low percentage of yeast-positive samples in the group 20-26 m is striking. All the negative samples except one had a salinity value of 34 %0 or higher, and only two samples of the same salinity charac ter were positive. From these layers of North Sea water the smallest average number for yeast cells/litre of positive sample, i.e. 26, was

also calculated (see Table IVa).

Since interphases accumulate organic matter, which, in its turn, governs the growth of heterotrophic microorganisms, not only should more positive samples be found there but also the population density of the microorganisms should be greater there. Though this is not apparent from the average value of yeast cells/lilre in the 14—15 m group, an attractive explanation for the high yeast value of 510 cells/ litre of 4 November 1964 (Table II) might lie in the special conditions resulting from the marked haloclines (Table V) prevailing on this date. The same explanation might also be valid for the high values of 6 March 1964 (Table I), when moreover a conspicuous, dense dia- tomflora was found in the samples (inter alia Talassiosira, Nitzschia

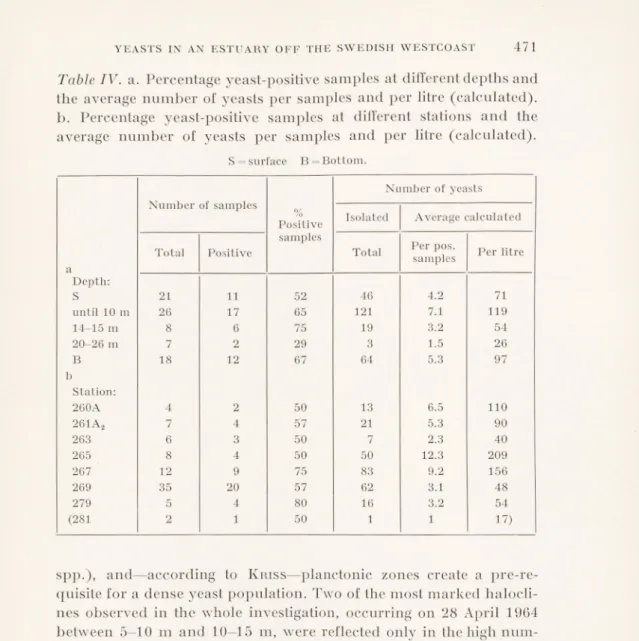

Table IV. a. Percentage yeast-positive samples at different depths and

the average number of yeasts per samples and per litre (calculated), b. Percentage yeast-positive samples at different stations and the average number of yeasts per samples and per litre (calculated).

S= surface B = Bottom.

Number of samples

Number of yeasts

%

Positive Isolated Average calculated

a

Total Positive

samples

Total Per pos. samples Per litre

Depth: S 21 11 52 46 4.2 71 until 10 m 26 17 65 121 7.1 119 14-15 m 8 6 75 19 3.2 54 20-26 m 7 2 29 3 1.5 26 B 18 12 67 64 5.3 97 b Station: 260A 4 2 50 13 6.5 110 261A2 7 4 57 21 5.3 90 263 6 3 50 7 2.3 40 265 8 4 50 50 12.3 209 267 12 9 75 83 9.2 156 269 35 20 57 62 3.1 48 279 5 4 80 16 3.2 54 (281 2 1 50 i 1 17)

spp.), and—according to Kriss—planctonic zones create a pre-re quisite for a dense yeast population. Two of the most marked halocli- nes observed in the whole investigation, occurring on 28 April 1964 between 5-10 m and 10—15 m, were reflected only in the high num bers of the bacterial flora. In the dense population at 8 m and 14 m, a yellow, easily recognized, agar-liquefying bacteria was observed, not present in the 3 m-sample which has just as dense a iloral popula tion; this is another indication for water layering.

Horisontal distribution. Regarding the horizontal distribution, a few remarks would be appropriate. The percentage yeast-positive samples at the different stations were calculated (see Table IV b), but no comparative conclusions between the different sites could be drawn, partly because the observations were too few, and partly

Table V. Hydrographic observations pertaining to salinity and tem

perature taken aboard the Swedish lightship Fladen, stationed 57°13' N; 11°51' E, under the auspices of the Fishery Board of

Sweden.

The salinity values 1964-1965 are unpublished, whilst the temperature values are reprinted from “Hydrographical observations on the Swedish lightships. Monthly

mean values for a period of 1923-1952”, (1955).

Dates DEPTH 0 m 5 m 10 m 15 m 20 m 30 m 1964 Salinity %0 8 Febr. 30.81 CO Ö oo !>■ 31.24 31.68 31.92 32.17 6 March 15.88 17.81 21.97 28.71 32.83 34.19 9 April 18.29 20.46 32.73 34.26 34.63 34.91 28 April 17.57 17.54 25.60 34.10 34.56 34.75 30 Sept. 26.69 26.81 31.65 32.64 32.64 32.88 4 Nov. 19.21 20.47 24.16 31.36 33.01 33.78 27 Nov. 31.46 31.46 31.46 31.46 31.49 31.86 1965 9 Febr. 23.60 28.12 30.14 31.30 32.10 33.30 29 March 20.43 20.45 27.26 33.79 34.23 34.49 8 April 18.25 18.58 24.36 33.81 34.29 34.37 13 May 18.10 23.34 31.83 33.68 33.87 34.41 13 July 26.47 26.53 26.75 30.61 31.38 32.72

Mean Temperature°G over a five-year period (1947-1952)

February 1.1 1.3 2.0 3.4 4.3 4.9

July 17.4 17.1 15.5 13.5 12.2 9.9

August 17.8 17.9 17.2 16.2 15.1 12.4

Whole

year 9.3 9.3 9.0 8.9 8.7 8.4

because sampling was not performed at all the stations at corre sponding times of the year, allowing seasonal flutctuations to invali date a comparison. The number of yeasts per litre, however, cal culated from the average of yeast-positive samples, may give an adequate indication of the general trend. Thus the values found indicate the stations at the head of the estuary and down to station 267 at its mouth to be the most productive area. Station 263, however, formed an exception, coming closer to stations 269, 279 and 281 in

character. Hydrographical data indicated a concentration of high saline water around this station, probably explaining the pheno menon observed (Gustafsson & Olsson, private communication). The great difference in the numbers of microorganisms between samples from the soil-affected shallow head of the estuary and from its mouth can be seen from Table III, where a few samples from the same dates are presented. A heavy bacterial flora dominated by generally soilinhabiting species such as Bacillus mycoides, B. cereus and other Bacillus spp., was found at station 260A on 29 March 1965. The mycoflora too was dense, although few yeasts were present. In the surface samples, all the organisms obtained on HA were myce lium-forming fungi, common soil-inhabitants such as Penicillium,

Aspergillus, Fusarium and Trichoderma spp., and none of the genus

often represented here in other samples such as e.g. Cephalosporium spp., was observed. This sample was indeed singularly soil-infected: it was so turbid as to offer exceptional difficulties to filtration; the spring drainage by the river Kungsbackaån had been going on for some time; a pressing wind kept the river water back in the head of the estuary, giving the sample quite a fresh-water character, the salinity being just 0.5 %„ (personal communication, L. Gustafsson). The 261A2 samples are similar, though less extreme. The 279 samples showed quite another character. The bacterial number was compara- lively small, the soil influence was not stressed, but the yeast number, on the other hand, was about the same as in the previously mentioned samples. Strains of Crytococcous albidus and Debaryomyces hansenii were found in the bottom sample, where the salinity was 34.9 %„ in dicating North Sea water. Ten days later, however, the situation was somewhat changed, mainly with regard to the surface samples of 279, where an increase in the bacterial number was pronounced.

