The Role of Gender in

Succession Processes

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Management NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonom AUTHOR: Ebba Karlsson and Jonna Persson JÖNKÖPING May 2021

i

Title: The Role of Gender in Succession Processes Authors: Ebba Karlsson & Jonna Persson

Tutor: Karin Hellerstedt Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Family business, Succession, Gender, Gender role theory

Abstract

Background: In family firms, succession is a critical and complex issue and may

determine the business continuity. The succession process often involves a transfer of leadership from one generation to another. Despite acknowledging that gender may affect succession, there is little available research investigating the role of gender in family business succession.

Purpose: This study aims to understand and explore the role of gender in the succession

process and the successor selection. Furthermore, the study aims to contribute to the extant research on gender within the succession process by providing an in-depth study on succession and gender issues in small to medium sized family firms.

Method: This study is guided by a relativist and constructivist research philosophy. The

qualitative study utilises an interview study strategy and is influenced by an inductive approach. Empirical data was gathered through eight in-depth semi-structured interviews with both successors and predecessors. The empirical findings were analysed using a thematic analysis approach.

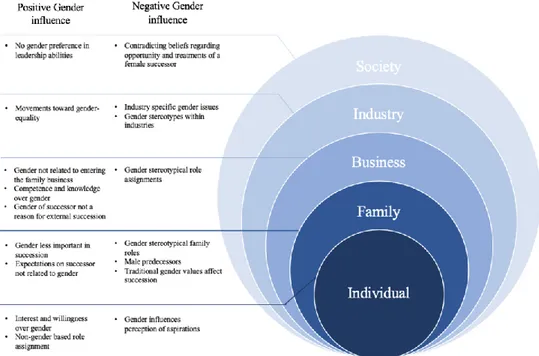

Conclusion: The findings show that gender shapes and influences perceptions and ideas

regarding successors and succession. Thus, gender and gender stereotypes may affect successors assumptions of succession. The study finds that not just predecessors or the family affect perceptions of gender in succession. It is found that gender and gender stereotypes in the society and within the industries may also affect assumptions of succession and successor selection. Despite this, these stereotypes and perceptions do not seem to manifest in the choices or decisions one make regarding successor selection or the succession process in general.

ii

Acknowledgements

We would like to take this opportunity to express our thankfulness towards the people who in different ways encouraged and supported this thesis.

First, a special thank to our tutor Karin Hellerstedt. With deep knowledge, a personal interest and constant support, you have guided us in our process in the most commendable way. Your presence, feedback and thoughts have been tremendously helpful, especially during moments when we, ourselves, felt a little lost. We would also like to express a sincere thank you to our fellow students and friends, who throughout seminars brought us excellent feedback, ideas and comments. To all of you, and to Karin, thank you for the joyful moments.

An equally great thank goes to the interview participants of this thesis. We are grateful for you taking your time to participate in interviews. We sincerely appreciate your valuable insights and experiences, as well as how you were willing to share those with us.

We also want to show our appreciation to those people who openly shared their network, allowing us to get in contact with the interview participants.

These acknowledgements would not be complete without us thanking each other. This experience reassured us that hard work, friendship and teamwork are key aspects for success.

Thank you

Ebba Karlsson and Jonna Persson

iii

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 2 1.3 Research Purpose ... 4 1.4 Research Question ... 4 1.5 Delimitations ... 5 1.6 Definitions ... 5 1.6.1 Family Firm ... 51.6.2 Small and Medium sized Businesses ... 6

1.6.3 Gender ... 6

1.6.4 Successor Selection ... 6

2.

Literature Review... 7

2.1 Family Business ... 7

2.2 The Succession Process in Family Businesses ... 9

2.2.1 Successor Perspective ... 10

2.2.2 Predecessor Perspective ... 12

2.3 Gender Role Theory ... 14

2.3.1 Gender Stereotypes and Choice of Career Path ... 15

2.3.2 Women in Management ... 17

2.4 The Successor Role ... 18

2.5 Successor Development ... 20

2.6 Summary of Literature Review ... 21

3.

Methodology ... 23

3.1 Research Philosophy ... 23

3.2 Research Design ... 24

3.3 Methodological Reasoning of Literature Review... 26

3.4 Data Collection ... 26

3.4.1 Qualitative Interviews ... 27

3.4.2 Selection and Sampling of Participants ... 28

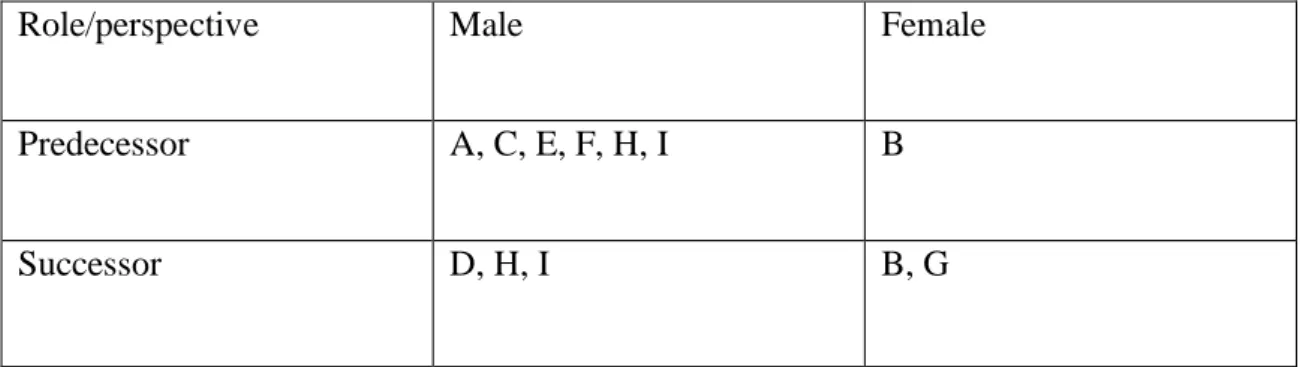

3.4.2.1 Participants Description ... 30

3.5 Quality in Qualitative research ... 33

3.6 Ethical considerations ... 35 3.7 Data Analysis ... 36

4.