Bacillus mycoides was found which, combined with a decrease in

salinity, might suggest a dilution by the river drainage along the surface. During this study, the usefulness of B. mycoides as an indica tor for soil influence occurred to the author. It is common in soil, easily detected, fast growing and not fastidious.

Yeast constituent of the total heterothrophic microorganism flora. The highest Ymax found was 510 (Table II, 4 Nov.) which is thirty times larger than the lowest one (17), whereas the highest Imax value of 3 x 106 (Table III, 29 March) exceeded the lowest one, 167, (the locus) about 17,000 times. When all the samples for which

So. Bot. Tidskr., 60 (1966): i

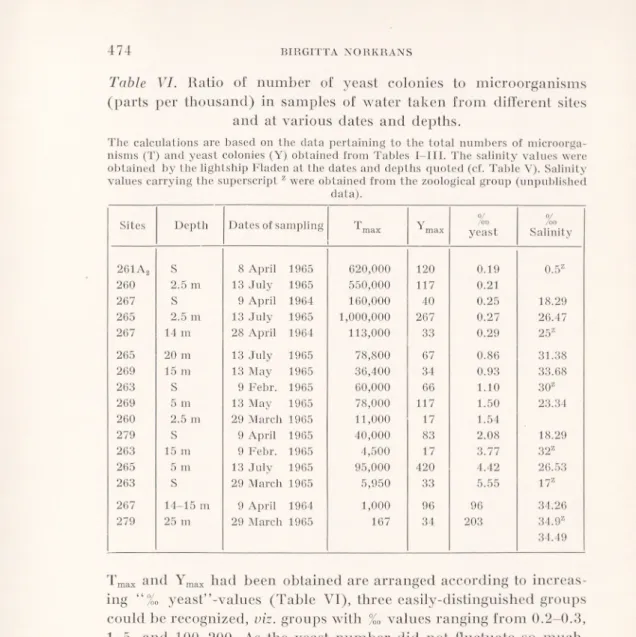

Table VI. Ratio of number of yeast colonies to microorganisms

(parts per thousand) in samples of water taken from different sites and at various dates and depths.

The calculations are based on the data pertaining to the total numbers of microorga nisms (T) and yeast colonies (Y) obtained from Tables I—III. The salinity values were obtained by the lightship Fladen at the dates and depths quoted (cf. Table V). Salinity values carrying the superscript z were obtained from the zoological group (unpublished

data).

Sites Depth Dates of sampling ^ max Y max 0/ /oo yeast °/ /OO Salinity 261A2 S 8 April 1965 620,000 120 0.19 0.5Z 260 2.5 m 13 July 1965 550,000 117 0.21 267 S 9 April 1964 160,000 40 0.25 18.29 265 2.5 m 13 July 1965 1,000,000 267 0.27 26.47 267 14 m 28 April 1964 113,000 33 0.29 25z 265 20 m 13 July 1965 78,800 67 0.86 31.38 269 15 m 13 May 1965 36,400 34 0.93 33.68 263 S 9 Febr. 1965 60,000 66 1.10 30z 269 5 m 13 May 1965 78,000 117 1.50 23.34 260 2.5 m 29 March 1965 11,000 17 1.54 279 S 9 April 1965 40,000 83 2.08 18.29 263 15 m 9 Febr. 1965 4,500 17 3.77 32z 265 5 m 13 July 1965 95,000 420 4.42 26.53 263 s 29 March 1965 5,950 33 5.55 17z 267 14-15 m 9 April 1964 1,000 96 96 34,26 279 25 m 29 March 1965 167 34 203 34.9Z 34.49

Tmax and Ymax had been obtained are arranged according to increas ing yeasf’-values (Table VI), three easily-distinguished groups could be recognized, viz. groups with %0 values ranging from 0.2—0.3, 1-5, and 100—200. As the yeast number did not fluctuate so much, the Tmax value—approximating to the total bacterial number—practi cally governed the classification. Thus, all values >100,000 will be found in the first group, whilst samples of < 1000 will be found in the third. As the production of heterotrophic microorganisms is a function of organic matter available, very small amounts of organic substances will be present in samples of the third group, an assump tion which seems reasonable in view of the salinity values indicating unmixed North Sea water. Because detailed hydrographical and nutrient data for the samples of the more complex group two are lacking, it will not be discussed until such are available. In group

one, the high Tmax values indicate an increased supply of organic material, involving supply of cells as well as assimilable matter. This may be due to run-off from the land (261Aa, 260A, 267S), re flected in low salinities and terrestrial flora, accumulation in inter phases between the different water masses (267, 14 m) and, pollu tion, presumably occurring during summer, at station 265 in this otherwise only slightly polluted area. Certainly, Ihe increase in the watertemperature (cf. Table V) during summer also favour the growth of microorganisms present, ft is striking that a corresponding increase in the number of yeasts did not occurr. A failing supply of yeast cells seems not to be a probable reason, three other reasons, however, could be considered. Firstly, the yeast cells are brought into the sea water, by e.g. land drainage, pollution, animals, and from plants which are known to harbour yeasts. They can remain viable for a time in the sea water, although they are not able to reproduce. In at least three samples of this material, however, rela tively high numbers—510, 367 and 133/litre—of apparently homo genous populations of Rhodotorula spp. and of Cryptococcus albidus have been obtained, which might indicate a certain reproduction. Secondly if the generation time of yeasts in sea water is long in comparison with that for bacteria, they will lose in the keen competi tion for the organic source before any considerable yeast reproduc tion will have occurred. Finally, the low yeast value may depend upon anti-yeast activity from bacterial or other sources, found and discussed by Buck & Meyers (1965).

A range of 17-510 yeast cells/litre corresponds fairly well with some other determinations of yeast concentration in the sea. From an investigation from the Scripps Institution, La Jolla, California (Uden & Castelo-Branco, 1963) on sub-surface samples, a range of 10-230 yeast cells per litre can be calculated if the numbers of

Metschnikowia spp. are subtracted—which might very well be done,

since these species have not been found in the present water area; two samples, where the high numbers of 1920 and 3670 are caused entirely by Rhodotorula glutinis, are excluded. Exclusion of the pure

Rhodotorula samples in the present study resulted in a yeast number

range of 17-267. From a study of two temperate estuaries oil Portugal and the adjacent Atlantic Ocean (Taysi & Uden, 1964), average values ranging from 95-375 yeast cells per litre were reported, except for the most polluted area, which had a value of 1228. The corresponding range for average values here will be 9-119 yeast cells per litre.

0) 75 £ <D Fh O) te 3 ^ o ^ (-. £ 33 rrH .S.S OS 05 o

HI

•sz w ni ft* a <vft

-Q C 3 ; er >-« C/5 . o -Q o il c PQ o» . . ■ X3 C' c, _ca 5 ^ E 3 3 Ohtj 3 _3 05 „. _ fl c. C/5 r1-! 4_ S ^ -0D3 C 33 3 .£ Cl. £ c 5 3 >5 a 33 3 Oß T3 05 .2 *3 CS .£ 33 C/5 3 2 33 O CO S-. > K^'ö ?*> 05 .13 .3 .2 *3 13 „Q 3ß a. c ‘C CD 05 ff K*> eo 4 ^3 CO (M CO o 3. „ . c

^33T—

( iO CD T-« uO 00 CS 00 CD rf r*» CD CDT-, ,_,

oo T-H y-l CO CO <M CO 03 ,q O £ H g CD 05 „ CD io co co o X x &0 05 1 I 1 w ö" O £ 3 H « w W 05 05 < U Z o 3 * g 8 z < CS .• < —. c —. o. a 6. = " S P O _) o 3 W Z Z 2 oo •< C/3 2 2 oo oo X X w z z :~ 2 C czj S2 3 ^ ^ 3 X Sv. Bot. Tidskr., 60 (1966): 4CD Tf Dl Ol CO M co r* oo 1—< CO r-i CD CD CO I I I © ^ ^ Tt - CO CO lO I £ CO CO X CO lO I CO X IM s i Tf Tf T|< CO CO CO I I I C O ö g ■g g 5 j o> « E 35 a ~ o _ 3*5; t, ^ c. « .P r/C Cl P C/3 •§ w -S -§ rfS a; w ft; & g c Ö £ c o rn S % t -. £ £ «o O-i 1 s 2 •S 3 — K z P, C/3 ft, ft, c fa oo uo 5 X to Sv. Hot. Tidskr., 60 (1966): i

The aforementioned data have been given without pretentions to dissolve the problem of the distribution of yeast constituents just only in order to point to some factors of the very complex pattern governing the distribution, factors such as: water currents and waterlayering, tide, wind and watertemperature, accumulation in interphases, the primary production in sea, land drainage, soil influence, pollution, all in its turn influenced by seasonal fluctuations.

Yeasts identified. From the 48 yeast-positive samples, 253 single colony yeasts have been isolated. Fourty nine have been identified and classified into genus and species. Since the interest was con centrated on “marine” yeasts, all were selected from the outermost stations, except one. As can be seen from Table VII, the genera

Rhodotorula and Cryptococcus formed about half of the material

identified, thus occupying a dominating position together with

Debaryomyces hansenii, (according to van Rij, 1964, including I),

hansenü (Zopf) Lodder et van Rij, D. kloeckeri Guillermond et Péju, D. siibglobosus (Zach) Lodder et van Rij and I), nicotiance

Giovannozzi). If Debaryomyces hansenii and its imperfect form,

Torulopsis famata are combined, they constitute about a fourth of

the identified species. The remaining fourth consists of strains of

Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the Candida parapsilosis group (Phaff & do Carmo-Sousa, 1962) and one strain each of C. zeylanoides, C. sp. Pichia etcliellsii and P. fluxuum incidentally present. As only a part

of the material has been identified, it would seem unwise to declare that this is the definite composition of the yeast flora in the outermost part of the area. Judging from the morphology of the other isolated strains, however, it would be probable that the three dominating genera would distribute themselves in a similar manner even in the remaining material. With regard to the group containing the Saccharo

myces and the Candida parapsilosis, it is quite possible that the compo

sition of this group would be different, and some other incidental species would occupy it.

The occurrence of Rhodotorula, Cryptococcus spp. and Debaryo-

myces hansenii among the species identified in the present water

area is not surprising. Rhodotorula and Cryptococcus spp. seem to be ubiquitous in sea water. They have been reported from all the in vestigated areas previously mentioned and predominate in open sea water as well as in the coastal zone off southern California (Uden &

Castel-Branco, 1963), where they occur together with Metschnikowia

zobellii and M. krissii. These latter two do not seem to be present here,

and indeed, neither is it to be expected if they are preferentially harboured by kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera, Uden & Castelo Branco, 1963). Besides Rhodotorula, Debaryomyces spp. are reported as predo minants in Portugeese estuaries and in the adjacent Atlantic Ocean (Taysi & Uden, 1964). Furthermore, Debaryomyces hansenii, if used according to v. Ru as here, constituted more than 10 per cent of the species isolated off the Indian coast by Bhat & Kachwalla (1955). Candida parapsilosis too is widespread in oceans, predominating in

the estuaries of Florida, in the Bay of Biscay, and open ocean water (Fell et al. 1960, 1963). On the other hand, Candida spp. such as

C. albicans, C. tropicalis and C. krusei, widespread in polluted areas, have not been found here and could not have been more than incidentally present. Saccharomyces cerevisiae was mentioned from this water area already by Fischer (1894).

The striking ubiquitous occurrence of some yeasts in ocean waters and in other water bodies containing ocean water is easily under standable. Except for the atmosphere, no environment has condi tions as favourable for global uniformity as the big water masses. Judging from the salinity values (Table VII), the predominant marine flora may even here originate from ocean water — Cryptococcus

albidus as well as Debaryomyces hansenii have been isolated from

water samples of salinity of 34.9 %0 S—from where a distribution into the estuaries may take place. At the same time, of course, yeasts are being steadily deposited into the water by, among other sources, land drainage. From these yeasts a selection takes place. This selec tion may depend either on a higher ability on the part of some species to survive in sea water or on their capacity to reproduce in it. In the linal phase, these different species may be gathered into a common oceanic stock. Regarding investigations on soil-occurring yeasts in Swedish soils, the author knows of only one such work, by Capriotti

(1959). Since soil does not comprise an environment of the above- mentioned uniformity, surely an uneven distribution does occurr in soils. Of the existing Swedish soil-yeasts, given by Capriotti, how ever, only Candida parapsilosis and Rhodotorula rubra were found in our water material, and the outstanding predominant mentioned by him for Swedish soils, viz. Debaryomyces castellii, was not found in the waters investigated. On the other hand, Cryptococcus albidus, found in our water areas, was not present in the Swedish soils studied, although very common in Spanish soils according to Capriotti, and

Sv. Bot. Tidskr., 60 (1966): 4 31 - 663875

representing as much as one quarter of all the species isolated from Australian soils (di Menna, 1955). These facts, beside the high salinities referred to above, indicate that yeasts found in the outer most part of the area investigated may derive from a common oceanic “pool” as well as from inshore sources.