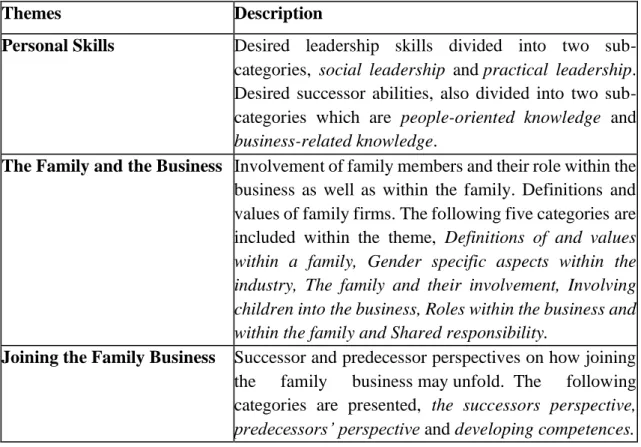

Empirical Findings ... 40

4.1 Themes ... 40 4.2 Personal skills ... 41 4.2.1 Social Leadership... 41 4.2.2 Practical leadership ... 424.2.3 People oriented Knowledge ... 42

4.2.4 Business Oriented Knowledge ... 43

4.3 The family and The Business ... 43

4.3.1 Definitions of and Values Within a Family Firm ... 43

4.3.2 Gender Specific Aspects Within the Industry ... 45

4.3.3 The family and Their involvement... 48

iv

4.3.5 Roles Within the Business and Within the Family... 51

4.3.6 Shared responsibility ... 53

4.4 Joining the Family Business ... 54

4.4.1 The Successors Perspective ... 55

4.4.2 The Predecessors Perspective ... 55

4.4.3 Developing Competences ... 56

4.5 Aspects of Succession ... 57

4.5.1 The Succession Process ... 58

4.5.2 Alternative Succession Outcomes ... 59

4.5.3 Expectations and Understandings ... 59

4.5.4 Gender in Succession ... 60

4.5.5 Succeed with Succession ... 62

5.

Analysis ... 65

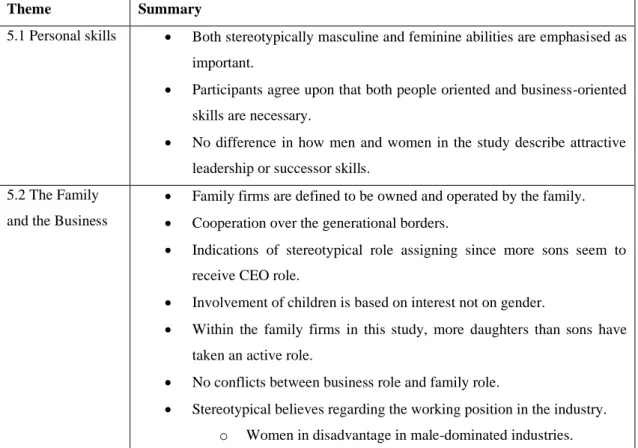

5.1 Personal skills ... 65

5.2 The Family and the Business ... 66

5.3 Joining the Family Business ... 69

5.4 Aspects of Succession ... 70

5.5 Summary of Analysis ... 73

6.

Discussion and Conclusion ... 75

6.1 Conclusion ... 75

6.2 Implications ... 76

6.2.1 Theoretical Implications ... 76

6.2.2 Practical Implications ... 77

6.2.3 Societal Implications ... 78

7.

Limitations and suggestions for future research ... 79

7.1 Limitations ... 79

7.2 Future Research Suggestions ... 79

v

Figures

Figure 1 Coding Scheme... 38-39

Figure 2 Model of the role of gender ... 76

Tables

Table 1 Participant and interview information ... 30Table 2 Overview of participants ... 33

Table 3 Description of themes ... 40-41 Table 4 Summary of Analysis ... 73-74

Appendix

Appendix 1 - Interview question ... 90Appendix 2 - Interview questions ... 91

Appendix 3 - GDPR Consent Form ... 92

Appendix 4 - Themes and Categories ... 93

1

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________ The following chapter introduces the research context through an introduction of family business succession and the role of gender. Furthermore, the research purpose and the derived research question are declared. The chapter concludes with a definition of three particularly important subjects.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

Since the increase of family business research about 30 years ago, researchers have emphasised and studied various aspects of family firms (Bird, Welsch, Astrachan, & Pistrui, 2002; Xi, Kraus, Filser & Kellermanns, 2015). Specifically, the interaction of the two systems in these organisations, the family and the business, have contributed to making family firms such an exciting topic of investigation (Nordqvist, Melin, Waldkirch and Kumeto, 2015; Yu, Lumpkin, Sorenson & Brigham, 2012). Family businesses are not only interesting to investigate, but they are also great contributors to economic growth in various countries throughout the world (Ibrahim, Soufani & Lam., 2001). Moreover, this observation also applies to Sweden since family-owned enterprises account for a large part of Swedish GDP and contribute significantly to the labour market (Andersson, Karlsson & Poldahl, 2017). However, family firms are recognised as having problems ensuring their longevity. It is observed that as little as 30% of all family firms continue into their second generation (Beckhard & Dyer, 1983). Therefore, a critical issue to all family firms is succession, as it can be argued to determine the continuity of the business (Ibrahim et al., 2001). According to research done by Sharma, Chrisman & Chua (2003), succession within the family business context refers to the process of transferring leadership between family members.

After a succession, the change of leader may imply a changed leadership style in both the business and within the family (Hess, 2006). Multiple studies over the last decades have shown that desired leadership qualities and behaviours often are similar to stereotypical male attributes (Fullager, Sumer, Sverke & Slick, 2003; Schein, 2001). The expression

2

“Think manager, think male” relates to the idea that expectations on leadership correlate to masculine traits. It, therefore, becomes natural for a male to be portrayed as a leader (Brands, 2015; Fullager et al., 2003; Schein, 2001). Stereotypical masculine perceptions of a leader include behaviours such as delegating and problem-solving (Prime, Carter & Welbourne, 2009). Commonly, these behaviours are defined as agentic (Barreto, Ryan & Schmitt, 2009). Female behaviour is typically denoted as communal and involves supporting, mentoring, and consulting abilities (Barretto et al., 2009; Prime et al., 2009). However, such qualities that are stereotypically associated with women are not those qualities desired in a successful leader (Fullager et al., 2003; Schein, 2001). Thus, stereotypical assumptions of leadership have contributed to preventing women from entering into top management positions in organisations (Barreto et al., 2009) and resulted in negative perceptions of female leadership (Eagly & Karau, 2002).

Such stereotypes affect the successor role as well. Research shows that the successor position is generally constructed to fit the masculine traits and behaviours, which generate

a rank of the most suitable potential successors. This rank is based on gender due to the

stereotypically aligned masculine traits to the successor role and on the individual´s characteristics that is considered to suit well with the successor role (Byrne, Fattoum & Thébaud, 2019). Appointed female successors generally have higher level of higher human capital than male successors. Even so, this does not affect the rank of possible successors, as the concept of gender is valued higher than the possession of high human capital (Ahrens, Landmann & Woywode, 2015).

1.2 Problem Discussion

As aforementioned, succession is a common subject for discussion in family business research. Authors argue that succession is one of the most critical aspects to consider as it determines the business´s continuity (Ibrahim et al., 2001; Wiklund, Nordqvist, Hellerstedt & Bird, 2013). Thus, much research has been done over the last decades about different aspects of succession in family businesses (Bird et al., 2002). One such aspect frequently being under scrutiny is the comparison between internal and external succession. Arguably, owners of family firms are often faced with the dilemma of either

3

keeping the business within the family or finding a suitable external successor (Thomas, 2002; Wennberg, Wiklund, Hellerstedt & Nordqvist, 2011).