Summary.

The occurrence of yeasts in eighty water samples from eight sta tions situated along “Kungsbackafjorden”, an estuary at the Swedish west-coast, and in the adjacent sea area, has been studied. Forty eight samples, i.e. 60 per cent, were yeast-positive, containing a minimum of 17—510 viable yeast cells per litre; 253 single-colony isolates have been made, of which one fifth have been classified into genus and species. Since the interest was concentrated on “marine” yeasts, all were selected from the outermost stations, except one.

Cryptococcus and Rhodotorula species form about half of the identi

fied material, thus dominating together with Debaryomyces hansenii. They have been isolated from water samples of salinities higher than 34 %0, corresponding to North Sea water, as well as from samples of considerably lower salinity. The fraction of the total heterotrophic microorganism flora formed by the yeasts has been estimated and the causes of this quantitative relationship is discussed.

Acknowledgements.

During a visit at the yeast division, Centralbureau voor Schimmelcul- tures, Delft, Holland, in the autumn of 1965, the author had the opportunity to run confirmatory tests for the preliminarily-identified material. Thanks are due to the director, Prof. T. O. Wirén, for providing this extremely valuable privilege and to Dr Slooff and her staff for valuable discussions and help.

This investigation has been supported by grants from Naturresurs kommittén of the Swedish Natural Science Research Council and from the Åke Wibergs Stiftelse, for which grateful acknowledgements are made. The author also wishes to thank miss Ingrid Hjelmgrenfor skilful techni cal assistance.

REFERENCES.

Bhat, J. V. & Kachwalla, N., 1955: Marine Yeasts off the Indian Coast. Proc. Indian Acad. Sei., 41: 9-15.

Buck, J. D. & Meyers, S. P., 1965: Antiyeast activity in the marine envi-

ronment. 1. Ecological considerations.—Limnol. Oceanog. 10:385-391.

Cameron, W. M. & Pritchard, D. W., 1963: Estuaries. - In The Sea,

vol. II. Edited by M. N. Hill, Interscience Publishers, New York, London.

Capriotti, A., 1959: The yeasts of certain soils from Sweden. — Kungl.

Lantbrukshögskolans annaler 25: 185-220.

—»—, 1962: Yeasts of the Miami, Florida, Area III. From sea water, marine animals and decaying materials. — Arch. f. Mikrobiol. 42: 407-414.

Fell, J. \V., Ahearn, D. G., Meyers, S. P. & Roth, F. J., 1960: Isolation of yeasts from Biscayne Bay, Florida and adjacent benthic areas. — Limnol. Oceanog. 5: 366-371.

Fell, J. W. & van Uden, N., 1963: Yeasts in marine Environments. — In Symposium on marine microbiology. Ed. C. H. Oppenheimer.

Charles C. Thomas Publisher. Springfield.

Fischer, B., 1894: Die Bakterien des Meeres. Erg. der Plankton-Expedi

tion der Humboldt-Stiftung IV: g pp. 82. — Kiel und Leipzig.

Gunkel, \V., Jones, G. E. & Zobell, Cl. E., 1961: Influence of volume of nutrient agar medium on development of colonies of marine bacteria. — Helgoländer Wiss. Meeresuntersuchungen 8: 85-93.

Johnson, T. W. & Sparrow, F. K., 1961: Fungi in oceans and estuaries.

— J. Cramer, Weinheim, Germany, 668 pp.

Kreger-Van Rij, N. J. W., 1964: A taxonomic study of the yeast genera

Endomycopsis, Pichia and Debaryomyces. Diss. — Leiden.

Kriss, A. E., 1961: Meeres-Mikrobiologie. — Jena.

Lodder, J. & Kreger -Van Rij, N. J. W., 1952: The yeasts A taxonomic study. — Amsterdam.

Menna, M. E. di, 1955: A search for pathogenic species of yeasts in New Zealand soils. — J. gen. Microbiol. 12: 54-62.

Pettersson, O. & Ekman, G., 1891: Grunddragen av Skageracks och Katte gatts Hydrografi. — Kongl. Svenska Vetensk.-Akad. Handl. Bd. 24, No. 11. 1-62.

I’iiaff, H. J. & do Carmo-Sousa, L., 1962: Four new species of yeast isolated from insect frass in bark of Tsuga heterophylla (Raf.) Sargent. - Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. J. Microbiol., Serol. 28: 193-207.

Siepmann, R. & Hönk, W., 1962: Ueber Hefen und einige Pilze (Fungi imp., Hyphales) aus dem Nordatlantik. — Veröffentl. Inst. Meeresforsch. Bremerhaven 8: 79-98.

Sierra, Gonzalo, 1957: A simple method for the detection of lipolytic

activity of micro-organisms and some observations on the influence of the contact between cells and fatty substrates. — Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. J. Microbiol., Serol. 23: 15-22.

Steemann Nielsen, E., 1940: Die Produktionsbedingungen des Phyto

planktons im Obergangsgebiet zwischen der Nord- und Ostsee. Medd. fra Komissionen for Danmarks F’iskeri og Havundersokelser. Serie: Plankton: Bd III. Nr 4. 1-55.

Steemann Nielsen, E., 1964: Investigations of the rate of primary produc tion at two Danish light ships in the transition area between the North Sea and the Baltic. — Medd. fra Danmarks Fiskeri och Havundersogelser, NS 4: 31 -77.

Taysi, I. & Uden, N. van., 1964: Occurrence and population densities of yeast species in an estuarine—marine area. — Limnol. Oceanog. 9: 42-45.

Uden, N. van & Castelo-Branco, R., 1963: Yeast species in pacific water, air, animals and kelp off Southern California. — Limnol. Oceanog. 8: 323-329.

Uden, N. van & Zobell, C. E., 1962: Candida marina nov. spec. Torulopsis torresii nov. spec, and T. Maris nov. spec., three yeasts from the Torres Strait. — Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, J. Microbiol. Serol., 28: 275-283.

Wickerham, L. J., 1951: Taxonomy of yeasts. — U.S. Dept. Agr. Tech.

Bull. No. 1029, pp. 1-55.

Zobell, C. E., 1946: Marine microbiology. — Chronica Botanica. Co.,

Waltham, Mass.

Monthly average values of hydrographical observations on Swedish light ships 1923-1952. Fishery Board of Sweden, Series Hydrography, Report No. 5.

Hydrographical observations on Swedish lightships in 1964, 1965. Fishery Board of Sweden. Series Hydrography, Report No:s 18, 19 (un published).