Despite family business research attracting more attention during the last 20 years (Xi et al., 2015), researchers note that family business research lacks a gender perspective (Al-Dajan, Bika, Collins & Swail, 2014). Gender literature states that family business succession can be biased by gender, and daughters are less likely to be potential candidates (Wang, 2010). In their childhood, sons and daughters in family businesses experience different expectations and chances of succeeding their parents due to social gender stereotypes (Kessler Overbeke, Bilimoria & Perelli, 2013). Often, the role of the successor is constructed as stereotypically male (Byrne et al., 2019), and characteristics of successful leaders are often associated with male attributes (Fullager et al., 2003; Shein, 2001). Despite the available research concerning gender and succession in family businesses, surprisingly few studies touch upon why gender still might be a vital aspect of the succession process. Primogeniture, the tradition that the firstborn child will take over the family business (Dyer, 2018), is declining (Kubíček & Machek, 2019). Even so, the preference of a male successor over a female successor is still clearly visible throughout the world (Ahrens et al., 2015). Research has generally tried to understand family businesses supported by agency theory and a resource-based perspective. Although these theories have provided insights into various areas, researchers find that these theories do not address issues such as the role of gender (Kubíček & Machek, 2019). Understandings like this reveal a significant gap in the current literature on family businesses, thus providing an opportunity to apply a gender role perspective on the family business context.

Moreover, Sweden is considered one of the most gender-equal countries in the world. According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2020, Sweden is in fourth place regarding overall gender equality (Word economic forum, 2020). In addition, family businesses are an essential part of the Swedish economy and an essential contributor to society as providers of work opportunities and economic growth (Andersson et al., 2017; Byrne, Fattoum & Thébaud, 2019). However, the majority of research concerning the role of gender and succession in family businesses are conducted in specific geographical areas such as the USA, Canada, Germany and Italy (Ahren et al., 2015; De Massis, Sieger,

4

Chua & Vismara, 2016; Schröder & Schmitt-Rodermund, 2013; Vera & Dean, 2005). All of these countries are placed beneath Sweden in overall equality, according to the Global Gender Gap Report 2020 (World economic forum, 2020). Thus, Sweden emerges as a prominent context for studying the role of gender in family business succession.

Not only is there a visible gap in the literature on gender roles and family business succession. For roles in society not to be dominated by one gender, an understanding of gender equality needs to be implemented. This understanding could lead to opportunities for both men and women to attain and occupy a broader range of social roles. Subsequently, this would diminish the socially constructed stereotypes of what is expected and associated with specific societal norms (Eagly & Wood, 2012). Furthermore, according to Byrne et al. (2019), the preservation of gender inequality in family business succession is an issue that requires urgent attention. The little available research addressing gender issues in family business succession often apply quantitative approaches. However, it is argued that gender issues in family firms have received too little attention to suit such methods (Kubíček & Machek, 2019). This creates a need for research going more in depth to analyse the role of gender in family business succession, thus opening up for qualitative studies.

1.3 Research Purpose

This study aims to understand and explore the role of gender in the succession process and the successor selection. Furthermore, the study aims to contribute to the extant research on gender within the succession process by providing an in-depth study on succession and gender issues in small to medium sized family firms. With this study, the hope is to increase the awareness about gender issues in family firm succession and shed light on an essential and critical issue in many family-owned businesses.

1.4 Research Question

Based on our purpose, we developed the following research question to guide our research:

What is the role gender and gender stereotypes in successor selection and the succession process?

5

1.5 Delimitations

The study aims to have a broad perspective by investigating both successors and predecessor’s perspective of succession. However, to limit the scope some limitations regarding participants have been made. As such, non-successor siblings are not included in the study. Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that their experiences could have contributed to and increased the understanding of succession and successor selection in family firms.

1.6 Definitions

1.6.1 Family Firm

As Leotta, Rizza and Ruggeri (2020) noticed, defining a family business is troublesome. Even though family business research has been considered an independent field of study for more than 20 years, no unified definition of a family business exists (Cano-Rubio, Fuentes-Lombardo & Vallejo-Martos, 2017). Today, how a family business is defined depends on the researcher who defines it, which means that there are several definitions (Astrachan, Klein & Smyrnios, 2002). Some researchers focus their attention on ownership and management (Astraschan et al., 2002). In contrast, others direct their devotion towards generational transfer or family influence (Chrisman, Chua, Pearson & Barnett, 2012). There are even country-specific standards for defining family firms (Klimek, 2016). However, a common starting point for defining family firms – which will also be used in this thesis – is the suggested definition provided by Chua, Chrisman and Sharma (1999). According to Chua et al. (1999):

The family business is a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families (p.25).

6

1.6.2 Small and Medium sized Businesses

Another vital definition to be made concerns the classification of small and medium-sized businesses. Throughout this thesis, the European Commission's definition of a small and medium-sized business will be used. When determining whether an enterprise can be categorised as a small and medium sized, two parameters need to be considered. These parameters are the number of employees and the turnover or balance sheet total. For a company to be considered a small enterprise, the number of staff should be less than 50. The turnover or balance sheet total should be less than or equal to 10 million euro respectively. Moreover, for an enterprise to be considered medium-sized, the staff should be less than 250. The turnover should be less than or equal to 50 million euro, and the balance sheet total should be less than or equal to 43 million euro (European Commission, u.d).

1.6.3 Gender

As the thesis revolves around discussing gender and family business succession, a proper definition of how gender is used throughout the thesis is essential to declare. In family business research, gender is often equated with sex (Byrne et al., 2019) despite the understanding that the two terms correspond to different concepts (Tolland & Evans, 2019). Accordingly, sex is associated with the biological properties of an individual (Tolland & Evans, 2019). In contrast, gender is a social construct concerning behaviours and attributes building on masculinity and femininity (Byrne et al., 2019; Tolland & Evans, 2019). This thesis focuses on the social construct that gender encompasses in relation to the two most frequently discussed sexes, i.e., woman and man.

1.6.4 Successor Selection

The use of selection in the research question may suggest a one-way decision where the successor is left out of any succession decisions. However, throughout the thesis, the word selection denotes the dual aspect of choosing a successor. This duality means that the predecessor must be willing to hand over leadership, and the potential successor must be willing to assume the leadership role (Garcia, Sharma, De Massis, Wright & Scholes, 2019).

7

2. Literature Review

_____________________________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this chapter is to provide the theoretical background to the topic of family businesses, family business succession and gender role theory. Further, role expectations and successor development are discussed. The concluding segment provides the reader

with a general summary of the theoretical background.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Family Business

Family firms account for a large share of existing businesses worldwide (Nordqvist et al., 2015). In Sweden, family firms contribute immensely to the labour market and the general economy, where they answer for a large part of the GDP (Andersson et al., 2017). Despite the importance of family firms to the economy and their long history, research on family firms is a relatively new phenomenon. However, family business research has gained more attention over the last decades (Bird et al., 2002; Pounder, 2015), and is now a well-recognised topic that receives excellent attention (Nordqvist et al., 2015). Nevertheless, before reaching its status as a vital research discipline, family business research had to deal with not being recognised as having its own identity. Instead, it was associated with entrepreneurship and small business disciplines until gaining an independent status (Bird et al., 2002).

When advancing the family business field, researchers started to focus on the unique conditions of family firms (Bird et al., 2002). Thus, researchers began to emphasise factors making family firms different from non-family firms. As a result, it was essential to focus on aspects that family firms share. That meant creating an understanding of family firms as a homogenous group (Chua, Chrisman, Steier & Rau, 2012). However, as research about family firms has progressed, an understanding that family firms constitute a diverse group of entities has emerged. This notion of diversity has caused researchers to argue that family firms are heterogeneous rather than homogeneous (Chua et al., 2012; Chrisman et al., 2012). Researchers have identified several aspects contributing to family firm heterogeneity, such as ownership and family structures. By examining the cause of diversity among family firms, one can enhance the knowledge

8

about their behaviour and performance (Chua et al., 2012; Dyer, 2018). Furthermore, Chua et al. (2012) state that the differences among family firms may be just as many or even more than those existing between family and non-family firms (Chua et al., 2012).

Despite the available arguments favouring family firm heterogeneousness (Chua et al., 2012), the interaction between the family and the business is considered unique for family firms (Tagiuri & Davis, 1996). The intersection between the family and work means that family members will influence the firm simultaneously as the firm will influence the family (Nordqvist et al., 2015). Extending the understanding of a dual interaction in family businesses, some researchers argue for three distinct factors making family firms special. The three factors making family firms unique are family, ownership and management/business and explain the complexity many family firms face (Rutherford, Muse & Oswald, 2006; Tagiuri & Davis, 1996). Tagiuri and Davis (1996) use the term bivalent attributes to explain family, ownership, and management overlap and further state that they are a source for both advantages and disadvantages.

Furthermore, researchers find some aspects more likely to exist in a family firm than in a non-family firm. One such aspect is family-centred-non-economic goals (FCNE) which are different from the more specific goals based on financial and performance expectations (Chrisman et al., 2012). Often associated with the FCNE goals is the concept of socioemotional wealth (Chrisman et al., 2012). This concept incorporates those non-economic goals and focuses on aspects such as the family's identity and capacity to employ family influence (Gómez-Mejía, Takács Hayes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007). For owners of family firms, business success may very well be determined by the amount of socioemotional wealth rather than financial factors. This orientation is very different from that of non-family businesses, where the focus is often on traditional parameters (Dyer, 2018). Even though the FCNE goals are more often visible in family firms, Chrisman et al. (2012) show that implementing such goals is not uniform. Their result corresponds well with what researchers have discussed regarding family firms as a heterogeneous group (Chua et al., 2012).

9

2.2 The Succession Process in Family Businesses

To family firms, succession is considered one of the most critical elements to consider (Ibrahim et al., 2001). Researchers argue that family business succession is a complex process due to the two intertwined roles of leadership and ownership. Many family business entrepreneurs consider the roles of owner and leader to be closely connected. Therefore, leadership succession is often accompanied by an ownership succession (Sund & Ljungström, 2011; Melin et al., 2007). Despite being closely connected, leadership and ownership succession are two different processes. Ownership succession entails selling, giving or sharing stock in the company to the new owners. In contrast, CEO or leadership succession is a process in which there is a transfer of the CEO role from one generation to another (Ramírez-Pasillas & Melin, 2010). According to researchers such as Basco and Calabrò (2017), CEO succession is a highly relevant and essential event since it brings significant changes to an organisation. They further state that CEO succession can be challenging and risky for family firms due to the importance of financial and non-financial goals held by the firm. However, through an effective succession process, family firms may select proper leaders to ensure longevity and revitalisation of the business (Ibrahim et al., 2001).

Predominantly, succession will be initiated due to the leader’s acknowledgement of a need or will to relocate leadership to the next generation (Meier & Thelisson, 2020). The start of such succession could begin immediately after the discussion regarding the incumbent's retirement. Rather than considering the succession as a single event, one should view it as an ongoing and long-spanning process (Ibrahim et al., 2001; Vikström & Westerberg, 2010). Furthermore, the discussion concerning succession generally revolves around three different options. The first alternative to consider is for the incumbent to delay the succession. The second alternative involves entrusting the leadership to a next-generation leader, and the third alternative is to appoint a non-family member as the company leader (Giménz & Novo, 2020). As previously discussed, family firms are often driven by both financial and non-financial goals (Dyer, 2018). Thus, deciding on a successor willing to advance both the financial and non-financial goals are essential. Often, a non-family successor is more likely to focus on the financial aspect and may be more capable of reaching these goals. In contrast, a family member successor perceives the non-financial goals as more intriguing (McMullen & Warnick, 2015).

10

The succession process can be described as an act of transferring knowledge from the incumbent to the successor (Cabrera-Suárez, De Saá-Pérez & García-Almeida, 2001). Further, the process is generally said to involve three broad stages (Cabrera-Suárez, 2005; Ibrahim et al., 2001). The initial stage involves preparing the successor to assume the leadership role. This stage is followed by integration into the business, and the final phase involves the incumbent handing over the leadership to the successor (Ibrahim et al., 2001). Furthermore, Sund and Ljungström (2011) state that a leadership succession often entails obtaining relevant education, training within the family business or gaining experience from other companies to prepare and gather enough knowledge. Additionally, the authors voice the importance of knowing how to handle both family and business-related networks, socialising into the business, and gaining acceptance from stakeholders in the business. However, for succession to even possibly occur, two fundamental criteria need to be met: the incumbent's objective to pass on leadership and the successor´s willingness to undertake the leadership position (Garcia et al., 2019).

2.2.1 Successor Perspective

The potential successor's willingness to assume the CEO role is vital for succession to occur (Venter, Boshoff & Maas, 2005). One factor that has shown to have a contributing effect is the potential successors level of identification with the business. Identification has shown to increase the likelihood that the potential successor views a career in the family business as a viable occupational option (Schröder, Schmitt-Rodermund & Arnaud, 2011). Moreover, commitment to the family business is a factor argued to affect intentions and perceptions towards succession significantly and is expected to mediate engagement in the firm (Garcia et al., 2019; Reay, 2019). Successors commitment towards the family business is likely to be more assertive among those who are provided with the opportunity to engage themselves in changing and adjusting aspects of the business. This feeling results from the successor feeling influential and an appreciated family business member (Reay, 2019).