Jägerskiöld, A. L. Station map, Special C. (Unpublished) — Natural

History Museum, Göteborg.

NOTES ON SOME CONVOLVULACEAE

FROM BRAZIL.

BY

KARL AFZELIUS. Museum of Natural History, Stockholm.

In a collection of Conuolvulaceae from Brazil are three species which seem to be undescribed and the descriptions are given below. Some specimens of Ipomoea seem to be intermediate between I.

saopaolista O’Donell and I. reticulata O’Donell and the species

are discussed.

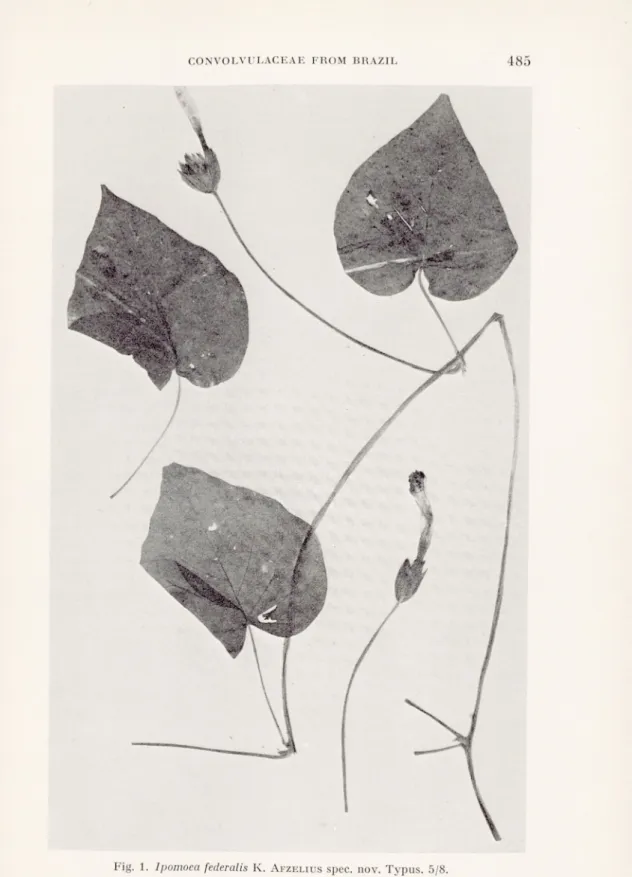

Ipomoea federalis K. AfzeLIUS nov. spec.

Yolubilis. Caules pilis hispidis retrorsis c. 2 mm longis flavido-albidis tecti. Internodia c. 20 cm longa. Folia longe pedunculata. Petioli usque ad 7 cm longi, retrorso-pilosi. Laminae late cordatae, acuminatae, usque ad 10 cm longae, 11 cm latae, utrinque pilis hispidis longis adpressis sparsis tectae, margine integrae, basi cordato, sinu angusto.

Cymae capituliformes, pauciflorae, flores circiter 4. Pedunculi longi, 12-24 cm, retrorso-hispidi. Bracteae 2 exteriores cymam circumdantes, ovatae, longe acuminatae, 20-25 mm longae, 10-12 mm latae, externe pilis antrorsis sparsis, in margine crebris tectae, interne glabrae. Bracteae interiores et bracteolae usque ad 10 mm longae, 3 mm latae, pilositas ut in bracteis exterioribus.

Flores breviter pedicellatae. Sepala extus et in margine pilosa, intus glabra, exteriora ovato-lanceolata, 15-19 mm longa, 4-7 mm lata, interiora anguste lanceolata, 13-15 mm longa, 2 mm lata. Corolla verisimiliterinfundi- buliformis (marcida), usque ad 6 cm longa, in parte inferiore et in areis mesopetalis sparse pilosa, alba, superne violacea. Filamenta in parte infe riore glanduloso-pilosa. Pollen spinosum. Stigma trilobatum. Discus annula ris.

Typus. Brasilia, Brasilia D. F. Cörrego Maranhao, J. M. Pires, N. T.

Silva, R. Souza 9487, 2.III. 1961. Paratypus. Brasilia D. F., Fercal, E. P.

Heringer8178/372, 5.IV. 1961.

I. Piresii affinis. Differt internodiis et petiolis longioribus, foliorum

laminis majoribus, late cordatis, non lobatis, pedunculis longioribus, brac teis longioribus et latioribus, sepalis longioribus et angustioribus, corollis longioribus.

Climbing. Stems with stiff, downward directed, yellowish-white, c. 2 mm long hairs. Internodes c. 20 cm long. Leaves broadly cordate, acuminate, up to 10 cm long and 11 cm broad, cordate at the base, margins entire or slightly undulated, with long, stiff, appressed, sparse hairs on both sides. Petioles up to 7 (in one case 19) cm long with hairiness as on the stem.

Cymes capitate, few-flowered, probably as a rule with 4 flowers. Peduncles 12—24 cm long with hairiness as on the stem. Two big outer bracts enclosing the cyme, ovate, long acuminate, 20-25 mm long, 10—12 mm broad, with scattered hairs on the outside, densely hairy On the margins and glabrous inside. Inner bracts and bracteoles up to 10 mm long and 3 mm broad with hairiness as on the outer bracts. Flowers with short pedicels, up to 2 mm. Sepals pilose on the outside and the margins, glabrous on the inside, the outer ones ovate-lanceolate, 15—19 mm long, 4—7 mm broad, the inner ones narrowly lanceolate, 13—15 mm long, 2 mm broad. Corolla (withered) probably funnel-shaped, up to 6 cm long, hairy on Ihe mesopetal fields, white with the upper parts lilac. Filaments glandular-hairy at the base. Pollen spiny. Stigma three-lobate. Discus low, annular.

This species is closely related to Ipomoea Piresii O’Donell and has a similar inflorescence. It differs by having longer internodes, longer petioles, larger leaf-blades of different shape, broadly cor date, not three-lobate, longer peduncles, larger bracts, the two outer most enclosing the cyme and larger corolla of different colour.