There are three types of commitment towards the family firm: affective, normative and continuance, all with different origins (Garcia et al., 2019), where affective commitment can be understood as the will to stay within the organisation (Mercurio, 2015). Feelings

11

of obligation towards the organisation relate to normative commitment (Sharma & Irving, 2005). Lastly, continuance commitment correlates to one's concern for costs associated with both work and non-work (Garcia et al., 2019). Moreover, in their study, Garcia et al. (2019) proposed that all three types of commitments would positively affect the successor's engagement. In contrast, other researchers studying commitment found that continuance commitment did not strongly influence a successor's intention towards engaging in the business. However, they found support for both normative and affective commitment influencing the successor (Chan et al., 2020). Further, Schröder and Schmitt-Rodermund (2013) found that the feeling of obligation towards the family did not increase the future heirs' intention to engage in the family business. Instead, they found that driving factors were the perceived possibility of fulfilling career plans and applying knowledge to the firm. On the contrary, research conducted by Dawson, Irving, Sharma, Chirico and Marcus (2014) suggested that a feeling of obligation do not necessarily need to be a negative influence. Additionally, commitment to the family business is found to include gender-related concerns. Despite finding that exposure to the family business is vital to both sons and daughters, sons develop a more significant commitment to the business than daughters (Gimenez-Jimenez, Edelmann, Minola, Calabrò & Cassia., 2020).

Moreover, motivational factors are essential in understanding successors' intentions and perceptions regarding the family firm's succession. Already in their youth, potential successors are often integrated into the family business in various ways. Thus, parents are shown to have an essential and active role in enabling motivation towards succession among adolescents (Schröder & Schmitt-Rodermund, 2013). There are two general types of motivation, autonomous and controlled motivation, each comprising different sublevels. Autonomous motivation originates in one's will and feelings of opportunities. In contrast, controlled motivation derives from feelings of constraints and obligation (Gagné & Deci, 2005). Research finds that both autonomous and controlled motivation are forces pushing adolescents in pursuing careers in the family business. However, most adolescents find autonomous motivation, originating in one's interest to develop a career within the family business, the most affluent (Schröder & Schmitt-Rodermund, 2013). This result is supported by Gagné, Marwick, Brun De Pontet and Wrosch (2019), who found that parents were vital contributors to successors motivation through trusting and empowering the successor.

12

Furthermore, gender may influence how potential successors perceive their possibility of succeeding their parents and pursuing a career within the family business (Kessler Overbeke et al., 2013). Schröder et al. (2011) found that female adolescents raised in a family business were more likely to work outside the family business than succeeding their parents compared to sons. Moreover, in terms of entrepreneurial competence, which is an essential aspect of family businesses, both sons and daughters show equal confidence in their abilities. Nevertheless, succession seems more relevant to sons than daughters (Schröder & Schmitt-Rodermund, 2013).

2.2.2 Predecessor Perspective

As previously noted, commitment and motivation within the successor are essential contributors to their intentions to succeed their parents. The commitment and feeling of motivation are understood to result from parental behaviour (Garcia et al., 2019; Schröder & Schmitt-Rodermund, 2013). Authors consider two different sources of behaviour from parents that influence the potential successor; support and psychological control (Reay, 2019). Parental support involves aspects such as affection and nurturing. On the contrary, psychological control involves more regulatory actions exercised either as sensitive or responsive to oneself or with autonomy to the adolescent (Barber, Stolz, Olsen, Collins & Burchinal, 2005). Researchers find that predecessor behaviour does not directly influence the successors' intentions to either succeed their parents or pursue another career option. Instead, their behaviour has an indirect effect as they contribute to the successors' feelings and motivation concerning the family firm (Garcia et al., 2019). Nonetheless, parental behaviour is crucial as it may increase or decrease the successors' intentions to pursue a career in the firm. By encouragement and support, parents may increase their children's chance of developing an interest in succeeding their parents (Schröder & Schmitt-Rodermund, 2013). However, on the contrary, parental control may negatively influence the potential successors' intention to join the family business (Chan et al., 2020).

Moreover, since succession can be regarded as a process of transferring knowledge, the predecessor must provide an environment that encourages such transfer. At the same time, the environment must provide opportunities for the successor to investigate different managerial approaches (Cabrera-Suarez et al., 2001). Predecessors are encouraged to be

13

flexible in business practices and involve their children in various activities inside the family firm. By this involvement, parents show the potential successors that their contributions to the firm are essential (Reay, 2019). However, research also states that parents should support children in receiving work experience outside the family firm. This experience can increase the successors' belief in themselves and contribute to earning respect and trust from non-family employees (Venter et al., 2005). Thus, incumbents are faced with a dilemma as to not hinder their children from pursuing their career interests while at the same time encouraging them to succeed their parents (Garcia et al., 2019).

To incumbents, succession is an inherently important aspect (Zellweger, 2017). In family firms, the incumbent has a vital role in electing the next CEO. Hence, they have power over whether to elect a family or a non-family member the role of CEO. For incumbents who stress the importance of family standing attributes, intentions to choose a family member increase. However, on the opposite, when managerial experience is seen as the most critical attribute of the successor, incumbents' intentions towards non-family member CEO increases (Basco & Calabrò, 2017). Furthermore, predecessors often attach certain expectations on the potential successor when evaluating their ability as the next CEO (Basco & Calabrò, 2017). According to research done by Schlepphorst and Moog (2014), both so-called hard and soft skills are essential for predecessors when considering prospective candidates. However, these expectations are often not explicit why successors have trouble understanding what is desired of them. Moreover, the authors find that expectations changes during the succession process. For predecessors not yet active in selecting a successor, commitment and motivation are a more frequent topic than those currently engaged in a succession process. During the succession, predecessors consider the relationship between successor and predecessor as increasingly important (Schlepphorst & Moog, 2014).

Furthermore, research concerning family business succession finds that the gender of the potential successor can impact the predecessor's intention and perception of the succession. A study made by Ahrens et al. (2015) tested the predecessors' gender preferences by examining if the likelihood of intra-family succession increased if the predecessor has at least one son. Their result shows that there was a clear preference for sons as successors among the participants in the study. On a similar topic, a study

14

regarding succession in family businesses found that incumbents with a clear focus on appointing a successor with proven managerial competence stress strictly business-related aspects. Thus, the focus shifts from aspects such as gender and birth order towards factors such as financial skills and work experience (Basco & Calabrò, 2017).

2.3 Gender Role Theory

Gender stereotypes can be explained as socially constructed beliefs regarding how men and women are expected to act and behave. Today, beliefs regarding what is considered male versus female behaviour and gender roles appointed by society affect the workplace. Consequently, female entrepreneurs and leaders experience discrimination (Laguía, García-Ael, Wach, Moriano, 2019). Social perceptions and stereotypes of how women and men are expected to act and perform their social role in society can be explained by gender role theory (Eagly & Wood, 2012). In the literature, gender role theory also complies with social role theory (Lanaj & Hollenbeck, 2015).

The idea of role within gender role theory is defined as a bridge between the individual and their social environment. Gender roles can be derived from how frequently they are held by women versus men within the society (Eagly & Wood, 2012). There are two different forms of norms or expectations on roles, namely descriptive and injunctive norms. Descriptive norms are commonly referred to as stereotypes. In other words, expectations on the actual behaviours of individuals belonging to a particular group. Injunctive norms instead describe shared expectations concerning how a specific group of people should behave in a particular situation (Eagly & Karau, 2002). The descriptive observations of individuals' actual behaviour in their roles create beliefs of how the role possessor should act. Gender roles combine both descriptive and injunctive expectations (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Eagly & Wood, 2012).

Role congruity theory is a development of social role theory that goes beyond the social roles. It explores the aspects of a possible congruity between gender roles and other roles seen in the society, particularly leadership roles (Eagly & Karau, 2002). What can be explained by role congruity theory is that due to behavioural expectations, desired attributes in men are often qualities like confidence, assertiveness, and independence. Which all, according to society, are seen to be fitting for a leadership role. The expected

15

attributes of a woman, however, do not align with those of a leader. Instead, society expects a woman to be kind, helpful and nurturing (Eagly & Karau, 2002). Typical male and female behaviour has its roots in the biological differences between the sexes (Wood & Eagly, 2002). For example, in the activities surrounding birth and childcare, a woman benefits from capabilities such as relationship skills and talent in nonverbal communication (Eagly and Steffen, 1984). As a result of this, many occupations are gender segregated. An example of this is how professions such as teachers, nurses and secretaries often are occupied by women (Eagly & Karau, 1991). Another example is the distribution of men and women in top management positions. In Sweden, only 16 % of leaders in top management positions are women (Företagarna, 2017).

Furthermore, the development of gender roles has shown to be a self-regulated process (Eagly & Karau, 2002). Through an internalised process, individuals behave stereotypically because they, on some level, relate to stereotypes associated with their sex (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Eagly & Wood, 2012). Such associations may derive from situational cues, such as a few women in senior positions at the workplace (Eagly & Karau, 2002). This self-regulated process is one explanation for why women are rarely seen in top management positions. Internally, women relate to the traditional female gender role and are therefore less attracted to seeking leadership roles (Eagly & Karau, 2002).

2.3.1 Gender Stereotypes and Choice of Career Path

The stereotypical gender roles discussed in the above section also influence children and their upbringing. Through the actions of family members, teachers and media, they are constantly exposed to gender roles through different environments (Olsson & Martiny, 2018). However, such stereotypical gender roles can be challenged after being placed in scenarios with counterstereotypical role models, that is, individuals occupying non-stereotypical roles. For example, young girls participating in a science camp with female scientists showed less likelihood of picturing a scientist as a man over a woman (Leblebicioglu, Metin, Yardimci, & Cetin, 2011). Even after talking and listening to men and women occupying counterstereotypical occupations, children showed less alignment with traditional gender stereotypes (Tozzo & Golub, 1990). In other words, interaction with role models in a counterstereotypical aspect can reduce gender stereotypes (Olsson

16

& Martiny, 2018). However, a change in beliefs of stereotypes does not necessarily equal a change in the children's behaviour. There is no significant change in young girls' preferences when choosing toys or aspiring for occupations of counterstereotypical character (Olsson & Martiny, 2018). To see the effects of counterstereotypical interactions, there must be a desire in the child to be like the role model, a common ground between the two is necessary (Morgenroth, Ryan, & Peters, 2015). Furthermore, the exposure to counterstereotypical relations needs to be present over a more extended period to show effect (Olsson & Martiny, 2018). One of the effects that can be seen in cases with young girls is that early exposure to a female role model may influence the choice of academic studies (Lockwood, 2006). Thus, showing that even small events that change the children's interest can result in a counterstereotypical career choice in the future (Olsson & Martiny, 2018).

Returning to how impressions of gender roles come from environments everywhere, it is not guaranteed that long-time exposure to counterstereotypical role models will change the child's future ambitions and goals. This is because the role models in different environments may differ in number and visibility (Olsson & Martiny, 2018). For example, if there are more female role models in the household domain than in the occupational domain, expectations of participating within the household domain may be greater than those expectations of engaging within the occupational domain (Olsson & Martiny, 2018). These instances may clash with those insights gained from the counterstereotypical experiences. Therefore, it is crucial to deal with the stereotypes suggesting that women should be the primary representative within the household domain (Olsson & Martiny, 2018).

Furthermore, the scenarios are a bit different when it comes to adolescents. When exposed to role models of a counterstereotypical sort, youths may steer away from aspiring fields in which there is an underrepresentation of their own gender (Olsson & Martiny, 2018). This behaviour can be explained by how they have trouble picturing themselves in the role occupied by the role model; the task seems unreachable (Hoyt & Simon, 2011). This feeling changed when the aspiring adolescents learned that the role model's success was achieved and built on hard work and discipline; an association with the role model was now easier to construct (Hoyt, Burnette & Innella, 2012).

17

2.3.2 Women in Management

The glass ceiling is a common metaphor for describing women absence in top management positions (Manzi & Heilman, 2021). Similar to other theories discussing gender stereotypes, the concept of the glass ceiling describes an invisible barrier for female advancements in the workplace. This barrier is constructed of gender stereotypes that shape female and male behaviour and expectations on their leadership (Barretto et al., 2009). As previously mentioned, women are often associated with being helpful, kind and sympathetic (Eagly & Karau, 2002). Such capabilities are usually described as communal. On the contrary, male behaviour is described as agentic, incorporating assertiveness and individualism (Barreto et al., 2009). Regarding anticipated behaviours in the workplace, Otten and Alewell (2020) tested if the deviation from female and male stereotypes negatively affected one's job satisfaction. Their findings show that women experienced a decrease in job satisfaction if they did not conform to the stereotypical behaviours of females. Men, however, did not experience any adverse effects. An explanation for this could be that men act as norm-setters which permit them to diverge from stereotypical male behaviours with a less negative effect (Otten & Alewell, 2020). Commonly, leaders are described to possess mainly agentic skills. This description tends to result in leaders being recognised as male (Barreto et al., 2009). This is supported by Greenhalgh and Maxwell (2019) as they tested over 8000 essays and images about management and leadership. One aspect that was investigated was the use of the pronouns he and she when describing a leader. They sought to explore if these pronouns were used generically or if one attached a male or female image of a leader to these pronouns. The authors found that leaders were, in most cases, attached to a male image which shows that the average leader is understood to be male (Greenhalgh & Maxwell, 2019).

Similarly, Eagly and Karau (2002) present two forms of prejudice towards female leadership. The first is the less consideration of female than male leadership potential due to leadership stereotypically being seen to consist of male abilities. Second, actual leadership behaviour is perceived to be less desirable in women than men, contributing to female leaders being less approved (Eagly & Karau, 2002). The consequences of these two sorts of prejudices result in negative attitudes towards female leadership. That further leads to difficulty for women to reach and achieve leadership roles and be recognised as

18

effective if successfully doing so (Eagly & Karau, 2002). Also, in the literature regarding family businesses is the concept of the glass ceiling investigated. Songini and Gnan (2009) found the glass ceiling to be present in family firm as women often receive supporting roles instead of governance and managing roles. However, the authors found that family businesses provide an enabling framework for the elimination of the glass ceiling in specific contexts, such as member of board of directors.