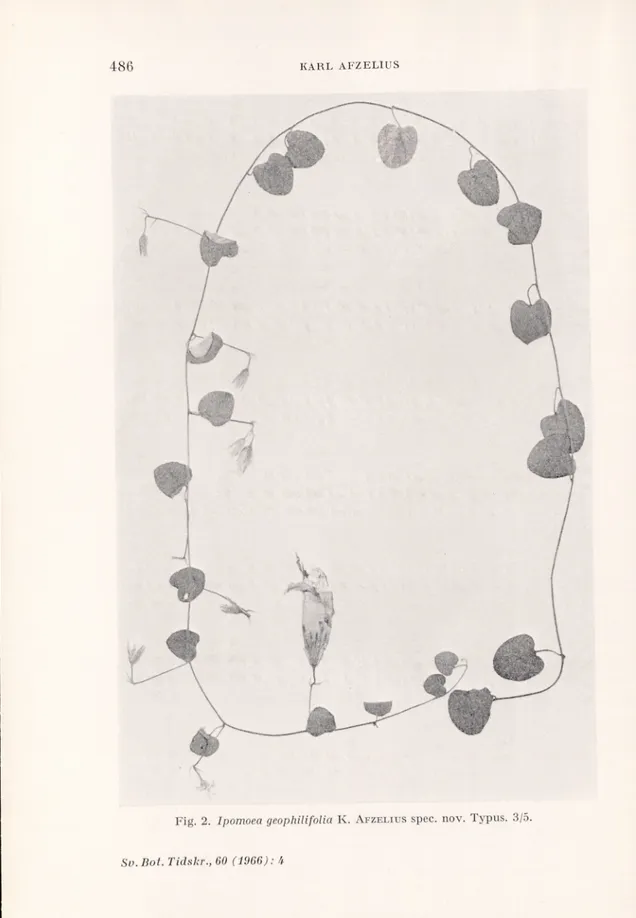

Ipomoea geophilifolia K. Afzelius spec. nov.

Herbacea, procumbens seu volubilis. Caules cylindrici, tenues, 1 mm diam., pilis subfulvis usque ad 2 mm longis tecti. Internodia 4-6 cm longa. Folia petiolata, late cordata. Petioli c. 15 mm longi, dense pilosi. Laminae apice rotundatae, mucronulatae, basi aperte cordatae, usque ad 23 mm longae et latae, supra pilis subfulvis sparsis adpressis, subtus pilis argenteis adpressis dense tectae. Inflorescentiae uniflorae vet biflorae, in axillis foliorum. Pedunculi 25-35 mm longi, pilosi. Bracteae 2-3, lanceolato-subula- tae, pilosae, 6-8 mm longae. Pedicelli c. 10 mm longi, pilosi.

Sepala lanceolata, acuta, dense pilosa, c. 12-13 mm longa, c. 3 mm lata. Corolla campanulata, 5-6 cm longa, rosea seu alba, in parte inferiore laxe, in areis mesopetalis dense adpresse pilosa. Filamenta brevia, lata, in parte inferiore glanduloso-pilosa. Pollen spinosum. Stigma biglobosum. Discus annularis,

Typus. Brasilia, Brasilia D. F., Cabeca do Yeado, E. P. Heringer 8029/ 220, 2.III. 1961, flores rosei. Paratypus. Heringer 8030/221, eodem loco

2.III. 1961, flores albi.

..

,4 .■

..S' •.

111 ill

Fig. 2. Ipomoea geophUifolia K. Afzelius spec. nov. Typus. 3/5.

Herbaceous, procumbent, perhaps climbing. Stems 1 mm thick, with long tawny hairs. Leaves with about 15 mm long, densely hairy petioles and broadly cordate blades, about 23 mm long and broad, mucronulate, with rather sparse, loosely appressed tawny hairs on the upper side and dense, appressed, white, silky hairiness under neath. About five pairs of primary lateral nerves, very prominent on the under side. Inflorescences uniflorous or biflorous. Peduncles 25-35 mm long, hairy, bracts linear-lanceolate, pilose, 6-8 mm long, pedicels about 10 mm long, pilose. Sepals lanceolate, densely and appressed silky hairy on the outside. Corolla campanulate, pink or white.

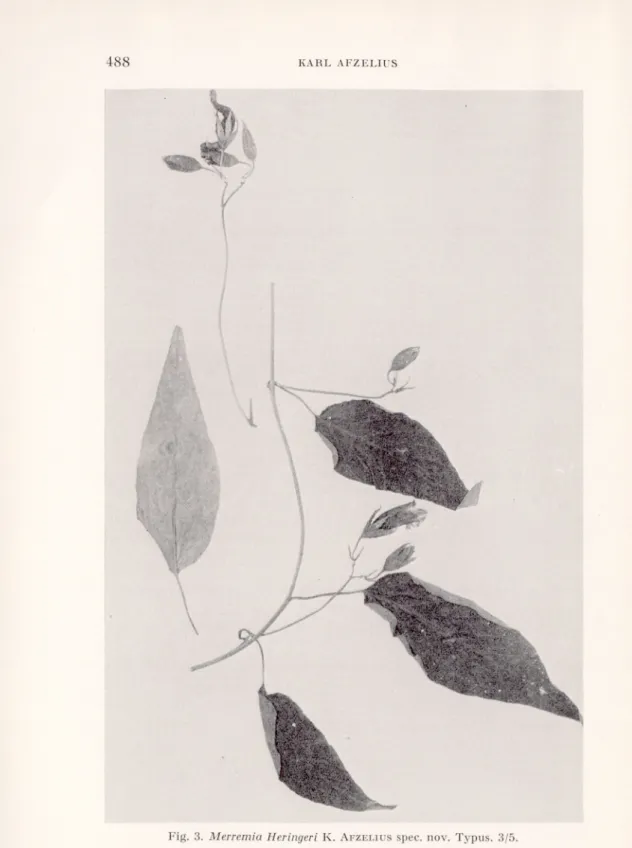

Merremia Heringeri K. AfzELIUS spec. nov.

Volubilis. Caules cylindrici, 2 mm diam., pubescentes. Internodia c. 5-9 cm longa. Petioli 1,5-2,5 cm longi, dense pubescentes. Laminae ovato- lanceolatae, acuminatae, basi rotundatae, supra laxe, subtus densior pub escentes, usque ad 11 cm longae, 3,5 cm latae. Cymae pauciflorae. Pedunculi 3-10 cm longi, pubescentes. Bracteae anguste lanceolatae, c. 7 mm longae, supra glabrae, subtus adpresse pubescentes, caducae. Pedicelli c. 1 cm longi, pubescentes. Sepala lanceolata, acuta, extus pilis luteolis adpressis tecta, intus glabra, 15-16 mm longa, 3-3,5 mm lata. Corolla campanulata, alba, 2,5-3 cm longa, in areis mesopetalis longe pilosa. Filamenta usque ad 14 mm longa, parte inferiore glanduloso-pilosa. Pollen plicatum. Stigma biglobosum. Discus annularis.

Typus. Heringer 5166, Brasilia, Minas Gerais, Horto Florestal de Paraopeba, 8.V. 1956. Paratypus. Heringer 3890, eodem loco, 2.VI. 1955.