2.4 The Successor Role

The interaction of family and business within family firms exists as a possible source of role identity conflicts. Expectations and norms regarding desired behaviour will always be present from both the family and the business. At times these expectations and norms will differ from each other. (Shepherd & Haynie, 2009). Through incongruity in hierarchies in the separate role scenarios, problems such as discomfort, struggles for family members, and tension may arise. A clear example of this is when family members with a low ranked hierarchy position land a higher-ranked position within the business. For other individuals within the family or external parties, knowing which hierarchy to respond to becomes tricky (Barnes, 1988). Female successors within family businesses often acquire the role under special circumstances such as a crisis within the family or lack of willingness or availability of a male descendant (Byrne et al., 2019). To get acknowledgement as the CEO and not be connected to the lower hierarchical level as the daughter in the family, there needs to be a long-term build-up of recognition as a figure of authority and grown-up manner with competence (Barnes, 1988).

The successor role is often constructed to be stereotypically masculine (Byrne et al., 2019). Furthermore, daughters who took over the family business face scepticism and doubt from parents and siblings (Barnes, 1988). Byrne et al. (2019) found that the reasons for the successor role to be of masculine characteristics origins from three different types of mechanisms. The first mechanism is the drawing on a dominant construction of masculinity. Second, by associating the predecessor with an entrepreneurial spirit of a masculine sort. Lastly, by correlating the traits that are being expected in a successor to male individuals. All three mechanisms are exercised through family members collective interactions, communication, cultural norms and beliefs. Combined, such implementations create a close alignment between masculinity, family business and

19

entrepreneurial spirit (Hamilton, 2006). As a result, daughters are not directly or automatically viewed as entrepreneurial or of leadership character, which induce a lower place in the hierarchy of potential successors (Ahrens et al., 2015). This hierarchy is not only based on gender since individual characteristics and personalities who suit the successor role are also important (Byrne et al., 2019).

Cater and Justis (2009) suggest that successors portraying a successive leadership possess six primary abilities. These abilities are a solid and positive relationship with the predecessor, a long-term orientation, a spirit of cooperation, a rapidly and thoroughly gained knowledge regarding the industry and the company, an understanding of the manager role and lastly, an understanding of risk-taking. Furthermore, they state that the findings are based upon the observation that the successors, unlike their predecessors, are not natural entrepreneurs. They enter an ongoing business with challenges originating back to problems they did not set into motion (Cater & Justis, 2009). Another concept regarding desired and expected characteristics in successor CEOs is presented by Cooper and Cardon (2019) in their role residual model. They state that a transition into a new role is influenced both by what the descendant brings into the role and what is left behind by the predecessor. The role residual then explains that what is left behind, such as formal and informal expectations, can affect the successor. Expectations on the role can come from multiple people and can therefore differ. The successor's challenge then becomes to make sense of these expectations together with his or her thoughts regarding what he or she wants to bring to the role. This creates a cycle of returning expectations regarding the role behaviour (Cooper & Cardon, 2019).

Desired characteristics in a successor are portrayed by Humphreys (2013) to be commitment, integrity, and skill towards the business and emotional competence. Such characteristics are often associated with femininity, and supporting, consulting and mentoring are primarily associated with female leadership (Prime et al., 2009). Even if having to work hard to gain recognition and prove competence in successive management, daughters have a chance of being selected as successor, which has increased recently. The oldest son is no longer considered the only choice as a successor (Vera & Dean, 2005). Findings as such propose that family businesses may act as a promising ground for women to be recognised as successive leaders (Byrne et al., 2019).

20

2.5 Successor Development

Preparing successors are crucial for family businesses, and the developmental process involves several important aspects (Sardeshmukh & Corbett, 2011). A fundamental aspect of the development process is the relationship between the successor and predecessor (Cabrera-Suárez, 2005). As previously noted, this relationship impacts the succession process and the successor role (Cater & Justis, 2009; Schlepphorst & Moog, 2014). In their study, Aronoff and Ward (2011) describe seven phases in developing a successor. The two initial steps are attitude preparation and entry, which involves initial partaking in work activities, relationship development and training. Training is an activity that the potential successor can engage in both within the family business and in other organisations. As previously noted, several researchers consider external work experience as highly important to the successor (Sardeshmukh & Corbett, 2011; Sund & Ljungström, 2011; Venter et al., 2005). As Chalus-Sauvannet, Deschamps and Cisneros (2016) note, to successors not trained within the family business, external work experience and the early socialisation process within the business function as a form of training. Moreover, Aronoff and Ward (2011) continue their successor development guide by suggesting that the following steps involve business development, leadership development, selection, transition, and what they describe as the next round. The authors state that these phases include education about the company, development of leadership abilities, the decision regarding who should succeed and the handover of authority from the predecessor to the successor. Lastly, the next round relates to the understanding that succession in family firms is a cyclical process that will start over once the current succession is finalised (Aronoff & Ward, 2011).

Furthermore, to install and develop potential successors to assume the leadership role, socialisation has a substantial contributing effect (García-Àlvarez, López-Sintas & Gonzalvo, 2002). The process of socialisation involves two separate phases, both important to the individual. Primary socialisation is the initial phase and begins already in childhood. During this stage, the child is initiated into the norms, values and manners exhilarated by their environment. The subsequent phase is described as secondary socialisation involving a development of role-specific knowledge (Berger & Luckmann, 1991). In their study, Garcia-Àlvarez et al. (2002) developed two structures for socialisation based on the understandings of primary and secondary socialisation.

21

However, their designs are developed principally for the family business context and involve a phase of family socialisation and a business socialisation phase. Their findings pointed to family socialisation as a process where the predecessor instils values within the successor. In contrast, business socialisation involves the successor's entry into the business and predecessor-successor relationship. Similarly, Cabrera-Suárez (2005) addresses CEO succession as a process including socialisation in which the successor is educated in norms and role systems of the family firm. Moreover, in family firms where the successor is a non-family member, socialisation is argued to also serve as an essential factor. Through the socialisation process, mutual understandings and role acquiring are more easily developed and may ease the succession (Hall & Nordqvist, 2008). Similarly to what is said regarding the successor development process, socialisation requires and is dependent on the relationship between the successor and the predecessor (Cabrera-Suárez, 2005).

2.6 Summary of Literature Review

This part summarises the literature review to provide the reader with essential concepts and ideas. Note also that this section is derived based on our interpretations and understandings of the literature presented in the sections above.

The Family business presents itself as a two-systems entity structured on the family and the business, which presents exciting research opportunities. Research on family businesses underlines the importance of succession as it is a prerequisite for family business continuity. Much of the literature concerning family firms have approached succession from a predecessor perspective. However, the literature review also reflects the increasing volume of research, with emphasis on successors. The literature review reflects the different conditions that family business succession consists of and discuss that motivation and commitment on the part of the successor is an essential aspect to consider in succession. However, predecessors’ intentions and perceptions show to have a great influence as they often elect successors. Although some research on succession in family businesses not explicitly focusing on the role of gender in succession, it is clear that gender and gender stereotypes influence succession. As succession in family businesses involves a transfer of leadership, it becomes interesting to explore gender roles and gender stereotypes. Gender role theory describes gendered assumptions and

22

expectations of the society and its influence on aspects such as leadership and perceptions of leaders. Research on successor roles stresses that the two systems in the family firm, the family and the business, represent a source of role conflicts. As family firms are built on and structured around certain norms, this will have implications for all individuals present within the family and the business.

23

3. Methodology

_____________________________________________________________________________________ The chapter begins with a discussion regarding the applied research philosophy and the derived research design Thereafter, the methods for data collection, interview design, sampling strategy and participant description are presented. The chapter continues with the method for data analysis and finishes with discussions regarding research quality and ethics.

_____________________________________________________________________

3.1 Research Philosophy

Research philosophy is an essential factor in the research. It provides the authors with critical understandings of underlying factors that may significantly impact the outcome of the research. With a clear recognition of the underlying philosophical assumptions, the researcher can have a reflexive stance and determine how to design and improve the research (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson and Jaspersen, 2018). For most instances, philosophers' crucial concern is ontology and epistemology, constituting the two main dimensions of research philosophy (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Ontology can be understood as the core of research philosophy and embodies the fundamental assumptions that one construct about the nature of reality (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). We found applying a relativist ontology to correspond with the nature of this study and our perception of reality. This choice is based on the fact that relativism acknowledges that experiences, knowledge and views of different individuals may differ, considering that multiple perspectives exist. (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Furthermore, as gender role theory is based on certain assumptions, the relativist stance is considered suitable. With a relativist worldview, one expects a phenomenon to depend on the angles by which it is observed and further acknowledge that different observers may have distinctive views that point to multiple truths (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). The application of relativism can also be understood from our interest in utilising a great diversity of family firms and their representatives. This enlightened our belief that different individuals would have different perceptions and experiences of successions in family businesses.

24

Following ontology is the epistemology that may be understood as a theory for constructing knowledge based on the researcher’s worldview (Saldaña, Leavy & Beretvas, 2011). Epistemology has formed the centre for a debate among social scientists. Two different positions are said to make up the epistemology: positivism and social constructionism (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). The epistemological position corresponding well with our relativist worldview is social constructivism. It, similarly to relativism, assumes reality to be determined by people and focuses on individuals' experiences (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Furthermore, social constructivism is well suited to our interest in different individuals' experiences and understandings (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Thus, we saw the relevance of using social constructionism throughout our research. As researchers, we sought to acknowledge our presence. Together with the family firm representatives, we would create an understanding of the social reality (Berger & Luckman, 1991; Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

3.2 Research Design

Qualitative research studies the concepts of different socially constructed realities. Perspectives from different participants in their everyday activities and knowledge are captured in the text as the empirical material (Flick, 2008). Due to the characteristics of the intended issue under examination, a qualitative approach is considered the most appropriate. A qualitative study identifies a gap in existing literature, which in our case was the lack of research on succession with the perspectives of gender role theory. Hereafter, the aim was to create a suitable research question on the topic. This in order to be able to conclude findings through collection and analysis of data that may contribute to increased knowledge (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

Qualitative researchers involve themselves in the study by interpreting the surroundings in the way society brings meaning to it. This involvement is done through taking field notes, conducting conversations and interviews, writing down memos and using photographs and recordings (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005). We decided to conduct an interview study since we found it to suit our research purpose. In addition, since case

25

studies are considered suitable for qualitative research (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018), we took inspiration from the case study method and applied certain features to our interview study. Case studies value deep understanding, especially in providing new concepts and ideas and validating their importance (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Furthermore, case studies seek to understand "how" or "why" a social phenomenon acts and works (Yin, 2018).

Utilising an interview study allowed us to gather a significant amount of data from multiple participants by asking the same or similar questions. That data was analysed in an in-depth manner to generate a list of common and similar issues (Vogt, Gardner, & Haeffele, 2012), similar to the method of a multiple case study (Yin, 2018). As the paper intended to investigate the role of gender in succession processes, the method of choice was relevant for the research topic. The method endorsed regular contact with interviewees for ensured accuracy (Bluhm, Harman, Lee & Mitchell, 2011), which was practical and of good use in our study. Considering that there are some negative aspects regarding multiple case studies, we have tried not to incorporate such aspects into our interview study. For example, the researcher may not have the necessary skills and may let uncertain results influence the direction of the findings and conclusions (Yin, 2018). Furthermore, by following the desired attributes in a researcher described by Yin (2018), we, as researchers, have avoided such problems to the best of our ability. Through a holistic understanding of the issues under study, the right asked questions, the intention to be good listeners, and the study's ethical responsibility, we ensured high quality in the study (Yin, 2018).

Since this thesis is concerned with the experiences and understandings of specific individuals in specific family businesses, the results from this study may or may not be applicable to other contexts. Therefore, we decided to take inspiration from the expressive case study strategy, and apply to our interview study (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Because of the specific interest in the role of gender in succession within family firms, the perspective of choice is considered suitable. Furthermore, the conducted interview study took inspiration from the exploratory/ descriptive interview approach with the intention to study and learn as much as needed from the participants´ experiences (Vogt et al., 2012).

26

When analysing data and drawing conclusions, there are three main research modes: deduction, induction, and abduction. In this study, we took inspiration from the inductive approach. Being influenced by the inductive approach allowed us to analyse our findings and interpret them with the knowledge that they are a reality constructed by both the interviewees and us as researchers (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). To ensure high quality and confidence in the results, we utilised some triangulation methods (Yin, 2018). In our case, interview transcripts and observations, as an addition to the conducted literature review, ensured a more accurate understanding of the elements as a whole within the data (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

3.3 Methodological Reasoning of Literature Review

Critical to any research is the literature review as it lay the foundation for the study and help the researcher build cohesiveness (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2007). To increase our knowledge regarding family business succession and the role of gender, we began the research process by conducting a thorough search for literature and build the literature review. Through the literature search and by analysing previous research, we were able to identify the research gap, thus enabling us to articulate the purpose of this thesis.

We approached the search for literature by defining a number of keywords that we saw would suit the intended research aim. Such keywords included family business, succession, gender, successor, predecessor and gender roles. As we reviewed the articles found using the defined keywords, we also took notice of prominent studies used in the reviewed articles. By approaching the search for literature from this angle, we were able to detect studies that we were not able to capture within the keywords used in the initial search that was still highly useful. As such, we reviewed and analysed numerous studies that we could use when building a solid foundation for the thesis.

3.4 Data Collection

Qualitative studies are often more exploratory, and the methods for collecting data often revolve around the use of language and text. Qualitative research can be understood as a creative process where one tries to comprehend the respondents’ sense-making of their nature of reality (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). Qualitative data consist of information