Stem herbaceous, twining, about 2 mm in diameter, with rather soft, more or less appressed, yellowish hairs. Internodes 5—9 mm long. Leaves with 1.5-2.5 long, pubescent petioles and ovato-lanceo- late leaf-blades with entire margins, up to 11 cm long and 3.5 cm broad. In dry state the upper surface dark brownish green and with sparse appressed brownish hairs, the lower surface paler and more densely hairy. The middle vein and the 7—8 pairs of lateral veins prominent. Inflorescences dichasial, lax and few-flowered. Pedun- cules 3-10 cm long, pubescent with soft yellowish hairs. Bracts about 7 mm long, narrowly lanceolate, glabrous on the upper surface, appressed hairy on the lower surface, deciduous. Pedicels about 1 cm long, with short appressed and long spreading yellow hairs. Flowerbuds acute. Sepals all alike, lanceolate with long appressed at the base partly spreading yellow hairs on the outer side, glabrous

K

Fig. 3. Merremia Heringeri K. Afzeliusspec. nov. Typus. 3/5. Sv. Bot. Tidskr., 60 (1966): 4

on the inner. Corolla campanulate, 2.5-3 cm long, white, the meso- petal fields with long, stiff hairs. Filaments hairy at the base. Ovary glabrous. Discus annular. Capsule and seeds not seen.

Ipomoea saopaolista O’DONELL and I. reticulata O DONELL.

Three specimens of Ipomoea from Brazil, Brasilia D. F., Heringer

8015/206, 8193/387 and 8317/511, are nearly related to I. reticulata and I. saopaolista and are a connecting link between them. The difference between these two species is, according to O’Donell in

Lilloa 26 (1953), pp. 389-392, that I. saopaolista has hairy leaves, seldom glabrous beneath, inflorescences with the branches concen trated to the top of the main axis, the sepals a little concave and up to 9 mm long and the corolla 3.5-5 cm long, whereas I. reticulata has glabrous or slightly hairy leaves, inflorescences with the branches scattered along the main axis, the sepals plane and up to 7 mm long and the corolla 2.5-3.5 cm long.

As to the leaves they are sometimes quite alike in the two species and it is impossible to fix a boundary between them. The shape of the inflorescence varies in both species and is undoubtedly a character depending on the environmental conditions. Although the flowers of

I. saopaolista as a rule are bigger than those of I. reticulata the

biggest flowers of I. reticulata are quite as big as the smallest of I.

saopaolista, and the difference in size lies within the genetic variation

limits which we must expect in a species-complex with such an extensive area, and it is hardly possible to consider this difference as a species-distinguishing character. O’Donell discusses the areas

in which the two species occur and points out that I. reticulata hitherto has only been found in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, whereas I. saopaolista is an inhabitant of Brazil, in the states of Minas Gerais, Bio de Janeiro, Såo Paolo and Santa Catharina, and in Paraguay. He mentions that he has seen some Brazilian specimens which he presumes to belong to I. saopaolista but which very much resemble I. reticulata. The new localities in Brasilia D. F. connect the areas of the two species. It seems to me that the two species are forms of a rather variable species within an extensive area and should be united under the name of I. saopaolista O’Donell.

RECENSIONER.

Printz, H., Die Chaetophoralen der Binnengewässer. Eine

systematische Übersicht. — Verlag Dr. W. Junk. Den Haag 1964.

Ramanathan, K. R., Ulotrichales. — Indian Council of Agricultural

Research, Monographs on Algae. New Delhi 1964.

Kürzlich und fast gleichzeitig sind zwei monographische Bearbeitungen der fädigen Grünalgen nämlich der Ulothrichalen-Chaetophoralen Reiben erschienen, die eine schon längst und vielfach empfundene Lücke in der Fachliteratur ausfüllen. Um so mehr erfreulich ist es, dass beide Abhand lungen einander in mancher Hinsicht ergänzen, so dass man dadurch eine mehr zusammenfassende Darstellung des gegenwärtigen Standes der Kenntnisse hierüber erhält. Seit dem Erscheinen der sehr verdienstvollen, vielverwendeten Ulothrichalen-Bearbeitung von Heering in der Süss wasserflora (1914), die nun schon vergriffen und natürlich auch ziemlich veraltet, vor allem aber ergänzungsbedürftig ist, fehlte eigentlich bis in die letzte Zeit ein geeignetes modernes Hand- und Hilfsbuch beim Studium und bei der Bestimmung der Algen dieser, nach allem zu urteilen immerhin noch in reger Formenentwicklung befindlichen Chlorophyceengruppe. Letzterer Umstand äussert sich besonders auch in der oft noch recht un scharfen Abgrenzung der einzelnen Gattungen und anderer Taxa innerhalb der Ulothrichalen und in benachbarten Reihen.

Die Abhandlung Printzsüber die Chaetophoralen des Süsswassers, vom Verfasser selbst bescheiden nur als eine systematische Übersicht bezeich net, ist eine ergänzte Neubearbeitung eines 15 Jahre in Prag verschollenen und nun zutage gekommenen Manuskriptes für die seinerzeit vorgesehene 2. Auflage des Heftes VI von PaschersSüsswasserflora. Da diese bekannte und hochgeschätzte Serie nach dem letzten Weltkrieg leider nicht weiter geführt wurde, ist die vorbereitete Monographie von Printz nun, man möchte sagen zu ihrem Vorteil, separat erschienen. Dies vor allem darum, weil durch das gewählte grössere (als in den Heftchen der Süsswasserflora) Format, die vielen, guten erläuternden Zeichnungen vollständiger, reich licher und in einem nicht zu kleinen Masstab reproduziert werden konnten. Die systematische Einteilung des Stoffes in der Monographie ist freilich etwa dieselbe wie in des Verfassers Bearbeitung dieser Algen in Engler-

Prantls Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien (1927) geblieben. Die Chaeto

phoralen werden demnach auch in dem vorliegenden Buch in erweitertem Sinn erfasst, also einschliesslich der Ulothrichalen, Ulvalen, Chaetophora len, Prasiolalen und Oedogonialen (die letzteren werden dabei aus prak tischen Gründen zwar nicht mitberücksichtigt) in engerem Sinn, von den

Microsporalen nicht zu reden. Es handelt sich hier sicher um einen grösseren, verwandtschaftlich zusammenhängenden Cohors, der sich aber phylo genetisch offensichtlich schon in mehreren kleineren, selbständigen Ent wicklungsreihen oder -richtungen aufgeteilt und sogar weitgehend diffe renziert hat. Diese phyletischen Verzweigungen werden in der Monographie allerdings nur als besondere Familien aufgefasst. Wie so oft auch in anderen ähnlichen Fällen, ist die taxonomische Beurteilung der systematischen Kategorien hier demnach unzweideutig recht subjektiv, was jedoch den eigentlichen Wert des Werkes kaum irgendwie herabzusetzen vermag, da dieser sich vorzüglich in der klaren, sachlichen allgemeinen Übersicht der wichtigsten zytologischen und entwicklungsgeschichtlichen Tatsachen, den konzisen und dennoch prägnanten Beschreibungen und Charakterisierungen der zur Zeit bekannten Süsswassergattungen und -arten der berücksich tigten Gruppe, sowie ebenfalls in der reichen und guten Bebilderung des Werkes liegt, die in der Regel den oft schwer zugänglichen Originalarbei ten entstammt. Auch die Bestimmungsschlüssel machen einen sorgfältig durchdachten und ausgewogenen Eindruck, was die praktische Arbeit mit ihnen weitgehend erleichtern wird und zu den Vorteilen dieses ge schätzten Buches in nennenswerter Weise beiträgt.

Ein paar Anmerkungen systematischen Charakters scheinen mir den noch am Platz. Erstens was die Gattung Binuclearia betrifft. Als die Typus art dieser von Wittrock 1886 aufgestellten Gattung galt bis zum Jahre 1937 die B. tatrana desselben Verfassers. Es handelt sich dabei um eine weitverbreitete, kaltwasserliebende Fadenalge vor allem der Torfseen und ähnlicher + sauer Moorgewässer. Am Anfang der Entwicklung wächst sie mit einer Fusszelle an verschiedenartigem Substrat befästigt, später aber, im älteren Zustand, findet man sie öfters auch vom Substrat losgelöst und im Wasser herumtreibend. Durch die Ausbildung von akinetenartigen Zellen und verdickten H-Stücke der Membran an den Querwandstellen werden die Fäden nämlich brüchiger und zerfallen leicht in kürzere oder längere Fragmente, die dann fakultativ planktisch auftreten. In ihrer Ar beit über die durch H-Stück-Bau der Membran ausgezeichneten Gattungen

Microspora, Binudearia, Ulotrichopsis und Tribonema, sich auf eine per

sönliche Mitteilung von Beger stützend, identifizierte dann Lucia Wich-

mann(1937) die WiTTROCKSche Art mit der Gloeotila tedorum von Kützing (1849) und introduzierte sie in der Literatur unter dem neuen Kombina tionsnamen als Binudearia tedorum (Kütz.) Beger. Freilich hat Beger,

der also die Identität beider Algen an Hand eines Exsikkates im Herbarium des Bot. Museums Berlin-Dahlem feststellen wollte, selbst darüber nichts veröffentlicht. Die KÜTZiNGSche Alge wurde seinerzeit auf Strohdächern (gesperrt von mir H. S.) bei Jever von Koch eingesammelt. Es scheint nun, dass dieser ausgespochen aérophytischer Standort der KüTziNoschen Alge keineswegs auch für die von Wittrock beschriebene Form charak teristisch sein kann: es ist kaum anzunehmen, dass diese typisch hydro phile, für kühle und ± dystrophe Gewässer bezeichnende Alge ebenfalls als ein so ausgeprägter Aérophyt auftreten könnte. Bis auf weiteres be trachte ich persönlich darum die Frage nach der Identität beider Algen — also der Binudearia tatrana von Wittrock mit Gloeotila tedorum von

Kützing — als nicht endgültig gelöst, sondern einer Nachprüfung bedürf tig. Immerhin kann es sich ja bei der KÜTZiNGSchen Form um eine andere, voraussichtlich typisch aérophile Ulothrichale aus dem engen Verwandt schaftskreis der Gattungen Ulothrix-Hormidium-Binuclearia-Planctonema ect. handeln, da der H-Stückbau der Membran unter gewissen Umständen hier überall in Erscheinung treten kann und für keine der genannten Gat tungen allein charakteristisch ist. Bis also die fragliche KüTziNosche Luft alge wieder einmal gefunden und lebend genauer untersucht sein wird, bevorzuge ich für die ausgesprochenen hydrophile Form der Moorgewässer

die WiTTROCKSche Benennung, weil er die Pflanze unzweideutig veröffent

licht und für sie eine klare, treffende Beschreibung bzw. Charakterisierung gegeben hat, die KÜTZiNGSche Luftalge, also Gloeolila teciorum, dagegen noch viel zu wenig bekannt und geklärt erscheint.

Soweit also was die uns hier interessierende Art und ihre Nomenklatur betrifft. Printz führt allerdings zu ihr (wohl unter dem Kombinations namen von Beger), obschon als besondere Varietäten, zwei weitere Algen an. Eine davon, nämlich die von Skvortzow (1928) aus dem Zaisansee (in Südsibirien) beschriebene Binuclearia zaisanica, besitzt jedoch u. a. etwa dreimal so dicke (bis 36 p) Fäden wie B. talrana, die andere, und zwar

von Tiffany (1937) aus Nordamerika veröffentlichte B. eriensis, hat da

gegen nur 2-3 p breite Fäden. Abgesehen schon davon, dass die Alge

Tiffanys taxonomisch offensichtlich nahe Schmidles Planctonema Lauter-

borni steht, wenn nicht mit dieser identisch ist, wäre eine so grosse Variation

der Fadenbreite (2-36 p) bei ein und derselben Grünalgenart kaum denk bar. Vielmehr handelt es sich hier um 3 selbständige Spezies, wobei die dritte vielleicht sogar zu einer besonderen Gattung (Planctonema) geführt werden kann. Leider fehlt aber letztere in der vorliegenden Übersicht gänz lich und wird auch nicht als Art erwähnt.

Einen anderen besprechungsbedürftigen Fall findet man unter den sog. protopleurokokkoiden Luftalgen Brands(1925), von welchen in dem Buch

von Printznur die Gattung Apatococcus Brandmit zwei Arten, wovon die

eine in einer recht verwickelten Neukombination aufgenommen ist. Man sucht aber vergebens nach dem sehr gemeinen Desmococcus vulgaris Brand

— einer nach allem zu urteilen reduzierten Chaetophorale. Möglicherweise hat sich dabei Printz der Meinung Stockmayers also des Herausgebers der posthumen Arbeit Brands angeschlossen, dass die beiden von Brand unterschiedenen monotypischen Gattungen dieser Gruppe — Desmococcus und Apatococcus — generisch eigentlich nicht zu trennen sind. Freilich ist es hier aber sicher das Umgekehrte der Fall, was auch Geitler (1942/ 1943) bestätigen konnte. Nun hat aber schon Wille, 1913, nach einer ein gehenden Untersuchung des Originalmateriales von Agardh festgestellt, dass die am meisten verbreitete Luftalge — wenigstens in weiten Gebieten Nord- und Mitteleuropas — auf leicht beschatteten Baumstämmen und nicht zu trockenen Felsen der Protococcus viridis von Agardhist. Obschon nicht alle von Agardh als P. viridis bezeichneten Proben diese Alge ent hielten, konnte Willegut und sicher den eigentlichen Träger dieses Namens klarlegen. In der Emendierung von Willeist dann die Gattung Protococcus mit der leicht erkenntlichen Typusart, P. viridis, auch bei Pascher (1915)